Abstract

Background

Having comprehensive knowledge about HIV is crucial in the fight against HIV and AIDS, and in achieving the global aspiration of ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. Low comprehensive knowledge about HIV can undercut efforts to halt the spread of the epidemic. It is important, however, to also determine if socioeconomic inequality is a factor in having a comprehensive knowledge about HIV in order to ensure that socioeconomic considerations are embedded in interventions. In this paper, the objective is to assess trends, as well as socioeconomic related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV in Malawi.

Methods

The current study uses a non-parametric approach and the concentration index. It draws upon secondary data from three rounds of the Malawi Demographic and Health Survey (MDHS) of 2004, 2010 and 2016.

Results

Our results point to an increase in comprehensive knowledge about HIV over the 12-year period, from 28% in 2004 to around 44% in 2016. However, upon using the Erreygers concentration index, a wealth related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV is uncovered. The poorer are less informed and the richer are better informed: comprehensive knowledge about HIV is concentrated among the rich. Furthermore, inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV has worsened over this period. Across gender, there is greater inequality among men than women. However, the rural-urban difference in wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV dropped in 2016.

Conclusion

The results show that comprehensive knowledge about HIV has increased. Furthermore, it is established that comprehensive knowledge about HIV is concentrated among the wealthier in the 2004 -2016 period. Our results suggest that there should be a targeted approach in messaging and disseminating information regarding HIV and AIDS, using methods that are pro-poor.

Keywords: HIV and AIDS, comprehensive knowledge about HIV, inequality, gender, Erreygers, Malawi

Introduction

Attainment of good health and well-being for all is among the objectives of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda1,2. The HIV and AIDS pandemic is a potential challenge to the achievement of these goals3 and remains the greatest cause of mortality in low and middle income countries (LMICs)4,5. Malawi and the rest of Sub Saharan Africa (SSA) remain severely affected, with nearly 1 in every 25 adults (4.2%) in the region living with HIV. In 2016, around 21,000–31,000 AIDS related deaths were reported in Malawi6. The new HIV infection rate is still high and one potential explanation lies in the low comprehensive knowledge about HIV. Comprehensive knowledge about HIV is seen as pivotal in combating the epidemic7–9. While low comprehensive knowledge about HIV is reported in Malawi10, evidence on the existence of socioeconomic inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV, as well as its trend and size, remains scanty.

Against this background, the main objective of this paper is to investigate the presence of socioeconomic inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV in Malawi. We contribute to the existing literature in several ways. Firstly, we quantify the extent of socioeconomic inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV using a concentration index. Secondly, we assess the trends in relation to comprehensive knowledge about HIV and wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV. Finally, we examine the gender and geographical differences in socioeconomic inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV. More importantly, we also contribute by undertaking the first health equity analysis on this topic using health concentration indices. This study is important since Malawi did not achieve the Millennium Development Goal on HIV and AIDS despite being successful in reducing the incidence of HIV10–12. Hence this paper attempts to explain the possible cause of the failure.

Methods

The health concentration index has frequently been used to measure socioeconomic inequalities in health outcomes and health related variables13–17. The concentration index is a family of bivariate rank dependent indices. A bivariate index measures the distribution of inequality in health based on the ranking of individuals in a society, along the measure of socioeconomic status. With this index, the analysis can be stratified by time (often in years), gender, or any other socioeconomic dimension.

There are many ways of algebraically expressing a concentration index (CI). The standard concentration index equation is expressed as:

CI=2/(µ) cov(hi,Ri) (1)

where CI is equal to the covariance between individual health (h_i) (in this paper it is comprehensive HIV knowledge) and the individual's relative rank (R_i) in the cumulative wealth distribution (wealth status is measured by the wealth index), weighted by the mean of health in the population (µ). What the above expression implies is that CI is a measure of the degree of association between an individual's level of comprehensive knowledge about HIV and their relative position in the income distribution13.The CI ranges between −1 and +1. A negative (positive) index shows that a lack of comprehensive knowledge about HIV is concentrated in individuals with relatively low (high) wealth status. If CI is zero, the implication is that there is no wealth-related inequality in the distribution of comprehensive knowledge about HIV.

The standard CI assumes that the health outcome of interest is continuous. In the context of discrete variables, standard CI is limited since it does not satisfy the mirror property. In addition, the value of the concentration index depends on the mean of the variable in the population of interest. For binary variables, such as the dependent variable in this study, alternative measures have been proposed in recent years15,17–19. Erreygers15 proposed different weighting functions to normalize the concentration index for binary (bounded) outcomes called the Erreygers index (EI). The EI is expressed as:

EI=4µ/(hmax-hmin)*CI (2)

where h^max and h^min are the theoretical upper and lower bounds of the bounded variable. This study applies the EI concentration index since our variable of interest is binary. The choice of Erreygers stems from the recommendation from both empirical and theoretical literature that the index is appropriate for binary variables15,19–21. In the following sections, we use the terms EI and CI synonymously to mean the Erreygers concentration index.

Definition of comprehensive knowledge about HIV

In this analysis, we use the standard definition for comprehensive knowledge about HIV that was developed by the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), and as used in the current rounds of Demographic Health Surveys (DHS). Knowledge of HIV prevention is defined as: (1) knowing that both condom use and limiting sexual intercourse to one uninfected partner are HIV prevention methods; (2) knowing that a healthy-looking person can have HIV, and finally rejecting the two most common local misconceptions about HIV transmission namely; (3) knowing that HIV cannot be transmitted by mosquito bites or (4) knowing that HIV cannot be transmitted by supernatural means. If all four responses apply, comprehensive knowledge about HIV takes a value of one, and zero otherwise. This definition has been used in over 90 countries to assess the level of comprehensive knowledge about HIV. This definition is standard in all places where DHS is conducted . Several studies have also assessed comprehensive knowledge about HIV across the world9,22–28 using this definition.

We measure socioeconomic status using the wealth index. This is the conventional measure recommended when there is no income data or expenditure data29. Construction of a wealth index typically uses principal component methods and it is the measure of socioeconomic status used by the DHS for international comparison32,33.

Data source

Our analysis uses data from the Malawi Demographic and Health Survey (MDHS). The data for MDHS in the context of Malawi was collected by the MEASURE DHS, National Statistical Office (NSO), and Ministry of Health (MoH). MDHS is part of the global MEASURE DHS program in more than 90 countries worldwide. The DHS are cross-sectional surveys conducted in developing countries since 1984. The MDHS uses a two-stage sampling framework in both rural and urban areas. DHS data is freely available on their website34. We used data from three rounds of MDHS in the years 2004, 2010 and 2016. In all the data sets, the response rate was as high as 95%. Whilst we appreciate that preference is given to the most recent data, using multiple time points allows for a more compelling trend analysis. Since this study used secondary data, no ethical clearance was necessary; this had already been done by the NSO with the Ministry of Health and the National Health Research Commission (NHRSC) at the time of the surveys10,24,35. In total, the sample size is 76,455 respondents after we controlled for some missing observations.

Results

This section presents the study's findings and we start our analysis by presenting the univariate statistics of the data used and the variables analysed, in Table 1. Thereafter, we present the trends in comprehensive knowledge about HIV and then finish by analysing the trend and differences in wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV. As can be seen from Table 1, 28.0% of respondents had comprehensive knowledge about HIV in 2004; 41.0% in 2010; and 44.7% in 2016. This represents an average of 40.1% in the period 2004 -2016. This is quite low, but is similar to other countries in SSA9,36,37. In terms of gender, the distribution is around 23.2% of men (see the column for pooled statistics). However, it is noteworthy that the percentage of respondents who can be considered wealthier has been increasing over time, as can be observed from the changes in the numbers in the income quintiles of the various years.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| 2004(N=14,878) | 2010(N=29,744) | 2016(N=31,991) | Total (N=76455) | |||||

| Variables | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n |

| Comprehensive knowledge about HIV | 28.0 | 4116 | 41.0 | 12193 | 44.7 | 14314 | 40.1 | 30623 |

| Sex respondent (1= male, 0=female) | 22.0 | 3232 | 23.7 | 7058 | 23.3 | 7467 | 23.2 | 17757 |

| Urban (1=urban, 0 = rural) | 14.5 | 2130 | 13.6 | 4042 | 21.6 | 6900 | 17.1 | 13072 |

| Northern region (1= North, 0 =Otherwise) | 13.8 | 2033 | 18.2 | 5401 | 19.9 | 6369 | 18.1 | 13803 |

| Central region (1= Central, 0= Otherwise) | 36.3 | 5337 | 34.5 | 10273 | 34.6 | 11073 | 34.9 | 26683 |

| Southern region (1= Southern, 0= Otherwise) | 49.9 | 7350 | 47.3 | 14070 | 45.5 | 14549 | 47.0 | 35969 |

| Poorest (quintile1) (1= quintile1, 0= Otherwise) | 16.5 | 2433 | 18.8 | 5578 | 16.6 | 5321 | 17.4 | 13332 |

| Poorer (quintile2) (1= quintile2, 0= Otherwise) | 20.0 | 2944 | 19.7 | 5858 | 17.9 | 5738 | 19.0 | 14540 |

| Middle (quintile3) (1= quintile3, 0= Otherwise) | 21.8 | 3216 | 20.5 | 6101 | 18.6 | 5944 | 20.0 | 15261 |

| Richer (quintile4) (1= quintile4, 0= Otherwise) | 21.4 | 3144 | 20.6 | 6142 | 20.2 | 6453 | 20.6 | 15739 |

| Richest (quintile5) (1= quintile5, 0= Otherwise) | 20.3 | 2983 | 20.4 | 6065 | 26.7 | 8535 | 23.0 | 17583 |

Trends in comprehensive knowledge about HIV prevalence over time

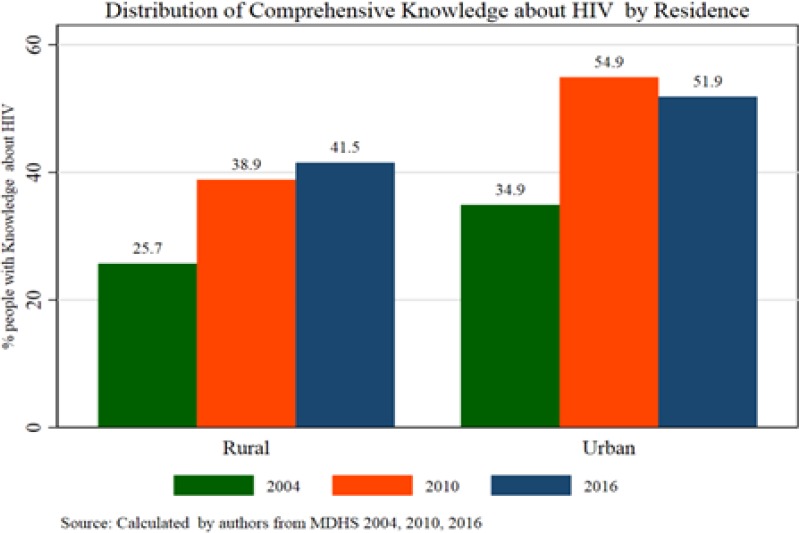

Our main results are presented in both figures and tables. The first part involves the presentation of trends in comprehensive knowledge about HIV over the period, in Figures 1, 2 and 3. Figure 1 depicts an increasing trend in comprehensive knowledge about HIV since 2004. In 2004, the percentage of people with comprehensive knowledge about HIV was 27.4% where, in terms of urban and rural differentials, 34.9% of respondents in urban areas had comprehensive knowledge about HIV compared to 25.7% in rural areas.

Figure 1.

Percentage of people with comprehensive knowledge about HIV in Rural and urban

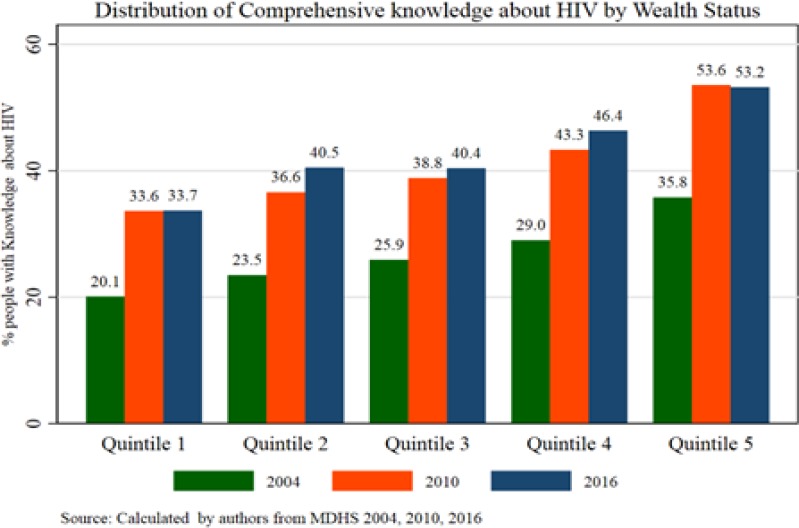

Figure 2.

Percentage of people with Comprehensive Knowledge about HIV by wealth status

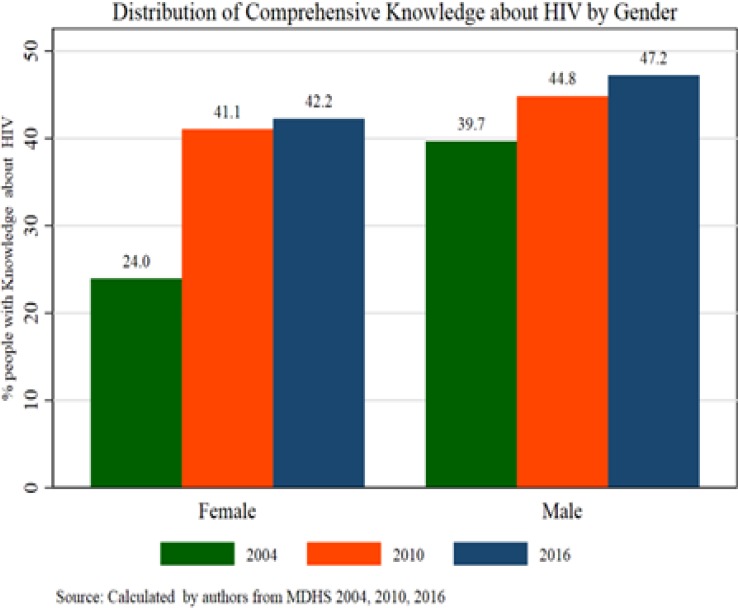

Figure 3.

Percentage of people with Comprehensive Knowledge about HIV by gender

As of 2010, there was an improvement from 2004 such that 42.0% of respondents had comprehensive knowledge about HIV (54.9% and 38.9% in urban and rural areas respectively). Overall the percentage of people with comprehensive knowledge about HIV was 43.5% (51.9% in urban and 41.5% in rural areas). In all cases, the 2004 values were lower. However, a surprising result was observed in the urban figures in 2016. The 2016 value is lower than that of 2010.

The results suggest that there is a rural-urban gap (difference) in the rate of comprehensive knowledge about HIV. When assessed across wealth status, Figure 2 shows two clear trends in terms of comprehensive knowledge about HIV. First, in all the years under study, comprehensive knowledge about HIV increased alongside wealth status. Second, the proportion of people with comprehensive knowledge about HIV was higher among the wealthier for all the years. For 2004, the values remained lower than the rest of the other years. In 2016, the proportion of people with comprehensive HIV knowledge was the same for the middle and lower wealth quintile. Overall, the observed pattern suggests possible wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV. Gender differences in comprehensive knowledge about HIV were also assessed, and this is presented in Figure 3.

The biggest gender gap was observed in 2004; 24.0% of females and 39.7% of males had comprehensive knowledge about HIV. As of 2010, the gap had reduced: 44.8% of males and 41.1% of females had HIV comprehensive knowledge. The difference in the 2010 figures on comprehensive knowledge about HIV across gender was about 3.0 %. A similar margin of difference (around 4%) was observed in 2016. The gender-gap seems to have substantially declined since 2004. It might thus be of interest to assess what contributed to the considerable gap equalisation.

Trends in wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV

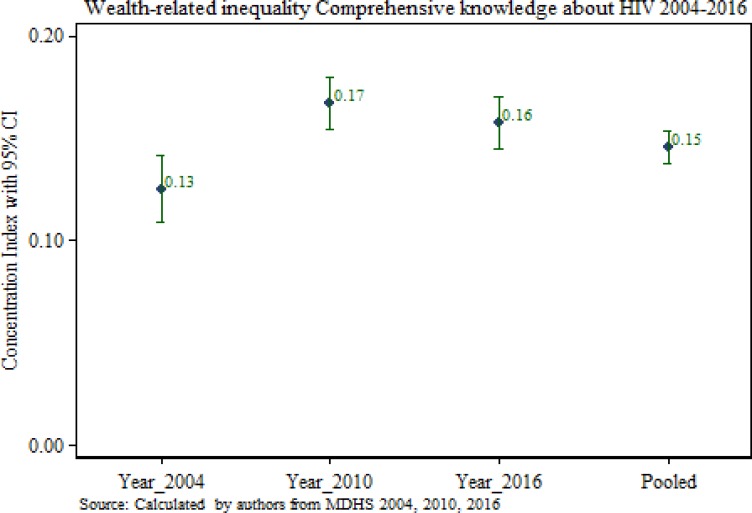

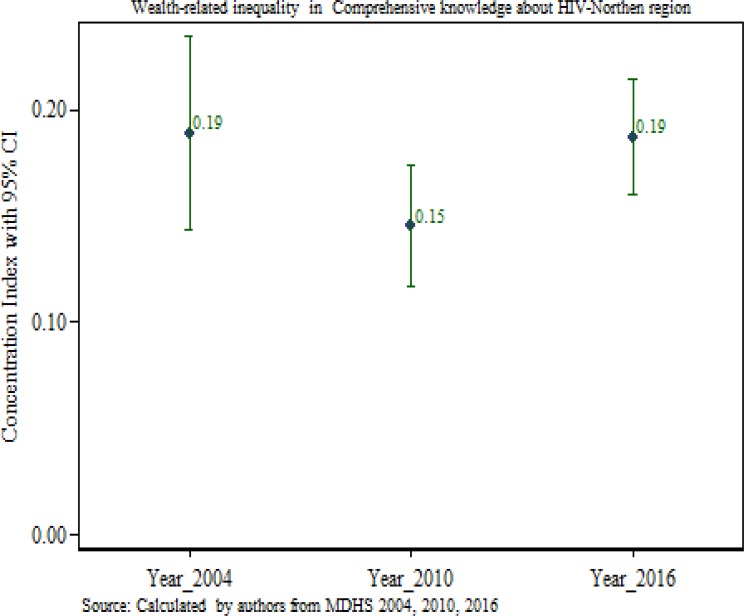

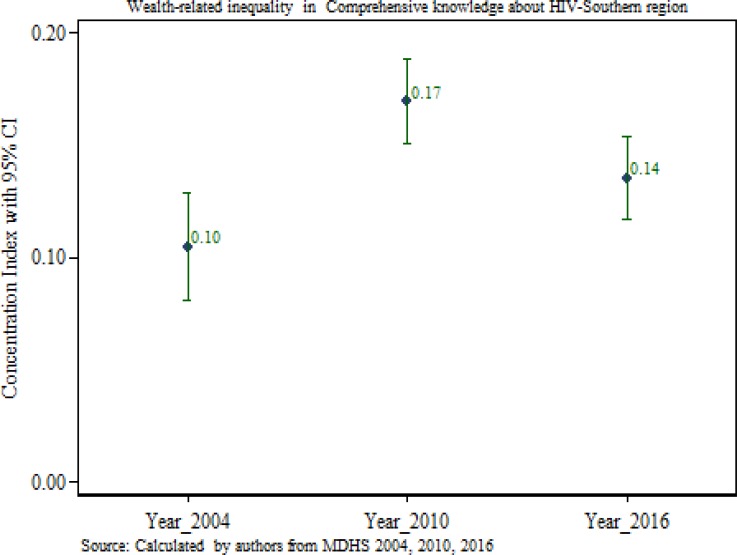

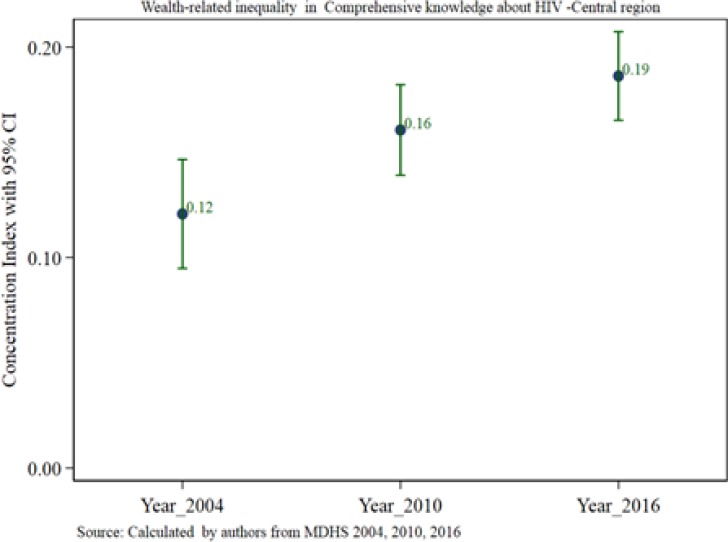

Beyond the general trends described previously, we also applied the concentration index as a standard tool for measuring socioeconomic related inequality in any health variable. Figure 4 shows the intensity magnitude and trends in socioeconomic inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV. Our results in Figure 4 mimic the pattern shown in the prevalence of HIV comprehensive knowledge across the wealth distribution in Figure 2. As stated earlier, when the index moves towards zero, it implies that the wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV is low. The figure shows that inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV had worsened in the years 2004 to 2016. From 2004 to 2010 the index moved from 0.13 to 0.17, and thereafter, it partially declined to 0.16 by 2016. Overall, the index was at 0.15, suggesting pro-rich disparities in comprehensive knowledge about HIV. We also assessed the wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV across administrative regions in order to give a more nuanced picture of the pattern of socioeconomic inequalities in comprehensive knowledge about HIV in Malawi. These are presented in figures 5 to 7. In all the administrative regions, the values of the concentration indices are positive and significantly different from zero at a 5% level of significance. This highlights a pro-rich distribution in comprehensive knowledge about HIV in all the administrative zones. In Figure 5, there is no difference in the levels of inequality in 2004 and 2016 in the northern region, save for a partial decline in 2010. Figure 6 illustrates a trend in wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV for the central region. As opposed to the other regions, inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV followed an upward trend for all years, implying that there is worsening inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV. For the southern region, as displayed in Figure 7, the index increased from 0.10 in 2004 to 0.14 in 2016.

Figure 4.

Erreygers Concentration index trend for comprehensive knowledge about HIV 2004–2016 (pooled sample)

Figure 5.

Erreygers concentration index trend for comprehensive knowledge about HIV 2004–2016: Northern Region

Figure 7.

Erreygers concentration index trend for comprehensive knowledge about HIV 2004–2016: Southern Region

Figure 6.

Erreygers concentration index trend for comprehensive knowledge about HIV 2004–2016: Central Region

Gender difference in inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV

Table 2 presents three panels for male (A), female (B) and the difference between the concentration indices for males and females (C). The associated sample sizes and p-values are also indicated. In columns (A) and (B), we find that all the concentration indices are positive and significantly different from zero. This implies that there are pro-rich socioeconomic disparities in comprehensive knowledge about HIV, among both males and females. Furthermore, it is clear that among men, inequality has been increasing from an index of 0.120 to 0.179. For women the pattern is similar to that of the concentration indices for men, but it was worse in 2010 compared to the other years. When compared across the gender divide, wealth-inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV is worse among men than women in 2016 only, unlike in the other years (this can be seen under a title heading “difference” in the table). Our results, after stratifying the analysis by urban/rural locations, are shown in Table 3. Just like in Table 2, results are presented in three panels for urban (A), rural (B) and the difference between the concentration indices for urban and rural (C). The associated sample size and p-values are also indicated. In columns (A) and (B), we found that all the concentration indices are positive and significantly different from zero, implying there is a pro-rich distribution in comprehensive knowledge about HIV in both rural and urban locations. Both the rural and urban areas register increasing wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV, in favour of the rich from 0.125 in 2004 to 0.157 in 2016). In 2004, there was more inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV in rural than in urban areas, a feature which reversed in 2016. However, there is no statistically significant difference in socioeconomic related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV in 2016.

Table 2.

wealth-related inequality in Comprehensive Knowledge about HIV by gender

| (A): Men | (B): Female | (C): Difference (Male-female) | ||||||

| Year | EI | n | p-value | EI | n | p-value | Difference | p-value |

| 2004 | 0.120 | (3247) | 0.000 | 0.118 | (11631) | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.944 |

| 2010 | 0.149 | (7058) | 0.000 | 0.170 | (22686) | 0.000 | −0.020 | 0.185 |

| 2016 | 0.179 | (7467) | 0.000 | 0.148 | (24524) | 0.000 | 0.030 | 0.043 |

| 2004–2016(pooled) | 0.149 | (17772) | 0.000 | 0.133 | (58841) | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.109 |

Table 3.

wealth-related inequality in knowledge about HIV by residence

| (A): Urban | (B): Rural | (C): Difference (urban-rural) | ||||||

| Year | EI | n | p-value | EI | n | p-value | Difference | p-value |

| 2004 | 0.045 | (2137) | 0.000 | 0.107 | (12741) | 0.000 | −0.062 | 0.014 |

| 2010 | 0.141 | (4042) | 0.000 | 0.099 | (25702) | 0.000 | 0.042 | 0.028 |

| 2016 | 0.145 | (6900) | 0.000 | 0.128 | (25091) | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.031 |

| 2004–2016(pooled) | 0.124 | (13079) | 0.000 | 0.088 | (63534) | 0.000 | 0.035 | 0.001 |

Discussion

On trends in comprehensive knowledge about HIV

This paper represents the first attempt to quantify and assess trends in socioeconomic inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV in Malawi using the concentration index. Our results reveal rural-urban, wealth, and gender related differences in comprehensive knowledge about HIV. Our findings show that there has been a substantial improvement in comprehensive knowledge about HIV over the decade. The result of increasing comprehensive knowledge about HIV is similar to findings of other studies in other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa9,27,37 and Bangladesh38. Despite the promising trajectory, comprehensive knowledge about HIV remains low (below 50% of the population) just as in many Sub-Saharan African countries, and this is worrisome. The increasing trend in comprehensive knowledge about HIV might be as a result of an increased intensity in HIV programming by the government and its partners between 2004 and 2016. Within that period, the national policy on HIV and AIDS, which emphasized increasing awareness of HIV and AIDS as a catalyst for behaviour change, was developed. The policy was accompanied by the expansion of HIV and AIDS awareness programmes by the various stakeholders in the national HIV response under the leadership of the National AIDS Commission.

Furthermore, over the years HIV and AIDS issues have been mainstreamed into school syllabi at all levels of education (from primary to tertiary levels). At primary school level, a new subject called Life Skills is currently being taught to all students. This subject covers, among other topics, HIV and AIDS. At secondary school level, the topic of HIV and AIDS is part of the Social Studies curriculum. In addition to this, there is also the Life Skills subject which is studied separately, covering various aspects of HIV and AIDS. At tertiary level, HIV and AIDS messages are disseminated through various platforms including HIV and AIDS clubs. University-wide HIV and AIDS awareness initiatives have also sprouted up in recent years, including what is known as Why Wait! at the University of Malawi. At some colleges within the University of Malawi, the orientation program for first year students also includes a slot on HIV and AIDS awareness.

More broadly, as a part of HIV awareness efforts, there has been a shift from the conventional print media to electronic and social media, as well as interactive audio-visual modes. For instance, Tikuferanji, Youth Alert, and Pakachere, which are radio and television programmes, might have had an impact on the dissemination of information about HIV and AIDS. All these programs started around 2004. With the emergence and the predominance of social media, it would also be instructive to take advantage of social media platforms such as WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter.

Wealth status appears to be highly associated with HIV comprehensive knowledge. A positive trend from 2004 to 2016 suggests that comprehensive knowledge about HIV increases with wealth and is higher amongst the richer in Malawi. This result is consistent with other studies22,28 where HIV prevention knowledge was higher among those in the higher wealth quintiles. The reason might be that those with more wealth are better exposed to the modes through which the bulk of HIV and AIDS messaging is disseminated28.

Rural-urban differences in HIV comprehensive knowledge seems to be a major issue. In various parts of Sub-Saharan Africa9,39, Bangladesh40 and Canada41, rural and urban differences in comprehensive knowledge about HIV have been identified. A number of reasons can be put forward to explain this rural-urban differential. Mass media communication in some rural areas is limited due to (tele) communications network limitations. Furthermore, most of the rural areas in Malawi are physically hard to reach. Consequently, even health interventions take longer to reach rural recipients than in urban areas, thereby limiting the extent to which messages can be disseminated in rural areas.

In terms of gender, other studies38,42 also found that comprehensive knowledge about HIV is higher among men. In our analysis, the results suggest that there are no substantial differences in comprehensive knowledge about HIV between men and women in the period from 2004 to 2010, with 2016 as the only exception. The introduction of HIV Counselling and Testing (HCT) and counselling for women during antenatal care might also be a reason for the reduction in the difference in levels of comprehensive knowledge about HIV between males and females.

On inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV

The overall result in terms of wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV over time brings up two crucial messages: first, wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV worsened; and second, wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV is continuing to worsen, in favour of the rich i.e comprehensive knowledge about HIV is concentrated among the wealthier. As can be seen from the Erreygers concentration index, between 2004 and 2010 there was an increase in the index followed by a small decline in 2016.

The worsening wealth-related inequality can potentially be linked to the national wealth disparities43 coupled with the fact that the decline in poverty levels in the country has been slight44. The increasing gap in wealth may put the richer in a better position to access vital information through television, radio and school. The consequence of wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV is that the better off are better informed than the poor. As a result, it may lead to the problem of the poor being more likely to catch HIV, ultimately leading to death. Across gender and location, pro-rich income inequality with respect to comprehensive knowledge about HIV persists.

Our study has several limitations, given its design. For instance, it does not provide causal evidence about whether the issues outlined are the principal drivers of the observed inequality. Furthermore, our outcome variable of interest (comprehensive HIV knowledge) is self-reported and therefore potentially biased. This is a common problem in all data sets that do not use objective measures such as biomarkers. Lastly, our major constraint was a lack of comparable studies that have undertaken a similar analysis using the concentration index approach to health equity analysis, by focusing on HIV knowledge. Therefore, comparison with other studies on this aspect was impossible. On the other hand, this could also be seen as a strength of this paper, in that it sparks a conversation on the equity dimension of comprehensive HIV knowledge using these standard health equity analysis tools and applying them to Malawi. Future studies can investigate community and individual level factors that explain wealth-related inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV, which is one step beyond the analysis presented in this paper.

Conclusions

This study aimed at assessing socioeconomic inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV in Malawi. We have found pro-rich inequalities in HIV related comprehensive knowledge between 2004 and 2016. The trend showed that the inequality worsened over the period. The results of this study provide some policy implications. First, the findings invite policy-makers and program planners, especially those involved in HIV and AIDS behavioural change interventions, to consider the socioeconomic aspect in their programming in general and, with respect to promoting HIV related awareness, to redirect their efforts to the poorer sections of the population. This implies adopting modes of communication that are more pro-poor instead of relying exclusively on television and other electronic media that are mostly accessible to those that are well-to-do. Second, the results suggest that in the medium to long term, economic empowerment interventions may have important spillover effects in HIV programming through eliminating socioeconomic barriers related to having access to information, including information on HIV prevention.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr James Gaughan of The University of York, UK, who proofread the document and offered some further suggestions. Our gratitude also goes to Dr Ken Lipenga Jnr of the University of Malawi, Chancellor College, and Sally Jenkins who completed the language check. We also thank the anonymous reviewers from the Malawi Medical Journal whose suggestions have greatly improved the paper.

Funding and conflict of interest

The authors declare that no funding was received for this study, and that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.United Nations Development Programme [Internet], author Sustainable Develepment goals. [cited 2018 May 22] Available from: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/

- 2.Warren CE, Hopkins J, Narasimhan M, Collins L, Askew I, Mayhew SH. Health systems and the SDGs: lessons from a joint HIV and sexual and reproductive health and rights response. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(suppl_4):iv102–iv107. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx052. 1, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McRobie E, Matovu F, Nanyiti A, Nonvignon J, Abankwah DNY, Case KK, et al. National responses to global health targets: exploring policy transfer in the context of the UNAIDS ‘90-90-90’ treatment targets in Ghana and Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(1):17–33. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx132. 1; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng W, Shepard DS, Avila-Figueroa C, Ahn H. Resource needs and gap analysis in achieving universal access to HIV/AIDS services: a data envelopment analysis of 45 countries. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(5):624–633. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czv109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organisation [Internet], author 10 facts on HIV/AIDS. [cited 2018 February 10] . Available from: https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/hiv/facts/en/index3.html.

- 6.UNAIDS [Internet], author HIV and AIDS facts : Malawi. [cited 2018 March 20]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/malawi.

- 7.Sohn A, Park S. HIV/AIDS Knowledge, Stigmatizing Attitudes, and Related Behaviors and Factors that Affect Stigmatizing Attitudes against HIV/AIDS among Korean Adolescents. Osong Public Heal Res Perspect. 2012;3(1):24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oljira L, Berhane Y, Worku A. Assessment of comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge level among in-school adolescents in eastern Ethiopia. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(1) doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.17349. http://do.org/10.7448/IAS.16.1.17349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teshome R, Youjie W, Habte E, Kassm NM. Comparison and Association of Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Knowledge and Attitude towards people Living with HIV/AIDS among Women Aged 15-49 in Three East African Countries: Burundi, Ethiopia and Kenya. J AIDS Clin Res. 2016;07(04):1–8. doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Statistical Office (NSO) and ICF, author. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015–16. NSO and ICF; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenworthy N, Thomann M, Parker R. Critical perspectives on the ‘end of AIDS.’. Glob Public Health. 2018 doi: 10.1080/17441692.2018.1464589. https://doi.org/10.1080/1744 1692.2018.1464589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health Malawi [Internet], author Malawi Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (MPHIA) 2015–16: First Report. Lilongwe, Malawi: [cited 2018 May17]. Available from: http://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Final-MPHIA-First-Report_11.15.17.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Donnell O, Van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A, Lindelow M. Analyzing Health Equity Using Household Survey Data: A Guide to Techniques and their Implementation. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank; 2008. 165 p. [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Donnell O, O'Neill S, Van Ourti T, Walsh B. conindex: Estimation of concentration indices. Stata J. 2016;16(1):112–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erreygers G. Correcting the Concentration Index. J Health Econ. 2009;28(2):504–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kjellsson G, Gerdtham U-G. On correcting the concentration index for binary variables. J Health Econ. 2013;32(3):659–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke PM, Gerdtham U-G, Johannesson M, Bingefors K, Smith L. On the measurement of relative and absolute income-related health inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(11):1923–1928. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagstaff A. The bounds of the concentration index when the variable of interest is binary, with an application to immunization inequality. Health Econ. 2005;14(4):429–432. doi: 10.1002/hec.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erreygers G, Van Ourti T. Measuring socioeconomic inequality in health, health care and health financing by means of rank-dependent indices: A recipe for good practice. J Health Econ. 2011;30(4):685–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagstaff A. Reply to Guido Erreygers and Tom Van Ourti's comment on ‘The concentration index of a binary outcome revisited’. Health Econ. 2011;20(10):1166–1168. doi: 10.1002/hec.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heckley G, Gerdtham U-G, Kjellsson G. A general method for decomposing the causes of socioeconomic inequality in health. J Health Econ. 2016;48:89–6296. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung M, Arya M, Viswanath K. Effect of Media Use on HIV/AIDS-Related Knowledge and Condom Use in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Opio A, Mishra V, Hong R, Musinguzi J, Kirungi W, Cross A, et al. Trends in HIV-related behaviors and knowledge in Uganda, 1989–2005: evidence of a shift toward more risk-taking behaviors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(3):320–326. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181893eb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NSO and ICF Macro, author. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Zomba, Malawi, and Calverton, Maryland, USA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.NSO and ICF International, author. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015–16: Key Indicators Report. Zomba, Malawi, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.NSO and ORC Macro, author. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2004. Zomba, Malawi and Calverton, Maryland, USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochako R, Ulwodi D, Njagi P, Kimetu S, Onyango A. Trends and determinants of Comprehensive HIV and AIDS knowledge among urban young women in Kenya. AIDS Res Ther. 2011;8(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ackerson LK, Ramanadhan S, Arya M, Viswanath K. Social disparities, communication inequalities, and HIV/AIDS-related knowledge and attitudes in India. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):2072–2081. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0031-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Donnell O, Doorslaer E van, Wagstaff A, Lindelow M. Analyzing Health Equity Using Household Survey Data: A Guide to Techniques and their Implementation. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank; 2008. 165 p. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating Wealth Effects without Expenditure Data-or Tears: An Application to Educational Enrollments in States of India. Demography. 2001;38(1):115–132. doi: 10.2307/3088292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21(6):459–468. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ICF Macro[Internet], author The DHS program-Wealth index construction. [cited 2018 January 20]. Available from: https://www.dhsprogram.com/topics/wealth-index/Wealth-Index-Construction.cfm.

- 33.Rutstein SO, Johnson K. MEASURE DHS, ORC Macro. The DHS wealth index. ORC Macro, MEASURE DHS; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.ICF [Internet], author Demographic health surveys [cited 2018 January 13] Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/

- 35.NSO and ORC Macro, author. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2004. Zomba, Malawi and Calverton, Maryland, USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fenny AP, Crentsil AO, Asuman D. Determinants and Distribution of Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Knowledge in Ghana. Glob J Health Sci. 2017;9(12):32. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v9n12p32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oginni AB, Adebajo SB, Ahonsi BA. Trends and determinants of comprehensive knowledge of HIV among adolescents and young adults in Nigeria: 2003–2013. Afr J Reprod Health. 2017;21(2):26–34. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2017/v21i2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheikh MT, Uddin MN, Khan JR. A comprehensive analysis of trends and determinants of HIV/AIDS knowledge among the Bangladeshi women based on Bangladesh Demographic and Health Surveys, 2007–2014. Arch Public Heal. 2017;75:59. doi: 10.1186/s13690-017-0228-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barden-O'Fallon JL, deGraft-Johnson J, Bisika T, Sulzbach S, Benson A, Tsui AO. Factors associated with HIV/AIDS knowledge and risk perception in rural Malawi. AIDS Behav J. 2004;8(2):131–140. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000030244.92791.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jesmin SS, Chaudhuri S, Abdullah S. Educating Women for HIV Prevention: Does Exposure to Mass Media Make Them More Knowledgeable? Health Care Women Int. 2013;34(3–4):303–331. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.736571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veinot TC, Harris R. Talking About, Knowing About HIV/AIDS in Canada: A Rural-Urban Comparison. J Rural Heal. 2011;27(3):310–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Danhoundo G, Shah V, Ekholuenetale M. Trends and determinants of HIV/AIDS knowledge among women in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):812. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3512-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mussa R, Masanjala W. A Dangerous Divide: The State of Inequality in Malawi 2015. [cited 2018 April 20] [Internet]. Available from: https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/file_attachments/rr-inequality-in-malawi-261115-en.pdf.

- 44.NSO, author. Third Integrated Household Survey (IHS3) 2010/2011. Zomba, Malawi: 2012. [Google Scholar]