Abstract

Objectives

Many predictive or influencing factors have emerged in investigations of the cognitive reserve model of patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD). For example, neuronal injury, which correlates with cognitive decline in AD, can be assessed by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission-tomography (FDG-PET), structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and total tau in cerebrospinal fluid (CSFt-tau), all according to the A/T/N-classification. The aim of this study was to calculate residual cognitive performance based on neuronal injury biomarkers as a surrogate of cognitive reserve, and to test the predictive value of this index for the individual clinical course.

Methods

110 initially mild cognitive impaired and demented subjects (age 71 ± 8 years) with a final diagnosis of AD dementia were assessed at baseline by clinical mini-mental-state-examination (MMSE), FDG-PET, MRI and CSFt-tau. All neuronal injury markers were tested for an association with clinical MMSE and the resulting residuals were correlated with years of education. We used multiple regression analysis to calculate the expected MMSE score based on neuronal injury biomarkers and covariates. The residuals of the partial correlation for each biomarker and the predicted residualized memory function were correlated with individual cognitive changes measured during clinical follow-up (27 ± 13 months).

Results

FDG-PET correlated highly with clinical MMSE (R = −0.49, p < .01), whereas hippocampal atrophy to MRI (R = −0.15, p = .14) and CSFt-tau (R = −0.12, p = .22) showed only weak correlations. Residuals of all neuronal injury biomarker regressions correlated significantly with education level, indicating them to be surrogates of cognitive reserve. A positive residual was associated with faster cognitive deterioration at follow-up for the residuals of stand-alone FDG-PET (R = −0.36, p = .01) and the combined residualized memory function model (R = −0.35, p = .02).

Conclusions

These findings suggest that subjects with higher cognitive reserve had accumulated more pathology, which subsequently caused a faster cognitive decline over time. Together with previous findings suggesting that higher reserve is associated with slower cognitive decline, we propose a biphasic reserve effect, with an initially protective phase followed by more rapid decompensation once the protection is overwhelmed.

Keywords: Cognitive performance, Neuronal injury biomarkers, Alzheimer's disease, FDG-PET, Cognitive reserve

Highlights

-

•

Neuronal injury biomarkers were investigated for assessment of cognitive reserve.

-

•

FDG-PET correlates better with cognition than CSF-Tau or hippocampal atrophy.

-

•

Residuals of neuronal injury marker correlations are associated with education.

-

•

Regression models can serve to calculate surrogates of individual cognitive reserve.

-

•

Higher cognitive reserve results in faster cognitive decline over time.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD), being the most common form of neurodegenerative dementia, is having an enormous impact on health care systems in societies with aging populations (Ziegler-Graham et al., 2008). In the majority of clinical routine settings, the diagnosis of AD is still based on clinical and behavioural changes and exclusion of other medical causes. Classically, a firm diagnosis of AD required post mortem neuropathological findings of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles and extracellular amyloid plaques (Braak and Braak, 1991) but in recent years, in vivo biomarkers are emerging as sufficient diagnostic criteria for AD (Dubois et al., 2014; McKhann et al., 2011; Jack Jr et al., 2018). This diagnosis derives from the non-invasive detection of the hallmark pathologies of β-amyloid (Aβ) and tau-positivity, plus neurodegeneration/neuronal injury, which are together known as the A/T/N classification scheme (Jack Jr et al., 2016).

In the A/T/N scheme, positron emission tomography (PET) with specific ligands for Aβ or tau and/or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) measurements give readouts for abnormal protein aggregates in living brain. Neurodegeneration/neuronal injury is detected by T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), providing a measure of grey matter atrophy in key regions such as the hippocampus, ventricular dilation, or sulcal widening (Jack et al., 2010). Alternately, measurement of total soluble tau proteins in the CSF serves as an indicator of global neuronal injury (Bartlett et al., 2012). Finally, PET with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) can reveal reduced cortical glucose utilization, which is indicative of the impaired synaptic dysfunction in AD subjects compared to age-matched healthy controls (Mosconi et al., 2008). In general, scores for the several biomarkers of neurodegeneration/neuronal injury all correlate with the severity of AD pathology post mortem (Landau et al., 2010), supporting their use in diagnostics. Nonetheless, results of a recent investigation underlined the limited agreement between binarized read-outs of neuronal injury biomarkers (Alexopoulos et al., 2014).

The contemporary concept of cognitive reserve as a moderating factor between the extent of neurodegeneration and clinical deterioration entails a complex model wherein many different protective environmental factors contribute to cognitive reserve, in particular the number of years of education (YoE) (Yoon et al., 2016), but also occupational complexity (Andel et al., 2006; Potter et al., 2008), extent of intellectual activities during leisure time (Wilson et al., 2002; Verghese et al., 2003), or higher physical fitness (Okonkwo et al., 2014; Tolppanen et al., 2015; Duzel et al., 2016). Different imaging findings suggest that both structural and functional brain differences may underlie cognitive reserve, e.g. a larger premorbid brain volume (Perneczky et al., 2010) or greater left frontal cortex connectivity (Franzmeier et al., 2018).

How exactly to quantify cognitive reserve is another matter. Cognitive reserve is conceptualized as the extent to which cognitive performance exceeds what might be expected from the level of brain pathology. Residualized cognitive performance (after regression of pathology markers) has been previously suggested as an objective marker of reserve predictive for future cognitive changes in aging and AD (Reed et al., 2010). However, it remains uncertain which marker(s) of brain pathology should be used to estimate the expected level of cognitive performance. Here, we propose to use the neurodegeneration biomarkers that were recently introduced for the purely biomarker-based A/T/N staging system of AD (Jack Jr et al., 2016), where “A” stands for PET assessment of amyloidosis, “T” for CSF assessment of total tau pathology (CSFt-tau), and “N” stands for neurodegeneration illustrated by structural MRI.

Thus, we first correlated biomarkers for neuronal injury in a series of patients with their individual cognitive status measured by MMSE and tested for an association of individual residuals with YoE as a predictor of cognitive reserve. We then created a model based on biomarkers of neuronal injury along with relevant covariates for AD to calculate the expected individual cognitive performance. Finally, we tested if the discrepancy between measured and model-derived cognitive performance, as a surrogate of cognitive reserve, could predict cognitive deterioration in later follow-up at the single patient level.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and patient enrollment

The study included patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or mild to moderate AD dementia, all confirmed as having AD dementia in clinical follow-up (27 ± 13 months). The subjects were recruited and scanned in a clinical setting at the University of Munich Department of Nuclear Medicine between 2010 and 2016. Patients had been referred by the Departments of Neurology, Psychiatry and Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research. The local ethics committee approved analysis of the anonymized data (application 399–09). All subjects underwent clinical dementia workup, including detailed cognitive testing, structural MRI, CSF-examination, and FDG-PET. Requirements for inclusion were clinically suspected AD, an available structural MRI, and a CSF-examination. Confirmation of AD during a clinical follow-up of ≥12 months was obligatory for inclusion. Patients with insufficient clinical data (e.g. no clinical follow-up confirming the suspected diagnosis) were excluded. Further exclusion criteria were stroke, major depression, cerebral manifestation of malignancies, and other severe neurological or psychiatric disorders.

2.2. Clinical assessment and cognitive testing

We first conducted a clinical neurological examination and neuropsychological testing consisting of the CERAD plus battery which includes the Mini-Mental-State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975), Trail-Making Test A and B, as well as verbal fluency tests (Morris et al., 1989; Chandler et al., 2005). A summed CERAD score was assembled according to (Chandler et al., 2005). YoE was recorded, and laboratory parameters for metabolic causes of cognitive impairment (vitamin B12, thiamine and folate levels, thyroid and liver function) were assessed.

2.3. MRI

MRI was performed (1.5/3.0 Tesla magnets) using a T1w sequence for atrophy assessment and a T2w-FLAIR sequence for screening of leukoencephalopathy. The hippocampal atrophy as a biomarker for neuronal injury was rated visually by an expert in Radiology, using the Scheltens-Scale for medial temporal lobe atrophy, which ranges from 0 to 4 (for representative T1 MRI images see Fig. 1) (Scheltens et al., 1992). A summed score was assembled for both hemispheres. In addition, white matter lesions visible on T2 MRI images were assessed using the Fazekas-Score (ranging from 0 to 3) by the same expert (Fazekas et al., 1987; Kim et al., 2008).

Fig. 1.

Evaluation scheme for magnetic resonance imaging. Representative T1 structural MR images for a Scheltens-Score 0 (no atrophy), 1 (only widening of choroid fissure), 2 (also widening of temporal horn of lateral ventricle), 3 (moderate loss of hippocampal volume, decrease in height) to 4 (severe volume loss of hippocampus).

2.4. CSF

Lumbar CSF was collected for measurement of phosphorylated tau (previously established threshold for abnormal p-tau: 61 pg/ml) and total tau by radioimmunoassay (previously established threshold: 450 pg/ml) (Meredith Jr et al., 2013).

2.5. FDG-PET imaging

2.5.1. FDG PET acquisition

FDG was purchased commercially. FDG-PET images were acquired using a 3-dimensional GE Discovery 690 PET/CT scanner or a Siemens ECAT EXACT HR+ PET scanner. All patients fasted for at least six hours, and had a plasma glucose level <120 mg/dl (6.7 mM) at time of tracer administration, when a dose of 140 ± 7 MBq [18F]-FDG was injected as a slow intravenous bolus while the subject sat quietly in a room with dimmed light and low noise level. A static emission frame was acquired from 30 min to 45 min p.i. for the GE Discovery 690 PET/CT, or from 30 min to 60 min p.i. for the Siemens ECAT EXACT HR+ PET scanner. A low-dose CT scan (GE) or a transmission scan with external 68Ge-sources (Siemens) was performed prior to the static acquisition for attenuation correction. PET data were reconstructed iteratively (GE) or with filtered back-projection (Siemens).

2.5.2. Visual analysis of FDG PET

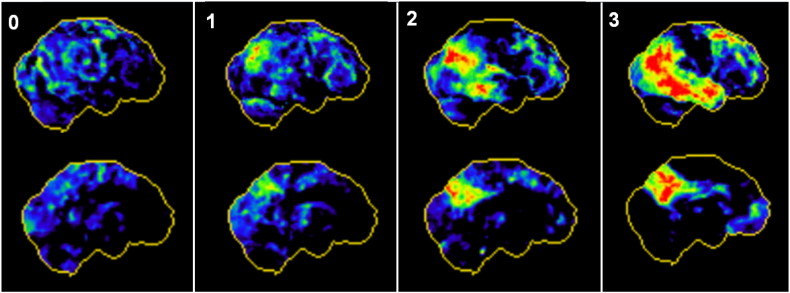

For visual image interpretation of FDG-PET images, three-dimensional stereotactic surface projections (3D-SSP) (Minoshima et al., 1995) were generated using the software Neurostat (Department of Radiology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, U.S.A.). An expert in Nuclear Medicine visually assessed the 3D-SSP images using tracer uptake and Z-score maps (with global mean scaling). Voxel-wise Z-scores were calculated in Neurostat by comparing the individual tracer uptake to historical FDG-PET images from a healthy age-matched cohort (n = 18). The reader had access to clinical information and structural imaging, which was conducted in all cases. To allow a visual based quantification, we applied a simplified approach of the t-sum method published by Herholz and coworkers (Herholz et al., 2002). Preselected AD-typical regions in FDG-PET (bilateral parietal lobe, temporal lobe and posterior cingulate cortex) were rated based on the surface projections into four grades of neuronal injury ranging from 0 (no neuronal injury) to 3 (severe neuronal injury), with representative images shown in Fig. 2. A combined FDG-PET Score (0–18) was calculated by summing the values for all six regions.

Fig. 2.

Evaluation scheme for positron emission tomography. Representative three-dimensional stereotactic surface projections (3D-SSP) of normalized tracer uptake from right lateral (upper row) and left medial (bottom row) for no (0), mild (1), moderate (2) and severe neuronal injury (3) in all six Alzheimer's disease typical regions.

2.5.3. Semiquantitative analysis of FDG PET

Semiquantitative analysis of FDG uptake was performed to validate the visual findings. All individual FDG-PET image volumes were registered to an in-house FDG-PET template within the MNI space (Daerr et al., 2017) using PMOD software (version 3.5, PMOD Technologies Ltd., Zürich, Switzerland). We measured the mean activity within bilateral parietal and temporal volumes of interest (VOIs: posterior cingulate gyrus, superior parietal gyrus, remaining parietal lobe, posterior temporal lobe, middle temporal gyrus) of the Hammers atlas (Hammers et al., 2003), corresponding to the affected regions seen in Fig. 2. Measured regional activities were scaled to standardized uptake value rations relative to a cerebellum reference region.

2.6. Calculations and statistical analysis

Scheltens-Scale scores, CSFt-tau concentrations and FDG-PET read-outs were correlated with clinical MMSE-Scores (MMSEOBSERVED), corrected for age, gender and the severity of white matter lesions (Fazekas-Score) and the residuals (RESPET, RESMRI, RESCSF) were archived. The residuals of all regression analyses were correlated with YoE.

A regression analysis was performed by a model including the three A/T/N biomarkers of neuronal injury, YoE, and covariates (age, gender, leukoencephalopathy) as predictors to anticipate the MMSE score and calculate a MMSE score based on the biomarkers of neuronal injury (MMSEPREDICTED = MMSE neuronal injury). A surrogate score for the individual cognitive reserve was calculated by ΔMMSE = MMSEOBSERVED - MMSEPREDICTED. ΔMMSE was compared to the natural variance of the MMSE methods using standard deviations (SD) of historical test-retest analyses (Tombaugh, 2005).

Clinical deterioration was measured by clinical follow-up assessment of at least 12 months. Each subject's annual rate of decline in MMSE-score was correlated with the residuals using only a single neuronal injury marker (RESPET, RESMRI, RESCSF) or with ΔMMSE, together with age and gender serving as covariates. A significance level of p < .05 was applied in all analyses. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS (version 24.0, IBM, Chicago, IL).

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and neuronal injury biomarkers

The study population consisted of 110 subjects (56.4% female) presenting with cognitive impairment, of whom 32 (29.1%) were initially classified as MCI and 78 (70.9%) as AD. For details of the study population see Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of the study population. Demographics, covariates, baseline cognitive testing and findings of neuronal injury biomarkers of the study population.

| All subjects | MCI | AD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 110 | 32 | 78 |

| Age (y ± SD) | 70.5 ± 7.7 | 71.7 ± 6.4 | 70.0 ± 8.2 |

| Gender (♂male/♀female) | ♂48/♀62 | ♂15/♀17 | ♂33/♀45 |

| Education (y ± SD) | 12.6 ± 3.2 | 14.9 ± 3.9 | 12.0 ± 2.6 |

| Fazekas-score (0–3) | 1.22 ± 0.53 | 1.34 ± 0.48 | 1.17 ± 0.54 |

| Baseline MMSE ± SD | 22.9 ± 4.3 | 25.8 ± 2.2 | 21.7 ± 4.4 |

| CERAD (n = 97) | 55.5 ± 13.0 | 62.1 ± 9.2 | 52.7 ± 13.4 |

| Verbal fluency (Animals) | 12.9 ± 5.2 | 15.3 ± 4.4 | 11.9 ± 5.2 |

| Modified BNT | 12.4 ± 2.6 | 13.1 ± 1.9 | 12.1 ± 2.8 |

| Word list learning | 11.6 ± 4.6 | 13.9 ± 4.2 | 10.6 ± 4.5 |

| Constructional praxis | 9.3 ± 2.1 | 10.2 ± 1.3 | 8.9 ± 2.3 |

| Word list recall | 2.3 ± 1.9 | 2.6 ± 1.9 | 2.1 ± 1.9 |

| Word list recognition-discriminability (%) | 84.6 ± 12.0 | 85.2 ± 10.9 | 84.4 ± 12.4 |

| Verbal fluency (S-Words) | 9.4 ± 5.2 | 11.4 ± 5.2 | 8.6 ± 4.9 |

| TMT-A (sec) | 85.4 ± 41.6 | 72.6 ± 36.0 | 91.5 ± 42.9 |

| TMT-B (sec) | 191.5 ± 73.6 | 180.8 ± 73.8 | 202.8 ± 73.5 |

| Clinical follow-up in months (n = 46; ± SD) | 27.0 ± 12.5 | 25.5 ± 11.6 | 28.2 ± 13.3 |

| Scheltens-score (0–8) | 4.07 ± 1.94 | 3.94 ± 1.91 | 4.13 ± 1.96 |

| CSFtotal-tau (pg/ml) | 545.7 ± 309.0 | 462.9 ± 203.1 | 580.0 ± 338.5 |

| CSFtotal-tau (% positive > 450) | 55% | 47% | 58% |

| CSFp-tau (pg/ml) | 79.1 ± 33.9 | 78.0 ± 31.5 | 79.6 ± 35.0 |

| CSFp-tau (% positive ≥ 61) | 71% | 66% | 73% |

| Visual FDG-PET (0–18) | 7.31 ± 3.66 | 5.00 ± 2.57 | 8.26 ± 3.63 |

3.2. Correlation of neuronal injury biomarkers with cognitive performance

In subjects who had baseline MMSE and CERAD plus battery scores (n = 97), the two test results had a strong positive correlation (r = 0.699; p < .001). We present below the correlations between MMSEOBSERVED scores and neuronal injury marker (the corresponding correlations for CERAD plus battery scores are presented in Supplement Figure 1). Visual and semiquantitative FDG-PET read-outs likewise showed highly congruent results (R = 0.70, p < .01, see Supplement Figure 2), so we elected to use the clinically common visual read-out of surface projections in the regions known to be affected in AD for further analyses.

FDG-PET grading showed the highest association with the MMSEOBSERVED score (β = −0.49, p < .001) than did grading of the hippocampal volume in MRI (β = −0.15, p = .14) and the CSFt-tau levels (β = −0.12, p = .22; see Fig. 3A–C); FDG-PET, age, gender, and leukoencephalopathy accounted for 21% of the variance in MMSEOBSERVED (F(4,106) = 8.2, p < .01, R2 = 0.24, R2Adjusted = 0.21). The hippocampal volume in MRT together with age, gender, and leukoencephalopathy accounted for 1% of the variance in MMSEOBSERVED (F(4,106) = 1.4, p = .24, R2 = 0.05, R2Adjusted = 0.01). The CSFt-tau levels, age, gender, and leukoencephalopathy together accounted for 1% of the variance in MMSEOBSERVED (F(4,106) = 1.2, p = .31, R2 = 0.04, R2Adjusted = 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Association of neuronal injury biomarker findings with cognitive performance and education level. A: Regression analyses of neuronal injury biomarkers with clinical-assessed MMSE scores. B: Correlation of regression residuals (RESPET, RESMRI, RESCSF) with years of education for all neuronal injury biomarkers. Values of the regression analyses are presented as residuals.

The correlation of regression residuals (RESPET, RESMRI, RESCSF) with the YoE revealed significant positive associations for all three biomarkers (MRI: R = 0.35, p < .01); CSF: R = 0.35, p < .01); PET: R = 0.39, p < .01) (see Fig. 3D–F), indicating that the discrepancies between biomarker results and clinically assessed MMSE may also serve as a proxy of cognitive reserve.

Leukoencephalopathy, as assessed with the Fazekas-Score, did not have a significant correlation with baseline cognitive performance (R = 0.08, p = .42).

3.3. Regression model of neuronal injury based cognitive performance

3.3.1. Multiple regression model

Next, we computed a regression model to assess the factors influencing the current cognitive performance. FDG-PET and YoE significantly explained some of the variance in the calculation of MMSEPREDICTED score predicted by the model of neuronal injury biomarkers and covariates (for details see Table 2).

Table 2.

Regression coefficients of the biomarker based model. Regression coefficients, β-values and significance levels of the multiple regression analysis for the calculation of the neuronal injury biomarker based anticipated mini mental status examination.

| Regression coefficient | β | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 20.810 | .000 | |

| FDG-PETvisual | −0.592 | −0.505 | .000 |

| Scheltens-Score | 0.046 | 0.021 | .814 |

| CSFt-tau | 0.0004 | 0.030 | .723 |

| Fazekas score | −0.028 | −0.003 | .967 |

| Years of Education | 0.483 | 0.355 | .000 |

| Gender | −0.499 | −0.058 | .490 |

| Age (y) | 0.002 | 0.004 | .968 |

Using the calculated weighting factors, the individually predicted MMSEPREDICTED score was generated using the following formula:

The multiple regression analysis indicated that 36% of the variance in cognitive impairment was explained by the included parameters, whereas the two significant parameters (FDG-PET + YoE) accounted together for 35% of the variance in a separately calculated regression.

3.3.2. Residualized memory function as a surrogate score of cognitive reserve

We calculated the difference between MMSEOBSERVED and MMSEPREDICTED as a surrogate score of the individual cognitive reserve (ΔMMSE, see Fig. 4). When comparing the individual surrogate score to the published SD of an MMSE test-retest (Tombaugh, 2005), 49.0% of subjects had surrogate score magnitudes exceeding more than one SD (± 2.37) and 15.5% more than two SDs (± 4.74).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of individual discrepancies between the clinical and calculated cognitive performance. The discrepancy in mini mental status examination (MMSE) values (ΔMMSE) is illustrated by a waterfall plot representing the proposed surrogate score for individual cognitive reserve. ± 1 standard deviation (SD) illustrated by black dashed line, and ± 2 SD illustrated by grey dashed line are provided as previously published for MMSE test-retest studies.

Importantly, age had no impact on the observed distribution of surrogate scores of cognitive reserve (R = 0.00, p = .99.; see Supplement Figure 3).

3.4. Prediction of individual cognitive decline by neuronal injury based residualized memory function

Finally, we asked if the calculated surrogate score for cognitive reserve in the single subject has clinical relevance for predicting disease progression. The mean annual MMSE change (n = 110) was −1.55 (± 2.41). ΔMMSE (β = −0.35, p = .02) and RESPET (β = −0.36, p = .01) indicated a significant negative association with the annual MMSE change upon clinical follow-up (see Fig. 5). ΔMMSE, age, and gender together accounted for accounted for 16% of the variance in annual MMSE change (F(3,107) = 4.0, p = .01, R2 = 0.21, R2Adjusted = 0.16); RESPET, age and gender likewise accounted for 17% of the variance in annual MMSE change (F(3,107) = 4.3, p = .01, R2 = 0.23, R2Adjusted = 0.17). Single RESMRI (β = −0.23, p = .11) and RESCSF (β = −0.23, p = .10) did not show a significant correlation with the annual MMSE change.

Fig. 5.

Correlation between change in MMSE scores to clinical follow-up and biomarker findings. Presented are the correlations of stand-alone regressions residuals (RESMRI, RESCSF, RESPET) of magentic resonance imaging (MRI; A), total-tau in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF; B) and FDG positron emission tomography (PET, C) as well as the surrogate score of cognitive reserve (ΔMMSE; D) with the annual MMSE change during clinical follow-up. Values are presented as residuals (res.) from the regression analysis.

Thus, patients whose present cognition seemed at odds with their manifest signs of neuronal injury by biomarker grading showed worse cognitive deterioration in the clinical follow up. Among single neuronal injury markers, the residuals of FDG-PET indicated the strongest predictive value.

4. Discussion

We demonstrate that neuronal injury biomarker readouts in relation to clinical scoring of cognition can serve to assess the individual cognitive reserve in MCI and AD subjects, which is predictive of future decline. Among the neuronal injury biomarkers, FDG-PET correlated better with clinical scoring by MMSE than did measures of hippocampal atrophy by structural MRI or total-tau by CSF analysis. By creating a composite model based on neuronal injury biomarkers and relevant covariates for AD, we further investigated the manner in which cognitive performance predicted by modelling of biomarker findings differed from the individual clinical observations in many patients. The difference between the two cognitive scores (MMSEOBSERVED and MMSEPREDICTED) represents a surrogate for the individual cognitive reserve. Importantly, this individual cognitive reserve forecasts the cognitive deterioration to follow-up, independent from the extent of cognitive deterioration at baseline.

A range of neuronal injury biomarkers (FDG-PET, MRI, CSFt-tau) are currently recommended to substantiate the working hypothesis of an AD diagnosis (Jack Jr et al., 2016). In previous studies, all three of these biomarkers correlated independently with cognitive performance (Nathan et al., 2017; Forster et al., 2010). Nevertheless, their relationship with the extent of neuronal injury is complex, and has poor agreement within the A/T/N triad of biomarkers (Alexopoulos et al., 2014). This may be due to the distinct aspects of neuronal injury captured by PET, MRI and CSF measurements; whereas FDG-PET primary depicts net synaptic dysfunction, the hippocampal atrophy in MRI indicates region specific neuronal and neuropil loss, and elevated total-tau in CSF is a non-specific marker of different forms of neuronal damage (Jack et al., 2010). Furthermore, current thinking holds that tau pathophysiology precedes onset of hypometabolism or hippocampal atrophy in the course of AD (Jack Jr et al., 2013; Bateman et al., 2012). If so, tau levels in CSF may bear only a transient relationship with the extent of neuronal injury and cognitive decompensation. Nonetheless, current practice recommends all three biomarkers equally for assessment of neurodegeneration/neuronal injury by current AD classification schemes (Jack Jr et al., 2016). Our present data entails the hitherto first head-to-head comparison of FDG-PET, MRI, and CSF biomarkers as predictors of current and future cognitive function in a mixed population of MCI and AD patients. We find that reduced relative FDG uptake in AD-related cortical regions correlated best with MMSE scores, whereas hippocampal atrophy or total tau in CSF showed only a poor agreement. Thus, freestanding FDG-PET is a good predictor for cognitive function in this population, with little additional benefit derived from considering MRI and CSF results. This finding may prove particularly useful in the diagnosis of AD in aphasic or otherwise unresponsive patients (Rogalski et al., 2016). Furthermore, we were able to show that a simple scoring system, based on neuronal injury as depicted by surface projections of FDG-PET, gave equivalent prediction of cognitive function when compared to a semi-quantitative approach. This enables taking the previously vague concept of cognitive reserve into consideration when FDG-PET is used for evaluation of possible AD in clinical routine at tertiary centers.

Many different factors have been shown to influence the individual cognitive reserve of the individual patient. Above all, higher YoE seems to be the best predictor for a higher cognitive reserve (Yoon et al., 2016). Importantly, residuals deriving from separate regression analyses between neuronal injury biomarker results and the clinically observed MMSE correlated significantly with the YoE, indicating that these residuals are indeed a surrogate for the individual cognitive reserve. By implication, the neuronal injury biomarkers can also serve as a surrogate of cognitive reserve, as has already been shown for a larger premorbid brain volume (Perneczky et al., 2010) or greater left frontal cortex connectivity (Franzmeier et al., 2018).

The main objective of this study was to create a model including several established biomarkers for neuronal injury and relevant covariates such as age and YoE to compute the residualized memory function. All of the selected parameters are known to impact independently upon cognitive performance (Nathan et al., 2017; Forster et al., 2010; Defrancesco et al., 2013; Niu et al., 2017; Stern, 2012). Our regression analysis showed that 35.8% of the MMSEPREDICTED variance can be explained by these parameters, but that only FDG-PET and educational attainment contributed significantly to the model. Thus, the present A/T/N triad does not capture all factors relevant to cognitive function in the face of neuronal injury. This result further implies that deviations from predicted cognitive state are not simply a matter of deficiency of the model, but rather that individual factors relating to cognitive reserve impart some temporary protection from the cognitive manifestations of ongoing neuronal injury (Ewers et al., 2013). Furthermore, there are numerous additional factors (e.g. depression, hypothyroidism, vitamin-B12 deficiency) having impact on current cognitive performance, which are not sufficiently represented within the established methods of neuronal injury (Jack Jr et al., 2016). BMI, diabetes, smoking status, alcohol intake, hypertension, ApoE4 status and physical activity have all been identified as contributing factors to cognitive status in a large population-based analysis (Livingston et al., 2017). Additionally, environmental factors such as social support and personality differences regarding social engagement may prove to have some weight (Livingston et al., 2017). Vascular comorbidity is another factor likely to have some bearing on cognition in AD, even though the Fazekas rating of leukoencephalopathy had no significant effect in our model. It may be that cognitive effect due to ischemic brain damage is already captured by FDG-PET.

Clinical MMSE assessments, and the corresponding MMSE scores as predicted by our multifactorial model showed considerable discrepancies of 49.0% (± 1 SD) and 15.5% (± 2 SD) respectively when considered in the light of relative SD reported for MMSE test-retest results in similar populations (Tombaugh, 2005). Thus, the residualized memory function as a proxy of the individual cognitive reserve is subject to a large heterogeneity. In about two thirds of our cases the residualized memory function was positive (Fig. 4), which is consistent with greater sensitivity of our compiled biomarker assessment to signs of cognitive decompensation at early stages of AD (Jack Jr et al., 2013). However, there were numerous instances in our population of patients whose clinical MMSE scores were worse than the model-based predictions. Interestingly, the distribution of these MMSE deviations showed no correlation with the age at baseline. This is consistent with earlier findings that patients with early onset AD and amnestic presentation show a distinct cerebometabolic pattern, but no difference in global glucose consumption compared to patients with late onset AD (Chiaravalloti et al., 2016; Aziz et al., 2017).

Finally, we tested if the cognitive reserve estimated from neuronal injury biomarkers at the single patient level is predictive of clinical course. To this end, we correlated the residualized memory with the cognitive deterioration to clinical follow-up. Strikingly, we observed a significantly faster cognitive deterioration measured by MMSE when the initial residuum was positive. This finding suggests that subjects with higher reserve had already accumulated a greater burden of pathology, which subsequently lead to faster decline over time (Stern, 2009). Together with previous findings suggesting that higher reserve is associated with slower cognitive decline, we propose a biphasic reserve effect, with an initial phase of greater resilience, followed by accelerated decline upon decompensation (Stern, 2009). The baseline clinical MMSE had no impact on this correlation, consistent with heterogeneity of the population with respect to reliance on cognitive reserve. A negative predictive value for further cognitive deterioration has already been shown in a univariate model of neuronal injury biomarkers among MCI subjects (Landau et al., 2010; Yuan et al., 2009). Our new findings show that a multimodal grading of neuronal injury based on all neuronal injury biomarkers and relevant covariates is a good predictor of cognitive reserve and therefore further cognitive decline in MCI and AD subjects, irrespective of their baseline cognitive performance.

The assessment of cognitive reserve in individuals offers the opportunity to select or adjust for the patient's risk for cognitive decline, which may prove useful in the design of upcoming therapeutic trials by increasing the sensitivity for detection of cognition endpoints. Furthermore, by considering different biomarker stages of neuronal injury at baseline of such studies we can reduce bias arising from unequal allocation to placebo and treatment arms.

Among the limitations of this study, we note that the MMSE is a commonly used instrument for detection of cognitive impairment in patients with suspected AD, but it cannot replace detailed neuropsychological testing, and does not represent all aspects of cognitive decline. For this reason, we also administered the CERAD test in most of our subjects, which showed comparable results (see Supplement Figure 1). For facile implementation in a clinical routine, the present calculated grading of neuronal injury is based rather on the MMSE, aiming to provide a standardized, widely accepted index. We focused on covariates that are recommended in the guidelines for supporting the diagnosis of AD, but we were not able to cover the full range of environmental factors, co-morbidities, and ApoE-status, which might have had impact in this analysis. Current standards for diagnosis of AD in living patients call for evidence of Aβ and tau pathology to either CSF analysis or PET (Jack Jr et al., 2016). While p-tau content of CSF was available and positive in virtually all of our cases, we had no comprehensive assessment of Aβ. However, diagnoses of AD were confirmed by long term clinical follow-up, and only those subjects with a confident clinical diagnosis were included in the analysis. By design, a major strength of the study lies in the clinical setting, such that our results and models should be easily translatable to routine clinical scenarios.

5. Conclusion

Biomarkers of neuronal injury can predict the individual cognitive reserve in MCI and AD subjects by assessment of the residualized memory function. Importantly, this concept can be established by simple visual and laboratory read-outs without use of highly sophisticated quantification methods. The established surrogate score of cognitive reserve by neuronal injury biomarkers predicts future cognitive progression at the single patient level and should therefore serve to adjust for heterogeneous clinical progression independent of treatment arm in therapeutic trials.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We note professional editing of the manuscript by Inglewood Biomedical Editing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors do not report conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101949.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Alexopoulos P. Limited agreement between biomarkers of neuronal injury at different stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(6):684–689. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andel R. The effect of education and occupational complexity on rate of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s patients. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2006;12(1):147–152. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706060206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz A.L. Difference in imaging biomarkers of neurodegeneration between early and late-onset amnestic Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2017;54:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett J.W. Determining cut-points for Alzheimer's disease biomarkers: statistical issues, methods and challenges. Biomark. Med. 2012;6(4):391–400. doi: 10.2217/bmm.12.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman R.J. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367(9):795–804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler M.J. A total score for the CERAD neuropsychological battery. Neurology. 2005;65(1):102–106. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000167607.63000.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaravalloti A. Comparison between early-onset and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease patients with amnestic presentation: CSF and (18)F-FDG PET study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Dis. Extra. 2016;6(1):108–119. doi: 10.1159/000441776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daerr S. Evaluation of early-phase [(18)F]-florbetaben PET acquisition in clinical routine cases. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;14:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defrancesco M. Impact of white matter lesions and cognitive deficits on conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34(3):665–672. doi: 10.3233/JAD-122095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(6):614–629. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duzel E., van Praag H., Sendtner M. Can physical exercise in old age improve memory and hippocampal function? Brain. 2016;139(Pt 3):662–673. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewers M. Cognitive reserve associated with FDG-PET in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2013;80(13):1194–1201. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828970c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazekas F. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer’s dementia and normal aging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1987;149(2):351–356. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M.F., Folstein S.E., McHugh P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster S. FDG-PET mapping the brain substrates of visuo-constructive processing in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010;44(7):462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzmeier N. Left frontal hub connectivity delays cognitive impairment in autosomal-dominant and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2018;141(4):1186–1200. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammers A. Three-dimensional maximum probability atlas of the human brain, with particular reference to the temporal lobe. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2003;19(4):224–247. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herholz K. Discrimination between Alzheimer dementia and controls by automated analysis of multicenter FDG PET. Neuroimage. 2002;17(1):302–316. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack C.R., Jr. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack C.R., Jr. A/T/N: an unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology. 2016;87(5):539–547. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack C.R., Jr. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack C.R., Jr. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(1):119–128. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.W., MacFall J.R., Payne M.E. Classification of white matter lesions on magnetic resonance imaging in elderly persons. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;64(4):273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau S.M. Comparing predictors of conversion and decline in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2010;75(3):230–238. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e8b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G.M. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith J.E., Jr. Characterization of novel CSF Tau and ptau biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoshima S. A diagnostic approach in Alzheimer’s disease using three-dimensional stereotactic surface projections of fluorine-18-FDG PET. J. Nucl. Med. 1995;36(7):1238–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J.C. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39(9):1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosconi L. Multicenter standardized 18F-FDG PET diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and other dementias. J. Nucl. Med. 2008;49(3):390–398. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan P.J. Association between CSF biomarkers, hippocampal volume and cognitive function in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI) Neurobiol. Aging. 2017;53:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H. Prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer's disease in Europe: a meta-analysis. Neurologia. 2017;32(8):523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonkwo O.C. Physical activity attenuates age-related biomarker alterations in preclinical AD. Neurology. 2014;83(19):1753–1760. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perneczky R. Head circumference, atrophy, and cognition: implications for brain reserve in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2010;75(2):137–142. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e7ca97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter G.G., Helms M.J., Plassman B.L. Associations of job demands and intelligence with cognitive performance among men in late life. Neurology. 2008;70(19):1803–1808. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000295506.58497.7e. Pt 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed B.R. Measuring cognitive reserve based on the decomposition of episodic memory variance. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 8):2196–2209. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogalski E. Aphasic variant of Alzheimer disease: clinical, anatomic, and genetic features. Neurology. 2016;87(13):1337–1343. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheltens P. Atrophy of medial temporal lobes on MRI in “probable” Alzheimer’s disease and normal ageing: diagnostic value and neuropsychological correlates. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1992;55(10):967–972. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.10.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47(10):2015–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(11):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolppanen A.M. Leisure-time physical activity from mid- to late life, body mass index, and risk of dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(4):434–443.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh T.N. Test-retest reliable coefficients and 5-year change scores for the MMSE and 3MS. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2005;20(4):485–503. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese J. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348(25):2508–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R.S. Participation in cognitively stimulating activities and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Jama. 2002;287(6):742–748. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.6.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon B. Predictive factors for disease progression in patients with early-onset Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49(1):85–91. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Gu Z.X., Wei W.S. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron-emission tomography, single-photon emission tomography, and structural MR imaging for prediction of rapid conversion to Alzheimer disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2009;30(2):404–410. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler-Graham K. Worldwide variation in the doubling time of Alzheimer’s disease incidence rates. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4(5):316–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.05.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material