Abstract

In this article, we consider the role of heterogeneous nucleation in β‐amyloid aggregation. Heterogeneous nucleation is more common and occurs at lower levels of supersaturation than homogeneous nucleation. The nucleation period is also the stage at which most of the polymorphism of amyloids arises, this being one of the defining features of amyloids. We focus on several well‐known heterogeneous nucleators of β‐amyloid, including lipid surfaces, especially those enriched in gangliosides and cholesterol, and divalent metal ions. These two broad classes of nucleators affect β‐amyloid particularly in light of the amphiphilicity of these peptides: the N‐terminal region, which is largely polar and charged, contains the metal binding site, whereas the C‐terminal region is aliphatic and is important in lipid binding. Notably, these two classes of nucleators can interact cooperatively, aggregation begetting greater aggregation.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, amyloid‐β (Aβ) aggregation, cholesterol, gangliosides, heterogeneous nucleation, lipids, metal ions

1. NUCLEATION—HOMOGENEOUS AND HETEROGENEOUS

Classical nucleation theory concerns the formation of a new phase, for example, condensation of a vapor, freezing of a liquid, or precipitation of a solute from a solution. The last of these is exemplified by protein crystallization and fibrillization. Proteins readily form supersaturated solutions, that is, metastable ones, in which the concentration of the dissolved protein exceeds the solubility limit, but the solution cannot relax to equilibrium. Formation of a new (e.g., solid) phase occurs through nucleation, in which a small number of molecules become arranged in a pattern like that of the eventual solid. The nucleus forms a site upon which more molecules add as the crystal or fibril grows. The rates at which crystallization and fibrillization occur vary by many orders of magnitude. This theory, despite some limitations, has helped to explain this immense variation.

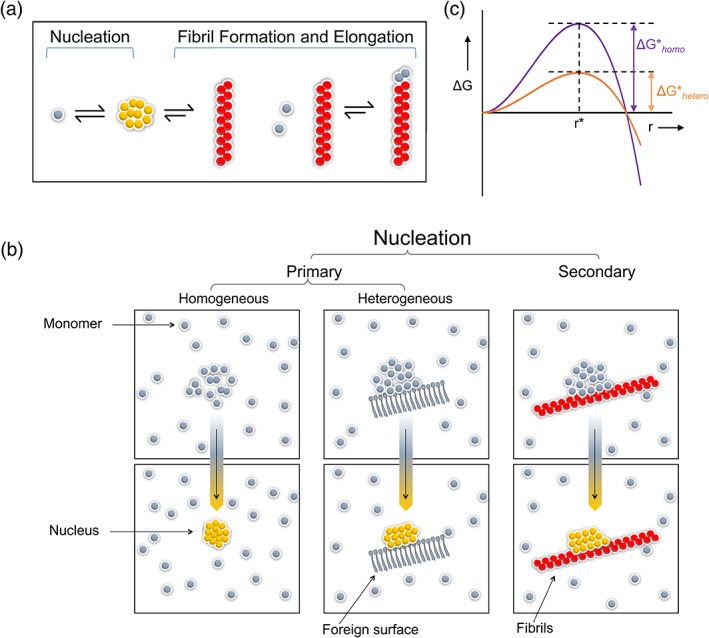

Nucleation can be divided into homogeneous and heterogeneous types (Figure 1). In homogeneous nucleation, nuclei form from only those molecules that eventually form the crystal or fibril—that is, monomers at supersaturating concentration. Heterogeneous nucleation is more common than homogeneous nucleation: a molecule of a different type acts as a surface to which the crystalizing or fibrillizing molecule adds. These molecules thus become oriented such that the growth of the crystal or fibril continues. A mote of dust falling into a supersaturated solution, leading to rapid crystal formation; a string put into concentrated sugar to make rock candy; scratching the glass of a beaker to induce crystallization are common examples of heterogeneous nucleation.

Figure 1.

Homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation. (a) In nucleation (for crystallization or fibrillization), the rate limiting step is the formation of a multimolecular nucleus, defined as the smallest aggregate for which the free energy for adding subunits (leading to formation of the crystal or fibril) is lower than that of losing subunits (leading to dissolution). This process is thermodynamically distinct from fibril growth (or elongation). (b) In homogeneous nucleation, the nucleus is composed of only aggregating molecules. Heterogeneous nucleation occurs on a foreign surface. (c) As described in the text, heterogeneous nucleation is generally energetically more favorable than homogeneous nucleation and thus is more common

It is clear why heterogeneous nucleation is more common than homogeneous nucleation (Figure 1b). According to the classical theory, in homogeneous nucleation, nuclei form at a rate that is the product of two factors: (a) the number of nucleation sites and (b) the probability that a nucleus of critical size has grown around it. The rate of formation of nuclei (R, in events per volume and per time) is given by:

where N S is the number of nucleation sites, Z is a proportionality constant, the Zeldovich factor (with features of a probability term), j is the rate of attachment of molecules to one another in the nucleus, ΔG ‡ is the free energy barrier for forming a nucleus, k B is the Boltzmann constant, and T is absolute temperature (Figure 1c).

The size of the free energy barrier to forming a new phase, however, is much lower in heterogeneous than homogeneous nucleation. This can be demonstrated for the relatively simple case of the formation of a droplet from vapor. In the absence of surface tension, the free energy change, ΔG, for the formation of the droplet would be the free energy of transferring n moles from the vapor at pressure, P, to the liquid phase at pressure, P 0. But because the droplet possesses surface energy (given by 4πr2 γ, where γ is the surface tension), ΔG is actually:

In homogeneous nucleation, the relevant surface area is the entire area of the (spherical, in the simplest case) nucleus. In heterogeneous nucleation, however, the exposed surface area is smaller, as part of the surface is occupied by the heterogeneous surface on which nucleation is occurring. Furthermore, when a liquid is able to wet a surface and spread on it (i.e., decrease in contact angle), the effective surface energy is decreased, thereby lowering the free energy barrier for nucleation.

Heterogeneous nucleation and the related phenomenon of surface catalysis represent special cases of the more general attributes of catalysts. This applies, alike, to β‐amyloid (Aβ) and other fibril‐forming peptides, such as α‐synuclein1, 2 and islet amyloid polypeptide.3, 4 Catalysts act by mechanisms that can be readily appreciated in surface catalysis: that is, they act by the effects of concentration of reactants, proximity of reactants, proper orientation of reactants, and propinquity of reactants.5, 6 Or put another way, surfaces catalyze by an entropic effect of reducing the search for reactants to two, rather than three dimensions.

2. FIBRILLIZATION OF Aβ PEPTIDES AND HETEROGENEOUS NUCLEATION

Fibril formation is divided thermodynamically into separable nucleation and growth phases.7, 8 The nucleation phase corresponds to the commonly observed lag phase in fibrillization assays (e.g., thioflavin T fluorescence, sedimentation). After nucleation, relatively rapid fibril extension (elongation or growth) occurs, probably through addition of monomers.9 An additional important phenomenon in fibril growth is secondary nucleation (which could also have been considered as a special example of heterogeneous nucleation). In secondary nucleation, new nucleation sites arise on preexisting aggregates made of the same type of monomeric units (e.g., Aβ molecules).10 Though clearly important in the overall kinetics of fibrillization, we will not discuss this further as this occurs after a fibril has already formed. The aggregation of Aβ peptides is quite complex, but we confine ourselves to one particular aspect of it: the possibility of heterogeneous nucleation as a factor catalyzing soluble oligomer and fibril formation. The concentration of Aβ in the cerebrospinal fluid is estimated to be about 10 ng/mL.11, 12, 13, 14 In one well‐controlled study,15 for example, mean Aβ42 concentrations in patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD) were 1.06 ± 0.25 ng/mL (slightly lower than normal subjects at 1.49 ± 0.59 ng/mL), whereas mean Aβ40 were 6.36 ± 3.07 ng/mL (not statistically different from normal subjects, mean 5.88 ± 3.03 ng/mL). Of course, local concentrations of Aβ peptides are likely higher than this level, but the question remains whether they can ever attain sufficiently high levels for spontaneous aggregation by homogeneous primary nucleation. Such concentrations are easily achieved in vitro but are several orders of magnitude higher than Aβ concentrations that have been reported in the brain. Even if such concentrations are at times attained in vivo (e.g., after brain trauma),16, 17, 18 the localized deposition of Aβ suggests a role for heterogeneous nucleation of Aβ in AD and the related clinical entity, cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Several point mutations within the Aβ peptide sequence19, 20, 21 are associated mainly with the occurrence of CAA rather than neuritic plaques. In the case of other point mutant forms of Aβ, neuritic plaques occur in brain parenchyma in typical early onset AD, rather than in blood vessels.22 In these instances, there appears to be a tropism for deposition of peptide within either cerebral blood vessels or brain parenchyma, despite comparable concentrations of Aβ peptides. Note, however, that even the relatively high ambient Aβ concentrations observed in people with Aβ point mutations are still orders of magnitude lower than those used for assays of homogeneous fibrillization in vitro. One possible explanation of the AD/CAA divide is that extrinsic factors within the brain—in parenchyma or blood vessels—contribute sites of heterogeneous nucleation. In cases of point mutations of Aβ associated with CAA, the mutant peptides might have a propensity to nucleate heterogeneously on a blood vessel macromolecule.

It has been well documented that the rate of Aβ aggregation is increased by a wide variety of extrinsic substances. Solid surfaces such as mica, Teflon, graphite, and gold increase the rate of aggregation.23, 24, 25 In these instances, the protein concentration required for aggregation is orders of magnitude lower than required for homogeneous nucleation of fibril growth.26 Inasmuch as these examples represent catalysis of fibril formation, rather than an alteration of the fibril structure, like any catalysis, there would be no alteration of the final equilibrium state of the reaction, only an alteration of the rate at which the reaction occurs. It is also possible, however, that some or all of these extrinsic substances affect the structure of the fibril and hence the position of the final equilibrium. In that case, not only would heterogeneous nucleation be occurring, but in addition, the products of reaction would be different from those formed homogeneously. Indeed, this too has been well documented, as these same extrinsic substances also influence fibril structure. One of the defining features of amyloids is polymorphism, and it has been shown that most of this polymorphism arises during the nucleation of the fibrillization reaction.27, 28, 29 Different forms of fibrils and/or soluble oligomers (precursors of fibrils) may have different degrees of neurotoxicity or interact differently with diagnostic or therapeutic reagents (e.g., antibodies).30, 31, 32 For these reasons, the identification of biologically relevant heterogeneous nucleators is a point of potentially great importance.

For the remainder of this article, we will consider several heterogeneous nucleators of potential biological relevance, bearing in mind that the effects of these nucleators are not necessarily only catalytic. These nucleators include: (a) lipid surfaces such as those of biological membranes especially, (b) gangliosides in combination with cholesterol; (c) metal ions, especially divalent and trivalent metal ions; and (d) sugars, especially complex glycans in extracellular matrix and on cell surfaces (not further discussed in detail in this article).

3. EFFECTS OF LIPID SURFACES AND OTHER AMPHIPHILIC OR HYDROPHOBIC INTERFACES ON Aβ AGGREGATION

Aβ peptides are produced by successive proteolytic cleavage of the membrane glycoprotein, amyloid precursor protein (APP). Initial cleavage by β‐secretase, followed by γ‐secretase, leads to production of peptides of approximately 38–43 amino acids, of which the most abundant in neuritic plaques are Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42).33, 34 Aβ peptides are amphiphilic, a fact that is readily predictable from amino acid sequence (Figure 2a). The C‐terminal approximately 10–12 amino acids (starting approximately at Ala30) are aliphatic, while the N‐terminal domain contains many charged and polar residues. There is, in addition, a second hydrophobic stretch, residues 17–21, which has been called the juxtamembranous domain of APP and may associate with the acyl chains of the membrane phospholipids.36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 The two hydrophobic domains constitute most of the two β‐sheets found in many fibril structures.41, 42 Beyond these obvious properties of the sequence, the amphiphilicity of Aβ peptides has been demonstrated experimentally. Aβ(1–40), and presumably other Aβ peptides, readily form stable monolayers at the air–water interface, the most common experimental model for the oil–water interface.44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 The amphiphilicity of Aβ is itself a cause of its self‐association. Several authors have noted the micelle‐like nature of some Aβ soluble oligomers,50, 51, 52, 53, 54 and in fibrils, the parallel, in‐register nature of the β‐sheets tends to minimize the exposure of the hydrophobic domains to the aqueous medium. In addition, it has been shown that a short internal fragment of Aβ, Aβ16‐21, forms antiparallel β‐sheets when the N‐terminus is acetylated, but the orientation flips to parallel and in‐register when the N‐terminus is octanoylated—a change that also renders the peptide more amphiphilic in monolayers at the air–water interface.

Figure 2.

The amphiphilicity of Aβ peptides. (a) Sequence of human Aβ (Aβ42 is shown), color‐coded. (Hydrophobic residues are yellow; charged/polar residues are red, blue, green for acidic, basic, uncharged, respectively. Hydrophobicity scales differ: Tyr is considered here as hydrophobic; His is considered as polar and uncharged, though obviously it bears partial positive charge at near neutral pH; and Gly residues are depicted in black). The hydrophobic (or lipophilic) residues form two clusters, residues 17–21 and 30–42, which eventually form most of the two β‐sheet segments in fibrils. (b) Formation of Aβ aggregates on “ganglioside nanoclusters” was from mouse neuronal lipids, including mainly gangliosides, sphingomyelin (SM), and cholesterol. Morphology of these aggregates depended strongly on lipid composition. Reprinted from Reference 35

As a consequence of its amphiphilicity, Aβ peptides bind to lipid surfaces, membrane, and solid surfaces.55 Among the hydrophobic surfaces that appear to nucleate Aβ aggregation and fibrillization are Teflon and graphite. (Mica, a flat silicate with a negative surface charge, also catalyzes Aβ aggregation, though by different mechanisms, as mentioned above.) These materials resemble the interior of biological membranes, for example, the acyl chains of membrane phospholipids. Aβ peptides also bind to amphiphilic surfaces such as phospholipids (egg phosphatidylcholine) and thin, amphiphilic block copolymer films (e.g., polystyrene‐block‐poly(2‐hydroxyethyl methacrylate).56 In these studies, adsorbed peptides were constrained to diffusion within two dimensions, which altered (in some cases, even lowered) rates of fibrillization. These are, in effect, entropic effects, because limiting the diffusion of Aβ(1–42) molecules to two dimensions favored their eventual aggregation into fibrils at concentrations that are orders of magnitude lower than the critical concentration for fibrillization in bulk solution.

A number of other studies, using biophysical techniques such as FRET and quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring,57 indicate that Aβ peptides bind to and aggregate on lipid surfaces. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, N‐terminal charged residues play an important role in the early stages of adsorption. Adsorption alters the flexibility and viscoelastic properties of the bound peptides. Aβ peptides, like other amyloid forming peptides and proteins, also interact with micelle‐forming surfactants such as sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and various other neutral, zwitterionic, and anion surfactants.58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 In addition, Aβ peptide aggregation is fostered by certain “membrane‐mimetic” solvents such as 2,2,2‐trifluoroethanol (TFE) and hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP).64, 65 In such environments as lipid or detergent micelles, and membrane‐mimetic solvents, Aβ peptides may assemble into soluble oligomers that can function as pores.66 There is, however, a great deal of still partially understood complexity in the interaction between Aβ peptides and lipids. For example, it has been shown that Aβ(1–42) adsorbs to and forms fibrils on small unilamellar vesicles at all 1‐palmitoyl‐2‐oleoyl‐sn‐glycero‐3‐phosphocholine (POPC) concentrations used in one study.67 Polymorphic fibril formation was demonstrated by variations in lag time, elongation rate, maximum thioflavin T (ThT) intensity, and fibrillar morphology. With large unilamellar vesicles, however, low POPC concentrations did not affect fibrillization kinetics markedly, but at higher POPC concentration, this lipid suppressed fibril formation. Thus, aggregation kinetics and the structure of the fibrillar products depend not only on lipid composition but also on physical factors such as radius of curvature of the surface.68, 69, 70

In line with the above studies, it has been shown that the effects of membranes on Aβ aggregation are modulated by variations in membrane fluidity. The main regulator of mammalian membrane fluidity is cholesterol.71, 72 Cholesterol plays a major role in production of Aβ peptides, through its effects on the cleavage of APP by both β‐secretase73 and γ‐secretase.38, 74, 75 In addition to this effect, cholesterol modulates the aggregation of Aβ peptides in a more direct manner. Using in situ scanning probe microscopy performed on planar bilayers (of whole brain lipid), a correlation was observed between membrane fluidity and membrane insertion and fibrillization of Aβ peptides.76 Whole brain lipid, however, does not necessarily reflect membrane lipid composition alone.

More recently, DMPC:cholesterol vesicles were shown to accelerate Aβ(1–42) aggregation by accelerating the rate of Aβ(1–42) primary nucleation by up to 20‐fold.77 Through a detailed analysis of kinetics, this effect was shown, in particular, for the heterogeneous nucleation of Aβ(1–42) oligomers.77 Furthermore, because this interaction is a cooperative one, in which multiple cholesterol molecules interact with Aβ(1–42), these results could help rationalize the association between aggregation of Aβ(1–42) and impaired cholesterol metabolism.78

4. THE ROLE OF GANGLIOSIDES IN COMBINATION WITH CHOLESTEROL

Like cholesterol alone, gangliosides alone or in combination with other lipids, also have been reported to enhance Aβ aggregation.76 Gangliosides are a minor portion of total membrane lipid—approximately 1–2% (or in some reports, higher) in the outer bilayer leaflet of the plasma membrane in the nervous system79, 80, 81—but can associate with sphingomyelin (SM) and cholesterol forming “lipid rafts.”82 Although the status of lipid rafts is somewhat controversial,83, 84 they may constitute a microdomain that acts as a key site for the onset of Aβ aggregation. Many of the studies on interaction of Aβ peptides with gangliosides focus on GM1.35 GM1 has a large and anionic head group. Because of the large head group, it has a low percolation threshold (calculated to be ~22 mol%85; that is, at mol% ≥ 22, GM1 forms a network essentially blanketing the membrane leaflet). At lower (physiological) mol%, GM1 forms clusters and ordered microphases of various types, such as rafts (liquid‐ordered phase ≥1 mol% of GM1) and nanoclusters (less ordered and more dynamic than rafts) in combination with SM and cholesterol.86, 87 Using ultrastructural methods, and later, using radiolabeled and biotin‐labeled GM1, it was shown that this ganglioside (and perhaps others) also accumulates in caveolae and in endosomes of certain cancer cell lines.88, 89

The anionic nature of gangliosides depends in part on the number of sialic acid residues in a particular subclass of these lipids. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have suggested that binding of Aβ peptides to GM1 depends on ionic interactions between side chains (e.g., K28) of Aβ and sialic acid residues.90 (In addition, this study posited a role for π‐π interactions between GM1 and aromatic side chains of Aβ). Furthermore, the role of GM1 head groups in the interaction with Aβ is also suggested by studies showing that model lyso‐GM1 micelles and liberated pentasaccharides have quite similar interactions with Aβ peptides as the full lipid with two acyl chains.91, 92, 93, 94

Early studies hypothesized and reported a ganglioside‐bound Aβ complex (G:Aβ), which can act as an endogenous seed for Aβ aggregation at neuronal membranes.95, 96 Many of these studies focused on gangliosides within “lipid rafts” and artificial lipid surfaces such as phospholipid bilayers (vesicles) containing high (~20 mol%) mole fractions of ganglioside.95, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101 Notably, Aβ binds ganglioside‐rich domains only when these are clustered in the membrane, in which case they are usually clustered with cholesterol and SM as well.102 Under conditions where gangliosides are homogeneously distributed in the membrane, they do not act as effective niduses for Aβ aggregation. Molecular dynamics simulations also support the idea that these clusters are formed when the ganglioside, GM1, is mixed with cholesterol and SM, but not when it is mixed with phosphatidylcholine.103 Thus, gangliosides act as part of a cluster of lipids, with a particular microenvironment.

The literature reports various effects of GM1 and associated lipids on Aβ aggregation and the structure of aggregates. These variations seem to depend on the specific combinations and concentrations of lipids used, and on the methods used to study Aβ aggregation. For example, CD104 and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR)105 spectroscopy indicated a conformational transition from α‐helix to β‐sheet, but these studies used raft‐like lipid surfaces (e.g., GM1: cholesterol: SM = 4:3:3104). In the former study, at intermediate Aβ/GM1 ratios (0.013–0.044), an α‐helical form coexisted with the β‐sheet form of Aβ, and the β‐sheet aggregates remained stable, without growth into fibrils. As the proportion of Aβ increased (Aβ:GM1 ratio > 0.044), the aggregates recruited Aβ monomers from solution and thus seeded fibril growth. In another study, the binding and aggregation of Aβ(1–40) to lysoganglioside GM1 micelles was also demonstrated by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) line broadening and dynamic light scattering, and this binding was irreversible.91 And in yet a different study, conducted using lower GM1 mol%, one group reported that SM triggers oligomerization of Aβ40, while GM1 prevents it. Various other studies using NMR,68, 91, 92 CD and FTIR,53, 106 and Raman107 spectroscopy also have suggested an α‐helix to β‐sheet transition, though comparison across studies is not always possible. Such studies underscore the complexity of these interactions, which still awaits clarification.108

There have been only limited studies on the structure of fibrils formed on a ganglioside substratum, but most of these suggest that the fibrils thus formed have the parallel, in‐register β‐sheet structure of most mature amyloid fibrils. In one study, using ganglioside‐enriched, planar bilayers, (20:40:40 monolayers of GM1, SM, and cholesterol on POPC‐coated mica), AFM showed fibril formation, and FTIR reflection–absorption spectroscopy suggested parallel β‐sheet structure.105 Fibrils formed in the absence of these lipids had FTIR spectra suggestive of antiparallel β‐sheet structure, though these results need to be interpreted cautiously, because FTIR has previously suggested antiparallel β‐sheet structure when higher resolution and more detailed solid‐state NMR ultimately proved parallel β‐sheet structure.109

An important remaining question in these studies is the nature of the interaction between Aβ peptide and gangliosides such as GM1. One can envision two broad categories of interactions between Aβ and GM1 and thus ask about their relative importance. There might be interactions between polar amino acids side chains, mainly in the N‐terminal region of Aβ, which interact with the head groups of GM1. There might also be interactions between the hydrophobic C‐terminal domain of Aβ and the second hydrophobic domain at residues 17–21 and the acyl chains of GM1. Obviously, these two types of interactions are not mutually exclusive. One important study used paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) NMR and molecular dynamics simulations to develop a model of the interaction of the carbohydrate moieties of GM1 with Aβ.110 They showed that the Gal and Neu5Ac residues of GM1 had the largest perturbations in PRE experiments, which was also in accord with their MD simulations and also with studies from other investigators111, 112 of proteins known to bind to GM1 (cholera toxin secreted by Vibrio cholerae, and VP1 capsid protein from SV40, respectively). In a similar vein, an NMR study of Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–28) (and α‐synuclein, which also binds to GM1) showed, perhaps somewhat surprisingly, that it was primarily the N‐terminal half of these Aβ peptides that interacted with GM1 (peak broadening and attenuation).94 This result argues for the importance of interactions between the headgroups of GM1 and side chains of polar amino acids in Aβ peptides.

5. METAL IONS

Postmortem examination of patients with AD has shown that brains with many neuritic plaques also contain high concentrations (~0.5–1 mM) of metal ions,113 especially the divalent and trivalent ions, Zn2+, Cu2+, and Fe3+ compared with age‐matched controls.114, 115 High concentrations of Al3+ were also found in the core of the neuritic plaque,116, 117 though this result is difficult to assess because of the ubiquity of Al3+ contamination.118, 119, 120 Direct examination of plaques showed that these high metal concentrations (Zn2+ and Cu2+) were due to metal accumulation within the plaques themselves, that is, rather than an indirect effects of the plaques.121 More or less in parallel with these observations was the demonstration that the addition of Zn2+, Cu2+, and other metal ions to solutions of Aβ peptides greatly accelerated fibril formation, as will be discussed in more detail, below. A provocative hint about the role of metal ions in Aβ aggregation and AD pathology comes from the observation that certain rodent species might not develop AD pathology to as great an extent as humans at a species‐adjusted comparable age, though these results await confirmation122, 123, 124 (see also Kozin et al.125 and Talmard et al.126 below). As discussed below, rodent (mouse and rat) Aβ lacks one of the key residues for metal binding (R rather than H at position 13),39, 127 though His6 could assume this role in the absence of a His residue at position 13.

Research of the past two decades has led to a much improved understanding of the mechanisms of metal ion binding by Aβ peptides.114, 123, 125, 126, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153 There is a fundamental difference between the mechanism of metal ion binding by Aβ and that of the well‐structured metalloproteins.106 Aβ is an unstructured or disordered peptide; thus, it does not adopt a unique conformation (or a small number of unique conformations) that could coordinate a metal ion. Rather, Aβ binds metal ions such that the bound metal ions are in rapid equilibrium with metal ions free in solution. Furthermore, while metal ion binding by proteins is generally pH dependent, there is an especially steep pH dependency for the binding of metal ions by Aβ.154 Finally, because Aβ peptides form an ensemble of structures, metal ion binding by Aβ is exquisitely sensitive to other physical variables such as temperature, ionic strength, and other fibrillization conditions.

Structural studies have identified some of the metal binding motifs in Aβ (Figure 3, showing Zn2+ binding to wild‐type Aβ, and Aβ with the English mutation [H6R‐Aβ]155). A stable dimer of Aβ(1–16) binds Zn2+ through contributions of His14 and Glu11.156 Cu2+ is coordinated in a similar manner, by two of the three His residues (13 and 14) and Asp1 of Aβ, without involvement of His6. As noted, the polypeptide chain conformation around these two His residues is distinct from that found in the β‐sheet, where vicinal residues are on opposite sides of the peptide bond. Finally, a Zn2+ bridged dimer of rat Aβ, which lack His13, is formed through His14 and His6. The striking feature of these structures is the flexibility of Aβ. It can bind various metal ions; only Zn2+ and Cu2+ are shown, but one can readily envision binding of other divalent metal ions like Fe2+, or trivalent metal ions like Al3+ and Fe3+.

Figure 3.

Three structures of Aβ peptides binding metal ions. (a) Human‐Aβ1‐16 monomer (Zn2+); pdb 1ze9. This peptide, lacking the hydrophobic domains, does not form fibrils and can exist at higher concentrations in solution than full length Aβ peptides. Here, this peptide is shown as a monomer binding Zn2+. (b) Human‐Aβ(1‐16) dimer (Zn2+); pdb 2mgt. This same peptide, at different Aβ:Zn2+ ratios, forms a dimer bridged by a Zn2+ ion, the “English mutation” of Aβ (H6R).155 (c) Rat‐Aβ(1‐16) dimer (Zn2+); pdb 2li9. The rat Aβ(1‐16) peptide also binds Zn2+ and other metal ions, despite lacking the His13 residue of human Aβ

As discussed earlier, the basic phases of fibril formation are nucleation and fibril elongation or growth. In addition, once fibrils form, fragmentation, secondary nucleation, and fibril dissolution add greater complexity to the overall kinetics.153, 157, 158, 159 Metal could affect any of these stages, though in different ways.

Probably, the most important effect of metal ions on Aβ aggregation occurs at the stage of nucleation. Although high concentrations of many metal ions generally accelerate fibril formation,81 here, too, there is greater complexity than first meets the eye. One study comprehensively compared the effects of Cu2+, Zn2+, Fe3+, and Al3+, and showed distinct features of these metal ions. For example, three techniques (Bis‐ANS fluorescence, tyrosine fluorescence, and far‐UV CD spectroscopy) indicated that Al3+ and Zn2+ increased exposure of hydrophobic domains of Aβ(1–40), but Cu2+ decreased it.82 Under the conditions used in these studies, Zn2+ specifically promoted the formation of “annular protofibrils” (as detected by A11 antibody binding and transmission electron microscopy), whereas Cu2+ and Fe3+ inhibited fibril formation and prolonged the lag phase in ThT fluorescence assays. These results are somewhat in conflict with earlier studies showing acceleration of Aβ fibrillization by metal ions, but the critical difference is that the latter study used lower metal ion concentrations (e.g., 5–50 μM).

An additional complication in assessing the role of metal ions is that they can lead to the formation of so‐called amorphous aggregates and protofibrils, especially at high concentrations of metal ions and/or Aβ. Both in the context of metal ion binding by Aβ139, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164 and in other contexts, such as the inhibition of Aβ fibrillization by transthyretin,164 rapid aggregation of Aβ may lead to precipitation and the formation of solids without the structural regularity of a fibril as observed by transmission electron microscopy. It is not clear whether such amorphous aggregates truly represent a structurally distinct species from fibrils, rather than merely a more rapidly forming, polymorphous collection of small fibrils—that is, whether the difference between “fibrils” and “amorphous” aggregates is at the level of molecular structure (as observed by solid‐state NMR, for example) or kinetics. Some evidence indicates that the difference may be mainly a kinetic one, but that structural differences, albeit subtle ones, do exist between mature fibrils and “amorphous aggregates” or “protofibrils.” For example, one study found that Zn(II) and Cu(II) profoundly inhibited Aβ(1–42) fibrillization but led to rapid precipitation and formation of “non‐fibrillar” aggregates. Over time, or with the addition of metal ion chelators, however, the seemingly amorphous aggregates got converted into fibrils with the appearance of typical amyloid fibrils in transmission EM.165 Such results suggest that amorphous aggregates are not an end point in the aggregation process, but rather, an intermediate observable by techniques such as electron microscopy. Another study examined maturation of “protofibrils” to fibrils using solid‐state NMR.166 These authors examined an antibody (B10AP)‐stabilized Aβ(1–40) protofibril and found that the overall features of the protofibril were quite similar to those of the mature fibrils, but there were some differences. In general, mature fibrils and protofibrils have β‐strands in the same positions, but the β‐strands of mature fibrils “seem to recruit more residues” (in the authors' words). In protofibrils, for example, Glu11 and Val12 are not in β‐strands (as measured by secondary chemical shifts), while in mature fibrils, these residues extend the N‐terminal β‐strand segment.

Thus, metal ions could accelerate the formation of “amorphous aggregates” and “protofibrils,” and this might foster the eventual accumulation of amyloid, and yet, at the same time, binding of metal ions could trap Aβ into precursors of the final, mature fibril. One possible explanation for these effects lies in the positioning of the metal‐binding residues of Aβ, in particular, the positioning of the three His residues at positions 6, 13, and 14 (in human Aβ). In a β‐sheet structure, the side chains of His13 and His14 fall on opposite sides of the peptide backbone. When monomeric (and perhaps also small aggregates of Aβ) bind a metal ion, the side chains of the three His residues and a fourth site (such as the amino terminus) coordinate the ion. In such structures, the side chains of His13 and His14 are not on opposite sides of the peptide chain. Thus, the coordination of a metal ion could oppose conversion of the region around His13 and His14 into the β‐sheet conformation. Some studies suggest that His6, which is not part of a β‐sheet in most fibrils, also has a less pronounced effect on metal‐ion‐mediated fibril formation.167

Another mechanism by which metal ions contribute to Aβ aggregation, and perhaps even more so to Aβ cytotoxicity, is through their redox activities. Aβ peptides can reduce Cu2+ to Cu+, and to lesser extent Fe3+ to Fe2+. 168, 169 These redox reactions generate reactive oxygen species such as H2O2 and OH• radical by Fenton chemistry or a Haber–Weiss reaction.169, 170 The presence of redox‐inert Zn2+ attenuates this process.171 In some cases, the electrons that reduce redox‐active metal ions arise from side chains of the Aβ peptide (e.g., Met35),172 while in other cases, they may arise from biologically available reducing agents (e.g., dopamine and ascorbate).121 The sole Tyr residue of Aβ, Tyr10, then becomes susceptible to loss of a single electron, generating reactive tyrosine radicals, which leads to formation of covalently linked Aβ. Such dimers have been shown to occur in the brains of individuals dying with AD, in particular in insoluble material that could be solubilized into 6.8 M guanidine HCl, and these could lead to formation of higher oligomers and/or fibrils.173, 174

6. CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Aβ aggregates into fibrils, most of which have a parallel, in‐register β‐sheet structure, although some antiparallel β‐sheet fibrils, and oligomers, have been reported.26, 27, 28, 175 What the nucleators discussed above have in common is that they all tend to foster parallel, in‐register β‐sheet structure. Aβ is an amphiphilic peptide, and the nucleators discussed above break into those applying to the hydrophobic domains, and those applying to the polar/charged domains. These spatially separated polar and hydrophobic domains can both contribute to heterogeneous nucleation of Aβ aggregation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Because of the amphiphilicity of Aβ peptides, different modes of heterogeneous nucleation can work together and amplify one another. Metal ions lead to formation of Aβ dimers or oligomers (a), which also brings the hydrophobic C‐termini into proximity and concentrates them (b), leading to further aggregation. (c) Aβ peptides, whether metal‐bound or not, have hydrophobic C‐termini that can bind to lipid surfaces

At one end of Aβ peptides is a metal‐binding domain, which also contains both anionic and cationic amino acids, and other polar residues. Metal ions have various effects on Aβ aggregation, as discussed above, but to summarize, there are several ways that metal ions could affect Aβ nucleation: (a) Metal ions could induce a conformation that is more aggregation prone than monomeric Aβ. This would include the orientation effect mentioned at the start of this article: by orienting Aβ at the N‐termini (the metal ion binding domain), they also orient the hydrophobic domains. (b) The simultaneous orientation of N‐ and C‐termini is also a propinquity effect. (c) Divalent and trivalent metal ions allow for bridging, thereby concentrating Aβ molecules. Not only the metal ions but also the Aβ molecules are multivalent. The clusters of Aβ molecules thereby bridged through metal ions are theoretically infinite. (d) As discussed, redox activities of metal ions can also modify Aβ peptides covalently, thereby vastly stabilizing a dimer, as in the case of dityrosine dimers.169, 176

At the other end of Aβ peptides is the hydrophobic C‐terminal region. This section of the peptide and the other hydrophobic domain at residues 17–21 typically form the two β‐sheets in oligomers and fibrils. These segments are also well suited to interact with amphiphilic lipid surfaces. Amphiphilic lipid surfaces self‐assemble to minimize the exposure of acyl chains to the aqueous medium, to the extent possible given countervailing forces. Such compromise actions can nevertheless leave some part of hydrophobic surface exposed to water. To take the relatively simple example of POPC single bilayer vesicles, the packing geometry of vesicles represents a compromise minimizing the exposure of acyl chains to water to the extent possible given packing constraints of the POPC headgroups; nevertheless, some part of the acyl chains remains exposed to water, allowing for binding of amphiphilic peptides.177, 178, 179 Thus, lipid surfaces can accommodate the binding of Aβ, through amino acid side chains of two hydrophobic domains, residues 17–21, and residues 31–42. The latter domain is part of the transmembrane helix of APP, whereas the former is hypothesized as a juxtamembranous domain that can insert into the membrane bilayer.180

Finally, GM1 ganglioside and cholesterol form a special type of lipid surface. These two lipids are often associated with one another, and with SM in specialized membrane microdomains, typified by, but not limited to lipid rafts. High mole percentages of GM1 favor binding of Aβ through its N‐terminal domain, but the more hydrophobic cholesterol and SM molecules would favor binding through its hydrophobic domains. The local concentration of these three lipids into clusters, therefore, represents an “ideal storm” for binding, concentrating, and orienting Aβ on membranes.

Many additional potential nucleators of Aβ aggregation have been suggested, not always with well formulated mechanisms. ApoE,181, 182, 183 collagens and collagen‐related proteins,184, 185, 186, 187, 188 and extracellular matrix glycans,189, 190, 191, 192, 193, 194 among other molecules have all been suggested as sites at which Aβ aggregation might begin. Such suggestions in no way diminish the importance of metal ions or membrane lipids but add to the potential complexity of the process.

A striking feature of Figure 3 is that all three structures of Aβ peptides with bound metal are of Aβ1‐16—not of Aβ40 or Aβ42—for the simple reason that the PDB has no solution structures of metal‐bound Aβ40 or Aβ42 in it. Clearly, this is the case because Aβ1‐16 lacks the hydrophobic regions of Aβ40 and Aβ42, the regions that are necessary to form β‐sheet‐rich fibrils. Thus, Aβ1‐16, whether bound to metal ions or not, does not form fibrils. One might question whether metal ions are truly an example of a surface leading to heterogeneous nucleation. Beyond this semantic point, however, they are certainly catalysts that act through the effects listed earlier: concentration, proximity, orientation, and propinquity of the reactants. As indicated schematically in Figure 4, they can cooperate with other heterogeneous nucleators because when the N‐termini of Aβ molecules are brought together, the C‐termini are perforce brought together as well. The C‐termini can thus bind cooperatively to one another. Factors such as metal ions or lipid surfaces do not exist in biological isolation from one another. Thus, Aβ molecules brought together by metal ions could bind—and bind cooperatively—to an amphiphilic lipid surface, which, too, would favor further aggregation. Aβ molecules associated with a lipid surface could cooperatively bind bridging metal ions—another cooperative effect. The rule of thumb, in other words, appears to be that a little aggregation begets a lot of it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following sources of funding: NIH R01AG048793, Alzheimer's Association Zenith Fellowship Award, NIH MCB TG T32 GM007183.

Srivastava AK, Pittman JM, Zerweck J, et al. β‐Amyloid aggregation and heterogeneous nucleation. Protein Science. 2019;28:1567–1581. 10.1002/pro.3674

Funding information Alzheimer's Association, Grant/Award Number: Zenith Fellowship; National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Number: R01AG048793; National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Number: MCB TG T32 GM007183

REFERENCES

- 1. Hellstrand E, Nowacka A, Topgaard D, Linse S, Sparr E. Membrane lipid co‐aggregation with alpha‐synuclein fibrils. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Iyer A, Petersen NO, Claessens MM, Subramaniam V. Amyloids of alpha‐synuclein affect the structure and dynamics of supported lipid bilayers. Biophys J. 2014;106:2585–2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Last NB, Rhoades E, Miranker AD. Islet amyloid polypeptide demonstrates a persistent capacity to disrupt membrane integrity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9460–9465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schlamadinger DE, Miranker AD. Fiber‐dependent and ‐independent toxicity of islet amyloid polypeptide. Biophys J. 2014;107:2559–2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bender ML, Kezdy J. Mechanism of action of proteolytic enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1965;34:49–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Neet KE. Enzyme catalytic power minireview series. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25527–25528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lomakin A, Chung DS, Benedek GB, Kirschner DA, Teplow DB. On the nucleation and growth of amyloid beta‐protein fibrils: Detection of nuclei and quantitation of rate constants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1125–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murphy RM. Peptide aggregation in neurodegenerative disease. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2002;4:155–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Naiki H, Gejyo F. Kinetic analysis of amyloid fibril formation. Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:305–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tornquist M, Michaels TCT, Sanagavarapu K, et al. Secondary nucleation in amyloid formation. Chem Commun. 2018;54:8667–8684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maruyama M, Arai H, Sugita M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta(1‐42) levels in the mild cognitive impairment stage of Alzheimer's disease. Exp Neurol. 2001;172:433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tapiola T, Alafuzoff I, Herukka SK, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid {beta}‐amyloid 42 and tau proteins as biomarkers of Alzheimer‐type pathologic changes in the brain. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nitsch RM, Rebeck GW, Deng M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid beta‐protein in Alzheimer's disease: Inverse correlation with severity of dementia and effect of apolipoprotein E genotype. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mehta PD, Pirttila T, Mehta SP, Sersen EA, Aisen PS, Wisniewski HM. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid beta proteins 1‐40 and 1‐42 in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oe T, Ackermann BL, Inoue K, et al. Quantitative analysis of amyloid beta peptides in cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer's disease patients by immunoaffinity purification and stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography/negative electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2006;20:3723–3735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson VE, Stewart W, Arena JD, Smith DH. Traumatic brain injury as a trigger of neurodegeneration. Adv Neurobiol. 2017;15:383–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee BG, Leavitt MJ, Bernick CB, Leger GC, Rabinovici G, Banks SJ. A systematic review of positron emission tomography of tau, amyloid beta, and neuroinflammation in chronic traumatic encephalopathy: The evidence to date. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35:2015–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Edwards G 3rd, Moreno‐Gonzalez I, Soto C. Amyloid‐beta and tau pathology following repetitive mild traumatic brain injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;483:1137–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Levy E, Carman MD, Fernandezmadrid IJ, et al. Mutation of the Alzheimers‐disease amyloid gene in gereditary cerebral‐hemorrhage, Dutch type. Science. 1990;248:1124–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nilsberth C, Westlind‐Danielsson A, Eckman CB, et al. The 'Arctic' APP mutation (E693G) causes Alzheimer's disease by enhanced A beta protofibril formation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:887–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grabowski TJ, Cho HS, Vonsattel JP, Rebeck GW, Greenberg SM. Novel amyloid precursor protein mutation in an Iowa family with dementia and severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vinters HV, Wang ZZ, Secor DL. Brain parenchymal and microvascular amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol. 1996;6:179–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morriss‐Andrews A, Shea JE. Kinetic pathways to peptide aggregation on surfaces: the effects of beta‐sheet propensity and surface attraction. J Chem Phys. 2012;136:065103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goldsbury C, Kistler J, Aebi U, Arvinte T, Cooper GJ. Watching amyloid fibrils grow by time‐lapse atomic force microscopy. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoyer W, Cherny D, Subramaniam V, Jovin TM. Rapid self‐assembly of alpha‐synuclein observed by in situ atomic force microscopy. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:127–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seubert P, Vigo‐Pelfrey C, Esch F, et al. Isolation and quantification of soluble Alzheimer's beta‐peptide from biological fluids. Nature. 1992;359:325–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Qiang W, Kelley K, Tycko R. Polymorph‐specific kinetics and thermodynamics of beta‐amyloid fibril growth. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:6860–6871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tycko R. Physical and structural basis for polymorphism in amyloid fibrils. Protein Sci. 2014;23:1528–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tycko R. Amyloid polymorphism: structural basis and neurobiological relevance. Neuron. 2015;86:632–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Petkova AT, Leapman RD, Guo ZH, Yau WM, Mattson MP, Tycko R. Self‐propagating, molecular‐level polymorphism in Alzheimer's beta‐amyloid fibrils. Science. 2005;307:262–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fandrich M, Nystrom S, Nilsson KPR, Bockmann A, LeVine H 3rd, Hammarstrom P. Amyloid fibril polymorphism: a challenge for molecular imaging and therapy. J Intern Med. 2018;283:218–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kumar H, Singh J, Kumari P, Udgaonkar JB. Modulation of the extent of structural heterogeneity in alpha‐synuclein fibrils by the small molecule thioflavin T. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:16891–16903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease: Genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:741–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Czirr E, Cottrell BA, Leuchtenberger S, et al. Independent generation of Abeta42 and Abeta38 peptide species by gamma‐secretase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17049–17054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matsubara T, Nishihara M, Yasumori H, Nakai M, Yanagisawa K, Sato T. Size and shape of amyloid fibrils induced by ganglioside nanoclusters: Role of sialyl oligosaccharide in fibril formation. Langmuir. 2017;33:13874–13881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barrett PJ, Song YL, Van Horn WD, et al. The amyloid precursor protein has a flexible transmembrane domain and binds cholesterol. Science. 2012;336:1168–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marenchino M, Williamson PTF, Murri S, et al. Dynamics and cleavability at the alpha‐cleavage site of APP(684‐726) in different lipid environments. Biophys J. 2008;95:1460–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Beel AJ, Mobley CK, Kim HJ, et al. Structural studies of the transmembrane C‐terminal domain of the amyloid precursor protein (APP): Does APP function as a cholesterol sensor? Biochemistry. 2008;47:9428–9446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Curtain CC, Ali F, Volitakis I, et al. Alzheimer's disease amyloid‐beta binds copper and zinc to generate an allosterically ordered membrane‐penetrating structure containing superoxide dismutase‐like subunits. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20466–20473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bokvist M, Lindstrom F, Watts A, Grobner G. Two types of Alzheimer's beta‐amyloid (1‐40) peptide membrane interactions: Aggregation preventing transmembrane anchoring versus accelerated surface fibril formation. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:1039–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gremer L, Scholzel D, Schenk C, et al. Fibril structure of amyloid‐beta(1‐42) by cryo‐electron microscopy. Science. 2017;358:116–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lopez del Amo JM, Schmidt M, Fink U, Dasari M, Fandrich M, Reif B. An asymmetric dimer as the basic subunit in Alzheimer's disease amyloid beta fibrils. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:6136–6139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Paravastu AK, Leapman RD, Yau WM, Tycko R. Molecular structural basis for polymorphism in Alzheimer's beta‐amyloid fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18349–18354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Qahwash IM, Boire A, Lanning J, Krausz T, Pytel P, Meredith SC. Site‐specific effects of peptide lipidation on beta‐amyloid aggregation and cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36987–36997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Morita S, Mine D, Ishida Y. Effect of saturation in phospholipid/fatty acid monolayers on interaction with amyloid beta peptide. J Biosci Bioeng. 2018;125:457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Caruso B, Ambroggio EE, Wilke N, Fidelio GD. The rheological properties of beta amyloid Langmuir monolayers: Comparative studies with melittin peptide. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2016;146:180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ragaliauskas T, Mickevicius M, Budvytyte R, Niaura G, Carbonnier B, Valincius G. Adsorption of beta‐amyloid oligomers on octadecanethiol monolayers. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;425:159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rocha S, Loureiro JA, Brezesinski G, Pereira Mdo C. Peptide‐surfactant interactions: Consequences for the amyloid‐beta structure. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;420:136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ji SR, Wu Y, Sui SF. Study of beta‐amyloid peptide (Abeta40) insertion into phospholipid membranes using monolayer technique. Biochemistry. 2002;67:1283–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Morel B, Carrasco MP, Jurado S, Marco C, Conejero‐Lara F. Dynamic micellar oligomers of amyloid beta peptides play a crucial role in their aggregation mechanisms. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2018;20:20597–20614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sabate R, Estelrich J. Evidence of the existence of micelles in the fibrillogenesis of beta‐amyloid peptide. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:11027–11032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Soreghan B, Kosmoski J, Glabe C. Surfactant properties of Alzheimers A‐beta peptides and the mechanism of amyloid aggregation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28551–28554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yong W, Lomakin A, Kirkitadze MD, Teplow DB, Chen SH, Benedek GB. Structure determination of micelle‐like intermediates in amyloid beta‐protein fibril assembly by using small angle neutron scattering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:150–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Novo M, Freire S, Al‐Soufi W. Critical aggregation concentration for the formation of early amyloid‐beta (1‐42) oligomers. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Williams TL, Serpell LC. Membrane and surface interactions of Alzheimer's A beta peptide—Insights into the mechanism of cytotoxicity. FEBS J. 2011;278:3905–3917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shen L, Adachi T, Bout DV, Zhu XY. A mobile precursor determines amyloid‐beta peptide fibril formation at interfaces. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:14172–14178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lindberg DJ, Wesen E, Bjorkeroth J, Rocha S, Esbjorner EK. Lipid membranes catalyse the fibril formation of the amyloid‐beta (1‐42) peptide through lipid‐fibril interactions that reinforce secondary pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2017;1859:1921–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Coles M, Bicknell W, Watson AA, Fairlie DP, Craik DJ. Solution structure of amyloid beta‐peptide(1‐40) in a water‐micelle environment. Is the membrane‐spanning domain where we think it is? Biochemistry. 1998;37:11064–11077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Shao H, Jao S, Ma K, Zagorski MG. Solution structures of micelle‐bound amyloid beta‐(1‐40) and beta‐(1‐42) peptides of Alzheimer's disease. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:755–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yamamoto N, Hasegawa K, Matsuzaki K, Naiki H, Yanagisawa K. Environment‐ and mutation‐dependent aggregation behavior of Alzheimer amyloid beta‐protein. J Neurochem. 2004;90:62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rangachari V, Reed DK, Moore BD, Rosenberry TL. Secondary structure and interfacial aggregation of amyloid‐beta(1‐40) on sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8639–8648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bisaglia M, Trolio A, Bellanda M, Bergantino E, Bubacco L, Mammi S. Structure and topology of the non‐amyloid‐beta component fragment of human alpha‐synuclein bound to micelles: Implications for the aggregation process. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1408–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hagihara Y, Hong DP, Hoshino M, Enjyoji K, Kato H, Goto Y. Aggregation of beta(2)‐glycoprotein I induced by sodium lauryl sulfate and lysophospholipids. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1020–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nichols MR, Moss MA, Reed DK, Cratic‐McDaniel S, Hoh JH, Rosenberry TL. Amyloid‐beta protofibrils differ from amyloid‐beta aggregates induced in dilute hexafluoroisopropanol in stability and morphology. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2471–2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nichols MR, Moss MA, Reed DK, Hoh JH, Rosenberry TL. Rapid assembly of amyloid‐beta peptide at a liquid/liquid interface produces unstable beta‐sheet fibers. Biochemistry. 2005;44:165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Serra‐Batiste M, Ninot‐Pedrosa M, Bayoumi M, Gairi M, Maglia G, Carulla N. A beta 42 assembles into specific beta‐barrel pore‐forming oligomers in membrane‐mimicking environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:10866–10871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Korshavn KJ, Satriano C, Lin Y, et al. Reduced lipid bilayer thickness regulates the aggregation and cytotoxicity of amyloid‐beta. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:4638–4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Utsumi M, Yamaguchi Y, Sasakawa H, Yamamoto N, Yanagisawa K, Kato K. Up‐and‐down topological mode of amyloid beta‐peptide lying on hydrophilic/hydrophobic interface of ganglioside clusters. Glycoconj J. 2009;26:999–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yagi‐Utsumi M, Matsuo K, Yanagisawa K, Gekko K, Kato K. Spectroscopic characterization of intermolecular interaction of amyloid beta promoted on GM1 micelles. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;2011:925073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Terakawa MS, Lin YX, Kinoshita M, et al. Impact of membrane curvature on amyloid aggregation. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembranes. 2018;1860:1741–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Fernandez‐Perez EJ, Sepulveda FJ, Peters C, et al. Effect of cholesterol on membrane fluidity and association of a beta oligomers and subsequent neuronal damage: A double‐edged sword. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yu X, Zheng J. Cholesterol promotes the interaction of Alzheimer beta‐amyloid monomer with lipid bilayer. J Mol Biol. 2012;421:561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kalvodova L, Kahya N, Schwille P, et al. Lipids as modulators of proteolytic activity of BACE—Involvement of cholesterol, glycosphingolipids, and anionic phospholipids in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36815–36823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Pester O, Barrett PJ, Hornburg D, et al. The backbone dynamics of the amyloid precursor protein transmembrane helix provides a rationale for the sequential cleavage mechanism of gamma‐secretase. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:1317–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Molander‐Melin M, Blennow K, Bogdanovic N, Dellheden B, Mansson JE, Fredman P. Structural membrane alterations in Alzheimer brains found to be associated with regional disease development; increased density of gangliosides GM1 and GM2 and loss of cholesterol in detergent‐resistant membrane domains. J Neurochem. 2005;92:171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yip CM, Elton EA, Darabie AA, Morrison MR, McLaurin J. Cholesterol, a modulator of membrane‐associated Abeta‐fibrillogenesis and neurotoxicity. J Mol Biol. 2001;311:723–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Habchi J, Chia S, Galvagnion C, et al. Cholesterol catalyses Abeta 42 aggregation through a heterogeneous nucleation pathway in the presence of lipid membranes. Nat Chem. 2018;10:673–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Di Paolo G, Kim TW. Linking lipids to Alzheimer's disease: Cholesterol and beyond. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:284–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sonnino S, Mauri L, Chigorno V, Prinetti A. Gangliosides as components of lipid membrane domains. Glycobiology. 2007;17:1r–13r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Posse de Chaves E, Sipione S. Sphingolipids and gangliosides of the nervous system in membrane function and dysfunction. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1748–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kolter T. Ganglioside biochemistry. ISRN Biochem. 2012;2012:506160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Simons K, Vaz WL. Model systems, lipid rafts, and cell membranes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2004;33:269–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Pike LJ. Lipid rafts: bringing order to chaos. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:655–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Munro S. Lipid rafts: Elusive or illusive? Cell. 2003;115:377–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sagle LB, Ruvuna LK, Bingham JM, Liu CM, Cremer PS, Van Duyne RP. Single plasmonic nanoparticle tracking studies of solid supported bilayers with ganglioside lipids. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:15832–15839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Yuan CB, Furlong J, Burgos P, Johnston LJ. The size of lipid rafts: An atomic force microscopy study of ganglioside GM1 domains in sphingomyelin/DOPC/cholesterol membranes. Biophys J. 2002;82:2526–2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Cebecauer M, Amaro M, Jurkiewicz P, et al. Membrane lipid nanodomains. Chem Rev. 2018;118:11259–11297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Parton RG. Ultrastructural localization of gangliosides; GM1 is concentrated in caveolae. J Histochem Cytochem. 1994;42:155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Mobius W, Herzog V, Sandhoff K, Schwarzmann G. Intracellular distribution of a biotin‐labeled ganglioside, GM1, by immunoelectron microscopy after endocytosis in fibroblasts. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:1005–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Hoshino T, Mahmood MI, Mori K, Matsuzaki K. Binding and aggregation mechanism of amyloid beta‐peptides onto the GM1 ganglioside‐containing lipid membrane. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:8085–8094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yagi‐Utsumi M, Kameda T, Yamaguchi Y, Kato K. NMR characterization of the interactions between lyso‐GM1 aqueous micelles and amyloid beta. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:831–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Yagi‐Utsumi M, Kato K. Structural and dynamic views of GM1 ganglioside. Glycoconj J. 2015;32:105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Brocca P, Berthault P, Sonnino S. Conformation of the oligosaccharide chain of G(M1) ganglioside in a carbohydrate‐enriched surface. Biophys J. 1998;74:309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Sato S, Yoshimasa Y, Fujita D, et al. A self‐assembled spherical complex displaying a gangliosidic glycan cluster capable of interacting with amyloidogenic proteins. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:8435–8439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Matsuzaki K, Kato K, Yanagisawa K. Abeta polymerization through interaction with membrane gangliosides. Biochim Biophs Acta. 2010;1801:868–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Hayashi H, Kimura N, Yamaguchi H, et al. A seed for Alzheimer amyloid in the brain. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4894–4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Yanagisawa K. GM1 ganglioside and Alzheimer's disease. Glycoconj J. 2015;32:87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Matsuzaki K. How do membranes initiate Alzheimer's disease? Formation of toxic arnyloid fibrils by the amyloid beta‐protein on ganglioside clusters. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:2397–2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Kakio A, Nishimoto S, Yanagisawa K, Kozutsumi Y, Matsuzaki K. Interactions of amyloid beta‐protein with various gangliosides in raft‐like membranes: Importance of GM1 ganglioside‐bound form as an endogenous seed for Alzheimer amyloid. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7385–7390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Kim SI, Yi JS, Ko YG. Amyloid beta oligomerization is induced by brain lipid rafts. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:878–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ogawa M, Tsukuda M, Yamaguchi T, et al. Ganglioside‐mediated aggregation of amyloid beta‐proteins (Abeta): Comparison between Abeta‐(1‐42) and Abeta‐(1‐40). J Neurochem. 2011;116:851–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Kakio A, Nishimoto S, Yanagisawa K, Kozutsumi Y, Matsuzaki K. Cholesterol‐dependent formation of GM1 ganglioside‐bound amyloid beta‐protein, an endogenous seed for Alzheimer amyloid. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24985–24990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Mori K, Mahmood MI, Neya S, Matsuzaki K, Hoshino T. Formation of GM1 ganglioside clusters on the lipid membrane containing sphingomyeline and cholesterol. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:5111–5121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Ikeda K, Yamaguchi T, Fukunaga S, Hoshino M, Matsuzaki K. Mechanism of amyloid beta‐protein aggregation mediated by GM1 ganglioside clusters. Biochemistry. 2011;50:6433–6440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Matsubara T, Yasumori H, Ito K, Shimoaka T, Hasegawa T, Sato T. Amyloid‐fibrils assembled on ganglioside‐enriched membranes contain both parallel‐sheets and turns. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:14146–14154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Matsuzaki K, Horikiri C. Interactions of amyloid beta‐peptide (1‐40) with ganglioside‐containing membranes. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4137–4142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Hu Z, Wang X, Wang W, Zhang Z, Gao H, Mao Y. Raman spectroscopy for detecting supported planar lipid bilayers composed of ganglioside‐GM1/sphingomyelin/cholesterol in the presence of amyloid‐beta. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2015;17:22711–22720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Amaro M, Sachl R, Aydogan G, Mikhalyov II, Vacha R, Hof M. GM1 ganglioside inhibits beta‐amyloid oligomerization induced by sphingomyelin. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:9411–9415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Benzinger TLS, Gregory DM, Burkoth TS, et al. Propagating structure of Alzheimer's beta‐amyloid(10‐35) is parallel beta‐sheet with residues in exact register. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13407–13412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Demarco ML, Woods RJ, Prestegard JH, Tian F. Presentation of membrane‐anchored glycosphingolipids determined from molecular dynamics simulations and NMR paramagnetic relaxation rate enhancement. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1334–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Merritt EA, Kuhn P, Sarfaty S, Erbe JL, Holmes RK, Hol WG. The 1.25 A resolution refinement of the cholera toxin B‐pentamer: Evidence of peptide backbone strain at the receptor‐binding site. J Mol Biol. 1998;282:1043–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Neu U, Woellner K, Gauglitz G, Stehle T. Structural basis of GM1 ganglioside recognition by simian virus 40. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5219–5224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Faller P, Hureau C, Berthoumieu O. Role of metal ions in the self‐assembly of the Alzheimer's amyloid‐beta peptide. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:12193–12206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Lovell MA, Robertson JD, Teesdale WJ, Campbell JL, Markesbery WR. Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer's disease senile plaques. J Neurol Sci. 1998;158:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Bush AI. The metallobiology of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Yumoto S, Kakimi S, Ohsaki A, Ishikawa A. Demonstration of aluminum in amyloid fibers in the cores of senile plaques in the brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Inorg Biochem. 2009;103:1579–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Exley C, House E , Polwart A, Esiri MM. Brain burdens of aluminum, iron, and copper and their relationships with amyloid‐beta pathology in 60 human brains. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;31:725–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Lidsky TI. Is the aluminum hypothesis dead? J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56:S73–S79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Rodella LF, Ricci F, Borsani E, et al. Aluminium exposure induces Alzheimer's disease‐like histopathological alterations in mouse brain. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Walton JR. An aluminum‐based rat model for Alzheimer's disease exhibits oxidative damage, inhibition of PP2A activity, hyperphosphorylated tau, and granulovacuolar degeneration. J Inorg Biochem. 2007;101:1275–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Opazo C, Huang X, Cherny RA, et al. Metalloenzyme‐like activity of Alzheimer's disease beta‐amyloid. Cu‐dependent catalytic conversion of dopamine, cholesterol, and biological reducing agents to neurotoxic H(2)O(2). J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40302–40308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Orr ME, Garbarino VR, Salinas A, Buffenstein R. Sustained high levels of neuroprotective, high molecular weight, phosphorylated tau in the longest‐lived rodent. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:1496–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Bush AI, Pettingell WH, Multhaup G, et al. Rapid induction of Alzheimer Abeta amyloid formation by zinc. Science. 1994;265:1464–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Cherny RA, Atwood CS, Xilinas ME, et al. Treatment with a copper‐zinc chelator markedly and rapidly inhibits beta‐amyloid accumulation in Alzheimer's disease transgenic mice. Neuron. 2001;30:665–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Kozin SA, Mezentsev YV, Kulikova AA, et al. Zinc‐induced dimerization of the amyloid‐beta metal‐binding domain 1‐16 is mediated by residues 11‐14. Mol Biosyst. 2011;7:1053–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Talmard C, Guilloreau L, Coppel Y, Mazarguil H, Faller P. Amyloid‐beta peptide forms monomeric complexes with Cu(II) and Zn(II) prior to aggregation. Chembiochem. 2007;8:163–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Liu ST, Howlett G, Barrow CJ. Histidine‐13 is a crucial residue in the zinc ion‐induced aggregation of the Abeta peptide of Alzheimer's disease. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9373–9378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Faller P, Hureau C, La Penna G. Metal ions and intrinsically disordered proteins and peptides: From Cu/Zn amyloid‐beta to general principles. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:2252–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Drochioiu G, Manea M, Dragusanu M, et al. Interaction of beta‐amyloid(1‐40) peptide with pairs of metal ions: An electrospray ion trap mass spectrometric model study. Biophys Chem. 2009;144:9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Bush AI, Pettingell WH Jr, Paradis MD, Tanzi RE. Modulation of Abeta adhesiveness and secretase site cleavage by zinc. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12152–12158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Atwood CS, Moir RD, Huang X, et al. Dramatic aggregation of Alzheimer abeta by Cu(II) is induced by conditions representing physiological acidosis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12817–12826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Atwood CS, Scarpa RC, Huang X, et al. Characterization of copper interactions with Alzheimer amyloid beta peptides: identification of an attomolar‐affinity copper binding site on amyloid beta1‐42. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1219–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Dong J, Atwood CS, Anderson VE, et al. Metal binding and oxidation of amyloid‐beta within isolated senile plaque cores: Raman microscopic evidence. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2768–2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Friedlich AL, Lee JY, van Groen T, et al. Neuronal zinc exchange with the blood vessel wall promotes cerebral amyloid angiopathy in an animal model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3453–3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Miller LM, Wang Q, Telivala TP, Smith RJ, Lanzirotti A, Miklossy J. Synchrotron‐based infrared and X‐ray imaging shows focalized accumulation of Cu and Zn co‐localized with beta‐amyloid deposits in Alzheimer's disease. J Struct Biol. 2006;155:30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Stoltenberg M, Bush AI, Bach G, et al. Amyloid plaques arise from zinc‐enriched cortical layers in APP/PS1 transgenic mice and are paradoxically enlarged with dietary zinc deficiency. Neuroscience. 2007;150:357–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Ha C, Ryu J, Park CB. Metal ions differentially influence the aggregation and deposition of Alzheimer's beta‐amyloid on a solid template. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6118–6125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Ryu J, Girigoswami K, Ha C, Ku SH, Park CB. Influence of multiple metal ions on beta‐amyloid aggregation and dissociation on a solid surface. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5328–5335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Rezaei‐Ghaleh N, Giller K, Becker S, Zweckstetter M. Effect of zinc binding on beta‐amyloid structure and dynamics: implications for Abeta aggregation. Biophys J. 2011;101:1202–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Huang X, Atwood CS, Moir RD, Hartshorn MA, Tanzi RE, Bush AI. Trace metal contamination initiates the apparent auto‐aggregation, amyloidosis, and oligomerization of Alzheimer's Abeta peptides. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:954–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Klug GM, Losic D, Subasinghe SS, Aguilar MI, Martin LL, Small DH. Beta‐amyloid protein oligomers induced by metal ions and acid pH are distinct from those generated by slow spontaneous ageing at neutral pH. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:4282–4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Lim KH, Kim YK, Chang YT. Investigations of the molecular mechanism of metal‐induced Abeta (1‐40) amyloidogenesis. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13523–13532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Solomonov I, Korkotian E, Born B, et al. Zn2+‐Abeta40 complexes form metastable quasi‐spherical oligomers that are cytotoxic to cultured hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:20555–20564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Kulikova AA, Tsvetkov PO, Indeykina MI, et al. Phosphorylation of Ser8 promotes zinc‐induced dimerization of the amyloid‐beta metal‐binding domain. Mol Biosyst. 2014;10:2590–2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Tsvetkov PO, Popov IA, Nikolaev EN, Archakov AI, Makarov AA, Kozin SA. Isomerization of the Asp7 residue results in zinc‐induced oligomerization of Alzheimer's disease amyloid beta(1‐16) peptide. Chembiochem. 2008;9:1564–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Mekmouche Y, Coppel Y, Hochgrafe K, et al. Characterization of the ZnII binding to the peptide amyloid‐beta1‐16 linked to Alzheimer's disease. Chembiochem. 2005;6:1663–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Istrate AN, Kozin SA, Zhokhov SS, et al. Interplay of histidine residues of the Alzheimer's disease Abeta peptide governs its Zn‐induced oligomerization. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Danielsson J, Pierattelli R, Banci L, Graslund A. High‐resolution NMR studies of the zinc‐binding site of the Alzheimer's amyloid beta‐peptide. FEBS J. 2007;274:46–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Bousejra‐ElGarah F, Bijani C, Coppel Y, Faller P, Hureau C. Iron(II) binding to amyloid‐beta, the Alzheimer's peptide. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:9024–9030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Hou L, Zagorski MG. NMR reveals anomalous copper(II) binding to the amyloid Abeta peptide of Alzheimer's disease. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9260–9261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Abelein A, Graslund A, Danielsson J. Zinc as chaperone‐mimicking agent for retardation of amyloid beta peptide fibril formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:5407–5412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Tougu V, Tiiman A, Palumaa P. Interactions of Zn(II) and Cu(II) ions with Alzheimer's amyloid‐beta peptide. Metal ion binding, contribution to fibrillization and toxicity. Metallomics. 2011;3:250–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Branch T, Barahona M, Dodson CA, Ying L. Kinetic analysis reveals the identity of Abeta‐metal complex responsible for the initial aggregation of Abeta in the synapse. ACS Chem Nerosci. 2017;8:1970–1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Syme CD, Nadal RC, Rigby SEJ, Viles JH. Copper binding to the amyloid‐beta (Abeta) peptide associated with Alzheimer's disease—Folding, coordination geometry, pH dependence, stoichiometry, and affinity of Abeta‐(1‐28): Insights from a range of complementary spectroscopic techniques. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18169–18177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Janssen JC, Beck JA, Campbell TA, et al. Early onset familial Alzheimer's disease: Mutation frequency in 31 families. Neurology. 2003;60:235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Zirah S, Kozin SA, Mazur AK, et al. Structural changes of region 1‐16 of the Alzheimer disease amyloid beta‐peptide upon zinc binding and in vitro aging. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2151–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Wetzel R. Kinetics and thermodynamics of amyloid fibril assembly. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Xue WF, Homans SW, Radford SE. Systematic analysis of nucleation‐dependent polymerization reveals new insights into the mechanism of amyloid self‐assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8926–8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Morris AM, Watzky MA, Finke RG. Protein aggregation kinetics, mechanism, and curve‐fitting: A review of the literature. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1794:375–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Huy PD, Vuong QV, La Penna G, Faller P, Li MS. Impact of Cu(II) binding on structures and dynamics of Abeta42 monomer and dimer: Molecular dynamics study. ACS Chem Nerosci. 2016;7:1348–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Jun S, Gillespie JR, Shin BK, Saxena S. The second Cu(II)‐binding site in a proton‐rich environment interferes with the aggregation of amyloid‐beta(1‐40) into amyloid fibrils. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10724–10732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Lee MC, Yu WC, Shih YH, et al. Zinc ion rapidly induces toxic, off‐pathway amyloid‐beta oligomers distinct from amyloid‐beta derived diffusible ligands in Alzheimer's disease. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Mannini B, Habchi J, Chia S, et al. Stabilization and characterization of cytotoxic Abeta40 oligomers isolated from an aggregation reaction in the presence of zinc ions. ACS Chem Nerosci. 2018;9:2959–2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Garai K, Posey AE, Li X, Buxbaum JN, Pappu RV. Inhibition of amyloid beta fibril formation by monomeric human transthyretin. Protein Sci. 2018;27:1252–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Tougu V, Karafin A, Zovo K, et al. Zn(II)‐ and Cu(II)‐induced non‐fibrillar aggregates of amyloid‐beta (1‐42) peptide are transformed to amyloid fibrils, both spontaneously and under the influence of metal chelators. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1784–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]