Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization aims to eliminate the hepatitis C virus (HCV) as a public health threat by 2030. Injecting drug use (IDU) is an important risk factor for HCV transmission, but the contribution to country-level and global epidemics is unknown. We estimated the contribution of IDU-associated risk to HCV epidemics at country and global levels.

Methods

A dynamic, deterministic HCV transmission model simulated country-level HCV epidemics among people who inject drugs (PWID) and the general population. Each country’s model was calibrated using country-specific data from UN datasets and systematic reviews on the prevalence of HCV and IDU. The population attributable fraction (tPAF) of HCV transmission associated with IDU was estimated, defined here as the percentage of HCV infections prevented if additional HCV transmission due to IDU was removed between 2018–2030.

Findings

The model included 88 countries (85% of the global population). The model predicted 0.2% of individuals were PWID in 2017 and 8% of prevalent HCV infections were among people who recently injected drugs. Globally, if elevated HCV transmission risk among PWID was removed, an estimated 43% (95% credibility interval [CrI]: 25%−67%), the tPAF, of incident HCV infections would be prevented from 2018–2030, varying regionally. The tPAF was higher (79%, CrI: 57%−97%) in high-income countries than low and middle-income countries (38%, CrI: 24%−64%) and was associated with the percentage of a country’s prevalent infections that are among PWID.

Interpretation

Unsafe injecting practices among PWID contribute substantially to incident infections globally; any intervention that can reduce transmission among PWID will have a pronounced effect on country level incidence.

Funding

NIHR

Keywords: HCV, PAF, Burden, IDU, Inject, Intravenous, PWID, Global Health

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a bloodborne virus that causes substantial morbidity1. Globally, it is estimated that over 70 million individuals are chronically infected with HCV, with around 400,000 HCV-related deaths occurring annually1,2. The World Health Organization (WHO) has set ambitious targets to eliminate hepatitis C virus (HCV) as a public health threat by 20303, which involve reducing incident infections by 80% from their 2015 levels and reducing HCV-related mortality by 65%3. Injecting drug use (IDU) is an important risk factor for the transmission of bloodborne viruses, due to sharing of used needles and injecting equipment4. Although HCV prevalence amongst people who inject drugs (PWID) is generally high (>30%)4, the prevalence of IDU in most countries is low (<1% of adults)4. It is therefore generally assumed that IDU is usually only an important contributor to HCV transmission in low prevalence settings, mainly high-income countries (HICs) in Europe, Australasia, and North America5. Conversely, its role in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), some of which have higher HCV prevalence2, is thought to be small6. In these settings, it is assumed that transmission is driven by other risk factors, such as unsterile medical injections, other medical procedures, unscreened blood transfusions, and community risks (e.g. barbering, tattooing, and body piercings)5–7.

Two recent analyses attempted to quantify the role of IDU to the transmission and disease burden of HCV8,9. These estimated two very distinct measures; the proportion of global prevalent HCV infections that are amongst people who have recently injected drugs, around 8.5%8, and the proportion of the global HCV morbidity burden attributable to IDU, roughly 39%9. Neither measured the full and future HCV transmissions resulting from IDU and neither accounted for current or ex-injectors infected due to IDU conferring additional transmission risk through iatrogenic or other routes. This transmission can be through routes such as tattooing in prisons10, mother-to-child transmission11, needlestick injuries to healthcare workers12, and general access to healthcare leading to iatrogenic transmission13.

Policy-makers should plan the most efficient use of resources to prevent and treat HCV infections in response to the WHO’s 2030 elimination targets3. To do this, it is important to understand the future role of IDU to HCV transmission. To address this knowledge gap, we use country-specific HCV transmission modelling to estimate the contribution of IDU to HCV transmission at the country-level, regionally, and globally. We estimate the proportion of HCV infections that would be prevented from 2018–2030 if HCV transmission due to injecting risks were removed.

Methods

Model description

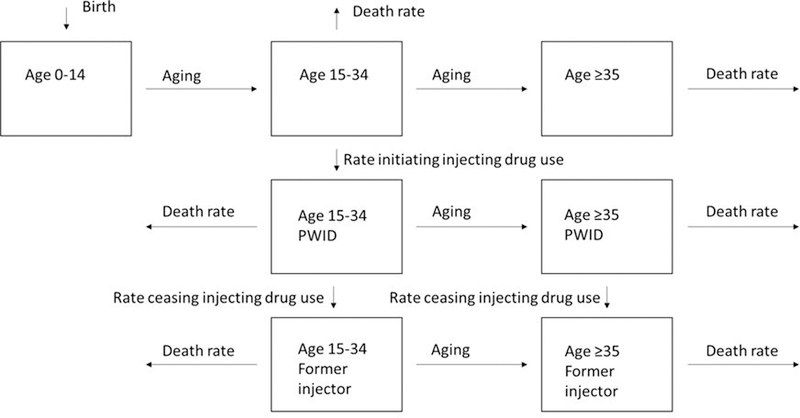

We used a dynamic, deterministic HCV transmission model to simulate country-level HCV epidemics among the general population and PWID, incorporating age distributions, population growth, and HCV progression. We modelled three age-groups: 0–14, 15–34, and ≥35–year olds, with the middle age group selected to approximate the age range that individuals start injecting, using information from Degenhardt et al. New-borns enter the youngest group and then progress through the age-groups. We stratified adults (≥15 years) into individuals who had never injected drugs, PWID (defined as people who currently inject drugs), and people who previously injected drugs (supplementary figure 1, appendix p4). Only young adults (15–34-year olds) were assumed to initiate injecting. All PWID ceased to inject at a fixed rate to become people who previously injected drugs.

Most individuals enter the model susceptible to infection. HCV transmission occurs due to IDU among PWID, or otherwise from risk-factors representing medical and community risk-factors for all people. Mother-to-child transmission of HCV results in some individuals entering the model chronically infected. This occurs at a rate dependent on the number of HCV-infected women of childbearing age (modelled as 15–34) and their HIV co-infection prevalence14. Once infected, individuals either spontaneously clear their infection, and become susceptible again, or develop life-long chronic infection. Those chronically infected progress through different HCV-related disease stages (chronic, compensated, and decompensated cirrhosis). Individuals with decompensated cirrhosis have increased HCV-related mortality.

Modelled HCV treatment occurs at historical rates that are carried forward from 2017. A proportion of those treated achieve a sustained virologic response (SVR) and become susceptible to re-infection, which occurs at the same rate as primary infection. The rest remain chronically infected. Following successful treatment, no further disease progression occurs if individuals had chronic infection15. Continued slower progression occurs among those with cirrhosis15. All individuals die at age-specific death rates. Current PWID experience elevated death from drug-related mortality16. The supplementary materials describe further model details.

Model parameterization

Country-specific data from recent systematic reviews, particularly Blach et al2 and Degenhardt et al4, and United Nations (UN) datasets were used to parameterize and calibrate the model, including data on the prevalence of HCV among PWID and the general population, estimates for the population proportion of PWID, and data on population growth rates and age distributions. Supplementary table 4 (appendix p10) gives details on the sources of the data used. Supplementary Table 10 (appendix p39) gives estimates for country-level HCV prevalences and the population proportion of PWID. The study by Degenhardt et al, from which most estimates of injecting population sizes were taken, states that they preferentially selected size and HCV prevalence estimates that defined current injectors as individuals that have injected drugs in the previous 12 months. However, other estimates using alternative definitions (eg. injecting in the last 6 months) were still included in the review in the absence of the preferred definition. For country-level HCV prevalence estimates, HCV antibody prevalence was taken from the reviews, and was adjusted using region-specific viraemic rates to estimate the prevalence of chronic infection in the survey year17. Historical treatment numbers were taken from various sources, which are described in the supplementary materials. All key parameters had uncertainty associated with them, with bounds generally obtained directly from studies. Where bounds were unavailable for prevalence inputs, ±33% uncertainty bounds were applied, which equates to the median level of uncertainty for those parameters that did have bounds - this was to avoid ascribing too much certainty to those estimates with no uncertainty bounds. Parameter estimates, and country-level data are given in supplementary tables 1–2 and 6–9, which provide further information on model parameterization.

Model calibration

The model was calibrated to 88 countries, including 85% of the global population, 92% of the population in HICs, and 83% in LMICs. Only 43% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa was covered by the model, 62% in the Middle East and North Africa and 64% in Latin America, whilst ≥95% of the population in the remaining regions were modelled.

A four-step calibration method, using different sub-models, was used to calibrate the overall model for each country, from 1990 onwards. For each step, we randomly sampled various model parameters and calibration data from their uncertainty bounds, and then estimated other unknown model parameters through calibrating specific sub-models using the nonlinear least-squares fitting function in Matlab version R2018a (the mathematical modelling software). This process of calibration builds on previous published work from our group18,19, using methods similar to those used by others20,21. Samples were generated until 1000 full model fits were obtained for each country. Runs were rejected if they could not fit the calibration data within ±33%, so allowing the same level of uncertainty as for the model parameters. To ensure the quality of the calibration, the resulting fits were checked and compared with the target values, with the average error being in general less than 0.0001%.

The first stage of the calibration process fit a population growth sub-model (sub-model 1) to calculate country-specific population growth rates between 1990 and 2015, fitting to population sizes in 2015. In the next stage, this model was then adapted to include age demographics (sub-model 2) to estimate age-specific death rates in 2015. These death rates were estimated by fitting sub-model 2 to data on the proportion of the population in age-groups 0–14, 15–34, and ≥35 years. For the third stage, this model was then further adapted to include IDU (sub-model 3). The rates that young adults initiate IDU was estimated by fitting sub-model 3 to the country’s proportion of adults that are PWID. Lastly, the model was again extended to include HCV infection (sub-model 4, i.e. the full model). Sampled and fitted parameters from the previous sub-models were used in the full model to estimate HCV transmission rates for IDU and the general population. We did this by fitting the full model to available chronic prevalence estimates among PWID and the general population for a specific year for each country (sub-model 4). The calibration methods are described fully in the supplementary materials.

Given improved blood bank screening22 and a reduction in the re-use of medical syringes23 over recent years, the HCV epidemics for each country were assumed to be in slow decline (about 1% annually), consistent with a recent review2. This was calibrated by seeding the initial epidemic in 1990 at a prevalence that was higher than the available survey estimate that was being calibrated to but with considerable uncertainty (no decrease to 150% of this decrease). The HCV prevalence among PWID was assumed to be stable between 1990 and the year of the survey estimate for all countries due to evidence from a recent systematic review4. The population proportion of PWID among adults was also assumed to be stable between 1990 and the year of the estimate, except for Sub-Saharan African and Eastern European countries where we assumed recent increases (from 1990 onwards) in IDU as suggested by available data24,25. The rationale underlying these assumptions are discussed in detail in the supplementary materials and tested in various sensitivity analyses.

Model analyses

The calibrated models for each country were used to project the HCV epidemic for 12 years up to 2030, defined as the baseline projections for each country. To investigate the degree to which HCV transmission is driven by risks associated with IDU, the population attributable fraction (tPAF) of HCV transmission (incidence) due to IDU in each country, regionally, and globally, was estimated. To do this, the baseline model fits for each country were re-run with the transmission risk due to IDU set to zero from 2018 onwards. For each paired parameter set, the tPAF was estimated over 1 and 12 years as the relative reduction in the overall number of HCV infections over that period from setting the transmission risk due to IDU to zero (from 2018), compared to the baseline projections. The projections for all paired parameter sets from each country were averaged to produce country-specific estimates, which were then combined to produce regional and global estimates with the average tPAFs for each country weighted by that country’s relative burden of HCV compared to the regional or global burden. The variation across the different model fits for each country were used to produce 95% credibility intervals (CrI).

Sensitivity analyses investigated the effect on the tPAF estimates of: (a) general population HCV prevalence being stable, rather than declining from 1990; (b) HCV prevalence among PWID decreasing at the same rate as the general population HCV prevalence, rather than being stable; (c) the proportion of adults that are PWID in 1990 being stable in Eastern Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa, rather than increasing; (d) the same annual HCV treatment numbers, but with half the treatment rate among PWID and double the treatment rate among people with cirrhosis; (e) the rate of initiating injecting in USA increasing 2.9-fold from 2010 onwards, to capture the recent opioid epidemic26; (f) varying the temporal changes in general population HCV prevalence by region; and (g) treating all infected PWID in 2018 as well as removing the additional transmission rate among PWID.

We used generalised linear regression models to determine what country-level factors are associated with the tPAF of HCV due to risks associated with IDU. The 12-year tPAF was logit transformed (log(tPAF/1-tPAF)) as it is a proportion, and was regressed on the covariates for the percentage of the adult population that are PWID, HCV prevalence among PWID, HCV prevalence among the general population, the injecting duration of PWID in the country, the percentage of the country’s prevalent infections that are among PWID, and the World Bank Gross National Income (GNI) per capita (which could possibly act as a confounder for the amount of spending on a country’s healthcare system) – all from 2017. The non-linear association between the tPAF of HCV due to IDU and the percentage of the country’s prevalent infections that are among PWID was plotted using a fractional polynomial model.

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in the study design, or in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

The model was successfully calibrated for 88 countries, as shown in Figure 1. For the countries simulated, the model predicts that in 2017 0.23% (95% CrI: 0.16%−0.31%) of the global population are PWID and 8% (95% CrI: 5%−12%) of all HCV infections are among people who currently inject drugs.

Figure 1:

Schematic of model showing how people move through the seven age and injecting drug use compartments. PWID denotes people who inject drugs.

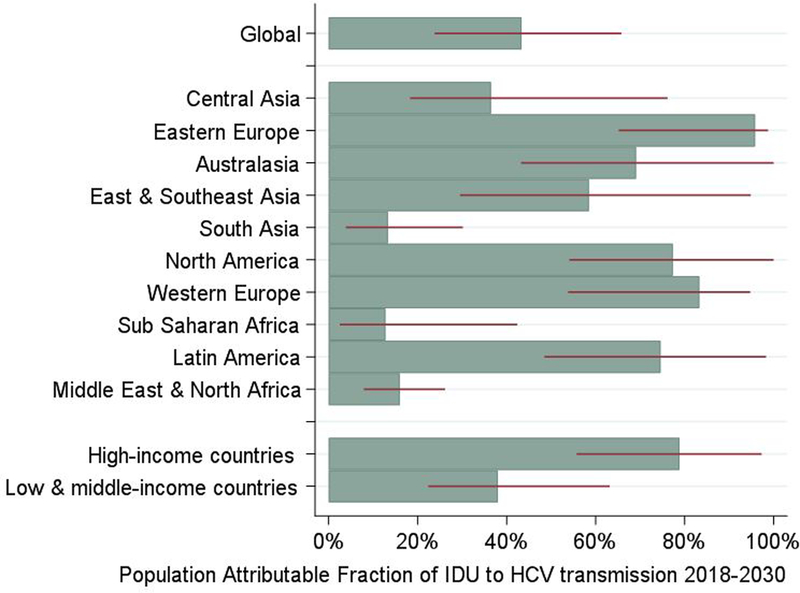

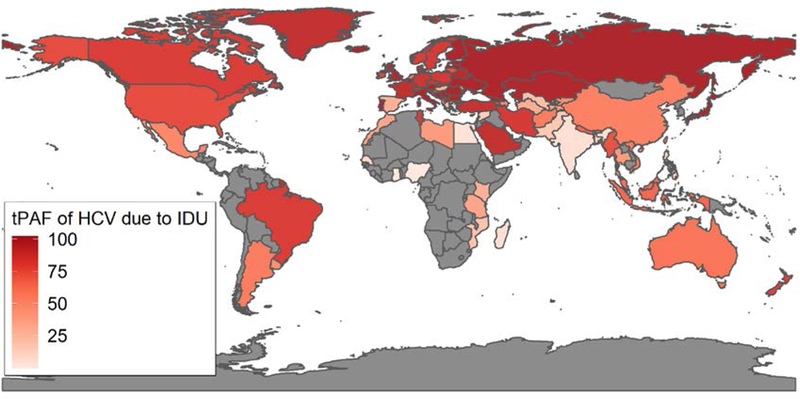

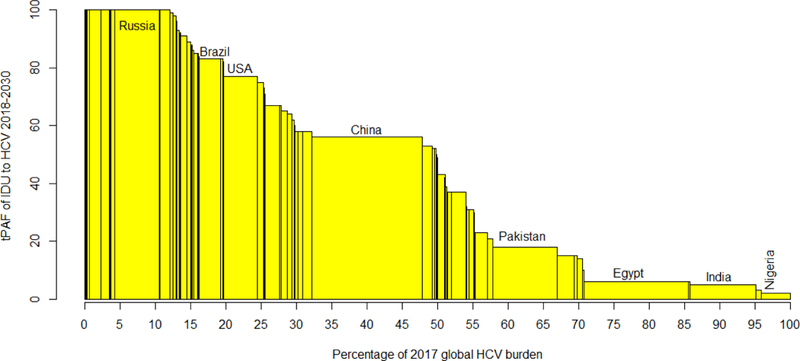

Table 1 and figure 2 show the regional and global estimates of the tPAF of IDU-associated risks to HCV transmission, with the 12-year country-level tPAFs shown in figures 3 and 4 and supplementary table 10 (appendix p39). Globally, the model estimates 43% (95% CrI: 25%−67%) of all new HCV infections could be prevented over 12-years if the heightened HCV risk associated with IDU was removed, varying from 14% (95% CrI: 2%−43%) in Sub-Saharan Africa to 96% (95% CrI: 69%−99%) in Eastern Europe. The 12-year tPAFs of IDU to HCV are over 50% for five other global regions: Western Europe, North America, Latin America, Australasia, and East and Southeast Asia, while they are less than 50% for Central Asia, South Asia, and Middle East and North Africa. The contribution of IDU to HCV transmission is greatest in HICs, where 79% (95% CrI: 57%−97%) of new HCV infections could be prevented if the transmission risk due to IDU was removed, compared to 38% (95% CrI: 24%−64%) in LMICs. The 1-year global tPAF for IDU over 2018–19, 39% (95% CrI: 21%−64%), is slightly lower than the 12-year tPAF (2018–2030).

Table 1:

Regional averaged fitted prevalence estimates in 2017, and model projections of the Population Attributable Fraction (tPAF) of injecting drug use (IDU) to Hepatitis C virus (HCV) transmission from 2018 to 2019 (1-year tPAF) and 2030 (12-year tPAF) – all with 95% credibility intervals. We also give the percentage of that setting’s prevalent infections in 2017 that are amongst PWID to compare with the tPAF. The tPAF is defined as the percentage of all new HCV infections that would be prevented if the transmission risk due to IDU was removed over this period.

| Fitted demographic data values | tPAF of HCV infections due to IDU | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | % of Adults that are PWID |

Chronic HCV prevalence (%) among PWID |

Chronic HCV prevalence (%) among general population |

Percentage of the setting’s prevalent infections that are among PWID |

2018–2019 | 2018–2030 |

| Global | 0.32 (0.23, 0.42) | 34.5 (25.8, 42.0) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) | 8 (5, 12) | 39% (21%, 64%) | 43% (25%, 67%) |

| Central Asia | 0.61 (0.44, 0.81) | 26.4 (21, 29.8) | 2.4 (1.5, 3.3) | 4 (3, 6) | 32% (16%, 69%) | 37% (19%, 73%) |

| Eastern Europe | 1.13 (0.71, 1.61) | 45.8 (34.0, 53.6) | 2.0 (1.2, 2.6) | 21 (12, 31) | 95% (64%, 99%) | 96% (69%, 99%) |

| Australasia | 0.60 (0.46, 0.73) | 35.7 (32.0, 39.3) | 0.8 (0.7, 1.1) | 19 (13, 24) | 58% (34%, 94%) | 66% (43%, 96%) |

| East & Southeast Asia | 0.23 (0.19, 0.28) | 31.5 (23.8, 38.2) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) | 7 (5, 10) | 53% (26%, 98%) | 58% (32%, 98%) |

| South Asia | 0.09 (0.07, 0.11) | 30.3 (16.2, 44.0) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) | 2 (1, 3) | 10% (3%, 25%) | 14% (4%, 31%) |

| North America | 1.08 (0.63, 1.51) | 30.7 (22.2, 40.7) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | 30 (16, 47) | 67% (43%, 100%) | 77% (56%, 100%) |

| Western Europe | 0.32 (0.23, 0.40) | 37.9 (27.3, 44.7) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.0) | 15 (10, 20) | 80% (45%, 93%) | 83% (53%, 94%) |

| Sub Saharan Africa | 0.40 (0.26, 0.55) | 14.2 (10.5, 17.7) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.2) | 3 (1, 4) | 11% (2%, 39%) | 14% (2%, 43%) |

| Latin America | 0.44 (0.35, 0.53) | 49.7 (44.1, 52.8) | 0.8 (0.7, 1.0) | 18 (14, 23) | 66% (41%, 98%) | 71% (49%, 98%) |

| Middle East & North Africa | 0.24 (0.17, 0.30) | 31.7 (23.6, 36.8) | 2.5 (2.0, 3.1) | 2 (1, 3) | 13% (6%, 25%) | 16% (8%, 28%) |

Figure 2:

Regional and global estimates for the Population Attributable Fraction (tPAF) of the risks associated with injecting drug use (IDU) to Hepatitis C virus (HCV) transmission from 2018-2030. Medians shown in bars, with 95% credibility intervals shown with red lines.

Figure 3:

Map of Population Attributable Fraction (tPAF) of HCV transmission due to the risks associated with IDU from 2018–2030. This was calculated as the percentage of all new HCV infections that would be prevented over 2018–2030 if the additional transmission risk due to IDU was removed over this period. Countries in grey were not modelled due to a lack of data.

Figure 4:

Bar chart of each country’s population attributable fraction (tPAF) of the risks associated with injecting drug use to hepatitis C virus (HCV) transmission 2018–2030 against the percentage of the global prevalent HCV infections (2017) in that country. Countries with the largest chronic HCV burdens in 2017 are labelled.

Supplementary tables 11 and 12 (appendix p42 and p44, respectively) show the results of various sensitivity analyses, with the most important changes indicating the tPAF could be lower, 33% (95% CrI: 20%−54%), if the HCV prevalence trends among the general population were assumed to be stable instead of decreasing, or 30% (95% CrI: 15%−51%) if trends varied by region. Sensitivity analyses also showed that the tPAF for USA rose from 67% (95% CrI: 41%−100%) in the baseline model to 85% (95% CrI: 62%−100%) when we assumed an increasing epidemic of IDU since 2010, This increase occurs due to there being 2.9 times more PWID in the modified model during the analysis period than for the baseline model. The sensitivity analyses where we separately assumed (i) a decreasing HCV prevalence among PWID, (ii) the population proportion of PWID in Eastern Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa was stable from 1990 (rather than increasing), (iii) treatment rates are halved among PWID and doubled among people with cirrhosis, did not alter the global tPAF estimate. Lastly, supplementary table 13 (appendix p45) shows that the global tPAF increases to 46% (95% CrI: 26%−65%) if the heightened burden of HCV among PWID was also removed as well as their elevated transmission risk.

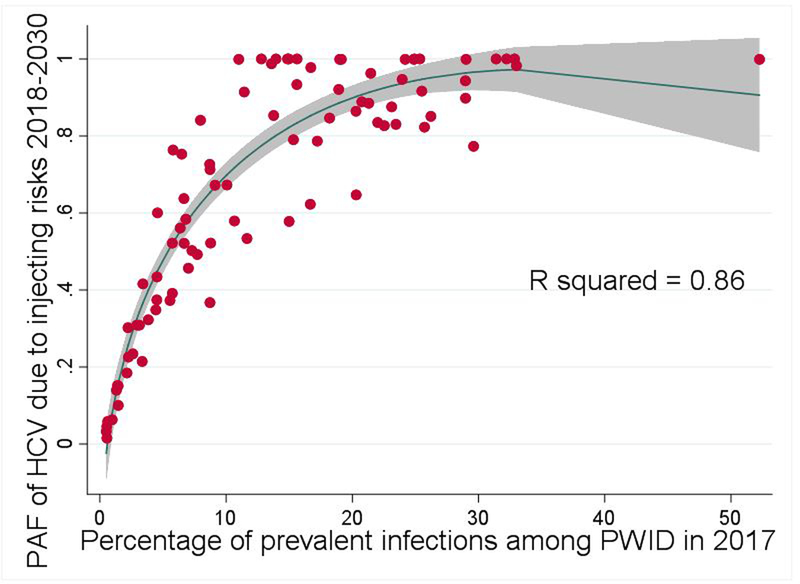

Figure 5 shows there is a strong, positive association between the 12-year tPAF for each country and the percentage of the country’s prevalent infections that are among PWID. In univariable regression analyses (table 2), the logit transformed country-level tPAF increases linearly with the percentage of a country’s prevalent infections that are among PWID, the country’s GNI coefficient, HCV prevalence among PWID, and the population percentage of PWID. In the multivariable model, only the percentage of a country’s prevalent infections that are among PWID was associated with higher 12-year tPAF.

Figure 5:

Scatter plot of the association between the Population Attributable Fraction (tPAF) of the risks associated with injecting drug use (IDU) to Hepatitis C virus (HCV) transmission from 2018–2030 and the percentage of the country’s prevalent infections that are among PWID in 2017 for each country (the red dots). The blue line is a plotted line of best fit* and the grey area is the 95% confidence interval. *Model equation: tPAF=−0.3149-(0.0372*P_PWID)+(0.4376*P_PWID1/2), where P_PWID is the percentage of the country’s prevalent infections that are among PWID

Table 2:

Univariable and multivariable coefficients (with 95% confidence intervals) of the associations between the Population Attributable Fraction (tPAF) of injecting drug use to Hepatitis C virus (HCV) transmission from 2018–2030, logit transformed, and demographic and epidemic-related variables. The tPAF is defined as the percentage of all new HCV infections that would be prevented over 2018–2030 if the additional transmission risk due to IDU was removed over this period.

| Dependent variable: tPAF (logit transformed) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% confidence interval) | ||

| Variable* | Univariable | Multivariable |

| GNI per capita (per $1000)** | 0.05 (0.00, 0.10) [p=0.039] | 0.01 (−0.04, 0.07) [p=0.64] |

| Population percentage of PWID in adults | 2.62 (0.75, 4.49) [p=0.0066] | 1.14 (−1.21, 3.50) [p=0.34] |

| HCV prevalence among PWID*** | 0.09 (0.02, 0.17) [p=0.014] | 0.05 (−0.02, 0.12) [p=0.12] |

| HCV prevalence among general population*** | −0.29 (−1.34, 0.75) [p=0.58] | −0.07 (−1.28, 1.13) [p=0.903] |

| Injecting duration (years) | 0.21 (−0.00, 0.42) [p=0.053] | −0.22 (−0.46, 0.02) [p=0.071] |

| Percentage of the country’s prevalent infections that are among PWID | 0.26 (0.18, 0.34) [p<0.0001] | 0.26 (0.13, 0.38) [p<0.0001] |

GNI: Gross National Income

All variables are from 2017 except for injecting duration which is taken from surveys covering a variety of years for each country.

Syria is missing data on GNI per capita.

HCV prevalence measures are proportions, not percentages

Discussion

Despite PWID comprising less than 0.5% of the global adult population and only contributing 8% of prevalent infections, removing the transmission risk due to IDU could prevent nearly one-half (43%) of all new HCV infections globally from 2018–2030. This varied by country and regions. In sub-Saharan Africa, where the epidemic is thought to be driven by medical transmission27, just over one-tenth of infections are due to the elevated risk associated with IDU, whereas in Eastern Europe it is over nine-tenths of infections. In HICs, about twice as many infections (79%) would be prevented from removing the transmission risk due to IDU than in LMICs (38%). Interestingly, the percentage of a country’s prevalent infections that are among PWID is strongly, positively associated with the tPAF, as this takes into account the size of the PWID population as well as the prevalence of HCV among them. For example, if 5% of the country’s prevalent infections are among current injectors then the estimated tPAF is 48%, which increases to 70% if 10% of prevalent infections are among PWID.

Comparison with other literature

To our knowledge, no paper has estimated the future contribution of IDU-related risk to HCV transmission at a global level. Two papers have estimated the current contribution of IDU to the global burden of HCV infection or disease8,9, but neither accounted for the chain of transmission that can occur in the general population due to individuals that were infected through IDU. Degenhardt et al estimated that 39% of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) for HCV in 2013 were due to IDU9, consistent with the magnitude of our estimate despite using a very different outcome and methodology. Grebely et al. calculated 8.5% of all prevalent HCV infections globally were among PWID, comparable to our estimate of 8% for prevalent infections in 20178. Grebely et al.’s estimate is useful for guiding screening and treatment campaigns but does not address the importance of IDU to future HCV transmission. Otherwise, global modelling by Blach et al. simulated the overall HCV epidemics in different countries but did not model person-to-person HCV transmission or the role of IDU2. Lastly, our results appear to broadly agree with national estimates of the burden of HCV due to injecting risks in the Netherlands and the UK,28,29 with these analyses suggesting that 28% of current infections in the Netherlands are due to IDU28, within the credibility intervals of our estimate (3–31%), and 34% of the UK’s current HCV burden is among PWID29, very similar to our projections (33%, 95% CrI: 24%−42%).

Strengths and limitations

Our modelling is comprehensive in coverage as the analysis uses data from HCV epidemics in 88 countries, comprising 85% of the world’s population. We account for the role of heightened risk among PWID in these HCV epidemics, and incorporate country-level demographic information, population growth, and vertical transmission. Importantly, we account for all incident infections that result from individuals infected due to IDU, and the effect this has on the general population’s HCV incidence and prevalence. This enables us to more accurately estimate the role that IDU has on the overall epidemics in each country. Despite this, our analysis has limitations.

The data on the prevalence of IDU, and the prevalence of HCV amongst PWID and the general population were variable in quality, possibly impacting on our results. For the former two quantities this is partly due to the illicit nature of IDU, which makes PWID a difficult population to study and to enumerate accurately. Data for these three quantities came from existing systematic reviews, and we modelled all countries that had an estimate for each. This meant that for some data estimates it was unclear how they were compiled, some were old, and some were uncertain.

Taking data from disparate sources means some of country-level tPAF estimates may be imprecise. However, it is hard to quantify how this affects our results without additional data. Data-quality scores are shown in supplementary table 8, with 46% of countries having a low scored general population HCV prevalence estimate, and 20% and 39% of country estimates for HCV prevalence among PWID and the proportion of adults that inject drugs, respectively, having low scores. Although the majority of these key data points scored highly, only 19 countries had all three of these key prevalence parameters scored as moderate or better, whilst 66 countries have at least two of these parameters scored moderate or better. These 19 and 66 countries account for 32% and 76% of the global population, respectively. It is possible that the PAF projections for the remaining countries may change when better data becomes available, with better data being most needed for the HCV prevalence in the general population and the size estimates of PWID populations. When only considering the 66 countries with better data, the global average PAF increases slightly to 49% (95% CrI: 29%−73%) emphasising that not including projections from the countries with worse quality data does not substantially affect our projections.

Additionally, some country’s tPAF estimates were lower than expected, including Spain (31%), Greece (23%), and Australia (62%); previous evidence for these countries has suggested most transmission was among IDU5. This discrepancy may be due to data issues, or HCV-epidemic factors, such as historically high levels of IDU that have now decreased, under-estimates of PWID prevalence, or possibly high numbers of migrants with higher HCV risk than the background population. Other modelling from the Netherlands has suggested that most HCV infections were among migrants28. We did not incorporate migration in our model due to insufficient data to do this and uncertainty around key assumptions, such as their HCV prevalence.30 Although not explicitly included, we would consider incoming infections due to migration as something that contributes to the non-IDU transmission aspect of the model, just as we would for medical and community transmission. Similarly, we were unable to include HCV epidemics among MSM within our model due to a scarcity of information around prevalences globally. However, studies indicate that although transmission among MSM is much higher than among heterosexual couples, incidence and prevalence is still low compared with PWID31 and likely contributes little to the epidemic in comparison32.

We also did not explicitly model what makes up the non-IDU component of HCV transmission, which could be due to medical injections, tattooing, body-piercing, barbering, etc. Unfortunately, detailed country-level data on these behaviours were unavailable. Despite these issues, other country-level estimates seem to agree with our model28,29, with the low tPAFs of IDU in some HICs implying that our global tPAF estimate for IDU may be conservative. Also, general insights about how the tPAF is related to different country-level factors should still hold.

Another limitation of our analysis is that our deterministic models did not capture the network effects of how HCV transmits among PWID, which has been shown to be important for assessing the impact of interventions for HCV33,34. This paper is less concerned in this question, rather its main aim is to determine how the observed epidemic among PWID may contribute to overall levels of transmission in that country.

For almost all countries included, there is little to no published data to determine the likely ongoing evolution of each country’s HCV epidemic. To counter this, we gathered available evidence on reductions in HCV transmission risks due to improved blood transfusion safety22 or reductions in unsafe medical injections23, and so assumed that the modelled global epidemic was in decline, consistent with modelling by Blach et al2. However, there is considerable uncertainty in this assumption, so we assumed wide uncertainty bounds and undertook sensitivity analyses where we either assumed each country’s HCV prevalence trends were stable or varied by region, which both projected lower tPAFs (about 30–33%). Importantly, country-level HCV epidemic trajectories are highly uncertain with only three countries having two repeated national surveys, highlighting the need for further data on this. Additionally, the systematic reviews used for this analysis, although from 2017, lacked data from recent years where HCV outbreaks have occurred among PWID in some countries, notably USA26 where a higher tPAF is estimated when this is assumed. The lack of robust data on HCV prevalence, especially for the general population, also raises concerns about whether countries will be able to reliably ascertain their progress towards WHO’s HCV elimination targets or develop plans to reach them. This highlights the crucial role of good data for policy-making. Importantly, a single inaccurate data point could affect a country’s results, implying that careful consideration of the assumptions made is required before using our results to inform policy in specific countries.

Despite the limitations described above, it is also important to note that this paper utilises data from 12 reviews, synthesising data from thousands of studies and accounting for the uncertainty in these estimates in our projections. This will have minimised the data issues as far as is currently possible, with our extensive sensitivity analyses showing that the overall finding that IDU is an important contributor to the global HCV epidemic is robust despite data uncertainties.

Implications

To our knowledge, this is the first study to fully quantify the future contribution of IDU to the global HCV epidemic. The results show that the elevated risks associated with IDU account for 43% of global HCV infections over the next 12 years; with this figure being even higher in HICs (79%). This information is primarily useful for policy-makers that are uncertain about the importance of combating the HCV epidemic amongst PWID, especially for meeting the WHO’s 2030 elimination targets3. Indeed, globally, our results suggest the incidence of HCV in PWID needs to be reduced by at least half to have any hope of reducing the overall incidence of HCV by 80%. Such a reduction in incidence can be achieved through reducing prevalence or transmission risks, including via micro elimination initiatives that either scale-up HCV treatment for PWID or prevention interventions35, such as needle and syringe provision (NSP) and OST programs. Newly synthesised data and modelling has shown that these interventions can dramatically reduce levels of HCV incidence26,36, can be cost-effective in various settings36,37, and can also prevent other blood-borne viruses such as HIV38. However, the current coverage of NSP and OST is low in most countries,39 as is the coverage of direct acting antiviral drug treatment40, with PWID being frequently denied treatment41. Barriers restricting the coverage of these interventions need to be urgently addressed to achieve the WHO HCV elimination targets.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

To gather literature on the burden of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) epidemic that was due to injecting drug use, searches were performed in Pubmed with the terms (“IDU” or “PWID” or “IVDU” or “injection drug” or “injecting drug” or “intravenous drug” or “people who inject drugs”) and (“burden” or “PAF” or “Population attributable”) and (“HCV” or “hepatitis C”). Four previous papers were found that have investigated the importance of injecting drug use to the HCV burden nationally or globally in terms of infection or disease. In 2016 a modelling analysis by Degenhardt et al estimated that around 39% of the 2013 HCV disease burden in terms of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) was due to injecting drug use, whilst a 2018 analysis by Grebely et al calculated that 8.5% of prevalent HCV infections globally were among people with recent injecting drug use. Nationally, a 2013 study by Vriend et al estimated that around 28% of current infections in the Netherlands were through injecting drug use, whilst a 2018 study by Harris et al estimated that around 34% of the UK’s current HCV burden was among current injectors.

Added value of this study

This is the first study to quantify the contribution of injecting drug use to overall levels of HCV transmission at country, regional, and global levels. Eighty-eight countries, comprising 85% of the global population, were modelled. Globally, if the HCV transmission risk due to unsterile needle and syringe sharing among people who currently inject drugs was removed, then our modelling suggests that 43% of incident HCV infections would be prevented between 2018 and 2030, varying from 14% in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia to 96% in Eastern Europe. For high-income countries, the percentage of incident HCV infections that would be prevented is around twice as high (79%) as in low or middle-income countries (38%). The percentage of the country’s prevalent infections that are among PWID is strongly related to the proportion of incident HCV infections prevented when the transmission risk due injecting drug use is removed.

Implications of all the available evidence

This modelling indicates the substantial contribution that injecting drug use makes to the global HCV epidemic. For many settings, scaling up HCV prevention and treatment interventions for people who inject drugs, including needle and syringe provision and opioid substitution therapy, will be essential to meet World Health Organization 2030 elimination targets.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge everyone involved in the systematic reviews used as data for this study. We would also like to acknowledge Andrew Hill for assistance with the historical treatment numbers.

Funding

AT’s PhD has been funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Units (NIHR HPRUs) in Evaluation of Interventions at the University of Bristol in partnership with Public Health England. JG is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship. NKM, HF, and PV were partially supported by the National Institute for Drug Abuse [R01 DA037773]. NKM was additionally supported by the University of San Diego Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), a NIH funded program (P30 AI036214). LD and SL are supported by NHMRC Research Fellowships (GNT1041742, GNT1135991, GNT1091878, GNT1140938) and NIDA R01DA1104470. The National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre at UNSW Sydney is supported by funding from the Australian Government Department of Health under the Drug and Alcohol Program. MTM, PV and MH are supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Units (NIHR HPRUs) in Evaluation of Interventions at the University of Bristol in partnership with Public Health England (PHE). MTM is also supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, the Department of Health or Public Health England.

Declaration of interest statement

JG is a consultant/advisor and has received research grants from AbbVie, Cepheid, Gilead Sciences and Merck/MSD. In the past 3 years, LD has received investigator-initiated untied educational grants for studies of opioid medications in Australia from Indivior, Mundipharma, and Seqirus. SL has received investigator initiated untied educational grants from Indivior. AP has received investigator-initiated untied educational grants from Mundipharma and Seqirus. MH reports personal fees from Gilead, Abbvie, and MSD. PV reports grants from Gilead, outside the submitted work. HF has received an honorarium from MSD. NKM has received unrestricted research grants and honoraria from Gilead and Merck.

Footnotes

The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Hepatitis C Fact sheet. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/.

- 2.Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 2(3): 161–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Combating hepatitis B and C to reach elimination by 2030. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Degenhardt L, Peacock A, Colledge S, et al. Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. Lancet Glob Health 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(17): 2436–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5(9): 558–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tohme RA, Holmberg SD. Transmission of hepatitis C virus infection through tattooing and piercing: a critical review. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54(8): 1167–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grebely J, Larney S, Peacock A, et al. Global, regional, and country-level estimates of hepatitis C infection among people who have recently injected drugs. Addiction 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Stanaway J, et al. Estimating the burden of disease attributable to injecting drug use as a risk factor for HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16(12): 1385–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hellard ME, Aitken CK, Hocking JS. Tattooing in prisons - Not such a pretty picture. Am J Infect Control 2007; 35(7): 477–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Resti M, Azzari C, Galli L, et al. Maternal drug use is a preeminent risk factor for mother-to-child hepatitis C virus transmission: Results from a multicenter study of 1372 mother-infant pairs. J Infect Dis 2002; 185(5): 567–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Public Health Service for Wales. All-Wales Inoculation Injury Guidelines for Primary Care. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Candelas F, Guiral S, Carbo R, et al. Patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis C virus (HCV) during colonoscopy diagnosis. Virol J 2010; 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benova L, Mohamoud YA, Calvert C, Abu-Raddad LJ. Vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59(6): 765–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158(5 Pt 1): 329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Lemon J, Wiessing L, Hickman M. Mortality among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2013; 91: 102–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petruzziello A, Marigliano S, Loquercio G, Cozzolino A, Cacciapuoti C. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: an up-date of the distribution and circulation of hepatitis C virus genotypes. World J Gastroentero 2016; 22(34): 7824–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraser H, Martin NK, Brummer-Korvenkontio H, et al. Model projections on the impact of HCV treatment in the prevention of HCV transmission among people who inject drugs in Europe. Journal of Hepatology 2018; 68(3): 402–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim AG, Qureshi H, Mahmood H, et al. Curbing the hepatitis C virus epidemic in Pakistan: the impact of scaling up treatment and prevention for achieving elimination. Int J Epidemiol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayoub HH, Abu-Raddad LJ. Impact of treatment on hepatitis C virus transmission and incidence in Egypt: A case for treatment as prevention. J Viral Hepat 2017; 24(6): 486–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corson S, Greenhalgh D, Hutchinson SJ. A time since onset of injection model for hepatitis C spread amongst injecting drug users. J Math Biol 2013; 66(4–5): 935–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prati D Transmission of hepatitis C virus by blood transfusions and other medical procedures: a global review. J Hepatol 2006; 45(4): 607–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pepin J, Abou Chakra CN, Pepin E, Nault V, Valiquette L. Evolution of the global burden of viral infections from unsafe medical injections, 2000–2010. PLoS One 2014; 9(6): e99677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Trends in Injecting Drug use in Europe. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giles-Vernick T, Webb J. Global Health in Africa, Historical Perspectives on Disease Control. 2013: 211–34. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraser H, Zibbell J, Hoerger T, et al. Scaling-up HCV prevention and treatment interventions in rural United States-model projections for tackling an increasing epidemic. Addiction 2018; 113(1): 173–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karoney MJ, Siika AM. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in Africa: a review. Pan Afr Med J 2013; 14: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vriend HJ, Van Veen MG, Prins M, Urbanus AT, Boot HJ, De Coul ELM. Hepatitis C virus prevalence in The Netherlands: migrants account for most infections. Epidemiology and Infection 2013; 141(6): 1310–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris R, Harris H, Mandal S, et al. Monitoring the hepatitis C epidemic in England and evaluating intervention scale-up using routinely collected data. J Viral Hepatitis 2018; (In press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uddin G, Shoeb D, Solaiman S, et al. Prevalence of chronic viral hepatitis in people of south Asian ethnicity living in England: the prevalence cannot necessarily be predicted from the prevalence in the country of origin. J Viral Hepat 2010; 17(5): 327–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yaphe S, Bozinoff N, Kyle R, Shivkumar S, Pai NP, Klein M. Incidence of acute hepatitis C virus infection among men who have sex with men with and without HIV infection: a systematic review. Sexually Transmitted Infections 2012; 88(7): 558–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacGregor L, Martin NK, Mukandavire C, et al. Behavioural, not biological, factors drive the HCV epidemic among HIV-positive MSM: HCVand HIV modelling analysis including HCV treatmentas- prevention impact. International Journal of Epidemiology 2017; 46(5): 1582–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zelenev A, Li JH, Mazhnaya A, Basu S, Altice FL. Hepatitis C virus treatment as prevention in an extended network of people who inject drugs in the USA: a modelling study. Lancet Infectious Diseases 2018; 18(2): 215–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott N, Hellard M, McBryde ES. Modeling hepatitis C virus transmission among people who inject drugs: Assumptions, limitations and future challenges. Virulence 2016; 7(2): 201–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lazarus JV, Safreed-Harmon K, Thursz MR, et al. The Micro-Elimination Approach to Eliminating Hepatitis C: Strategic and Operational Considerations. Semin Liver Dis 2018; 38(3): 181–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Platt L, Minozzi S, Reed J, et al. Needle syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Db Syst Rev 2017; (9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mabileau G, Scutelniciuc O, Tsereteli M, et al. Intervention Packages to Reduce the Impact of HIV and HCV Infections Among People Who Inject Drugs in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: A Modeling and Cost-effectiveness Study. Open Forum Infect Di 2018; 5(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson DP, Donald B, Shattock AJ, Wilson D, Fraser-Hurt N. The cost-effectiveness of harm reduction. Int J Drug Policy 2015; 26 Suppl 1: S5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larney S, Peacock A, Leung J, et al. Global, regional, and country-level coverage of interventions to prevent and manage HIV and hepatitis C among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health 2017; 5(12): e1208–e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. Access to hepatitis C treatment 2018. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenthal ES, Kattakuzhy S, Kottilil S. Time to end treatment restrictions for people with hepatitis C who inject drugs. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.