Abstract

Background

Training future physicians to provide compassionate, equitable, person-centered care remains a challenge for medical educators. Dialogues offer an opportunity to extend person-centered education into clinical care. In contrast to discussions, dialogues encourage the sharing of authority, expertise, and perspectives to promote new ways of understanding oneself and the world. The best methods for implementing dialogic teaching in graduate medical education have not been identified.

Objective

We developed and implemented a co-constructed faculty development program to promote dialogic teaching and learning in graduate medical education.

Methods

Beginning in April 2017, we co-constructed, with a pilot working group (PWG) of physician teachers, ways to prepare for and implement dialogic teaching in clinical settings. We kept detailed implementation notes and interviewed PWG members. Data were iteratively co-analyzed using a qualitative description approach within a constructivist paradigm. Ongoing analysis informed iterative changes to the faculty development program and dialogic education model. Patient and learner advisers provided practical guidance.

Results

The concepts and practice of dialogic teaching resonated with PWG members. However, they indicated that dialogic teaching was easier to learn about than to implement, citing insufficient time, lack of space, and other structural issues as barriers. Patient and learner advisers provided insights that deepened design, implementation, and eventual evaluation of the education model by sharing experiences related to person-centered care.

Conclusions

While PWG members found that the faculty development program supported the implementation of dialogic teaching, successfully enabling this approach requires expertise, willingness, and support to teach knowledge and skills not traditionally included in medical curricula.

What was known and gap

Dialogic teaching can enhance person-centered education, but methods for implementing the teaching method into graduate medical education have not been identified.

What is new

A co-constructed faculty development program intended to promote dialogic teaching and learning in graduate medical education.

Limitations

The program was implemented at a single institution, limiting generalizability, and participants were self-selected.

Bottom line

Participants found the program and teaching method useful, but successful implementation requires expertise and willingness to learn skills not traditionally included in medical curricula.

Introduction

Teaching physicians to deliver compassionate, person-centered care lies at the heart of humanistic medical education, where technical excellence is matched with recognition and validation of patients' perspectives and a commitment to addressing physicians' societal responsibilities. Kumagai and colleagues1 have proposed this can be done through dialogues, which differ in important ways from discussions (the standard mode of small group teaching).2 Discussions are primarily cognitive and oriented toward finding solutions. Discussions emphasize objectivity and preserve the authority of teachers. In contrast, dialogues are experiential and affective, promoting new ways of understanding oneself and the world, new possibilities, and new questions.2 Dialogues focus on the subjective and encourage the sharing of authority, expertise, and perspectives between traditional teachers and learners.2 Such interactions promote reflection and reflexivity3 by creating space for learners to see the other as an equal relational partner and to question assumptions, power dynamics, and structural inequities in medicine and in society more broadly. Dialogues require trust, respect, and acknowledgment of the power inherent in all interactions.

Citing Woolf,4 Wear and colleagues5 described dialogues as occurring at “moments of being [. . .] encountered in the presence of suffering and healing, death, and dying—that seem to focus one's perspective in a permanent way.” Dialogues are ideally prompted by encounters in the clinical environment, and held parallel to discussions of clinical cases, in order to avoid abstraction and maintain professional and personal relevance.1 However, they can also be centered on “first-person narratives or other stories.”6 Kumagai and Lypson6 described using dialogues to enable the development of a humanistic, social justice orientation by promoting critical consciousness.7 This work brings into medical education nearly a century of social theory.8–11

Dialogic education requires learners and teachers to bring their entire selves into a nonhierarchical conversation about human and social aspects of care.1 This approach incorporates patient experiences to deepen or transform learners' perspectives and values by stimulating critical reflection3 about (1) personal and social identities and ways of knowing that patients, families, and providers bring to interactions, and (2) how the effects of the structures and processes organizing the delivery of care affect those interactions. Dialogic teaching requires medical educators to depart from traditional top-down, expert-novice educational approaches1 that can impede the teaching of core values, such as shared decision-making, relationship building, and compassionate care.

In an effort to educate physicians capable of providing compassionate, equitable, and person-centered care, the Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto recently launched a major initiative in person-centered care that incorporates humanistic values, social justice, and reflective dialogues into its educational programs. The first 2 elements of Person-Centred Care Education are research-informed initiatives that teach (1) non-biomedical aspects of medical care (eg, power, culture, justice, privilege, and equity)12 and their impact on health disparities, and (2) culturally safe practices for the health care of marginalized populations,13 which draw on ideas originally developed by Maori educators to teach trainees to recognize and mitigate inescapable patient-provider power dynamics.14,15 The project described in this article built on these curricula by creating a faculty development program to enable and promote dialogic teaching within our department, including dedicated teaching sessions and a toolkit of resources for faculty to use to prompt dialogues about patient experiences, equity and social responsibility, and person-centered care. As part of this faculty development program, we iteratively developed and implemented a model for dialogic teaching to extend person-centered care education into real-time, situated contexts of clinical care.

Methods

Study Setting

The Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto includes 800 faculty and 1000 postgraduate trainees working at 16 academic and community teaching hospitals in a multicultural metropolitan region of 6 million. Faculty are also responsible for providing core training in internal medicine, emergency medicine, and dermatology to 267 third-year medical students.

Pilot Working Group

Beginning in April 2017, our core project team (including 3 physicians with expertise in dialogic teaching: A.K., A.K.K., L.R.) and a pilot working group (PWG) of physician teachers worked together during 3 meetings to co-construct ways to prepare for and implement dialogic teaching in clinical settings. This collaborative process focused on determining how to teach faculty about dialogic teaching and learning, how to support faculty in concretely implementing it in their own practice, and how to engage further faculty. The PWG consisted of 7 physician teachers (ranging from new faculty to full professors) from different divisions who were experienced in teaching in various clinical settings (general internal medicine, critical care medicine, endocrinology, and rheumatology), in reflective practice, and in faculty development. Initial PWG members were recruited using the core project team's professional networks.

At the first meeting, the core project team ran a workshop (on which PWG members provided feedback) introducing theoretical and pedagogical considerations for dialogic teaching. Subsequent meetings, which occurred in parallel to the implementation of the emerging dialogic teaching model, were designed to allow PWG members to share, reflect, and learn from each other based on their experiences implementing dialogic teaching in their own clinical contexts.

Some PWG members journaled about their educational encounters as they piloted dialogic techniques in clinical teaching—all were interviewed by a research associate (P.V.) twice over the following months. Interview questions prompted PWG members to reflect on their experiences of participating in the faculty development pilot and implementing dialogic teaching, including barriers and enablers, reception of the approach, and tips/tricks. In addition, P.V. kept detailed meeting notes and notes about implementation, including curriculum/pedagogy planning and resource development.

Over the course of 2 meetings (after each set of interviews), the core project team and the PWG iteratively co-analyzed data using a qualitative description approach17,18 within a constructivist paradigm, which asserts that the reality we perceive is constructed by our social, historical, and individual contexts.19 A qualitative description aims to offer a comprehensive summary of an event in the everyday terms of that event.17,18 This methodology facilitated our goal to provide a meaningful representation of the innovation by allowing us to stay close to the data, rather than imposing an external theoretical framework. To facilitate group analysis, data from participants' journals, interview transcripts, and implementation notes were first distilled into key themes. The PWG members worked with the core research team to analyze, refine, and incorporate these data into faculty development materials and clinical teaching resources. This ongoing analysis informed iterative changes to the faculty development program and dialogic teaching model. All PWG members contributed vocally to the process and were instrumental to the outcome of the pilot; they became sufficiently involved in the process to join the project team as co-investigators.

Patient and Learner Involvement

The core project team engaged patient advisers to provide feedback and guidance about our model for dialogic education as part of the strategy for the Person-Centred Care Education initiative overall. We used a public involvement mosaic16 framework to support feasible and meaningful involvement, where each adviser has the opportunity to provide targeted guidance related to a particular aspect of the project (Table). The framework enabled the creation of a network of patient advisers who could be brought together across different axes for collaboration and support. Initial patient advisers were recruited using the principal investigators' professional networks. Further, patients were recruited with the help of initial advisers. Patients were thanked for their input with a small honorarium from the department.

Table.

Patient Adviser Involvement Framework for Person-Centred Care Educationa

| Areas of Person-Centred Care Education | Processes | ||

| Design | Implementation | Evaluation | |

| Dialogic teaching and learning | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 |

| CanMEDS Knowledges Project | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 |

| Cultural safety curriculum | Patient 7 | Patient 8 | Patient 9 |

This framework is based on the public involvement mosaic of Gauvin and colleagues.16

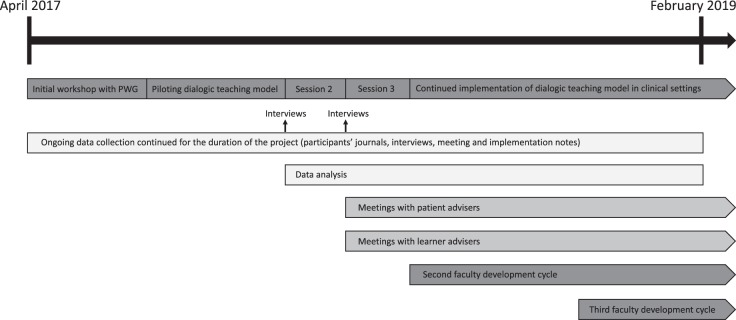

The core project team engaged resident learners as advisers with respect to the structure and feasibility of dialogic teaching and learning in their clinical settings. Initial advisers were Department of Medicine residents who responded to an open call for interested trainees. See the Figure for the project timeline.

Figure.

Project Timeline

The study was approved by the University of Toronto Institutional Review Board.

Results

The faculty development program and dialogic teaching model were developed iteratively and concurrently in collaboration with the PWG. Patient and learner advisers further contributed to the model. First, we present PWG members' experiences of this process, grouped according to enablers to dialogic teaching, challenges to dialogic teaching, and next steps for faculty development rollout. Second, we describe the contributions of patient and learner advisers. See Box 1 for representative excerpts from interviews with PWG members; these themes were consistent across the data sources.

box 1 Examples of Quotes From Interviews With Pilot Working Group (PWG) Members.

Enablers to dialogic teaching

I remember back to the stories that we were sharing with each other during the [second PWG meeting]. And, just, recalling the enthusiasm people had and, you know, some of the discussions we had, that I would not otherwise consider to be a potential learning moment. You know, so it's more about a recollection or a memory of what was discussed during the meeting [that enabled dialogic teaching]. —PWG member 105

I kind of see this as a bit more of an artistry about teaching, probably more so than other ways of teaching and facilitating learning. And, from that perspective, it's, I think, . . . for me at least, [it's] going to come from just hearing how others have done it. —PWG member 105

It's really just a matter of paying attention and just identifying, you know, different kind of discussion . . . . So I think the most important is to increase overall awareness that this is also extremely important in terms of teaching moments for the trainees. Because once there is an awareness and almost a permission to have [dialogues] as part of the daily teaching . . . . So I think the most important enabler is really having an awareness of the situations that could lead to those kind of discussions. —PWG member 107

The actual label of dialogic teaching I was not aware about. . . . So I think it was a bit of an endorsement, and I felt good that I'm doing something which has a theoretical background, or a research background, and there's a name for it. —PWG member 003

Barriers to dialogic teaching

You have to make time for back and forth with the trainees and the student. So, make time for them to help co-construct knowledge. That is, I don't know if maybe it's my skill in teaching this way, but I feel like that takes more time than me sort of more Socratically taking the group through even a similar type concept. —PWG member 104

Separating that time from care is an issue in a workplace that is under incredible stress right now. Those of us who are in teaching hospitals are aware that our occupancy runs about 110% to 120% all the time. So, quite often, there's not even a private place to go to have these kinds of discussions. Hallways are filled with patients on stretchers. . . . So, I think it's a systems issue. —PWG member 101

I think it's still not, just really, you know, a natural and spontaneous way of teaching. . . . I do clinical work and therefore bedside teaching intermittently … . So it's a bit hard to get into a habit, or at least, I haven't managed that. So I need to be quite purposeful about trying to integrate that kind of teaching in the mainly kind of clinical activities. —PWG member 107

The ongoing challenge for me is how am I going to be seen? Because we work in a world where a lot of how we're judged is based on the perceptions of the learners . . . . This is probably where some of the artistry comes in; where, I mean, does one have to come at the expense of the other? I don't know. There probably is a way to have a comfortable merge between 2 different styles of teaching and learning, but I just haven't figured that out yet.—PWG member 105

Next steps

You know, that's a little bit of a tough battle . . . because some people will say, you know what, this is too theoretical for me. . . . So I think we as a group . . . need to champion it a bit. And the good thing is we have a buy-in from the higher stakeholders . . . . So I think that gives us some credibility. But it is a change in culture, which I think will take some longer time. —PWG member 003

For me, this is an opportunity to reframe in my mind stuff I felt like I was already doing, and I think most of my colleagues are probably doing the same, whether they recognize it as dialogic teaching or not. There may be some for whom this whole framework will be a bit of a challenge . . . . I think that, you know, we could move . . . with a greater timeline to roll out. —PWG member 006

I think if this movement is going to be successful, there has to be more exposure to the concept, such as [A.K. and L.R.] doing the grand medical rounds on the topic in each institution and then maybe there would be a few people in the audience who would show interest. And then they would become part of the next group. Because I think it's a gradual sell. . . . And, so, keeping our groups alive in our individual institutions is going to be really important.—PWG member 105

I actually think the face-to-face meetings are going to be a wonderful mechanism to support the role of dialogic teaching. I do think you need to have people in the room like me who are enthusiastic about it, who are using it, who know it makes a difference . . . . It's all about showing people that it's not that difficult. —PWG member 001

The concepts and practice of dialogic teaching resonated with PWG members. However, even this carefully selected group indicated that dialogic teaching was easier to learn about than to implement in practice. It took several months for some to become comfortable using these methods, in part because they were met with skepticism by some faculty and learners who were used to more traditional teaching approaches. For some, this way of teaching came naturally, while others said they had to work to shift their usual teaching style.

The PWG members found that having the opportunity to periodically share ideas and motivate each other at the faculty development meetings was helpful in facilitating their provision of dialogic teaching; they also appreciated the support and expertise of the core project team. Some indicated that having a label for what they were doing, backed by theory, research, and a formal departmental program, afforded them confidence in teaching dialogically and provided credibility when they were questioned about it by trainees or colleagues. Some PWG members decided to look for dialogic teaching opportunities in every patient encounter, whereas others found it easier to teach dialogically around issues arising for specific, often structurally marginalized, groups of patients. Some also noted that dialogic teaching sometimes became easier over time with longitudinal trainees. The PWG members requested the development of practical teaching resources (eg, a tip sheet) and found these to be helpful when provided (Box 2).

box 2 Tip Sheet of Ideas and Prompts for Dialogic Teaching.

Create space for dialogue

Build time into existing structures (eg, a half-hour on Thursdays after rounds) or allow it to happen spontaneously.

Make dialogue habitual and deliberate (eg, initiate a dialogue with a learner at least once during every clinic).

Determine whether the dialogue should be explicitly labeled or more implicit, depending on the context. Sometimes you may want to specifically signal when you are having a dialogue and label it as teaching (eg, “I'm now going to change the focus of my teaching to consider other factors in the care of our patient”).

Establish a safe and open learning environment

Deconstruct the teacher-learner hierarchy. Create an awareness of the other as an equal relational partner by sharing authority, expertise, and perspectives (eg, share a story from your own practice first to model vulnerability to learners).

Embrace uncertainty (eg, have confidence as a teacher to say, “I don't know, but we can discover together”).

Practice self-questioning (eg, “I think I just used this term [that makes me uncomfortable when I think about it more]. Why is this language so enculturated in me?”).

Ensure that responses to learners are nonjudgmental (verbal and nonverbal).

Learn to be comfortable with silence to give the learner time to respond to a question.

Engage in dialogue with learners

Pose questions that allow learners to acknowledge how patients affect them and to explore their subjective reactions to patients (eg, asking “Why do we feel the need to have control over our patients—or to have all the answers?” gets at the sense of feeling powerless to help a patient).

Use the notion of making strange. Pose questions about usual practices that prompt oneself and the learner to challenge assumptions and look at things in a new way (eg, challenge learners about the guilt we place on patients by labeling them as “noncompliant”).

Spark wonder. Ask learners questions that stimulate a sense of wonderment and an awareness of the mystery of the human condition (eg, “I wonder how Jim is managing to pay for his medication?” “Wow, can you believe that kind of thing really happened to someone in our town?” or “You know, I wonder why this family member is so angry.”).

Question biases and expectations (eg, “What is your expectation of a good patient?” or “What do we mean when we say a family is ‘reasonable' or ‘difficult'”?).

Reflect on moments of daily practice (eg, “Why do you think that interaction with the patient didn't go so well for us?”).

Ask questions that make use of everyday paradoxes (eg, “How come we focus on educating patients to be compliant with their diabetes care when we know they can't afford their insulin?”).

Draw attention to the language we use and consider how labels determine a patient's journey. When we catch ourselves using language in this way, acknowledge that no one is perfect and role model how to apologize and commit to change. Wonder aloud about why we use that language at all (eg, “failure to cope,” “bed blockers,” and metonymic metaphors when the disease becomes the person [ie, the COPD-er, the diabetic foot in bed 3]).

Share a “story with no end,” such as a challenging ethical situation, and then ask the learner to imagine a possible ending.

Give learners space to come up with their own ideas (eg, post a question at the end of clinic and ask the learner to reflect on it and then discuss during your next encounter).

Find a balance between mechanics (scripted questions) and artistry/creativity.

Encourage learners to engage in dialogue with patients

Remind learners of the basics of person-centered care. This includes saying phrases like “Hello my name is . . . and my role is . . .” at a pace and volume that is accessible to patients.

Encourage learners to open the patient encounter by asking the patient a question that invites them to tell a story (eg, “I'm sorry for the wait, what have you been doing while you've been waiting?”).

Encourage learners to give patients permission to articulate their feelings by asking open-ended questions while paying attention to context and underlying issues (eg, “Is there something else that's troubling you?” or “What's your most important worry at the moment?”).

Prompt learners to ask the patient about his or her goals (eg, “What do you hope to get out this visit?”).

The PWG members also identified barriers to dialogic teaching. Nonhierarchical, affective, open-ended teaching can take time, and PWG members were challenged by competing clinical responsibilities, busy residents with whom they only interacted briefly, and insufficient time for teaching in general. Lack of a private space on inpatient wards where learners could feel safe to speak freely was also identified as an issue. Some PWG members were initially concerned about a decline in their formal teaching evaluation scores from trainees if they taught dialogically, but by the end of the pilot most of those concerns had been allayed by positive teaching experiences. Importantly, PWG members emphasized the value of explicitly labeling dialogic moments for trainees as “teaching” and acknowledging and debriefing faculty and resident discomfort when it occurred.

In addition, PWG members contributed to a plan for continued rollout of the program. There was general consensus that not all faculty members would initially be comfortable using dialogic approaches. However, most PWG members indicated that their colleagues were supportive as long as trainees were also being exposed to traditional bioscientific clinical content. They suggested a slow rollout and a multipronged approach to knowledge dissemination, such as through medical grand rounds and departmental newsletters and web pages. The PWG members were optimistic that an ongoing rollout to interested faculty, combined with increasing exposure of trainees (ie, future faculty) to these ideas through being taught dialogically, would eventually lead to pedagogical and cultural change in the department.

After the PWG process was complete, we sent open calls to all Department of Medicine physicians for a second and third 2-session faculty development program that had been reconstructed based on PWG member input. We are creating a network of colleagues across the department who use dialogic teaching methods at the bedside in their day-to-day practice.

Patient and Learner Involvement

In keeping with our patient involvement framework, we met with 3 patient advisers who provided important initial insights to deepen the design, implementation, and eventual evaluation of our dialogic education model; they have agreed to continue to advise us. Each adviser's insights were recognized and interpreted as a single, unique perspective on a spectrum of human experiences related to illness, rather than a perspective considered typical of a broader patient experience.20

We discovered from initial one-on-one meetings that residents also wanted to learn to teach dialogically. We therefore restructured a planned learner advisory circle as an educational opportunity. All interested residents were invited, and 21 attended. Learners subsequently requested a nonhierarchical joint session with faculty from the PWG and subsequent faculty development cohorts in which participants further contributed to the dialogic teaching model by sharing insights and challenges.

Discussion

The dialogic structure of the faculty development meetings and the legitimacy afforded by a formal label for the approach were important enablers of dialogic teaching in clinical settings. In contrast, insufficient time, lack of space, and other structural issues challenged the enactment of the approach. A multipronged and gradual strategy for continued faculty development rollout, paired with trainees' increasing exposure to dialogues, will help facilitate a pedagogical and cultural shift toward dialogic approaches to graduate medical education within the Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto.

Our approach to dialogic teaching is intended to be transferrable beyond our department. The results of our project demonstrate that it is feasible to teach busy physicians how to incorporate dialogic teaching into real-time, situated contexts of clinical care. This does, however, require the presence of at least a small number of faculty members who are trained to provide humanistic, person-centered care and have a grasp of the relevant pedagogy.1–3,5–7 In our project, several members of the core project team were content experts in the theory and practice of dialogic teaching as well as frontline physician teachers. The PWG members were experienced physician teachers who brought some content knowledge, as well as their own unique knowledge, skills, and experiences. Consequently, we were able to bring those perspectives and experiences together to collaboratively determine and refine the core knowledge, skills, and support faculty need to integrate dialogues into clinical teaching.

The feasibility and sustainability of this project also reflects our institutional culture, which includes an openness to hiring and supporting sufficient educators and researchers in this area to develop a community of practice, as well as its strategic priorities that legitimize person-centered, compassion-oriented teaching. A challenge in enabling and promoting this educational approach is the requirement of expertise, willingness, and support to teach content knowledge not traditionally included in medical curricula, such as knowledge from the social sciences and humanities.12 Meaningfully implementing bedside dialogic teaching also required a substantial amount of resources. The project received $25,000 in external grant funding from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation, which our department matched with measurable salary and administrative support. This enabled protected time of up to half a day per week for the principal investigators (A.K. and L.R.). The project leveraged approximately $5,000 from other grant funding related to the Person-Centred Care Education initiative for research support, including institutional review board amendments and data collection and analysis. In addition, the project benefited from volunteer and paid work by medical and undergraduate students working with the principal investigators, as well as in-kind support, such as meeting space and equipment from their research center and the department.

The findings of the study may be limited, as initial faculty participants were self-selected volunteers who already had an interest in humanistic approaches to education, such as dialogic teaching. Another important limitation is that the study took place at a single institution; however, there are likely many other departments and faculties of medicine with faculty members who could teach and learn this sort of material if given the opportunity.

As a next step, we have begun to work on developing appropriate assessment and evaluation strategies for dialogic teaching and learning (which do not yet exist in the literature). The clear delineation of the knowledge and skills required by faculty to teach dialogically has helped build an understanding of the construct as we begin to consider conceptual issues related to its assessment and evaluation.

Conclusion

While initial faculty participants found that the faculty development program supported the implementation of dialogic teaching in clinical contexts, successfully enabling and promoting this educational approach requires the expertise, willingness, and support to teach knowledge and skills that are not traditionally included in medical curricula.

References

- 1.Kumagai AK, Richardson L, Khan S, Kuper A. Dialogues on the threshold: dialogical learning for humanism and justice. Acad Med. 2018;93(12):1778–1783. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumagai AK, Naidu T. Reflection, dialogue, and the possibilities of space. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):283–288. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng SL, Wright SR, Kuper A. The divergence and convergence of critical reflection and critical reflexivity: implications for health professions education. Acad Med. 2019 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002724. published online ahead of print March 26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Woolf V. A sketch of the past. In: Schulkind J, editor. Moments of Being 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Press; 1985. pp. 61–159. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wear D, Zarconi J, Kumagai A, Cole-Kelly K. Slow medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):289–293. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad Med. 2009;84(6):782–787. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halman M, Baker L, Ng S. Using critical consciousness to inform health professions education: a literature review. Perspect Med Educ. 2017;6(1):12–20. doi: 10.1007/s40037-016-0324-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakhtin M, Holquist M. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakhtin M, Holquist M, Emerson C. Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank AW. What is dialogical research, and why should we do it? Qual Health Res. 2005;15(7):964–974. doi: 10.1177/1049732305279078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haraway D. Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem Stud. 1988;14(3):575–599. doi: 10.2307/3178066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuper A, Veinot P, Leavitt J, Levitt S, Li A, Goguen J, et al. Epistemology, culture, justice and power: non-bioscientific knowledge for medical training. Med Educ. 2017;51(2):158–173. doi: 10.1111/medu.13115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smye V, Josewski V, Kendall E. Ottawa: First Nations, Inuit and Métis Advisory Committee, Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2010. Cultural safety: an overview. http://www.troubleshumeur.ca/documents/Publications/CULTURAL%20SAFETY%20AN%20OVERVIEW%20%28draft%20mar%202010%29.pdf Accessed May 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramsden I. Cultural safety. N Z Nurs J. 1990;83(11):18–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papps E, Ramsden I. Cultural safety in nursing: the New Zealand experience. Int J Qual Health Care. 1996;8(5):491–497. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/8.5.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gauvin FP, Abelson J, Giacomini M, Eyles J, Lavis JN. “It all depends”: conceptualizing public involvement in the context of health technology assessment agencies. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(10):1518–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Heal. 2000;23(4):334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandelowski M. What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(1):77–84. doi: 10.1002/nur.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuper A, Reeves S, Levinson W. An introduction to reading and appraising qualitative research. BMJ. 2008;337:a288. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowland P, Kumagai AK. Dilemmas of representation: patient engagement in health professions education. Acad Med. 2018;93(6):869–873. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]