Abstract

The glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor links over 150 proteins to the cell surface and is present on every cell type. Many of these proteins play crucial roles in neuronal development and function. Mutations in 18 of the 29 genes implicated in the biosynthesis of the GPI anchor have been identified as the cause of GPI biosynthesis deficiencies (GPIBDs) in humans. GPIBDs are associated with intellectual disability and seizures as their cardinal features. An essential component of the GPI transamidase complex is PIGU, along with PIGK, PIGS, PIGT, and GPAA1, all of which link GPI-anchored proteins (GPI-APs) onto the GPI anchor in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Here, we report two homozygous missense mutations (c.209T>A [p.Ile70Lys] and c.1149C>A [p.Asn383Lys]) in five individuals from three unrelated families. All individuals presented with global developmental delay, severe-to-profound intellectual disability, muscular hypotonia, seizures, brain anomalies, scoliosis, and mild facial dysmorphism. Using multicolor flow cytometry, we determined a characteristic profile for GPI transamidase deficiency. On granulocytes this profile consisted of reduced cell-surface expression of fluorescein-labeled proaerolysin (FLAER), CD16, and CD24, but not of CD55 and CD59; additionally, B cells showed an increased expression of free GPI anchors determined by T5 antibody. Moreover, computer-assisted facial analysis of different GPIBDs revealed a characteristic facial gestalt shared among individuals with mutations in PIGU and GPAA1. Our findings improve our understanding of the role of the GPI transamidase complex in the development of nervous and skeletal systems and expand the clinical spectrum of disorders belonging to the group of inherited GPI-anchor deficiencies.

Keywords: GPIBD, PIGU, inherited GPI deficiency, glycosylphosphatidylinositol, epilepsy, multicolor flow cytometry, automated facial analysis, deep phenotyping

Main Text

The linkage of over 150 different proteins to the cell surface is facilitated by the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. GPI-anchored proteins (GPI-APs) play important roles in embryogenesis, neurogenesis, signal transduction, and various other biological processes in all tissues of the human body.1, 2 Hence, biosynthesis, modification, and transfer of the GPI anchor to the proteins are highly conserved processes mediated by at least 31 genes. The GPI transamidase is a heteropentameric complex (encoded by PIGK [MIM: 605087], PIGS [MIM: 610271], PIGT [MIM: 610272], GPAA1 [MIM: 603048], and PIGU [MIM: 608528, RefSeq accession number NM_080476.4]) that mediates the transfer of the protein to the GPI anchor in the endoplasmatic reticulum (ER).

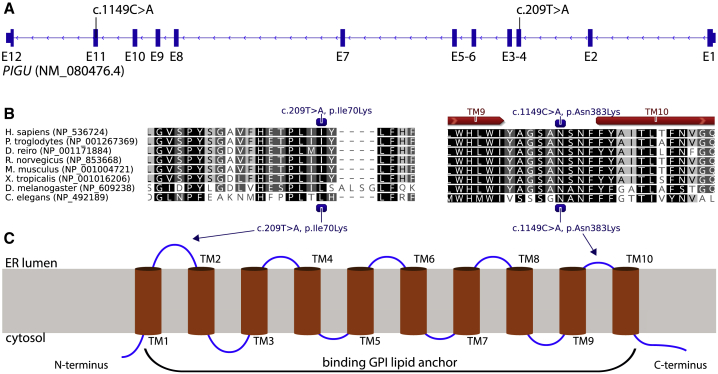

A recent protein-sequence analysis study showed that the ten predicted transmembrane domains (TMs) of PIGU share high sequence similarity with the mannosyltransferases PIGM, PIGV, PIGB, and PIGZ but lack functionally important motifs.3 These ten TMs were anticipated to bind the GPI lipid anchor. In addition, it was determined that PIGU is the last component that associates with the core protein complex of the GPI transamidase formed by PIGT, PIGS, PIGK, and GPAA1.4 Therefore, the presumed molecular function of PIGU is the presentation of the GPI lipid anchor to the transamidase complex in a productive conformation.3

Mutations in three genes of the GPI transamidase complex have been associated with human disease. Severe intellectual disability, global developmental delay, muscular hypotonia, seizures, and cerebellar atrophy were described in individuals with GPAA1 (GPIBD15 [MIM: 617810])5 and PIGT mutations (GPIBD7 or multiple congenital anomalies-hypotonia-seizures syndrome 3 [MCAHS3 (MIM: 615398)]);6 PIGS deficiency leads to severe global developmental delay, seizures, hypotonia, ataxia, and dysmorphic facial features (GPIBD18 [MIM: 618143]).7 Here, we describe five individuals from three unrelated families with rare biallelic missense mutations in PIGU presenting with global developmental delay, severe-to-profound intellectual disability, muscular hypotonia, seizures, brain anomalies, scoliosis, and mild facial dysmorphism consistent with GPI biosynthesis deficiencies (GPIBDs).8, 9 We provide clinical and functional evidence for a form of a severe autosomal-recessive GPIBD caused by pathogenic mutations in PIGU.

Proband P-1 was the first daughter of healthy first-degree cousins (family 1) from Turkey; she was born at term after an uncomplicated pregnancy. Myoclonic seizures occurred within the first months and responded poorly to treatment. At the age of 7 months, a global developmental delay and severe muscular hypotonia with reduced spontaneous movements were noted. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her brain revealed delayed myelination and a small focal periventricular gliosis on the left side. Persistent focal myoclonic seizures, occurrence of generalized myoclonic-tonic seizures, and spasticity in all limbs led to a slow regression and loss of all achieved skills. Repeated MRI of her brain at the ages of 4 years and 12 years showed atrophy of the white matter. When we saw her at the age of 19 years, we saw a profoundly disabled young woman with poor interaction and without speech; she was wheelchair bound and fed by a gastric tube. X-rays of her spine revealed osteopenia and scoliosis (See case reports in Supplemental Data).

Her brother (P-2) was the third child of family 1 and was born at term after a normal pregnancy. At age 7 weeks, the first generalized seizure occurred, followed by a series of therapy-resistant frequent focal myoclonic seizures. He showed profound developmental delay, muscular hypotonia, and poor eye contact. Visual evoked cortical potentials (VECPs) were absent on the right eye and diminished on the left eye. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed an incomplete right bundle branch block (RBBB), and echocardiography showed an atrial septal defect (ASD) type II. At the age of 4 years, he had supraventricular tachycardia followed by further episodes requiring hospitalization and cardioversion. When we saw him at the age of 12 years, we saw a wheelchair-bound boy with profound intellectual disability, poor interaction, no speech, and severe scoliosis and who was fed by a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube.

P-3 is the first son of non-consanguineous healthy parents of European descent (family 2); he was born at 42 weeks of gestation after a normal pregnancy. He was hypotonic but without feeding problems. At the age of 11 months, he developed mainly myoclonic seizures and absences that were treated but not fully controlled. A brain MRI showed progressive cerebellar atrophy. At the age of 6 years, he showed a dysmetric movement disorder and profound developmental delay. Scoliosis was surgically corrected at the age of 17 years.

His brother (P-4) was born at term after a normal pregnancy. He was hypotonic. Brain MRI performed at the age of 4 months showed frontal atrophy and a Dandy Walker variant. His global development was profoundly delayed; he was able to speak two-to-three-word sentences and to walk a few steps at age of 5 years. At the age of 6 years, myoclonic epilepsy developed; this is now well controlled. An MRI done at this age showed progressive vermis hypoplasia. At his current age of 12 years, he is able to walk independently for short distances and to speak sentences of a few words. He has also developed scoliosis.

P-5 was the first daughter born to non-consanguineous healthy parents from Norway (family 3); she was born at 42 weeks of gestation after a normal pregnancy. She was hypotonic and had feeding problems. A brain MRI performed at the age of 10 months showed a thin corpus callosum and an enhanced ventricular system without signs of hydrocephalus. Her global development was profoundly delayed. Focal myoclonic seizures started at 3.5 years of age and were responding well to therapy. When we saw her at 5 years of age, she was a wheelchair-bound girl who spoke only few words and had impaired cortical vision. She was considered for a surgical correction of her scoliosis.

The individuals in this study were identified via the MatchmakerExchange platform10 using data that originated from the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany (family 1, P-1 and P-2), the Radboud University Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, (family 2, P-3 and P-4) and the Norwegian National Unit for Newborn Screening, Division of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Oslo, Norway (family 3, P-5). All samples were obtained after written informed consent was given by the guardians of the affected individuals. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki protocols and approved by the ethics committees of the respective institutions.

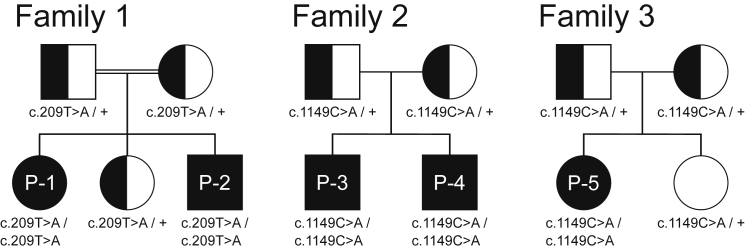

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) revealed two rare homozygous variants in PIGU (GenBank: NM_080476.4): c.209T>A (p.Ile70Lys), exon 3 in the two affected siblings (P-1 and P-2) of family 1, and c.1149C>A (p.Asn383Lys), exon 11 in families 2 and 3 (Figures 1 and 2A). Sanger sequencing confirmed biparental inheritance of the variants in all families; pedigrees and genotypes are shown in Figure 1. The variant c.209T>A (CADD score 25.9) has not been observed in gnomAD,11 while c.1149C>A (CADD score 26.5) has been observed only in a heterozygous state, in individuals from a European population, and with an allele frequency of 7/277194. Both variants were predicted to be pathogenic by MutationTaster,12 UMD Predictor,13 SIFT,14 and PolyPhen2.14 The exchange of the hydrophobic amino acid isoleucine at position 70 to a hydrophilic lysine was predicted to cause a conformational change of the first ER luminal domain between TM1 and TM2 (Grantham score 102). The exchange of the amino acid asparagine to lysine at position 383 is also positioned in an ER luminal domain before TM10 (Grantham score 94) (Figures 2B and 3C).

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of the Families 1, 2, and 3 with the Mutations in PIGU

The consanguineous parents from family 1 are of Turkish descent. Family 2 is from the Netherlands. Family 3 is from Norway.

Figure 2.

Position of Mutations in PIGU Gene and Protein

(A) Exon-intron structure and mutational landscape of PIGU.

(B) Conservation (black to gray shading) of PIGU protein sequence over multiple species and prediction of transmembrane (red arrows) domains.

(C) Transmembrane domain structure and location of missense variants in PIGU.

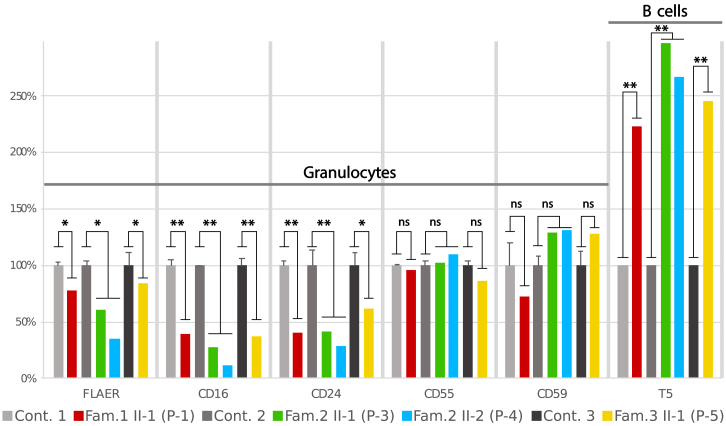

Figure 3.

Relative Cell Surface Expression of GPI-APs on Granulocytes and B Cells

On granulocytes of affected individuals (P-1, P-3, P-4, and P-5) a significant relative reduction of cell surface expression of FLEAR, CD16, and CD24 was observed compared to controls. But expression of CD55 and CD59 was not significantly altered on granulocytes. An increased expression of free GPI anchors was detected based on the presence of T5 antibody on B cells in affected individuals compared to controls. Values represent mean + SD. Error bars: n = 3 (parents and one healthy unrelated control), significance was verified by Student’s t-test, ns = not significant, ∗p<0.05, ∗∗p<0.01.

To assess the functional implications of the missense variants in PIGU for the GPI anchoring process, we performed flow cytometry on peripheral blood samples collected in CytoChex blood collection tubes (BCTs). For multicolor flow cytometry, cells were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies against GPI-APs (CD16, CD24, CD55, and CD59), as well as with fluorescein-labeled proaerolysin (FLAER), which binds to the GPI anchor itself. Use of the T5 4E10 antibody allowed detection of free GPI anchors.15, 16, 17, 18

Relative reduction of GPI-AP was calculated as a ratio of the staining index (SI) of an affected individual to the SIs of healthy parents and healthy unrelated controls. It is noteworthy that there were only subtle differences in GPI-AP staining between heterozygous carriers of pathogenic mutations (parents) and unrelated healthy controls.

As revealed by reduced expression of FLAER, the relative expression of GPI-APs CD16 and CD24 was significantly reduced on granulolcytes compared to controls. But CD55 expression was not significantly altered and CD59 expression was only slightly increased in three out of four individuals with mutations in PIGU compared to controls. (Figure 3). However, CD55 expression was not altered from that of controls, whereas CD59 expression was higher than that in controls in three out of four individuals with mutations in PIGU. This characteristic pattern of marker staining was observed in some individuals with mutations in PIGT, but this was not addressed by the authors.19, 20 The deficiency of the GPI transamidase in linking GPI-APs to the GPI anchor results in an abundance of free GPI on the cell surface. This can be assessed by the T5 antibody, which binds to the N-acetyl-galactoseamine side branch at the first mannose of the GPI anchor.16, 21 Compared to that of controls, the MFI for T5 of affected individuals’ B cells (for monocytes and granulocytes, data not shown) showed an increase of up to 3-fold (Figure 3). Thus, we conclude that the identified missense mutations in PIGU reduce the function of the GPI transamidase complex and lead to accumulation of free GPI anchor on the cell surface. Functional validation of the p.Asn383Lys variant was performed in a CHO cell line deficient for PIGU. Expression of GPI-APs was rescued less efficiently by transient expression of the p.Asn383Lys mutant than by wild-type PIGU (Figure S3).

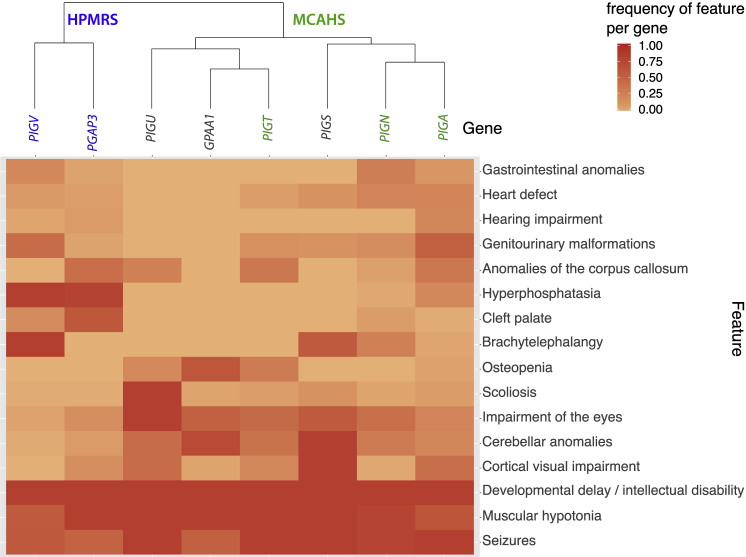

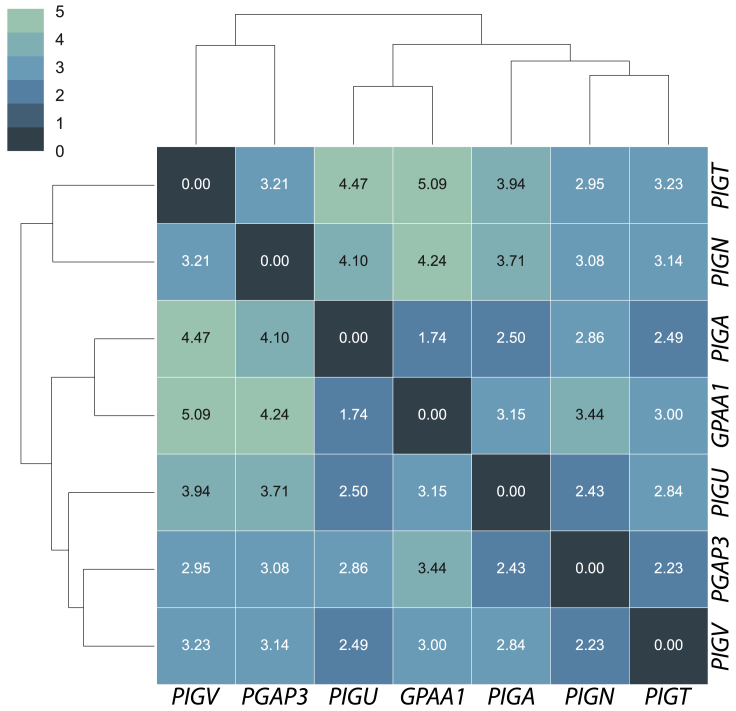

In order to analyze the phenotypic spectrum of the GPI transamidase deficiency and compare it to other GPIBDs, we conducted a systematic review of the phenotypic features of the most prevalent GPIBDs from the literature and additional cases with molecularly diagnosed GPIBDs (unpublished data). Therefore, we included individuals with mutations in PIGT (n = 26), GPAA1 (n = 10), PIGU (n = 5), and PIGS (n = 4, excluding two fetuses) for the GPI transamidase deficiencies; PIGV (n = 26) and PGAP3 (n = 28) for two types of hyperphosphatasia with mental retardation syndrome (HPMRS), HPMRS1 (MIM: 239300) and HPMRS3 (MIM: 615716), respectively; and PIGN (n = 30; MIM: 606097) and PIGA (n = 54; MIM: 311770) for two types of multiple congenital anomalies-hypotonia-seizures syndrome (MCAHS), MCAHS1 (MIM: 614080) and MCAHS3 (MIM: 300868), respectively. We grouped the reported clinical features of the cases in the following 16 feature classes: developmental delay and/or intellectual disability, muscular hypotonia, seizures, cerebellar anomalies (cerebellar hypoplasia, vermis hypoplasia, etc.), anomalies of the corpus callosum (CC)(including thin CC or hypoplasia of the CC), hearing impairment (including hearing loss), cortical visual impairment (including cortical blindness), impairment of the eyes (including strabism, nystagmus, and severe hyper- or myopia), cleft palate, genitourinary anomalies (including malformations of kidneys, urinary tract, or genitalia), heart defects (including ASD and patent ductus arteriosus), scoliosis, osteopenia (including osteoporosis), gastrointestinal anomalies (Hirschsprung disease and megacolon), brachyphalangy (including hypoplastic nails and short fingers or fingertips), and hyperphosphatasia. We counted the phenotypic features and divided by the number of cases that were assessed for each particular feature to determine the feature frequency per gene. The feature frequencies were plotted in a two-dimensional heatmap, and clustering was performed on the basis of Euclidian distance as a measure of similarity.

The feature analysis revealed a high similarity among individuals with mutated genes of the GPI transamidase complex (GPAA1, PIGT, and PIGU); their shared features were cerebellar anomalies, impairments of eyes, and osteopenia. However, osteopenia might be related to the inactivity of these severely disabled people. Scoliosis was identified in nearly all PIGU-deficient individuals and is probably a typical clinical feature of PIGU-associated GPIBD. So far, hearing impairment and hyperphosphatasia have not been described in individuals with GPI transamidase deficiency. Genitourinary malformations and heart defects without hyperphosphatasia and cleft palate were frequent in individuals with PIGT, PIGN, and PIGA mutations and are therefore considered characteristic for the MCAHS disease entity. Hypophosphatasia and cleft palate (together with brachyphalangy) were the most common features in individuals with PIGV and PGAP3 mutations, and these features represent the major symptoms in HPMRS. The dichotomy between the HPMRS and MCAHS characteristic phenotypic features is visualized in the two branches of the dendrogram in Figure 4. However, delineation of these disease entities based on the frequency of phenotypic features is challenging because of the broad phenotypic variability of MCAHS and also because elevated amounts of serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is not restricted to HPMRS. The major discriminatory features between HPMRS and other GPIBDs are increased levels of ALP in combination with cleft palate and brachytelephalangy. Genitourinary malformations were described in most individuals with PIGV deficiency, while anomalies of the corpus callosum were identified in most PGAP3-affected individuals. Except for in the case of brain anomalies, malformations were more prevalent in individuals with HPMRS than in individuals with the MCAHS spectrum, whereas in the latter group, a higher frequency of brain abnormalities has been documented. Cerebellar anomalies were frequent in all GPIBDs except HPMRS. All individuals with GPIBDs were affected by developmental delay and/or intellectual disability, muscular hypotonia, and seizures. A comparison of the phenotypic features of all diagnosed individuals with mutations in PIGU versus those of individuals with mutations in GPAA1, PIGT, and PIGS is presented in Table 1. More comprehensive clinical descriptions are listed in the Supplemental Data.

Figure 4.

Clustering and Heatmap of Feature Frequency per Gene

Genes of the HPMRS disease entity are highlighted in blue, MCAHS genes in green.

Table 1.

Comparison of the Clinical Features of Individuals with Mutations in PIGU versus Previously Reported Individuals with Mutations in PIGT, PIGS, and GPAA1

| PIGU P-1 | PIGU P-2 | PIGU P-3 | PIGU P-4 | PIGU P-5 | PIGT (n = 13)19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25 | PIGS (n = 6)7 | GPAA1 (n = 10)5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19 years | 12 years | 17 years | 12 years | 5 years | 11 months to 12 years | prenatal to 5.5 years | 4 to 30 years |

| Measurements | microcephaly | normal | Normal | normal | macrocephaly | microcephaly (2/9, 3 ND) | microcephaly (2/4, 2 ND) | short stature (5/10), microcephaly (1/10) |

| Alkaline phosphatase | normal | normal | Normal | normal | normal | low 8/13 | normal (6/6) | normal (10/10) |

| Developmental delay | profound | profound | Profound | severe | profound | profound (13/13) | yes (4/4, 2 ND) | mild to moderate (10/10) |

| Intellectual disability | profound | profound | Profound | severe | profound | profound (13/13) | yes (4/4, 2 ND) | mild to moderate (10/10) |

| Muscular hypotonia | yes | yes | Yes | yes | yes, severe | yes (13/13) | yes (4/4, 2 ND) | yes (10/10) |

| Spasticity | yes | yes | no | no | no | ND | no | yes (4/9, 1 ND) |

| Seizures | yes | yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes (13/13) | yes (4/4, 2 ND) | yes (7/10) |

| Cerebral atrophy | global | global | no | frontal | mild global | yes (9/11, 2 ND) | yes (2/4, 2 ND) | no |

| Cerebellar hypoplasia | progressive | no | progressive | progressive | no | yes (9/11) | yes (4/4, 2 ND) | yes (9/10) |

| Cortical blindness | yes | yes | no | no | yes | yes (9/9) | yes (3/4) | yes (1/10) |

| Strabismus | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes (9/9) | ND | ND |

| Nystagmus | no | no | no | no | yes | ND | yes (3/4) | yes (7/10) |

| Scoliosis | severe | severe | severe | yes | severe | yes (5/7) | yes (1/4) | mild (n = 1) |

| Osteopenia | yes | ND | ND | ND | ND | yes (7/9) | ND | yes (8/10) |

| other | slender bones | no | no | no | no | no | brachydactyly (4/6) | no |

“ND” indicates not documented.

A characteristic facial gestalt was observed for many individuals with GPIBDs. In a recent study, the facial features of individuals with GPIBDs were analyzed with FDNA’s DeepGestalt neural network.26, 27 However, the five individuals with PIGU mutations presented with only very subtle characteristic facial features. Therefore, we applied an approach with higher sensitivity and specificity to analyze genotype-phenotype correlations. Here, we used data from previously published cases5, 25, 26 as well as unpublished facial images of individuals with mutations in GPAA1, PIGA, PIGN, PGAP3, and PIGT to compare the facial gestalt to that of individuals with mutations in PIGU (n = 5). We chose PIGA (n = 25), PIGN (n = 15), PIGT (n = 13), PIGV (n = 24), and PGAP3 (n = 25) (unpublished data) as the most prevalent GPIBDs and we chose GPAA1 (n = 5) as another gene of the GPI transamidase complex. In total, 112 molecularly confirmed cases were processed. Informed consent was obtained from all families and was approved by the institutional review boards at the relevant institutions. Embeddings of facial images in a 128-dimensional space were calculated via a FaceNet-based approach.28 A pairwise distance comparison of the centroids of each gene cohort was then performed and clustered on the basis of Euclidian distances as the measure of similarity (Figure 5). In this approach, we achieved a gene-level classification accuracy of 62%, which is significantly better than random chance (1/7 = 14.3%).

Figure 5.

Pairwise Distances of Gene Centroids of Facial Image Embeddings from GPIBD Cases

The FaceNet-based image analysis of 112 molecularly diagnosed GPIBD cases achieved a gene-level classification accuracy of 62%.

As described previously by Knaus et al.,26 individuals with PGAP3 and PIGV mutations shared a characteristic facial gestalt and represented the HPMRS branch in the dendrogram (Figure 5). Also, individuals with MCAHS (PIGN, PIGA, and PIGT) shared facial similarities. As a result of shared facial similarities, the five individuals with PIGU mutations and the five with GPAA1 mutations formed a GPI transamidase branch in the dendrogram (Figure 5). It is notable that in our analysis, the facial gestalt of individuals with PIGT mutations shows a high level of dissimilarity to those individuals with PIGU (distance 2.49) and GPAA1 (3.00) mutations.

Discussion

Here, we describe a type of the autosomal-recessive GPIBD caused by bi-allelic mutations in PIGU. Deep phenotyping of the five affected individuals and of published cases with GPIBDs revealed shared phenotypic features in individuals with mutations in genes of the GPI transamidase complex. Impairment of the nervous system (cortical impairment of vision, cerebellar anomalies, and anomalies of the corpus callosum) with severe motor delay and associated skeletal anomalies (scoliosis and osteopenia) were characteristic in people with GPI transamidase deficiency. Intellectual disability or developmental delay, muscular hypotonia, and seizures are shared features among all individuals with GPIBD.

Computer-assisted facial analysis supported our assumption of facial similarities among individuals with GPI transamidase deficiency (with mutations in PIGU and GPAA1), individuals with HPMRS (with mutations in PIGV and PGAP3), and individuals with MCAHS (with mutations in PIGA, PIGN, and PIGT). We show that the effectiveness of computer-assisted gestalt analysis has a high potential to draw conclusions on the disturbed gene or protein complex in individuals with GPIBDs and probably beyond. We were able to achieve a better-than-random accuracy of 62% in predicting the affected gene in a pathway disorder solely from facial images, in spite of the unbalanced cohorts with few cases and different ethnic backgrounds. Computer-readable information contained in human face permitted classification of phenotypes into disease entities or syndrome families,26, 29, 30, 31 and this classification could in turn be used to predict affected genes or identify novel disease genes in known pathways.32 Moreover, the combination of computer-assisted facial analysis and deep phenotyping might not only be helpful in disease-gene identification but could also improve variant prediction in exome or genome data analysis.

The phenotypic features resulting from functional impairment of PIGU were corroborated by flow-cytometric analysis of GPI-AP expression and identification of free GPI anchors on the cell surfaces of blood cells. A biochemical discrimination of GPI transamidase deficiencies and other GPIBDs is possible through use of the T5 4E10 antibody.18 More importantly, in a functional workup of suspected GPIBDs, a multicolor flow cytometry panel is necessary in order to avoid missing potential GPIBD cases in which expression of several GPI markers is not reduced. Here, we define a multicolor flow cytometry panel (consisting of the GPI markers FLAER, CD16, CD24, CD55, CD59, and T5) to identify a characteristic profile of GPI marker expression in GPI transamidase deficiency. A more detailed and standardized analysis of GPI-AP expression of molecularly confirmed GPIBD cases might potentially identify more gene-specific or protein-complex-specific flow-cytometry profiles.

In conclusion, application of deep phenotyping in combination with computer-assisted facial analysis can support the diagnosis of suspected GPIBD cases where access to sequencing or flow cytometry is limited. Furthermore, this approach can help researchers to interpret variants of unknown clinical significance in GPIBD-associated genes. The identification of more individuals with GPIBDs and deep phenotyping thereof might facilitate prognostication of the condition on the basis of the mutated gene.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Berlin-Brandenburg Center for Regenerative Therapies (BCRT) (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, project number 0313911). We would like to thank Samuel C.C. Chiang and professor Yenan T. Bryceson at Center for Hematology and Regenerative Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge, Stockholm, Sweden for performing the initial flow-cytometry analysis with staining of GPI-linked cell-surface markers in whole blood for the proband P-5 in family 3.

Published: July 25, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Data can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.06.009.

Accession Numbers

The mutations in this report have been deposited at www.gene-talk.de and can be accessed at the following URLs: http://www.gene-talk.de/annotations/1371027 and http://www.gene-talk.de/annotations/1371028.

Web Resources

GeneTalk, http://www.gene-talk.de

Matchmaker Exchange, https://www.matchmakerexchange.org

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, https://www.omim.org

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Kinoshita T., Fujita M., Maeda Y. Biosynthesis, remodelling and functions of mammalian GPI-anchored proteins: Recent progress. J. Biochem. 2008;144:287–294. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvn090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinoshita T. Biosynthesis and deficiencies of glycosylphosphatidylinositol. Proc. Jpn. Acad., Ser. B, Phys. Biol. Sci. 2014;90:130–143. doi: 10.2183/pjab.90.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenhaber B., Sinha S., Wong W.-C., Eisenhaber F. Function of a membrane-embedded domain evolutionarily multiplied in the GPI lipid anchor pathway proteins PIG-B, PIG-M, PIG-U, PIG-W, PIG-V, and PIG-Z. Cell Cycle. 2018;17:874–880. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2018.1456294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong Y., Ohishi K., Kang J.Y., Tanaka S., Inoue N., Nishimura J., Maeda Y., Kinoshita T. Human PIG-U and yeast Cdc91p are the fifth subunit of GPI transamidase that attaches GPI-anchors to proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:1780–1789. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen T.T.M., Murakami Y., Sheridan E., Ehresmann S., Rousseau J., St-Denis A., Chai G., Ajeawung N.F., Fairbrother L., Reimschisel T. Mutations in GPAA1, encoding a GPI transamidase complex protein, cause developmental delay, epilepsy, cerebellar atrophy, and osteopenia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;101:856–865. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kvarnung M., Nilsson D., Lindstrand A., Korenke G.C., Chiang S.C., Blennow E., Bergmann M., Stödberg T., Mäkitie O., Anderlid B.M. A novel intellectual disability syndrome caused by GPI anchor deficiency due to homozygous mutations in PIGT. J. Med. Genet. 2013;50:521–528. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen T.T.M., Murakami Y., Wigby K.M., Baratang N.V., Rousseau J., St-Denis A., Rosenfeld J.A., Laniewski S.C., Jones J., Iglesias A.D. Mutations in PIGS, encoding a GPI transamidase, cause a neurological syndrome ranging from fetal akinesia to epileptic encephalopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;103:602–611. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng B.G., Freeze H.H. Human genetic disorders involving glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors and glycosphingolipids (GSL) J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2015;38:171–178. doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9752-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaeken J., Péanne R. What is new in CDG? J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2017;40:569–586. doi: 10.1007/s10545-017-0050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobreira N.L.M., Arachchi H., Buske O.J., Chong J.X., Hutton B., Foreman J., Schiettecatte F., Groza T., Jacobsen J.O.B., Haendel M.A., Matchmaker Exchange Consortium Matchmaker Exchange. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2017;95:1–, 15. doi: 10.1002/cphg.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lek M., Karczewski K.J., Minikel E.V., Samocha K.E., Banks E., Fennell T., O’Donnell-Luria A.H., Ware J.S., Hill A.J., Cummings B.B., Exome Aggregation Consortium Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarz J.M., Cooper D.N., Schuelke M., Seelow D. MutationTaster2: Mutation prediction for the deep-sequencing age. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:361–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., Salzberg S.L. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M.X., Kwan J.S., Bao S.Y., Yang W., Ho S.L., Song Y.Q., Sham P.C. Predicting mendelian disease-causing non-synonymous single nucleotide variants in exome sequencing studies. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azzouz N., Shams-Eldin H., Niehus S., Debierre-Grockiego F., Bieker U., Schmidt J., Mercier C., Delauw M.F., Dubremetz J.F., Smith T.K., Schwarz R.T. Toxoplasma gondii grown in human cells uses GalNAc-containing glycosylphosphatidylinositol precursors to anchor surface antigens while the immunogenic Glc-GalNAc-containing precursors remain free at the parasite cell surface. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2006;38:1914–1925. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirata T., Mishra S.K., Nakamura S., Saito K., Motooka D., Takada Y., Kanzawa N., Murakami Y., Maeda Y., Fujita M. Identification of a Golgi GPI-N-acetylgalactosamine transferase with tandem transmembrane regions in the catalytic domain. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:405. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02799-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Striepen B., Tomavo S., Dubremetz J.F., Schwarz R.T. Identification and characterisation of glycosyl-inositolphospholipids in Toxoplasma gondii. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1992;20:296S. doi: 10.1042/bst020296s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y., Hirata T., Maeda Y., Murakami Y., Fujita M., Kinoshita T. Free, unlinked glycosylphosphatidylinositols on mammalian cell surfaces revisited. J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:5038–5049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakashima M., Kashii H., Murakami Y., Kato M., Tsurusaki Y., Miyake N., Kubota M., Kinoshita T., Saitsu H., Matsumoto N. Novel compound heterozygous PIGT mutations caused multiple congenital anomalies-hypotonia-seizures syndrome 3. Neurogenetics. 2014;15:193–200. doi: 10.1007/s10048-014-0408-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam C., Golas G.A., Davids M., Huizing M., Kane M.S., Krasnewich D.M., Malicdan M.C.V., Adams D.R., Markello T.C., Zein W.M. Expanding the clinical and molecular characteristics of PIGT-CDG, a disorder of glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2015;115:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomavo S., Couvreur G., Leriche M.A., Sadak A., Achbarou A., Fortier B., Dubremetz J.F. Immunolocalization and characterization of the low molecular weight antigen (4-5 kDa) of Toxoplasma gondii that elicits an early IgM response upon primary infection. Parasitology. 1994;108:139–145. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000068220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pagnamenta A.T., Murakami Y., Taylor J.M., Anzilotti C., Howard M.F., Miller V., Johnson D.S., Tadros S., Mansour S., Temple I.K., DDD Study Analysis of exome data for 4293 trios suggests GPI-anchor biogenesis defects are a rare cause of developmental disorders. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;25:669–679. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2017.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawamoto M., Murakami Y., Kinoshita T., Kohara N. Recurrent aseptic meningitis with PIGT mutations: A novel pathogenesis of recurrent meningitis successfully treated by eculizumab. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-225910. bcr-2018-225910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang L., Peng J., Yin X.-M., Pang N., Chen C., Wu T.H., Zou X.M., Yin F. Homozygous PIGT mutation lead to multiple congenital anomalies-hypotonia seizures syndrome 3. Front. Genet. 2018;9:153. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bayat A., Knaus A., Juul A.W., Dukic D., Gardella E., Charzewska A., Clement E., Hjalgrim H., Hoffman-Zacharska D., Horn D., DDD Study Group PIGT-CDG, a disorder of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor: Description of 13 novel patients and expansion of the clinical characteristics. Genet. Med. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0512-3. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knaus A., Pantel J.T., Pendziwiat M., Hajjir N., Zhao M., Hsieh T.C., Schubach M., Gurovich Y., Fleischer N., Jäger M. Characterization of glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis defects by clinical features, flow cytometry, and automated image analysis. Genome Med. 2018;10:3. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0510-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gurovich Y., Hanani Y., Bar O., Nadav G., Fleischer N., Gelbman D., Basel-Salmon L., Krawitz P.M., Kamphausen S.B., Zenker M. Identifying facial phenotypes of genetic disorders using deep learning. Nat. Med. 2019;25:60–64. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroff F., Kalenichenko D., Philbin J. FaceNet: A unified embedding for face recognition and clustering. arXiv. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pantel J.T., Zhao M., Mensah M.A., Hajjir N., Hsieh T.-C., Hanani Y., Fleischer N., Kamphans T., Mundlos S., Gurovich Y., Krawitz P.M. Advances in computer-assisted syndrome recognition and differentiation in a set of metabolic disorders. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2018;41:533–539. doi: 10.1007/s10545-018-0174-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reijnders M.R.F., Janowski R., Alvi M., Self J.E., van Essen T.J., Vreeburg M., Rouhl R.P.W., Stevens S.J.C., Stegmann A.P.A., Schieving J. PURA syndrome: Clinical delineation and genotype-phenotype study in 32 individuals with review of published literature. J. Med. Genet. 2018;55:104–113. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferry Q., Steinberg J., Webber C., FitzPatrick D.R., Ponting C.P., Zisserman A., Nellåker C. Diagnostically relevant facial gestalt information from ordinary photos. eLife. 2014;3:e02020. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunner H.G., van Driel M.A. From syndrome families to functional genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:545–551. doi: 10.1038/nrg1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.