Abstract

Studies have indicated that chronic low back pain (LBP) should be approached according to its morphological basis and in consideration of biopsychosocial interventions. This study presents an updated review on available psychological assessments and interventions for patients with chronic LBP. Psychosocial factors, including fear-avoidance behavior, low mood/withdrawal, expectation of passive treatment, and negative pain beliefs, are known as risk factors for the development of chronic LBP. The Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire, STarT Back Screening Tool, and Brief Scale for Psychiatric Problems in Orthopaedic Patients have been used as screening tools to assess the development of chronicity or identify possible psychiatric problems. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale, Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire, and Injustice Experience Questionnaire are also widely used to assess psychosocial factors in patients with chronic pain. With regard to interventions, the placebo effect can be enhanced by preferable patient-clinician relationship. Reassurance to patients with non-specific pain is advised by many guidelines. Cognitive behavioral therapy focuses on restructuring the negative cognition of the patient into realistic appraisal. Mindfulness may help improve pain acceptance. Self-management strategies with appropriate goal setting and pacing theory have proved to improve long-term pain-related outcomes in patients with chronic pain.

Keywords: Chronic pain, Low back pain, Psychosocial strategy

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a major public health problem worldwide. Diagnosing the cause of LBP, which is usually defined as pain localized below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds, is essential to the triage of patients with specific or non-specific LBP1). Regardless of the established guideline for treating LBP1), approximately 5% to 10% of LBP may develop into chronic conditions after various interventions2-4). Studies using imaging to identify the morphological pathology of LBP have reported high rates of false-positive results5). Inoue et al. reported that approximately 20% patients who underwent lumbar surgery have residual symptoms, among which pain is the most prevalent6). A recent report in Japan has indicated that psychosocial factors are critical to the development of chronic, disabling LBP7). As such, chronic LBP should be approached by considering not only its morphological basis but also its biopsychosocial interventions8-10).

Brox et al. reported that lumbar fusion surgery for chronic LBP after a previous surgery is no more effective than cognitive intervention11), indicating that clinicians should recognize the importance of biopsychosocial interventions and identify the fundamental technique for treating patients with chronic LBP. However, few facilities in Japan can provide biopsychosocial interventions for chronic pain, and thus, the standard technique of psychological intervention for chronic pain seems to be lacking among Japanese clinicians12). In the present work, we present an updated review as keynote on the available psychological assessments and interventions for patients with chronic LBP.

Psychological Treatment Strategy

1. Assessment of physical problems and disabilities

Prior to psychological assessment, it is essential for the clinicians to reevaluate physical problems to avoid overlooking red flags or organic diseases. Nonetheless, it seems inevitable that diagnostic errors often occur because of cognitive biases, such as availability, representativeness, confirmation bias, and premature disclosure13). For example, although vertebral fracture is one of prevalent causes of LBP, it is often overlooked14). An early intervention for osteoporosis with fragile vertebral fractures can be useful for preventing the development of chronic LBP15). While treatable organic diseases are sufficiently intervened, clinicians simultaneously need to assess the disabilities and quality of life (QOL) of patients with chronic LBP because improvements in disabilities are considered an important outcome among chronic pain patients16). The Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire17,18), Oswestry Disability Index19,20), and Pain Disability Assessment Scale21,22) are often used as assessment tools regarding disabilities in patients with chronic LBP.

2. Assessment of psychological risk factors

Psychosocial factors, including fear-avoidance behavior, low mood/withdrawal, expectation of passive treatment, and negative pain beliefs such as catastrophizing, have been known to be risk factors for the development of chronic LBP23-25), also known as “yellow flags” (Table 1). Linton et al. introduced the Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire (ÖMPQ) to assess psychosocial factors associated with acute LBP, and this questionnaire has been shown to be effective in predicting LBP chronicity26). As for a Japanese version of ÖMPQ, a short version of ÖMPQ was recently introduced27). In terms of clinical cut-off point, a total score of ≥72 in the ÖMPQ-12 short form or ≥114 in the ÖMPQ original 21-item form indicates a high risk of absenteeism or functional impairment, respectively28,29). Alternatively, Hill et al. introduced the Keele STarT Back Screening Tool to identify prognostic indicators to classify patients with poor prognoses30). A stratified approach using this screening was associated with a mean increase in generic health and cost savings31). Matsudaira et al. evaluated the validity of the Japanese version of STarT Back Screening (STarT-J) in patients with LBP32,33), and they reported the efficacy of STarT-J in predicting pain and disability outcomes after six months in patients with LBP34). This tool classifies patients into three risk groups based on scores on nine overall items and five psychosocial subscales as follows: the low-, medium-, and high-risk groups for those earning the total scores of 0-3, ≥4 (and psychosocial score of ≤3), and ≥4 (and psychosocial score of ≥4), respectively34). For patients in the high-risk group, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), in combination with physical therapy, is recommended35).

Table 1.

Screening Tool of Psychosocial Factors Associated with Chronic Low Back Pain.

| Questionnaire (abbreviation) | Evaluation issues | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire (ÖMPQ) | Psychosocial factors | |

| ÖMPQ original 21-item | A total score ≥ 114 indicates high risk of chronicity | |

| ÖMPQ-12 short form | A total score ≥ 72 indicates high risk of chronicity | |

| STarT Back Screening Tool | Psychosocial factors | A total score ≥ 4 with a psychosocial score ≥ 4 is high-risk of chronicity |

| Brief Scale for psychiatric problem in Orthopaedic Patients (BS-POP) | Psychiatric problems | Possible psychiatric problem: |

| A score ≥ 11 physician version points | ||

| or | ||

| A score ≥ 10 physician version points with a score ≥ 15 patient version points. | ||

| Pain catastrophizing scale (PCS) | Catastrophic thought for pain | Higher score indicates having higher catastrophizing thoughts (negative outcome). |

| Injustice Experience Questionnaire (IEQ) | Feeling of Injustice | Higher score indicates having higher injustice feelings (negative outcome). |

| Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) | Self-confidence to cope with pain | Higher score indicates having higher self-confidence (positive outcome). |

In addition, pain catastrophizing, pain coping skills, self-efficacy, and perceived injustice are known to be important psychometric properties associated with pain-related outcomes in patients with chronic pain36-38), and over 1,000 international studies have documented a relationship between pain catastrophizing and adverse pain outcomes39). The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS)40), Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ)41), and Injustice Experience Questionnaire (IEQ)38) are widely used to assess the psychosocial aspects of chronic pain patients worldwide, and their Japanese versions have been introduced and validated42-45).

Meanwhile, traditional psychiatric problems, such as anxiety and depression, are well known to be associated with sustained LBP46). Japanese orthopedic physicians have originally proposed the Brief Scale for Psychiatric problems in Orthopaedic Patients (BS-POP) to assess psychiatric problems in patients with LBP47,48). BS-POP includes questionnaires for both physicians and patients, and its clinical cut-off point to suspect psychiatric problem is set at ≥11 physician version points and ≥10 physician version points with ≥15 patient version points. Orthopedic surgeons are recommended to consult with a psychiatrist when a patient has a high BS-POP score; a multidisciplinary approach is also considered wise47).

3. Psychotherapeutic approach

(1) Patient-clinician relationship and clinician's attitude

Patient-clinician relationship, particularly rapport building, plays an important role in treatment outcomes in patients with chronic pain49). A recent review implied that the placebo effect can be enhanced by patient-clinician relationship50). Patient satisfaction is positively associated with affiliative behaviors, such as forward-leaning posture, smiling, nodding, and a relatively high-pitched vocal tone, and negatively associated with physician control51). Patient-centered support, including psychological support, promotion of patient's health literacy, and empowerment of patients to cooperate in finding the correct treatment, can increase the resilience of patient with chronic pain52). Clinicians' empathy has an important role to influence outcome in patients with chronic pain53). An experimental study showed that participants who stated feeling more trust toward their clinician reported less pain in response to painful stimuli54), suggesting that trustworthiness can be an important factor to positive outcomes in patients with chronic pain55).

(2) Reassurance

Reassurance is the removal of fears and concerns in patients with illness. Many guidelines advice the delivery of reassurance to patients with non-specific pain, including LBP56,57). The concept of reassurance aligns with the fear-avoidance model: excessive worry for pain leads patients into a vicious circle of chronic pain58). Pincus et al. proposed a theoretical model of reassurance comprising affective and cognitive components59). Affective reassurance aims to build patient-clinician relationship, which is associated, at best, with improved short-term outcomes, and at worst, with poorer outcomes. By contrast, cognitive reassurance aims to improve the patient's knowledge and understanding of their health problem for reducing their worries, which can improve outcomes in both the short and long term59).

(3) Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

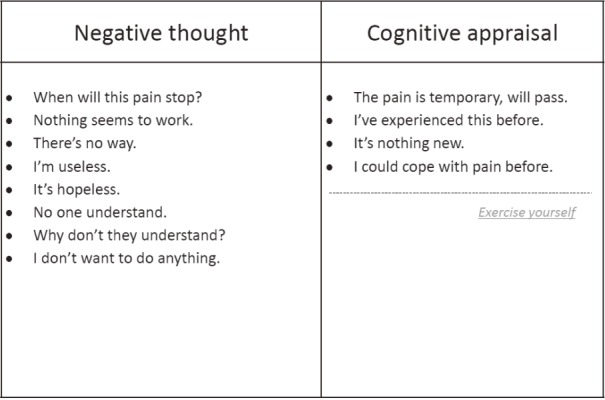

CBT, a form of psychological therapy, has been widely utilized in the treatment of chronic LBP60). In recent trend of behavioral medicine intervention, CBT has been recognized as a second-generation behavioral therapy61). According to a recent systematic review, CBT significantly improves disability and pain catastrophizing in patients with chronic pain after treatment and at follow-up62). As negative and catastrophic thoughts are highly correlated to pain complaints63), CBT focuses on restructuring the negative cognition of the patient into a realistic appraisal. When a realistic appraisal can be gained, the patient may be able to cope with their pain. For example, in patients with chronic LBP with unidentified pathologies, a patient's negative thought of “Pain lasts for several months, but no treatment works for me, and so I feel awful” can be replaced by “I had many experiences of this kind of pain, but my body has been working well and I could get through every time” (Fig. 1). However, these educational suggestions should be provided by skilled practitioners with abundant CBT experience. Otherwise, an insufficient technique may cause a broken relationship between the patient and the clinician. Meanwhile, homework assignments between therapy sessions are an essential component of CBT. Homework should start with easy items at the first stage to build up confidence. Otherwise, patients may be discouraged and would not participate in further therapy64).

Figure 1.

Challenging ways to think about pain.

(4) Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and mindfulness

A third-generation behavior therapy is called acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)61) and is used increasingly for treating chronic pain65). ACT focuses in particular on the concepts of acceptance, and mindfulness. The general understanding of mindfulness meditation or mindfulness interventions is represented by the following: “close your eyes for about a minute and maintain an open awareness of the sensations of breathing at your nostrils. There is no need to do anything special, just continuously observe the sensations of breathing in and breathing out at the nostrils with curiosity and interest”66). Mindfulness has been associated with a small effect of improved pain symptoms compared with control treatment for chronic pain in a meta-analysis of 30 randomized controlled trials; however, there was substantial heterogeneity among these studies67). Moreover, although there are plenty of papers addressing the effect of mindfulness on chronic LBP, its efficacy on pain-related outcomes has not been conclusive; there is limited evidence that it can improve pain acceptance68). Mindfulness intervention may be similar to pain desensitization, as meditation exposes subjects to painful sensations by removing catastrophic thoughts. As a consequence, repeated practice can enhance tolerance for negative emotions69). A current neuroimaging study has indicated that specific brain regions, such as the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex, are involved in the self-referential process during meditation70).

(5) Encouragement of self-management

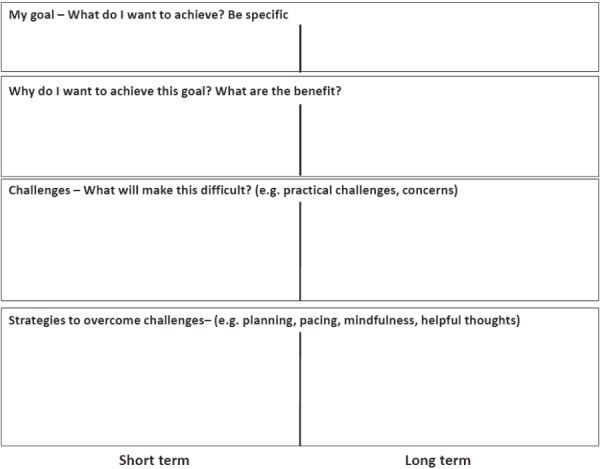

Self-management is considered an important strategy for patients with chronic illness69). In terms of chronic pain, a number of pain intervention programs based on this concept have consistently shown improvements in treatment outcomes72). Confidence in ability to perform specified activities (or self-efficacy belief) has been correlated with the subsequent performance of those activities in patients with chronic LBP73). A well-established self-management program for chronic pain, called ADAPT program74), proposed appropriate “goal setting” and “pacing,” adding to the above strategies, to make the program achievable. In goal setting, patients need to identify what they achieve in their life, and what changes are important to them. The goal should be divided into short- and long-term goals, and they must be realistic, achievable, relevant, and specific (Fig. 2). In addition, when the pain is less, patients are more active, but when the pain is worse, they do less and rest more. The main problem is that they will do less and less. For appropriate pacing, activity should be increased stepwise based on planned targets and not the degree of pain. Simultaneously, other strategies mentioned above help the patient get through and build the confidence to cope with pain.

Figure 2.

Goal setting over 1-week and 3-month periods.

Discussion

Negative perception to self-behavior could be associated with mortality75). It is proposed that physiological pain with organic insult can have negative effects on emotions and cognitive function, and conversely, a negative emotional state can lead to increased pain through the central pain pathway (e.g., noxious neuronal signal to the anterior cingulate cortex)76). Many chronic low back pain have both organic and psychological factors77). Therefore, people with chronic pain usually suffer from not only pain but also overlapping problems, such as depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, working with disabilities, drug overuse, and low quality of life78-80). Thus, biopsychosocial treatment, which can be substituted by a multidisciplinary approach, is becoming an essential strategy for treating chronic pain81). A multidisciplinary approach is commonly a well-organized program that consists of the psychological strategies mentioned above, based on the opinion that none of all approaches to the treatment of chronic pain has a stronger evidence basis for efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and lack of iatrogenic complications than multidisciplinary approach81).

The aim of the present updated review is to introduce the psychological key concepts to clinical practitioners. Indeed, multidisciplinary approaches have succeeded in yielding improvements to pain-related outcomes in patients with chronic pain in Japan, most of which were LBP82-85). However, regardless of the essential relationship between psychological factors and chronic LBP86), there are few facilities that provide a multidisciplinary approach on chronic pain in Japan.

Several reasons might explain why this issue remains unresolved in Japan. First, the psychologist cannot play a role of clinician in Japanese medical administration and insurance system. Although psychotherapeutic treatment by a psychologist needs the instruction of a psychiatrist, most psychiatrists seldom have an interest to treat patients with chronic LBP, and they prefer pharmacotherapy over psychotherapy. Second, in addition to the non-independence of the psychologist, psychotherapeutic studies as medical intervention have lagged behind those in Western countries. In fact, Ono et al. recently reported that while CBT for depression, anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and personality disorder has been studied, randomized control studies of psychotherapy are seldom conducted in Japan87). Indeed, the present review did not find psychotherapeutic studies for chronic pain. It was only in 2014 when a research group at the Japanese Agency for Medical Research and Development in Japan began to establish evidence for the efficacy of CBT on chronic pain in the country88). Third, although most patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain in Japan are initially treated at orthopedic facilities89), educational categories for specialists approved by the Japanese Orthopaedic Association consist of basic science, musculoskeletal diseases based on morphological pathologies, rehabilitation, and medical ethics and safety. They do not include pain education, particularly psychological strategies, indicating that standard techniques in the management of chronic pain are poorly shared among orthopedic physicians. On the other hand, we have to consider limitations of the psychotherapeutic approaches. Although CBT and mindfulness are very useful strategies for treating chronic pain, they should be avoided to prevent form organic insults along with a disease progression when treatable pathophysiologies remain as causes of chronic pain. Therefore, an updated biomedical knowledge is also required in the psychotherapeutic approaches for chronic LBP.

As these strategies can apply to older people with chronic pain90,91), widespread dissemination would be expected for Japan's aging society.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that there are no relevant conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions: All authors have substantially contributed to this review article including concept, collection of references, and preparation of manuscript.

All authors have approved the final version to be published in Spine Surgery and Related Research.

References

- 1.Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin CW, et al. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(12):2075-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liao ZT, Pan YF, Huang JL, et al. An epidemiological survey of low back pain and axial spondyloarthritis in a Chinese Han population. Scand J Rheumatol. 2009;38(6):455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loisel P, Lemaire J, Poitras S, et al. Cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analysis of a disability prevention model for back pain management: a six year follow up study. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59(12):807-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melloh M, Röder C, Elfering A, et al. Differences across health care systems in outcome and cost-utility of surgical and conservative treatment of chronic low back pain: a study protocol. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalichman L, Kim DH, Li L, et al. Computed tomography-evaluated features of spinal degeneration: prevalence, intercorrelation, and association with self-reported low back pain. Spine J. 2010;10(3):200-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inoue S, Kamiya M, Nishihara M, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and burden of failed back surgery syndrome: the influence of various residual symptoms on patient satisfaction and quality of life as assessed by a nationwide Internet survey in Japan. J Pain Res. 2017;10:811-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsudaira K, Kawaguchi M, Isomura T, et al. Assessment of psychosocial risk factors for the development of non-specific chronic disabling low back pain in Japanese workers-findings from the Japan Epidemiological Research of Occupation-related Back Pain (JOB) study. Ind Health. 2015;53(4):368-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kikuchi S. New concept for backache: biopsychosocial pain syndrome. Eur Spine J. 2008;17 Suppl 4:421-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kikuchi S. The Recent Trend in Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain. Spine Surg Relat Res. 2017;1(1):1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Sep 2;(9):CD000963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brox JI, Reikerås O, Nygaard Ø, et al. Lumbar instrumented fusion compared with cognitive intervention and exercises in patients with chronic back pain after previous surgery for disc herniation: a prospective randomized controlled study. Pain. 2006;122(1-2):145-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikemoto T, Arai YC, Nishihara M, et al. Strategies for managing chronic pain: Case of a skilled orthopaedic physician and mini-review. Open J Orthop. 2015;5:109-14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norman G. Dual processing and diagnostic errors. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009;14 Suppl 1:37-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panda A, Das CJ, Baruah U. Imaging of vertebral fractures. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18(3):295-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karunanayake AL, Pathmeswaran A, Wijayaratne LS. Chronic low back pain and its association with lumbar vertebrae and intervertebral disc changes in adults. A case control study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21(3):602-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Allen RR, et al. Core outcome domains for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2003;106(3):337-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of low-back pain. Part II: development of guidelines for trials of treatment in primary care. Spine. 1983 Mar;8(2):145-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzukamo Y, Fukuhara S, Kikuchi S, et al.; Committee on Science Project, Japanese Orthopaedic Association. Validation of the Japanese version of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8(4):543-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, et al. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980 Aug;66(8):271-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujiwara A, Kobayashi N, Saiki K, et al. Association of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association score with the Oswestry Disability Index, Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, and short-form 36. Spine. 2003;28(14):1601-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamashiro K, Arimura T, Iwaki R, et al. A multidimensional measure of pain interference: Reliability and validity of the pain disability assessment scale. Clin J Pain 2011;27(4):338-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arimura T, Komiyama H, Hosoi M. Pain disability assessment scale: a simplified scale for clinical use. Jpn J BehavTher 1997;23:7-15. (in Japanease) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendall NAS, Linton SJ, Main CJ. Guide to assessing psychosocial yellow flags in acute low back pain: Risk factors for long-term disability and work loss. Wellington, NZ: ACC; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linton SJ, Boersma KMA. Early identification of patients at risk of developing a persistent back problem: The predictive validity of The Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:80-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, et al. A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine. 2002;27:E109-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westman A, Linton SJ, Ohrvik J, et al. Do psychosocial factors predict disability and health at a 3-year follow-up for patients with non-acute musculoskeletal pain? A validation of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Eur J Pain. 2008;12(5):641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takasaki H, Gabel CP. Cross-cultural adaptation of the 12-item Örebro musculoskeletal screening questionnaire to Japanese (ÖMSQ-12-J), reliability and clinicians' impressions for practicality. J Phys Ther Sci. 2017;29(8):1409-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabel CP, Burkett B, Melloh M. The shortened Örebro Musculoskeletal Screening Questionnaire: evaluation in a work-injured population. Man Ther. 2013;18(5):378-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gabel CP, Melloh M, Burkett B, et al. The Örebro Musculoskeletal Screening Questionnaire: validation of a modified primary care musculoskeletal screening tool in an acute work injured population. Man Ther. 2012;17(6):554-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill JC, Dunn KM, Main CJ, et al. Subgrouping low back pain: a comparison of the STarT Back Tool with the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:83-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M, et al. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9802):1560-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsudaira K, Oka H, Kikuchi N, et al. Psychometric Properties of the Japanese Version of the STarT Back Tool in Patients with Low Back Pain. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0152019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsudaira K, Kikuchi N, Kawaguchi M, et al. Development of a Japanese version of the STarT (Subgrouping for Targeted Treatment) Back screening tool: translation and linguistic validation. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain Research. 2013;5:11-9. (Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsudaira K, Oka H, Kikuchi N, et al. The Japanese version of the STarT Back Tool predicts 6-month clinical outcomes of low back pain. J Orthop Sci. 2017;22(2):224-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foster NE, Mullis R, Hill JC, et al. IMPaCT Back Study team. Effect of stratified care for low back pain in family practice (IMPaCT Back): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):102-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between pain catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain 2001;17:52-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asghari A, Nicholas MK. Personality and pain-related beliefs/coping strategies: a prospective study. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(1):10-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sullivan MJL, Adams H, Horan S, et al. The role of perceived injustice in the experience of chronic pain and disability: Scale development and validation. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18(3):249-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sullivan MJ. What is the clinical value of assessing pain-related psychosocial risk factors? Pain Manag. 2013;3(6):413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan MJL, Bishop S, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess 1995;7:432-524. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: Taking pain into account. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(2):153-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iwaki R, Arimura T, Jensen MP, et al. Global catastrophizing vs catastrophizing subdomains: assessment and associations with patient functioning. Pain Med. 2012;13(5):677-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuoka H, Sakano Y. Assessment of cognitive aspect of pain: Development, reliability, and validation of Japanese version of Pain Catastrophizing Scale. Jpn J Psychosom Med 2007;47:95-102. (Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adachi T, Nakae A, Maruo T, et al. Validation of the Japanese version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire in Japanese patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2014;15(8):1405-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamada K, Adachi T, Mibu A, et al. Injustice Experience Questionnaire, Japanese Version: Cross-Cultural Factor-Structure Comparison and Demographics Associated with Perceived Injustice. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0160567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, et al. A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine. 2002;27(5):E109-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watanabe K, Kikuchi S, Konno S, et al. Brief scale for psychiatric problems in orthopaedic patients (BS-POP) validation study. Rinshou Seikeigeka (Clin Orthop Surg). 2005;40:745-51 (Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshida K, Sekiguchi M, Otani K, et al. A validation study of the Brief Scale for Psychiatric problems in Orthopaedic Patients (BS-POP) for patients with chronic low back pain (verification of reliability, validity, and reproducibility). J Orthop Sci. 2011;16(1):7-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bieber C, Müller KG, Blumenstiel K, et al. Long-term effects of a shared decision-making intervention on physician-patient interaction and outcome in fibromyalgia. A qualitative and quantitative 1 year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63(3):357-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benedetti F. Placebo and the new physiology of the doctor-patient relationship. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(3):1207-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kiesler DJ, Auerbach SM. Integrating measurement of control and affiliation in studies of physician-patient interaction: the interpersonal circumplex. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(9):1707-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Náfrádi L, Kostova Z, Nakamoto K, et al. The doctor-patient relationship and patient resilience in chronic pain: A qualitative approach to patients' perspectives. Chronic Illn. 2017 Jan 1:1742395317739961. doi: 10.1177/1742395317739961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cánovas L, Carrascosa AJ, García M, et al. Empathy Study Group. Impact of Empathy in the Patient-Doctor Relationship on Chronic Pain Relief and Quality of Life: A Prospective Study in Spanish Pain Clinics. Pain Med. 2018;19(7):1304-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Losin EAR, Anderson SR, Wager TD. Feelings of Clinician-Patient Similarity and Trust Influence Pain: Evidence From Simulated Clinical Interactions. J Pain. 2017 Jul;18(7):787-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ashton-James CE, Nicholas MK. Appearance of trustworthiness: an implicit source of bias in judgments of patients' pain. Pain. 2016;157(8):1583-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, et al. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;15 Suppl 2:S192-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Evidence-based management of acute musculoskeletal pain. Ageing Commonwealth Department of Health a d Aging (CDoHa). Brisbane: Australian Academic Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain. 2000;85(3):317-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pincus T, Holt N, Vogel S, et al. Cognitive and affective reassurance and patient outcomes in primary care: a systematic review. Pain. 2013;154(11):2407-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):153-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hayes SC. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Relational Frame Theory, and the Third Wave of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies - Republished Article. Behav Ther. 2016;47(6):869-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Williams AC, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Nov 14;11:CD007407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Affleck G, Urrows S, Tennen H, et al. Daily coping with pain from rheumatoid arthritis: patterns and correlates. Pain. 1992;51:221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Songer D. Psychotherapeutic Approaches in the Treatment of Pain. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(5):19-24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wetherell JL, Afari N, Rutledge T, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain. 2011;152(9):2098-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Creswell JD. Mindfulness Interventions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2017;68:491-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51:199-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cramer H, Haller H, Lauche R, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for low back pain. A systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract. 2003;10(2):125-43. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Moran JM, Nieto-Castañón A, et al. Associations and dissociations between default and self-reference networks in the human brain. Neuroimage. 2011;55(1):225-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mann EG, Lefort S, Vandenkerkhof EG. Self-management interventions for chronic pain. Pain Manag. 2013;3(3):211-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Council JR, Ahern DK, Follick MJ, et al. Expectancies and functional impairment in chronic low back pain. Pain. 1988;33(3):323-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nicholas MK, Molloy AM, Tokin L, et al. Manage Your Pain 3rd edition: Practical and Positive Ways of Adapting to Chronic Pain. ABC books. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zahrt OH, Crum AJ. Perceived physical activity and mortality: Evidence from three nationally representative U.S. samples. Health Psychol. 2017;36(11):1017-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bushnell MC, Ceko M, Low LA. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:502-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2356-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(4):287-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nakamura M, Nishiwaki Y, Ushida T, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic musculoskeletal pain in Japan. J Orthop Sci. 2011;16(4):424-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Inoue S, Kobayashi F, Nishihara M, et al. Chronic Pain in the Japanese Community--Prevalence, Characteristics and Impact on Quality of Life. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.IASP Clinical Updates. Interdisciplinary Chronic Pain Management: International Perspectives. 2012;20(7):1-5. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hayashi K, Arai YC, Ikemoto T, et al. Predictive factors for the outcome of multidisciplinary treatments in chronic low back pain at the first multidisciplinary pain center of Japan. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(9):2901-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Inoue M, Inoue S, Ikemoto T, et al. The efficacy of a multidisciplinary group program for patients with refractory chronic pain. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(6):302-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tetsunaga T, Tetsunaga T, Nishida K, et al. Short-term outcomes of patients being treated for chronic intractable pain at a liaison clinic and exacerbating factors of prolonged pain after treatment. J Orthop Sci. 2017;22(3):554-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Inoue M, Ikemoto T, Inoue S, et al. Analysis of follow-up data from an outpatient pain management program for refractory chronic pain. J Orthop Sci. 2017;22(6):1132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Linton SJ. A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine. 2000;25(9):1148-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ono Y, Furukawa TA, Shimizu E, et al. Current status of research on cognitive therapy/cognitive behavior therapy in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65(2):121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shibata M. Research project for spread and efficacy of cognitive behavioral Therapy for chronic pain. 2017;16ek0610004h003 (Japanese). https://www.amed.go.jp/content/files/jp/houkoku_h28/0105020/h26_002.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2018

- 89.Nakamura M, Nishiwaki Y, Ushida T, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic musculoskeletal pain in Japan: a second survey of people with or without chronic pain. J Orthop Sci. 2014;19(2):339-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nicholas MK, Asghari A, Blyth FM, et al. Self-management intervention for chronic pain in older adults: a randomised controlled trial. Pain. 2013;154(6):824-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nicholas MK, Asghari A, Blyth FM, et al. Long-term outcomes from training in self-management of chronic pain in an elderly population: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2017;158(1):86-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]