Abstract

Background:

The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire is a commonly used patient-reported outcome measure of symptoms and function in people with upper limb conditions. The objectives of this study were to translate and cross-culturally adapt the DASH questionnaire for Tamil population in India and pilot test the questionnaire for feasibility and acceptability.

Materials and Methods:

The translation and cross-cultural adaptation process recommended by the developers of the DASH questionnaire was followed. The prefinal Tamil DASH was tested in people with a wide range of upper limb conditions. Acceptability and feasibility was evaluated by patient feedback and the time taken to complete the questionnaire.

Results:

Around 11 items were adapted to improve the relevance of the questionnaire for Tamil population. Thirty patients were recruited for pilot testing. The prefinal Tamil DASH was found to be relevant and comprehensible to patients (n = 29, Males/Females: 21/8; mean (SD) age: 34 (11.3) years) and feasible to administer. One item “Sexual activities” had more non-respondents (n = 16, 55%). Upon consultation with the developers, an item “Wash and blow dry hair” was further modified and the final Tamil DASH was produced.

Conclusion:

Evaluation of reliability, validity and responsiveness in a large sample would inform the use of Tamil DASH in clinical and research settings.

Keywords: Upper extremity, patient reported outcomes, pain, disability, cross-cultural adaptation

Introduction

Patient-reported outcome measures capture patient perspectives of the effects of healthcare interventions on domains such as function, quality of life, and disability.1 Patient self-reports play a major role in understanding what these constructs mean to people with different clinical conditions. They also compliment objective outcome assessments in the evaluation of healthcare interventions and help inform implications for research and practice to achieve patient-centered care. The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire2,3 is a commonly used patient-reported outcome measure of symptoms and function in people with upper limb musculoskeletal disorders, injuries, surgeries, or nerve conditions. It has 30 items on symptoms/disability covering impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions due to an upper limb condition. Each item is scored on 1–5 Likert scale to rate the level of difficulty, limitations, and the severity of symptoms. A formula is used to calculate the final disability/symptom score that is scaled between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicating greater disability. The DASH cannot be scored if more than three items are missing. The DASH has been translated to around 50 languages so far.

Tamil is one of the oldest languages in the world. In India, it is the first language spoken in the state of Tamil Nadu and by Tamil people migrated to other states such as Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Karnataka. It is also one of the official languages of Singapore and Sri Lanka and spoken by migrant communities in several countries like the United States of America, Canada, France, and the United Kingdom.

The objectives of this study were to translate and cross-culturally adapt the DASH for Tamil speaking population in India, and pilot test the Tamil DASH for feasibility and acceptability.

Materials and Methods

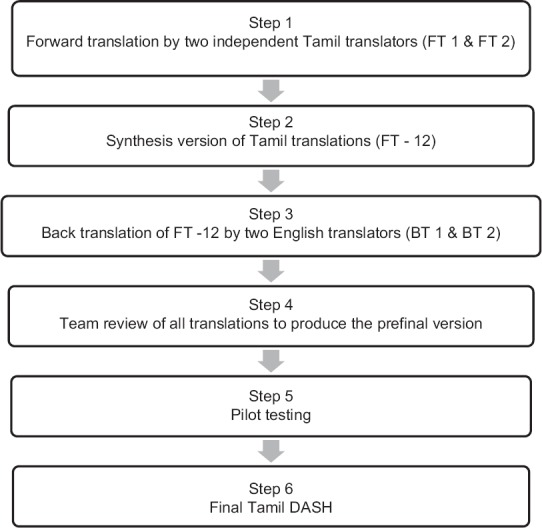

Permission was obtained from the developers of the original DASH questionnaire, Institute for Work and Health (http://www.dash.iwh.on.ca) to translate it into Tamil. The translation and cross-cultural adaptation process recommended by the DASH developers was followed. The guidelines4 involve forward translation (FT), synthesis, back translation (BT), team review, and pilot testing, and appraisal of written reports.

Forward translation-Synthesis version-Back translation

Two physiotherapists with Tamil as their first language translated the DASH questionnaire into Tamil and produced individual written reports on their translations (FT1 and FT2). The translators compared their translations for any ambiguity in the word choices, meaning, or framing of phrases. A synthesis version (FT-12) was created after documenting the translation related queries between FT1 and FT2, and how they were solved.

Two independent translators with a postgraduate degree in English and unaware of the conceptual background of the DASH questionnaire back-translated the FT-12. Both performed individual back translations (BT1 and BT2).

Translation team review

All translations (FT1, FT2, BT1, and BT2), and the synthesis version (FT-12) were reviewed by the team which included translators, a language expert, a process moderator, and a coordinator. Items posing cultural nonequivalence were replaced with items adapting to cultural differences in the prefinal version. The whole review process was documented.

Pilot testing

A cross-sectional study was conducted to test the prefinal Tamil DASH. Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Review Board, Ganga Medical Centre and Hospitals Pvt. Ltd, Coimbatore-641043, Tamil Nadu, India.

Adults with any upper limb disorder for atleast a month and attending the outpatient physiotherapy center in Ganga Medical Centre and Hospitals Pvt Ltd were invited to take part. Ability to read Tamil and willingness to provide signed consent were the other inclusion criteria. We enrolled 30 participants as suggested by the guidelines5 for cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures.

A research physiotherapist screened the volunteers and recruited eligible participants. All participants were informed about the study purpose and signed informed consent was obtained before evaluation. Clear instructions about the use of the DASH questionnaire and how to complete the questionnaire were provided. Participants were also encouraged to respond to questions as completely as possible, and it was emphasized that there are no right or wrong answers. The questionnaire was administered in paper format, and the time taken to complete the questionnaire was recorded. Participants also completed a brief feedback questionnaire developed by the research team.

Results

Translation and cultural adaptation

The translation process of Tamil DASH is presented in Figure 1. In general, both forward translators reported that the translation process was easy and straightforward, except for a few items. For example, direct translation of “pins and needles” in Tamil would not be meaningful to describe the sensations. Similarly, both forward translators found it difficult to differentiate between terms “job,” “work” and “task” in Tamil. Another item was “playing musical instrument or sport.” In Tamil, translating “playing” and using the same for “playing musical instrument” and “playing sport” will not represent both activities at a time. To resolve this, two different action words were chosen to distinctively describe each of them.

Figure 1.

Tamil DASH translation process

On comparing FT1 and FT2, the frequent discrepancies that were noted were translators’ choices of different words for a single term. These were resolved by choosing the most relevant word from FT1 or FT2. In a few cases, the use of less appropriate words was identified and replaced with more appropriate words for the synthesis FT1-2 version. Both back translators had no issues translating the FT1-2.

The team reviewed the translations and agreed on the cultural adaptations for Tamil people living in India [Table 1]. For example, Item 7, “Wash walls” and “Wash floors” were replaced with common culture-specific household tasks of “sweeping floors” and “wiping floors.” Similarly, ‘Lbs’ are not used across India and replaced with “kilograms.” We also specified “5 kg” instead of 4.5 kg which approximates 10 Lbs’. Tamil people are more familiar with 5-kg weight as they commonly use the same denomination in their purchase of staple foods including rice, wheat flour, and grocery. Other examples included yardwork, sweater, knife for cutting food, knitting, blow dry hair, etc. which were replaced with culturally relevant activities.

Table 1.

Cultural-adaptation of DASH items in Tamil

| DASH items that required cultural adjustment | Adaptations in Tamil DASH |

|---|---|

| Item 7: “Wash walls” and “Wash floors” are not common practices in Tamil people | We chose culturally relevant practices such as “sweeping floors and wiping floors” |

| Item 8: Yardwork is not a common practice in Tamil people | We replaced “Yard work” with “cleaning the front of the house” |

| Item 11: Lb is not a common metric used in India. | We used “Kilograms” the commonly used metric across India. We also used an approximate weight of 5 kg |

| Item 12: Tamil people do not commonly use the Tamil word for “Bulb” in their daily life | ’Bulb’ was pronounced same as in English for vocabulary equivalence. |

| Item 13: Tamil people usually air-dry their hair. | We replaced “Blow dry hair” with “air-dry the hair” for experiential equivalence. On consultation with IWH, this item was further modified to represent a functional task “drying wet hair with towel” |

| Item 15: Sweaters are not worn in most regions of Tamil Nadu | We replaced “Sweater” with day-to-day clothing, for example, blouse in women and banian in men |

| Item 16: Translating ’Using a knife to cut food’ in Tamil would not have an appropriate meaning. | We used “cut vegetables” instead of “cutting food” |

| Item 17: Knitting is not a usual activity for Tamil people | We chose “stitching” to replace “knitting” |

| Item 18: Golf is not a common sports activity for Tamil people | We replaced “Golf” with “Cricket” a familiar sport for Tamil people |

| Item 19: Frisbee is not a common sports activity for Tamil people | We replaced “Frisbee” with a simple play activity such as “throwing a ball” |

| Item 26: Translating “pins and needles” directly into Tamil would not give appropriate meaning to describe the sensation. | We added “like” with “pins and needles” to describe the sensations clearly. |

DASH=Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand, IWH=Institute for Work and Health

Tamil people do not use the Tamil word ‘minvilaku’ for “bulb” in their daily life. Hence, we decided not to translate “bulb” but to keep it in English and wrote “bulb” in Tamil. In Item 26, we described “pins and needles” by adding “as like pricked by pins and needles.”

Pilot testing

One participant did not complete more than three DASH items. The demographic characteristics of 29 participants are presented in Table 2. The DASH disability/symptom score (n = 29) ranged from 7.8 to 79.3. The mean score was 44.8 (Standard deviation 19.9). Participants self-reported a moderate level of disability for most items, and increased difficulty with recreational activities that required some force through the arm, shoulder, and hand (Item 18). It took an average of 8.5 minutes (SD 4.4) to complete the questionnaire. Items 8, 17, 22, 23 and 30 were not completed by one participant each and two participants did not respond to item 29. 16/29 (55%) participants did not respond to item 21, “sexual activities.”

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants

| Gender | |

|---|---|

| Males, n | 21 |

| Females, n | 8 |

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) years | 34 (11.3) |

| Range | 18-62 |

| Level of formal education | |

| School education, n | 10 |

| Diploma, n | 2 |

| Graduate, n | 11 |

| Postgraduate, n | 1 |

| Industrial training, n | 2 |

| Missing, n | 3 |

| Clinical conditions | |

| Injury (machine, violence), n | 12 |

| Fracture, n | 3 |

| Posttraumatic stiffness, n | 1 |

| Contracture due to burns, n | 1 |

| Nerve paralysis, n | 1 |

| Surgery (e.g., capsulotomy, tendon repair), n | 8 |

| Finger amputation, n | 1 |

| Missing, n | 2 |

| Duration of symptoms | |

| Mean (SD) months | 9.7 (16.6) |

| Range | 1-60 |

| Side affected | |

| Right, n | 13 |

| Left, n | 12 |

| Both sides, n | 2 |

| Missing, n | 2 |

SD=Standard deviation

Participants’ scores on the feedback questionnaire are presented in Table 3. In general, participants reported that the Tamil DASH was useful and easy to understand, and the questions were relevant to their upper limb condition. The questionnaire was easy to complete and the choice of Tamil words was acceptable.

Table 3.

Feedback on Tamil DASH

| Feedback questionnaire items | 1-5 Likert scales | n Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Ease of comprehension | 1-Very easy 2-Easy 3-Moderate 4-Difficult 5-Very difficult |

n=29 1.9 (0.8) |

| Relevance of DASH items to shoulder, arm, wrist, or hand condition | 1- Excellent 2- Good 3-Moderate 4-Poor 5-Very poor |

n=29 1.9 (0.6) |

| Ease of choosing a response | 1-Very easy 2-Easy 3-Moderate 4-Difficult 5-Very difficult |

n=28 1.9 (0.7) |

| Ease of completing items | 1-Very easy 2-Easy 3-Moderate 4-Difficult 5-Very difficult |

n=28 1.9 (0.8) |

| Choice of Tamil words | 1- Excellent 2- Good 3-Moderate 4-Poor 5-Very poor |

n=29 1.6 (0.7) |

| Perceived usefulness | 1- Excellent 2- Good 3-Moderate 4-Poor 5-Very poor |

n=29 1.8 (0.6) |

DASH=Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand, SD=Standard deviation

Consultation with developers of the DASH questionnaire

The developers reviewed our full report on the translation, cultural adaptation, and pilot testing process. In our prefinal version, Item 13, “Wash or blow-dry your hair,” the Tamil translation implied the task of drying hair in the air. It was recommended to describe the task in a “functional” way instead of passively drying the hair in the air. Hence, we rephrased as “drying wet hair using towel” to represent a functional task that involves sustained shoulder elevation and external rotation movements. After this revision, the Tamil DASH was approved by the Institute for Work and Health.

Discussion

This study describes the process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Tamil DASH. Overall, there were some discrepancies between FTs, which were efficiently resolved. Many cross-cultural adaptations (for example, finding culturally relevant alternatives for less applicable recreational activities, daily tasks, norms, etc.) in Tamil were like other Asian translations.6 Participants found Tamil DASH easy to understand and complete, and also relevant to their upper limb condition.

Yardwork is not a culturally relevant activity for Tamil people as in other Asian populations.7 Other DASH items that required cultural-specific adaptations included putting sweater;8,9 playing Frisbee, and knitting and Lbs measurement as in Thai version;10 playing golf as in Chinese11 and retaining “bulb” in local language as in Hindi version.8 As in other Asian versions of DASH in Arabic7 Hindi,8 Thai,10 Hong Kong Chinese,11 Korean,12 and Persian,13 Item 21 “Sexual activities” had the maximum nonrespondents. We expected more than 75% of nonrespondents, considering the culture of silence and hesitation among Tamil people to comment on sexual activities. However, the proportion of people (13/29, 45%) who responded was comparatively higher than other translations10,11,14 which might be attributed to the number of male respondents (11/13, 85%). Further, there were no issues completing gender-specific tasks of the Tamil population such as making a meal, household work, or making a bed.

The average time taken to complete the questionnaire was similar to the Japanese version.14 This corresponds to the feasibility of using Tamil DASH in time constrained clinical settings.

The approved Tamil DASH is available from the DASH website.15

Conclusion

Using reliable and valid outcome measures is a key requirement in evidence-based practice. The systematic approach of the cross-cultural adaptation process and testing of the Tamil DASH questionnaire has been successful. Further evaluation of psychometric properties of test-retest reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Tamil DASH questionnaire in an adequate study sample would support its use in clinical practice and research.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors declare that participants have been clearly informed of the study procedures and signed consent have been obtained.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs. Anita Kathiravan and Mrs. Blessingta Vijay who worked on the back-translation and Late Mr. Muniappan for his guidance in the translation process. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Ravindra Bharathi and Dr. Raja Sabapathy for providing support with data collection at the study site.

References

- 1.Meadows KA. Patient-reported outcome measures: An overview. Br J Community Nurs. 2011;16:146–51. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2011.16.3.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaton DE, Katz JN, Fossel AH, Wright JG, Tarasuk V, Bombardier C. Measuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand outcome measure in different regions of the upper extremity. J Hand Ther. 2001;14:128–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: The DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. The upper extremity collaborative group (UECG) Am J Ind Med. 1996;29:602–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<602::AID-AJIM4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaton D, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Recommendations for the cross-cultural adaptation of the DASH & QuickDASH outcome measures. Inst Work Health. 2007;1:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3186–91. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alotaibi NM. The cross-cultural adaptation of the disability of arm, shoulder and hand (DASH): A systematic review. Occup Ther Int. 2008;15:178–90. doi: 10.1002/oti.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alotaibi NM, Aljadi SH, Alrowayeh HN. Reliability, validity and responsiveness of the Arabic version of the disability of arm, shoulder and hand (DASH-arabic) Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:2469–78. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1136846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehta SP, Tiruttani R, Kaur MN, MacDermid J, Karim R. Psychometric properties of the Hindi version of the disabilities of arm, shoulder, and hand: A pilot study. Rehabil Res Pract. 2015;2015:482378. doi: 10.1155/2015/482378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perera A, Perera C, Karunanayake A. Cross-cultural adaptation of the disability of arm, shoulder, and hand questionnaire (DASH): English in to Sinhala translation. Physiotherapy. 2015;101:e1195. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tongprasert S, Rapipong J, Buntragulpoontawee M. The cross-cultural adaptation of the DASH questionnaire in Thai (DASH-TH) J Hand Ther. 2014;27:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee EW, Chung MM, Li AP, Lo SK. Construct validity of the Chinese version of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire (DASH-HKPWH) J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JY, Lim JY, Oh JH, Ko YM. Cross-cultural adaptation and clinical evaluation of a Korean version of the disabilities of arm, shoulder, and hand outcome questionnaire (K-DASH) J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:570–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mousavi SJ, Parnianpour M, Abedi M, Askary-Ashtiani A, Karimi A, Khorsandi A, et al. Cultural adaptation and validation of the Persian version of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) outcome measure. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22:749–57. doi: 10.1177/0269215508085821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imaeda T, Toh S, Nakao Y, Nishida J, Hirata H, Ijichi M, et al. Validation of the Japanese society for surgery of the hand version of the disability of the arm, shoulder, and hand questionnaire. J Orthop Sci. 2005;10:353–9. doi: 10.1007/s00776-005-0917-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamil DASH 2018-03-17. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 17]. Available from: http://www.dash.iwh.on.ca/available-translations .