Abstract

Objectives:

Describe the development and feasibility of a telephone peer support program that provides education, emotional support, and enhances coping skills among rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients.

Methods:

In an academic arthritis center, peer coaches received 5 training modules: 1) definition and expectations of peer coaching, 2) structure/management of phone calls, 3) confidentiality, 4) psychological techniques for encounters, 5) referral guidelines and resources. Follow-up, acceptability and comparison with patients receiving standard care included mean adjusted change differences at 6 months in fatigue, pain, self-efficacy, functional status (SF-12), flare frequency and medication adherence (ASK-20).

Results:

Eighteen peer coaches were assigned on average, 1.7 (SD, 1.4) patients. They spoke 8.4 (SD, 7.2) times; 21 of 29 patients completed the program. The most common topics requested were how to manage flares, 10(48%), medical aspects of RA, 10(48%) and understanding how to live with RA, 9(43%). After 6 months, non-significant improvements occurred in study outcomes (largest changes SF-12 PCS (mean adjusted change (SE) intervention v. standard care, 4.7(2.6) v. 0.5(2.0)) and how RA impacts one’s life (1.8(6.4) v. −4.9(5.8)). Participants reported many benefits from peer support. They felt less alone, 13(62%), more part of a sharing community, 12(57%) and had a better understanding of RA, 9(43%). They felt calmer, 9(43%), less sad,5(24%) and that they had more support from family and friends, 5(24%).

Conclusions:

An RA telephone peer support program is feasible and acceptable to patients. While the study was underpowered to detect statistical improvements, patients reported benefits suggesting the need for randomized evaluation.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, Peer support, Telecare

INTRODUCTION

Many patients with RA can develop progressive disability, work loss, and premature mortality[1, 2]; their pervasive symptoms can influence mood and role functioning[1, 3]. Research has shown that individuals with chronic illness usually require social support to achieve the best physical and emotional outcomes [4, 5]. Riemsa demonstrated an inverse association between fatigue and lower self efficacy and problematic peer support in RA [6]. The purpose of this study was to assess a telephone peer support program’s feasibility, acceptability and value among RA patients.

METHODS

Program Development and Peer Coach Training

The rationale for the program arose from an RA patient advisory group run at the R.B. Brigham Arthritis Center where members reported that their top concerns were feeling isolated and scared when first diagnosed. Peer coaches were recruited from the advisory group, or were recommended by their rheumatologist. They attended two training sessions with the social worker (NFS) that included 5 training modules: 1) definition and expectations of peer coaching, 2) structure/management of phone calls, 3) confidentiality, 4) psychological techniques for encounters, 5) referral guidelines and support resources (Table 1). A Peer Coaching Manual (Appendix 1) and training materials (Appendix 2) that included: 1) the first call sheet, 2) common questions with suggested answers, 3) the structure of the phone call, 4) visualization exercises, and 5) a role play handout were created.

Table 1:

Topics Addressed In Each Peer Coaching Session

| Session 1 | Beginning your Peer Coaching Partnership |

| Introduction | |

| Role of a peer coach | |

| Group activity- getting to know one another | |

| Group discussions | |

| Being a peer coach-benefits and concerns | |

| What kind of support would you have liked when you were first diagnosed? | |

| Role playing exercises | |

| Visualization and relaxation exercise (Mountain Meditation*) | |

| Session 2 | Talking about Rheumatoid Arthritis and the Peer Coaching process |

| Group discussion | |

| Review of peer coaching tools | |

| Meet the clinic doctors and nurses | |

| Peer coaching procedures | |

| How to structure your phone encounter | |

| Responding to certain situations with your partner | |

| Resources for patients | |

| Closing |

All participants were consented and then filled out a questionnaire, to help ascertain the best match for a coach. For the pilot analysis, peer support patients were matched with RA patients receiving standard care based on age, sex, and disease duration ( ± 5 years). This study had approval from the Brigham & Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board (2006P000795).

Patients and peer coaches were encouraged to speak with each other approximately once a week by phone for six months or as needed. Peer coaches tracked their topics and could call into the social worker at any time for support. There was also a regularly scheduled 60 minute group call set up every few months.

Measures and Analysis

Follow-up, acceptability and comparison with patients receiving standard care included adjusted mean change differences at 6 months in fatigue, pain, self-efficacy[7], function (SF-12, MHI 5 )[8, 9], flare frequency and medication adherence (ASK-20)[10]. Baseline comparisons were made with chi-square or t tests. We ran post program analyses with and without the least squares mean (LS mean) method from the GLM procedure to adjust for baseline variable differences (SAS 9.4). As a development and feasibility study (25 patients/group) this study was not powered as a randomized trial. Rather our goal was to observe broader trends.

RESULTS

The study ran from 1/9/2009 to 7/1/2013 with 21 of 29 peer support patients and 20 of 25 standard care patients completing the program. Patients who did not complete the protocol (n=8) did not differ from those who did (n=21) in baseline variables. The patients spoke on average 8.4 times (SD, 7.2) with their coach during the program. More frequent talkers (talking 10 or more times during the study, n=8) were more likely unemployed (100% v. 62%, p=0.04) compared with the less frequent talkers. Eighteen peer coaches had on average 1.7 (SD,1.4) patients. The most common topics requested were how to manage flares, 10(48%), medical aspects of RA, 10(48%) and understanding how to live with RA, 9(43%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Topics Patients Indicated They Would Like to Discuss With A Peer Coach (N=21)

| N(%) | |

|---|---|

| Dealing with flares | 10 (48) |

| Information on medical aspects | 10 (48) |

| Understanding how to live with rheumatoid arthritis | 9 (43) |

| Relationships with family and friends* | 7 (33) |

| Being newly diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis | 6 (29) |

| Work related issues | 6 (29) |

| Feeling more connected and less alone | 6 (29) |

| Joint replacement | 2 (10) |

| Communication with doctors | 1 (5) |

Patients specifically indicated they wanted to discuss stress on marriage, caring for young children and starting a new family

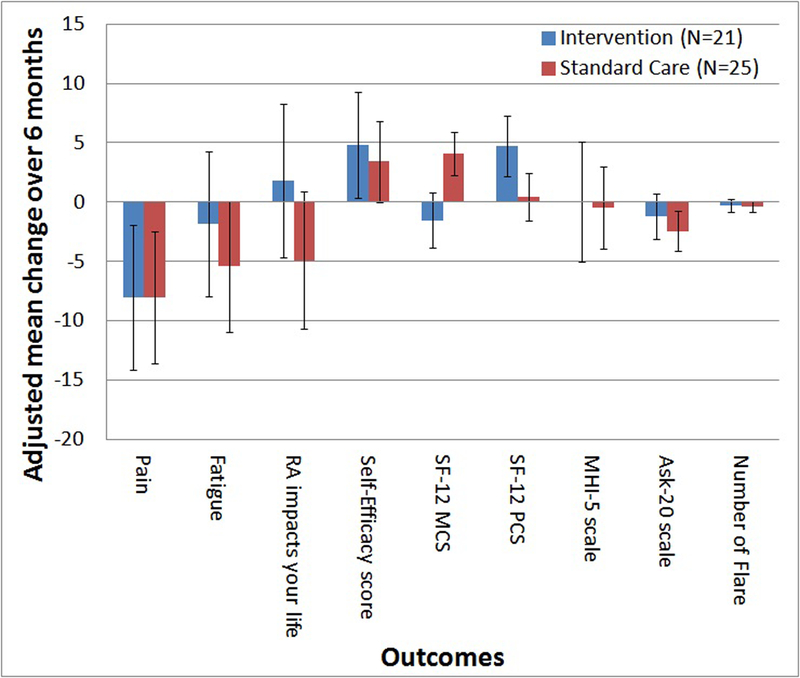

Peer support outcomes and benefits (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adjusted mean change differences and standard error of peer support program v. standard care after 6 months

The peer support and standard care groups had similar demographics but worse baseline outcome variables. Figure 1 indicates the magnitude and directionality of change adjusting for baseline group differences. The largest trends in improvement were the SF-12 PCS (mean adjusted change (SE) intervention v. standard care, 4.7(2.6) v. 0.5(2.0)), and how RA impacts one’s life (1.8(6.4) v. −4.9(5.8)) (p=NS).

Patients in the peer support program reported many benefits (Table 3): 62% noted feeling less alone, 43% had a better understanding of their illness, 57% felt part of an RA community. They also reported feeling calmer (43%), less sad (24%), more support from their family and friends (24%) and that they maintained a healthier lifestyle (24%). Both the peer coaches and the patients remarked on how much the relationship benefited them.

Table 3.

Peer Support Patients’ Perceptions of the Benefits from the Peer Suppor Program (N=21)

| My Peer Coach helped me: | N (%) |

| Feel less alone and more connected | 13 (62) |

| Be a part of a sharing RA community | 12 (57) |

| Have a better understanding of my illness | 9 (43) |

| Feel more in control of my disease and flares | 6 (29) |

| Since beginning the peer coaching program I notice: | N (%) |

| I feel calmer | 9 (43) |

| I am now less likely to feel sad, down or blue | 5 (24) |

| I get more support from family and friends | 5 (24) |

| I am maintaining a healthier lifestyle | 5 (24) |

| I have less pain | 4 (19) |

| I am communicating better with my doctor | 4 (19) |

| It’s easier to manage my medications | 4 (19) |

| I am less likely to forget to take my medications | 4 (19) |

| I feel generally better physically | 3 (14) |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report on the development and feasibility of a telephone peer support program for RA patients. The evaluation indicated that peer support is a feasible and acceptable method of education and support. The patients reported benefits, including a better understanding of their illness, improved coping mechanisms, feeling less isolated and calmer. After 6 months of peer support, the pilot analysis suggested trends towards benefits, however, the study was neither powered nor randomized to assess efficacy.

Research has shown that individuals with chronic illness usually require social support to achieve the best physical and emotional outcomes [4, 5]. Peer support systems matching patients with similar needs have been successful in addiction programs, sleep apnea, oncology treatment, mammography screening, and in promoting other physical and behavioral health outcomes[11–14]. A Cochrane review of 7 trials of peer support telephone health programs showed some evidence of efficacy but none of these trials included arthritis patients[15]. To our knowledge this is the first study to report on the development, feasibility and potential value of a telephone peer support program for RA patients.

There are several limitations to our study. Our study was not a randomized controlled trial, so no conclusions about efficacy could be drawn. Additionally, with 20–25 patients per group there was limited ability to detect anything other than a large (0.8) effect. While study participation was high, enrollment occurred only after rheumatologist referral and training resulting in a relatively slow recruitment. Other suggestions for improvement can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Suggested Modifications for the Peer Support Program

| 1. | Add information about the program to a new RA patient packet |

| 2. | Directly recruit patients from the health care point of contact instead of relying on referrals |

| 3. | Integrate the peer coaches into the clinic structure |

| 4. | Support a dedicated healthcare worker to provide this information to patients |

| 5. | Consider using program in a non-tertiary healthcare setting |

In summary, results from this preliminary study suggest that telephone peer support for RA patients is feasible and acceptable. The patients reported a variety of health and emotional benefits from the program. Peer coaches also found the program enjoyable. Data from the study suggest further development of the program and a randomized, controlled design.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funded by an unrestricted grant from AMGEN

Footnotes

References:

- 1.Strating MM, Van Schuur WH, and Suurmeijer TP, Predictors of functional disability in rheumatoid arthritis: results from a 13-year prospective study. Disabil Rehabil, 2007. 29(10): p. 805–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pincus T, Brooks RH, and Callahan LF, Prediction of long-term mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis according to simple questionnaire and joint count measures. Ann Intern Med, 1994. 120(1): p. 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe F, Hawley DJ, and Wilson K, The prevalence and meaning of fatigue in rheumatic disease. J Rheumatol, 1996. 23(8): p. 1407–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King G, et al. , Social support processes and the adaptation of individuals with chronic disabilities. Qual Health Res, 2006. 16(7): p. 902–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurdle DE, Social support: a critical factor in women’s health and health promotion. Health Soc Work, 2001. 26(2): p. 72–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riemsma RP, et al. , Fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: the role of self-efficacy and problematic social support. Br J Rheumatol, 1998. 37(10): p. 1042–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorig K, et al. , Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum, 1989. 32(1): p. 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware J Jr., Kosinski M, and Keller SD, A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care, 1996. 34(3): p. 220–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berwick DM, et al. , Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Med Care, 1991. 29(2): p. 169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn SR, et al. , Development of the ASK-20 adherence barrier survey. Curr Med Res Opin, 2008. 24(7): p. 2127–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeMolles DA, et al. , A pilot trial of a telecommunications system in sleep apnea management. Med Care, 2004. 42(8): p. 764–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rini C, et al. , Peer mentoring and survivors’ stories for cancer patients: positive effects and some cautionary notes. J Clin Oncol, 2007. 25(1): p. 163–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.West R, Edwards M, and Hajek P, A randomized controlled trial of a “buddy” systems to improve success at giving up smoking in general practice. Addiction, 1998. 93(7): p. 1007–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duan N, et al. , Maintaining mammography adherence through telephone counseling in a church-based trial. Am J Public Health, 2000. 90(9): p. 1468–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dale J, et al. , Peer support telephone calls for improving health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2008(4): p. CD006903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.