Abstract

Previous studies of Zika virus (ZIKV) pathogenesis have focused primarily on virus-driven pathology and neurotoxicity, as well as host-related changes in cell proliferation, autophagy, immunity, and uterine function. We now hypothesize that ZIKV pathogenesis arises instead as an (unintended) consequence of host innate immunity, specifically, as the side effect of an otherwise well-functioning machine. The hypothesis presented here suggests a new way of thinking about the role of host immune mechanisms in disease pathogenesis, focusing on dysregulation of post-transcriptional RNA editing as a candidate driver of a broad range of observed neurodevelopmental defects and neurodegenerative clinical symptoms in both infants and adults linked with ZIKV infections. We collect and synthesize existing evidence of ZIKV-mediated changes in expression of Adenosine Deaminases Acting on RNA (ADARs), known links between abnormal RNA editing and pathogenesis, as well as ideas for future research directions, including potential treatment strategies.

Keywords: Zika virus (ZIKV), Congenital Zika syndrome (CZS), Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS), Innate immunity, RNA editing, Adenosine Deaminases Acting on RNA (ADAR) editing

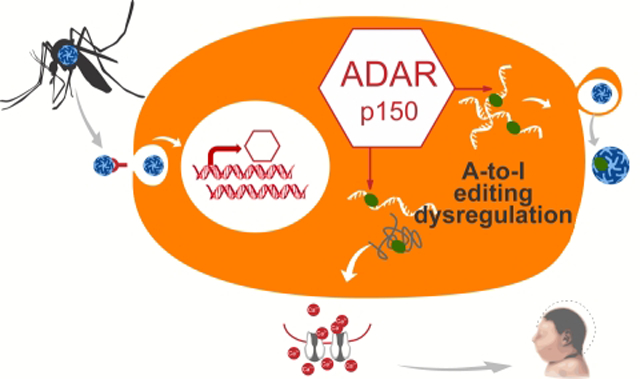

Graphical Abstract

Adenosine Deaminases Acting on RNA (ADAR) enzymes are key regulators of mRNA, and thus, protein diversity in humans. We outline how Zika virus infections can lead to ADAR editing dysregulation, and thereby, the neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative pathologies of congenital Zika and Guillain-Barre syndromes, and how to test this hypothesis.

Introduction: ZIKV-mediated Pathogenesis

Discovery of a link between Zika virus (ZIKV) infection in pregnancy and infantile microcephaly in 2015 [1] propelled this flavivirus from relative obscurity into the spotlight. ZIKV continues to present a significant hazard to human health [2], primarily because of profound disability in infants born with congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) [3]. Nor are adults immune: following ZIKV infection, some adults develop Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) [4], a debilitating peripheral neuropathy that is potentially life-threatening and costly to treat [5]. There is currently no available vaccine for ZIKV nor are antiviral treatments available [2]. Prevention is also challenging, given the diverse routes of infection (via mosquitoes as well as via human-to-human sexual and vertical transmission). Therefore, insights into the mechanisms behind ZIKV-associated pathogenesis are critical to the development of treatments that can ameliorate potential ZIKV sequelae.

What do we know so far about ZIKV-mediated pathogenesis? On the one hand, most ZIKV infections in adults are benign and self-limiting [6], as many as 80% being asymptomatic [7]. The majority of acute ZIKV infections in children appear to be similarly mild in nature [8]. However, this pattern of asymptomatic infection is problematic in itself, as lack of awareness of infection could increase rates of sexual transmission, for example. And, the risk of neurodevelopmental fetal defects appears to be similar between symptomatic and asymptomatic pregnant women [9].

During pregnancy, ZIKV poses a substantial risk of fetal neurodevelopmental defects (up to ~15% of pregnancies [10]), and increased risk of fetal demise [11]. CZS encompasses a broad range of abnormalities beyond microcephaly [12], including ocular [13] and auditory defects [14]. The full spectrum of CZS is still being elucidated, coupled with concerns that ZIKV-related outcomes are underreported, particularly when ZIKV infections result in later onset of developmental delays and learning disabilities without visible microcephaly [15], or includes other systemic abnormalities that manifest postnatally [16]. Likewise, the long-term consequences of in utero ZIKV infections remain poorly understood, particularly in infants lacking visible symptoms of CZS.

ZIKV infections have also been linked to severe neurotoxicity in some adults, including GBS, which is one of the leading causes of acute flaccid paralysis worldwide [17]. Early GBS diagnosis remains a challenge, particular in atypical presentations and/or pediatric patients [18]. As we learn more about ZIKV, the list of neurological and other consequences of ZIKV infection in adults and children – including meningoencephalitis, paresis, and vasculitis - keeps growing [19] [13].

Since 2015, major efforts have focused on delineating ZIKV biology and the mechanisms of ZIKV-associated pathogenesis. Below we highlight some of these advances. It should be noted that these mechanisms are not necessarily mutually exclusive and may indeed act synergistically.

The first category of mechanisms takes advantage of evolutionary and reverse genetics approaches [20] to identify viral mutations that may result in increased fetal pathogenicity. Among these are specific amino acid substitutions, for example, the serine to asparagine (S139N) substitution in the prM protein [21] that increases ZIKV infectivity for neural progenitor cells [22]; as well as genetic differences among lineages that span multiple residues and influence viral biology, including replication and cytopathicity [23] [20] [24] [25]. Unique changes are also observed in the non-coding regions, e.g., addition of an extra 3’ UTR binding site for Musashi-1, an important regulator of translation in neural stem cells, in the Asian ZIKV lineage, which in turn may disrupt its binding to endogenous targets [26].

ZIKV pathogenicity has also been linked with viral interference with various aspects of host biology [27], including disruption of mitotic processes [28], e.g., via centrosome dysfunction or induction of cell death [29] [30], induction of autophagy [31], and inhibition of host immune responses [32], e.g., STAT2 or RIG-I-like receptors [33]. Molecular mimicry between host and virus has also been invoked, where numerous short peptide sequences from human proteins, including those involved in microcephaly or other neurological conditions, are shared with ZIKV-derived ones [34] [33]. Finally, because of the ability of ZIKV to cross the placental barrier [35], fetal pathogenesis has also been linked with placental inflammatory response [36] [35] and increased in utero levels of cortisol [37].

Another category of mechanisms invokes adaptive immunity as a possible driver of ZIKV pathogenesis. ZIKV pathogenesis may be linked to prior exposure and/or co-infection with other viruses [38], including dengue (DENV), another flavivirus, and chikungunya (CHIKV), an alphavirus. Sequence and structural similarity between ZIKV and DENV proteins underlies their substantial antigenic overlap, which can lead to neutralizing antibodies against one virus being cross-reactive, so that subsequent infection by another virus is enhanced [39] [40]. Referred to as antibody-dependent enhancement, this results in increased infection of cultured human placental macrophages, as well as increased viremia in human placental explants [41]. Recent large-scale observational analysis showed no evidence of changes in microcephaly risk due to concurrent exposure to DENV or CHIKV [42].

Despite these discoveries, our understanding of ZIKV-mediated pathogenesis remains limited, in part because the symptoms and sequelae of ZIKV infection are broad and disparate, spanning from asymptomatic and subclinical to major birth defects in infants, as well as severe adverse outcomes in some adults. We now propose a novel hypothesis that can help explain this multitude of diverse ZIKV infection outcomes both pre- and post-natally. While it requires experimental validation, this hypothesis is firmly grounded in evidence from multiple areas of study, and allows us to make connections between previously un-connectable observations. It also enables us to generate new, testable hypotheses that may enable development of effective treatment and prevention strategies.

Hypothesis: Connecting the Dots

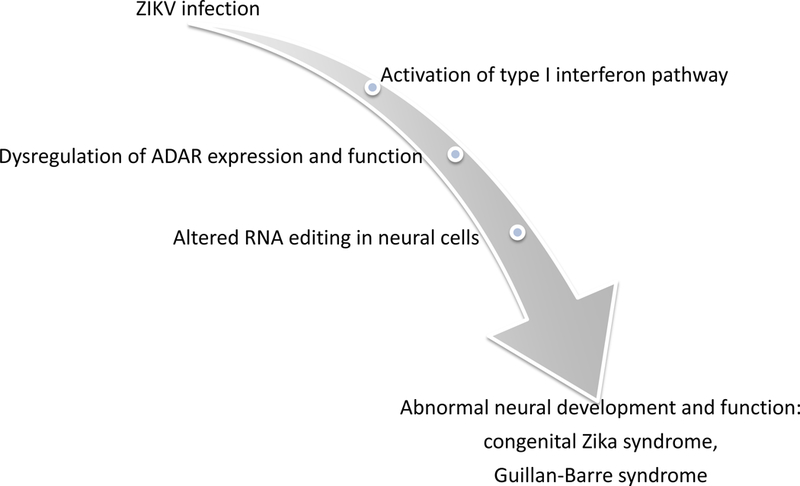

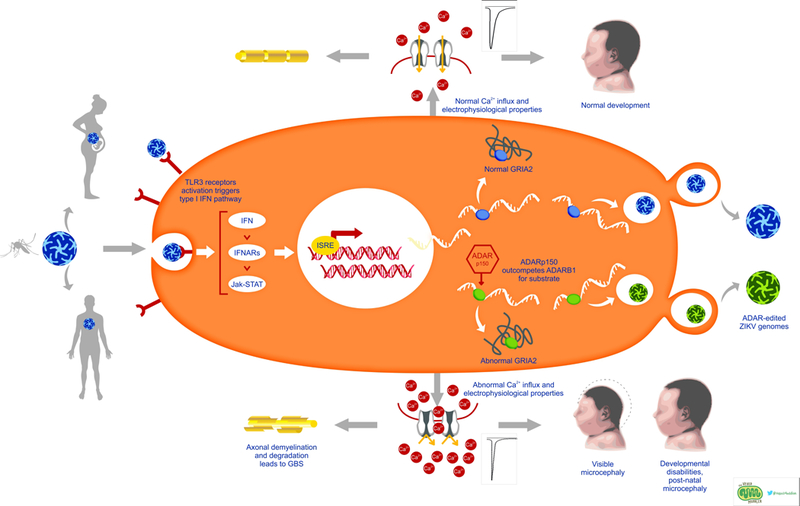

We now build the case that ZIKV-mediated pathogenicity – both fetal and adult - is due to dysregulation of the activity of the RNA-editing enzymes, ADARs (Adenosine Deaminases Acting on RNA), which in turn leads to inappropriate levels of post-transcriptional editing of key proteins involved in metabolism of calcium and other ions, and homeostasis in neural cells, thereby triggering a cascade of diverse neurological effects (Figure 1). We propose that viral-triggered dysregulation of ADAR editing results in altered amino acid changes in key neural proteins involved in ion transport and neurotransmitter metabolism. Either an excess or a paucity of developmentally appropriate edits lead to changes in ion permeability and excitability, ultimately resulting in excitotoxicity and neuronal demise [43] [44]. This host-related mechanism is distinct from other proposed mechanisms in that it appears to be a side effect of the normal innate immune response rather than an abnormal process triggered by viral infection.

Figure 1.

Simplified (A) and detailed (B) summaries of our new hypothesis linking ZIKV infection to congenital Zika syndrome and Guillain-Barre syndrome. (B) Overview of ZIKV infection and the proposed mechanistic model of ZIKV-mediated pathogenesis. Upon infection, ZIKV activates Toll-like-Receptor 3 (TLR3), which in turn activates the interferon (IFN) pathway [118, 119]. Interferon-sensitive response elements upregulate interferon-stimulated genes, including the ADAR p150 isoform [59]. Thus, in addition to ADAR editing of viral RNA as part of cell-autonomous immunity, ZIKV-driven activation of ADARp150 may also lead to dysregulation of ADAR editing within host cells. These changes in levels of ADAR editing may be due to increased abundance of ADAR p150 enzyme copies and/or due to interference between ADAR p150 and other ADARs, e.g., through substrate competition with ADARB1 [57, 101]. In turn, ZIKV-induced changes in editing patterns of host transcripts – such as neurotransmitter receptors and transporters - can result in physiological changes in host proteins, such as changes in ion permeability and excitability as illustrated by GRIA2 and GRIA3 [76, 80], in turn leading to excitotoxicity and neuronal demise [43, 44]. Artistic drawing is by Peggy Muddles, @vexedmuddler.

What Are ADARs?

ADARs (Adenosine Deaminases Acting on RNA) are RNA editing enzymes that deaminate adenosines (A) to produce inosines (I) within double-stranded RNAs [45, 46]. These A-to-I changes are translated as A-to-G substitutions in mRNA transcripts, thereby modulating proteome diversity and expression by introducing nonsynonymous substitutions or splice site changes, and serving as a mechanism of dynamic and nuanced post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression [47] [48]. There are three mammalian ADAR loci - ADAR, ADARB1 and ADARB2 [49]. Only ADAR and ADARB1 have proven deaminase activity [50], while ADARB2 is thought to play a regulatory role through competition with other ADARs for substrate [46, 51]. It should be noted that expression and editing activities of one family member can be influenced by expression and editing activities of the other ADARs [52] [53]. ADARs play a particularly prominent role in the nervous system as the majority of ADAR editing target genes are expressed in the nervous system, including brain [49]. It has been suggested that ADARs also contribute to functions beyond editing, such as protein-RNA binding or RNA folding [54].

ADAR Expression Is Elevated in ZIKV-infected Cells That Exhibit Cytopathic Effects

McGrath et al. (2017) recently examined the consequences of ZIKV infection in three cell lines of primary human neural stem cells originally derived from three individual fetal brains [55]. Two lines (K048 and K054) exhibited signs of reduced neuronal differentiation (an observation that is consistent with other ZIKV infected brain studies, including in vivo), while such signs were not observed in the third line, G010 [55]. Differential gene expression analysis showed global similarities in transcriptome changes in K048 and K054, which were not shared with G010, particularly among genes involved in innate immune pathways [55]. Their supplementary list of differentially expressed genes reported that ADAR gene expression increased significantly in K048 and K054 in response to ZIKV infection, while remained the same in G010. In other words, only the cell lines with the observable cytopathic effects exhibited an increase in ADAR expression (of course, the relationship between expression and editing may not necessarily be linear [56]). While no significant change in expression of ADARB1 and ADARB2 was reported, it should be noted that changes in the ADAR gene expression can interfere with the specific editing activity of these other ADAR-related enzymes [57, 58].

Our re-analysis of the McGrath et al. (2017) transcriptome data [55] shows that ADAR editing activity per se -- not merely expression of ADAR -- appears to be higher in the cell lines with more prominent cytopathic effects. Using the SnpEff variant annotation tool implemented in GATK, we re-analyzed the transcriptome data of the mock and ZIKV-infected cell lines to quantify the nucleotide sequence variability of their mRNAs on a gene-by-gene basis. We found that the ZIKV-infected samples harbor significantly higher numbers of A-to-G-changes (i.e., changes that can be attributed to ADAR activity) in K048 compared to mock-infected line (Mood’s median test, P = 0.014). Conversely, no such significant differences were observed in K054, where cytopathic effects were not as prominent as in K048, and in G010 (P > 0.05). Comparable results were obtained when the mRNA sequence variability of the transcriptome data was alternatively assessed with the GATK Haplotype Caller (i.e., almost four times more A-to-G changes were found in the ZIKV-infected than mock cell lines, including in the well-known editing target GRIA3). These preliminary findings offer only an initial glimpse into the potential effects of ADAR editing in ZIKV infection. They will require further experimental confirmation, including careful validation of editing changes (if any) of specific key neural genes and/or whether potential differences of normal editing patterns among individuals may be contributing to pathogenesis mechanisms. Nonetheless, these preliminary findings are consistent with the proposed hypothesis about the role of dysregulated editing changes in ZIKV infections by the redirection of ADAR editing activity, specifically, that of the IFN-induced ADARp150 isoform [59], away from the host editome to ZIKV, and/or through changes in normal host editing patterns because of increased ADAR p150 editing activity and/or interference between different ADARs.

Appropriate ADAR Editing Is Required For Proper Neuronal Development

Severe CNS phenotypes are observed in ADAR knockouts and ADAR deficiency or loss of function studies (e.g., [60]), including embryonic lethality [61], epilepsy, motor neuron death [62], microcephaly and neural tube defects [63]. Likewise, decreased ADARB1 editing activity plays a role in the pathogenesis of a common motor neuron disease, sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [64], and various brain and neurological cancers [57, 65].

Mutations and polymorphisms in ADAR loci, such as the ADARB2 polymorphisms, have been implicated in complex neurological phenotypes such as migraines [66], autism [67], and genetic epilepsy [68]. Likewise, mutations in the ADAR gene that affect efficacy of RNA binding and/or A-to-I editing [69] have been associated with a rare human Mendelian disease, Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome [70] [71]. In its typical form, the damage caused this disease resembles neurodevelopmental pathology due to in utero infection [72], and is associated with an increased level of interferon and upregulation of interferon-stimulated genes [73].

ADAR editing is enriched in the nervous system [74]. One prominent example of ADAR editing in the brain is the Q/R site of the glutamate receptor subunit GRIA2 (also known as GluA2), where virtually complete (~100%) editing [75] of glutamine codon 607 (Q607) to arginine (R) results in multiple changes of the receptor properties, including cellular permeability to calcium (Ca2+) [76]. Under-editing of the Q607R GRIA2 site (e.g., in the case of ADARB1 deficiency) results in increased influx of calcium and neuronal death [77]. GRIA2 has an additional editing site, R764G, which is edited mostly by ADAR, and results in different electrophysiological properties. Editing at R764G gradually increases during neural development, and the edited isoform fraction in adult brains ranges from 50% to 85% [78].

Another well-documented ADAR editing event (via ADARB1) results in I-to-M, Q-to-R, and Y-to-C amino acid changes in the mammalian calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 D channel CACNA1D (also known as CaV1.3) within the IQ domain, a calmodulin-binding site responsible for regulating sensitivity to inhibitory Ca2+-feedback (CDI) [79]. Edited CACNA1D proteins are expressed in both brain tissue and the surface membranes of primary neurons; neurons with edited CACNA1D proteins show decreased CDI, as part of likely selective fine-tuning of Ca2+ feedback for low-voltage activated Ca2+ influx [79].

GRIA2 and CACNA1D are not the only ADAR editing targets critical for neural function. Functionally relevant editing targets include other glutamate receptors, such as glutamate receptor subunit GRIA3 (also known as GluA3) [80], receptors for other neurotransmitters, including excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters, such as serotonin 2C receptor 5HT2CR [81] and the alpha3 subunit of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor (Gabra3) [82], respectively, as well as ion channels (e.g., voltage-dependent potassium channel KCNA1 [83]), and microRNAs [84]. Disruption of editing of these targets is known to lead to changes in excitability, kinetics and other crucial functions of these receptors and ion channels, ultimately resulting in neurodevelopmental defects, decreased proliferation and neuronal death [43].

Thus, seemingly minor amino acid changes in these proteins have the potential to significantly alter electrophysiology, calcium permeability and metabolism, among other properties, in neural (and likely glial) cells, thereby initiating a broad array of downstream neurophysiological changes such as those observed in CZS and GBS. Indeed, because of glutamate’s fundamental role as a major excitatory neurotransmitter in as many as 80 to 90% of brain neurons, most neurons and many glial cells have glutamate receptors in their membranes [85]. Glutamatergic signaling also plays a critical role in regulation of neural development, including neurotoxic effects of increased calcium permeability due to, for example, inappropriate editing of GRIA2 [86]. These different examples offer a potential common explanation for the breadth of the observed clinical symptoms and defects in both fetal and adult ZIKV infections, where variation in specific manifestations across developmental stage at the time of infection can be attributed to the nuanced spatio-temporal regulation of ADAR editing – and/or its infection-mediated dysregulation, particularly in neural cells [87].

ADAR is Part of the Antiviral Response

Expression of ADARs, specifically, the ADAR1 p150 isoform, is regulated by interferon as part of cell-autonomous immunity [59]. ADAR editing plays a role in an anti-viral activity, as part of the innate immune response [88]. Recent experimental ZIKV studies have shown that the interferon (IFN) type I response plays a role in ZIKV infection, that is in human ZIKV infections, expression of IFN cytokines increases, followed by increased expression of IFN-regulated genes [55], including ADARs. The interactions between ZIKV and IFN pathway activation are complex, including mechanisms that suppress IFN signaling as part of viral evasion strategy, such as the viral NS5 protein [89], or targeting STAT1 [90] and STAT2 [91]. Differences among ZIKV strains in their ability to antagonize IFN response [89] [90], and/or specific variants of human genes, or a combination of the two may help explain why not all ZIKV-positive pregnancies – or even fetuses from the same pregnancy – show neurodevelopmental defects [92].

Our recent comparative work revealed a distinct ADAR editing signature in viral genomes [93], including ZIKV, suggesting that host ADAR editing plays a role in the molecular evolution of ZIKV[94]. Our findings were corroborated by an independent evolutionary study [95] that used a different approach from ours to identify ADAR editing footprints in ZIKV genomes. Together, these results indicate that ADAR editing is active during ZIKV infection. While it remains to be determined whether observed ADAR editing footprints are due to ADAR action in the mosquito or mammalian host (or both) [94], studies of the mammalian immune response support the hypothesis that ADAR (specifically, the IFN-induced ADARp150 isoform) is activated in ZIKV infections.

Dysregulation of ADAR editing could potentially contribute to ZIKV pathogenesis via decreased host editing (i.e., if ADAR editing activity is re-directed from the host editome to ZIKV) or via increased host editing due to elevated expression of ADAR p150. ADAR p150 might directly alter editing patterns, or do so indirectly if a stoichiometric change between ADAR p150 and other ADARs modifies editing patterns. As noted previously, in mice both ADAR and ADARB1 knockouts can be fatal, e.g., due to under-editing of key transcripts such as GRIA2 [77]. There is mounting evidence that off-target editing by ADAR is also deleterious in humans [96].

Thus, one potential explanation for the mechanisms of CZS may be attributed to the disruption of editing and regulatory function of ADAR genes due to ZIKV-mediated IFN pathway activation (Figure 1). Specifically, the physiological consequences of this ADAR editing dysregulation may be particularly critical for key synaptic signaling proteins, which in turn result in shifts in calcium metabolism and homeostasis in the developing brain. For example, changes in ADAR editing patterns can be linked to changes in (i) calcium permeability, and thus, channel conductivity of GRIA2 and GRIA3 [97], and (ii) changes in how multiple isoforms of 5-HT2C – that have different binding affinities and functional potencies of agonists and that have been linked to mental disorders and suicide [98] – are distributed within the brain. Appropriate ADAR editing thus could influence synaptic transmission, as well as regulation of cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation [99], in proliferative zones of the developing brain [100]. Dysregulation of ADAR activity can also be potentially connected to the neurodegeneration observed in GBS, where IFN-triggered elevated expression of ADAR could result in abnormal editing of proteins involved in synaptic signaling, thereby changing the ion homeostasis of neurons, and hence, triggering the subsequent cascade of effects, similar to what is observed in CZS.

Testing the New Hypothesis

We posit that the available experimental evidence from both the CZS and GBS cases is consistent with the expectations of the hypothesis presented here. However, a causal link between ADAR editing and subsequent neurodevelopmental or neurodegenerative sequelae in CZS or GBS remains to be demonstrated. Importantly, the proposed mechanistic hypothesis lends itself to multiple tests to further explore the role of editing dysregulation in viral pathogenesis. A critical first step will be to comprehensively document differences in ADAR expression and editing levels in ZIKV infection during different stages of pregnancy and fetal development, as well as in GBS, including self-regulation aspects of ADAR loci themselves [101] [53]. These critical tests can be done with standard transcriptome analyses and should concentrate on the expression and activity of calcium homeostasis and metabolism proteins [44]. One way to test the link between ADAR editing dysregulation and viral-induced cellular damage would be to supplement ZIKV infection with inhibitors of ADAR activity and/or activity of its upstream regulator, IFN, in cell culture or brain organoids [102]. The expectation is that in the absence of abnormal ADAR activation there would be minimal, if any, viral-mediated damage to the cells. This is consistent with recent observations that ZIKV infection of embryonic stem cells results in very little damage despite demonstrated infectivity [29], unlike the major cytopathic effects observed in infection of neural progenitor cells. This can be attributed in part to the lack of the innate immune response in embryonic stem cells [103], including underdeveloped IFN pathways and the absence of viral RNA receptors [104].

Likewise, the functional consequences of dysregulated ADAR editing, particularly signs of calcium excitotoxicity [44], should be contrasted between cell lines infected with ZIKV and mock-infected controls, where IFN activation leading to changes in ADAR editing is stimulated by poly I:C (polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid, a synthetic viral mimetic that activates Toll-like-Receptor 3), or similar compounds [105]. It is important to consider both the long-term consequences of IFN/ADAR activation on cell/organoid growth, and whether editing or any cytopathic effects exhibit dose-dependent relationships. Other factors to consider for future testing are the interactions between the developmental stage and/or tissue type of infected cells and the baseline ADAR editing level, as well as the presence/absence of potential ADAR editing targets. For example, one can evaluate whether ocular damage [106] is associated with dysregulation of developmentally important ADAR editing of GABA type A receptor subunit a3 in the retina [107], among other ADAR targets. Comparisons of the distribution and expression of edited and unedited isoforms at both the transcript and protein levels will be critical in such experiments.

Furthermore, future testing should focus on the patterns and regulatory processes involved in nuanced spatio-temporal changes in ADAR editing in brain development during normal as well as ZIKV-positive pregnancies, and how these changes are linked to observed clinical symptoms. The observation of differential editing activity and its ramp-up during brain development [108] [109] must be supplemented by a deeper understanding of how editing is regulated during different stages of brain development and/or different locations in the CNS. In addition to protein-coding targets of ADAR editing, changes in editing of other molecular targets should also be explored, including microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs [110] [111]. This can be greatly aided by recently developed precision approaches such as single-cell transcriptomics [112] and brain organoids, which can closely recapitulate human brain development [113] [102]. Non-invasive pre-natal testing of viral-triggered changes in ADAR expression and/or editing biomarkers can be developed using intact fetal cells derived from the maternal blood [114].

Other Future Research Prospects

Our mechanistic explanation suggests potential treatment strategies for intervention in the dysregulation of ADAR editing during or shortly after ZIKV infection with the aim of preventing or diminishing the spectrum of ZIKV pathogenic/neurodevelopmental sequelae. For example, during pregnancy, within two-three weeks of diagnosed ZIKV infection [115], a short course of drugs leading to the suppression of the type I interferon pathway would be expected to result in down-regulation of fetal ADAR activity. This could be achieved by administering treatments currently used, e.g., to treat lupus [116]. Although such treatments will be complicated by the fact that not all pregnant women exhibit clinical signs of ZIKV infection [9], the timing of asymptomatic infections can be inferred if there is a finite window of exposure. This approach can potentially be augmented by development of biomarkers that reflect ADAR activity and/or editing levels [117]. Likewise, a similar course of treatment can be applied if early GBS symptoms were to appear a few weeks post-ZIKV infection (similar to that in HCV infections [118]). Further, the role of the type III IFN pathway, including its recently discovered member, IFN-lambda4 [119] [120], in the regulation of immune response, including interactions with the type I IFNs, needs to be considered too [121] [32]. Additionally, development of treatments specifically aimed at the reversal of deleterious editing effects can also be pursued, e.g., via a combination of short-term stimulation of expression of ADAR editing targets, administration of antagonists to the edited protein versions and/or temporary suppression of ADAR editing. Replacement-focused therapies similar to those of paralysis treatment via stimulation of neural growth [122] or directed editing could prove promising too [123] [124].

The same molecular mechanism postulated here to explain ZIKV pathogenesis may underlie other conditions. For example, the increased editing of the calcium channel CaV1.3 has been observed in dopamine-containing neurons affected in Parkinson’s disease, the second most frequent neurodegenerative disease in the world [125]. Currently we have neither a cure for Parkinson’s disease nor a firm understanding of its underlying mechanisms [126], although it appears that (some form of) calcium dysregulation likely plays a prominent role [127]. Evidence suggests that even in the early stages of Parkinson’s disease the calcium homeostasis is disturbed, in part attributable to what appears to be a shift in the cells reliance on (editable) CaV1.3 in lieu of CaV1.2 [128]. Although it remains unclear whether the changes in channel kinetics are due to CaV1.3 editing, and/or differential expression of alternatively spliced isoforms of CaV1.3 [129], this scenario offers an explanation of yet another neurodegenerative condition (in addition to GBS) with unclear aetiology that could potentially be linked to possible changes in ADAR editing patterns induced by prior infections (e.g., [130]), likely of minor viral variety, which have mild to subclinical symptoms that nonetheless have the potential to (over)activate ADARs as part of cell-autonomous immunity. Could changes in edited calcium channels also explain the brain calcification observed following prenatal cytomegalovirus (a herpesvirus) infection [131] [132]? Interestingly, brain calcification is also a common finding in CZS infants, born with or without microcephaly [133], again suggesting a role for ADAR editing in ZIKV pathogenesis. Given these possibilities, we would like to call for systematic, concerted and broad efforts to understand the nuances of spatio-temporal distribution of ADARs and associated editing activity throughout the brain and primary neurons, both in pregnancy and postnatally, as well as the influence of viral infections (including ZIKV) on such activity and subsequent clinical consequences.

Conclusions and Outlook

The paradox of ZIKV-mediated pathogenesis - where mostly benign and asymptomatic infection in adults significantly increases the risks of pregnancy loss and severe neurodevelopmental defects - continues to stump the scientific community. Despite major advances over the last several years towards understanding multiple aspects of ZIKV biology and ZIKV-associated pathogenesis, including the role of viral diversity and a variety of host-related processes, it remains unknown how ZIKV causes fetal and neonatal complications or how it contributes to severe (even if rare) neurotoxic symptoms in adults. The proposed hypothesis of ADAR editing dysregulation triggered by ZIKV infection offers a new way to think about ZIKV pathogenesis and potentially other viral infections. Unlike many other explanations, this novel hypothesis offers a shared mechanistic explanation for a broad range of observed ZIKV sequelae across human life span, from fetal demise to gross fetal defects to subtle hearing defects and learning disabilities, to adult neurodegeneration. Notably, the proposed mechanism is unlikely to be unique to ZIKV, thereby enabling us to better understand the consequences of other viral infections, including the need to better identify fetal and neurotoxic sequelae of viruses often co-circulating with ZIKV, such as West Nile virus and CHIKV [134] [135] [35]. Although many aspects of ADAR editing dysregulation in ZIKV infection remain to be elucidated, including the broader role of IFN pathways, this potential mechanistic insight enables us to address a wide range of observed defects and symptoms in a unified fashion, and to focus on new strategies of prevention, detection and treatment that can be applied across different life stages.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. W.F. Martin for encouragement, and Dr. Andrew Moore and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments that helped improve this manuscript. This work was partially supported by a Kent State University Research Council Seed Award, and Brain Health Institute Pilot Award to HP. MLW was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant number GM083192.

Abbreviations:

- ADAR

Adenosine Deaminases Acting on RNA

- CDI

inhibitory Ca2+-feedback

- CHIKV

chikungunya virus

- CZS

congenital Zika syndrome

- DENV

dengue virus

- GBS

Guillain-Barre syndrome

- IFN

interferon

- ZIKV

Zika virus

References used

- [1].Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Petersen LR, N Engl J Med 2016, 374, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Vannice KS, Cassetti MC, Eisinger RW, Hombach J, Knezevic I, Marston HD, Wilder-Smith A, Cavaleri M, Krause PR, Vaccine 2019, 37, 863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].GBD 2016 DALYs and HALE Collaborators, Lancet 2017, 390, 1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cao-Lormeau VM, Blake A, Mons S, Lastere S, Roche C, Vanhomwegen J, Dub T, Baudouin L, Teissier A, Larre P, Vial AL, Decam C, Choumet V, Halstead SK, Willison HJ, Musset L, Manuguerra JC, Despres P, Fournier E, Mallet HP, Musso D, Fontanet A, Neil J, Ghawche F, Lancet 2016, 387, 1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].van den Berg B, Walgaard C, Drenthen J, Fokke C, Jacobs BC, van Doorn PA, Nat Rev Neurol 2014, 10, 469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Landry MD, Raman SR, Kennedy K, Bettger JP, Magnusson D, Phys Ther 2017, 97, 275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, Powers AM, Kool JL, Lanciotti RS, Pretrick M, Marfel M, Holzbauer S, Dubray C, Guillaumot L, Griggs A, Bel M, Lambert AJ, Laven J, Kosoy O, Panella A, Biggerstaff BJ, Fischer M, Hayes EB, N Engl J Med 2009, 360, 2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Li J, Chong CY, Tan NW, Yung CF, Tee NW, Thoon KC, Clin Infect Dis 2017, 64, 1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Honein MA, Dawson AL, Petersen EE, Jones AM, Lee EH, Yazdy MM, Ahmad N, Macdonald J, Evert N, Bingham A, JAMA 2017, 317, 59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Reynolds MR, Jones AM, Petersen EE, Lee EH, Rice ME, Bingham A, Ellington SR, Evert N, Reagan-Steiner S, Oduyebo T, Brown CM, Martin S, Ahmad N, Bhatnagar J, Macdonald J, Gould C, Fine AD, Polen KD, Lake-Burger H, Hillard CL, Hall N, Yazdy MM, Slaughter K, Sommer JN, Adamski A, Raycraft M, Fleck-Derderian S, Gupta J, Newsome K, Baez-Santiago M, Slavinski S, White JL, Moore CA, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Petersen L, Boyle C, Jamieson DJ, Meaney-Delman D, Honein MA, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017, 66, 366.28384133 [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hoen B, Schaub B, Funk AL, Ardillon V, Boullard M, Cabie A, Callier C, Carles G, Cassadou S, Cesaire R, Douine M, Herrmann-Storck C, Kadhel P, Laouenan C, Madec Y, Monthieux A, Nacher M, Najioullah F, Rousset D, Ryan C, Schepers K, Stegmann-Planchard S, Tressieres B, Volumenie JL, Yassinguezo S, Janky E, Fontanet A, N Engl J Med 2018, 378, 985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Adams Waldorf KM, Nelson BR, Stencel-Baerenwald JE, Studholme C, Kapur RP, Armistead B, Walker CL, Merillat S, Vornhagen J, Tisoncik-Go J, Baldessari A, Coleman M, Dighe MK, Shaw DWW, Roby JA, Santana-Ufret V, Boldenow E, Li J, Gao X, Davis MA, Swanstrom JA, Jensen K, Widman DG, Baric RS, Medwid JT, Hanley KA, Ogle J, Gough GM, Lee W, English C, Durning WM, Thiel J, Gatenby C, Dewey EC, Fairgrieve MR, Hodge RD, Grant RF, Kuller L, Dobyns WB, Hevner RF, Gale M Jr., Rajagopal L, Nat Med 2018, 24, 368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].de Oliveira Dias JR, Ventura CV, de Paula Freitas B, Prazeres J, Ventura LO, Bravo-Filho V, Aleman T, Ko AI, Zin A, Belfort R, Maia M, Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 2018, pii: S1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Leal MC, Muniz LF, Ferreira TS, Santos CM, Almeida LC, Van Der Linden V, Ramos RC, Rodrigues LC, Neto SS, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016, 65, 917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hotez PJ, JAMA Pediatr 2016, 170, 787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Oliveira-Filho J, Felzemburgh R, Costa F, Nery N, Mattos A, Henriques DF, Ko AI, For T The Salvador Zika Response, Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018, 98, 1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Willison HJ, Jacobs BC, van Doorn PA, Lancet 2016, 388, 717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].van Leeuwen N, Lingsma HF, Vanrolleghem AM, Sturkenboom MC, van Doorn PA, Steyerberg EW, Jacobs BC, PLoS One 2016, 11, e0143837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Medina MT, Medina-Montoya M, J Neurol Sci 2017, 383, 214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Liu ZY, Shi WF, Qin CF, Nat Rev Microbiol 2019, 17, 131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pettersson JH-O, Eldholm V, Seligman SJ, Lundkvist Å, Falconar AK, Gaunt MW, Musso D, Nougairède A, Charrel R, Gould EA, de Lamballerie X, MBio 2016, 7, e01239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yuan L, Huang XY, Liu ZY, Zhang F, Zhu XL, Yu JY, Ji X, Xu YP, Li G, Li C, Wang HJ, Deng YQ, Wu M, Cheng ML, Ye Q, Xie DY, Li XF, Wang X, Shi W, Hu B, Shi PY, Xu Z, Qin CF, Science 2017, 358, 933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Alpuche-Lazcano SP, McCullogh CR, Del Corpo O, Rance E, Scarborough RJ, Mouland AJ, Sagan SM, Teixeira MM, Gatignol A, Viruses 2018, 10, pii: E53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Barnard TR, Rajah MM, Sagan SM, Viruses 2018, 10, pii: E728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Annamalai AS, Pattnaik A, Sahoo BR, Muthukrishnan E, Natarajan SK, Steffen D, Vu HLX, Delhon G, Osorio FA, Petro TM, Xiang SH, Pattnaik AK, J Virol 2017, pii: JVI.01348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chavali PL, Stojic L, Meredith LW, Joseph N, Nahorski MS, Sanford TJ, Sweeney TR, Krishna BA, Hosmillo M, Firth AE, Bayliss R, Marcelis CL, Lindsay S, Goodfellow I, Woods CG, Gergely F, Science 2017, 357, 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Pierson TC, Diamond MS, Nature 2018, 560, 573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li H, Saucedo-Cuevas L, Yuan L, Ross D, Johansen A, Sands D, Stanley V, Guemez-Gamboa A, Gregor A, Evans T, Chen S, Tan L, Molina H, Sheets N, Shiryaev SA, Terskikh AV, Gladfelter AS, Shresta S, Xu Z, Gleeson JG, Neuron 2019, pii: S0896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tang H, Hammack C, Ogden SC, Wen Z, Qian X, Li Y, Yao B, Shin J, Zhang F, Lee EM, Christian KM, Didier RA, Jin P, Song H, Ming GL, Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Garcez PP, Loiola EC, Madeiro da Costa R, Higa LM, Trindade P, Delvecchio R, Nascimento JM, Brindeiro R, Tanuri A, Rehen SK, Science 2016, 352, 816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chiramel AI, Best SM, Virus Res 2017, 254, 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pardy RD, Valbon SF, Richer MJ, Cytokine 2019, 119, 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Acosta-Ampudia Y, Monsalve DM, Castillo-Medina LF, Rodriguez Y, Pacheco Y, Halstead S, Willison HJ, Anaya JM, Ramirez-Santana C, Front Mol Neurosci 2018, 11, 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lucchese G, Kanduc D, Autoimmun Rev 2016, 15, 801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Platt DJ, Smith AM, Arora N, Diamond MS, Coyne CB, Miner JJ, Sci Transl Med 2018, 10, pii: eaao7090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yockey LJ, Iwasaki A, Immunity 2018, 49, 397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Trus I, Darbellay J, Huang Y, Gilmour M, Safronetz D, Gerdts V, Karniychuk U, Virulence 2018, 9, 1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Vogels CBF, Ruckert C, Cavany SM, Perkins TA, Ebel GD, Grubaugh ND, PLoS Biol 2019, 17, e3000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Andrade DV, Harris E, Virus Res 2017, 254, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dejnirattisai W, Supasa P, Wongwiwat W, Rouvinski A, Barba-Spaeth G, Duangchinda T, Sakuntabhai A, Cao-Lormeau VM, Malasit P, Rey FA, Mongkolsapaya J, Screaton GR, Nat Immunol 2016, 17, 1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zimmerman MG, Quicke KM, O’Neal JT, Arora N, Machiah D, Priyamvada L, Kauffman RC, Register E, Adekunle O, Swieboda D, Johnson EL, Cordes S, Haddad L, Chakraborty R, Coyne CB, Wrammert J, Suthar MS, Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Brady OJ, Osgood-Zimmerman A, Kassebaum NJ, Ray SE, de Araujo VEM, da Nobrega AA, Frutuoso LCV, Lecca RCR, Stevens A, de Oliveira Zoca B., de Lima JM Jr., Bogoch II, Mayaud P, Jaenisch T, Mokdad AH, Murray CJL, Hay SI, Reiner RC Jr., Marinho F, PLoS Med 2019, 16, e1002755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Gaisler-Salomon I, Kravitz E, Feiler Y, Safran M, Biegon A, Amariglio N, Rechavi G, Neurobiol Aging 2014, 35, 1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Rosenthal JJ, Seeburg PH, Neuron 2012, 74, 432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Bass BL, Annu Rev Biochem 2002, 71, 817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Samuel CE, J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Walkley CR, Liddicoat B, Hartner JC, Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2012, 353, 197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Deffit SN, Hundley HA, Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2016, 7, 113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Li JB, Church GM, Nat Neurosci 2013, 16, 1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Walkley CR, Liddicoat B, Hartner JC, in Adenosine Deaminases Acting on RNA (ADARs) and A-to-I Editing, (Ed: Samuel CE), Springer, 2011, 197. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Savva YA, Rieder LE, Reenan RA, Genome Biol 2012, 13, 252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Gallo A, Vukic D, Michalik D, O’Connell MA, Keegan LP, Hum Genet 2017, 136, 1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Tan BZ, Huang H, Lam R, Soong TW, Mol Brain 2009, 2, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Licht K, Jantsch MF, Bioessays 2017, 39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].McGrath EL, Rossi SL, Gao J, Widen SG, Grant AC, Dunn TJ, Azar SR, Roundy CM, Xiong Y, Prusak DJ, Loucas BD, Wood TG, Yu Y, Fernandez-Salas I, Weaver SC, Vasilakis N, Wu P, Stem Cell Reports 2017, 8, 715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Garncarz W, Tariq A, Handl C, Pusch O, Jantsch MF, RNA Biol 2013, 10, 192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Cenci C, Barzotti R, Galeano F, Corbelli S, Rota R, Massimi L, Di Rocco C, O’Connell MA, Gallo A, J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 7251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Jacobs MM, Fogg RL, Emeson RB, Stanwood GD, Dev Neurosci 2009, 31, 223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].MacMicking JD, Nat Rev Immunol 2012, 12, 367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Riedmann EM, Schopoff S, Hartner JC, Jantsch MF, RNA 2008, 14, 1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Wang Q, Khillan J, Gadue P, Nishikura K, Science 2000, 290, 1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Yamashita T, Tadami C, Nishimoto Y, Hideyama T, Kimura D, Suzuki T, Kwak S, Neurosci Res 2012, 73, 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Lanzi G, Fazzi E, D’Arrigo S, Orcesi S, Maraucci I, Uggetti C, Bertini E, Lebon P, Neurology 2005, 64, 1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kwak S, Hideyama T, Yamashita T, Aizawa H, Neuropathology 2010, 30, 182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Galeano F, Leroy A, Rossetti C, Gromova I, Gautier P, Keegan LP, Massimi L, Di Rocco C, O’Connell MA, Gallo A, Int J Cancer 2010, 127, 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Cox HC, Lea RA, Bellis C, Carless M, Dyer TD, Curran J, Charlesworth J, Macgregor S, Nyholt D, Chasman D, Neurogenetics 2012, 13, 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Ben-David E, Granot-Hershkovitz E, Monderer-Rothkoff G, Lerer E, Levi S, Yaari M, Ebstein RP, Yirmiya N, Shifman S, Hum Mol Genet 2011, 20, 3632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Mittaz L, Antonarakis SE, Higuchi M, Scott HS, Hum Genet 1997, 100, 398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Fisher AJ, Beal PA, RNA Biol 2017, 14, 164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Crow YJ, Manel N, Nat Rev Immunol 2015, 15, 429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Goutieres F, Aicardi J, Barth PG, Lebon P, Ann Neurol 1998, 44, 900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Rice GI, Kasher PR, Forte GM, Mannion NM, Greenwood SM, Szynkiewicz M, Dickerson JE, Bhaskar SS, Zampini M, Briggs TA, Jenkinson EM, Bacino CA, Battini R, Bertini E, Brogan PA, Brueton LA, Carpanelli M, De Laet C, de Lonlay P, del Toro M, Desguerre I, Fazzi E, Garcia-Cazorla A, Heiberg A, Kawaguchi M, Kumar R, Lin JP, Lourenco CM, Male AM, Marques W Jr., Mignot C, Olivieri I, Orcesi S, Prabhakar P, Rasmussen M, Robinson RA, Rozenberg F, Schmidt JL, Steindl K, Tan TY, van der Merwe WG, Vanderver A, Vassallo G, Wakeling EL, Wassmer E, Whittaker E, Livingston JH, Lebon P, Suzuki T, McLaughlin PJ, Keegan LP, O’Connell MA, Lovell SC, Crow YJ, Nat Genet 2012, 44, 1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Livingston JH, Crow YJ, Neuropediatrics 2016, 47, 355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Levanon EY, Hallegger M, Kinar Y, Shemesh R, Djinovic-Carugo K, Rechavi G, Jantsch MF, Eisenberg E, Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33, 1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Kawahara Y, Ito K, Sun H, Aizawa H, Kanazawa I, Kwak S, Nature 2004, 427, 801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Hideyama T, Yamashita T, Aizawa H, Tsuji S, Kakita A, Takahashi H, Kwak S, Neurobiol Dis 2012, 45, 1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Tariq A, Jantsch MF, Front Neurosci 2012, 6, 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Pachernegg S, Munster Y, Muth-Kohne E, Fuhrmann G, Hollmann M, Front Cell Neurosci 2015, 9, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Huang H, Tan BZ, Shen Y, Tao J, Jiang F, Sung YY, Ng CK, Raida M, Kohr G, Higuchi M, Fatemi-Shariatpanahi H, Harden B, Yue DT, Soong TW, Neuron 2012, 73, 304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Bonini D, Filippini A, La Via L, Fiorentini C, Fumagalli F, Colombi M, Barbon A, RNA Biol 2015, 12, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Werry TD, Loiacono R, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A, Pharmacol Ther 2008, 119, 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Rula EY, Lagrange AH, Jacobs MM, Hu N, Macdonald RL, Emeson RB, J Neurosci 2008, 28, 6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Holmgren M, Rosenthal JJ, Curr Issues Mol Biol 2015, 17, 23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Nishikura K, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016, 17, 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Danbolt NC, Furness DN, Zhou Y, Neurochem Int 2016, 98, 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Seeburg PH, Higuchi M, Sprengel R, Brain Res Brain Res Rev 1998, 26, 217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Huntley MA, Lou M, Goldstein LD, Lawrence M, Dijkgraaf GJ, Kaminker JS, Gentleman R, BMC Genomics 2016, 17, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Samuel CE, Virology 2011, 411, 180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Grant A, Ponia SS, Tripathi S, Balasubramaniam V, Miorin L, Sourisseau M, Schwarz MC, Sanchez-Seco MP, Evans MJ, Best SM, Garcia-Sastre A, Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Bowen JR, Quicke KM, Maddur MS, O’Neal JT, McDonald CE, Fedorova NB, Puri V, Shabman RS, Pulendran B, Suthar MS, PLoS Pathog 2017, 13, e1006164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Tripathi S, Balasubramaniam VR, Brown JA, Mena I, Grant A, Bardina SV, Maringer K, Schwarz MC, Maestre AM, Sourisseau M, Albrecht RA, Krammer F, Evans MJ, Fernandez-Sesma A, Lim JK, Garcia-Sastre A, PLoS Pathog 2017, 13, e1006258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Linden VV, Linden HVJ, Leal MC, Rolim ELF, Linden AV, Aragao M, Brainer-Lima AM, Cruz D, Ventura LO, Florencio TLT, Cordeiro MT, Caudas SDSN, Ramos RC, Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2017, 75, 381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Piontkivska H, Matos LF, Paul S, Scharfenberg B, Farmerie WG, Miyamoto MM, Wayne ML, Genome Biol Evol 2016, 8, 2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Piontkivska H, Frederick M, Miyamoto MM, Wayne ML, Ecol Evol 2017, 7, 4475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Khrustalev VV, Khrustaleva TA, Sharma N, Giri R, Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Xu GX, Zhang JZ, P Natl Acad Sci USA 2014, 111, 3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Sailer A, Swanson GT, Perez-Otano I, O’Leary L, Malkmus SA, Dyck RH, Dickinson-Anson H, Schiffer HH, Maron C, Yaksh TL, Gage FH, O’Gorman S, Heinemann SF, J Neurosci 1999, 19, 8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Hensler JG, in Basic Neurochemistry. Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects., (Ed: Scott Brady G. S., Wayne Albers R, Price Donald), Elsevier, 2012, 300. [Google Scholar]

- [99].Tohda M, Nomura M, Nomura Y, J Pharmacol Sci 2006, 100, 427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].De Lucchini S, Ori M, Nardini M, Marracci S, Nardi I, Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2003, 115, 196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Oakes E, Anderson A, Cohen-Gadol A, Hundley HA, J Biol Chem 2017, 292, 4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Di Lullo E, Kriegstein AR, Nat Rev Neurosci 2017, 18, 573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].D’Angelo W, Gurung C, Acharya D, Chen B, Ortolano N, Gama V, Bai F, Guo YL, J Immunol 2017, 198, 2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Wang R, Wang J, Paul AM, Acharya D, Bai F, Huang F, Guo YL, J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 15926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Uchida S, Yoshinaga N, Yanagihara K, Yuba E, Kataoka K, Itaka K, Biomaterials 2018, 150, 162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Manangeeswaran M, Kielczewski JL, Sen HN, Xu BC, Ireland DDC, McWilliams IL, Chan CC, Caspi RR, Verthelyi D, Emerg Microbes Infect 2018, 7, 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Ring H, Boije H, Daniel C, Ohlson J, Ohman M, Hallbook F, Vis Neurosci 2010, 27, 149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Wahlstedt H, Daniel C, Enstero M, Ohman M, Genome Res 2009, 19, 978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Hwang T, Park CK, Leung AK, Gao Y, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, Rajpurohit A, Tao R, Shin JH, Weinberger DR, Nat Neurosci 2016, 19, 1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Slezak-Prochazka I, Durmus S, Kroesen BJ, van den Berg A, RNA 2010, 16, 1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Nigita G, Veneziano D, Ferro A, Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2015, 3, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Picardi E, Horner DS, Pesole G, RNA 2017, 23, 860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Lancaster MA, Renner M, Martin CA, Wenzel D, Bicknell LS, Hurles ME, Homfray T, Penninger JM, Jackson AP, Knoblich JA, Nature 2013, 501, 373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Wou K, Feinberg JL, Wapner RJ, Simpson JL, Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2015, 15, 989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Majumder MS, Hess R, Ross R, Piontkivska H, F1000Res 2018, 7, 159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Furie R, Khamashta M, Merrill JT, Werth VP, Kalunian K, Brohawn P, Illei GG, Drappa J, Wang L, Yoo S, Arthritis Rheumatol 2017, 69, 376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].van der Laan S, Salvetat N, Weissmann D, Molina F, Drug Discov Today 2017, 22, 1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Doncel-Perez E, Mateos-Hernandez L, Pareja E, Garcia-Forcada A, Villar M, Tobes R, Romero Ganuza F., Del Sol Vila V., Ramos R, Fernandez de Mera IG, de la Fuente J, J Immunol 2016, 196, 1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].O’Brien TR, Prokunina-Olsson L, Donnelly RP, J Interferon Cytokine Res 2014, 34, 829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Obajemu AA, Rao N, Dilley KA, Vargas JM, Sheikh F, Donnelly RP, Shabman RS, Meissner EG, Prokunina-Olsson L, Onabajo OO, J Immunol 2017, 199, 3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Corry J, Arora N, Good CA, Sadovsky Y, Coyne CB, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 9433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Marchesan S, Ballerini L, Prato M, Science 2017, 356, 1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Merkle T, Merz S, Reautschnig P, Blaha A, Li Q, Vogel P, Wettengel J, Li JB, Stafforst T, Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37, 133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Katrekar D, Chen G, Meluzzi D, Ganesh A, Worlikar A, Shih YR, Varghese S, Mali P, Nat Methods 2019, 16, 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].de Lau LM, Breteler MM, Lancet Neurol 2006, 5, 525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Fahn S, Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018, 46 Suppl 1, S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Knorle R, Neurotox Res 2018, 33, 515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Hurley MJ, Brandon B, Gentleman SM, Dexter DT, Brain 2013, 136, 2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Bock G, Gebhart M, Scharinger A, Jangsangthong W, Busquet P, Poggiani C, Sartori S, Mangoni ME, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Herzig S, Striessnig J, Koschak A, J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 42736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Cucca A, Migdadi HA, Di Rocco A, Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018, 46 Suppl 1, S83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Fink KR, Thapa MM, Ishak GE, Pruthi S, Radiographics 2010, 30, 1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Gabrielli L, Bonasoni MP, Lazzarotto T, Lega S, Santini D, Foschini MP, Guerra B, Baccolini F, Piccirilli G, Chiereghin A, Petrisli E, Gardini G, Lanari M, Landini MP, J Clin Virol 2009, 46 Suppl 4, S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].van der Linden V, Pessoa A, Dobyns W, Barkovich AJ, Junior HV, Filho EL, Ribeiro EM, Leal MC, Coimbra PP, Aragao MF, Vercosa I, Ventura C, Ramos RC, Cruz DD, Cordeiro MT, Mota VM, Dott M, Hillard C, Moore CA, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016, 65, 1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Prata-Barbosa A, Cleto-Yamane TL, Robaina JR, Guastavino AB, de Magalhaes-Barbosa MC, Brindeiro RM, Medronho RA, da Cunha A, Int J Infect Dis 2018, 72, 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Mercado-Reyes M, Acosta-Reyes J, Navarro-Lechuga E, Corchuelo S, Rico A, Parra E, Tolosa N, Pardo L, Gonzalez M, Martin-Rodriguez-Hernandez J, Karime-Osorio L, Ospina-Martinez M, Rodriguez-Perea H, Del Rio-Pertuz G, Viasus D, Epidemiol Infect 2019, 147, e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]