Abstract

Introduction

Breastfeeding is the ideal food source for all newborns globally. However, in the era of Human Immune Deficiency Virus (HIV) infection, feeding practice is a challenge due to mother-to-child HIV transmission. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the national prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and mixed feeding practices among HIV positive mothers and its association with counseling and HIV disclosure status to the spouse in Ethiopia.

Methods

We searched all available articles from the electronic databases including PubMed, EMBASE, Google Scholar, and the Web of Science. Moreover, reference lists of the included studies and the Ethiopian institutional research repositories were used. Searching of articles was limited to the studies conducted in Ethiopia and published in English language. We have included observational studies including cohort, cross-sectional, and case-control studies. The weighted inverse variance random effects model was used. The overall variations between studies were checked through heterogeneity test (I2). Subgroup analysis by region was conducted. To assess the quality of the study, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal criteria were employed. Publication bias was checked with the funnel plot and Egger's regression test.

Result

A total of 18 studies with 4,844 participants were included in this study. The national pooled prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and mixed feeding practices among HIV positive mothers were 63.43% (95% CI: 48.19, 78.68) and 23.11% (95% CI: 10.10, 36.13), respectively. In the subgroup analysis, the highest prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding practice was observed in Tigray (90.12%) and the lowest in Addis Ababa (41.92%). Counseling on feeding option with an odds ratio of 4.32 (95% CI: 2.75, 6.77) and HIV disclosure status to the spouse with an odds ratio of 6.05 (95% CI: 3.03, 12.06) were significantly associated with exclusive breast feedings practices.

Conclusion

Most mothers report exclusive breastfeeding, but there are still almost a quarter of mothers who mix feed. Counseling on feeding options and HIV disclosure status to the spouse should be improved.

1. Introduction

About 90% of pediatrics HIV infection is Mother-To-Child Transmission (MTCT), which may occur during pregnancy, delivery, and breastfeeding [1]. The estimated risk of HIV transmission for nonusers of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) was during breastfeeding (5-20%), overall without breastfeeding (15-25%), overall with breastfeeding to six months (20-35%), and overall with breastfeeding to 18-24 months ranging from 30 to 45% [2, 3]. In the recent studies related to the use of antiretroviral (ARV) therapy, reducing the risk of HIV transmission through breastfeeding showed a promising effect [4].

Breastfeeding especially in the first 12 months of life can significantly prevent malnutrition, infectious diseases, and mortality compared to nonbreastfed infants [5, 6]. In low- and middle-income countries, exclusive breastfeeding practice was considered as a major prevention factor for malnutrition [7]. Avoiding breastfeeding can eliminate the risk of mother-to-child HIV transmission in the postnatal period, but mixed and replacement feeding practices were associated with increased infant mortality and morbidity in sub-Saharan Africa countries [8].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline, breastfeeding, especially early initiation, and exclusive breastfeeding were the most critical factors in improving child survival. Moreover, the WHO's global public health direction for all infants is to breastfeed exclusively (EBF) for the first six months and then introduce nutritionally adequate and safe complementary foods while breastfeeding continues for up to 2 years of age or beyond [9, 10]. However, the WHO criteria are rarely met in developing countries and mixed feeding (MF) is common [11, 12]. This may be extremely difficult in case of HIV infected mother [13].

Therefore, the decision on infant feeding practice in the era of HIV is a big challenge for caretakers and health care providers [11, 14]. Even though exclusive breastfeeding is the best choice of feeding option in the first 6 months of the postnatal period, mother-to-child HIV transmission through breastfeeding is a major concern [14, 15]. Such a dilemma can be addressed through effective counseling and by disclosing their HIV status to their families [16, 17]. Counseling on the use of ART, adherence to ART, mother-to-child HIV transmission, feeding option, and importance of disclosing HIV status could enhance the decision on infant feeding options [18–20].

In Ethiopia, studies on infant feeding practice and its predictors among HIV positive mothers have been conducted in different parts of the country with a time variation. But, the results of these studies were inconsistent. Therefore, the aim of this systemic review and meta-analysis is to estimate the national pooled prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and mixed feeding practices among HIV positive mothers and of its association with counseling on feeding option and HIV status disclosure to the spouse in Ethiopia.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

The protocol of this systematic review and meta-analysis has been registered in the International prospective register of systematic review and meta-analysis (Prospero) with a registration number of CRD42018110574.

2.2. Reporting

For reporting of the findings, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline was employed (Additional file 1).

2.3. Databases and Searching Strategies

All available articles were searched in PubMed, Google Scholar, EMBASE, and the Web of Science. Moreover, studies were searched from the reference lists of included studies and the Ethiopian institutional research repositories. Searching was employed using the following searching terms including “infant”, “neonate”, “child”, “infant feedings”, “Infant feeding practices”, “child feeding practices”, “exclusive breastfeeding practices”, “mixed feeding practices”, “HIV”, “Human Immune Deficiency Virus”, “Mother”, “HIV positive mothers”, “Human Immune Deficiency Virus Positive mothers”, “HIV infected mothers”, “HIV exposed infants”, “HIV infected infants”, “predictors”, “factors”, “ barriers”, “risk factors”, “prevalence”, and “Ethiopia”. The search string was developed using “AND” and “OR” Boolean operators. The searching was done from September 10 to October 28/2018. As for the search of articles in PubMed, we used this searching string (Additional file 2).

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies which met the criteria, (1) observational studies including cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort studies, (2) studies that report the prevalence and/or predictors of infant EBF and mixed feeding practices among HIV positive mothers, (3) studies done in Ethiopia, (4) published and unpublished studies at any time, (5) studies that have been written in English language, and 6 studies that reported extractable data to compute the odds ratio of counseling and HIV disclosure status to the spouse, were included in this study. Abstracts, studies without full texts, conference papers, editorials, letters, protocols, program evaluation reports, systematic reviews, trials, and qualitative studies were excluded. Additionally, studies with a high risk of bias/scored less 50% of critical appraisal checklist were excluded.

2.5. Outcome Measurement

2.5.1. Exclusive Breastfeeding

The infant receives only breast milk without any other liquids or solids, not even water, except for oral rehydration solution or drops or syrups of vitamins, minerals, or medicines in the first 6 months [39].

2.5.2. Mixed Feeding

It is providing other liquids and/or foods together with breast milk for the infant within six months of age. This could be water, other types of milk, or any type of solid food [39].

2.6. Study Screening and Selection

In the beginning, all studies retrieved from the databases were imported to EndNote version 7 citation manager. Next, duplicates were checked and removed. Then, two independent authors (GM and CA) screened the title and the abstracts of retrieved articles. The discrepancies between the authors were solved by discussion and consensus. Consequently, two authors (CA and GM) reviewed the full texts and extracted the data. The first author of the article, year of publication, study area, design, population, region, sample size, extractable data that helps to compute odds ratio of counseling and HIV disclosure status to the spouse, prevalence of EBF, and mixed feeding practices were extracted. Any disagreement between investigators was solved by discussion and repeating of the procedures. Consequently, the data were exported to excel spreadsheets for further analysis.

2.7. Quality Assessment

Two independent authors (GM and CA) assessed the quality of the studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal checklist [40]. The JBI critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies was employed (Additional file 3). Any disagreement between reviewers was solved by discussion and consensus.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

To estimate the national pooled prevalence of EBF and mixed feeding practices among HIV positive mothers, a weighted inverse variance random effects model [41] was used. The publication bias was checked by funnel plot and Egger's regression test. The total percentage of variations between studies due to heterogeneity was assessed by I2 statistics [42]. The values of I2, 25%, 50%, and 75% represent low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [42]. The spreadsheet data was exported to Stata version 11 for all statistical analyses. Subgroup analysis by the region was conducted.

2.9. Data Synthesis

First, the national pooled prevalence of EBF and mixed feeding among HIV positive mothers were performed separately. Second, the regional pooled prevalence of EBF and mixed feeding practices were done. Third, the pooled OR of counseling and HIV disclosure status to the spouse was performed separately. To compute OR, primarily, number of EBF and mixed feeding practices among counseled and noncounseled mothers were extracted from the cross tabulation of the included studies. In addition, the number of EBF and mixed feeding practices were also extracted from mothers who disclose/not disclose their status to the spouse. Then, the extracted data was exported from excel spreadsheet to Stata version 11 to analyze the pooled OR of counseling and HIV disclosure status to the spouse. Finally, the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA guideline) was used to report the findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis [43].

3. Result

3.1. Search Results

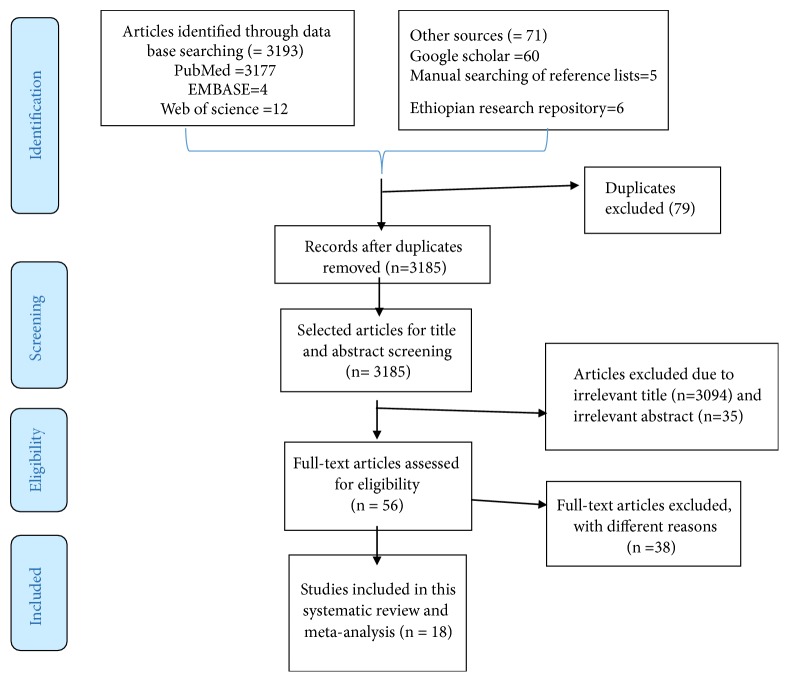

A total of 3264 articles were retrieved from different databases of which 3177 were from PubMed, 60 from Google Scholar, 12 from the Web of Science, 4 from EMBASES, 6 from the Ethiopian university research repositories, and 5 from reference lists of the included studies. However, 79 articles were removed due to duplicates, 3129 due to the irrelevant titles and abstracts, 10 due to the study designs, and 20 due to study areas. Finally, 18 articles were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A PRISMA flow diagram of articles screening and process of selection.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

In this study, a total of 18 studies [21–38] with a sample size of 4,844 were included. Of which, five studies [22, 23, 30, 33, 35] were conducted in Amhara region, five [25, 26, 31, 34, 38] in Oromia, four [21, 28, 29, 37] in Addis Abeba, two [24, 32] in Tigray, and two [27, 36] in Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Regional State (SNNPRS). All included studies were conducted with cross-sectional study design. The highest prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding practice among HIV positive mothers was reported in Oromia region 96.6% (95% CI: 93.66,99.54) [26] and the lowest in Addis Abeba 13.4% (95% CI: 8.91, 17.89) [37]. The detailed characteristics of the included studies were described in (Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of included studies that reported the prevalence and/predictors of exclusive breast feeding among HIV positive mothers (n=18).

| Author/year of publication | Region | Study design | Study area | Populations | Sample size | No. of outcome | Prevalence (%) | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maru y et al./2009 [21] | Addis Ababa | Cross-sectional | Addis Ababa | Young infant | 327 | 100 | 30.6 | Low risk |

| Esubalew F et al./2018 [22] | Amhara | Cross-sectional | Gondar Hospital | 6-18 months | 420 | 107 | 25.5 | Low risk |

| Wakwoya EB et al./2016 [23] | Amhara | cross-sectional | Debre Markos Hospital | < 2 yrs. | 260 | 201 | 77.3 | Low risk |

| Girma Y et al./2014 [24] | Tigray | Cross-sectional | Mekelle Town | < 2 yrs. | 207 | 187 | 90 | Low risk |

| Ejara D et al./2018 [25] | Oromia | Cross-sectional | Bishoftu towns | <18 months | 283 | 242 | 85.5 | Low risk |

| Demssie DB et al./2016 [26] | Oromia | Cross-sectional | Shashemene Referral Hospital | <2 yrs. | 146 | 141 | 96.6 | Low risk |

| Modjo KE et al./2015 [27] | SNNPRS | Cross-sectional | SNNPRS Hospital | <2 yrs. | 436 | 210 | 48.2 | Low risk |

| Wondie T et al./2012 [28] | Addis Ababa | Cross-sectional | Addis Ababa | <12 months | 116 | 65 | 56 | Low risk |

| Demlew MZ et al./2014 [29] | Addis Ababa | Cross-sectional | Addis Ababa | <2 yrs. | 356 | 240 | 68 | Low risk |

| Muluy D et al./2012 [30] | Amhara | Cross-sectional | Gondar health center | <2 yrs. | 209 | 175 | 83.8 | Low risk |

| Bekere A et al./2014 [31] | Oromia | Cross-sectional | West Oromia | 0-6 months | 118 | 85 | 72 | Low risk |

| G/Hiwot A et al./2014 [32] | Tigray | Cross-sectional | central zone | <2 yrs. | 219 | 198 | 90.4 | Low risk |

| Ali Y/2015 [33] | Amhara | Cross-sectional | Wollo Zone | 2-11 months | 373 | 279 | 74.8 | Low risk |

| Hailu C/2005 [34] | Oromia | Cross-sectional | Jima town | 12 months | 643 | 86 | 13.4 | Low risk |

| Tadese F/2017 [35] | Amhara | Cross-sectional | Bahir Dar town | 12 months | 230 | 173 | 75.2 | Low risk |

| Mengstie A et al./2015 [36] | SNNPRS | Cross-sectional | SNNPRS hospital | <2 yrs. | 87 | 49 | 56.3 | Low risk |

| Mebratu T/2014 [37] | Addis Ababa | Cross-sectional | Addis Ababa city | 12 months | 221 | 30 | 13.4 | Low risk |

| Ketema Z/2016 [38] | Oromia | Cross-sectional | Adama health facility | 12 months | 193 | 164 | 84.7 | Low risk |

Note: outcome refers to the number of HIV positive mothers who exclusively breastfeed.

3.3. Quality of Included Studies

All studies [21–38] were assessed with the JBI quality appraisal checklist for cross-sectional studies [40], and none of them were excluded after assessment (Additional file 4).

3.4. Meta-Analysis

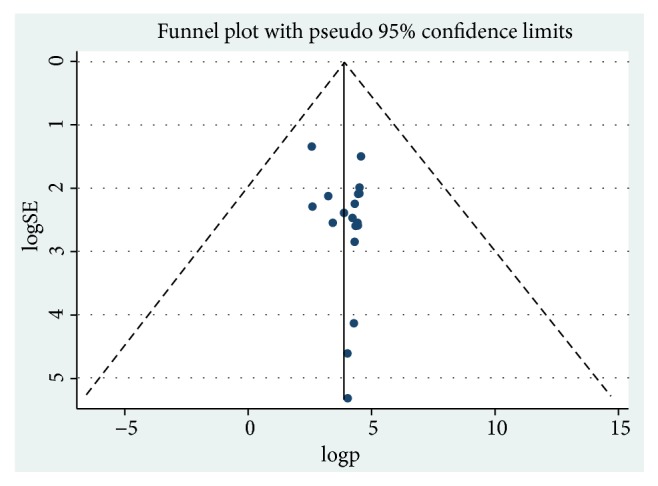

Publication bias was not observed as the funnel plot was symmetrical with visual inspection, and Egger's test value was 0.32 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Funnel plot for publication bias, logp, or LNP(log of proportion) represented in the x-axis and standard error of log proportion in the y-axis.

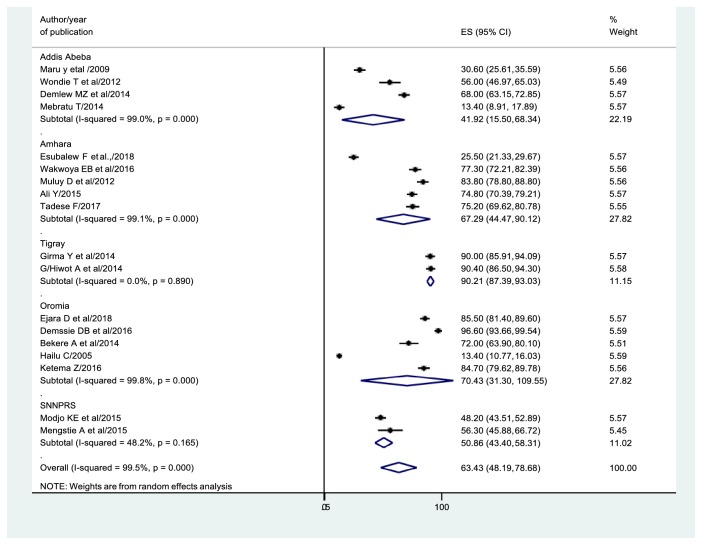

3.5. Prevalence of Exclusive Breastfeeding Practices

On the whole, 18 studies [21–38] were considered to estimate the national prevalence of EBF. Consequently, the overall pooled prevalence of EBF in the current study was 63.43% (95% CI: 48.19, 78.68) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the prevalence EBF with 95% CI. The midpoint and the length of each segment showed the prevalence and 95% CI, respectively. The diamond shape showed the combined prevalence of each region.

In the subgroup analysis by the region, the highest prevalence of EBF practices was observed in Tigray 90.12% (95% CI: 87.39, 93.03), and the lowest in Addis Ababa 41.92% (95% CI: 15.50, 68.34). Moreover, the prevalence of EBF practices in other regions includes Oromia (70.43%), Amhara (67.29%), and SNNPRS (50.88%). The detailed descriptions were illustrated in Figure 3.

3.6. Characteristics of Studies That Report Mixed Feeding Practices

Out of 18 studies, fifteen [21, 23–27, 30–38] were reporting the prevalence of mixed feeding practices, of which two [21, 37] were conducted in Addis Abeba, four [23, 30, 33, 35] in Amhara region, two [24, 32] in Tigray, five [25, 26, 31, 34, 38] in Oromia, and two [27, 36] in SNNPRS (Table 2).

Table 2.

General characteristics of included studies that reported the prevalence and/predictors of mixed feeding practices among HIV positive mothers (n=15).

| Author/year of publication | Study area | Region | Study design | Population | Sample size | Number of outcome | Prevalence (%) | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maru y et al./2009 [21] | Addis Ababa | Addis Ababa | Cross-sectional | Young infant | 327 | 50 | 15.30 | Low risk |

| Wakwoya EB et al./2016 [23] | Debre Markos Hospital | Amhara | Cross-sectional | < 2 yrs. | 260 | 37 | 14.20 | Low risk |

| Girma Y et al./2014 [24] | Mekelle Town | Tigray | Cross-sectional | < 2 yrs. | 207 | 13 | 6.30 | Low risk |

| Ejara D et al./2018 [25] | Bishoftu town | Oromia | Cross-sectional | <18 months | 283 | 23 | 8.30 | Low risk |

| Demssie DB et al./2016 [26] | Shashemene Referral Hospital | Oromia | Cross-sectional | <2 yrs. | 146 | 1 | 0.70 | Low risk |

| Modjo KE et al./2015 [27] | SNNPRS Hospital | SNNPRS | Cross-sectional | <2 yrs. | 436 | 151 | 34.60 | Low risk |

| Muluy D et al./2012 [30] | Gondar H/c | Amhara | Cross-sectional | <2 yrs. | 209 | 22 | 10.50 | Low risk |

| Bekere A et al./2014 [31] | West Oromia | Oromia | Cross-sectional | 0-6 months | 118 | 29 | 24.60 | Low risk |

| G/Hiwot A et al./2014 [32] | Central zone | Tigray | Cross-sectional | <2 yrs. | 219 | 13 | 5.90 | Low risk |

| Ali Y/2015 [33] | Wollo Zone | Amhara | Cross-sectional | 2-11 months | 373 | 44 | 11.80 | Low risk |

| Hailu C/2005 [34] | Jima town | Oromia | Cross-sectional | <12 months | 643 | 521 | 81.00 | Low risk |

| Tadese F/2017 [35] | Bahir Dar town | Amhara | Cross-sectional | <12 months | 230 | 25 | 10.90 | Low risk |

| Mengstie A et al./2015 [36] | SNNPRS hospital | SNNPRS | Cross-sectional | <2 yrs. | 87 | 31 | 35.60 | Low risk |

| Mebratu T/2014 [37] | Addis Ababa city | Addis Ababa | Cross-sectional | 12 months | 221 | 180 | 81.50 | Low risk |

| Ketema Z/2016 [38] | Adama health facility | Oromia | Cross-sectional | 12 months | 193 | 12 | 6.30 | Low risk |

Note: outcome refers to the number of HIV positive mothers who practiced mixed feedings.

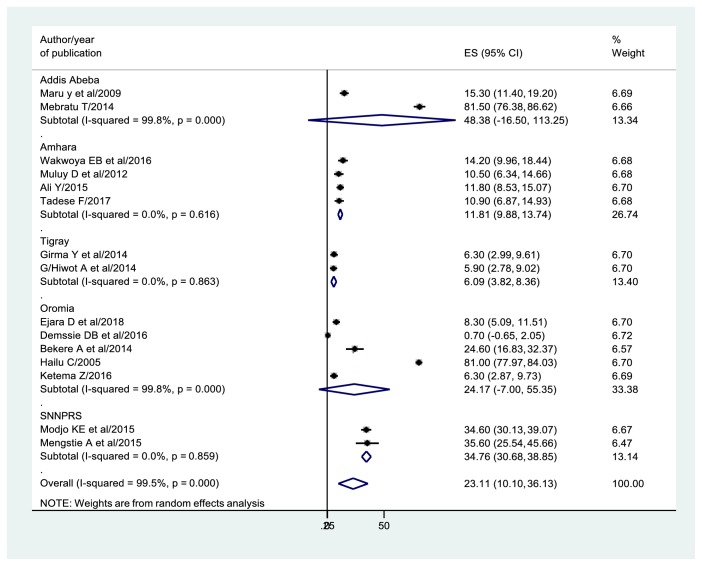

3.7. Prevalence of Mixed Feeding Practices

In this study, the overall pooled prevalence of mixed feeding practices among HIV positive mothers was 23.11% (95% CI: 10.10, 36.13) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the prevalence of mixed feeding by region with 95% CI. The midpoint and the length of each segment revealed the prevalence and 95% CI of each study whereas the diamond shape showed the combined prevalence.

In the subgroup analysis by the region, the highest pooled prevalence of mixed feeding was observed in Addis Ababa (48.38%), followed by SNNPRS (34.76%), Oromia (24.17%), Amhara (11.81%), and Tigray (6.09%) (Figure 4).

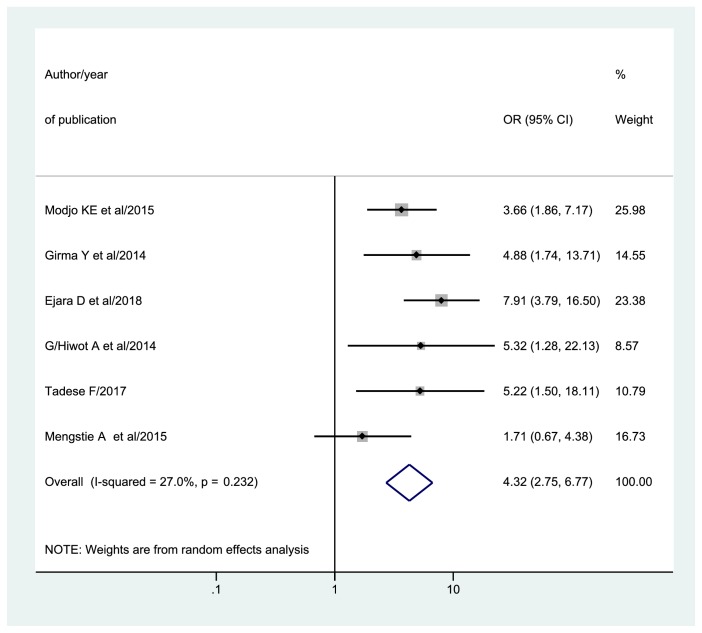

3.8. The Association between Counseling and Exclusive Breastfeeding Practices

The studies reported different predictors which significantly associated with infant feeding practices of HIV positive mothers of which, counseling on feeding options is the most frequently reported predictors.

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, six studies [24, 25, 27, 32, 35, 36] reported data that help to calculate an odds ratio of counseling on feeding options. Consequently, the association between EBF and counseling on feeding options was determined. Therefore, the overall pooled odds ratio of exclusive breastfeeding practices among HIV positive mothers who had been counseled on feeding options was 4.32 (95% CI: 2.75, 6.77) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of odds ratio of counseling with 95%CI. The midpoint and the length of each segment revealed OR and 95%CI. The diamond shape showed pooled OR.

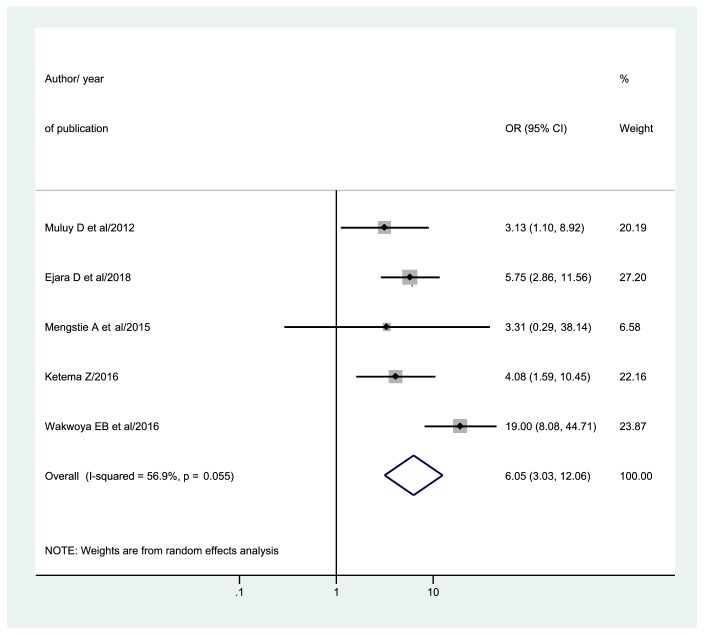

3.9. The Association between HIV Disclosure to the Spouse and EBF Practices

Five studies [23, 25, 30, 36, 38] reported extractable data for determining the association between HIV status disclosure to the spouse and exclusive breastfeeding practices. Following that, the overall pooled odds ratio (OR) of exclusive breastfeeding practices among HIV positive mothers who disclosed their HIV status to the spouse was 6.05 (95% CI: 3.03, 12.06) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of odds ratio of HIV disclosure status to the spouse with 95% CI. The midpoint and the length of each segment showed OR and 95% CI, respectively. The diamond shape revealed pooled OR.

4. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the national pooled prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and mixed feeding practices and of its association with counseling and HIV disclosure status to the spouse. The overall pooled prevalence of EBF and mixed feeding practices among HIV positive mothers were 63.43% and 23.11%, respectively. Counseling on feeding options and HIV disclosure status to the spouse were significantly associated with exclusive breast feedings practices.

Regarding the prevalence of EBF practices, the result is in line with the study conducted in Kenya (57.7%) [44], Zambia (40%) [45], Sudan (78%) [46], and Southwestern Nigeria (61%) [47]. On the other hand, the result was higher than two studies conducted in Uganda (24%) [48] and (28%) [49], four studies conducted in South Africa, (35.6%) [50], (30.9%) [50, 51] and (11%) [52], Nigeria (9%) [53], and India (30.6%) [54], but lower than that of the study conducted in Kenya (92%) [55]. The possible reason for the high prevalence of EBF in Ethiopia could be (1) breastfeeding in Ethiopia was considered as a cultural practice and (2) according to EDHS 2016 report, there was high fear of stigma and discrimination in the region except in Addis Ababa [56]. Different studies revealed that high fear of stigma and discrimination was significantly associated with high odds of EBF. For instance, one study conducted in Nigeria revealed a high proportion of mothers practiced exclusive breastfeeding due to fear of stigmatization [57]. (3) The third reason for EBF may be low socioeconomic status in Ethiopia; in this case, the only option of feeding will be breast milk for their infant.

On the other hand, parents from other countries perceived that breast milk alone is not an enough source of nutrition. For instance, in South Africa, there was a belief that breast milk is not enough for their infant [58]. In addition, another study in South Africa revealed that about one-third of the women were introducing other fluids within the first 3 days after birth [59]. Similarly, one study conducted in Uganda revealed that there was a belief that EBF as “not enough” or “even harmful” [60].

Concerning mixed feeding practices, the result was in line with the study done in Nigeria (13%) [47] but lower than the study done in India (43%) [61] and South Africa (61%) [52]. On the other hand, it was higher than studies conducted in southwest Nigeria (4%) [53] and Sudan (4%) [46].

Subgroup analysis revealed that there was a significant variation among regions. In subgroup analysis, the lowest prevalence of EBF practices was observed in Addis Ababa. This variation could be (1) low fear of discrimination in Addis Ababa compared to other regions. According to the 2016 EDHS report, in Addis Ababa there was low fear of discrimination (18%) [56]. This could result in early switching of breastfeeding to formula milk since there will be minimal fear of discrimination when they stop breastfeeding. For instance a study done in Nigeria revealed that a high fear of stigmatization was significantly associated with a high prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding practices [47]. (2) Another possible justification could be the economic status of mothers. As compared to other regions, in Addis Ababa, there is a good living condition in terms of the accessibility of a variety of foods for the infant. One study revealed that regions with lack of funds and poor hygienic conditions were reasons for exclusive breastfeeding [61]. Another study also showed that cultural attitudes, levels of income, and affordability of food were significantly associated with EBF [62].

Concerning predictors, in this systematic review and meta-analysis, HIV positive mothers who have been counseled on feeding options were exclusively breastfeeding their infants nearly four times more likely as compared to none counseled mothers. This finding was in line with the study done in Nigeria [47, 63], Lesotho [64], and Botswana [65].

This was due to the fact that counseled mothers on feeding options would have higher knowledge and awareness on feeding options and PMTCT compared to noncounseled mother [65]. In addition, they would have knowledge of the benefits of EBF and the risks of mixed feedings.

Another factor that was significantly associated with EBF practice was HIV disclosure to the spouse. Even though there are a number of predictors of EBF practices, HIV status disclosure to the spouse is prominent. In this study, we found that the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding practices among HIV positive mothers who disclose their status to the spouse was nearly six times more likely than mothers who did not disclose their status. This finding was in agreement with the study conducted in Nigeria [63]. The possible reason would be if mothers disclose their HIV status to the spouse, she might get a good family care. For instance, decreased workload, nutritional support, good adherence to ART, and exclusive breastfeeding encouragement were some of the reasons for disclosure [66–68]. Moreover, disclosing HIV status to the spouse prevents mixed feeding [69]. This is due to the fact that HIV positive mothers who disclose their status to the partner will get adequate care, support, and time for breastfeeding [70].

5. Conclusion

Most mothers report exclusive breastfeeding, but there are still almost a quarter of mothers who mix feed. Counseling on feeding options and HIV disclosure to the spouse were significantly associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices. Therefore, counseling on feeding options and HIV disclosure status to the spouse should be strengthened.

5.1. Limitation of the Study

Even though the this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the national prevalence of EBF and mixed feeding practices and its association with counseling and HIV disclosure status, it is not representative for all regions as data was not found in Afar, Somali, Benshangul-Gumuz, Gambella, and Harari. This study also did not determine other factors.

Acknowledgments

Our special gratitude goes to the authors of included studies who helped us to do this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- ANC:

Antenatal Care

- AOR:

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- ART:

Antiretroviral Therapy

- EBF:

Exclusive Breastfeeding

- HIV:

Human Immune Deficiency Virus

- MF:

Mixed Feeding

- PMTCT:

Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission

- SNNPRS:

Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region State.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during study are included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Getaneh Mulualem Belay conceived and designed the study. Getaneh Mulualem Belay and Chalachew Adugna Wubneh established the search strategy, extracted the data, assessed the quality of included studies, did the analysis, and finally wrote the review. All authors had prepared the manuscript. Finally, the authors read, modified, and agreed on the final prepared manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

Additional File 1. File name: Additional file 1. Title: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline check list. Description of data: the PRISMA guideline contains a 26 checklist items which had been used to report the finding of this study.

Additional File 2. File name: Additional file 2. Title: PubMed searching string. Description of data: To retrieve articles from the electronic databases, we have used searching terms which are attached as additional file 2.

Additional File 3. File name: Additional file 3. Title: JBI critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies. Description of data: 8 items of JBI critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies were employed to assess the quality of included study.

Additional File 4. File name: Additional file 4. Title: quality assessment result. Description of data: critical appraisal result of 18 studies.

References

- 1.Fedearl Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Country Progress Report on the HIV Response, 2014. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health. Guideline for Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV in Ethiopia: Federal HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office. Federal Ministry of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health. National Consolidated Guidelines for Comprehensive HIV Prevention, Care and Treatment. Vol. 3. Federal HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office, Federal Ministry of Health, Federal Ministry of Health: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chikhungu L. C., Bispo S., Rollins N., Siegfried N., Newell M.-L. HIV‐free survival at 12–24 months in breastfed infants of HIV‐infected women on antiretroviral treatment. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2016;21(7):820–828. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Victora C. G., Bahl R., Barros A. J. D., et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mbori-Ngacha D., Nduati R., John G., et al. Morbidity and mortality in breastfed and formula-fed infants of HIV-1–infected women: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286(19):2413–2420. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.19.2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chikhungu L., Bispo S., Newell M. Guideline: Updates on HIV And Infant Feeding: The Duration of Breastfeeding, And Support from Health Services to Improve Feeding Practices among Mothers Living with HIV Edn Geneva. World Health Organization; 2016. Postnatal HIV transmission rates at age six and 12 months in infants of HIV-infected women on ART initiating breastfeeding: a systematic review of the literature. Commissioned for the guideline review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinha B., Chowdhury R., Sankar M. J., et al. Interventions to improve breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica. 2015;104:114–134. doi: 10.1111/apa.13127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. Guideline: Updates on HIV And Infant Feeding: The Duration of Breastfeeding, and Support from Health Services to Improve Feeding Practices among Mothers Living with HIV. 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. Guidelines on HIV And Infant Feeding 2010: Principles and Recommendations for Infant Feeding in the Context of HIV And A Summary of Evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leshabari S. C., Blystad A., Moland K. M. Difficult choices: Infant feeding experiences of HIV-positive mothers in northern Tanzania. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS. 2007;4(1):544–555. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2007.9724816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onyango-Makumbi C., Bagenda D., Mwatha A., et al. Early weaning of HIV-exposed uninfected infants and risk of serious gastroenteritis: findings from two perinatal hiv prevention trials in Kampala, Uganda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;53(1):20–27. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bdf68e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UNAIDs. Global HIV/AIDS response: epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access: progress report 2011. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doherty T., Chopra M., Nkonki L., Jackson D., Persson L.-A. A longitudinal qualitative study of infant-feeding decision making and practices among HIV-positive women in South Africa. Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136(9):2421–2426. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.9.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doherty T., Chopra M., Nkonki L., Jackson D., Greiner T. Effect of the HIV epidemic on infant feeding in South Africa: “when they see me coming with the tins they laugh at me”. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2006;84(2):90–96. doi: 10.2471/BLT.04.019448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farquhar C., Mbori-Ngacha D. A., Bosire R. K., Nduati R. W., Kreiss J. K., John G. C. Partner notification by HIV-1 seropositive pregnant women: association with infant feeding decisions. AIDS. 2001;15(6):815–817. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200104130-00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manuela de Paoli M., Manongi R., Klepp K. Counsellors’ perspectives on antenatal HIV testing and infant feeding dilemmas facing women with HIV in Northern Tanzania. Reproductive Health Matters. 2002;10(20):144–156. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(02)00088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madiba S. HIV disclosure to partners and family among women enrolled in prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV Program: implications for infant feeding in poor resourced communities in South Africa. Global Journal of Health Science. 2013;5(4, article 1) doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n4p1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desclaux A., Alfieri C. Counseling and choosing between infant-feeding options: overall limits and local interpretations by health care providers and women living with HIV in resource-poor countries (Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon) Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(6):821–829. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finocchario-Kessler S., Catley D., Thomson D., Bradley-Ewing A., Berkley-Patton J., Goggin K. Patient communication tools to enhance ART adherence counseling in low and high resource settings. Patient Education and Counseling. 2012;89(1):163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maru Y., Haidar J. Infant feeding practice of HIV positive mothers and its determinants in selected health institutions of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development. 2009;23(2) doi: 10.4314/ejhd.v23i2.53225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esubalew F., Atenafu A., Abebe Z. Feeding practices according to the WHO- recommendations for HIV exposed children in northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. 2018;28:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakwoya E. B., Zewudie T. A., Gebreslasie K. Z. Infant feeding practice and associated factors among HIV positive mothers in Debre Markos Referral Hospital East Gojam zone, North West Ethiopia. Pan African Medical Journal. 2016;24 doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.300.8528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Girma Y., Aregay A., Biruh G. Infant feeding practice and associated factors among hiv positive mothers enrolled in governmental health facilities in Mekelle Town, Tigray Region, North Ethiopia. Journal of HIV/AIDS and Infectious Diseases. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ejara D., Mulualem D., Gebremedhin S. Inappropriate infant feeding practices of HIV-positive mothers attending PMTCT services in Oromia regional state, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2018;13(1, article 37) doi: 10.1186/s13006-018-0181-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demissie D. B., Tadesse F., Bezabih B., et al. Infant feeding practice and associated factors of hiv positive mothers attending prevention of mother to child transmission and antiretroviral therapy clinics in shashemene referal hospital. Journal of Health, Medicine and Nursing. 2016;30 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Modjo K. E., Amanta N. W. Attitude and practice towards exclusive breast feeding and its associated factors among HIV positive mothers in Southern Ethiopia. American Journal of Health Research. 2015;3(2):105–115. doi: 10.11648/j.ajhr.20150302.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wondie T., Worku B. Exclusive breastfeeding and repkacemnt feeding onmorbidityand mortality in HIV exposed infants at one year age in tikur anbessa specialized hospital. Ethiopian Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health. 2012;8(8):52–59. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demelew M. Z., Abdeta G. Assessment of exclusive breastfeeding practices among HIV positive women in Addis Ababa. African Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 2014;8(1):14–20. doi: 10.12968/ajmw.2014.8.1.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muluye D., Woldeyohannes D., Gizachew M., Tiruneh M. Infant feeding practice and associated factors of HIV positive mothers attending prevention of mother to child transmission and antiretroviral therapy clinics in Gondar Town health institutions, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1, article 240) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bekere A., Garoma W., Beyene F. Exclusive breastfeeding practices of HIV positive mothers and its determinants in selected health institution of West Oromia, Ethiopia. Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences. 2014;4(6, article 1) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hiwot A. G., Silassie K. H., Mirutse G. M., et al. Infant feeding practice of HIV positive mothers and its determinants in public health institutions in central zone, Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia. International Journal of Pharma Sciences and Research (IJPSR) 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali Y., Reddy P. S. Assessment of infant feeding practices among HIV positive mothers receiving ARV/ART and HIV status of their infants with its determinants in South and North Wollo Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. International Journal of Scientific Research. 2015;4(2) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hailu C. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude & Practice among Mothers about Vct And Feeding of Infants Born to Hiv Positive Women in Jimma Town, Ethiopia. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sendo E. G., Mequanint F. T., Sebsibie G. T. Infant feeding practice and associated factors among hiv positive mothers attending art clinic in governmental health institutions of bahir dar town. J AIDS Clin Res. 2018;9(1):p. 755. Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Astewaya M., Tirhas T., BogaleTessema . Assessment of factors associated with infant and young child feeding practices of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive mothers in selected hospitals of Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples Region (SNNPR) Ethiopia. Journal of AIDS and HIV Research. 2016;8(6):80–92. doi: 10.5897/JAHR2015.0355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mebratu T. Assessement of Kap of Hiv Positive Mothers on Vct and Infant Feeding in Akaki Kaliti, Addis Abeba, Ethiiopia. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ketema Z. Exclusive Breast Feeding Practices and Associated Factors among HIV Positive Women in Public Health Facilities of Adama Town, Ethiopia. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unicef Whoa. Updates on HIV and Infant Feeding. World health organization and Unicef; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Institute J. B. The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools for Use in JBI Systematic Reviews Checklist. Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute North Adelaide; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41.DerSimonian R., Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2007;28(2):105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higgins J. P. T., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J., Altman D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liberati A., Altman D. G., Tetzlaff J., et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.e1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Omwenga J. M., MurithiNjiru J., HamsonOmaeNyabera Determinants of infant feeding practices among HIV-positive mothers attending comprehensive care clinic at ahero sub-county hospital. International Journal of Novel Research in Healthcare and Nursing. 2016;3(3):127–135. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banda J., Edgar Infant feeding practices of hiv positive mothers in lusaka district. The University of Zambia. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lasuba A. Y. Infant feeding methods among HIV-positive mothers in Yei County, South Sudan. South Sudan Medical Journal. 2016;9(3):56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aishat U., David D., Olufunmilayo F. Exclusive breastfeeding and HIV/AIDS: a crossectional survey of mothers attending prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV clinics in southwestern Nigeria. Pan African Medical Journal. 2015;22(1) doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.21.309.6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fadnes L. T., Engebretsen I. M., Wamani H., Semiyaga N. B., Tylleskär T., Tumwine J. K. Infant feeding among HIV-positive mothers and the general population mothers: comparison of two cross-sectional surveys in Eastern Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1, article 124) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fadnes L. T., Engebretsen I. M., Wamani H., Wangisi J., Tumwine J. K., Tylleskär T. Need to optimise infant feeding counselling: a cross-sectional survey among HIV-positive mothers in Eastern Uganda. BMC Pediatrics. 2009;9(1, article 2) doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ladzani R., Peltzer K., Mlambo M. G., Phaweni K. Infant-feeding practices and associated factors of HIV-positive mothers at Gert Sibande, South Africa. Acta Paediatrica. 2011;100(4):538–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.02080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ellis K. L. Determinants Of Infant Feeding Practices Of Hiv-Positive And Hiv-Negative Mothers In Pretoria, South Africa, 2013. Yale University, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2013. 1569181 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghuman M., Saloojee H., Morris G. Infant feeding practices in a high HIV prevalence rural district of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;22(2):74–79. doi: 10.1080/16070658.2009.11734222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.David A. N., Ezechi O. C., Aghahowa E., et al. Infant feeding practices of HIV positive mothers in Lagos, South-western Nigeria. Malaysian Journal of Nutrition. 2017;23(2):253–262. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shital M. S., Joshi S. G., Waghmare V. Infant feeding practice of HIV positive mothers and its determinants. Asian Academic Research Journal of Multidisciplinar. 2016;3(4) [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sint T. T., Lovich R., Hammond W., et al. Challenges in infant and young child nutrition in the context of HIV. AIDS. 2013;27:S169–S177. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.EDHS EDHS. Health survey. Key Indicators Report. 2016

- 57.Aishat U., Olufunmilayo F., David D., Gidado S. Factors influencing infant feeding choices of HIV positive mothers in Southwestern, Nigeria. American Journal of Public Health Research. 2015;3(5A):72–79. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaponda A., Goon D. T., Hoque M. E. Infant feeding practices among HIV-positive mothers at Tembisa hospital, South Africa. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine. 2017;9(1):1–6. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1278.a1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doherty T., Sanders D., Jackson D., et al. Early cessation of breastfeeding amongst women in South Africa: an area needing urgent attention to improve child health. BMC Pediatrics. 2012;12(1, article 105) doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Engebretsen I. M. S., Moland K. M., Nankunda J., Karamagi C. A., Tylleskär T., Tumwine J. K. Gendered perceptions on infant feeding in Eastern Uganda: continued need for exclusive breastfeeding support. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2010;5, article 13 doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suryavanshi N., Jonnalagadda S., Erande A. S., et al. Infant feeding practices of HIV-positive mothers in India. Journal of Nutrition. 2003;133(5):1326–1331. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wapang'ana G. Assessment of factors influencing infant feeding practices among HIV positive mothers in Rongo District. Western Kenya: School of Public Health Kenyatta University PubMed| Google Scholar; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ikeako L., Ezegwui H., Nwafor M., Nwogu-Ikojo E., Okeke T. Infant Feeding practices among HIV-positive women in Enugu, Nigeria. British Journal of medicine and Medical Research. 2015;8(1):61–68. doi: 10.9734/BJMMR/2015/16980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olorunfemi S. O., Dudley L. Knowledge, attitude and practice of infant feeding in the first 6 months among HIV-positive mothers at the Queen Mamohato Memorial hospital clinics, Maseru, Lesotho. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine. 2018;10(1) doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ndubuka J., Ndubuka N., Li Y., Marshall C. M., Ehiri J. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding infant feeding among HIV-infected pregnant women in Gaborone, Botswana: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2013;3(11) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003749.e00374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gari T., Habte D., Markos E. HIV positive status disclosure among women attending art clinic at Hawassa University Referral Hospital, South Ethiopia. East African Journal of Public Health. 2010;7(1):87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Przybyla S. M., Golin C. E., Widman L., Grodensky C. A., Earp J. A., Suchindran C. Serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV: examining the roles of partner characteristics and stigma. AIDS Care. 2013;25(5):566–572. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.722601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hosseinzadeh H., Hossain S. Z., Bazargan-Hejazi S. Perceived stigma and social risk of HIV testing and disclosure among Iranian-Australians living in the Sydney metropolitan area. Sexual Health. 2012;9(2):p. 171. doi: 10.1071/SH10111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Atuyambe L. M., Ssegujja E., Ssali S., et al. HIV/AIDS status disclosure increases support, behavioural change and, HIV prevention in the long term: a case for an Urban Clinic, Kampala, Uganda. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14(1) doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deribe K., Woldemichael K., Wondafrash M., Haile A., Amberbir A. Disclosure experience and associated factors among HIV positive men and women clinical service users in southwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional File 1. File name: Additional file 1. Title: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline check list. Description of data: the PRISMA guideline contains a 26 checklist items which had been used to report the finding of this study.

Additional File 2. File name: Additional file 2. Title: PubMed searching string. Description of data: To retrieve articles from the electronic databases, we have used searching terms which are attached as additional file 2.

Additional File 3. File name: Additional file 3. Title: JBI critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies. Description of data: 8 items of JBI critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies were employed to assess the quality of included study.

Additional File 4. File name: Additional file 4. Title: quality assessment result. Description of data: critical appraisal result of 18 studies.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during study are included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.