Abstract

Introduction:

Ongoing surveillance of youth substance use is essential to quantify harms and to identify populations at higher risk. In the Canadian context, historical and structural injustices make monitoring excess risk among Indigenous youth particularly important. This study updated national prevalence rates of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use among Indigenous and non-Indigenous students.

Methods:

Differences in tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use were examined, using logistic regression, among 1700 Indigenous and 22 800 non-Indigenous youth in Grades 9–12 who participated in the 2014/15 Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey. Differences by sex were also examined. Mean age of first alcohol and marijuana use was compared in the two populations using OLS regression. Results were compared to 2008/09 data.

Results:

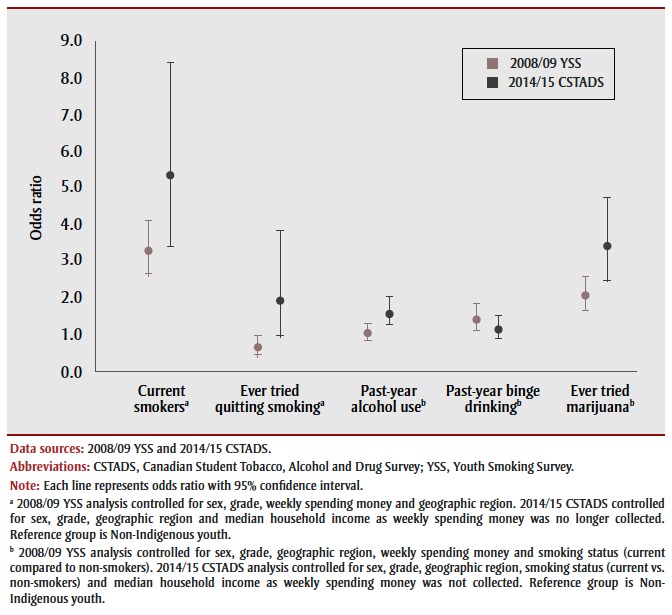

While smoking, alcohol, and marijuana rates have decreased compared to 2008/09 in both populations, the gap between the populations has mostly not. In 2014/15, Indigenous youth had higher odds of smoking (odds ratio [OR]: 5.26; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.54–7.81) and past-year drinking (OR: 1.43; 95% CI: 1.16– 1.76) than non-Indigenous youth. More Indigenous than non-Indigenous youth attempted quitting smoking. Non-Indigenous males were less likely to have had at least one drink in the past-year compared to non-Indigenous females. Indigenous males and females had higher odds of past-year marijuana use than non-Indigenous males (OR: 1.84; 95% CI: 1.32–2.56) and females (OR: 2.87; 95% CI: 2.15–3.84). Indigenous youth, especially males, drank alcohol and used marijuana at younger ages.

Conclusion:

Additional policies and programs are required to help Indigenous youth be successful in their attempts to quit smoking, and to address high rates of alcohol and marijuana use.

Keywords: adolescent, alcohol drinking, smoking, cannabis smoking, Indigenous population

Highlights

Despite decreased prevalence of smoking and increased attempts to quit, Indigenous youth had more than 5 times higher odds of being smokers compared to non-Indigenous youth.

Indigenous youth, especially males, drank alcohol and used marijuana at a younger age compared to non- Indigenous youth.

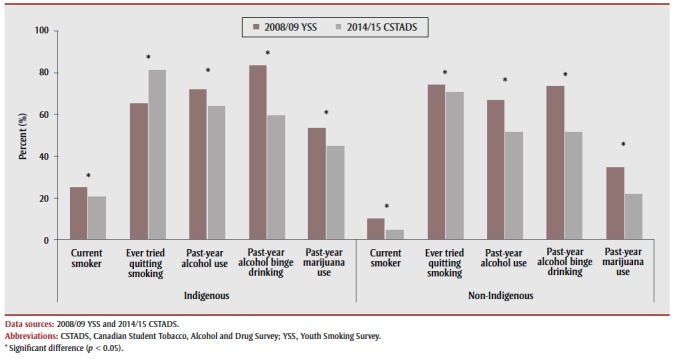

Compared to 2008/09, rates of pastyear alcohol use, binge drinking, and marijuana use decreased in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth in 2014/15. Binge drinking decreased the most, by about 30% in both populations.

Indigenous males had 1.8 higher odds of past-year marijuana use compared to non-Indigenous males, whereas females had 2.8 times higher odds compared to non- Indigenous females.

Introduction

There is evidence that Indigenous youth are more likely than other Canadian youth to use tobacco, alcohol and marijuana.1-10

The reasons for this higher risk are complex, but social factors that potentially contribute include marginalization, the experience of discrimination, intergenerational trauma, financial hardships, and familial separation.2,5 For example, adverse childhood and adolescence experiences such as sexual and physical abuse, household mental illness, and household substance use have been linked to substance use among Indigenous adolescents in British Columbia.9 When children and youth are chronically exposed to stressful environments, their neurodevelopment and cognitive functioning can be impaired, potentially contributing to the adoption of negative coping behaviours, such as substance use.2,11 High prevalence of substance use could also lead to its normalization in schools or communities, potentially perpetuating a cycle of use among youth.5

Understanding health inequities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth is important, especially considering that Indigenous populations are the youngest and fastest growing ethnically defined populations in Canada.13 According to the 2016 census, self-identified First Nations, Inuit and Métis represented 4.9% of the total Canadian population,12,13 and 16.9% were 15 to 24 years old, compared to 12.0% of the non-Indigenous population. 14 The total Indigenous identity population in Canada increased by 43% between 2006 to 2016, while the non- Indigenous population grew 9%.14 Although substance use has been found to be high among First Nations youth living in First Nations communities,2 in 2016, 79.1% of Indigenous youth aged 15 to 24 lived outside of First Nations reserves.15 In the provinces, this includes a majority of Métis, who have not been part of treaties or the reserve system, as well as large proportions of both Status and non-Status First Nations.15 Attention to the well-being of these young people is therefore essential to promoting the health of Indigenous populations and the Canadian population in general.

There are numerous health risks associated with smoking, alcohol, and marijuana use, especially for youth.16-20 For example, the Canadian census mortality follow-up study found the risk of death from tobacco smoking-related causes was 75% higher among Métis females and 14% higher among Métis males when compared to non-Indigenous females and males.21 Despite some evidence of high rates of drug use among Indigenous youth, there has been limited research on patterns of substance use.22 This study compared patterns of tobacco, alcohol and marijuana use among Indigenous youth attending off-reserve schools to non-Indigenous youth using nationally representative data from the 2014/15 Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey23 (CSTADS; formerly known as the Youth Smoking Survey [YSS]). The primary objective of this study was to update the analysis of Elton-Marshall et al.1 who previously examined substance use in Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth using the 2008/09 YSS. Where possible, data from 2014/15 were compared to their results.

Methods

Research design

Cross-sectional data were obtained from 24 500 students in Grades 9 to 12 from 336 schools who responded to the 2014/15 CSTADS and reported ethnicity.23 CSTADS is a nationally representative school-based survey of youth in Canada that collects data on tobacco, alcohol, and drug use. In 2014/15, it included youth attending private, public, and Catholic schools in nine of Canada’s provinces. Schools in New Brunswick, Yukon, Nunavut, and the Northwest Territories were excluded. Youth living in institutions or attending special schools, First Nation reserve schools, or schools on Canadian Armed Forces bases were also not sampled. The sample was stratified on health region smoking rates and within each province schools were randomly selected based on their total enrollment of students. While CSTADS includes students in Grades 6 to 12, only those in Grades 9 to 12 were included in this study as secondary school students are more likely to engage in substance use. The overall participation rate was 49% of sampled school boards, 47% of sampled schools, and 66% of sampled students.

Research ethics approval for CSTADS was obtained with the University of Waterloo Human Research Ethics Committee (ORE #19531), the Health Canada/Public Health Agency of Canada Research Ethics Board (#REB 2009-0060) and from individual school boards or other appropriate bodies.

Measures

Indigeneity in the 2014/15 CSTADS was self-reported, using the question, “How would you describe yourself? (Mark all that apply).” Possible responses included White, Black, West Asian/Arab, South Asian, East/Southeast Asian, Latin American/ Hispanic, Aboriginal (First Nations, Métis, Inuit, …), and Other (write-in). Although “Indigenous” has become a generally preferred term, “Aboriginal” was used on the 2014/15 CSTADS questionnaire, as in the 2016 Census,12 following the terminology of the 1982 Constitution Act. Sex was assessed with a single question, “are you female or male”, with binary responses.

Consistent with Health Canada’s definition, a “current smoker” is someone who has smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and at least one whole cigarette in the past 30 days.24 A “former smoker” has smoked at least 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime, but has not smoked in the past 30 days.24 A “non-smoker” has not smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetime but may have smoked one whole cigarette.24 Past-year prevalence of alcohol, binge drinking, and marijuana use are also reported. Consistent with previous studies, binge drinking is defined as having five or more drinks on one occasion.1,2

Statistical analysis

Survey weights were used to provide population- level estimates of substance use. Bootstrap weights, which were used for calculating prevalence estimates and regression analyses, account for the effects of survey design on variance estimates.

Differences between Indigenous and non- Indigenous youth in the average age at first alcohol and marijuana use were assessed using Ordinary Least Squares regression. Differences in substance use by Indigenous ethnicity and sex were tested using binary logistic regression. Each model was assessed for the possibility that effects might be modified by one of several possible cofactors: sex, grade, and smoking status (former smokers excluded for the alcohol and marijuana analyses), median 2011 census Dissemination Area household income based on school location and geographic region. If any of these variables were found to be covariates (i.e., they changed the point estimate by more than 10%), they were included in the final model.25-26 All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The CSTADS participants in Grades 9 to 12 included 24 500 students (a weighted population of 1 500 900 students), with an estimated 1700 (weighted sample of 70 000) who reported being Indigenous (“Aboriginal”) (Table 1). The student sample included 12.9% from British Columbia, 6.7% from Atlantic Canada, 46.4% from Ontario, 15.9% from Québec, and 17.1% from the Canadian Prairies. Table 2 presents the association between Indigenous ethnicity and sex, and substance use behaviours.

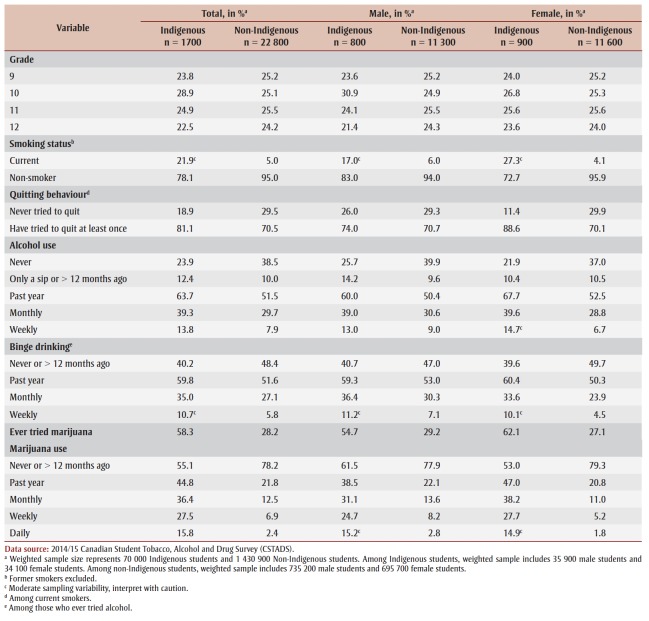

Table 1. Weighted sample characteristics, by sex and Indigenous ethnicity, grade 9–12 students, 2014/15.

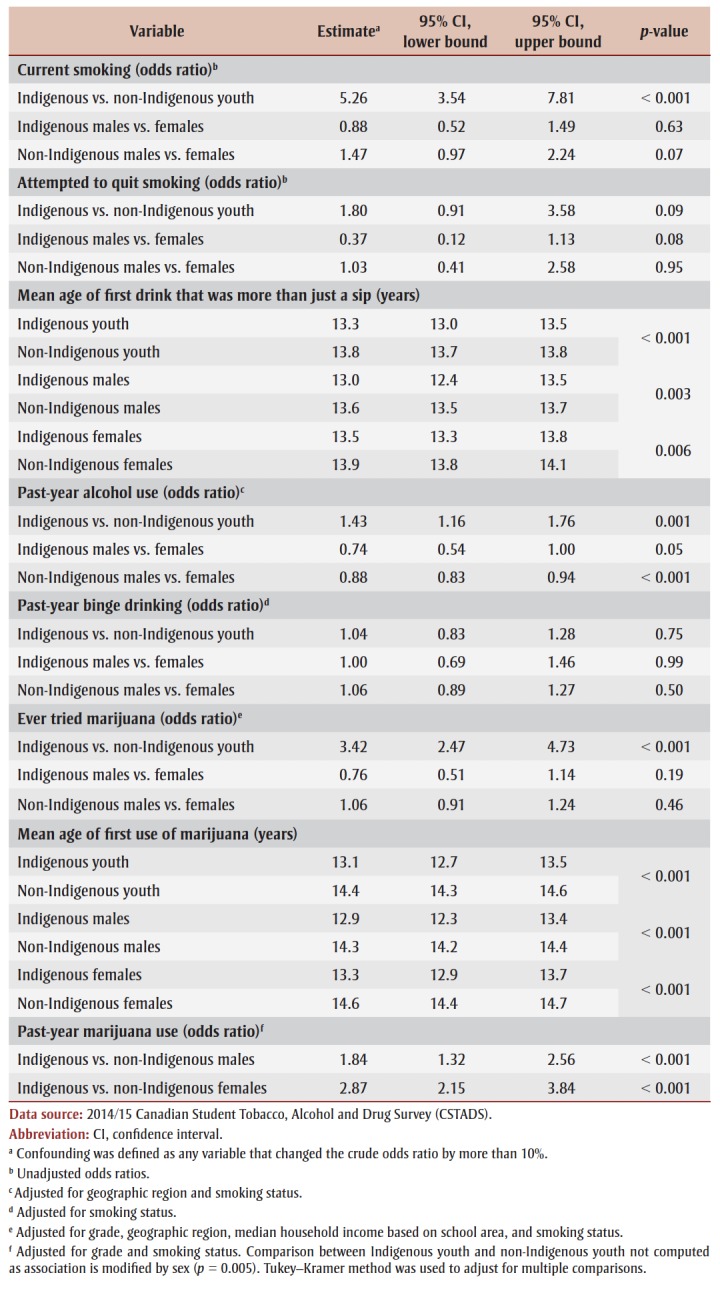

Table 2. Measures of substance use behaviours by Indigenous ethnicity and sex, grade 9–12 students, 2014/15.

|

Tobacco use

Indigenous youth were significantly more likely than non-Indigenous youth to be current smokers (odds ratio [OR]: 5.26; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.54–7.81) (Table 2). Among both Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth, males and females were not significantly different in their odds of smoking. Among smokers, Indigenous youth were more likely than non-Indigenous youth to have ever tried to quit (OR: 1.80; 95% CI: 0.91–3.58). Males and females were equally likely to have attempted to quit smoking among Indigenous youth and non-Indigenous youth (Table 2).

Alcohol use

Indigenous youth were more likely than non-Indigenous youth to report having used alcohol in the previous year (OR: 1.43; 95% CI: 1.16–1.76), after controlling for geographic region and smoking status, which were found to be confounders (Table 2). Indigenous males were 26% less likely to have engaged in past-year alcohol use (OR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.54–1.0) compared to Indigenous females, a borderline statistically significant trend. Among non-Indigenous students, males were 12% less likely to have engaged in pastyear alcohol use (OR: 0.88; 95% CI: 0.83– 0.94) compared to females, after adjusting for geographic region and smoking status.

On average, Indigenous youth reported beginning drinking at slightly younger ages than did non-Indigenous students (Indigenous: 13.3 years, 95% CI: 13.0– 13.5; non-Indigenous: 13.8 years, 95% CI: 13.7–13.8) (Table 2). In both populations, males begun drinking alcohol at a younger age than females (Table 2). There was no significant difference between the two populations in past-year binge drinking (OR: 1.04; 95% CI: 0.83–1.28), after controlling for smoking status. There were no significant differences in past-year binge drinking by sex among Indigenous youth or non-Indigenous youth, after adjusting for smoking status.

Marijuana use

Indigenous youth were more likely than non-Indigenous youth to have ever tried marijuana (OR: 3.42; 95% CI: 2.47–4.73), after adjusting for grade, region, median household income and tobacco smoking status (Table 2). Sex was a statistically significant modifier of the association between Indigeneity and past-year marijuana use (p = 0.005). Indigenous males were more likely to have used marijuana in the past year compared to non-Indigenous males (OR: 1.84; 95% CI: 1.32–2.56), and Indigenous females were almost three times more likely than non-Indigenous females to have used marijuana in the past year (OR: 2.87; 95% CI: 2.15–3.84), after controlling for grade and smoking status. Indigenous youth reported using marijuana at a younger age (mean 13.1 years; 95% CI: 12.7–13.5) than non-Indigenous youth (mean 14.4 years; 95% CI: 14.3–14.6) (Table 2). Males reported having begun using marijuana at a younger age than females among both populations.

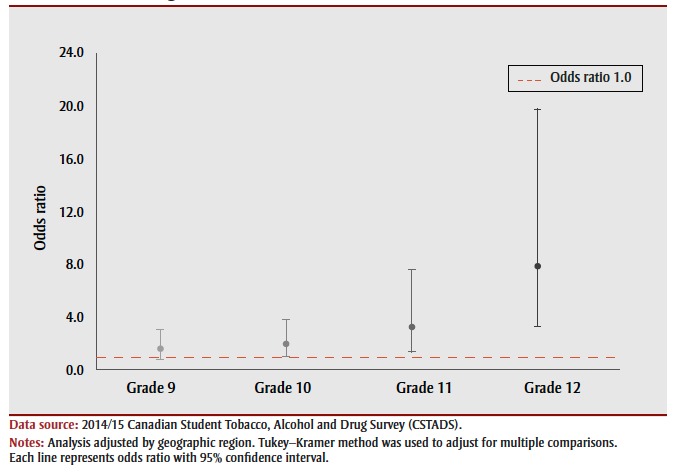

Overall, among those who used marijuana during the past year, 15.8% of Indigenous students and 2.4% of non-Indigenous students in Grades 9 to 12 reported daily use. This association differed by grade, with no differences by sex. Among students in Grade 9, there was no difference in pastyear marijuana use between the two populations. Indigenous youth were twice as likely to have used marijuana daily (OR: 2.05; 95% CI: 1.08–3.91) when in Grade 10 and three times more likely when in Grade 11 (OR: 3.30; 95% CI: 1.42–7.68). The association was most pronounced among Grade 12 students, where Indigenous youth had over eight times higher odds of daily marijuana use (OR: 8.12; 95% CI: 3.33–19.78), compared to non-Indigenous youth (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Odds of using marijuana daily, Indigenous youth compared to non-Indigenous students in grades 9–12, 95% confidence intervals, 2014/15.

Changes over time – 2008/09 to 2014/15

Differences in prevalence of use from 2014/15 CSTADS were compared to results previously published from the 2008/09 YSS (Figure 2).1 CSTADS data are considered comparable to 2008/09 YSS data.27 Between 2008/09 and 2014/15, the estimated prevalence of smoking decreased by 17.7% in Indigenous youth (24.9% to 20.5%) and 54.8% in non-Indigenous youth (10.4% to 4.7%). Among smokers, the proportion of non-Indigenous youth that attempted to quit smoking decreased by 5.1% (74.3% to 70.5%), while among Indigenous youth it increased by 23.6% (65.6% to 81.1%). Past-year alcohol use decreased by 11.4% (from 71.9% to 63.7%) among Indigenous and 22.8% (from 66.7% to 51.5%) among non-Indigenous youth, along with past-year binge drinking, which decreased in both groups; by 28.3% (from 83.4% to 59.8%) in Indigenous and 30.1% (from 73.8% to 51.6%) in non-Indigenous youth. Pastyear marijuana use decreased by 15.8% (from 53.2% to 44.8%) among Indigenous students and 36.8% (34.5% to 21.8%) among non-Indigenous students. All 2008/09 to 2014/15 changes were statistically significant.

Figure 2. Prevalence of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use among students in grades 9– 12 by Indigenous ethnicity, 2008/09 and 2014/15.

Between 2008/09 and 2014/15, there were some changes in the role of sex in predicting substance use by Indigenous students. In 2008/09, the prevalence of smoking, quitting attempts, and alcohol and marijuana use was higher among female than among male Indigenous youth. In 2014/15, neither smoking nor quitting attempts differed significantly by sex. In 2014/15, as in 2008/09, female Indigenous youth reported higher past-year alcohol and marijuana use than did males.

In addition to changes in prevalence of substance use within both groups, the gap between the groups was examined (Figure 3). In 2008/09, Indigenous youth had 3.3 times higher odds of being current smokers relative to non-Indigenous youth, while in 2014/15 Indigenous youth had 5.3 higher odds. Notably, Indigenous youth went from being 35% less likely to attempt quitting in 2008/09, to 92% more likely to attempt quitting smoking. Indigenous youth went from being 41% more likely to engage in past-year binge drinking in 2008/09 to binge drinking at the same level as non-Indigenous youth in 2014/15. While past-year alcohol use was the same between the two populations in 2008/09, in 2014/15, Indigenous youth had 58% higher odds of past-year alcohol use when compared to non-Indigenous youth. In 2008/09, Indigenous youth were twice as likely to have ever tried marijuana, while in 2014/15, they were almost three and a half times as likely compared to non- Indigenous youth.

Figure 3. Tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use in Indigenous students compared to Non-Indigenous students, grades 9–12, 2008/09 and 2014/15.

Discussion

The analysis of 2014/15 CSTADS data showed some important differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth on some substance use behaviours, but not on others. Indigenous youth were more likely to have smoked, used alcohol, and used marijuana in year preceding the survey, than were non-Indigenous youth. However, among current smokers, Indigenous youth were also more likely to have attempted quitting. Both populations were equally likely to have engaged in past-year binge drinking, with no differences by sex. On average, Indigenous youth reported starting drinking alcohol and using marijuana at younger ages. In both populations, males began drinking alcohol and using marijuana at a younger age than females. Past-year marijuana use differed by sex, with females reporting significantly higher rates. Daily marijuana was significantly higher among Indigenous youth relative to non-Indigenous youth, but only among students in Grades 10 to 12.

Indigenous youth were substantially more likely than the general youth population to be current smokers, and while they were more likely to attempt quitting, additional resources are needed to help this population take the desire to quit into action. This same conclusion was made by Elton-Marshall et al.1 using 2008/09 data, suggesting that current tobacco control strategies are not enough for this high-risk population.5

This high rate of smoking among Indigenous youth is concerning. Moreover, it is possible that it is an underestimation of the true risk. To be considered a current smoker by Health Canada, youth must have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and smoked at least one whole cigarette in the past 30 days.1,5,24 While this definition has been used across multiple studies in both youth and adult populations, it might not be appropriate for youth.28 Compared to adults, youth have a higher sensitivity to nicotine resulting in earlier dependence and higher risk of developing severe nicotine addiction.28 Higher sensitivity to nicotine, indicates that fewer cigarettes would need to be smoked to generate the same effects seen in adults.28

There is evidence that cessation interventions are effective in Indigenous populations, though the optimum method of employment and whether culturally-adapted interventions are necessary is not well known.29 Limited evidence from a Cochrane review and a global systematic review suggests that culturally-adapted interventions can result in abstinence.28-31 Interventions that include community engagement, Indigenous leadership, and the use of materials and activities that are designed considering culture and values were found to be the most beneficial.30-31 Aggressive media campaigns, increasing cigarette price, specific adolescent cessation programs have also been found to be effective prevention control strategies in the general population.32 Indigenous youth are primarily influenced by peers and household members to initiate smoking.4 Given that a supportive home environment has been found to prevent smoking initiation in Indigenous youth, further evaluation and development of family and community-based interventions is warranted.4

A key consideration in intervention efforts should be the traditional use of tobacco by Indigenous populations during ceremonies and for medical purposes.4 This traditional use is not to be confused with tobacco misuse, where misuse refers to the recreational use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes, chewing tobacco, and pipes.4,33 During traditional use, inhalation is very minimal, as tobacco is typically ceremonially burned or placed on the ground as an offering or gift to establish a pathway to the spiritual world.4,33 Conversely, recreational use involves inhaling large amounts of commercial tobacco with high amounts of nicotine and other toxic chemicals. 4 Tobacco use is not traditionally sacred for all Indigenous groups and Inuit only began using tobacco about one hundred years ago.4 Non-traditional use of tobacco is often seen by Elders as disrespectful to Indigenous cultures and traditions.4,33

Smoking cessation programs targeted at Indigenous youth should therefore not portray all tobacco as negative, but rather make a clear distinction between sacred and recreational use.33 Elders in Indigenous communities can play a large part in the dissemination of this knowledge. Among Indigenous youth who have attempted to quit, 6% have reported doing so to respect the cultural significance of tobacco, while 76% reported quitting to attain a healthier lifestyle and due to heightened awareness of negative effects.2 The awareness of traditional tobacco use, in addition to the negative effects of commercial tobacco, might further increase attempts to quit and quitting effectiveness.

The public health focus on binge drinking might have proved beneficial as rates dropped by about 30% in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth, with no significant difference between the two populations. It is concerning that about a third of Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth engage in binge drinking monthly. CSTADS defines binge drinking as 5 or more drinks on one occasion for both males and females. This might lead to an underestimation of binge drinking in female youth as guidelines define binge drinking as 5 or more drinks on one occasion for males and 4 or more drinks on one occasion for females.34 The developing adolescent brain exhibits a higher degree of neuroplasticity when compared to the adult brain, a process highly sensitive to alcohol.35 As a result, youth may experience the negative health effects associated with binge drinking at lower doses.

While alcohol use has decreased over the past five years in both populations, Indigenous youth had a 43% higher odds of past-year alcohol use. Armenta et al.36 found that discrimination and positive drinking schemas were able to independently predict alcohol use in a sample of Indigenous youth in northern US and Canada. However, after controlling for discrimination, peer drinking and gender, the effect of positive drinking schemas was attenuated.36 These findings may help partially explain why in our study Indigenous youth began alcohol use earlier, particularly males. Both Indigenous and non- Indigenous youth, might have positive views on drinking alcohol. However, non- Indigenous youth are less likely to perceive that they have experienced discrimination. Youth with peers and household members who consume alcohol are also likely to have stronger positive drinking conceptions.5,36 As well as working to reduce the experience of systemic discrimination of Indigenous youth, incorporating the positive value of Indigenous identity into interventions could be useful to reduce the use of alcohol as a mechanism for coping with discrimination.36

Although past-year marijuana use decreased overall, Indigenous youth were significantly more likely to have used marijuana, especially among females. Daily marijuana use was substantially higher among Indigenous students at 15.8%, compared to 2.4% among non-Indigenous students. Previous research has shown that younger women tend to become regular cannabis users faster than men.37 However, in our study this was only observed among Indigenous females. This might be partly because Indigenous females first experience of marijuana was an average of 1.3 years earlier than non-Indigenous females and so they had a longer time to become regular cannabis users.

Management of harms is critical to protect these vulnerable youth populations as long term cannabis use can result in mental illness, chronic bronchitis, cancer, cognitive deficits and injuries.2,19 In a Canadian study examining the perception of cannabis among youth, many reported consuming cannabis to fit in with peers, to cope with stress, because it is easily accessible, for medical purposes, and because of limited side effects.38 When compared to other substances, youth viewed cannabis as the “safest”38,p.18 drug.38 Elders in some Indigenous communities have reported that cannabis can be used in culturally appropriate ways as a medicine and have stressed that for a medicine to be effective, it cannot be misused.39 To prevent harms, targeted prevention efforts in communities and schools might be necessary to alleviate misconceptions, including using the wisdom of Elders in Indigenous communities.

Limitations

Despite the large sample size and generalizability of the results to the population, this study has limitations. Data were selfreported, and therefore subject to recall bias. Given response rates were less than 67% at the school board, school, and student level, there is potential for nonresponse bias. Indigenous ethnicity was reported using a question that differs from the questions used in the Census of Canada to identify Indigenous ancestry or self-identity, and therefore this population might not be comparable to the census Indigenous populations.12-15 The question also does not allow disaggregation of First Nations, Métis and Inuit youth. CSTADS had no data on New Brunswick, Yukon Territory, Nunavut or the Northwest Territories, which decreases the generalizability of the study. The lack of Indigenous youth attending on-reserve schools is also a major limitation of this study. Although it is expected that most Indigenous youth in the sample also lived outside of reserves, it is possible that some lived in First Nations communities but attended schools off-reserve. Data on substance use among youth living in First Nations communities are available from other sources.2

Conclusion

Overall rates of tobacco, alcohol and marijuana use have decreased between 2008/09 and 2014/15 among both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students. There were no significant differences in past-year binge drinking between the two populations. In 2014/15, Indigenous students were five times more likely to have used tobacco, 50% more likely to have used alcohol and almost twice as likely to have used marijuana than non-Indigenous students. Indigenous youth were more likely to attempt quitting smoking. The continued higher rates of some substance use behaviours among Indigenous youth points to the importance of monitoring these behaviours and to inform policy on the needs of Indigenous youth outside of reserves.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Vicki Rynard and Robin Burkhalter from the University of Waterloo Propel Centre for Population Health Impact for their advice regarding data analysis. This research was funded under the Hallman Undergraduate Research Fellowship from the Faculty of Applied Health Sciences, University of Waterloo.

Data used for this research were taken from Health Canada’s Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CSTADS; formerly Youth Smoking Survey), which was conducted for Health Canada by the Propel Centre for Population Health Impact at the University of Waterloo. Health Canada has not reviewed, approved, nor endorsed this research. Any views expressed or conclusions drawn herein do not necessarily represent those of Health Canada.

Dr. Leatherdale is a Chair in Applied Public Health funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) in partnership with Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction (INMHA) and Institute of Population and Public Health (IPPH).

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Authors’ contributions and statement

CS conducted the analysis of data and drafted the article. All authors contributed to the design of the study, the interpretation of data, the revision of the article, provided final approval of the version to be published, and can act as guarantors of the work.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Elton-Marshall T, Leatherdale ST, Burkhalter R, et al. Tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug use among Aboriginal youth living off-reserve: results from the Youth Smoking Survey. CMAJ. :183(8):E480–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First Nations Information Governance Centre. Ottawa(ON): 2012. First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS) Phase 2 (2008/10) National report on adults, youth and children living in First Nations com¬munities [Internet] Available from: https://fnigc.ca/sites/default/files/docs/first_nations_regional_health_survey_rhs_2008-10_-_national_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Retnakaran R, Hanley AJ, Connelly PW, et al, et al. Cigarette smoking and car¬diovascular risk factors among Aboriginal Canadian youths. CMAJ. 2005;173((8)):885–9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.045159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetty R, et al. Tobacco use and misuse among Indigenous children and youth in Canada. Paediatr Child Health. 2017;22((7)):395–9. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxx124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elton-Marshall T, Leatherdale ST, Burkhalter R, et al, et al. Changes in tobacco use, susceptibility to future smoking, and quit attempts among Canadian youth over time: a compari¬son of off-reserve Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal youth. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10((2)):729–41. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10020729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie AJ, Reading JL, et al. Tobacco smoking status among Aboriginal youth. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2004:405–9. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v63i0.17945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu AW, Ratner PA, Johnson JL, et al. Gender differences in the correlates of adolescents' cannabis use. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43((10)):1438–63. doi: 10.1080/10826080802238140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenno JG, et al. Prince Albert youth drug and alcohol use: a comparison study of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, and Canada youth. Prince Albert youth drug and alcohol use: a comparison study of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, and Canada youth. Journal of Community Safety and Well-Being. 2016;1((3)):61–5. [Google Scholar]

- Woerd KA, Dixon BL, McDiarmid T, et al, et al. The McCreary Centre Society. Vancouver(BC): 2005. Raven's children II: Aboriginal youth health in BC [Internet] Available from: http://mcs.bc.ca/pdf/Ravens_children_2-web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Ottawa(ON): 2016. The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada, 2015: Alcohol Consumption in Canada [Internet] pp. Alcohol Consumption in Canada [Internet]–5. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/2015-alcohol-consumption-canada.html. [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, et al, et al. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics. 2003;111((3)):564–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): 2016. Aboriginal Peoples Highlight Tables, 2016 Census [Internet] Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/abo-aut/index-eng.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): 2017. Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025a-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): 2017. Aboriginal identity population by both sexes, total - age, 2016 counts, Canada, provinces and territories, 2016 Census – 25% Sample data [Internet] Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/abo-aut/Table.cfm?Lang=Eng&T=101&S=99&O=A. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): 2016. Aboriginal Identity (9), Residence by Aboriginal Geography (10), Registered or Treaty Indian Status (3), Age (20) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2016 Census - 25% Sample Data (Catalogue Number 98-400-X2016154) [Internet] Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/dt-td/Rp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=110443&PRID=10&PTYPE=109445&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2017&THEME=122&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF= [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Atlanta(GA): 2017. Health Effects of Cigarette Smoking [Internet] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Butt P, Gliksman L, Beirness D, Paradis C, Stockwell T, et al. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Ottawa(ON): 2011. Alcohol and health in Canada: a summary of evi¬dence and guidelines for low-risk drinking. Available from: http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/2011-Summary-of-Evidence-and-Guidelines-for-Low-Risk%20Drinking-en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Briasoulis A, Agarwal V, Messerli FH, et al. Alcohol consumption and the risk of hypertension in men and women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Hypertens. 2012;14((11)):792–8. doi: 10.1111/jch.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, et al. What has research over the past two decades revealed about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use. Addiction. 2015;110((1)):19–35. doi: 10.1111/add.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobus J, Tapert SF, et al. Effects of canna¬bis on the adolescent brain. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20((13)):2186–93. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjepkema M, Wilkins R, cal S, Penney C, et al. Mortality of Métis and registered Indian adults in Canada: an 11-year follow-up study. Health Rep. 2009;20((4)):31–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young TK, et al. Review of research on aboriginal populations in Canada: relevance to their health needs. BMJ. 2003;327((7412)):419–22. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7412.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Propel Centre for Population Health Impact. Waterloo(ON): 2010. Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey: Reports and results [Internet] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Ottawa(ON): 2014. Tobacco Use Statistics: Terminology [Internet] Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/tobacco/research/tobacco-use-statistics/terminology.html. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss R, Weinberg J, Webster T, Vieira V, et al. Determining the probability distri¬bution and evaluating sensitivity and false positive rate of a confounder detection method applied to logistic regression. Journal of Biometrics & Biostatistics. 2012;3((4)):142–22. doi: 10.4172/2155-6180.1000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado G, Greenland S, et al. Simulation study of confounder-selection strate¬gies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138((11)):923–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhalter R, Cumming T, Rynard V, Schonlau M, Manske S, et al. Propel Centre for Population Health Impact. Waterloo(ON): 2018. Research Methods for the Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey, 2010-2015 [Internet] Available from: https://uwaterloo.ca/canadian-student-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/sites/ca.canadian-student-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/files/uploads/files/report_researchmethodscstads_20180417.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta(GA): 2012. 2. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99242/ [Google Scholar]

- Chaiton M, Luk R, Yang W, et al, et al. Ontario Tobacco Research Unit. Toronto(ON): 2017. Smoke-Free Ontario OTRU Scientific Advisory Group evidence update 2017 [Internet] Available from: https://www.otru.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/special_sag.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Carson KV, Brinn MP, Peters M, et al, et al. Interventions for smoking cessation in Indigenous populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009046.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minichiello A, Lefkowitz AR, Firestone M, et al, et al. Effective strategies to reduce commercial tobacco use in Indigenous communities globally: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2015;16((1)):21–36. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2645-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PM, Jacobson PD, Warner KE, et al, et al. Investing in youth tobacco control: a review of smoking preven¬tion and control strategies. Tobacco Control. 2000;9((1)):47–63. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orisatoki R, et al. The public health impli¬cations of the use and misuse of tobacco among the Aboriginals in Canada. Glob J Health Sci. 2013:28–63. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n1p28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Research Translation and Communications, NIAAA. Bethesda(MD): 2004. NIAAA council approves defi¬nition of binge drinking. Available from: https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Newsletter/winter2004/Newsletter_Number3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP, et al. Adolescents and alcohol: acute sensitivities, enhanced intake, and later consequences. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2014:51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenta BE, Sittner KJ, Whitbeck LB, et al. Predicting the onset of alcohol use and the development of alcohol use disorder among indigenous adoles¬cents. Child Dev. 2016;87((3)):870–82. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis TS, Desai RA, Cavallo DA, et al, et al. Gender differences in adolescent marijuana use and associated psycho¬social characteristics. J Addict Med. 2011;5((1)):65–82. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181d8dc62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKiernan A, Fleming K, et al. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Ottawa(ON): 2017. Canadian youth perceptions on cannabis [Internet] Available from: http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/CCSA-Canadian-Youth-Perceptions-on-Cannabis-Report-2017-en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Thunderbird Partnership Foundation. Bothwell(ON): 2017. Legalized canna¬bis: the pros and cons for Indigenous communities [Internet] Available from: https://thunderbirdpf.org/legalizing-cannabis/ [Google Scholar]