Abstract

Various methods, approaches, and strategies designed to understand and reduce health disparities, increase health equity, and promote community and population health have emerged within public health and medicine. One such approach is community-engaged research. While the literature describing the theory, principles, and rationale underlying community engagement is broad, few models or frameworks exist to guide its implementation. We abstracted, analyzed, and interpreted data from existing project documentation including proposal documents, project-specific logic models, research team and partnership meeting notes, and other materials from 24 funded community-engaged research projects conducted over the past 17 years. We developed a 15-step process designed to guide the community-engaged research process. The process includes steps such as: networking and partnership establishment and expansion; building and maintaining trust; identifying health priorities; conducting background research, prioritizing “what to take on”; building consensus, identifying research goals, and developing research questions; developing a conceptual model; formulating a study design; developing an analysis plan; implementing the study; collecting and analyzing data; reviewing and interpreting results; and disseminating and translating findings broadly through multiple channels. Here, we outline and describe each of these steps.

Keywords: community-engaged research, partnership, disparities, equity, process

INTRODUCTION

Various methods, approaches, and strategies designed to understand and reduce health disparities, increase health equity, and promote community and population health have emerged within public health and medicine. One such approach is community-engaged research (Clinical and Translational Science Awards [CTSAs] Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement, 2011; Committee to Review the CTSAs Program at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Institute of Medicine, 2013; Rhodes, 2014; Trinh-Shevrin, Islam, Nadkarni, Park, & Kwon, 2015; Wolfson et al., 2017). Simply defined, community-engaged research is an approach to research designed to improve health through the involvement of the impacted community in research, where the community refers to any group of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations. Rather than researchers from universities, government, or other types of research organizations approaching and entering a community with a preconceived notion of what is best for a community, community-engaged research involves community members and representatives from community organizations collaborating and sharing research roles with academic researchers. Community-engaged research moves from treating community members as targets of research to engaging them as research partners. Community-engaged research emphasizes collaboration and co-learning; reciprocal transfer of expertise; sharing of decision-making power; and shared ownership of the processes and products of research (CTSAs Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement, 2011; Committee to Review the CTSAs Program at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Institute of Medicine, 2013; Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Rhodes, 2014; Trinh-Shevrin et al., 2015).

Community-engaged research is viewed as an approach to reduce the “17-year gap”, which suggests that it takes 17 years for 14 percent of original research to benefit patient care (Balas et al., 2000), because among its strengths, community-engaged research builds bridges among community members, those who serve communities through service delivery and practice, and academic researchers. Incorporating the experiences of community members, who are experts in their lived experiences and their community’s needs, priorities, and assets, and of representatives from community organizations with sound science can promote the reduction of health disparities and achieve health equity through deeper and more informed understandings of health-related phenomena and the identification of actions (e.g., interventions, programs, policies, and system changes) that are more relevant; culturally congruent; and likely to be effective, sustained, and scalable, if warranted (CTSAs Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement, 2011; Committee to Review the CTSAs Program at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Institute of Medicine, 2013; Kost et al., 2016; Rhodes, Mann-Jackson, et al., 2017). Similarly, study designs, including those used to evaluate actions, that are informed by multiple perspectives may be more authentic to the community and to the ways that community members convene, interact, and take action. Thus, interventions, for example, may be more innovative; recruitment benchmarks, including enrollment and retention rates, may be higher; measurement may be more precise; data collection may be more acceptable, complete, and meaningful; analysis and interpretation of findings may be more accurate; and sustainability and meaningful dissemination of findings may be more likely (Rhodes, Alonzo, et al., 2017; Rhodes, Duck, Alonzo, Downs, & Aronson, 2013; Rhodes, Mann-Jackson, et al., 2017). Furthermore, working with rather than merely in communities, partners applying community-engaged research approaches may strengthen a community’s overall capacity to problem-solve through participation in the research process.

Community-engaged research is often viewed across a continuum that spans from outreach, consultation, involvement, collaboration, to shared leadership (CTSAs Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement, 2011; Committee to Review the CTSAs Program at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences & Institute of Medicine, 2013). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a form of community-engaged research in which community members are equal partners sharing leadership with academic researchers throughout the entire research process.

Our community-engaged research partnership has a 17-year history of working collaboratively to reduce health disparities, increase health equity, and promote community and population health. Our research is conducted by a community-university partnership comprised of community members, practitioners, academic researchers, and lay-experts from academic, government, and nongovernment institutions, including community organizations and businesses. We focus on understanding community needs, priorities, and assets, and developing, implementing, and evaluating interventions to reduce the burdens of HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and increase access to health services among Latino and African American/Black communities; gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM); transgender persons; rural populations; immigrants; and persons living with HIV (Rhodes, Mann-Jackson, et al., 2017; Rhodes et al., 2014). Generally, we have followed steps of trust building; fostering collaborative co-learning networks with key stakeholders (e.g., community members, organization representatives, and academic researchers); and iteratively developing, pretesting, implementing, and evaluating interventions (Rhodes, Alonzo, Mann, Freeman, et al., 2015; Rhodes, Alonzo, et al., 2017; Rhodes, Daniel, et al., 2013; Rhodes, Duck, Alonzo, Daniel, & Aronson, 2013; Rhodes, Duck, Alonzo, Downs, et al., 2013; Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2007; Rhodes et al., 2006).

The theory, principles, and rationale underlying community-engaged research are well developed; however, there remains a need for models and frameworks to guide the implementation of community-engaged research in practice (CTSAs Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement, 2011; Committee to Review the CTSAs Program at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Institute of Medicine, 2013). Thus, given the profound gap in the literature of models or frameworks to guide community-engaged research and our partnership’s successes in conducting community-engaged research, we sought to codify our process to provide a stepwise framework for successfully initiating and conducting community-engaged research.

METHODS

Our Community-engaged Research Partnership

Members of our partnership, outlined in Table 1, focus on the health of ethnic/racial, sexual, and gender-identity minorities and economically disadvantaged communities. Partners work on multiple projects and may be involved with and committed to different projects; however, our partnership is not study-specific. Partners may join and leave or may be more or less involved, but the partnership remains despite transitions. Community-engaged research requires an ongoing partnership that ideally is not tied to a single study or funding source; in fact, partners should be committed to, and involved in, the partnership, with or without funding (Rhodes, 2012; Rhodes, Alonzo, et al., 2017; Rhodes, Duck, Alonzo, Daniel, et al., 2013; Rhodes, Mann-Jackson, et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Community-engaged research partnership members

| Community members |

| Representatives from local service and health-focused organizations, e.g., public health departments (local and state levels); other community organizations, including Latino soccer leagues and teams; a lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) pride organization; and Latino-serving organizations; and local foundations |

| Staff at local businesses, including media organizations, Internet companies, bars and clubs, a video production company, and tiendas (Latino grocers) |

| Clinic providers and staff |

| Scientists from US federal agencies |

| Researchers from universities |

To develop the community-engaged research process, we abstracted data from existing project documentation including proposal documents, project-specific logic models, research team and partnership meeting notes, and other materials, e.g., summaries of interventions, progress reports, conference presentations, and papers (Aronson et al., 2013; Rhodes, 2004; Rhodes, Alonzo, Mann, Freeman, et al., 2015; Rhodes, Daniel, et al., 2013; Rhodes, Duck, Alonzo, Daniel, et al., 2013; Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2007; Rhodes et al., 2006; Rhodes, Kelley, et al., 2012; Rhodes, Leichliter, Sun, & Bloom, 2016; Rhodes et al., 2014; Rhodes, Song, Nam, Choi, & Choi, 2015; Rhodes, Vissman, et al., 2011; Tanner et al., 2016), for 24 funded community-engaged research projects. These projects are outlined in Table 2. These projects were funded by the US CDC, US National Institutes of Health (NIH), and foundations, including the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, amfAR: the Foundation for AIDS Research, The Cone Foundation, and the Pfizer Foundation. Partnership members examined these documents and used an iterative approach with review, discussion, and re-review of emergent steps. The process continued until the steps were identified, refined, and described. A component of our analysis was to identify steps that crossed studies, had potential to be generalizable to other studies, and could serve as a guide for future studies.

Table 2.

Community-engaged studies included in development of this 15-step process

| Abbreviated study title | Study number/Funder | Dates |

|---|---|---|

| HIV prevention among Latina transgender women: A locally developed intervention | U01PS005137 | 2016-present |

| Tailored use of social media to improve engagement in care for ethnically/racially diverse young MSM and transgender women with HIV | H97HA28896 | 2015-present |

| Improving engagement in care and outcomes for ethnically/racially diverse young MSM and transgender women with HIV through social media | Cone Foundation | 2015-present |

| Immigrant access to health services community report-backs and regional forums | Kate B. Reynolds Charitable Trust | 2013-2014 |

| Photovoice with Latina transgender women | R01MH087339 | 2013 |

| Exploring health care access among Koreans in the Triad using CBPR | Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute | 2012-2013 |

| Evaluating an intervention to increase HIV testing through chat-room promotion | R01MH092932 | 2011-2016 |

| Analyzing the impact of immigration enforcement by local officials on access to care among Latinos | Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Public Health Law Research Program | 2011-2012 |

| HIV prevention among Latino MSM: Evaluation of a locally developed intervention | U01PS001570/CDC | 2010-2017 |

| Using CBPR to reduce HIV risk among immigrant Latino MSM | R01MH087339 | 2010-2017 |

| Exploring HIV prevention among Black, Latino, and White MSM | NC Department of Health and Human Services | 2009-2010 |

| Partnership approach to reducing HIV disparities among Latino men | R24MD002774 | 2008-2018 |

| CBPR and the internet: Increasing HIV testing through chat room-based promotion | R21MH082689 | 2008-2010 |

| Trust and mistrust of evidence-based medicine among Latinos with HIV | 107201-44-RGAT, amfAR: The Foundation for AIDS Research | 2008-2009 |

| HIV/AIDS prevention with African American men attending college: A CBPR approach | UR6PS000690 | 2007-2011 |

| Enhancement of client services through comprehensive risk counseling | Pfizer Foundation | 2007-2010 |

| Trabajando Juntos: Working together for health disparity reduction among Latinos | R21MH079827 | 2007-2009 |

| Use of prescription drugs obtained from non-medical sources for the treatment of STDs among rural Latinos in the Southeast | 02885-08/CDC | 2007-2008 |

| HIV among rural Latino gay men and MSM in the Southeast | R21HD049282 | 2006-2008 |

| HoMBReS: A lay health advisor approach to HIV and STD prevention | TS-1023/CDC | 2003-2007 |

| CyBER M4M (Cyber-Based Education and Referral/Men for Men) | P30AI50410 | 2003-2006 |

| Men as Navigators (MAN) for Health | R06/CCR421449 | 2003-2006 |

| HIV and community capacity among Latinos | Wake Forest Venture Funds | 2003-2005 |

| Sexual health among Latino men in NC | Kellogg Foundation | 2001-2003 |

RESULTS

Identified Steps of Community-engaged Research

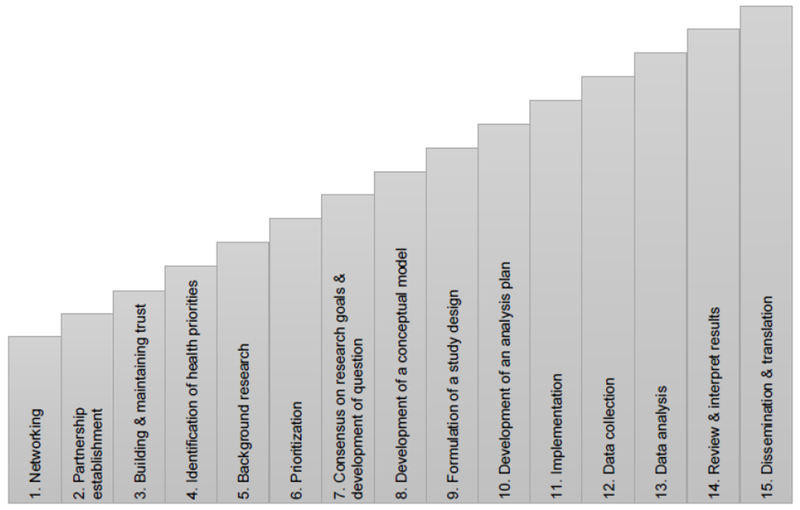

Our partnership identified 15 steps to guide community-engaged research (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Steps of community engaged-research to reduce health disparities and promote health equity

1. Networking.

The first step in the community-engaged research process requires the development of a network of persons with similar areas of interest or concern. Community-engaged research relies on an alignment among community needs, priorities, and resources and expertise of partners. Thus, a critical foundation of community-engaged research is identifying potential partners. We have found that casting a wide net ensures a broad spectrum of perspectives and expertise necessary to effectively conduct research to understand health disparities and promote community and population health.

Our partnership is based on a firm foundation developed by the NC Community-Based Public Health Initiative (CBPHI). Members of a NC CBPHI-organized community-engaged research partnership that had a history of successfully implementing diabetes interventions within African American/Black faith communities in rural NC (Margolis et al., 2000; Parker et al., 1998) wanted to explore the needs, priorities, and assets of the growing Latino community (Rhodes, Eng, et al., 2007; Rhodes et al., 2006). However, Latino community members were not sufficiently represented within the partnership. Thus, much effort went into the process of networking with Latino community members. Partners met informally one-on-one and held small group meetings with Latino community members to network and discuss working together to identify needs, priorities, and assets. For example, partners approached the president of a large recreational soccer league (>1,800 members) to talk about the partnership, his potential involvement (and the potential involvement of his soccer league), and the potential to explore and address the priorities and needs of the Latino community. Partners met with the league president every two weeks over dinner, explaining his potential role in the partnership. After each dinner, he requested time to think about involvement of his league and scheduled subsequent dinner meetings. After eight months of having dinner every two weeks with partnership representatives, the president brought his wife to dinner. She curiously asked, “Why do you continue to take my husband to dinner?” Hearing the partners discuss his role and the importance of his involvement in third person resonated with him. His wife also approved of his involvement, and he joined the partnership. This was an important lesson for the partnership; although the partners understood why the soccer league president would be critical, he did not have the same understanding. This community had been neglected; they were not accustomed to others wanting to work in authentic partnership with them.

2. Partnership establishment.

Sound community-engaged research is facilitated by the establishment, maintenance, and commitment of a community-academic partnership comprised of community members; representatives of organizations, agencies, and businesses; providers and practitioners, and academic researchers. Partners work together in a participatory manner, providing diverse perspectives, insights, and experiences throughout the research process (Seifer & Maurana, 2000). Like other partnerships (Seifer & Maurana, 2000), our partnership established and adheres to principles to help facilitate and guide the process of engagement and participation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Principles of partnership

| To reduce health disparities, increase health equity, and promote community and population health, we strive to build and maintain trust among each of us—community members, organization and agency representatives, clinicians, and academic researchers—through |

| • Mutual respect and genuineness |

| • Establishing and using formal and informal networks and structures |

| • Transparent processes and clear and open communication |

| • Roles, norms, and processes evolving from the input and agreement |

| • Agreeing on the values, goals, and objectives of research and practice |

| • Building on each’s strengths and assets |

| • Continual feedback |

| • Balancing power and sharing resources |

| • Sharing credit for the accomplishments |

| • Facing challenges together |

| • Incorporating existing environmental structures to address partnership focuses |

| • Taking responsibility for the partnership and its actions |

| • Disseminating findings and conclusions to community members, research and clinical audiences, and policy makers |

3. Building and maintaining trust.

Trust building and maintenance are key to community-engaged research; many communities have felt exploited as “living laboratories” for universities and academic medical centers, and community members and organization representatives may be hesitant to engage with each other and with academic researchers. Relationships between community members, organization representatives, practitioners, and academic researchers may involve informal meetings that allow partners to acknowledge and discuss this history and get to know one another. Community events such as street fairs, church gatherings, and community forums as well as parties and celebrations are ideal places for partners to convene. These types of opportunities show commitment and allow attendees to further know and understand one another. Participation in other non-research activities, such as volunteering with a community organization or serving on local health coalitions, by academic partners, advances genuine and mutually respectful relationships. It also may open other doors by providing further opportunities to identify others who may be committed to working together.

Another longstanding partnership in North Carolina has used an Undoing Racism Training (Peoples Institute for Survival and Beyond) as a strategy for building trust among partners. By participating in the training as a partnership and making a commitment to the processes delineated within the Undoing Racism model, partners better appreciate the contextual challenges faced by communities (e.g., institutional racism); the need for broad and meaningful representation to overcome these challenges; and the roles of transparency, conflict, and cultural humility (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998) within research partnerships (Yonas et al., 2006).

4. Identification of health priorities.

Exploring community member perspectives may yield important insights about what community members perceive as needs, priorities, and assets. Strategies to identify health priorities may include focus groups and in-depth individual interviews. One innovative qualitative methodology that we have used frequently to identify and understand community priorities is photovoice. Photovoice enables participants to record and reflect on community priorities through photographs that they take and group discussion triggered by these photographs. This method provides images of lived experiences and gives an opportunity for participants and others who may be able to support action to collaboratively identify priorities and next steps (Hergenrather, Rhodes, Cowan, Bardhoshi, & Pula, 2009). We have successfully used photovoice with Latino men (Rhodes, Hergenrather, Griffith, et al., 2009) and women (Baquero et al., 2014), persons with HIV (Rhodes, Hergenrather, Wilkin, & Jolly, 2008), Latino transgender persons (Rhodes, Alonzo, Mann, Sun, et al., 2015), Latino (Streng et al., 2004) and non-Latino (Irby et al., In press.) adolescents, and the Korean immigrant community (Rhodes, Song, et al., 2015).

Exploring health priorities can also be done using innovative quantitative methods, such as respondent-driven sampling (RDS), which uses chain-referrals, or initial respondents as “seeds” to yield representative samples and prevalence estimates for populations that may be considered “difficult to reach” by researchers or other outsiders for which no sampling frame exists (e.g., immigrants and Latino MSM and transgender women) (Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2012; Song et al., 2012).

5. Background research.

It is important to explore and analyze community priorities in context. Community priorities should be matched with the aggregate knowledge from organization representatives (e.g., service providers) based in ongoing service delivery and practice, available epidemiologic data, and the academic and grey literatures. Community-engaged research must build upon what is known. Often, academic researchers are hesitant to suggest what they know about community needs. However, we have found that academic researchers who are trusted and active partners often have valuable insights themselves and should share what they know and help community partners develop new understandings through working together. The available epidemiologic data and the literature that academic researchers have ready access to can provide the partnership with critical information to ensure the most informed understanding of health.

6. Prioritization.

Based on what is learned through identifying community priorities and putting these priorities within a larger context of what is known, partners make decisions about issues on which to focus based on the answers from two key questions: (1) What is important? and (2) What is changeable? Although much research is needed that aligns with community priorities, open and honest discussions of what is both important and changeable given interests, talents, and resources are critical.

Without thoughtful prioritization, it is unlikely that community health will be enhanced. For example, our partnership initially began with a clear focus on HIV prevention among Latino men. We knew that HIV among women and youth was important too, but we focused on the population that was initially engaged. We also wanted to begin our research process modestly, incrementally building a history of success. We chose a stepwise approach that moved in a linear manner from formative data collection to intervention design, implementation, and evaluation. This was a carefully orchestrated process because reasonable scopes of work help to ensure early successes that in turn help maintain engagement.

7. Consensus on research goals and development of a research question.

Partners must negotiate and agree upon what they are working toward. For example, within our intervention research, partners agree that we are developing and testing interventions to determine their efficacy. Being clear about this focus is particularly important, given that service providers and practitioners often deliver interventions and programs; they often do not test them to determine their efficacy. Testing an intervention or program adds complexity beyond the challenges typically associated with intervention or program delivery and includes issues related to sample size and statistical power, randomization, measurement, data collection methods, fidelity, and validity. Thus, agreeing on goals and articulating a research question help to frame a project and identify what it will take to meet the goals.

8. Development of a conceptual model.

We found that the development of a conceptual model or logic model allows partners to visually depict the linear process of the research, the resources needed, and the outcomes expected. A conceptual or logic model must incorporate the lived experiences of community members, insights based on ongoing service provision and delivery by providers and practitioners, and theoretical underpinnings. Development of a conceptual model or logic model allows partners to discuss their various assumptions and engage in a process to reconcile perspectives. This step also facilitates the preliminary identification of variables for measurement. The conceptual model and logic model concept is presented and viewed as a fluid resource that may change over time based on new insights.

9. Formulation of a study design.

The next step in the process includes the development of an appropriate study design to answer the agreed-upon research question. This step allows the study to be conducted in a manner that is authentic to what is possible within the community. Rather than developing a study that is not likely to meet objectives, engagement ensures that the most feasible design is chosen to produce the most meaningful findings.

To test interventions, for example, our partnership has utilized two main designs: intervention/delayed-intervention group-randomized trial design and the two-arm randomized intervention-controlled trial design. We have found intervention/delayed-intervention group-randomized trial design (Campbell et al., 2000) to be appealing because it ensures all study participants have access to the intervention over time. Community members want to test interventions, but they want designs that do not neglect the needs of some participants. Thus, many of our studies have used the intervention/delayed-intervention group-randomized trial design.

The second study design our partnership has had success in implementing is the two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) design. During the process of implementing the original HoMBReS intervention (Rhodes, Hergenrather, Bloom, Leichliter, & Montaño, 2009; Rhodes et al., 2006; Rhodes et al., 2016) and prior to our knowing whether the intervention was successful, members of our partnership increased their understanding of the role and importance of using scientific evidence to guide policy, specifically prevention funding priorities. The State of North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services announced the availability of funding for HIV prevention but required applicants to use efficacious interventions. Despite the impact HIV was having on Latino populations, at that time, no efficacious existed to contribute to reducing and eliminating HIV disparities within Latino communities.

The dearth of interventions designed to meet the priorities and needs of Latino communities motivated members of our partnership to develop the HoMBReS-2 intervention and test it using a two-arm RCT (Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011). This type of design would not have been feasible in our community previously; however, working closely, partners built trust among one another and increased appreciation of the value of scientific evidence. Partners recognized that communities that had interventions designed specifically for them would be more able to access state HIV prevention funding to implement needed interventions and programs. Members of the partnership decided that they wanted to develop an intervention and test it in a manner that would begin to build evidence. As a Latino partner noted,

“Latinos want and need information and help to be safe, but nothing exists that we can point to that shows promise in saving the lives of Latinos. Other communities have programs that are based on science. These communities came together to develop these programs and prove that they work. They have demonstrated to outsiders [policy makers] that they work. Now these programs can help other communities because policy makers provide resources. The Latino community deserves the same high quality programming that is based in strong research. To expect anything for ourselves would be wrong; we would be saying that Latinos should not have the same level of programming.”

10. Development of an analysis plan.

Along with formulating a study design, working together allows the most community-relevant outcomes variables to be selected and the most meaningful analysis plan to be developed. Insights about variables, their measurement, confounders, and how analyses should proceed can help to ensure the most informed process for answering the agreed-upon research question and thus, again, the most meaningful study findings.

11. Implementation.

After thorough planning and preparation, the next step that we identified includes the implementation of the research. Engagement ensures ongoing study oversight and problem solving by partners. When faced with challenges to meet research benchmarks, engagement ensures creative solutions that consider the potential ramifications to the research and the community from multiple perspectives.

An example of our use of creative problem solving occurred as we began implementing the HOLA intervention (Rhodes, Daniel, et al., 2013; Tanner et al., 2014). While our previous studies included substantial proportions of transgender persons (Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2010; Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2012), we realized that our the HOLA intervention did not acknowledge and address the concerns and contexts of transgender persons in the same way it did for gay, bisexual, and other MSM. For instance, the “H” in our HOLA stood for “hombres” (men) (Rhodes, Daniel, et al., 2013), and yet, some participants who met inclusion criteria did not self-identify as men. When we realized our error, we quickly but thoughtfully revised the intervention curriculum. We no longer defined and gave meaning to the letters within the acronym HOLA in the intervention title, and we removed the meaning of the acronym HOLA from logos, t-shirts, caps, and all printed materials. We also revised all facilitator language to include “transgender persons,” rather than only “gay, bisexual, and other MSM” in Spanish. We updated information to include rates of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among transgender persons, revised role-plays to include transgender scenarios, and ensured that all visuals included images of transgender women. We also successfully developed and implemented a transgender photovoice project to better understand their needs, priorities, and assets (Rhodes, Alonzo, Mann, Sun, et al., 2015).

Our work with Latina transgender women has led to an intervention that we are currently testing titled, ChiCAS: Chicas Creando Acceso a la Salud [Girls: Girls Creating Access to Health]). ChiCAS is designed to increase access to medically supervised hormone therapy and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among Latina transgender women.

12. Data collection.

In most cases, data collection is a component within implementation, but it is highlighted as a separate step to highlight the importance of engagement within data collection to increase the overall accuracy of collected data and thus the usefulness of collected data. Although academic researchers often have “curiosities” that they would like to answer, community-engaged research ensures that measurement focuses on important and relevant variables, participant burden is minimized, and measures have ecologic validity (Rhodes, Malow, & Jolly, 2010). Our partnership reduces participant burden and thus the potential of incomplete or meaningless responses to surveys by using measures that assess variables that are most germane to the research being conducted and are parsimonious.

13. Data analysis.

Engagement during data analysis ensures the analysis plan “makes sense”, allows for refinement based on new understandings among partners, and can include participation throughout the data analysis process. In a qualitative study of sexual health among Latino men (Rhodes, Eng, et al., 2007), an ad hoc committee of partners served as the data analysis team. Members of this team consisted of between 1 and 3 representatives from each of the following groups: the local lay Latino community, a local Latino soccer league, a Latino-serving community organization, the local health department, an AIDS service organization, and a university. Because some members of analysis team were not bilingual, each read and coded transcripts in his or her own language. The analysis aimed to identify common themes through coding text. Conducting the analyses separately, analysis team members read and reread the transcripts to identify potential codes, convened to create a common coding system and data dictionary, and then separately assigned agreed-upon codes to relevant text. The academic researcher used Nvivo, an analytic software program, to code and retrieve text. Similarities and differences across transcripts were examined and codes and themes revised accordingly. Analysis team members met to compare and revise themes. One theme was the positive role of “traditional” notions of masculinity that are often identified as having negative influences on men’s health. Instead, the partnership approach teased out the positive aspects of masculinity, such as respecting oneself and taking care of one’s family, which are linked to immigrating to the United States.

14. Review and interpret results.

This step contributes to the accuracy of findings by allowing members of the partnership to understand, refine, and when warranted, provide alternate explanations and interpretations. Working alone, an academic researcher may misunderstand and/or misinterpret results, but through the process of partners working together to review and interpret results, results and their interpretations are more likely to be accurate. Working together also allows partners to identify next steps, including how, when, and where to present the findings, as well as directions for subsequent research.

During the qualitative study of sexual health among Latino men (Rhodes, Eng, et al., 2007) described in step 13, draft themes were written on flipcharts so that partners could review, discuss, revise, and interpret them during four iterative discussions. During each step of the process, information generated was combined with partners’ lived experiences and cultural knowledge as well as previous research to inform theme development and derive interpretations. This approach yielded five themes, which the partnership subsequently employed in sequent interventions.

15. Dissemination and translation.

Community-engaged research helps to ensure that presentations and peer-reviewed papers for scientific audiences are not the only channels used for dissemination. In our partnership, we support broad dissemination with members of the partnership participating in dissemination efforts at all levels. For example, community members and organization representatives may participate in national and international and presentations for scientific audiences along with academic researchers while academic researchers may participate in presentations for practice-based and community audiences. Community members, organization representatives, and academic researchers also participate in the preparation and authorship of peer-reviewed papers, policy briefs, and practice-based newsletters.

DISCUSSION

Discovery within community-engaged research occurs both as the research process unfolds and as research goals are met in the form of study outcomes. Learning throughout the process includes how to work together more effectively, how to problem-solve, and how to accomplish study-related tasks. Thus, representatives from the community and community organizations contribute and learn throughout the process; they may be involved not only in overcoming hurdles related to recruitment, for example, but may be involved in study conceptualization, design and conduct, data analysis and interpretation, and the dissemination of findings.

Community-engaged research holds much promise for contributing to community and population health. Because community-engaged research is inherently translational, it ensures that basic, more formative research is conducted with a goal of practical use to improve health. Research may begin with an assessment of needs and to understand phenomena through community perceptions and epidemiologic data, but research findings must be translated into action for positive community change. There is a long history of research designed to answer interesting and potentially important questions, but more often than not, those answers have not been consistently translated into community and population health. It is not sufficient to solely generate knowledge; rather, we must commit to action, including individual, group, and community action, as well as policy and social change. Though the use of findings can be slow, through engagement, change may occur. That change, however, can be difficult to quantify.

Best practices for community-engaged research will continue to evolve. Our systematic approach to engagement throughout the research process serves as a guide. Each step is complicated, and our work as a partnership has not been without challenges. For example, partners face the realities of HIV infection every day and know that something must be done for the communities each partner belongs to. The slow pace of securing research funding and conducting sound research is an ongoing frustration. Furthermore, communities themselves are not infallible; community members and members of community-engaged research partnerships may have strongly held prejudices about one another that require ongoing attention and work.

However, our partnership has had great success using systematic community-engaged research processes. We are committed to community-engaged research as an innovative approach because it maximizes the probability that what we do together is based on what the community itself sets as a priority; is more informed because of the sharing of broad perspectives, insights, and experiences; builds capacity of all partners to solve community problems, use community assets, and conduct meaningful research; and promotes sustainability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the broader membership of the community-engaged research partnership that the authors are part of. Funding for this commentary includes CDC (TS-1023 [through a cooperative agreement with Association for Prevention Teaching and Research], U01PS005137, UR6PS000690, NU22PS005115, and U01PS001570); HRSA (H97HA28896); NIH (UL1TR001420, R01MH092932, R01MH087339, R24MD002774, R21MH082689, and R21MH079827), and the Cone Health Foundation.

Contributor Information

Scott D. Rhodes, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Amanda E. Tanner, University of North Carolina Greensboro

Lilli Mann-Jackson, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Jorge Alonzo, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Florence M. Simán, El Pueblo

Eunyoung Y. Song, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Jonathan Bell, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Megan B. Irby, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Aaron T. Vissman, Talbert House

Robert E. Aronson, Taylor University

REFERENCES

- Aronson RE, Rulison KL, Graham LF, Pulliam RM, McGee WL, Labban JD, Rhodes SD (2013). Brothers Leading Healthy Lives: Outcomes from the pilot testing of a culturally and contextually congruent HIV prevention intervention for black male college students. AIDS Education and Prevention, 25(5), 376–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balas EA, Weingarten S, Garb CT, Blumenthal D, Boren SA, & Brown GD (2000). Improving preventive care by prompting physicians. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160(3), 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baquero B, Goldman SN, Simán F, Muqueeth S, Eng E, & Rhodes SD (2014). Mi Cuerpo, Nuestro Responsabilidad: Using Photovoice to describe the assets and barriers to reproductive health among Latinas. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 7(1), 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, Kinmonth AL, Sandercock P, Spiegelhalter D, & Tyrer P (2000). Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. British Medical Journal, 321(7262), 694–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. (2011). Principles of Community Engagement (Second edition ed.): Washington: Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Committee to Review the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Institute of Medicine. (2013). The CTSA Program at NIH: Opportunities for Advancing Clinical and Translational Research. doi: NBK144067 [bookaccession] 10.17226/18323 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergenrather KC, Rhodes SD, Cowan CA, Bardhoshi G, & Pula S (2009). Photovoice as community-based participatory research: a qualitative review. American Journal of Health Behavior, 33(6), 686–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irby MB, Hamlin D, Rhoades L, Summers P, Rhodes SD, & Daniel S (In press). Violence as a health disparity: Adolescents’ perceptions of violence depicted through photovoice. Journal of Community Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kost RG, Leinberger-Jabari A, Evering TH, Holt PR, Neville-Williams M, Vasquez KS, Tobin JN (2017). Helping basic scientists engage with community partners to enrich and accelerate translational research. Academic Medicine, 92(3):374–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis LH, Stevens R, Laraia B, Ammerman A, Harlan C, Dodds J, Pollard M (2000). Educating students for community-based partnerships. Journal of Community Practice, 7(4), 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Parker EA, Eng E, Laraia B, Ammerman A, Dodds J, Margolis L, & Cross A (1998). Coalition building for prevention: lessons learned from the North Carolina Community-Based Public Health Initiative. Jorunal of Public Health Management and Practice, 4(2), 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peoples Institure for Survival and Beyond Undoing Racism. Available at: http://www.pisab.org/.

- Rhodes SD (2004). Hookups or health promotion? An exploratory study of a chat room-based HIV prevention intervention for men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 16(4), 315–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD (2012). Demonstrated effectiveness and potential of CBPR for preventing HIV in Latino populations In K. C. Organista (Ed.), HIV Prevention with Latinos: Theory, Research, and Practice (pp. 83–102). New York, NY: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD (2014). Authentic engagement and community-based participatory research for public health and medicine In Rhodes SD (Ed.), Innovations in HIV Prevention Research and Practice through Community Engagement (pp. 1–10). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Alonzo J, Mann L, Freeman A, Sun CJ, Garcia M, & Painter TM (2015). Enhancement of a locally developed HIV prevention intervention for Hispanic/Latino MSM: A partnership of community-based organizations, a university, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention AIDS Education and Prevention, 27(4), 312–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Alonzo J, Mann L, Song E, Tanner AE, Arellano JE, Painter TM (2017). Small-group randomized controlled trial to increase condom use and HIV testing among Hispanic/Latino gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 107(6), 969–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Alonzo J, Mann L, Sun CJ, Simán FM, Abraham C, & Garcia M (2015). Using photovoice, Latina transgender women identify priorities in a new immigrant-destination state. International Journal of Transgenderism 16(2), 80–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Daniel J, Alonzo J, Duck S, Garcia M, Downs M, Marsiglia FF (2013). A systematic community-based participatory approach to refining an evidence-based community-level intervention: The HOLA intervention for Latino men who have sex with men. Health Promotion Practice, 14(4), 607–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Duck S, Alonzo J, Daniel J, & Aronson RE (2013). Using community-based participatory research to prevent HIV disparities: Assumptions and opportunities identified by The Latino Partnership. Journal of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndromes, 63(Supplement 1), S32–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Duck S, Alonzo J, Downs M, & Aronson RE (2013). Intervention trials in community-based participatory research In Blumenthal D, DiClemente RJ, Braithwaite RL & Smith S (Eds.), Community-Based Participatory Research: Issues, Methods, and Translation to Practice (pp. 157–180). New York: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Eng E, Hergenrather KC, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Montano J, & Alegria-Ortega J (2007). Exploring Latino men’s HIV risk using community-based participatory research. American Journal of Health Behavior, 31(2), 146–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Aronson RE, Bloom FR, Felizzola J, Wolfson M, McGuire J (2010). Latino men who have sex with men and HIV in the rural south-eastern USA: findings from ethnographic in-depth interviews. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 12(7), 797–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, & Montaño J (2009). Outcomes from a community-based, participatory lay health advisor HIV/STD prevention intervention for recently arrived immigrant Latino men in rural North Carolina, USA. AIDS Education and Prevention, 21(Supplement 1), 104–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Duncan J, Ramsey B, Yee LJ, & Wilkin AM (2007). Using community-based participatory research to develop a chat room-based HIV prevention intervention for gay men. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 1(2), 175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Griffith D, Yee LJ, Zometa CS, Montaño J, & T., V. A (2009). Sexual and alcohol use behaviours of Latino men in the south-eastern USA. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 11(1), 17–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Montano J, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Bloom FR, Bowden WP (2006). Using community-based participatory research to develop an intervention to reduce HIV and STD infections among Latino men. AIDS Educ Prev, 18(5), 375–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Wilkin AM, & Jolly C (2008). Visions and Voices: Indigent persons living With HIV in the southern United States use photovoice to create knowledge, develop partnerships, and take action. Health Promot Pract, 9(2), 159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Kelley C, Simán F, Cashman R, Alonzo J, Wellendorf T, Reboussin B (2012). Using community-based participatory research (CBPR) to develop a community-level HIV prevention intervention for Latinas: A local response to a global challenge. Womens Health Issues, 22(3), 293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Leichliter JS, Sun CJ, & Bloom FR (2016). The HoMBReS and HoMBReS Por un Cambio interventions to reduce HIV disparities among immigrant Hispanic/Latino men. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(1), 51–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Malow RM, & Jolly C (2010). Community-based participatory research: a new and not-so-new approach to HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment. AIDS Education and Prevention, 22(3), 173–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Mann-Jackson L, Alonzo J, Siman FM, Vissman AT, Nall J, … Tanner A (2017). The ENGAGED for CHANGE process for developing interventions to reduce health disparities. AIDS Education and Prevention, 29(6), 491–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Mann L, Alonzo J, Downs M, Abraham C, Miller C, Reboussin BA (2014). CBPR to prevent HIV within ethnic, sexual, and gender minority communities: Successes with long-term sustainability In Rhodes SD (Ed.), Innovations in HIV Prevention Research and Practice through Community Engagement (pp. 135–160). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, McCoy TP, Hergenrather KC, Vissman AT, Wolfson M, Alonzo J, Eng E (2012). Prevalence estimates of health risk behaviors of immigrant Latino men who have sex with men. Journal of Rural Health, 28(1), 73–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, McCoy TP, Vissman AT, DiClemente RJ, Duck S, Hergenrather KC, Eng E (2011). A randomized controlled trial of a culturally congruent intervention to increase condom use and HIV testing among heterosexually active immigrant Latino men. AIDS and Behavior, 15(8), 1764–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Song E, Nam S, Choi SJ, & Choi S (2015). Identifying and intervening on barriers to healthcare access among members of a small Korean community in the southern USA. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(4), 484–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Vissman AT, Stowers J, Miller C, McCoy TP, Hergenrather KC, Eng E (2011). A CBPR partnership increases HIV testing among men who have sex with men (MSM): Outcome findings from a pilot test of the CyBER/testing Internet intervention. Health Education and Behavior, 38(3), 311–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifer SD, & Maurana CA (2000). Developing and sustaining community-campus partnerships: Putting principles into practice. Partnership Perspectives, 1(2), 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Song EY, Vissman AT, Alonzo J, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, & Rhodes SD (2012). The use of prescription medications obtained from non-medical sources among immigrant Latinos in the rural southeastern US. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 23(2), 678–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streng JM, Rhodes SD, Ayala GX, Eng E, Arceo R, & Phipps S (2004). Realidad Latina: Latino adolescents, their school, and a university use photovoice to examine and address the influence of immigration. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 18(4), 403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner AE, Mann L, Song E, Alonzo J, K S, Arellano E, Rhodes SD (2016). weCare: A social media-based intervention designed to increase HIV care linkage, retention, and health outcomes for racially and ethnically diverse young MSM. AIDS Education and Prevention, 28(3), 216–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner AE, Reboussin BA, Mann L, Ma A, Song E, Alonzo J, & Rhodes SD (2014). Factors influencing healthcare access perceptions and care-seeking behaviors of Latino sexual minority men and transgender individuals: HOLA intervention baseline findings. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 25(4), 1679–1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervalon M, & Murray-Garcia J (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh-Shevrin C, Islam NS, Nadkarni S, Park R, & Kwon SC (2015). Defining an integrative approach for health promotion and disease prevention: a population health equity framework. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 26(2 Suppl), 146–163. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson M, Wagoner KG, Rhodes SD, Egan KL, Sparks M, Ellerbee D, Yang E (2017). Coproduction of research questions and research evidence in public health: The study to prevent teen drinking parties. Biomedical Research International, 2017, 3639596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonas MA, Jones N, Eng E, Vines AI, Aronson R, Griffith DM, DuBose M (2006). The art and science of integrating Undoing Racism with CBPR: challenges of pursuing NIH funding to investigate cancer care and racial equity. Journal of Urban Health, 83(6), 1004–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]