Abstract

Background/Aims:

Mobility disability and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) are common in aging and both are associated with risk of death. This study tested the hypothesis that risk of death differs by the order in which mobility disability and MCI occurred.

Methods:

1,262 community-dwelling older adults were unimpaired at baseline and followed annually. Mobility disability was based on measured gait speed and MCI was based on cognitive performance tests. A multi-state Cox model simultaneously examined incidences of mobility disability and MCI to determine whether the order of their occurrence is differentially associated with risk of death.

Results:

The average age was 75.3 years and 70% were female. While mobility disability occurred more frequently than incident MCI, the subsequent risk of death was higher in participants who developed MCI alone compared to those who developed mobility disability alone (hazard ratio=1.70, P=0.018). Of the participants who initially developed mobility disability, about half subsequently developed MCI which doubled their risk of death (hazard ratio=2.17, P<0.001). By contrast, over two thirds who developed MCI subsequently developed mobility disability which did not further increase their risk of death.

Conclusion:

Mobility disability occurs more frequently in community-dwelling older adults, but MCI is more strongly associated with mortality.

Keywords: mobility disability, cognitive impairment, mortality

Introduction

As adults age, many will develop mobility disability, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or both. Individuals with motor or MCI are at an increased risk of death (1, 2) and the effects on mortality are likely synergistic (3). Despite the wealth of prior work, the frequency and temporal relationship of incident mobility disability and MCI, as well as the extent to which the order of their occurrence may differentially affect an individual’s subsequent risk of death have not been investigated. Notably, mobility disability predicts cognitive decline and incident dementia (4–6), and poor cognition also predicts decline in gait speed and incident mobility disability (7–9). Disentangling these complex interrelated processes requires an analytic approach that models both incident events simultaneously while taking into account the competing risk of death.

To fill this knowledge gap, we employed a multi-state Cox model using data from 1,262 older adults participating in one of two community-based cohort studies of chronic conditions of aging. All participants were free of mobility disability or MCI at baseline and followed annually for up to 24 years. First, we estimated the rates of transitions from no impairment to either mobility disability or MCI, as well as the rates of subsequent transitions from mobility disability to MCI and from MCI to mobility disability. Next, we compared the risk of death between participants who had no impairment, those who developed either incident mobility disability or incident MCI alone, and those who developed both impairments (MCI after mobility disability and separately mobility disability after MCI).

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were community based older persons from one of two ongoing cohort studies of aging, the Religious Orders Study and the Rush Memory and Aging Project (ROSMAP) (10). Participants were followed annually for clinical and cognitive evaluations. The two studies share a common core of testing battery which facilitates combined analyses.

To examine whether the order of incident impairments affects the risk of death, these analyses were restricted to 1,262 ROSMAP participants without mobility disability or cognitive impairment at baseline and had at least 1 follow-up visit. The mean baseline age was 75.3 years (standard deviation [SD]: 7.0), 884 (70%) were female, the mean years of education was 16.7 (SD: 3.6), and most were non-Latino white (N=1162, 92%).

Mobility disability

To circumvent self-reported recall bias, mobility disability was based on annual measured gait speed. Time to walk 8 feet (2.4m) at usual pace was recorded using a stopwatch. Incident mobility disability was determined at the first visit at which the gait speed was below 0.55 m/s. The cut-point of 0.55 m/s was previously established in this cohort by comparing sensitivity and specificity of gait speed in predicting self-report mobility disability in non-demented participants using the Rosow-Breslau scale at study entry (11, 12). Similar cut-offs (e.g. 0.5m/s) have been implemented by other studies (13).

Mild cognitive impairment

Uniform structured clinical assessments were administered at baseline and annual follow- up visits, as previously described (14, 15). The assessment includes a battery of 21 cognitive performance tests, a medical history interview, and an in-person neurological examination. Clinical diagnoses of cognitive impairment and dementia follow a three step process. First, the cognitive tests were scored by computer and the participant was assigned an education-adjusted cognitive impairment rating. Second, the impairment ratings and cognitive tests scores, together with records on education, occupation and sensorimotor function were reviewed by a board certified neuropsychologist to determine the presence of cognitive impairment. Third, all available records were reviewed by a clinician and a decision on the presence of dementia and its most likely etiology was rendered. Clinical diagnosis of dementia follows the recommendations of the National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (16), which requires a history of cognitive decline and impairment in at least 2 cognitive domains. Notably, the dementia diagnosis is not restricted to Alzheimer’s disease. A diagnosis of MCI was rendered if the participant was judged cognitively impaired by the neuropsychologist but did not meet dementia criteria by the clinician. For the purpose of present analyses, incident MCI was determined at the visit when a participant was first diagnosed with either MCI or dementia.

Medical risk factors and conditions

Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Histories of smoking and hypertension were reported by the participants during the interview. Diabetes was based on self-report and medication history. Claudication and heart condition were self-report. Stroke diagnosis was rendered by the clinician through interview and review of neurological examination and cognitive testing. Urinary incontinence is present if participants report any occurrence of incontinence during the month prior to the interview. Selfreported joint pain refers to pain in axial, lower or upper extremities on most days that last at least a month.

Statistical analysis

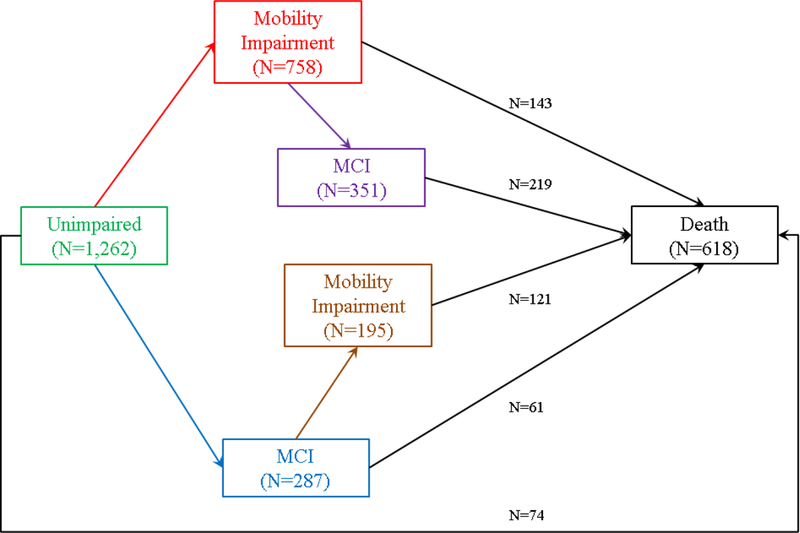

The event rate was summarized using the number of events per 1000 person-year at risk, censoring at the competing events. To model incident mobility disability, incident MCI and death, we hypothesized a multi-state transition structure which consisted of six states including: (1) an initial state of no impairment, four intermediate states of (2) incident mobility disability without incident MCI (MD), (3) incident MCI without incident mobility disability (MCI), (4) incident MCI after incident mobility disability (MCI|MD), and (5) incident mobility disability after incident MCI (MD|MCI), and finally (6) an absorbing state of death (Figure 1). As death could occur without any impairment, with either impairment or with both impairments but in different temporal order, the model structure includes a total of 9 distinct transitions as follows.

Figure 1.

describes a multi-state transition model for incident mobility disability, incident MCI and death. This model includes six states: no impairment, mobility disability alone, MCI alone, MCI after mobility disability, mobility disability after MCI, and death. Each arrow represents one of the 9 distinct transitions. The black arrows represent the 5 transitions that lead to death.

We fit a multi-state Cox model to estimate the hazards of these events in a single framework (17). Briefly, individual hazard from state i to state j, denoted by λij(t|Z), is specified as follows,

Here, λij,0(t) is the baseline hazard, Z is the covariates vector and the corresponding β quantifies its association with the hazard. The model included terms for baseline age, sex and years of education and allowed their associations to differ for each of the individual transitions.

To test the difference in risk of death by the order of incident mobility disability and incident MCI, we simplified the model by assuming proportional hazards for the 5 transitions that lead to death,

The indicators δk, where k = i – 1, tested the difference in risk of death between the competing transitions. The proportional assumption was checked by using Schoenfeld residuals against the transformed time (18) and no evidence of non-proportionality was found.

The analyses were performed using SAS/STAT software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and the mstate package for R (19). Statistical significance was determined using a nominal α level of 0.05.

Results

Incident mobility disability and incident MCI

All 1,262 participants included in this study were free of mobility disability or cognitive impairment at baseline. The median baseline Mini Mental Status Examination score was 29 (Interquartile range [IQR]=28 to 30) and the mean baseline gait speed was 0.77 m/s (SD=0.16). Over an average of 10 years of follow-up (Range: 1–24), 758 (60.1%) unimpaired participants developed mobility disability (Incidence rate=133.7 per 1,000 person-years, 95% CI: 124.4–143.6). By contrast, incident MCI was much less frequent, where 287 (22.7%) unimpaired participants developed MCI (Incidence rate=50.6 per 1,000 person-years, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 44.9–56.8).

Compared to older adults with no impairment, incident MCI occurred more frequently in those who first developed mobility disability. Of 758 participants who first developed mobility disability, 351 (46.3%) subsequently developed MCI (Incidence rate=84.0 per 1,000 person-years, 95% CI: 75.4–93.3). Similarly, the incidence rate for mobility disability was higher for participants who first developed MCI compared to unimpaired individuals. Of 287 participants who first developed MCI, 195 (67.9%) subsequently developed mobility disability (Incidence rate=176.7 per 1,000 person-years, 95% CI: 152.8–203.3). We examined the baseline risk factors and medical conditions, including BMI, vascular risk factors, vascular diseases, joints pain and urinary incontinence. We did not observe significant between-group differences in these conditions except that a larger proportion of individuals who developed mobility disability reported joint pain at baseline (Table 1).

Table 1.

Group difference in health factors at baseline

| Unimpaired N=217 |

MD N=407 |

MCI N=92 |

MCI|MD N=351 |

MD|MCI N=195 |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI1 | 26.3 (23.3–30.1) | 27.0 (23.9–31.6) | 26.0 (23.6–29.2) | 26.1 (23.9–29.1) | 26.4 (24.0–29.2) | 0.060 |

| Smoking2 | 76 (35.0%) | 132 (32.4%) | 31 (33.7%) | 70 (35.9%) | 99 (28.2%) | 0.324 |

| Hypertension2 | 106 (48.9%) | 187 (46.0%) | 39 (42.4%) | 88 (45.1%) | 151 (43.0%) | 0.695 |

| Diabetes2 | 23 (10.6%) | 48 (11.8%) | 14 (15.2%) | 15 (7.7%) | 26 (7.4%) | 0.088 |

| Claudication2 | 8 (3.7%) | 13 (3.2%) | 2 (2.2%) | 14 (7.2%) | 22 (6.3%) | 0.075 |

| Stroke2 | 9 (4.7%) | 21 (5.8%) | 3 (3.4%) | 7 (3.7%) | 22 (6.6%) | 0.564 |

| Heart conditions2 | 13 (6.0%) | 32 (7.9%) | 10 (10.9%) | 18 (9.2%) | 35 (10.0%) | 0.441 |

| Joints pain2 | 82 (37.8%) | 175 (43.0%) | 20 (21.7%) | 69 (35.4%) | 140 (39.9%) | 0.004 |

| Urinary incontinence2 | 93 (42.9%) | 195 (48.0%) | 33 (35.9%) | 80 (41.0%) | 166 (47.3%) | 0.136 |

MD: incident mobility disability without developing MCI, MCI: incident MCI without developing mobility disability, MCI|M after incident mobility disability, MD|MCI: incident mobility disability after incident MCI.

Median (Q1-Q3) and the comparison was done using KS test;

N (%) present and the comparison was done using Chi-squared test.

Incident mobility disability, incident MCI and death

First, we described the death rates among individuals without impairment, with either incident mobility disability or incident MCI alone, and with both incident mobility disability and incident MCI but in different temporal order. Of 1,262 participants who were unimpaired at baseline, less than 6% (N=74) died without developing mobility disability or MCI (Death rate=13.1 per 1,000 person-years, 95% CI: 10.3–16.4). About 19% (N=143/758) of participants who developed mobility disability died without subsequent incident MCI (Death rate=34.2 per 1,000 person-years, 95% CI: 28.8–40.3). About 21% (N=6½87) of participants who developed MCI died without subsequent incident mobility disability (Death rate=55.3 per 1,000 person-years, 95% CI: 42.3–71.0). Notably, the death rates for the participants who had both impairments are higher. The death rate for participants with incident MCI after incident mobility disability was 130.6 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI: 113.8–149.1), and the death rate for participants with incident mobility disability after incident MCI was 104.2 per 1,000 person-years, (95% CI: 86.4124.5).

To test the difference in risk of death between participants with and without different combinations of impairment, as illustrated by black arrows in Figure 1, we employed a multi-state Cox model, adjusted for age, sex and education. Relative to unimpaired participants, we did not observe a difference in the risk of death for those who developed only mobility disability (P=0.55). By contrast, those who developed only MCI had a nearly 2-fold increase in risk of death as compared to the unimpaired (Hazard ratio [HR]=1.92, 95% CI: 1.16–3.17, P =0.011) or participants who developed only mobility disability (HR=1.70, 95% CI: 1.10–2.63, P =0.018).

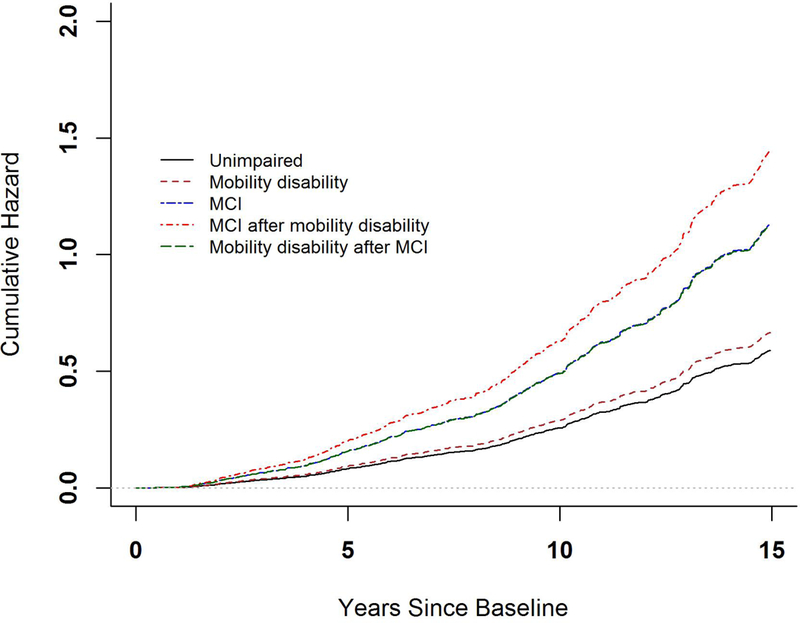

Compared with unimpaired participants, those who developed both impairments had greater risks of death. The hazard ratios were 2.45 (95% CI: 1.64–3.65, P<0.001) and 1.91 (95% CI:1.23–2.97, P =0.004) respectively for participants who developed MCI after incident mobility disability and those who developed mobility disability after incident MCI. Notably, individuals who developed MCI after mobility disability had an increased risk of death compared to participants who developed only incident mobility disability (HR= 2.17, 95% CI: 1.65–2.86, P <0.001). By contrast, participants who developed mobility disability after MCI did not show a further increase in their risk of death compared to participants with incident MCI alone (P =0.99). Further, for participants with both mobility disability and MCI, their subsequent risk of death did not differ by the order in which the impairments occurred (P=0.11). Figure 2 summarizes these analyses by illustrating the cumulative hazards of death for participants with different combinations of incident mobility disability and incident MCI prior to death.

Figure 2.

illustrates the difference in risk of death by order of incident mobility disability and incident MCI. Each curve represents cumulative hazard of death for individuals who had no impairment (black), incident mobility disability alone (brown), incident MCI alone (blue), incident MCI after mobility disability (red) and incident mobility disability after MCI (green). Note that the green and blue curves are superimposed on one another. These cumulative hazards were estimated from a multistate proportional hazards model.

To assess that our results are robust against choice of the cut-off for mobility disability, we repeated the analyses using an alternative cut-off of 0.8 m/s. A total of 480 participants without mobility disability were eligible for the analysis, and the results were similar to the cut-off of 0.55 m/s employed in our primary analyses. Incident mobility disability was more frequent than incident MCI such that 88.1% (N=423) of the unimpaired participants developed mobility disability while only 5.8% (N=28) developed MCI. Incident MCI occurred more frequently among participants who developed mobility disability than the unimpaired. Of the participants who first developed mobility disability, 200 (47.3%) subsequently developed MCI. We did not observe a difference in the risk of death between the unimpaired and those who developed only mobility disability (P=0.07). By contrast, the risk of death was higher for participants who developed MCI, regardless of whether they had MCI only or had both MCI and mobility disability (all Ps <0.05).

Next, we examined whether decline in gait speed differed between individuals who had incident mobility disability only (N=407), those who developed mobility disability before incident MCI (N=351) and those who developed mobility after incident MCI (N=195). We fit a linear mixed model with annual gait speed measure as the continuous longitudinal outcome. In this model, the groups (degrees of freedom=2), time in years since baseline and the interaction between the two were the main predictors. After the adjustment for age, sex and education, for individuals who developed mobility disability only, the estimated rate of decline in gait speed was 0.30 m/s per decade (standard error (SE)=0.01, P<0.001). The decline was similar for those who later developed MCI (additional rate of decline=0.002 m/s per decade, SE=0.011, P=0.840). By contrast, individuals who first developed MCI and subsequently mobility disability had faster decline (additional rate of decline=−0.038 m/s per decade, SE=0.014, P=0.006).

MCI is a prodromal stage of dementia for many adults. For individuals who developed MCI, we compared the odds of death with and without subsequent dementia. The comparisons were done for the three groups: individuals with incident MCI only, individuals who had incident MCI and later developed mobility disability, and individuals who had incident MCI after they had first developed mobility disability. Of the 92 individuals who had incident MCI but no incident mobility disability, 22 developed dementia and all (100%) died. By contrast 55.7% of the nondemented died (P<0.001). There were 195 individuals who had incident MCI and subsequently developed mobility disability. Of those, 89 had dementia and 62 (69.7%) died; 106 were nondemented and 59 (55.7%) died (P=0.045). Of the 351 individuals who had incident MCIs after developed mobility disability, 158 later had dementia and 112 (70.9%) died; 193 were nondemented and 107 (55.4) died (P=0.003). These results suggest that dementia plays an important role on the risk of death.

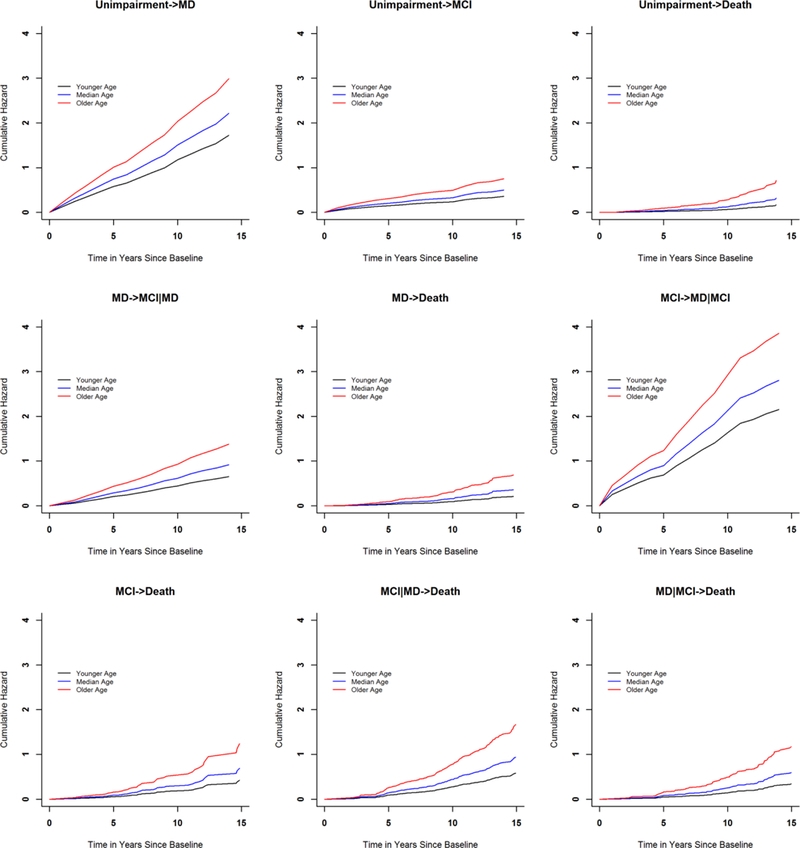

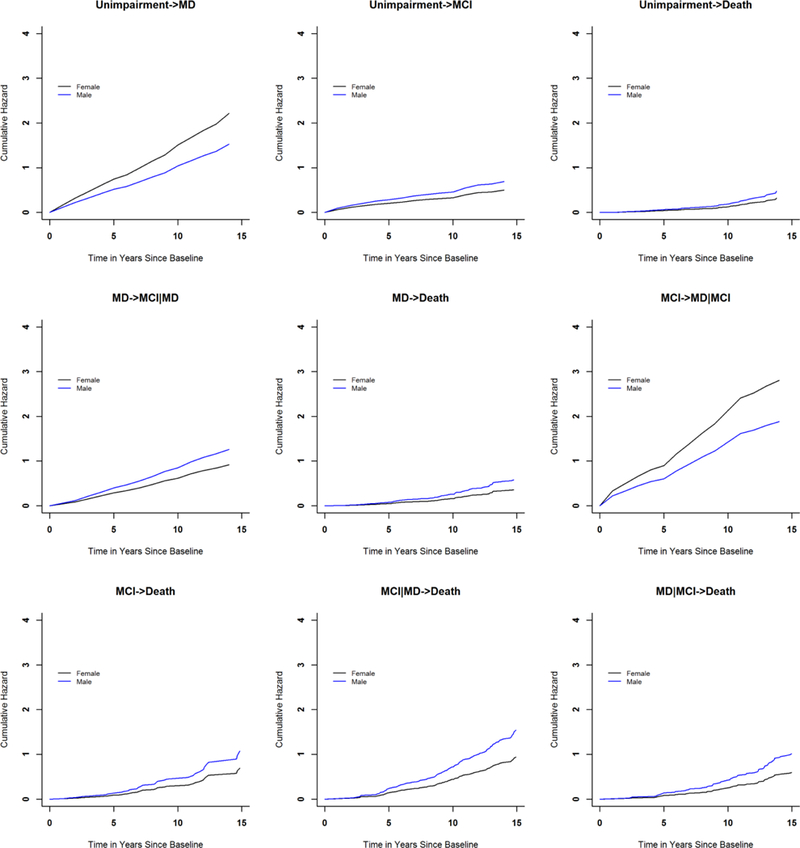

Associations of demographics with incident impairments and death

We examined the associations of age, sex and education with risk of each of the nine individual transitions (e-Figures 1 and 2). Older age at baseline was associated with greater risks of incident mobility disability, incident MCI and death (all Ps<0.001) (Table 2). Males had a lower risk of incident mobility disability, regardless whether participants previously had incident MCI (HR=0.72, P=0.038) or not (HR=0.71, P<0.001). Separately, Males had a greater risk of incident MCI, regardless of whether participants previously had incident mobility disability (HR=1.32, P=0.038) or not (HR=1.34, P=0.019). Males also had a greater risk of death, particularly among participants who had developed mobility disability. The hazard ratio was 1.59 (p=0.011) for those with incident mobility disability alone; 1.65 (p<0.001) for those with incident mobility disability and subsequently incident MCI; and 1.63 (p=0.010) for those with incident mobility disability after incident MCI (Table 3). Education was not associated with either incident impairment or death (all ps>0.05, results not shown).

Table 2.

Associations of Baseline Age with Incident Impairment and Death

| MD | MCI | MCI|MD | MD|MCI | Death | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Impairment | 1.05 (1.04–1.06), <0.001 | 1.07 (1.05–1.09), <0.001 | NA | NA | 1.14 (1.10–1.18), <0.001 |

| MD | NA | NA | 1.07 (1.05–1.09), <0.001 | NA | 1.12 (1.09–1.15), <0.001 |

| MCI | NA | NA | NA | 1.05 (1.03–1.08), <0.001 | 1.10 (1.06, 1.14), <0.001 |

| MCI|MD | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.11 (1.09, 1.14), <0.001 |

| MD|MCI | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.11 (1.08–1.15), <0.001 |

MD: incident mobility disability without developing MCI, MCI: incident MCI without developing mobility disability, MCI|MD: incident MCI after incident mobility disability, MD|MCI: incident mobility disability after incident MCI. NA: Not applicable.

Numbers in each cell represent hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) and P values.

Table 3.

Associations of Male Sex with Incident Impairment and Death

| MD | MCI | MCI|MD | MD|MCI | Death | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Impairment | 0.71 (0.30–0.84), <0.001 | 1.34 (1.05–1.70), 0.019 | NA | NA | 1.50 (0.95–2.39), 0.083 |

| MD | NA | NA | 1.32 (1.04–1.67), 0.022 | NA | 1.59 (1.11–2.27), 0.011 |

| MCI | NA | NA | NA | 0.72 (0.53–0.98), 0.038 | 1.56 (0.93–2.60), 0.089 |

| MCI|MD | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.65 (1.24–2.22), <0.001 |

| MD|MCI | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.63 (1.12–2.38), 0.010 |

MD: incident mobility disability without developing MCI, MCI: incident MCI without developing mobility disability, MCI|MD: incident MCI after incident mobility disability, MD|MCI: incident mobility disability after incident MCI. NA: Not applicable.

Numbers in each cell represent hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) and P values.

Discussion

While incident mobility disability and MCI are interrelated and common in aging, there is much heterogeneity among older adults in both incidence rate and the order in which they occur. Using data from more than 1250 unimpaired older adults, the analytic approach employed in this study modeled both incident mobility disability and MCI simultaneously while taking into account their competing risk of death. This approach allowed us to fill an important knowledge gap and determine if the order of their occurrence is differentially associated with risk of death.

This study confirms the impact of cognitive impairment on mortality, but the lack of an association of mobility disability alone with increased risk of death challenges prior reports that slower gait speed increases mortality (20–23). While our current findings need to be replicated, they underscore the importance of considering cognitive impairment when assessing the effect of mobility disability on risk of death. It is unclear to what extent prior reports about the association of gait speed with mortality can be explained by cognitive impairment which seems to be the main driver of mortality in the current analyses. If our findings are confirmed, since older adults with mobility disability are more susceptible to mild cognitive impairment, interventions to prevent mobility disability may also require concomitant strategies to prevent the development of cognitive impairment to optimize their survival.

By estimating the incidence rates of mobility disability and MCI in the presence of the competing risk of death, our data show that each impairment may occur in the absence of the other, but incident mobility disability is more frequent than incident MCI. Furthermore, our results suggest that incident mobility disability and incident MCI are linked to each other, such that, compared to the unimpaired, the risk of developing a second impairment was higher in participants who had previously developed either impairment. This progression from no impairment to a single impairment and then multiple impairments is consistent with our prior work which suggests that both cognition and mobility may share a common underlying pathophysiology (24, 25). Prior evidence suggests that the Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele, the most potent genetic risk factor for late onset Alzheimer’s disease, is also associated with faster motor decline. Neurofibrillary tangles in substantia nigra are implicated in gait impairment.

Importantly, mobility disability and cognitive impairment may also share an underlying vascular footprint. Periventricular white matter hyperintensities are associated with decline in gait as well as memory performance (26, 27). White matter lesions and lacunes are common in older adults with lower extremity Parkinsonism which is accompanied by urinary incontinence and cognitive impairment. We previously showed that macroscopic infarcts are associated with simultaneous decline in frailty and cognition (28). Identifying shared biological pathways that underlie cognitive and mobility impairment remains an active area of research.

Our study provides novel data about risk of death associated with the development of incident mobility disability and incident MCI alone and sequentially. Prior studies have shown that mobility disability and cognitive impairment are each associated with mortality (29, 30), and the risk is highest among individuals with both slow gait and low cognition (31). However, as most of these studies consider only baseline measures, it was unclear whether the order of development of mobility disability and cognitive impairment alters the subsequent risk of death. We found that incident MCI alone increases the risk of death, but incident mobility disability alone does not. Relative to participants who were unimpaired, those who developed mobility disability alone showed little increase in risk of death, and the increase in the risk of death was only observed after they subsequently developed MCI. By contrast, participants who developed MCI alone had a higher risk of death than those who were unimpaired or developed only mobility disability, and there was no additional increase in the risk of death after developing subsequent mobility disability.

Our study applied a novel approach to examine associations of demographics with multiple correlated adverse events. Some demographic variables showed consistent associations across diverse impairment events; while others varied with specific impairments. Indeed, we found older age at baseline was associated with greater risk of incident mobility and/or incident MCI regardless of the order of occurrence, and it was also associated with death with or without impairment. On the other hand, we found significant sex difference in both incident mobility disability and incident MCI but interestingly in an opposite direction. In particular, female had a greater risk for incident mobility disability but male had a greater risk for incident MCI, and these associations were observed for participants with or without the other impairment. Male sex with higher incidence of MCI has been previously reported in a separate population-based cohort (32), but a majority of literature suggests that female have higher susceptibility to cognitive decline and dementia (33).

Strength and limitations are noted. To our knowledge, this is the first study that delineates incidences of mobility disability, MCI and death among community dwelling older adults, and examined how the order in which incident mobility disability and MCI occur is differentially associated with mortality. Annual assessments of gait and cognitive function allow us to follow participants’ impairment status longitudinally up to over two decades, and the follow-up rate among survivors is over 90%. Limitations include that ROSMAP are voluntary cohorts and a majority of the participants are non-Latino whites with high level of education. Finally, the ascertainment of mobility disability and cognitive impairment is quite different and the extent to which our assessments capture their respective constructs may differ. As a result, the head to head comparison of the difference in their incidences may need to be interpreted with caution.

Extended Data

e-Figure 1.

Associations of baseline age with incident impairment and death

e-Figure 2.

Associations of sex with incident impairment and death

Acknowledgement

The authors are deeply indebted to participants in the Religious Orders Study and the Rush Memory and Aging Project. The authors thank the investigators and staff at the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center. Data from ROS and MAP can be obtained through the RADC Research Resource Sharing Hub (www.radc.rush.edu).

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (P30AG10161, R01AG17917, R01AG56352, R01AG34374, R01AG33678) of the United States.

Footnotes

Statement of Ethics

Both the Religious Orders Study and the Rush Memory and Aging Project were approved by the institutional review board of the Rush University Medical Center. Each participant provided a written informed consent.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Verghese J, LeValley A, Hall CB, Katz MJ, Ambrose AF, Lipton RB. Epidemiology of gait disorders in community-residing older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006. February;54(2):255–61. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, Heeringa SG, Weir DR, Ofstedal MB, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Annals of internal medicine. 2008;148(6):427–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu WC, Chou MY, Peng LN, Lin YT, Liang CK, Chen LK. Synergistic effects of cognitive impairment on physical disability in all-cause mortality among men aged 80 years and over: Results from longitudinal older veterans study. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181741 PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verghese J, Wang C, Lipton RB, Holtzer R, Xue X. Quantitative gait dysfunction and risk of cognitive decline and dementia. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2007. September;78(9):929–35. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marquis S, Moore MM, Howieson DB, Sexton G, Payami H, Kaye JA, et al. Independent predictors of cognitive decline in healthy elderly persons. Archives of neurology. 2002. April;59(4):601–6. PubMed PMID: Epub 2002/04/10. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inzitari M, Newman AB, Yaffe K, Boudreau R, de Rekeneire N, Shorr R, et al. Gait speed predicts decline in attention and psychomotor speed in older adults: the health aging and body composition study. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29(3–4):156–62. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson NL, Rosano C, Boudreau RM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Executive function, memory, and gait speed decline in well-functioning older adults. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2010. October;65(10):1093–100. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atkinson HH, Rosano C, Simonsick EM, Williamson JD, Davis C, Ambrosius WT, et al. Cognitive function, gait speed decline, and comorbidities: the health, aging and body composition study. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2007. August;62(8):844–50. PubMed PMID: Epub 2007/08/19. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soumare A, Tavernier B, Alperovitch A, Tzourio C, Elbaz A. A cross-sectional and longitudinal study of the relationship between walking speed and cognitive function in community-dwelling elderly people. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2009. October;64(10):1058–65. PubMed PMID: Epub 2009/06/30. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett DA, Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Schneider JA. Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2018;64(s1):S161–S89. PubMed PMID: Epub 2018/06/06. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Leurgans SE, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Pulmonary function, muscle strength, and incident mobility disability in elders. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2009. December 1;6(7):581–7. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Leurgans SE, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Cognitive function is associated with the development of mobility impairments in community-dwelling elders. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011;19(6):571–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weidung B, Bostrom G, Toots A, Nordstrom P, Carlberg B, Gustafson Y, et al. Blood pressure, gait speed, and mortality in very old individuals: a population-based cohort study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2015. March;16(3):208–14. PubMed PMID: Epub 2014/12/03. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Evans DA, Beckett LA, Aggarwal NT, et al. Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology. 2002. July 23;59(2):198–205. PubMed PMID: Epub 2002/07/24. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, Arvanitakis Z, Shah RC, Kelly JF, et al. Decision rules guiding the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in two community-based cohort studies compared to standard practice in a clinic-based cohort study. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27(3):169–76. PubMed PMID: Epub 2006/10/13. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984. July;34(7):939–44. PubMed PMID: Epub 1984/07/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med. 2007. May 20;26(11):2389–430. PubMed PMID: Epub 2006/10/13. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):515–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Wreede LC, Fiocco M, Putter H. mstate: an R package for the analysis of competing risks and multi-state models. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;38(7): 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ensrud KE, Lui L-Y, Paudel ML, Schousboe JT, Kats AM, Cauley JA, et al. Effects of mobility and cognition on risk of mortality in women in late life: a prospective study. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2015;71(6):759–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardy SE, Perera S, Roumani YF, Chandler JM, Studenski SA. Improvement in usual gait speed predicts better survival in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007. November;55(11):1727–34. PubMed PMID: Epub 2007/10/06. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, Rosano C, Faulkner K, Inzitari M, et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. Jama. 2011;305(1):50–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toots A, Rosendahl E, Lundin-Olsson L, Nordstrom P, Gustafson Y, Littbrand H. Usual gait speed independently predicts mortality in very old people: a population-based study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013. July;14(7):529 e1–6. PubMed PMID: Epub 2013/05/28. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Beck TL, Kelly JF, Bennett DA. Apolipoprotein E e4 allele is associated with more rapid motor decline in older persons. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2009. Jan-March;23(1):63–9. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider JA, Li JL, Li Y, Wilson RS, Kordower JH, Bennett DA. Substantia nigra tangles are related to gait impairment in older persons. Ann Neurol. 2006. January;59(1):166–73. PubMed PMID: Epub 2005/12/24. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murray ME, Senjem ML, Petersen RC, Hollman JH, Preboske GM, Weigand SD, et al. Functional impact of white matter hyperintensities in cognitively normal elderly subjects. Archives of neurology. 2010. November;67(11):1379–85. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silbert LC, Nelson C, Howieson DB, Moore MM, Kaye JA. Impact of white matter hyperintensity volume progression on rate of cognitive and motor decline. Neurology. 2008. July 8;71(2):108–13. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchman AS, Yu L, Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Brain pathology contributes to simultaneous change in physical frailty and cognition in old age. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2014. December;69(12): 1536–44. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sachs GA, Carter R, Holtz LR, Smith F, Stump TE, Tu W, et al. Cognitive impairment: an independent predictor of excess mortality: a cohort study. Annals of internal medicine. 2011. September 6;155(5):300–8. PubMed PMID: Epub 2011/09/07. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ensrud KE, Lui LY, Paudel ML, Schousboe JT, Kats AM, Cauley JA, et al. Effects of Mobility and Cognition on Risk of Mortality in Women in Late Life: A Prospective Study. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2016. June;71(6):759–65. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosano C, Newman AB, Katz R, Hirsch CH, Kuller LH. Association between lower digit symbol substitution test score and slower gait and greater risk of mortality and of developing incident disability in well-functioning older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008. September;56(9):1618–25. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, Cha RH, Pankratz VS, Boeve BF, et al. The incidence of MCI differs by subtype and is higher in men: the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology. 2012. January 31;78(5):342–51. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snyder HM, Asthana S, Bain L, Brinton R, Craft S, Dubal DB, et al. Sex biology contributions to vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease: A think tank convened by the Women’s Alzheimer’s Research Initiative. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2016. November;12(11):1186–96. PubMed PMID: Epub 2016/10/04. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]