Abstract

Background

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a directive patient‐centred style of counselling, designed to help people to explore and resolve ambivalence about behaviour change. It was developed as a treatment for alcohol abuse, but may help people to a make a successful attempt to stop smoking.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy of MI for smoking cessation compared with no treatment, in addition to another form of smoking cessation treatment, and compared with other types of smoking cessation treatment. We also investigated whether more intensive MI is more effective than less intensive MI for smoking cessation.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register for studies using the term motivat* NEAR2 (interview* OR enhanc* OR session* OR counsel* OR practi* OR behav*) in the title or abstract, or motivation* as a keyword. We also searched trial registries to identify unpublished studies. Date of the most recent search: August 2018.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials in which MI or its variants were offered to smokers to assist smoking cessation. We excluded trials that did not assess cessation as an outcome, with follow‐up less than six months, and with additional non‐MI intervention components not matched between arms. We excluded trials in pregnant women as these are covered elsewhere.

Data collection and analysis

We followed standard Cochrane methods. Smoking cessation was measured after at least six months, using the most rigorous definition available, on an intention‐to‐treat basis. We calculated risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for smoking cessation for each study, where possible. We grouped eligible studies according to the type of comparison. We carried out meta‐analyses where appropriate, using Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects models. We extracted data on mental health outcomes and quality of life and summarised these narratively.

Main results

We identified 37 eligible studies involving over 15,000 participants who smoked tobacco. The majority of studies recruited participants with particular characteristics, often from groups of people who are less likely to seek support to stop smoking than the general population. Although a few studies recruited participants who intended to stop smoking soon or had no intentions to quit, most recruited a population without regard to their intention to quit. MI was conducted in one to 12 sessions, with the total duration of MI ranging from five to 315 minutes across studies. We judged four of the 37 studies to be at low risk of bias, and 11 to be at high risk, but restricting the analysis only to those studies at low or unclear risk did not significantly alter results, apart from in one case ‐ our analysis comparing higher to lower intensity MI.

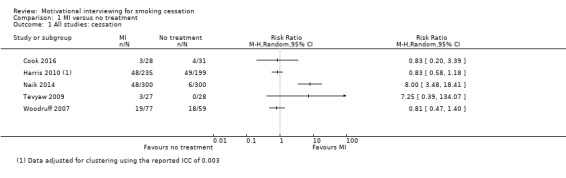

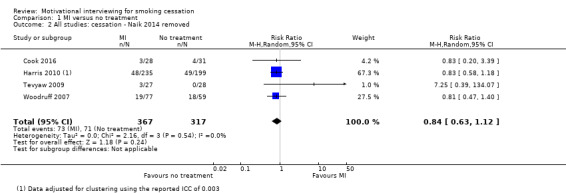

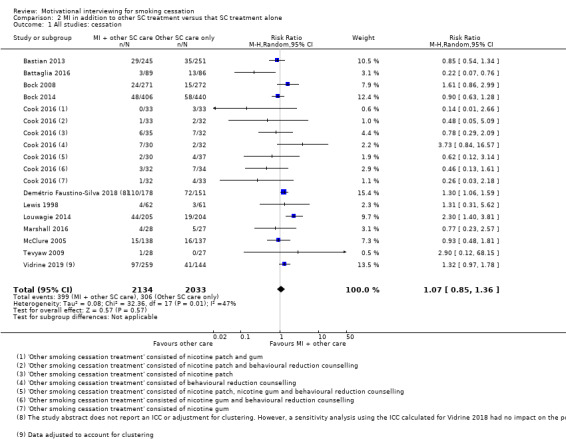

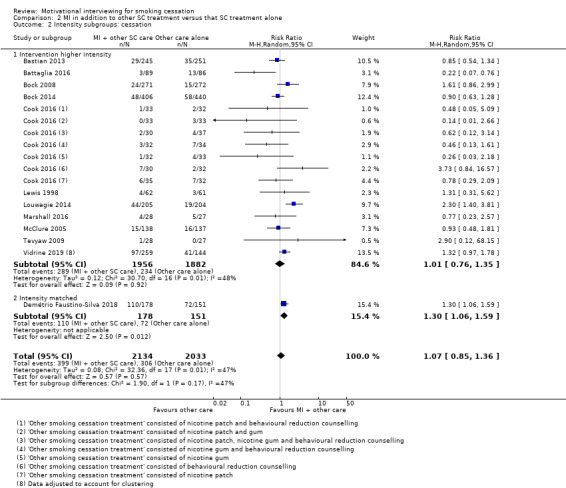

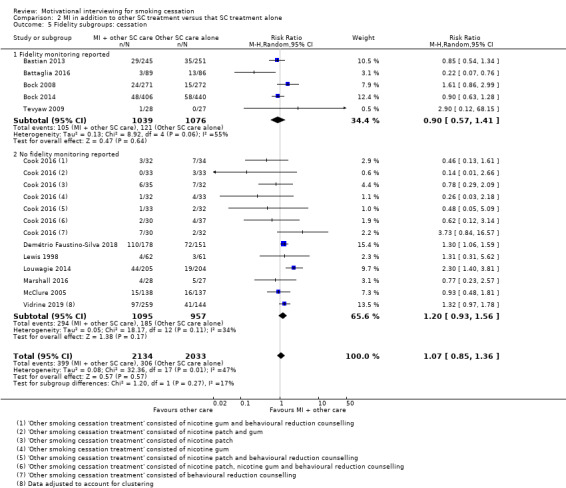

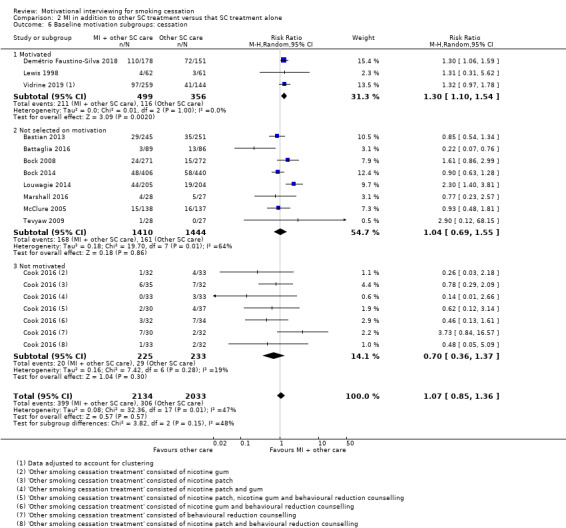

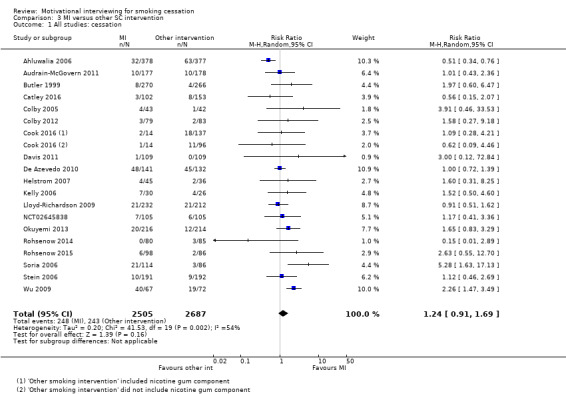

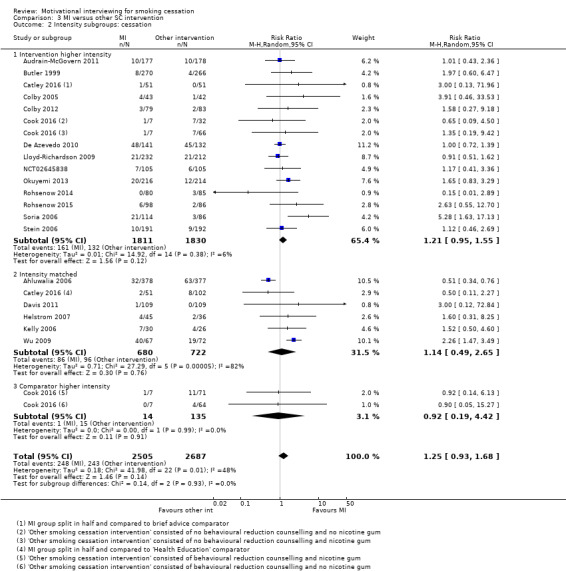

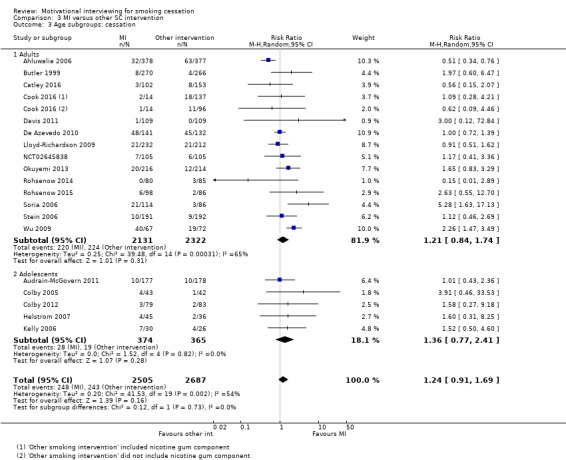

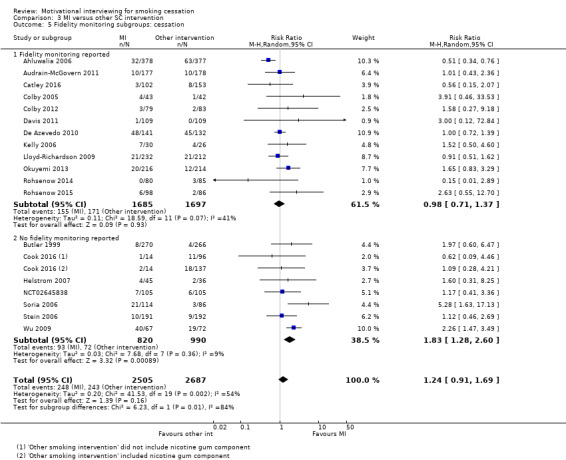

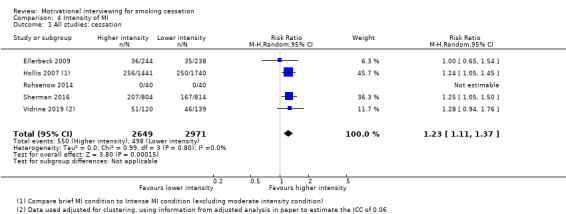

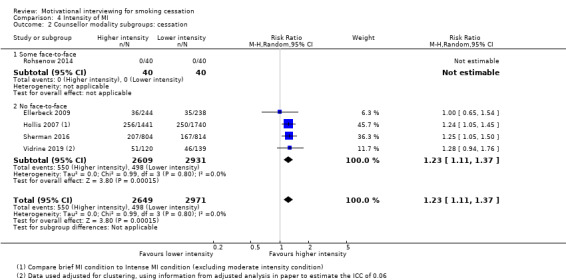

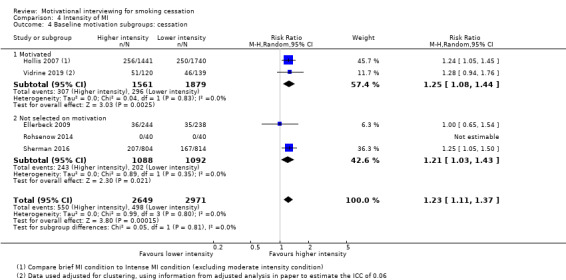

We found low‐certainty evidence, limited by risk of bias and imprecision, comparing the effect of MI to no treatment for smoking cessation (RR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.12; I2 = 0%; adjusted N = 684). One study was excluded from this analysis as the participants recruited (incarcerated men) were not comparable to the other participants included in the analysis, resulting in substantial statistical heterogeneity when all studies were pooled (I2 = 87%). Enhancing existing smoking cessation support with additional MI, compared with existing support alone, gave an RR of 1.07 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.36; adjusted N = 4167; I2 = 47%), and MI compared with other forms of smoking cessation support gave an RR of 1.24 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.69; I2 = 54%; N = 5192). We judged both of these estimates to be of low certainty due to heterogeneity and imprecision. Low‐certainty evidence detected a benefit of higher intensity MI when compared with lower intensity MI (RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.37; adjusted N = 5620; I2 = 0%). The evidence was limited because three of the five studies in this comparison were at risk of bias. Excluding them gave an RR of 1.00 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.54; I2 = n/a; N = 482), changing the interpretation of the results.

Mental health and quality of life outcomes were reported in only one study, providing little evidence on whether MI improves mental well‐being.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to show whether or not MI helps people to stop smoking compared with no intervention, as an addition to other types of behavioural support for smoking cessation, or compared with other types of behavioural support for smoking cessation. It is also unclear whether more intensive MI is more effective than less intensive MI. All estimates of treatment effect were of low certainty because of concerns about bias in the trials, imprecision and inconsistency. Consequently, future trials are likely to change these conclusions. There is almost no evidence on whether MI for smoking cessation improves mental well‐being.

Plain language summary

Does motivational interviewing help people to quit smoking?

Background

Motivational interviewing is a type of counselling that can be used to help people to stop smoking. It aims to help people explore the reasons that they may feel unsure about quitting and find ways to make them feel more willing and able to stop smoking. Rather than telling the person why and how they should change their behaviour, counsellors try to help people to choose to change their own behaviour, increasing their confidence that they can succeed. This review explores whether motivational interviewing helps more people to stop smoking than no treatment, or other types of stop smoking treatment. It also looks at whether longer motivational interviewing, with more counselling sessions, helps more people to quit than shorter motivational interviewing with fewer sessions.

Study characteristics

This review included 37 trials covering over 15,000 people who smoked tobacco. Studies were conducted in a lot of different types of people, including people with health problems or drug use problems, young people, homeless people, and people who had been arrested or were in prison. Some people felt ready to quit smoking and others did not. Motivational interviewing was provided in one to 12 sessions and took from as little as five minutes, to as much as eight hours, to deliver. Studies lasted for at least six months. The evidence is up to date to August 2018.

Key results

There was not enough information available to decide whether motivational interviewing helped more people to stop smoking than no stop smoking treatment. People were slightly more likely to stop smoking if they were provided with motivational interviewing rather than another type of treatment to stop smoking, but our findings suggest that there is still a chance that motivational interviewing could also reduce a person's chances of quitting compared with other stop smoking treatments. This means more research is needed to decide whether motivational interviewing can help more people to quit than other types of treatment. Using longer motivational interviewing with more treatment sessions may help more people to give up smoking than shorter motivational interviewing with fewer sessions, however more research is needed to be sure that this is the case.

We also looked at whether being provided with motivational interviewing to quit smoking increased people's well‐being. Most studies did not provide any information about this, and so more studies are needed to answer this question.

Quality of the evidence

There is low‐quality evidence looking at whether motivational interviewing helps more people to quit smoking than no treatment. This means it is difficult to know whether motivational interviewing helps people to quit smoking or not, and more studies are needed. The quality of the evidence was also low for all of the other questions we asked about quitting smoking, which means that our findings may change when new research is carried out. The quality of the research is rated as low because there were problems with the design of studies, findings of studies were very different to one another, and there were not enough data, making it difficult to determine whether motivational interviewing or more intense motivational interviewing helped people to quit smoking or not.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Tobacco use is one of the leading causes of preventable illness and death worldwide, accounting for over seven million deaths annually (GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators 2016). Extrapolation based on current smoking trends suggests that, without widespread quitting, approximately 400 million tobacco‐related deaths will occur between 2010 and 2050, mostly among current smokers (Jha 2011). Most smokers would like to stop (CDC 2017); however, quitting is difficult.

Description of the intervention

The concept of motivational interviewing (MI) evolved from experiences in treating alcohol abuse, and was first described by Miller in 1983. It is defined as "a directive, client‐centred counselling style for eliciting behaviour change by helping clients to explore and resolve ambivalence" (Miller 1983). The four guiding principles: (a) expressing empathy, (b) developing discrepancy, (c) rolling with resistance, (d) supporting self efficacy, have been detailed elsewhere (Miller 2002).

The MI process is a brief psychotherapeutic intervention intended to increase the likelihood that a person will make an attempt to change their harmful behaviour. Adaptations of MI have ranged from brief 20‐minute office interventions (motivational consulting) to Motivation Enhancement Therapy (MET), a multi‐session course of treatment, including a lengthy assessment, personalised feedback and follow‐up interviews (Lawendowski 1998; Rollnick 1992). MI has also been provided by telephone consultations and in a group format. MI and its various forms have been applied both as a stand‐alone intervention or with other treatments, and in a range of settings. These include health settings such as general hospital wards, emergency departments, and general medical practice (Britt 2002).

How the intervention might work

Miller 1994 suggests that motivation may fluctuate over time or from one situation to another, and can be influenced to change in a particular direction. Thus, lack of motivation (or resistance to change) is seen as something fluid, that is open to change. Therefore, the main focus of MI is facilitating behaviour change using a directive approach, by helping people to explore and resolve any ambivalence they may have toward this change (Rollnick 1995), and in turn making them more likely to choose to change their behaviour in the desired direction. In this case, that behaviour is smoking and so the goal of MI is to increase motivation to quit, making smoking cessation more likely. Rollnick 1995 also suggests that adopting an aggressive or confrontational style is likely to produce negative responses from people (such as arguing), which may be interpreted by the practitioner as denial or resistance. MI guides people to explore and confront their behaviour, instead of telling them what to do.

Why it is important to do this review

MI has been used primarily for the management of health behaviours in those with behavioural disorders, such as alcohol abuse, drug addiction, weight loss, and treatment compliance, as well as for smoking cessation. Systematic reviews have shown some beneficial effects of MI on these behaviours (Cheng 2015; Cowlishaw 2012; Foxcroft 2016; Gates 2016; Heckman 2010; Hettema 2010; Klimas 2018; Mbuagbaw 2012; Morton 2015; Smedslund 2011). However, these effects are minimal or non‐existent at long‐term follow‐up and included studies are generally deemed to be of limited quality, making it difficult to draw clear conclusions. For example, Morton 2015 concluded that the design of many studies ‐ incorporating multi‐component interventions ‐ made it very difficult to isolate the effects of MI. The previous version of this review (Lindson‐Hawley 2015) resulted in a modest but significant increase in quitting smoking when MI was used in comparison to brief advice or usual care. However, this review encountered the same challenges described by Morton 2015 above, pooled studies with a range of different comparator types, and only included studies that reported providing a form of MI fidelity monitoring. This may have biased the inclusion of studies and thus the results. Therefore, inclusion criteria for this version of the review have been revised to reduce bias (although still control for fidelity monitoring), attempt to isolate the effects of MI, and to be mindful of the comparator group when pooling studies, to allow a range of useful comparisons.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy of MI for smoking cessation compared with no treatment, in addition to another form of smoking cessation treatment, and compared with other types of smoking cessation treatment. We also investigated whether more intensive MI is more effective than less intensive MI for smoking cessation.

We explored whether motivational interviewing for smoking cessation could enhance well‐being.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster RCTs.

Types of participants

Tobacco smokers, excluding pregnant women. We excluded trials that only recruited pregnant women, as their particular needs and circumstances warrant them being treated as a separate population. Studies in pregnant women are covered in a separate Cochrane Review (Chamberlain 2017).

Types of interventions

Interventions labelled as either MI or MET, targeted at tobacco smoking cessation. Eligible interventions were based on the principles and practices of MI (e.g. engaging, focussing, evoking, planning, exploring ambivalence, assessment of motivation and confidence to quit, eliciting 'change talk' and supporting self‐efficacy) as described in Miller 2013, and, in the opinion of the review authors, complied with these principles and practices beyond simply referring to the concepts. We included studies testing interventions that claimed to be based on both MI and another theoretical approach to counselling, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). However, we tested the effect of including these studies using sensitivity analysis.

MI is a specific motivational intervention, which has been incorrectly linked to other interventions or theories, such as the transtheoretical model of change, the decisional balance technique, and client‐centred counselling (Miller 2009). MI is conceptually and practically distinct from these interventions and principles. Therefore, we did not include trials that primarily tested these distinct approaches. Stage‐based interventions, such as the transtheoretical model for smoking cessation, are covered in a separate Cochrane Review (Cahill 2010).

We included studies where the intervention arm included MI as part of a multi‐component intervention (that may or may not have included pharmacotherapy), provided that the additional elements were also included in the control arm, and thus were not being tested. No exclusions were made based on the modality of the intervention.

Eligible studies included a comparison (control) intervention of either 1) no smoking cessation treatment, 2) another smoking cessation intervention, of any length or intensity (including usual care), or 3) another type of MI intervention (e.g. MI of a lower intensity).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Our primary outcome was smoking cessation. We preferred continuous/prolonged cessation over point prevalence cessation, and biochemically validated over self‐reported cessation, where multiple measures were available in included studies. We reported cessation at the longest follow‐up, and excluded trials that did not include data on smoking cessation rates at least six months after baseline.

Secondary outcomes

MI has been linked to self‐determination theory. Markland 2005 proposed that MI can provide the circumstances under which people can initiate and action their own behaviour through 'self‐determination'. Self‐determination theory hypothesises that this self‐determination can lead to positive consequences, such as enhanced well‐being (Ryan 2000). This suggests that MI may increase well‐being as well as promote behaviour change. Therefore, we attempted to collect data on the following secondary outcomes:

Mental health and well‐being. Any measure of mental health and well‐being as defined by included studies

Quality of life (QOL). Any validated QOL scale reported in included studies. For example, the Quality of Life Scale (QOLS) (Burckhardt 2003); the Euro–Quality of Life Questionnaire (EQ‐5D) (EuroQol Group 1990)

We considered including adverse events as an outcome but decided against this. MI and comparator interventions comprise talk about smoking, which rarely gives rise to strong emotions and attendance for counselling is voluntary. Thus, it is unlikely that people who find such talk distressing will attend MI. As a result, we believe that few or no trials will have assessed adverse events, making assessment impossible.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We conducted a search of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialised Register in August 2018. The search strategy is available in Appendix 1. The Register has been developed from electronic searching of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO, together with handsearching of specialist journals, conference proceedings and reference lists of previous trials and overviews. See the Tobacco Addiction Group's website for full details of how the Register is compiled. At the time of the Register search, results from the following databases were included:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), issue 1, 2018;

MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20180726;

Embase (via OVID) to week 201831;

PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20180723.

We also searched the following online trial registries to identify unpublished studies: ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

Although this review is an update of a previous review, we carried out full searches of the literature, from database inception. This was because inclusion criteria were updated for this version and we wanted to ensure we identified relevant studies that may have been excluded in previous versions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (of AF, JL, NL, TT) independently screened the title and abstract of each record returned for eligibility. Where there was uncertainty, the record was put forward to the next round of screening. We then acquired the full‐text reports of any trials deemed potentially relevant. Two authors (of AF, JL, NL, TT) independently assessed the full texts for inclusion, and any disagreements were referred to a third author.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (of AF, JL, NL, TT) independently extracted the following information about each eligible trial, where available:

Details of study design, including methods of randomisation and recruitment

Location and setting of the trial, e.g. hospital‐based, clinic‐based, community‐based

Participant characteristics, e.g. level of motivation, pre‐existing conditions, demographic descriptors

Intervention provider characteristics: e.g. type of provider and MI training provision

Description of the intervention(s), including the nature, frequency and duration of MI, and any co‐interventions used

Description of comparator(s), including the nature, frequency and duration of MI, and any co‐interventions used

Any procedures followed to ensure MI fidelity, and the results of any monitoring

Primary outcome measures: definition of smoking cessation used for primary outcome, timing of longest follow‐up, any biochemical validation

Secondary outcome measures: whether mental health and QoL were measured, definitions of outcomes (where measured), outcome data (where measured)

Loss to follow‐up

Funding source

Declarations of interest

Extraction was then compared and amalgamated for each study, with disagreements referred to a third author.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We evaluated studies on the basis of randomisation procedure, allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data, and any other bias using standard Cochrane methods (Higgins 2011). We also assessed detection bias based on the outcome measure, according to standard methods of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group. If the outcome was objective (i.e. biochemically validated) and/or if contact was matched between arms, we judged the studies as being at low risk of bias, but if the outcome was self‐reported and the intervention arm received more support than the control arm, we judged differential misreport to be possible and rated these studies as being at high risk of bias. For trials of behavioural interventions (such as those included here), it is deemed inappropriate to assess performance bias, as blinding of participants and personnel is not feasible due to the nature of the intervention.

Two authors (of AF, JL, NL, TT) independently rated each domain as being at high, low or unclear risk of bias, for each study. We resolved any disagreement between authors through discussion with a third author.

Measures of treatment effect

For our primary outcome, we extracted the most stringent definition of smoking cessation for each study (i.e. longest follow‐up, continuous/prolonged versus point prevalence, and biochemically validated versus self‐report). Where appropriate, we expressed trial effects as a risk ratio (RR), calculated as: (quitters in treatment group/total randomised to treatment group)/(quitters in control group/total randomised to control group), alongside 95% confidence intervals (CI). A risk ratio greater than 1 indicates a potentially better outcome in the intervention group than in the control group.

Secondary outcomes (mental health and QoL) were discussed narratively.

Unit of analysis issues

We included both individually and cluster‐randomised trials. For cluster RCTs, we considered whether authors had accounted for clustering in their reported analyses. Where possible and appropriate, we adjusted for clustering using the trial's reported intra‐class correlation (ICC), calculated an ICC from the information provided, or applied the reported ICC from a similar trial.

Dealing with missing data

We conducted our analyses on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. using all participants randomised to their original groups as denominators where data were available, and assuming that those lost to follow‐up were continuing to smoke. We extracted numbers lost to follow‐up from study reports and used these to assess the risk of attrition bias. Where any required primary outcome data were not available in study reports, we contacted the authors in an attempt to obtain these.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Before pooling studies, we considered both methodological and clinical variance between studies. Where pooling was deemed appropriate, we investigated statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic (Higgins 2003). This describes the percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance).

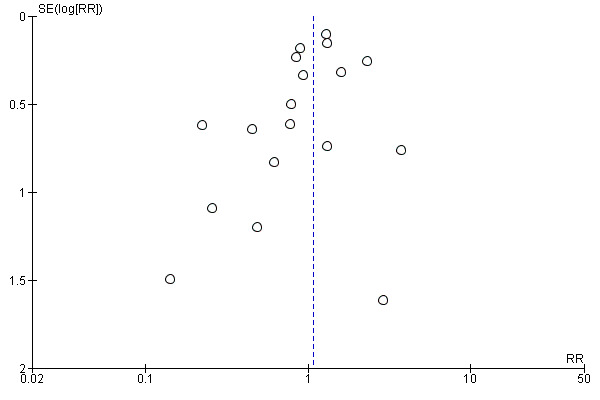

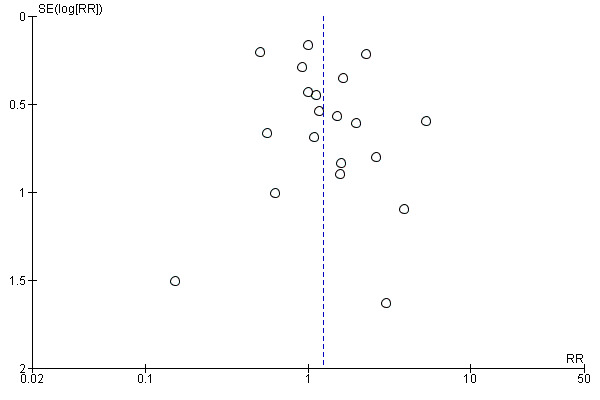

Assessment of reporting biases

We used funnel plots to assess small‐study effects and investigate the possibility of publication bias for the 'MI as an adjunct' and 'MI versus other smoking cessation treatment' comparisons. There were not enough studies (fewer than ten) included in the other analyses to create funnel plots.

Data synthesis

For the primary outcome ‐ smoking cessation ‐ we synthesised groups of studies using Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects models to estimate separate pooled treatment effects (as RRs and 95% CIs), for four types of comparison:

MI versus no smoking cessation intervention (comparison 1)

MI in addition to another smoking cessation treatment versus that smoking cessation treatment alone (comparison 2)

MI alone versus another smoking cessation intervention (comparison 3)

Higher intensity MI versus lower intensity MI (comparison 4)

Secondary outcomes ‐ mental health and QoL ‐ were reported sparsely and so were summarised narratively.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In view of possible heterogeneity between studies, where relevant and there were sufficient studies, we analysed the trials in the following subgroups:

Stratified by whether intensity of smoking cessation support was matched between trial arms, or differed between the MI and comparison group. Intensity was defined as a combination of the number of treatment sessions provided and the overall intervention/comparator contact time.

Stratified by age of participant: adult versus adolescent

Stratified by intervention provider: GP, nurse, counsellor/psychologist, lay healthcare worker

Stratified by counselling modality: face‐to‐face contact (including interventions delivered completely face‐to‐face or partially face‐to‐face) versus no face‐to‐face contact (i.e. via telephone, text messages, virtual reality setting)

Stratified by whether MI fidelity monitoring was reported or not

Stratified by the participants' motivation to quit at baseline, i.e. whether those recruited were motivated to quit, were not motivated to quit, or had not been selected based on their motivation to quit

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out the following sensitivity analyses to see if the pooled results of analyses were sensitive to the removal of:

Studies judged to be at high risk of bias

Studies that measured the fidelity of MI and found that the requirements of MI were not met (fidelity subgroup analyses only)

Studies where the MI intervention was also based on another theoretical approach, such as CBT

'Summary of Findings' table

Following standard Cochrane methodology (Higgins 2011), we created 'Summary of findings' tables for all comparisons:

MI versus no smoking cessation intervention

MI in addition to another smoking cessation treatment versus that smoking cessation treatment alone

MI versus another smoking cessation intervention

Higher intensity MI versus lower intensity MI

We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for the smoking cessation outcome, and to draw conclusions about the certainty of the evidence within the text of the review.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; .

Results of the search

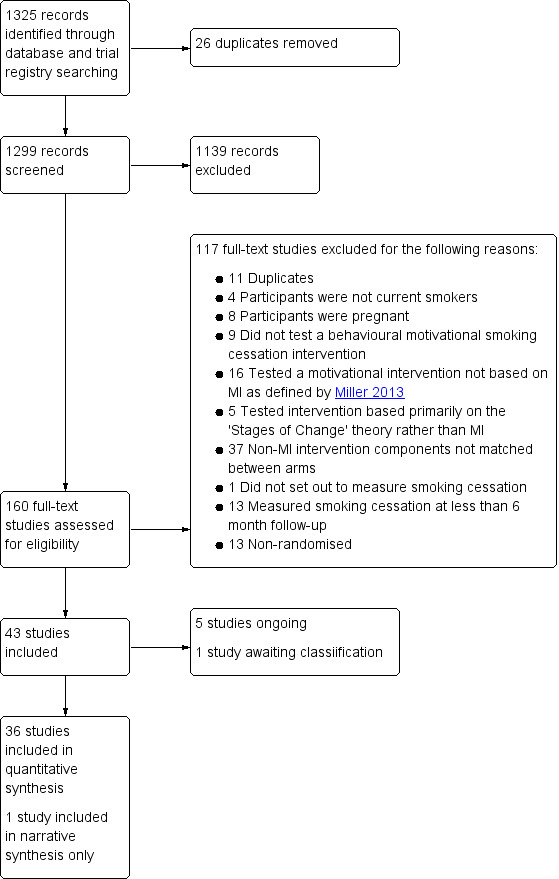

Our searches resulted in 1325 records. After duplicates were removed, 1299 records remained for title and abstract screening. We ruled out 1139 records at this stage, leaving 160 for full‐text screening. We identified 37 completed studies, five ongoing studies, one study awaiting classification, and excluded 117 studies at the full‐text screening stage. See Figure 1 for study flow information relating to the most recent search.

1.

Study flow diagram for this update

Included studies

Included studies

This review includes 37 RCTs, including over 15,000 participants. Trials were conducted in Australia (two studies), Brazil (two studies), the USA (28 studies), China, India, South Africa, Spain and the UK (one study each).

Participants

All participants were tobacco smokers. Eleven of the 37 included studies (Butler 1999; Catley 2016; Cook 2016; Davis 2011; Demétrio Faustino‐Silva 2018; Ellerbeck 2009; Hollis 2007; NCT02645838; Soria 2006; Vidrine 2019; Wu 2009) recruited from the general population, through advertisements, attendance at primary care or other community venues, or through calling a smoking quit‐line. However, the majority of studies in this review recruited from specialist populations:

Adolescents or young people (eight studies; Audrain‐McGovern 2011; Colby 2005; Colby 2012; Harris 2010; Helstrom 2007; Kelly 2006; Tevyaw 2009; Woodruff 2007). One of these studies specifically recruited adolescent offenders (Helstrom 2007). Participants had been arrested or given notice to appear in court for a variety of offences and had been given the option for a diversionary program, but were not incarcerated.

People with substance abuse problems (three studies): Rohsenow 2015 recruited people with a range of substance abuse issues, whereas Rohsenow 2014 specifically recruited people with alcohol dependency and Stein 2006 recruited opoid dependent people receiving methadone treatment.

People attending, or who had attended screening, for smoking‐related cancers (two studies): Marshall 2016 recruited people who were being screened for lung cancer, and McClure 2005 recruited women who had attended for cervical screening, and had been told that they had an elevated risk of cervical cancer.

Patients with a variety of acute health problems (eight studies): In four studies, participants were being treated as hospital inpatients, for unspecified, varied health issues (De Azevedo 2010; Lewis 1998; Sherman 2016) or operative fractures (Matuszewski 2018). In the remaining four studies, patients were attending the emergency department for chest pain (Bock 2008), or receiving outpatient treatment for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Battaglia 2016), HIV (Lloyd‐Richardson 2009), or tuberculosis (Louwagie 2014).

African‐American/black light smokers: defined as smoking ten or fewer cigarettes per day (Ahluwalia 2006)

Incarcerated men in a prison in India (Naik 2014)

Homeless adults recruited from homeless shelters (Okuyemi 2013)

Friends and family of people who had been diagnosed with lung cancer (Bastian 2013)

People with a low income: defined as primary care patients who were uninsured or receiving healthcare benefits (Bock 2014)

The majority of the included studies (29 of 37) did not recruit participants specifically based on their motivation to quit at baseline, i.e. there was not an eligibility criterion that specified that participants needed to be motivated to quit or not; however five studies only recruited participants motivated to quit (Ahluwalia 2006; Demétrio Faustino‐Silva 2018; Hollis 2007; Lewis 1998; Vidrine 2019) and three studies specifically recruited participants who were not motivated to quit (Catley 2016; Cook 2016; Davis 2011). The studies that recruited people motivated to quit had an eligibility criteria specifying that participants had to be willing to quit smoking within a specific time period (e.g. the next two weeks, within a month); recruited people based on their willingness to receive smoking cessation treatment; or recruited people because they had expressed an interest in quitting. The studies that recruited people not motivated to quit advertised for participants who were not ready to quit smoking; had an eligibility criterion specifying that participants should have no interest in quitting over the next month; or participants were not told that the aim of the study was smoking cessation and, when asked about their quitting plans, were excluded if they said they were ready to quit.

Intervention

Motivational Interviewing (MI)

All of the studies included in this review made explicit reference to using MI principles defined by Miller and Rollnick (as described in Miller 2013). Most studies merely specified that the intervention was carried out according to established MI techniques, rather than providing a more detailed description of counselling content. Three studies reported that the counselling in the intervention arm was based on another theoretical approach in addition to MI: Bastian 2013 combined the principles of MI with adaptive coping skills, and both Lewis 1998 and Vidrine 2019 combined MI with principles of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Another study combined the adolescent participant MI intervention with a parent MI intervention in the intervention arm only (Colby 2012). Researchers discussed participants' quit attempts and supporting it with their parents, using MI principles.This study was borderline for inclusion as one of our eligibility criteria was to exclude studies where extra non‐MI components were not matched between study arms. However, we decided to include this study, as the extra component complied with the principles of MI, and we went on to test whether its exclusion impacted upon the results of meta‐analysis using sensitivity analysis.

MI fidelity monitoring

Twenty‐one of the 37 studies reported that they carried out MI fidelity monitoring during the study to assess whether the principles of MI were adhered to, to improve adherence to the principles, or both (Ahluwalia 2006; Audrain‐McGovern 2011; Bastian 2013; Battaglia 2016; Bock 2008; Bock 2014; Catley 2016; Colby 2005; Colby 2012; Davis 2011; De Azevedo 2010; Ellerbeck 2009; Harris 2010; Hollis 2007; Kelly 2006; Lloyd‐Richardson 2009; Okuyemi 2013; Rohsenow 2014; Rohsenow 2015; Sherman 2016; Tevyaw 2009). This usually comprised one or a range of the following methods: the observation of all or a subset of sessions by clinicians or the study lead; rating sessions on their adherence to MI using fidelity scales, such as the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) code (Pierson 2007) or study specific scales; supervision meetings with counselling providers to reflect on practice and learn and improve based on these experiences. Only ten of these 21 studies then went on to report on the results of this fidelity monitoring (Audrain‐McGovern 2011; Catley 2016; Colby 2005; Colby 2012; Davis 2011; Harris 2010; Lloyd‐Richardson 2009; Rohsenow 2014; Rohsenow 2015; Tevyaw 2009). Only one of these studies reported that some of the benchmarks for competency were not widely met (Audrain‐McGovern 2011), and we accounted for this using sensitivity analysis; however, criteria were very close to being met. As fidelity monitoring and benchmarks for fidelity differed across studies, it is plausible that studies that met their own adherence standards may not have met the standards of other studies and vice versa. For further details of fidelity monitoring (where this occurred) see Table 5.

1. Details of MI fidelity monitoring (studies that reported monitoring only).

| Study ID | Details of monitoring | Monitoring results | Fidelity achieved? (defined by individual study parameters) |

| Ahluwalia 2006 | Weekly supervision; subset of sessions rated using MISC | Not reported | n/a |

| Audrain‐McGovern 2011 | Weekly supervision, subset of sessions rated using MITI code | Benchmarks for MI competency (>= 6) approached/achieved for 2 ratings of empathy (mean: 5.2; SD: 0.87) & spirit (mean: 5.9; SD: 0.81) using 7‐point Likert scale. Behavioural counts met benchmarks for proficiency, including ratio of reflections to questions (1.8), percentage of open questions (61%), and MI adherence (96%). 28% of complex reflections approached benchmark for beginning proficiency (40%). | No, in some cases marker did not quite meet the benchmarks set; however were close |

| Bastian 2013 | Each counsellors first 3 sessions monitored & feedback provided; weekly supervision; random sessions rated using MITI code | Not reported | n/a |

| Battaglia 2016 | Random calls observed; nurse participated in ongoing MI training | Not reported | n/a |

| Bock 2008 | Subset of sessions audited using a decisional balance review tool and intervention component checklists | Not reported | n/a |

| Bock 2014 | Subset of sessions reviewed; weekly supervision | Not reported | n/a |

| Catley 2016 | Training continued until counsellors met fidelity criteria for 3 consecutive sessions; subset of sessions rated using MITI code | Mean (SD) global ratings (1–5): Empathy MI = 4.5 (0.6) 95% above criterion, HE = 2.3 (1.2) 24% above criterion, MD = 2.3 (95% CI = 1.8, 2.8). Direction MI = 4.9 (0.4) 97% above criterion, HE = 4.7 (0.8) 95% above criterion, MD = 0.3 (–0.2, 0.8), P = 0.17. Collaboration MI = 4.2 (0.9) 79% above criterion, HE = 2.1 (1.2) 14% above criterion, MD = 2.1 (1.6, 2.5). Evocation MI = 4.4 (0.7) 92% above criterion, HE = 2.3 (1.1) 19% above criterion, MD = 2.2 (1.8, 2.7). Autonomy support MI = 4.3 (0.8) 87% above criterion, HE 2.8 (1.2) 27% above criterion, MD = 1.5 (1.1, 2.0). Giving information (counts): MI = 3.9 (4.8) n/a % above criterion, HE = 12.8 (9.5) n/a % above criterion, MD = 1.2 (95% CI 0.7, 1.7). Reflections: questions (ratio of counts): MI = 3.1 (2.4) 92% above criterion, HE = 0.2 (0.3) 5% above criterion, MD = 1.7 (95% CI 1.2, 2.1). Open‐ended questions (%): MI = 66.0 (27.6) 76% above criterion, HE = 10.5 (11.0) 3% above criterion, MD = 2.6 (95% CI 2.2, 3.1). Complex reflections (%) MI = 53.9 (16.3) 82% above criterion, HE = 19.6 (27.6) 24% above criterion, MD = 1.5 (95% 1.1, 2.0). MI adherent (%) MI = 79.4 (37.9) 71% above criterion, HE = 30.3 (42.6) 22% above criterion, MD = 1.2 (95% CI 0.8, 1.7). MI adherent behaviour counts MI = 2.3 (1.7) n/a % above criterion, HE = 0.8 (1.3) n/a % above criterion, MD = 1.0 (95% 0.5, 1.5). MI non‐adherent behaviour counts MI = 0.2 (0.7) n/a % above criterion, HE = 1.5 (3.0) n/a % above criterion, MD = 0.6 (95% CI 0.1, 1.1) | Yes |

| Colby 2005 | Weekly group supervision; each session rated on scales from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) on rapport, counsellor empathy & self‐efficacy enhancement; delivery of 15 essential elements of the protocol were also rated as 0 (topic not introduced), 1 (not at all useful), 2 (somewhat useful), or 3 (very useful) | Participant ratings high for counsellor rapport (M = 3.8, SD = 0.6), empathy (M = 3.5, SD = 0.8), and self‐efficacy enhancement (M = 3.7, SD = 0.7). Participants recalled 94% of essential elements; interventionists reported discussing 98% of the elements. Utility judged high by participants (M = 2.4, SD = 0.5) and interventionists (M = 2.4, SD = 0.3) | Yes |

| Colby 2012 | Weekly supervision; interventionists & adolescent participants rated sessions | Interventionists & adolescents indicated that nearly all 16 MI session components were delivered (M = 15.6, SD = 0.80 and M = 15.4, SD = 1.39 respectively). Interventionists indicated that they provided 10.7 of 12 (SD = 1.78) parent MI components. | Yes |

| Davis 2011 | Sessions reviewed for protocol adherence and discussed at weekly meetings | Two cases did not meet treatment standard. Cases not reaching criterion were removed from the analyses. | Yes |

| De Azevedo 2010 | Fortnightly supervision | n/a | n/a |

| Ellerbeck 2009 | Each session rated on key concepts of MI and specific content of MI protocol; counsellors rated themselves and were rated during supervision using MI markers. | Not reported | n/a |

| Harris 2010 | Counsellors had to demonstrate proficiency in MI; weekly supervision; supervisors rated counsellors' in‐session proficiency on 18 items, including reflective listening, asking permission, and MI spirit; where fidelity scores dropped, additional supervision was provided until they increased or the counsellor was dismissed | Fidelity scores remained high throughout (mean rating of 6.12 (0.87 SD) on the MI‐spirit item) | Yes |

| Hollis 2007 | Calls monitored and rated on adherence | Not reported | n/a |

| Kelly 2006 | Supervision, including a review of each session to reduce content drift/contamination | Not reported | n/a |

| Lloyd‐Richardson 2009 | Supervision on sample of sessions; participant exit interviews; documentation of time spent in intervention; subset of sessions rated on degree of adherence | Content delivered was appropriate, and exceeded SC arm | Yes |

| Okuyemi 2013 | Sessions reviewed during weekly supervision | Not reported | n/a |

| Rohsenow 2014 | Subset of sessions reviewed in weekly supervision, rated for MI style & adherence with feedback given. Rated from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extensively) scale for 5 motivational style measures, and on adequacy of six MI adherence items | Therapist style ratings did not differ across conditions for arguing (on average not at all), but MI therapists showed more empathy, used more reflective listening, supported self‐efficacy more, and emphasised personal responsibility more. MI therapists more likely to discuss topics to increase ambivalence (100% of MI, 4% of BA sessions), provide assessment feedback (100% of MI, 0% of BA sessions), explore barriers (82.1% of MI, 0% of BA sessions), provide summaries (100% of MI, 0% of BA sessions), and discuss possible goals (100% of MI, 14.8% of BA sessions) | Yes |

| Rohsenow 2015 | Subset of sessions reviewed in weekly supervision, rated for MI style & adherence & feedback given. Rated from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extensively) scale for 5 motivational style measures, and on adequacy of six MI adherence items | MI more likely to discuss: ambivalence about smoking (93% of MI, 4% of BA sessions), assessment feedback (100% of MI, 0% of BA sessions), barriers to quitting smoking (100% of MI, 17% of BA sessions), provide summaries (100% of MI, 0% of BA sessions), methods of quitting or preparing to quit (100% of MI, 58% of BA sessions), and possible goals (100% of MI, 14.8% of BA sessions). Therapist style ratings did not differ between conditions for arguing, empathy, or reflective listening, but MI therapists more likely to support self‐efficacy & emphasise personal responsibility. | Yes |

| Sherman 2016 | Subset of calls reviewed & feedback given on MI techniques; weekly supervision | Not reported | n/a |

| Tevyaw 2009 | Participants & counsellors rated which of 15 MET elements and 4 REL elements were completed | Therapists reported covering 14.9 (SD = 0.4) of 15 MET components and 0 (SD = 0.1) of 4 REL components during MET; and all 4 (SD = 0) of the REL components and 0.7 (SD = 0.5) of the MET components during REL. Student ratings reported that therapists covered 14.3 (SD = 1.3) of 15 MET components & 1.6 (SD = 1.5) of 4 REL components during MET sessions. They reported therapists covered 3.3 ( SD = 1.1) of the 4 REL components and 6.3 (SD = 5.3) of the 15 MET components during REL sessions. | Yes |

BA:brief advice HE: Health Education M: mean MD: mean difference MET: Motivational Enhancement Therapy MISC: Motivational Interviewing Skills Code MI: Motivational Interviewing MITI: Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity n/a: not applicable REL: muscle relaxation training SC: smoking cessation SD: standard deviation

Pharmacotherapy

Twenty of the 37 studies offered or recommended the use of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation to all, or a subset of participants, in the study groups of interest for this review. This was typically nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) only (Ahluwalia 2006; Bastian 2013; Bock 2008; Bock 2014; Cook 2016; Hollis 2007; Lloyd‐Richardson 2009; Okuyemi 2013; Rohsenow 2014; Rohsenow 2015; Sherman 2016; Stein 2006; Vidrine 2019; Wu 2009), however one study offered bupropion only (Soria 2006), and some studies provided a choice of pharmacotherapies from two or all three of the following: NRT, varenicline or bupropion (Battaglia 2016; Catley 2016; Ellerbeck 2009; Harris 2010; McClure 2005). In all cases, pharmacotherapy was offered or recommended in all relevant trial arms, and so the use and type of pharmacotherapy was not being tested. Where included studies did have trial arms testing additional components to MI, these study arms were not included in analyses (Ellerbeck 2009; Lewis 1998).

Modality

MI was delivered in face‐to‐face sessions in 17 of the 37 studies; in another 12 studies, the counselling was delivered in a combination of face‐to‐face and telephone sessions, usually with an initial session or sessions conducted face‐to‐face, followed by follow‐up counselling over the phone. Six studies provided counselling over the phone only (Bastian 2013; Battaglia 2016; Ellerbeck 2009; Hollis 2007; McClure 2005; Sherman 2016); a further study had an MI intervention group that received calls and text messages based on CBT and MI and another MI group that received text messages only (Vidrine 2019), and a final study provided MI counselling for adolescents in an online virtual environment (Woodruff 2007). Participants were represented by an avatar in the online world and received MI group counselling with other participants and a counsellor within a virtual shopping mall.

Intensity

Nine studies provided a single session of MI in at least one of the MI intervention groups (Butler 1999; Davis 2011; Helstrom 2007; Kelly 2006; Louwagie 2014; Marshall 2016; Matuszewski 2018; Rohsenow 2014; Vidrine 2019); the number of sessions offered ranged from one to 12 across studies. Some studies had more than one MI intervention group of different intensities (Ellerbeck 2009; Hollis 2007; Matuszewski 2018; Rohsenow 2014; Sherman 2016; Vidrine 2019). These studies compared a lower intensity MI intervention comprised of one to two sessions to a higher intensity MI intervention which ranged from two to 11 sessions. The total duration of MI interventions varied greatly across studies, from five minutes to 315 minutes; however length of sessions was not reported in a minority of cases. For further detail on the content and intensity of interventions, see Table 6.

2. Details of intervention & comparator content & intensity.

| Study ID | MI intervention description | Intervention intensity (no. of sessions; total duration) | Non‐MI comparator description | Comparator intensity | Intensity matched? | Pharmacotherapy used? | Other common intervention components |

| Ahluwalia 2006 | MI counselling using semi‐structured script | 6 sessions; 2 h | SC counselling providing information & advice to develop a quit plan | 6 sessions; 2 h | Yes | NRT in half each condition; placebo NRT in other half | Tailored smoking cessation booklet |

| Audrain‐McGovern 2011 | MET counselling | 5 sessions; 3 h 15 min | Structured brief advice, using '5As' or '5Rs' | 5 sessions; 1 h 15 min | No, comparator lower | n/a | n/a |

| Bastian 2013 | MI & adaptive coping skills counselling + self‐directed materials. Skills training informed by Transactional Model of Stress & Coping | 6 sessions; 3 h | Self‐help materials ‐ letter from oncologist encouraging quitting, quit kit (including SC guide), individually tailored booklet | n/a | No, comparator lower | NRT | Self‐help materials |

| Battaglia 2016 | MI counselling + written SC information | 12 sessions; 3 h 20 min | PTSD home telehealth programme + electronic (Health Buddy) device | n/a | No, comparator lower | NRT, bupropion or varenicline | PTSD home telehealth programme + electronic (Health Buddy) device |

| Bock 2008 | MI counselling + self help resources | 5 sessions; 1 h 20 min | Non‐MI counselling calls + self‐help resources | 2 sessions; 20 min | No, comparator lower | NRT | 2 brief non‐MI counselling calls, review of NRT use instructions |

| Bock 2014 | MI counselling + 5As intervention | 3 sessions; approx 1 h | 5As intervention | 1 session; 5 min | No, comparator lower | NRT | 5As intervention |

| Butler 1999 | Brief MI session | 1 session; 10 min | Brief SC advice | 1 session; 2 min | No, comparator lower | n/a | n/a |

| Catley 2016 | MI counselling | 4 sessions; length unclear | 1. brief advice 2. SC counselling based on clinical guidelines |

1. 1 session 2. 4 sessions (lengths unclear) | Yes (health education intensity matched) & No (brief advice ‐ lower) | NRT or varenicline | Self‐help guide |

| Colby 2005 | MI counselling | 2 sessions; 50 min | Brief recommendation to quit + follow‐up call | 2 sessions; 10 min | No, comparator lower | n/a | SC pamphlet + treatment referrals information |

| Colby 2012 | MI counselling. Participants' parents also discussed child's quit attempt and supporting it with researchers, using MI principles. | 2 sessions for adolescents + 1 for parents; 1 h adolescents; 15 min parents | Brief SC advice with follow‐up session | 2 sessions for adolescents; 10 min (none for parents) | No, comparator lower | n/a | SC pamphlet + treatment referrals information |

| Cook 2016 | MI counselling | 4 sessions; 50 min | 1. Behavioural smoking reduction guidance 2. No treatment |

1. 7 sessions; 1 h 20 min. 2. No sessions |

1. No, higher 2. No, lower |

NRT dependent on trial arm (balanced across arms of interest) | n/a |

| Davis 2011 | Mi counselling | 1 session; 15 min | Prescriptive interview regarding smoking ‐ firm & authoritative | 1 session; 15 min | Yes | n/a | n/a |

| De Azevedo 2010 | MI counselling | 8 sessions; 1 h 40 min | Brief SC advice | 1 session; 15 min | No, comparator lower | n/a | n/a |

| Demétrio Faustino‐Silva 2018 | MI taught to SC advisors as additional resource to standard CBT approach used | Average 3 sessions; length unclear | Standard CBT approach advocated by Brazilian Ministry of Health's smoking programme | Average 3 sessions, length unclear | Yes | n/a | CBT counselling approach |

| Ellerbeck 2009 | 1. High intensity MI 2. Moderate intensity MI |

1. 6 sessions every 6 min; length unclear 2. 2 sessions every 6 min; length unclear |

n/a | n/a | n/a | NRT or bupropion | Welcome letter, information about medication, smoking cessation pamphlets, 6‐monthly personalised newsletter, periodic progress reports with counselling suggestions faxed to participants' physicians |

| Harris 2010 | MI counselling | 4 sessions; average 1 h 40 min | MI counselling focused on increasing fruit & vegetable consumption | 4 sessions; average 1 h 40 min | n/a | Pharmacotherapy for highly dependent smokers | n/a |

| Helstrom 2007 | MET counselling | 1 session; length unclear | Information session on tobacco use based on American Cancer Society pamphlet | 1 session; length unclear | Yes | n/a | n/a |

| Hollis 2007 | 1. high intensity MI 2. moderate intensity MI 3. low intensity MI |

1. 5 sessions; at least 1 h 2. 2 sessions; at least 45 min 3. 1 session; 15 min |

n/a | n/a | n/a | NRT for half of participants in each group | “Quit kit” including SC booklet |

| Kelly 2006 | MI counselling | 1 session; 1 h | SC counselling based on psychoeducation model | 1 session; 1 h | Yes | n/a | Written materials |

| Lewis 1998 | Brief motivational message to quit smoking, with follow‐up counselling incorporating CBT & MI | 5 sessions; approx 1 h | Brief motivational message to quit smoking + SC pamphlet | 1 session; 3 min | No, comparator lower | Placebo NRT | Brief motivational message to quit + SC pamphlet |

| Lloyd‐Richardson 2009 | MET counselling | 5 sessions; at least 2 h | Brief assessment of quitting plans with brief in‐person follow‐up | 2 sessions; approx 10 m | No, comparator lower | NRT | n/a |

| Louwagie 2014 | Brief MI session + short standardised SC message + SC booklet | 1 session; 15‐20 min | Short standardised SC message + SC booklet | 1 session; 1 min | No, comparator lower | n/a | Short SC message + SC booklet |

| Marshall 2016 | MI counselling session + audio quit material + printed materials + quit‐line details | 1 session; approx 25 min | Non‐tailored printed materials + quit‐line details | n/a | No, comparator lower | n/a | Written materials + quit‐line details |

| Matuszewski 2018 | 1. MI counselling + control intervention 2. MI counselling intervention + additional brief follow‐up |

1. 1 session; average 10 min 2. 2 sessions; average 15 min |

Referral to patient resource centre + quit‐line brochure | n/a | No, comparator lower | n/a | Referral to patient resource centre + quit‐line brochure |

| McClure 2005 | MET counselling + control intervention | 4 sessions; 1 h | Letter explaining association between cervical cancer & smoking + SC booklet + quit‐line details | n/a | No, comparator lower | NRT or bupropion | Letter explaining association between cervical cancer & smoking, SC booklet, quit‐line details |

| Naik 2014 | MI counselling | not reported | No intervention (waiting list control) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| NCT02645838 | MI counselling | 7 sessions; unclear‐ over 20 min | Brief SC advice | 1 session; 5 min | No, comparator lower | n/a | n/a |

| Okuyemi 2013 | MI SC and NRT adherence counselling | 6 sessions; average 1h 45 min | Brief smoking cessation advice + SC guide | 1 session; 10‐15 min | No, control lower | NRT | SC guide |

| Rohsenow 2014 | 1. MI counselling session 2. MI counselling session + booster sessions |

1. 1 session; 45 min 2. 3 sessions 1h 5min |

1. Brief advice using US AHRQ method 2. Brief advice + 2 booster sessions |

1. 1 session; 15 min 2. 3 sessions; 35 min |

No, comparator lower | NRT | SC pamphlets, information on SC skills groups & hard candy |

| Rohsenow 2015 | MI session + booster sessions (half received non contingent payments & half contingent payments) | 4 sessions; approx 2 h | Brief advice using US AHRQ methods (half received non contingent payments & half contingent payments) | 4 sessions; approx 55 min | No, comparator lower | NRT | SC pamphlets & hard candy |

| Sherman 2016 | 1. MI & Problem Solving Therapy counselling 2. Referral to state Quitline (usually New York state) ‐ counsellors trained in MI |

1. 7 sessions; approx 1 h 30 min 2. 2 sessions; approx 30 min |

n/a | n/a | n/a | NRT | n/a |

| Soria 2006 | MI counselling | 3 sessions; 60 min | Brief anti‐smoking advice | 1 session; 3 min | No, comparator lower | Bupropion for highly dependent smokers | n/a |

| Stein 2006 | MI counselling | 3 sessions; approx 1h | Brief advice using 4As + self‐help materials | 2 sessions; approx 5 min | No, comparator lower | NRT | n/a |

| Tevyaw 2009 | MET (half received non contingent payments & half contingent payments) | 3 sessions; 2 h | Progressive muscle relaxation training (half received non contingent payments & half contingent payments) | 3 sessions; 2 h | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Vidrine 2019 | 1. Brief advice + text messages based on CBT & MI 2. Brief advice + texts + counselling calls based on CBT & MI |

1. 1 session; approx 5 min. 2. 11 sessions; approx 2 h |

Brief SC advice | 1 session; approx 5 min | No, comparator lower | NRT | Brief quitting advice, written materials, quit‐line details |

| Woodruff 2007 | Online virtual world (The Breathing Room) ‐ participants' avatars had MI group counselling with other participants & the counsellor within a virtual shopping mall setting | 7 sessions; 5 h 15 min | No treatment | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Wu 2009 | MI counselling + SC self‐help materials | 4 sessions; 4 h | Health education counselling + self‐help materials covering nutrition, exercise, and tobacco use | 4 sessions; 4 h | Yes | NRT | n/a |

5As: 'Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange'

5Rs: 'Relevance, Risks, Rewards, Roadblocks, Repetition' AHRQ: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality approx: approximately CBT: Cognitive Behavioural Therapy h: hour(s)

m: month(s) min: minute(s) MI: Motivational interviewing MET: Motivational Enhancement Therapy n/a: not applicable NRT:nicotine replacement therapy PTSD: post traumatic stress disorder SC: smoking cessation

Provider

MI was delivered by physicians (Butler 1999; Marshall 2016; NCT02645838; Soria 2006), nurses (Battaglia 2016; Davis 2011; Lewis 1998), counsellors/psychologists (Ahluwalia 2006; Audrain‐McGovern 2011; Bastian 2013; Bock 2008; Bock 2014; Catley 2016; Colby 2005; Colby 2012; Cook 2016; Ellerbeck 2009; Harris 2010; Kelly 2006; Lloyd‐Richardson 2009; McClure 2005; Okuyemi 2013; Rohsenow 2014; Rohsenow 2015; Sherman 2016; Stein 2006; Tevyaw 2009; Vidrine 2019; Woodruff 2007; Wu 2009), some of whom were described as specialist smoking cessation advisors (De Azevedo 2010; Demétrio Faustino‐Silva 2018; Hollis 2007; Matuszewski 2018), and lay healthcare workers (Louwagie 2014). Helstrom 2007 and Naik 2014 did not specify the type of provider delivering support.

Comparator

We grouped studies dependent on the nature of the relevant comparator. Comparators either consisted of no smoking cessation interventions (Cook 2016; Harris 2010; Naik 2014; Tevyaw 2009; Woodruff 2007), a non‐MI smoking cessation intervention (Ahluwalia 2006; Audrain‐McGovern 2011; Bastian 2013; Battaglia 2016; Bock 2008; Bock 2014; Butler 1999; Catley 2016; Colby 2005; Colby 2012; Cook 2016; Davis 2011; De Azevedo 2010; Demétrio Faustino‐Silva 2018; Helstrom 2007; Kelly 2006; Lewis 1998; Lloyd‐Richardson 2009; Louwagie 2014; Marshall 2016; Matuszewski 2018; McClure 2005; NCT02645838; Okuyemi 2013; Rohsenow 2014; Rohsenow 2015; Soria 2006; Stein 2006; Tevyaw 2009; Vidrine 2019; Wu 2009), or another MI intervention of lower intensity (Ellerbeck 2009; Hollis 2007; Matuszewski 2018; Rohsenow 2014; Sherman 2016; Vidrine 2019). Some studies had multiple study arms and so fell into more than one category. We further split the studies with a non‐MI smoking cessation intervention into two groups ‐ those where the MI interventions stood alone and were directly compared with the other cessation interventions, and those where the intervention groups received the MI interventions in addition to the non‐MI smoking cessation interventions, which were also offered in the comparator groups.

No smoking cessation treatment comparator

Three of the five studies that compared MI to no smoking cessation treatment provided no intervention (Cook 2016; Naik 2014; Woodruff 2007). Participants were simply followed up to assess the outcome. Naik 2014 offered participants in the comparator the opportunity to receive the MI intervention following the initial treatment period. Two of the studies provided participants with a 'dummy' intervention designed to match the intensity of the MI smoking cessation intervention. In Harris 2010, this was MI counselling focussed on increasing participants' fruit and vegetable consumption; both study arms received counselling over four sessions for an average duration of 100 minutes. In Tevyaw 2009, participants in the comparison group received 'progressive muscle relation training' over three sessions for an overall duration of 120 minutes.

Non‐MI smoking cessation intervention comparator

In the minority of cases (7 of 31; Ahluwalia 2006; Catley 2016; Davis 2011; Demétrio Faustino‐Silva 2018; Helstrom 2007; Kelly 2006; Wu 2009), the comparator group (or one of the comparator groups in the study) received smoking cessation counselling that was matched in intensity to the MI counselling in the intervention group. This was either described simply as smoking cessation counselling with information giving or advice, or as a specific approach, i.e. prescriptive interviewing (Davis 2011), CBT (Demétrio Faustino‐Silva 2018), or the psychoeducation model (Kelly 2006). Wu 2009 provided participants in the comparator group with general health education counselling, which covered smoking cessation, as well as nutrition and exercise.

In most cases, the support provided in the comparator group was of lower intensity than the MI intervention arm and consisted of brief advice on cessation, self‐help materials (such as printed materials and contact details for smoking cessation services or quit‐lines), or both. In one study, one of the comparator interventions was more intensive than the MI intervention (Cook 2016). Cook 2016 was a 16‐arm factorial trial where some study arms were provided with a behavioural smoking reduction intervention. This reduction intervention was delivered over seven sessions with a total duration of 80 minutes, whereas the MI intervention was delivered over four sessions with a total duration of 50 minutes.

Two studies offered half of their participants payments contingent on them being abstinent from smoking (Rohsenow 2015; Tevyaw 2009). In both cases, these contingency payments were matched in the intervention arm.

Outcomes

The majority of studies measured cessation at six months follow‐up (25 of 37); however, nine studies measured cessation at 12 months follow‐up (Bastian 2013; Bock 2014; Hollis 2007; Marshall 2016; McClure 2005; Rohsenow 2014; Rohsenow 2015; Soria 2006; Woodruff 2007), and one study each measured cessation at nine months (Battaglia 2016), 11 months (Demétrio Faustino‐Silva 2018) and 24 months (Ellerbeck 2009) follow‐up. It was possible to use biochemically validated (using expired carbon monoxide or urinary/salivary cotinine) cessation rates for 22 of the 37 studies. We were unsure whether the rates reported in Naik 2014 and Demétrio Faustino‐Silva 2018 were biochemically verified. The Naik 2014 study report stated that carbon monoxide was measured; however, it was unclear whether this was used to motivate participants, verify cessation rates, or both.

Only one study measured one of our secondary outcomes ‐ mental health. Battaglia 2016 recruited veterans with PTSD attending Veterans Health Administration (VHA) healthcare clinics and investigated the effect of integrating MI smoking cessation counselling into the standard telehealth programme already provided (which included access to pharmacological and behavioural smoking cessation treatments). Throughout the study, PTSD symptoms were assessed using the PTSD Checklist (range of 17 to 85 with a score > 50, indicating PTSD diagnosis), depression was monitored using the 15‐item Geriatric Depression Scale‐Short Form (GDS‐SF), where a score greater than 6 indicated probable depression, and suicidal thoughts were assessed every 30 sessions via a single question. Some of the other studies measured markers of mental health or well‐being at baseline or reported mental health at follow‐up overall; however, only Battaglia 2016 measured mental health at follow‐up and presented the results by study group.

Excluded studies

We listed 117 studies that were potentially relevant but excluded, with reasons, in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Reasons that studies were excluded at full‐text stage are also summarised in Figure 1. The reason why most studies were excluded at full‐text screening stage was because the intervention group received non‐MI intervention components that were not included in the comparator arm, such as pharmacotherapy, a text messaging intervention, or incentives.

We also classified five studies as ongoing (Lloyd‐Richardson 2003; NCT01387516; NCT02905656; NCT03002883; Salgado Garcia 2018), which are likely to be relevant for inclusion once completed and/or reported. We classified Zhou 2014 as 'awaiting classification' as only a conference abstract was available and it was impossible to determine from this whether smoking cessation was definitely measured (reduction in cigarette consumption was reported) and at what time points. Attempts to contact the authors were unsuccessful.

Risk of bias in included studies

Full details of 'Risk of bias' assessments are given for each trial within the Characteristics of included studies tables. Overall, we judged four studies to be at low risk of bias (low risk of bias across all domains), 11 at high risk of bias (high risk of bias in at least one domain), and the remaining 22 at unclear risk of bias. A summary illustration of the 'Risk of bias' profile across trials is shown in Figure 2.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

We assessed selection bias through investigating methods of random sequence generation and allocation concealment for each study. We rated 15 studies as having low risk for random sequence generation, and the remaining 22 as having unclear risk. We judged nine studies to be at low risk for allocation concealment, 27 at unclear risk, and one study at high risk (Woodruff 2007). Woodruff 2007 was judged as having high risk as clusters were randomised to treatments, and study personnel knew which condition a cluster was in before participant recruitment began. Recruitment was then tailored to this, using different recruitment materials dependent on assigned condition. This meant that participants may not have been equivalent across groups. We judged studies as having unclear risk of bias when authors provided insufficient information about methods used.

Outcome assessment (detection bias)

We did not formally assign a risk of performance bias for each trial. It is almost always impossible to blind providers of behavioural support to treatment allocation. Moreover, nonspecific effects of being in treatment are part of the intervention effect that studies were aiming to assess.

We judged detection bias on the basis of biochemical validation and, where biochemical validation was not provided, on the basis of differential levels of contact between participants and the study team across relevant study groups. We judged ten studies to be at high risk of detection bias as outcomes were defined as self‐report only and the intervention and control arms received different levels of support, making differential misreporting possible (Bastian 2013; Bock 2008; Cook 2016; De Azevedo 2010; Hollis 2007; Kelly 2006; Marshall 2016; Sherman 2016; Vidrine 2019; Woodruff 2007). We judged two studies to be at unclear risk of detection bias (Demétrio Faustino‐Silva 2018; Naik 2014) as we were unsure whether the rates reported were biochemically verified. We judged the remaining 25 studies to be at low risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged studies to be at a low risk of attrition bias where the numbers of participants lost to follow‐up were clearly reported, the overall number lost to follow‐up was not more than 50%, and the difference in loss to follow‐up between groups was no greater than 20%. This is in accordance with 'Risk of bias' guidance produced by the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group for assessing smoking cessation studies. We judged 29 of the studies to be at low risk of bias, six at unclear risk (Lewis 1998; Matuszewski 2018; McClure 2005; Naik 2014; Stein 2006; Woodruff 2007) and two at high risk (Bastian 2013; Bock 2014). These two studies were judged to be at high risk because overall loss to follow‐up was more than 50%. Judgements of unclear risk were made either because information on follow‐up was not reported in the sources available to us (Lewis 1998; Matuszewski 2018; McClure 2005; Naik 2014), or because loss to follow‐up was reported for the relevant time point overall, but not split by study group (Stein 2006; Woodruff 2007).

Other potential sources of bias

Two sources of other bias were identified for two of the included studies (Cook 2016; Naik 2014). The comparator intervention in Naik 2014 was a 'waiting list' to receive the MI intervention treatment following the intervention group (verified through contact with author); however, it was unclear whether participants knew that they were on a waiting list. We contacted the authors a second time to verify whether the intervention was delivered to the comparator group after the six‐month assessment time point and received no further reply. However, the quit rates were much higher in the intervention group than in the comparator group (48/300 and 6/300, respectively), suggesting that this was the case. Due to this uncertainty, we have assigned this study a rating of unclear risk for 'other potential sources of bias'. Cook 2016 was a factorial trial with four factors: 1) MI/no MI; behavioural reduction counselling/no behavioural reduction counselling; nicotine gum/no nicotine gum; and nicotine patch/no nicotine patch. The authors reported an unexpected interaction between MI and nicotine gum, where the combination of the two resulted in lower quit rates than any other interventions or combinations. As a result, we have assigned Cook 2016 a rating of high risk of other bias. For details of how data from Cook 2016 have been entered into meta‐analyses, see the Characteristics of included studies table.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Motivational interviewing compared with no treatment for smoking cessation.

| Motivational interviewing compared with no treatment for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: tobacco smokers (adolescents, university students, adult primary care patients) Setting: high schools, university & primary care (USA) Intervention: motivational interviewing Comparison: no smoking cessation treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no treatment | Risk with MI | |||||

| Smoking cessation at ≥ 6 months follow‐up | Study population | RR 0.84 (0.63 to 1.12) | adjusted N = 684 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 | One eligible study (Naik 2014) has been excluded from this pooled analysis as it recruited a substantially different population (incarcerated men) compared with the other studies, which recruited adults and adolescents from the general population. When included in the analysis, it resulted in substantial heterogeneity ‐ removal of Naik 2014 decreased statistical heterogeneity to zero. | |

| 22 per 100 | 19 per 100 (14 to 25) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level as all studies were at high or unclear risk of bias; removing the studies at high risk changed the direction of the effect estimate so that it favoured MI, however the CIs still spanned one and suffered substantial imprecision

2 Downgraded one level due to imprecision: the upper and lower limits of the confidence intervals included both meaningful benefit and harm, and the overall number of events was low (n = 144)

Summary of findings 2. Motivational interviewing in addition to other smoking cessation treatment for smoking cessation.

| Motivational interviewing in addition to other smoking cessation treatment for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: tobacco smokers (general population, low income, inpatients and outpatients with mixed diagnoses) Setting: community, hospital, healthcare clinics (Australia, Brazil, South Africa, USA) Intervention: motivational interviewing in addition to other smoking cessation (SC) treatment Comparison: other smoking cessation treatment alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with other SC treatment only | Risk with MI in addition to other SC treatment | |||||

| Smoking cessation at ≥ 6 months follow‐up | Study population | RR 1.07 (0.85 to 1.36) | adjusted N = 4167 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2, 3 | ||

| 15 per 100 | 16 per 100 (13 to 20) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Five studies judged to be at high risk of bias, however sensitivity analysis suggested this is unlikely to impact on the result ‐ not downgraded

2 Downgraded one level due to inconsistency: study effects differed across studies, demonstrated by moderate unexplained statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 47%)

3 Downgraded one level due to imprecision: the upper and lower limits of the confidence intervals included both meaningful benefit and harm

Summary of findings 3. Motivational interviewing compared with another smoking cessation intervention for smoking cessation.

| Motivational interviewing compared with another smoking cessation intervention for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: tobacco smokers (general population, adolescents, offenders, homeless, substance users, hospital inpatients, HIV‐positive) Setting: community, universities, homeless shelters, inpatient and outpatient healthcare clinics, primary care (Australia, Brazil, China, Spain, UK, USA) Intervention: motivational interviewing Comparison: another SC intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with other SC intervention | Risk with MI | |||||

| Smoking cessation at ≥ 6 months follow‐up | Study population | RR 1.24 (0.91 to 1.69) | 5192 (19 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2, 3 | ||

| 9 per 100 | 11 per 100 (8 to 15) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Three studies judged at high risk of bias, however sensitivity analysis suggested this was unlikely to impact on the result ‐ not downgraded

2 Downgraded one level due to inconsistency: study effects differ across studies, demonstrated by moderate unexplained statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 54%)

3 Downgraded one level due to imprecision: the upper and lower limits of the confidence intervals included both meaningful benefit and harm

Summary of findings 4. Higher compared with lower intensity motivational interviewing for smoking cessation.

| Higher compared with lower intensity motivational interviewing for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: tobacco smokers (general population, hospital inpatients with mixed diagnoses) Setting: community‐based telephone quit‐line, primary care, hospital, inpatient substance abuse treatment centre (USA) Intervention: higher intensity motivational interviewing Comparison: lower intensity motivational interviewing | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with lower intensity MI | Risk with higher intensity MI | |||||

| Smoking cessation at ≥ 6 months follow‐up | Study population | RR 1.23 (1.11 to 1.37) | adjusted N = 5620 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | ||

| 17 per 100 | 21 per 100 (19 to 23) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels due to risk of bias: three of the five studies were judged to be at high risk of bias and removing these studies in a sensitivity analysis changed the interpretation of the effect, so that the confidence intervals encompassed both appreciable benefit and harm of higher intensity motivational interviewing for smoking cessation

MI versus no smoking cessation treatment (comparison 1)

Smoking cessation outcome