Abstract

Background

For diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) is one of the most widely used structured diagnostic interviews.

Methods

In this study, we aimed to develop and validate the Korean version of CAPS for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition ([DSM-5] K-CAPS-5). Seventy-one subjects with PTSD, 74 with mood disorder or anxiety disorder, and 99 as healthy controls were enrolled. The Korean version of the structured clinical interview for DSM-5-research version was used to assess the convergent validity of K-CAPS-5. BDI-II, BAI, IES-R, and STAI was used to evaluate the concurrent validity.

Results

All subjects completed various psychometric assessments including K-CAPS-5. K-CAPS-5 presented good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.92) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.91). K-CAPS-5 showed strong correlations with the structured clinical interview for DSM-5 PTSD (k = 0.893). Among the three subject groups listed above there were significant differences in the K-CAPS-5 total score. The data were best explained by a six-factor model.

Conclusion

These results demonstrated the good reliability and validity of K-CAPS-5 and its suitability for use as a simple but structured instrument for PTSD assessment.

Keywords: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale, Validity, Reliability, Korean

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale (CAPS) is the gold standard and one of the most widely used structured diagnostic interviews of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).1,2 CAPS for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition ([DSM-5] CAPS-5)3 is a 30-item questionnaire and the full interview takes 45–60 minutes. The instrument allows quantification of the frequency and intensity of the 20 PTSD symptoms according to DSM-5.4 In addition to evaluating the 20 DSM-5 PTSD symptoms, the other 10 questions address the index trauma event, duration of symptoms, subjective distress, influence of symptoms on social and occupational functioning, overall response validity, overall PTSD severity, improvement in PTSD symptoms since a previous CAPS administration, and specifications for the dissociative subtype.

Several important revisions were made to the CAPS in updating it for DSM-5. First, CAPS for DSM-5 asked respondents to keep in mind three traumatic events during the interview. But, CAPS-5 uses the identification of a single index trauma to serve as the basis of symptom inquiry. Second, CAPS-5 is corresponding to the DSM-5 diagnosis for PTSD. The expression of the CAPS-5 included both changes to existing symptoms and the addition of new symptoms in DSM-5. CAPS-5 assesses the dissociative subtype of PTSD (depersonalization and derealization), but no longer evaluates other associated symptoms (e.g., gaps in awareness). Third, as with the CAPS for DSM-5, CAPS-5 symptom severity ratings relied on symptom frequency and intensity. However, CAPS-5 items are rated with a single severity score in contrast to the CAPS for DSM-5 which required separate frequency and intensity scores. Fourth, the CAPS-5 includes general instructions and scoring information.3

Structured interviews used to diagnose PTSD include the PTSD Interview, the Structured Interview for PTSD, and CAPS. The PTSD Interview is a questionnaire format, so it can be influenced by the response of the subject and there is a limitation in that an inaccurate self-evaluation may lead to a deviation.5 The Structured Interview for PTSD has the disadvantage of diagnosing PTSD based on the worst memory of the whole life.6 CAPS has a disadvantage that it takes a lot of time for testing and it is not valid for non-experts to inspect. However, because symptoms of PTSD are clearly distinguished by frequency and intensity, they are widely used in research and clinical fields in the world.3

In CAPS-5, the Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5)7 is recommended to identify an index traumatic event. LEC-5 covered various stressful events such as natural disaster, fire or explosion, transportation accident, serious accident, exposure to toxic substance, physical assault, sexual assault, combat, life-threatening illness and so on. In addition, LEC-5 can distinguish the experience of index trauma by whether subjects undergo index trauma, whether subjects witnessed index trauma, whether index trauma happened to a person close to the subjects, and whether subjects experienced occupational index trauma. CAPS-5 symptoms cluster severity scores are calculated by summing each item severity score for symptoms corresponding to the intrusion, avoidance, cognition/mood, and arousal/reactivity clusters. The intrusion, avoidance, cognition/mood, and arousal/reactivity clusters consist of 5, 2, 7 and 6 items, respectively. CAPS-5 is divided into three versions according to the period; past week, past month, and worst month. Because CAPS-5 faithfully reflects DSM-5, PTSD can be diagnosed if it involves one or more intrusion symptoms, one or more avoidance symptoms, two or more cognition/mood symptoms, two or more arousal/reactivity symptoms, a period of one month or more, and significant distress or functional impairment.4

Although the CAPS for DSM-5 had excellent psychometric properties8,9 and has been standardized in Korean,10 many changes were made to the PTSD diagnosis in DSM-5. While PTSD used to be categorized with the anxiety disorders in DSM-5, it now has been moved into a separate chapter called “Trauma- and Stress-Related Disorders” in DSM-5. Further, although the duration of the diagnosis has not been changed, the PTSD symptoms, which were classified into three categories of reexperience, avoidant/numbing and hyper-arousal in DSM-5, have been re-classified into 4 clusters of intrusion, avoidance, cognition/mood, and arousal/reactivity in DSM-5.4 These changes necessitate standardization of CAPS-5 for a Korean version.

In this study, we aimed to develop and validate the Korean version of CAPS-5 (K-CAPS-5). After translating CAPS-5 into Korean language while maintaining its basic structure, we assessed the validity and the reliability of K-CAPS-5 for testing the usefulness in Korean PTSD patients.

METHODS

Subjects

A total of 274 subjects were recruited from 8 medical institutions throughout Korea, from February 2016 until March 2017. The 274 study subjects comprised 71 with PTSD, 74 with mood disorder or anxiety disorder as a psychiatric control group, and 99 as a healthy control group. PTSD and other psychiatric disorders were diagnosed by the structured clinical interview for DSM-5-research version (SCID-5-RV).11 The SCID-5-RV is a semi-structured interview guide for making DSM-5 diagnoses, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Interviewer training consisted of lectures on the SCID-5-RV and related questionnaires, observation of an evaluation performed by an experienced psychiatrist, and group evaluation of videos of PTSD patients. The diagnoses of subjects in the psychiatric control included major depressive disorder (n = 44), panic disorder (n = 6), and generalized anxiety disorder (n = 24). The healthy control group included 88 randomly selected individuals visiting the institutions for regular health screening. All the healthy controls demonstrated that they did not have a lifetime history of psychiatric disorders in SCID-5-RV.

Exclusion criteria for psychiatric disorders were being younger than 18 or older than 70 years, having been diagnosed with a present or past diagnosis of psychotic disorders, and were not able to complete the CAPS-5 interview. To assess test-retest reliability, only the PTSD patients with stable PTSD symptoms and who agreed to a second K-CAPS-5 assessment were included.

Measurement instruments

After obtaining permission from the National Center for PTSD, three bilingual psychiatrists and one psychologist in English and Korean initially translated CAPS-5; this was followed by a process of back translation and revisions. Two other bilingual Korean psychiatrists and one psychologist performed the back translation blindly. Finally, a translation committee, which consisted of five Korean psychiatrists, one Korean language and literature professor, and one psychologist, made the final version of K-CAPS-5.

The Korean version of SCID-5-RV (K-SCID-RV) was used to assess the convergent validity of K-CAPS-5. We used SCID-RV as the gold standard assessment of DSM-5 PTSD. SCID-5-RV is a semi-structured interview guide for making DSM-5 diagnoses for depression, anxiety and PTSD. It was administered by trained mental health professionals that were familiar with the DSM-5 classification and diagnostic criteria.

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II),12 the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI),13 the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R),14 and the Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)15 were also performed to assess the correlations with the scores of K-CAPS-5. BDI-II, a 21-item self-administered questionnaire, was designed to evaluate the severity of depression, and BAI with 21 items for evaluating the severity of anxiety. IES-R, a 22-item self-reporting questionnaire composed 8 questions for intrusion, 8 for avoidance, and 6 for hyperarousal, was used to assess the severity of PTSD symptoms. STAI, with 40 self-check questions, was developed to assess the severity of state anxiety and trait anxiety. The Korean versions of BDI, BAI, IES-R and STAI have previously been shown to exhibit excellent psychometric properties, and their internal consistency coefficients were reported to be 0.85,16 0.90,17 0.76,18 and 0.91,19 respectively.

The 8 interviewers in this study were skilled board-certificated psychiatrists and clinical psychologists with careers in PTSD practice of at least five years. The consensus meeting consisted of lecturing on K-CAPS-5 and related questionnaire characteristics, observing the evaluation by an experienced psychiatrist, and evaluating the video-recorded PTSD patients together. The inter-rater reliability values of the PTSD module of SCID-RV and K-CAPS-5 were high, with intra-class correlation coefficients of 0.74 and 0.80, respectively.

Statistical analyses

Among the PTSD, psychiatric control, and normal control groups, demographic variables and clinical characteristics were compared using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and χ2 analyses to compare the quantitative and categorical variables. In order to measure the internal consistencies of K-CAPS-5, Cronbach's alpha coefficients were computed, and the item-total correlation coefficients of these scales were measured to confirm that all the items on these scales also exhibited internal consistency. Test-retest reliability and the inter-rater reliability were calculated by means of the intraclass correlation coefficients. Test-retest reliability was evaluated by the same interviewers who performed the two testing sessions within 5 days. To measure the agreement of each item between K-CAPS-5 and SCID-5-RV, Pearson's χ2 and Cohen's κ coefficient were calculated. Cohen's κ coefficient ranges from 0 to 1; values of 0.8 and over are considered to indicate ‘good agreement’ and values of 0.6–0.8 are considered to indicate substantial agreement.20 Pearson correlation coefficients were used to evaluate the concurrent validity between K-CAPS-5, BDI-II, BAI, IES-R, and STAI. ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test was performed to evaluate the between-group difference by the severity measured by K-CAPS-5. An exploratory factor analysis was performed using principal component analysis with varimax rotation to determine the factor structure of K-CAPS-5. The optimal cutoff scores of K-CAPS-5 that best predicted current PTSD by SCID-5-RV were estimated by receiver operating characteristics curve analysis. The sensitivities, specificities, positive predictive values, negative predictive values, and κ values were measured for each threshold score of K-CAPS-5.

Analyses were performed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the public Institutional Review Board of the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea (P01-201508-21-002). All subjects were informed of the study purpose and methods and provided written informed consent.

RESULTS

Demographics and clinical characteristics

The mean ages of the PTSD, psychiatric control, and normal control groups were 46.9 (standard deviation [SD], 14.3), 43.7 (SD, 12.1), and 44.6 (SD, 9.2) years, respectively. The numbers of males in the three groups were 42 (60.0%), 34 (45.9%), and 37 (37.4%), respectively. No significant differences were found for age (F = 1.433, P = 0.241), although a significant difference in gender ratio was found among the three groups (χ2 = 8.452, P = 0.015). There was no significant difference in marital status among the three groups. The mean duration of symptoms in the PTSD group was 22.31 (SD, 29.17; range, 1.10–126.67) months. The worst traumas experienced in the PTSD group were serious accidents, such as automobile or man-made disasters (n = 51, 72.9%), physical assault (n = 7, 10.0%), sexual abuse (n = 6, 28.6%), combat experience (n = 2, 2.9%), life-threating medical disease (n = 2, 2.9%), and witnessing an accident (n = 2, 2.9%).

Reliability

Cronbach's α was used to evaluate the internal consistency of K-CAPS-5 in the 71 PTSD patients. Internal consistency for the K-CAPS-5 total score was 0.92 at baseline. Alpha coefficients for intrusion, avoidance, cognition/mood, and arousal/reactivity were 0.83, 0.71, 0.82, and 0.75, respectively. Based on the criterion of 0.30 as an acceptable corrected item-total correlation,19 all 20 items performed adequately (range, 0.38–0.79) (Table 1).

Table 1. Item-total correlation of K-CAPS-5.

| Variables | Pearson correlation | P value |

|---|---|---|

| B1: intrusive memory | 0.719 | < 0.001 |

| B2: distressing dreams | 0.657 | < 0.001 |

| B3: flashbacks | 0.444 | < 0.001 |

| B4: cued psychological | 0.734 | < 0.001 |

| B5: cued physiological reaction | 0.759 | < 0.001 |

| C1: avoidance of memories | 0.639 | < 0.001 |

| C2: avoidance of external reminders | 0.626 | < 0.001 |

| D1: dissociative amnesia | 0.380 | < 0.001 |

| D2: negative belief | 0.658 | < 0.001 |

| D3: distorted blame | 0.621 | < 0.001 |

| D4: negative emotional state | 0.790 | < 0.001 |

| D5: diminished interest | 0.648 | < 0.001 |

| D6: detachment from others | 0.593 | < 0.001 |

| D7: no positive emotions | 0.633 | < 0.001 |

| E1: irritability/aggression | 0.676 | < 0.001 |

| E2: reckless/self-destructive | 0.451 | < 0.001 |

| E3: hypervigilance | 0.546 | < 0.001 |

| E4: exaggerated startle response | 0.607 | < 0.001 |

| E5: poor concentration | 0.752 | < 0.001 |

| E6: sleep disturbance | 0.594 | < 0.001 |

K-CAPS-5 = Korean Version of Clinician-Administered Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Scale for DSM-5.

Among the 71 PTSD subjects, 34 were recruited for the evaluation of the test-retest reliability. The test-retest reliability was determined to be 0.91 (P < 0.001).

Validity

The total scores ± standard error (SE) of K-CAPS-5 in the PTSD group, the psychiatric controls and normal controls were 33.03 ± 1.07, 18.00 ± 9.79, and 6.18 ± 5.86, respectively. These values were significantly different by ANOVA (overall F = 115.87, P < 0.001). The Tukey's post-hoc test showed that there were significant differences among the three groups. These results showed the good construct validity of K-CAPS-5.

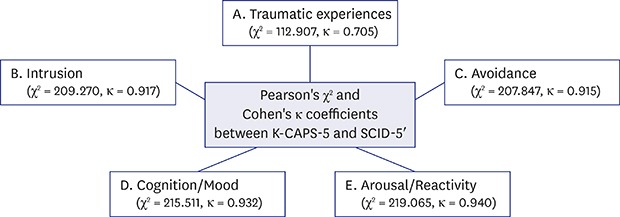

Table 2 shows the value of Pearson's χ2 and Cohen's κ coefficient between K-CAPS-5 and SCID-5. Both PTSD diagnosis (κ = 0.893) and dissociative subtype of PTSD were in almost perfect agreement (κ = 0.839). According to the detailed diagnosis criteria, Cohen's κ coefficient of traumatic experience was 0.705, which corresponds to substantial agreement, and Cohen's κ coefficients of intrusion, avoidance, cognition/mood, and arousal/reactivity were all more than 0.910, which were in almost perfect agreement.

Table 2. Pearson's χ2 and Cohen's κ coefficients between K-CAPS-5 and SCID-5.

| Variables | χ2 | P value | κ (SE) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: traumatic experiences | 112.907 | < 0.001 | 0.705 (0.048) | < 0.001 |

| B: intrusion | 209.270 | < 0.001 | 0.917 (0.026) | < 0.001 |

| B1: intrusive memory | 132.734 | < 0.001 | 0.923 (0.031) | < 0.001 |

| B2: distressing Dreams | 141.792 | < 0.001 | 0.955 (0.025) | < 0.001 |

| B3: flashbacks | 113.251 | < 0.001 | 0.852 (0.072) | < 0.001 |

| B4: cued psychological | 132.734 | < 0.001 | 0.923 (0.031) | < 0.001 |

| B5: cued physiological reaction | 128.792 | < 0.001 | 0.908 (0.034) | < 0.001 |

| C: avoidance | 207.847 | < 0.001 | 0.915 (0.026) | < 0.001 |

| C1: avoidance of memories | 119.889 | < 0.001 | 0.872 (0.039) | < 0.001 |

| C2: avoidance of external reminders | 116.759 | < 0.001 | 0.859 (0.041) | < 0.001 |

| D: cognition/mood | 215.511 | < 0.001 | 0.932 (0.024) | < 0.001 |

| D1: dissociative amnesia | 105.282 | < 0.001 | 0.812 (0.074) | < 0.001 |

| D2: negative belief | 133.186 | < 0.001 | 0.912 (0.035) | < 0.001 |

| D3: distorted blame | 140.897 | < 0.001 | 0.940 (0.030) | < 0.001 |

| D4: negative emotional state | 143.770 | < 0.001 | 0.950 (0.025) | < 0.001 |

| D5: diminished interest | 133.278 | < 0.001 | 0.912 (0.032) | < 0.001 |

| D6: detachment from others | 139.134 | < 0.001 | 0.933 (0.029) | < 0.001 |

| D7: no positive emotions | 140.131 | < 0.001 | 0.937 (0.028) | < 0.001 |

| E: arousal/reactivity | 219.065 | < 0.001 | 0.940 (0.022) | < 0.001 |

| E1: irritability/aggression | 146.671 | < 0.001 | 0.969 (0.022) | < 0.001 |

| E2: reckless/self-destructive | 156.000 | < 0.001 | 1.000 (0.000) | < 0.001 |

| E3: hypervigilance | 151.844 | < 0.001 | 0.987 (0.013) | < 0.001 |

| E4: exaggerated startle response | 135.474 | < 0.001 | 0.930 (0.031) | < 0.001 |

| E5: poor concentration | 137.187 | < 0.001 | 0.938 (0.028) | < 0.001 |

| E6: sleep disturbance | 126.061 | < 0.001 | 0.896 (0.036) | < 0.001 |

| Duration of symptoms | 200.940 | < 0.001 | 0.902 (0.031) | < 0.001 |

| Subjective distress | 64.967 | < 0.001 | 0.626 (0.061) | < 0.001 |

| Influence of symptoms on social functioning | 82.599 | < 0.001 | 0.719 (0.055) | < 0.001 |

| Influence of symptoms on occupational functioning | 109.282 | < 0.001 | 0.834 (0.044) | < 0.001 |

| Depersonalization | 141.097 | < 0.001 | 0.954 (0.047) | < 0.001 |

| Derealization | 107.660 | < 0.001 | 0.820 (0.087) | < 0.001 |

| PTSD diagnosis | 197.548 | < 0.001 | 0.893 (0.033) | < 0.001 |

| With dissociation | 110.163 | < 0.001 | 0.839 (0.070) | < 0.001 |

K-CAPS-5 = Korean Version of Clinician-Administered Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Scale for DSM-5, SCID = structured clinical interview DSM, SD = standard error, PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

The total K-CAPS-5 score was correlated with BDI (r = 0.58, P < 0.001), BAI (r = 0.67, P < 0.001), IES-R (r = 0.78, P < 0.001), and STAI-T (r = 0.37, P = 0.003). Thus, the correlation of K-CAPS-5 was strong with IES-R, relatively weak with STAI-T, and intermediated with BDI-II (Table 3).

Table 3. Pearson's correlations among K-CAPS-5, BAI, IES-R, and STAI in PTSD patients.

| Variables | K-CAPS-5 | BDI | BAI | IES-R | STAI-S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI | 0.584a | - | - | - | - |

| BAI | 0.673a | 0.701a | - | - | - |

| IES-R | 0.776a | 0.808a | 0.845a | - | - |

| STAI-S | 0.123 | 0.029 | 0.296b | 0.416b | - |

| STAI-T | 0.365b | 0.104 | 0.249b | 0.377b | 0.724a |

K-CAPS-5 = the Korean version of clinicians Administered PTSD Scale, BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory, IES-R = Impact of Event Scale-Revised, STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-state anxiety, PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder, BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, STAI-S = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-state anxiety subscale, STAI-T = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-trait anxiety subscale.

aP < 0.001; bP < 0.05.

The explorative factor analysis with varimax rotation on the items of K-CAPS-5 for the 71 subjects from the PTSD group yielded six factors that explained the results and which together accounted for 61.91% of the variance (Table 4). Given the contents, the first factor, which consisted of six items (D5 [diminished interest], D6 [detachment from others], D4 [negative emotional state], D7 [no positive emotions], D2 [negative belief], and D3 [distorted blame]), could be interpreted as a dimension of “negative affect in cognition and moods” (eigenvalue, 2.54; percentage of variance, 12.72%). Similarly, the second factor covered five items (B3 [flashbacks], B5 [cued physiological reaction], B4 [cued psychological], B1 [intrusive memory], and D1 [dissociative amnesia]) and was related to “intrusion” (eigenvalue, 2.48; percentage of variance, 12.42%). The third factor consisted of four items (E5 [poor concentration], E1 [irritability/aggression], E2 [reckless/self-destructive], and E4 [exaggerated startle response]) and was related to “alteration in reactivity” (eigenvalue, 2.20; percentage of variance, 10.98%). The fourth factor consisted of two items (C2 [avoidance of external reminders] and C1 [avoidance of memories]) and was related to “avoidance” (eigenvalue, 1.76; percentage of variance, 8.82%). The fifth factor consisted of two items (E6 [sleep disturbance] and B2 [distressing dreams]), and was loaded on “sleep disturbance” (eigenvalue, 1.70; percentage of variance, 8.50%). The sixth factor consisted of one item (E3 [hypervigilance]) and was loaded on “hyperarousal” (eigenvalue, 1.69; percentage of variance, 8.47%).

Table 4. Explorative factor analysis on the items of K-CAPS-5 in PTSD patients.

| Variables | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Factor 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D5: diminished interest | 0.713 | - | - | - | - | - |

| D6: detachment from others | 0.661 | - | - | - | - | - |

| D4: negative emotional state | 0.629 | - | - | - | - | - |

| D7: no positive emotions | 0.612 | - | - | - | - | - |

| D2: negative belief | 0.605 | - | - | - | - | - |

| D3: distorted blame | 0.417 | - | - | - | - | - |

| B3: flashbacks | - | 0.781 | - | - | - | - |

| B5: cued physiological reaction | - | 0.698 | - | - | - | - |

| B4: cued psychological | - | 0.691 | - | - | - | - |

| B1: intrusive memory | - | 0.670 | - | - | - | - |

| D1: dissociative amnesia | - | 0.531 | - | - | - | - |

| E5: poor concentration | - | - | 0.640 | - | - | - |

| E1: irritability/aggression | - | - | 0.591 | - | - | - |

| E2: reckless/self-destructive | - | - | 0.586 | - | - | - |

| E4: exaggerated startle response | - | - | 0.076 | - | - | - |

| C2: avoidance of external reminders | - | - | - | 0.552 | - | - |

| C1: avoidance of memories | - | - | - | 0.450 | - | - |

| E6: sleep disturbance | - | - | - | - | 0.826 | - |

| B2: distressing Dreams | - | - | - | - | 0.730 | - |

| E3: hypervigilance | - | - | - | - | - | 0.896 |

| Percent of variance | 12.72 | 12.42 | 10.98 | 8.82 | 8.50 | 8.47 |

| Eigenvalue | 2.54 | 2.48 | 2.20 | 1.76 | 1.70 | 1.69 |

K-CAPS-5 = the Korean version of clinicians Administered PTSD Scale, PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

DISCUSSION

CAPS-5 is a current tool that should be standardized for PTSD studies because it clearly measures the severity of PTSD symptoms, despite its disadvantages of taking a lot of time and not being valid for non-specialists. Unlike previous versions, no study has validated CAPS-5. This study developed K-CAPS-5 using various tools, including SCID-5-RV, and presented good reliability and validity.

In this study, K-CAPS-5 presented good reliability. The excellent internal consistency of K-CAPS-5 was demonstrated by Cronbach's α of 0.92.21,22,23 The coefficient of the four PTSD symptom clusters was within the optimal range, considering that an optimal value of α should be between 0.70 and 0.90.24 The test-retest reliability of K-CAPS-5 was determined to be 0.91. The test-retest interval in this study was two weeks. In clinical situations, longer test-retest intervals might cause greater PTSD symptom changes. Most of the PTSD subjects included in this study were chronic types whose mean duration of symptoms was 4.2 years, and no subject presented any PTSD symptom changes. Thus, we could conclude that K-CAPS-5 has good reliability.

The PTSD diagnoses of K-CAPS-5 and SCID-5-RV were in substantial agreement (κ = 0.893). Most items of K-CAPS-5 and SCID-5-RV were in almost perfect agreement (κ > 0.81), except a few items such as subjective distress, and influence of symptoms on social functioning (κ = 0.61–0.80). In SCID-5-RV, the symptom-related distress or functional impairment was evaluated as one item. On the other hand, in K-CAPS-5, the item was evaluated as three items: Subjective distress, Influence of symptoms on social functioning and Influence of symptoms on occupational functioning. The agreement of functional impairment may be reduced because of the differences in these evaluation methods. Thus, K-CAPS-5 could be ideal for diagnosing PTSD.

In the comparison of the three groups of severity scores of K-CAPS-5, the PTSD group showed the highest average, followed by the psychiatric control and normal groups. K-CAPS-5 includes cognition/mood items, as well as other items such as intrusion, avoidance, and arousal/reactivity. In addition, the CAPS for DSM-4 was known as being partially correlated with depressive or anxiety disorders, so the total severity scores of the CAPS-5 score of the psychiatric control group were higher than those of the normal control group.10

K-CAPS-5 was highly correlated with IES-R in the similar constructs, but less strongly correlated with other less relevant measuring constructs, such as depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms. Also, K-CAPS-5 was not correlated with STAI-S. These correlations demonstrate the reasonable discriminant validity of this task as a measure for assessing PTSD symptoms. This result was similar to the results of one previous study conducted in Korea on the CAPS for DSM-IV standardization.10

In the factor analysis of K-CAPS-5, six factors were generated though the explained variance (61.91%). The six-factor model differed from the diagnostic criteria of DSM-5 PTSD. Other researchers have suggested six- or seven-factor model that are the anhedonia model,24 externalizing behavior model,25 and hybrid model.26 There was no change in the four factors of DSM-5 PTSD, because the six- or seven-factor model of PTSD divided “negative alterations in cognitions and mood” and “alterations in arousal and reactivity” criteria in detail. However, in this study, sleep disturbance and hyperarousal were analyzed as two new factors. Because sleep disturbances such as insomnia and nightmares are core components of PTSD,27 sleep disturbance might be separated as a new factor. Several studies suggested that the separation of hyperarousal from “arousal/reactivity” might be appropriate.28,29,30,31,32,33,34 Because the results of this study may be due to the small number of PTSD subjects, factor analysis with more subjects is needed.

Several limitations of the present study should be considered. First, the number of the index traumatic events of the PTSD group were relatively small; thus no difference among the PTSD symptoms could be distinguished according to each index traumatic event. Second, the proportion of males in the PTSD group was higher than that in the other groups. Women are more vulnerable to PTSD and are more likely to develop PTSD than men,35 so a future study with a slightly higher proportion of women with PTSD will be more representative. Finally, the normal group did not experience any traumatic event that satisfies the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria A of PTSD. In one previous study, patients who experienced the same traumatic event were compared with the PTSD and control groups to evaluate the reliability and validity of CAPS.35

In conclusion, K-CAPS-5 had good psychometric properties and may be used as a reliable and valid instrument to diagnose and assess PTSD according to DSM-5. More studies are needed to compare patients with PTSD and control in the same index traumatic event with CAPS-5.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a grant of the Korean Mental Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HM15C1058).

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Kim WH, Park JE.

- Formal analysis: Kim WH, Park JE.

- Investigation: Jung YE, Roh D, Kim D, Kang SH, Park JE.

- Methodology: Kim WH, Park JE.

- Resources: Jung YE, Roh D, Kim D, Kang SH, Park JE.

- Software: Kim WH, Park JE.

- Supervision: Park JE, Kim D, Chae JH.

- Validation: Park JE, Kim D, Roh D, Chae JH.

- Visualization: Kim WH.

- Writing - original draft: Kim WH.

- Writing - review & editing: Park JE, Kim D, Roh D.

References

- 1.Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, et al. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8(1):75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, et al. A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: the CAPS-1. Behav Ther. 1990;13:187–188. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weathers FW, Bovin MJ, Lee DJ, Sloan DM, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, et al. The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychol Assess. 2018;30(3):383–395. doi: 10.1037/pas0000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulk RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Jordan BK, Hough RL, Marmar CR, et al. Trauma and the Vietnam War Generation: Report of Findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L. Traumatic Stress. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weathers FW, Blake DD, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Marx BP, Keane TM. The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) [Updated 2013]. [Accessed December 15, 2017]. http://www.ptsd.va.gov.

- 8.Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychol Assess. 1999;11(2):124–133. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orsillo SM. Measures for acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Antony MM, Orsillo SM, editors. Practitioner's Guide to Empirically Based Measures of Anxiety. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee BY, Kim Y, Yi SM, Eun HJ, Kim DI, Kim JY. A reliability and validity study of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1999;38(3):514–522. [Google Scholar]

- 11.First MB, Williams JB, Karg RS, Spitzer RL. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5-Research Version (SCID-5 for DSM-5, Research Version; SCID-5-RV) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The impact of event scale–revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL. State-trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhee MK, Lee YH, Park SH, Sohn CH, Hong SK, Lee BK, et al. A standardization study of Beck depression inventory I; Korean version (K-BDI): reliability and factor analysis. Korean J Psychopathol. 1995;4(1):77–95. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho Y, Kim EJ. Psychometric properties of the Korean version of the Anxiety Control Questionnaire. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2004;23(2):503–518. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eun HJ, Kwon TW, Lee SM, Kim TH, Cho MR, Cho SJ. A study on reliability and validity of the Korean version of Impact of Event Scale-Revised. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2005;44(3):303–310. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hahn DW, Lee CH, Chon KK. Korean adaptation of Spielberger's STAI (K-STAI) Korean J Health Psychol. 1996;1(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kline P. The Handbook of Psychological Testing. 2nd ed. London: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeVellis RF. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nunnally JC. Introduction to Psychological Measurement. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu P, Wang L, Cao C, Wang R, Zhang J, Zhang B, et al. The underlying dimensions of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in an epidemiological sample of Chinese earthquake survivors. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(4):345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai J, Harpaz-Rotem I, Armour C, Southwick SM, Krystal JH, Pietrzak RH. Dimensional structure of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):546–553. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armour C, Contractor A, Shea T, Elhai JD, Pietrzak RH. Factor Structure of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5: relationships among symptom clusters, anger, and impulsivity. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016;204(2):108–115. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nardo D, Högberg G, Jonsson C, Jacobsson H, Hällström T, Pagani M. Neurobiology of sleep disturbances in PTSD patients and traumatized controls: MRI and SPECT findings. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:134. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Contractor AA, Durham TA, Brennan JA, Armour C, Wutrick HR, Frueh BC, et al. DSM-5 PTSD's symptom dimensions and relations with major depression's symptom dimensions in a primary care sample. Psychiatry Res. 2014;215(1):146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armour C, Carragher N, Elhai JD. Assessing the fit of the Dysphoric Arousal model across two nationally representative epidemiological surveys: The Australian NSMHWB and the United States NESARC. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(1):109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harpaz-Rotem I, Tsai J, Pietrzak RH, Hoff R. The dimensional structure of posttraumatic stress symptomatology in 323,903 U.S. veterans. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;49:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reddy MK, Anderson BJ, Liebschutz J, Stein MD. Factor structure of PTSD symptoms in opioid-dependent patients rating their overall trauma history. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(3):597–602. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang M, Armour C, Li X, Dai X, Zhu U, Yao S. Further evidence for a five-factor model of PTSD: factorial invariance across gender in Chinese earthquake survivors. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201(2):145–152. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31827f627d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tolin DF, Foa EB. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(6):959–992. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weathers FW, Blake DD, Krinsley KE, Haddad W, Huska JA, Keane TM. The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS): Reliability and Construct Validity. Boston, MA: Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy; 1992. [Google Scholar]