Introduction

Verrucous psoriasis (VP) is a rare variant of psoriasis characterized by hyperkeratotic, papillomatous plaques that clinically resemble verrucous carcinoma (VC) in lesion appearance and distribution.1, 2 It is amenable to medical treatments.3, 4, 5 Conversely, VC, a rare subtype of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, is treated with surgical excision.1 Histologically, they may be difficult to differentiate. Ancillary positive p16 staining can help confirm a diagnosis of VC in equivocal cases.

When diagnosing VC, it would be beneficial to consider a differential diagnosis including VP, verruca vulgaris, deep fungal infection, leishmaniasis, and hypertrophic lichen planus, which are responsive to medical treatment. Early consideration of medical therapy in uncertain cases could aid in the avoidance of unnecessary procedures and their complications. We present a patient with VP of the heel that was initially diagnosed as VC and excised. Recovery was complicated by graft breakdown and poor wound healing over 2 years.

Case report

An 81-year-old white man with a history of mild plaque psoriasis, nonmelanoma skin cancer, and alcohol use presented for evaluation of a lesion on the foot that had been enlarging over several months. It was causing tenderness and difficulty walking. He had no recent travel history. Relevant dermatologic medications included clobetasol cream for psoriasis, but he had not been using it because his skin disease had been quiescent.

Physical examination was unremarkable except for a 2 × 2.5–cm, verrucous, well-circumscribed, tan-to-brown plaque on the medial left heel with surrounding erythema. The differential diagnosis favored squamous cell carcinoma versus a deep fungal infection. Two punch biopsies were performed. Histopathology showed an atypical squamous proliferation; the tissue culture result was negative for a fungal infection. Two months later, the patient returned because the lesion had grown to 4 cm (Fig 1). There were no palpable popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes. Repeat biopsy showed hyperkeratosis, an absent granular layer with koilocytosis, carcinomatous epithelial hyperplasia, glassy keratinocytes, spongiosis, and a dense superficial mixed infiltrate (Figs 2 and 3). The dermatopathologist concluded that it was suspicious for VC.

Fig 1.

Verrucous psoriasis plaque on the left medial heel before biopsy and Mohs surgery.

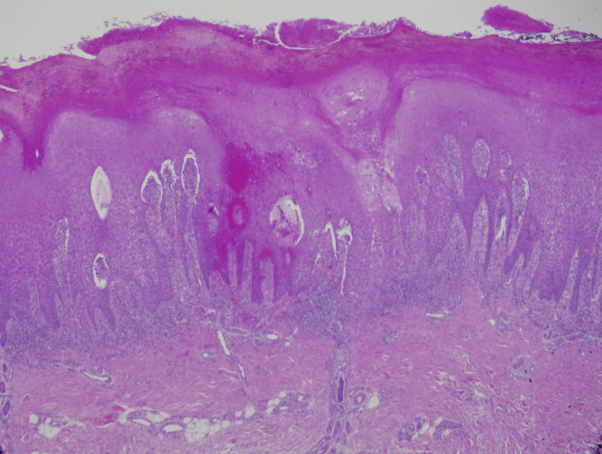

Fig 2.

Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification, ×10. Biopsy of the left medial heel shows hyperkeratosis; an absent granular layer; a hemorrhagic thrombus with admixed neutrophils; acanthosis with elongated rete pegs; and dense, mixed inflammation in the papillary dermis.

Fig 3.

Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification, ×40. Spongiosis, keratinocyte maturation, and mixed inflammation with lymphocytes and eosinophils are apparent.

The case was presented at grand rounds, where a consensus diagnosis of VC was made given the location, clinical appearance, negative infectious stain and culture results, and rapid growth of the lesion. Magnetic resonance imaging of the left leg showed an ill-defined, hypermetabolic soft tissue mass but no calcaneal involvement. A questionable intramuscular mass in the left thigh and hypermetabolic foci within the left fibula prompted a whole-body positron emission tomography scan, the results of which were negative for lymphadenopathy or metastatic foci.

At the time of surgery, the 6 × 6.5–cm lesion was removed via staged excision with en face evaluation of permanent section margins, requiring a total of 2 stages to clear residual squamous atypia; the final size was 8.5 × 8.5 cm. The site was repaired with a split-thickness skin graft. Because of concern that this was an aggressive squamous cell carcinoma, the patient had radiation. The graft and donor sites healed well after the surgery, but over the next 2 years, recovery was complicated by graft breakdown and poor wound healing.

A few months after excision, the patient developed verrucous plaques on the lower legs, forearms, and feet; biopsy specimens showed psoriasiform dermatitis (Fig 4). With the presence of multifocal verrucous plaques in the setting of a history of plaque psoriasis, the patient's diagnosis was revised to VP. At this point, the original plaque was believed to be his first manifestation of VP; of note, his graft did not koebnerize. The patient has also developed painful plantar pustulosis in the 4 years since the excision. His VP and plantar disease have been unresponsive to phototherapy, potent topical steroids, and several biologics. Oral retinoids have been avoided because of the patient's chronic alcohol use.

Fig 4.

The patient developed more verrucous plaques on the lower extremities in subsequent months, with pedal plaques similar to his initial presentation. Histology of plaques on legs was consistent with Figs 2 and 3.

Discussion

VC is a rare subtype of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma that presents in middle-aged to older adults as a large, verrucous, exophytic tumor. Histologically, VC classically has a papillomatous, exophytic architecture with hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis overlying endophytic, bulbous rete pegs. Often described as bulldozing, the blunt rete pegs of VC can extend into the subcutis but have focally infiltrative features and a low mitotic index.6 VC is commonly associated with human papilloma virus (HPV) infection, which can be evaluated with p16 immunohistochemical staining.1 p16 is overexpressed in HPV-driven tumors because of HPV-related E6 and E7 oncogenes inhibiting Rb, leading to p16 disinhibition; a negative test result can help confirm a diagnosis of VP.7, 8 Staining was not pursued in this case because the tumor seemed locally aggressive, so the results would not have changed management.

VP is a rare variant of psoriasis, with fewer than 35 reported cases. It should be suspected in patients with a history of plaque psoriasis who develop hyperkeratotic, papillomatous plaques once infection has been ruled out. VP is commonly distributed in the same areas as VC and is prone to minor trauma-induced koebnerization.2 Treatments for VP are based on case reports and include adalimumab, ustekinumab, etretinate alone, and etretinate combined with topical steroids and topical vitamin D3 under compression.3, 4, 5 Histologically, VP is characterized by regular psoriasiform acanthosis with Munro microabscesses. More prominent epidermal papillomatosis and bowing of rete ridges toward the center, known as epithelial buttressing, is common compared with classic psoriasis.2, 9 Traumatized plaques with pseudoepithelial hyperplasia can make histologic differentiation difficult.

A review of the literature suggests that VP has been previously misdiagnosed as VC. Kuan et al6 reported a case of multifocal VC on the lower legs of a 42-year-old man that resolved with acitretin. The authors stated that the histopathology was consistent with VC's bulldozing invasion of bulbous rete versus a stabbing, narrow-tipped rete infiltration more consistent with VP.6 However, a letter was later published calling the diagnosis of VC into question because of the patient's response to acitretin, with VP a more likely explanation.10 Although the original presentation and histopathologic diagnosis in this case and in our patient suggested VC, there is considerable overlap with the clinical and histopathologic features of VP.

The treatment of choice for VC is excision, which can have significant morbidity due to poor wound healing on the lower extremities. When diagnosing VC, it may be prudent to consider a differential diagnosis including VP, verruca vulgaris, deep fungal infections, and hypertrophic lichen planus because these are amenable to medical treatment.

The similarities between VC and VP may make clinical and histologic differentiation of singular lesions difficult. Ancillary staining with p16 should be performed in equivocal cases. In the case of HPV-negative lesions, thorough history and physical examination may provide evidence of underlying psoriasis. The alert dermatologic surgeon may consider further dermatopathology consultation with clinical correlation before surgery. If the clinician cannot make a clear distinction between VC and VP, medical treatments should be considered, particularly for disease in areas prone to poor wound healing and in poor surgical candidates. Radiation should be used with caution in the lower limbs.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None disclosed.

References

- 1.Bolognia J., Jorizzo J.L., Schaffer J.V. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 2012. Dermatology. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khalil F.K., Keehn C.A., Saeed S., Morgan M.B. Verrucous psoriasis: a distinctive clinicopathologic variant of psoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27(3):204–207. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000157450.39033.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maejima H., Katayama C., Watarai A. A case of psoriasis verrucosa successfully treated with adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(11):e74–e75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okuyama R., Tagami H. Psoriasis verrucosa in an obese Japanese man: a prompt clinical response observed with oral etretinate. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1359–1361. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakamatsu K., Naniwa K., Hagiya Y. Psoriasis verrucosa. J Dermatol. 2010;37(12):1060–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuan Y., Hsu H., Kuo T. Multiple verrucous carcinomas treated with acitretin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(Suppl):S29–S32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis A., Yosipovitch G. Erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23(3):215–218. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2010.550912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabban J.T., Soslow R.A. Immunohistochemistry of the female genital tract. In: Dabb D.J., editor. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry. 3rd ed. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 2010. pp. 690–762. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monroe H.R., Hillman J.D., Chiu M.W. A case of verrucous psoriasis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(5):10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsen F., Susa J., Cockrell C., Abramovits W. Case of multiple verrucous carcinomas responding to treatment with acitretin more likely to have been a case of verrucous psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(3):534–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]