Abstract

Introduction

Few studies have investigated the influence of cage subsidence patterns (intraoperative endplate injury or late-onset cage settling) on bony fusion and clinical outcomes in lateral interbody fusion (LIF). This retrospective study was performed to compare the fusion rate and clinical outcomes of cage subsidence patterns in LIF at one year after surgery.

Methods

Participants included 93 patients (aged 69.0±0.8 years; 184 segments) who underwent LIF with bilateral pedicle screw fixation. All segments were evaluated by computed tomography and classified into three groups: Segment E (intraoperative endplate injury, identified immediately postoperatively); Segment S (late-onset settling, identified at 3 months or later); or Segment N (no subsidence). We compared patient characteristics, surgical parameters and fusion status at 1 year for the three subsidence groups. Patients were classified into four groups: Group E (at least one Segment E), Group S (at least one Segment S), Group ES (both Segments E and S), or Group N (Segment N alone). Visual analog scales (VASs) and the Japanese Orthopedic Association Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire (JOABPEQ) were compared for the four patient groups.

Results

184 segments were classified: 31 as Segment E (16.8%), 21 as Segment S (11.4%), and 132 as Segment N (71.7%). Segment E demonstrated significantly lower bone mineral density (-1.7 SD of T-score, p=0.003). Segment S demonstrated a significantly higher rate of polyetheretherketone (PEEK) cages (100%, p=0.03) and a significantly lower fusion rate (23.8%, p=0.01). There were no significant differences in VAS or in any of the JOABPEQ domains among the four patient groups.

Conclusions

Intraoperative endplate injury was significantly related to bone quality, and late-onset settling was related to PEEK cages. Late-onset settling demonstrated a worse fusion rate. However, there were no significant differences in clinical outcomes among the subsidence patterns.

Keywords: lateral interbody fusion, cage subsidence, endplate injury, late-onset settling, CT-MPR; computed tomography multiplanar reconstruction, JOABPEQ; Japanese Orthopedic Association Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire

Introduction

An advantage of the lateral interbody fusion (LIF) procedure is restoration of the impaired disc height through the insertion of a large footprint cage, without compromising the posterior elements in various spinal deformities or degenerative cases. This procedure achieves better local alignment and indirect decompression of neural elements. However, these effects may be spoiled by cage subsidence into the adjacent vertebral endplate. Cage subsidence is therefore considered a serious complication of LIF.

Several reports have described postoperative cage subsidence in LIF series, with an incidence of 0.3%-22%1-3). Many reports have mixed two types of cage subsidence, one results from intraoperative endplate injury and the other (late-onset settling) occurs gradually over the postoperative course. The etiology of these two types of cage subsidence should be considered separately. The former is an iatrogenic endplate violation during the endplate preparation or cage insertion procedures. The latter is a spontaneous reaction between the cage and endplate. Few studies have investigated the correlating factors or clinical outcomes of each type of LIF cage subsidence separately.

We reviewed 93 consecutive patients who underwent LIF with 18-mm (width) cages and supplemental bilateral pedicle screws. In this series, we investigated cage subsidence for postoperative 1 year. This study was designed to analyze the factors correlated with each type of subsidence and compare the fusion rate and clinical outcomes between subsidence patterns.

Materials and Methods

Patient population

We conducted our retrospective review using a prospective cohort. The study included consecutive patients who underwent LIF at a single institute from February 2013 to February 2015. In total, 93 patients (aged 69.0 ± 0.8 years; 34 males; total 184 segments) who underwent LIF with a transpsoas approach in a minimally invasive fashion (XLIF; NuVasive Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) were enrolled in this study. Diagnoses were degenerative scoliosis/kyphoscoliosis (n=38), spondylolisthesis (n=27), adjacent segmental disease (n=11), stenosis (n=7), and other (n=10).

Surgical technique

The operations were performed by six surgeons; however, all cases were under the supervision of one of the senior authors. Procedures strictly followed the surgical technique described by Ozgur et al.4). For endplate preparation, surface marking with soft indentation made by a box cutter was followed by annular incision with a knife. After removal of the disc material with a rongeur, a Cobb elevator was advanced gently under fluoroscopy guidance along the endplates to release the contralateral annulus. Cage size trials were followed by additional disc curettage and rasping of the endplates. A box cutter was not used routinely for disc removal, but only for younger patients with a larger disc height (more than 11 mm). All cages were inserted using two containment sliders to protect the endplates and to keep graft material inside the cage. For the first 14 patients (27 segments), titanium cages of a standard 18-mm width (CoRoent XL; NuVasive Inc. San Diego, CA, USA) were used. Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) cages of the same width were used for all remaining patients. For graft material, the last six patients (14 segments) received artificial bone material comprising hydroxyapatite and collagen (Refit; HOYA Technosurgical, Tokyo, Japan) soaked in autologous bone marrow aspirate. The other patients (n=87, 170 segments) received allograft bone harvested from the femoral head. All LIF segments were supplemented with bilateral pedicle screw fixation.

Data collection

Patient demographic and surgical details were obtained from clinical charts. Age at surgery; sex; history of smoking; T-score for bone mineral density (BMD) measured at the left femoral neck using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; diagnosis; surgical site; cage height (8-14 mm), length (40-60 mm) and angle (0° or -10°); and graft materials were investigated (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics.

| Characteristics | Patients (n=93) |

| Age (years) | 69.0±0.8 |

| Sex | Male 34 |

| Female 59 | |

| Smoking (Yes) | 14 (15.1%) |

| BMD (T-score) | -0.93±0.11 |

| Diagnosis | Degenerative scoliosis/kyphoscoliosis: 38 (20.7%) |

| Spondylolisthesis: 27 (14.7%) | |

| Adjacent segmental disease: 11 (6.0%) | |

| Stenosis: 7 (3.8%) | |

| Others: 10 (5.4%) | |

| Surgical details | Segments (n=184) |

| Surgical site | Thoracic spine: 17 (9.2%) |

| Upper lumbar spine (L1-L2, L2-L3): 46 (25.5%) | |

| Lower lumber spine (L3-L4, L4-L5): 120 (65.2%) | |

| Cage material | Ti: 27 |

| PEEK: 157 | |

| Cage height (mm) | 9.7±0.1 |

| Cage length (mm) | 49.0±0.4 |

| Cage angle | 0°: 22 |

| -10°: 162 | |

| Graft materials | Allograft bone: 170 |

| Artificial bone+bone marrow aspire: 14 |

n=number of patients or segments.

Continuous numbers are shown as mean±standard error.

Categorical variables are shown as total number.

BMD, bone mineral density; Ti, titanium; PEEK, polyetheretherketone.

Radiographic examination

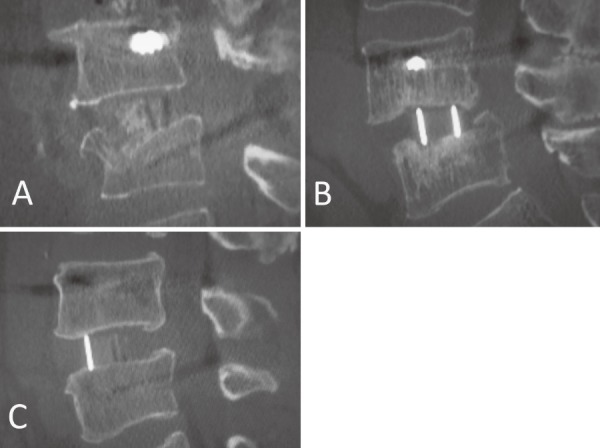

Radiographic assessment was performed using computed tomography multiplanar reconstruction (CT-MPR) through the cages in contiguous 1-mm slices. Evaluation was performed by two independent spinal surgeons who were blinded to the study information two times respectively. Intra- and interobserver variances were assessed by calculating κ values. A third reviewer was available for adjudication in cases of disagreement. CT-MPR was performed at five time points: preoperatively, immediately after surgery (within 5 days), and postoperatively at 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year. CT-MPR radiation exposure at the lumbar spine was estimated at 9.9-12.6 mSv each time, according to simulation software CT-Expo version 2.0 (SASCRAD; Buchholz, Germany). The sagittal planes of each segment were evaluated, and subsidence was defined as a cage sinking more than 2 mm into the adjacent vertebral endplate. The site of the subsidence (anterior [SA] or posterior [SP] corner of the cage in the superior endplate of the caudal vertebra, anterior [IA] or posterior [IP] corner of inferior endplate of the rostral vertebra) was also investigated. For degenerative scoliosis patients, the laterality of the subsidence (concave, convex, or bilateral side) and the osteophyte formation of each segment were investigated as well. Subsidence identified at the immediately postoperative CT-MPR was classified as intraoperative endplate injury (Segment E, Fig. 1A). Subsidence identified at 3 months or later was classified as late-onset settling (Segment S, Fig. 1B). Segments that demonstrated no subsidence throughout the study period were classified as no subsidence (Segment N, Fig. 1C). Obvious progression of subsidence from the initial sinking place (more than 2 mm) until postoperative 1 year was evaluated. At postoperative 1 year, a segment that demonstrated bridging bone formation in the coronal or sagittal plane in two consecutive slices was defined as fusion. The fusion rate at postoperative 1 year and the rate of subsidence progression over 2 mm were compared among the three subsidence groups. From the preoperative CT-MPR, each disc height at endplate's center of the anterior-posterior border of the vertebra was measured. Based on this measurement, the disc height gap was calculated as: cage height- preoperative disc height (mm).

Figure 1.

Subsidence groups. A, Intraoperative endplate injury (Segment E). B, Late-onset settling (Segment S). C, No subsidence (Segment N).

Clinical outcomes

Overall, 85 patients (91.4%) completed visual analog scales (VASs) for low back pain, leg pain, and leg numbness preoperatively and at postoperative 1 year. Participants also completed the self-administered Japanese Orthopedic Association Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire (JOABPEQ). JOABPEQ comprises 25 questions across five domains: pain-related disorders, lumbar spine dysfunction, gait disturbance, social life dysfunction, and psychological disorders. For each domain, the difference between preoperative scores and those at postoperative 1 year (improvement score) was calculated and the effectiveness of the treatment evaluated5).

According to the subsidence pattern of each segment, the 85 patients were classified as follows: Group E (at least one Segment E), Group S (at least one Segment S), Group ES (both Segments E and S), or Group N (Segment N alone). We compared the VAS scores and the improvement scores for the five JOABPEQ domains among the four patient groups.

Statistical analyses

Patient demographics, surgical details, and radiographic measurement parameters were compared among the three subsidence groups (Segments E, S, and N). VAS scores and improvement scores for the five JOABPEQ domains were compared among the four patient groups (Groups E, S, ES, and N). One-way analysis of variance was used for continuous variables. A post-hoc analysis for multiple comparisons was performed using the Bonferroni correction. Chi square tests were used for dichotomous and categorical variables. A p-value <0.05 was accepted as significant. For the significant continuous variable, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to determine the cutoff value. All analyses were performed using SPSS Version 22 software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp.).

Results

Radiological outcomes

Table 2 summarizes the comparison of demographic and radiological factors among the three subsidence groups. The κ values for intra- and interobserver reliability for the classification of cage subsidence were 0.87 and 0.76 respectively. Total postoperative cage subsidence was identified in 52 segments (28.3%) in 34 patients until postoperative 1 year. These consisted of 31 intraoperative endplate injury segments (Segment E, 16.8%) and 21 late-onset settling segments (Segment S, 11.4%). The majority of Segment E (28 segments, 90.3%) was located at SA. On the other hand, only half (10 segments, 47.6%) of Segment S was located at SA, with the remaining segments (nine segments, 42.9%) also involving the inferior endplate of the rostral vertebra. This difference in subsidence site was statistically significant (p=0.04).

Table 2.

Comparison of Patient Demographics and Surgical Details among the Three Subsidence Groups.

| Segment E (n=31) | Segment S (n=21) | Segment N (n=132) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsidence site | SA: 28

SP: 1 IA: 1 IP: 1 |

SA: 10

SP: 1 IA: 1 IP: 0 SA+SP: 1 IA+IP: 2 SA+IA+IP: 1 SA+SP+IA: 1 SP+IP: 2 SA+SP+IA+IP: 2 |

None | 0.04 |

| Age (years) | 68.1±2.3 | 68.7±2.9 | 69.3±0.9 | 0.98 |

| Sex | M: 1

F: 30 |

M: 11

F: 10 |

M: 45

F: 87 |

0.07 |

| Smoking (Yes) | 3 (9.7%) | 1 (4.8%) | 18 (13.6%) | 0.46 |

| BMD (T-score) | -1.7±0.2 | -0.3±0.5 | -0.8±0.1 | 0.003 |

| Diagnosis | Degenerative scoliosis/kyphoscoliosis: 21 (67.7%)

Spondylolisthesis: 7 (22.6%) Adjacent segmental disease: 1 (3.2%) Stenosis: 0 (0%) Others: 2 (6.5%) |

Degenerative scoliosis/kyphoscoliosis: 12 (57.1%)

Spondylolisthesis: 5 (23.8%) Adjacent segmental disease: 2 (9.5%) Stenosis: 0 (0%) Others: 2 (9.5%) |

Degenerative scoliosis/kyphoscoliosis: 76 (57.6%)

Spondylolisthesis: 24 (18.2%) Adjacent segmental disease: 14 (10.6%) Stenosis: 7 (5.3%) Others: 11 (8.3%) |

0.72 |

| Surgical site | T: 4

UL: 12 LL: 15 |

T: 3

UL: 7 LL: 11 |

T: 10

UL: 27 LL: 95 |

0.09 |

| Cage material | Ti: 2

PEEK: 29 |

Ti: 0

PEEK: 21 |

Ti: 25

PEEK: 107 |

0.03 |

| Cage height (mm) | 10.1±0.2 | 9.1±0.3 | 9.7±0.1 | 0.08 |

| Cage length (mm) | 47.8±0.8 | 48.5±1.5 | 49.4±0.4 | 0.29 |

| Cage angle | 0°: 2

-10°: 29 |

0°: 2

-10°: 19 |

0°: 18

-10°: 114 |

0.51 |

| Disc height gap (mm) | 4.0±0.3 | 3.7±0.4 | 4.4±0.2 | 0.4 |

| Graft material | Allograft: 27

Artificial bone material and bone marrow aspire: 4 |

Allograft: 18

Artificial bone material and bone marrow aspire: 3 |

Allograft: 125

Artificial bone material and bone marrow aspire: 7 |

0.64 |

n=number of segments.

Continuous numbers are shown as mean±standard error.

Categorical variables are shown as total number.

SA, anterior corner of the superior endplate of the caudal vertebra; SP, posterior corner of the superior endplate of the caudal vertebra; IA, anterior corner of the inferior endplate of the rostral vertebra; IP, posterior corner of the inferior endplate of the rostral vertebra; M, male; F, female; BMD, bone mineral density; T, thoracic spine; UL, upper lumbar spine (L1-L2, L2-L3); LL, lower lumbar spine (L3-L4, L4-L5); Ti, titanium; PEEK, polyetheretherketone. Disc height gap, cage height - preoperative disc height (mm)

In degenerative scoliosis patients (109 segments), cage subsidence was identified in 33 segments (30.3%). Five (15.2%) were in concave, 3 (9.1%) were in convex, and 25 (75.8%) were in bilateral sides. All eight segments found in concave or convex side were classified into Segment E. Nineteen (57.6%) were found in the side with osteophyte formation. There was no significant correlation between the laterality of cage subsidence and the osteophyte formation.

In Segment E, the BMD was significantly lower (p=0.003) and the ratio of females to males tended to be higher (p=0.07) than those in the other two groups. ROC curve analysis revealed that cutoff value of BMD for the best prediction of intraoperative endplate injury was -1.0 SD of the T-score, with a sensitivity of 83.9% and specificity of 58.3%.

Segments S included no titanium cages, giving a significantly higher proportion of PEEK cages than those in the other two groups (p=0.03). There was no significant difference among the subsidence groups in cage height, length, angle, the disc height gap, or graft material.

In terms of the progression over 2 mm during the study period, eight segments (4.3%) were found to progress in 1 year (Table 3); five in Segment E (16.1%) and three in Segment S (14.3%). The incidence of subsidence progression did not significantly differ between the groups (p=0.98).

Table 3.

Subsidence Progression and Fusion at One Year after Surgery, by Subsidence Group.

| Segment E (n=31) | Segment S (n=21) | Segment N (n=132) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsidence progression (>2 mm) |

5 (16.1%) | 3 (14.3%) | 0 ( 0%) | 0.98 |

| Fusion | 11 (35.5%) | 5 (23.8%) | 72 (54.5%) | 0.01 |

n=number of segments.

Categorical variables are shown as total number.

The fusion rate confirmed by CT-MPR at postoperative 1 year was 35.5% in Segment E, 23.8% in Segment S, and 54.5% in Segment N. Segment S demonstrated a significantly lower fusion rate than those in the other two groups (p=0.01); however, the difference between Segments E and N was not statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 4 shows the comparison of the subsidence segments with progression (>2 mm) (n=8) and those without progression (n=44) at postoperative 1 year. Although progression was observed relatively more often in the lower lumbar spine, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of patient demographic and surgical details.

Table 4.

Comparison of the Subsidence Segments with Progression (>2 mm) and without Progression at Postoperative 1 Year.

| With progression (n=8) |

Without progression (n=44) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.6±3.5 | 68.1±2.0 | 0.76 |

| Sex | M: 2 F: 8 |

M: 10 F: 34 |

0.6 |

| Smoking (Yes) | 0 (0%) | 4 (9.1%) | 0.5 |

| BMD (T-score) | -1.0±0.4 | -1.2±0.3 | 0.82 |

| Diagnosis | Degenerative scoliosis/kyphoscoliosis: 4 (50%) Spondylolisthesis: 4 (50%) Adjacent segmental disease: 0 (0%) Stenosis: 0 (0%) Others: 0 (0%) |

Degenerative scoliosis/kyphoscoliosis: 29 (65.9%) Spondylolisthesis: 8 (18.2%) Adjacent segmental disease: 3 (6.8%) Stenosis: 0 (0%) Others: 4 (9.1%) |

0.21 |

| Surgical site | T: 0 UL: 2 LL: 6 |

T: 7 UL: 17 LL: 20 |

0.25 |

| Cage height (mm) | 10.3±0.4 | 9.6±0.2 | 0.23 |

| Cage length (mm) | 50.6±1.8 | 47.6±0.9 | 0.18 |

| Cage angle | 0°: 0 -10°: 8 |

0°: 4 -10°: 40 |

0.50 |

| Disc height gap (mm) | 4.4±1.0 | 3.8±0.3 | 0.45 |

| Graft material | Allograft: 6 Artificial bone material and bone marrow aspirate: 2 |

Allograft: 39 Artificial bone material and bone marrow aspirate: 5 |

0.50 |

n=number of segments.

Continuous numbers are shown as mean±standard error.

Categorical variables are shown as total number.

M, male; F, female; BMD, bone mineral density; T, thoracic spine; UL, upper lumbar spine (L1-L2, L2-L3); LL, lower lumbar spine (L3-L4, L4-L5)

Disc height gap, cage height - preoperative disc height (mm)

Clinical outcomes

In the patient group classification based on CT-MPR evaluation, the 85 patients who completed VASs and JOABPEQ were classified into four groups: 19 patients (20.4%) into Group E, 11 patients (11.8%) into Group S, four patients (4.3%) into Group ES, and 51 patients (63.4%) into Group N. Preoperatively and at postoperative 1 year, there were no significant differences in VAS scores or the improvement scores for the five JOABPEQ domains among the four groups (Table 5).

Table 5.

VAS Scores and Improvement Scores for the Five JOABPEQ Domains.

| Patient group | Group E (n=19) | Group S (n=11) | Group ES (n=4) | Group N (n=51) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS Low back pain Preoperative 1 year |

67.5±5.8 38.9±8.8 |

59.0±12.0 36.0±10.4 |

74.0±9.7 45.3±8.4 |

61.9±4.8 26.0±3.6 |

0.78 0.27 |

| VAS Leg pain Preoperative 1 year |

69.7±6.6 27.1±7.5 |

62.8±12.2 33.4±13.1 |

77.8±8.8 56.5±7.4 |

65.4±4.5 30.4±4.5 |

0.82 0.38 |

| VAS Leg numbness Preoperative 1 year |

65.6±8.2 48.7±11.3 |

60.0±11.8 31.3±14.0 |

69.3±11.0 59.3±19.6 |

61.8±4.8 34.5±5.2 |

0.94 0.38 |

| JOABPEQ Pain-related disorders | 27.0±7.8 | 35.9±11.3 | -11.0±15.8 | 34.9±5.9 | 0.13 |

| Lumbar spine dysfunction | -6.6±8.2 | -11.6±12.4 | -21.0±8.0 | 7.7±5.2 | 0.16 |

| Gait disturbance | 18.3±6.5 | 16.1±6.1 | 10.5±4.5 | 37.3±4.7 | 0.24 |

| Social life dysfunction | 15.6±5.8 | 9.1±1.8 | 22.3±9.3 | 21.2±3.1 | 0.26 |

| Psychological disorders | 16.1±5.8 | -1.9±7.7 | 5.0±3.5 | 20.1±3.6 | 0.07 |

| Pain-related disorders | 27.0±7.8 | 35.9±11.3 | -11.0±15.8 | 34.9±5.9 | 0.13 |

n=number of patients.

Values are mean±standard error.

VAS, visual analogue scale.

JOABPEQ, Japanese Orthopedic Association Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire

Discussion

Subsidence is a term used to describe a decrease in the vertical height of the disc space before complete incorporation of the fusion mass6). Lee et al.7) compared the cage subsidence rate of anterior-(ALIF), posterior-(PLIF), and transforaminal-(TLIF) lumbar interbody fusion at two years after surgery. The cage subsidence rate was 15.4% in ALIF, 38.1% in TLIF, and 10% in PLIF. However, no papers directly compared the cage subsidence rate between LIF and TLIF or PLIF.

In terms of cage subsidence patterns in LIF, several studies have reported poorer outcomes for intraoperative endplate injury than for late-onset settling. Tohmeh et al.8) reported that the levels of intraoperative cage settling (endplate injury) demonstrated progressive settling at a greater magnitude than levels without intraoperative cage settling. In addition, clinical improvement at one year after surgery was significantly higher for patients without intraoperative cage settling than for those with intraoperative cage settling. Santoni et al.9) conducted a biomechanical study using a cadaver model of endplate injury in LIF and concluded that segmental stability may be compromised by the injury.

On the other hand, late-onset cage settling is thought to be part of the normal healing process. Choi et al.6) described postoperative cage subsidence in anterior interbody fusion as a normal incorporation process of the cage to achieve better contact with both endplates, which have different surface shapes. Tokuhashi et al.10) analyzed the subsidence of a metal cage after posterior lumbar interbody fusion and reported that the degree of cage subsidence and decrease of disk height were not correlated with the final clinical results.

Malham et al. described two types of cage subsidence in LIF: early cage subsidence and delayed onset subsidence (DCS)11). They analyzed the clinical and radiological outcomes of DCS cases and concluded that DCS did not affect interbody fusion rates or clinical outcomes.

Several factors are reported to cause cage subsidence in intervertebral fusions including LIF: reduced bone quality12,13), older age13), multilevel procedures1,14), narrow cage1,2), and use of rhBMP-215). However, the abovementioned reports mixed two types of cage subsidence (intraoperative injury and postoperative spontaneous settling). In the present study, CT-MPR at an immediately postoperative time point enables the two types of cage subsidence to be distinguished.

Segment E (intraoperative endplate injury) was significantly related to reduced BMD and included a relatively higher number of females who (in this mainly postmenopausal patient population) suffered from osteoporosis. Hou et al.13) showed a lower endplate failure load in vertebrae with lower BMD and concluded that patients with osteoporosis have a higher risk of cage subsidence. They also provided mechanical data proving that the anterior site of the endplate is weaker than the posterior site. Grant et al.16) demonstrated the mechanical weakness of the central region of the endplate using indentation tests. In addition, they showed that the superior endplate was mechanically weaker than the inferior endplate. This biomechanical data supports our findings that endplate injuries were mostly observed at the anterior corner of the cage in the superior endplates of the caudal vertebra.

According to the ROC analysis, patients with T-score less than -1.0 SD should be watched for intraoperative endplate injury. Perioperative treatments for osteoporosis and intraoperative gentle manipulation of endplates are recommended.

Several intraoperative endplate injuries in the unilateral site were observed in degenerative scoliosis cases. This might be due to the nonparallel orientation of the endplates, attributed to surgeon technical failures.

Conversely, late-onset settling was not directly affected by bone quality. Nearly half of the Segment S group (late-onset settling) involved the inferior endplate of the rostral vertebra, which is not the weakest area of the vertebral surface. Rather, late-onset settling was found to correlate with cage material, as all patients in the segment S group received a PEEK cage. According to Vadapalli et al.17), PEEK cages have a modulus of elasticity closely resembling that of cortical bone. They described how PEEK spacers reduce the stresses in the adjacent endplates as well as subsidence, and facilitate bony fusion. However, there are several studies on interbody fusion that have demonstrated contradictory results regarding the superiority of PEEK over titanium as the cage material18,19). PEEK cage teeth are reported to be less sharp than those of titanium cages20). PEEK implants also tend to have a fibrous connective tissue surface interface, probably due to reduced osteoblastic differentiation of progenitor cells and production of an inflammatory environment that favors cell death via apoptosis and necrosis21). Although it is possible that the artifact effect of a titanium cage may camouflage subsidence in CT-MPR, PEEK cages showed a higher rate of late-onset settling.

Both types of cage subsidence showed a similar incidence (approximately 15%) of obvious progression of subsidence and a lower fusion rate at postoperative 1 year, although the fusion rate was significantly lower in late-onset settling. It is still unclear whether this can be attributed to PEEK characteristics or other factors. Steffen et al. reported that large micromotion at the interface between graft and host bone should be avoided to achieve fusion22). Tanida et al. hypothesized that the repetitive local mechanical stress caused by insufficient initial stability between the cage and the endplate may lead to endplate microfracture23).

In this study, all segments were supplemented with bilateral pedicle screws. In cases of intraoperative endplate injury, potential instability might be prevented by additional pedicle screw fixation. On the other hand, late-onset settling is a sign of instability remaining even after pedicle screw fixation. Insufficient stability of the construct and compromise of the endplate might aggravate each other, and result in delayed union or pseudoarthrosis.

However, there were no parameters correlating directly with subsidence progression. Neither bone quality nor spinal pathogenesis affected it. Although progression was likely to be found in the lower lumbar spine, the total number of the segments with subsidence progression was low. Further case accumulation is necessary to clarify the mechanism of subsidence progression.

Clinical outcomes were not affected by either intraoperative endplate injury or late-onset settling at postoperative 1 year. These results are consistent with previous literature10,11). However, a longer follow-up period and larger number of cases are necessary to clarify the influence of cage subsidence on clinical outcomes. In addition, as mentioned above, all segments were supplemented with bilateral pedicle screws. This additional posterior fixation might have minimized the effect of cage subsidence on clinical outcomes.

This study has several limitations. We defined cage subsidence and its progression as ≥2 mm. This threshold was set to minimize the measurement bias among reviewers; therefore smaller subsidence may have been overlooked.

We could not analyze the effect of cage width on endplate injury, as only 18-mm cages were available in our country; this might account for results that differed from those in previous literature1,2).

In conclusion, intraoperative endplate injury was significantly related to bone quality, and late-onset settling was related to cage type (PEEK cage). Late-onset settling demonstrated a fusion rate worse than that of intraoperative endplate injury or no-subsidence at postoperative 1 year. However, there were no significant differences in clinical outcomes among the subsidence patterns. Further follow-up is necessary to clarify the influence of cage subsidence on clinical outcomes in LIF.

Conflicts of Interest: Tokumi Kanemura holds an advisory role in AOSpine, NuVasive, DePuySynthes Japan, and Medtronic Japan. Other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Le TV, Baaj AA, Dakwar E, et al. Subsidence of polyetherethrketone intervertebral cages in minimally invasive lateral retroperitoneal transpsoas lumbar interbody fusion. Spine. 2012;37(14):1268-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marchi L, Abdala N, Oliveira L, et al. Radiographic and clinical evaluation of cage subsidence after stand-alone lateral interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19(1):110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malham GM, Ellis NJ, Parker RM, et al. Clinical outcome and fusion rates after the first 30 extreme lateral interbody fusions. Scientific World J. 2012;2012:246989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozgur BM, Aryan HE, Pimenta L, et al. Extreme lateral interbody fusion (XLIF): a novel surgical technique for anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2006;6(4):435-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashizume H, Konno S, Takeshita K, et al. Japanese orthopaedic association back pain evaluation questionnaire (JOABPEQ) as an outcome measure for patients with low back pain: reference values in healthy volunteers. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(2):264-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi JY, Sung KH. Subsidence after anterior lumbar interbody fusion using paired stand-alone rectangular cages. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(1):16-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee N, Kim KN, Yi S, et al. Comparison of outcomes of anterior-, posterior- and transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion surgery at a single lumbar level with degenerative spinal disease. World Neursurg. 2017;S1878-8750(17):30140-7. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tohmeh AG, Khorsand D, Watson B, et al. Radiographical and clinical evaluation of extreme lateral interbody fusion: effect of cage size and instrumentation type with a minimum of 1-year follow-up. Spine. 2014;39(26):E1582-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santoni BG, Alexander GE 3rd, Nayak A, et al. Effects on inadvertent endplate fracture following lateral cage placement on range of motion and indirect spine decompression in lumbar spine fusion constructs: A cadaveric study. Int J Spine Surg. 2013;7:e101-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tokuhashi Y, Ajiro Y, Umezawa N. Subsidence of metal interbody cage after posterior lumbar interbody fusion with pedicle screw fixation. Orthopedics. 2009;32(4):259-64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malham GM, Parker RM, Blecher CM, et al. Assessment and classification of subsidence after lateral interbody fusion using serial computed tomography. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;23(5):589-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belkoff SM, Maroney M, Fenton DC, et al. An in vitro biomechanical evaluation of bone cements used in percutaneous vertebroplasty. Bone. 1999;25(2 Suppl):23-6S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hou Y, Luo Z. A study on the structural properties of the lumbar endplate. Spine. 2009;34(12):E427-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park SH, Park WM, Park CW, et al. Minimally invasive anterior lumbar interbody fusion followed by percutaneous translaminar facet screw fixation in elderly patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;10(6):610-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaidya R, Sethi A, Bartol S, et al. Complications in the use of rhBMP-2 in PEEK cages for interbody spinal fusions. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(8):557-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant JP, Oxland TR, Dvorak M. Mapping the structural properties of the lumbosacral vertebral endplates. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(8):889-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vadapalli S, Sairyo K, Goel VK, et al. Biomechanical rationale for using polyetheretherketone (PEEK) spacers for lumbar interbody fusion-A finite element study. Spine. 2006;31(26):E992-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nemoto O, Asazuma T, Yato Y, et al. Comparison of fusion rates following transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion using polyetheretherketone cages or titanium cages with transpedicular instrumentation. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(10):2150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cabraja M, Oezdemir S, Koeppen D, et al. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: comparison of titanium and polyetheretherketone cages. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spruit M, Falk RG, Beckmann L, et al. The in vitro stabilising effect of polyetheretherketone cages versus a titanium cage of similar design for anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Eur Spine J. 2005;14(8):752-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olivares-Navarrete R, Hyzy SL, Slosar PJ, et al. Implant materials generate different peri-implant inflammatory factors: poly-ether-ether-ketone promotes fibrosis and microtextured titanium promotes osteogenic factors. Spine. 2015;40(6):399-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steffen T, Tsantrizos A, Fruth I, et al. Cages: designs and concepts. Eur Spine J. 2000;9(Suppl 1):S89-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanida S, Fujibayashi S, Otsuki B, et al. Vertebral endplate cyst as a predictor of nonunion after lumbar interbody fusion: comparison of titanium and polyetheretherketone cages. Spine. 2016;41(20):E1216-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]