Abstract

Objectives:

To examine contraceptive methods used across sexual orientation groups.

Study Design:

We collected data from 118,462 female participants in two longitudinal cohorts—the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) 2 (founded in 1989, participants born 1947–1964) and NHS3 (founded in 2010, born 1965–1995). We used log-binomial models to estimate contraceptive methods ever used across sexual orientation groups and cohorts, adjusting for age and race.

Results:

Lesbians were the least likely of all sexual orientation groups to use any contraceptive method. Lesbians in NHS2 were 90% less likely than heterosexuals to use long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs; adjusted risk ratio [aRR]; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.10 [0.04, 0.26]) and results were similar for other contraceptive methods and in the NHS3 cohort. Compared to the reference group of completely heterosexual participants with no same-sex partners, those who identified as completely heterosexual with same-sex partners, mostly heterosexual, or bisexual were generally more likely to use any method of contraception. Use of LARCs was especially striking across sexual minority groups, and, with the exception of lesbians, they were more likely to use LARCs; as one illustration, NHS3 bisexuals were more than twice as likely to use LARCs (aRR [95% CI]: 2.01 [1.67, 2.42]).

Conclusions:

While certain sexual minority subgroups (e.g., bisexuals) were more likely than heterosexuals to use contraceptive methods such as LARCs, lesbians were less likely to use any method.

Implications:

Many sexual minority patients need contraceptive counseling and providers should ensure to offer this counseling to patients in need, regardless of sexual orientation.

Keywords: Sexual-minority women, Bisexual, Lesbian, Contraception uptake, Health disparity

1. INTRODUCTION

Sexual minority (e.g., bisexual, lesbian) women are as likely as their heterosexual peers to have ever had sexual intercourse with men[1,2] and are more likely to experience a teen pregnancy[2–7] and sexually transmitted infection (STI)[8–12]. Additionally, sexual minority women are less likely than heterosexual women to receive preventive gynecologic care such as Pap tests[10,13–15]. Our research team has recently documented[16] that these Pap test disparities are partly due to differences in hormonal contraceptive use, particularly less hormonal contraceptive use by lesbians. By not seeking out healthcare for contraception, these lesbian patients miss opportunities for other gynecologic care including STI screenings and Pap tests. While contraceptive and other gynecological care should not be interdependent[17], patients often come into the healthcare system through contraceptive counseling[18].

While our previous research explored hormonal contraceptives[16], little research has been conducted on the full range of contraceptive methods across sexual orientation groups. Researchers have hypothesized[19–21] that sexual minority women may be less likely than heterosexuals to use contraceptives, particularly methods that regularly bring them into the healthcare system for preventive care. However, initial studies to address this concern have often suffered from critical limitations including small samples, limited statistical power, convenience samples from sexual minority sources, coverage of only a single geographic region, cross-sectional study design, and inadequate sexual orientation measurement (e.g., defining sexual minorities solely through same-sex partners as opposed to including the other dimensions of attraction and self-identification).

This study aims to fill these gaps by documenting the full range of contraceptive methods used across sexual orientation groups. We utilized data from three U.S. longitudinal cohort studies with over 125,000 female participants who provided detailed data on their sexual orientation and contraceptive use.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Population: NHS2 and NHS3 Combined Analytic Sample

The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) 2 began in 1989 when 116,430 female nurses, aged 25 to 42 years, completed questionnaires about their medical history and health behaviors. NHS3 began in 2010 as an open-cohort with female nurses aged 19 to 46 years; current enrollment includes 45,080 women. Data collection is ongoing via annual or biennial questionnaires in both cohorts that are mailed and online. When participants fail to respond to initial mailings, study staff implement extensive follow-up procedures. Detailed information on the initial recruitment, response rates, and survey intervals has been previously published[22,23].

The current analysis was limited to female participants who reported their sexual orientation and information regarding contraceptive use between enrollment at baseline and the end of follow-up in 2017 (N=118,462). This study was approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sexual orientation

We included the following question on the NHS2 questionnaire in 1995 and 2009, after pilot testing[24]: “Whether or not you are currently sexually active, what is your sexual orientation or identity? (Please choose one answer) (1) Heterosexual, (2) Lesbian, gay, or homosexual, (3) Bisexual, (4) None of these, (5) Prefer not to answer.” No information about the sex of sexual partners was collected in NHS2.

Detailed information about sexual orientation was collected on the fifth follow-up questionnaire in NHS3 starting in 2013. The item was adapted from the Minnesota Adolescent Health Survey[25], which asks about feelings of attraction and identity with six mutually exclusive response options (completely heterosexual, mostly heterosexual, bisexual, mostly homosexual, completely homosexual, and unsure). We combined data from this item with a question about the sex of sexual partners. Partners reported as “I have not had sexual contact with anyone,” “females,” “males,” and “males and females” in their lifetime. We combined the item about feelings of attraction/identity with this sexual partner item to create an additional sexual minority group (completely heterosexuals with same-sex partners). The term “sexual contact” was not defined for the participants so this was not restricted to penile-vaginal sexual intercourse.

For the current analyses, we used the participant’s most recent report of sexual orientation (e.g., NHS2 2009, NHS3 questionnaire 5). If data were missing, we imputed with the most recent previous response. Sexual orientation groups were modeled as: completely heterosexual (included NHS3 “completely heterosexual with no same-sex partners” and NHS2 “heterosexual”); completely heterosexual with same-sex partners (included NHS3 corresponding category); mostly heterosexual (included NHS3 corresponding category); bisexual (included NHS2 and NHS3 corresponding category); and lesbian (included NHS3 “mostly homosexual” and “completely homosexual” and NHS2 “lesbian, gay, or homosexual”). When data were available on the sex of sexual partners, we also ran sensitivity analyses excluding women who never in their lifetime had male sexual partners. Additionally, we ran sensitivity analyses using different sexual orientation reports (e.g., ever reporting a sexual minority status).

2.2.2. Contraceptive use

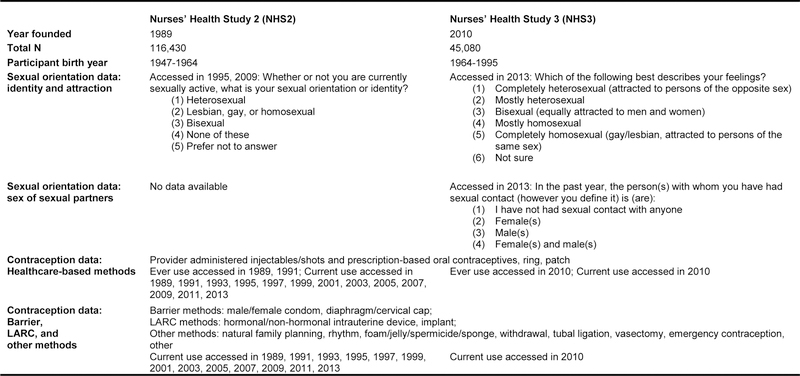

NHS2 first assessed contraceptive use at baseline in 1989 and NHS3 in the second follow-up questionnaire starting in 2010. Each cohort assessed contraceptive methods slightly differently, often due to changes in the methods that were available on the market at the time (see Figure 1). We provided participants with additional text describing these methods including male condom, female condom, oral contraceptive (pill), withdrawal, injectable/shots (e.g., Depo-Provera), implant (e.g., Implanon), periodic abstinence-calendar rhythm, periodic abstinence-natural family planning, patch (e.g., Ortho Evra), ring (e.g., Nuva Ring), hormonal intrauterine device (IUD; e.g., Mirena), non-hormonal IUD (e.g., ParaGuard), foam/jelly/spermicide/ sponge (e.g., Today sponge), diaphragm/cervical cap, emergency contraception (e.g., Plan B), permanent female (e.g., tubal ligation) and male (e.g., vasectomy) contraception, other, and none. Ever use of oral contraceptives was repeatedly assessed in NHS2 (1989, 1991) and NHS3 participants reported ever use on the second follow-up questionnaire. Participants’ use of barrier (e.g., condoms), long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC), and other methods was assessed through reports of current use in particular questionnaire waves.

Figure 1.

Key study design features of the Nurses’ Health Study 2 and 3 Nurses’ Health Study 2 (NHS2)

Abbreviations: Nurses’ Health Study 2 (NHS2); Nurses’ Health Study 3 (NHS3); long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC)

Given elevated STI risk[8–12] among sexual minority women, we first examined barrier methods. Then, in order to examine methods that may facilitate regular healthcare access, we grouped methods that usually entail regular contact with a healthcare provider (e.g., provider administered injectables/shots and prescription-based oral contraceptives [OCs], ring, and patch). Next, we collapsed all LARC methods (i.e., hormonal IUD, implant, non-hormonal IUD); these highly-efficacious methods were of interest due to sexual minority women’s elevated teen pregnancy risk[2–7] though do not require regular contact with a healthcare provider. Finally, due to limited statistical power, we grouped all other methods (i.e., natural family planning, rhythm, foam/jelly/spermicide/sponge, withdrawal, tubal ligation, vasectomy, emergency contraception, other); sensitivity analyses excluded permanent methods (i.e., tubal ligation, vasectomy) due to their distinct efficacy from the other methods in that category.

We grounded the above contraceptive categories in the existing literature on sexual orientation-related health disparities and therefore there are slight differences from common categorizations in the family planning literature. Therefore, we also analyzed contraceptive methods according to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) tiered effectiveness chart[26]. Tier 1 included LARCs (i.e., hormonal/non-hormonal IUD, implant) as well as tubal ligation and vasectomy. Tier 2 was the equivalent of our healthcare-base category with contraceptives, shots, ring, and patch. Tier 3 included barriers (i.e., male/female condom, diaphragm/cervical cap) as well as natural family planning and rhythm. Tier 4 included foam/jelly/spermicide/sponge and withdrawal.

The primary analysis focused on lifetime ever use of each method but we also examined current use as reported on the most recent questionnaire. Individuals could report multiple contraceptive methods and therefore could be counted in multiple categories. For example, a participant might report using oral contraceptives once on a questionnaire and be categorized as “ever using a healthcare-based method” but then report not using any contraceptives on future questionnaires and be categorized as “ever using none”.

2.2.3. Confounders

Potential confounders included baseline age (in years) and race/ethnicity (White, another race/ethnicity). Data were not available on additional covariates, such as health insurance, that may explain (i.e., mediate) differences in contraception use across sexual orientation groups. To account for differences in when the data were collected, we stratified the data by cohort (i.e., NHS2, NHS3). In sensitivity analyses, we further adjusted for sexual behavior including age at coitarche and number of sexual partners (male and/or female partners). If a participant’s data were missing for potential confounders, data were imputed from previous questionnaire years; if no such data were available for a participant, then multiple imputation procedures were used.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

We first examined the frequency of ever using each of the contraceptive method categories across sexual orientation groups. We used multivariable regression from log-binomial models to calculate adjusted risk ratios (aRR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). When models did not converge, we used log-Poisson models, providing consistent but not fully efficient estimates[27].

Then, we calculated the risk ratios of ever using each contraceptive method by sexual orientation groups (referent=completely heterosexual with no same-sex partners), adjusting for potential confounders. We also calculated adjusted risk ratios for current use of the different contraceptive methods. Next, we ran a number of sensitivity analyses. We restricted estimates to participants who had male sexual partners and also calculated estimates after adjusting further for sexual behavior (i.e., age at coitarche, number of sexual partners). Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3. RESULTS

A total of 118,462 participants were included in our sample from NHS2 and NHS3 (see Table 1). The NHS2 participants (N=99,850) were born between 1947–1964 (mean baseline age in 1989: 34.5 years) and NHS3 participants (N=18,612) were born 1964–1995 (mean baseline age in 2010: 33.5 years). Healthcare-based methods were the most commonly ever used contraceptive method in both cohorts (see Table 2) with nearly 90% of participants reporting such use. Other methods (e.g., vasectomy and tubal ligation) were the second most commonly ever used contraceptive method.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of female participants in the U.S.-based Nurses’ Health Study 2 and 31 by sexual orientation group.

| Total N=118,462 | Heterosexual (NHS2) or Completely Heterosexual with no same-sex partners (NHS3) | Completely Heterosexual with same-sex partners | Mostly Heterosexual | Bisexual | Lesbian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS2 (n=99,850) | (n=98,509, 98.7%) | (n=415, <1%) | (n=926, 0.9%) | ||

| Age at baseline2, Range: 24–44 | 34.4 (4.7) | 34.9 (4.7) | 35.1 (4.5) | ||

| White race/ethnicity | 91,346 (94.1) | 382 (93.6) | 876 (95.7) | ||

| NHS3 (n=18,612) | (n=15,288, 82.1%) | (n=450, 2.4%) | (n=2,171, 11.7%) | (n=361, 1.9%) | (n=342, 1.8%) |

| Age at baseline2, Range: 18–52 | 33.6 (7.2) | 33.6 (6.7) | 32.4 (6.7) | 32.9 (6.4) | 35.2 (7.2) |

| White race/ethnicity | 14,274 (94.4) | 429 (96.6) | 2,053 (95.3) | 344 (96.6) | 316 (93.8) |

Age data presented as mean years (standard deviation) and race/ethnicity data presented as n (%).

Nurses’ Health Study 2 (NHS2) participants were born 1947–1964 and Nurses’ Health Study 3 (NHS3) 1964–1995.

Baseline: NHS2 (1989) and NHS3 (2010).

Table 2.

Frequency1 of ever using contraceptive methods among female participants in the U.S.-based Nurses’ Healthy Study 2 and 32 by sexual orientation group.

| Total N=118,462 | Heterosexual (NHS2) or Completely Heterosexual with no same-sex partners (NHS3) | Completely Heterosexual with same-sex partners | Mostly Heterosexual | Bisexual | Lesbian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS2 (n=99,850) | (n=98,509, 98.7%) | (n=415, <1%) | (n=926, 0.9%) | ||

| Contraceptive Method3 | |||||

| Barrier4 | 39,087 (39.7) | 164 (39.5) | 114 (12.3) | ||

| Healthcare-based | 86,633 (87.9) | 353 (85.1) | 629 (67.9) | ||

| LARC | 4,601 (4.7) | 19 (4.6) | 4 (0.4) | ||

| Other | 76,517 (77.7) | 280 (67.5) | 259 (28.0) | ||

| None | 98,147 (99.6) | 414 (99.8) | 926 (100.0) | ||

| NHS3 (n=18,612) | (n=15,288, 82.1%) | (n=450, 2.4%) | (n=2,171, 11.7%) | (n=361, 1.9%) | (n=342, 1.8%) |

| Contraceptive Method3 | |||||

| Barrier4 | 2,179 (14.3) | 64 (14.2) | 375 (17.3) | 51 (14.1) | 9 (2.6) |

| Healthcare-based | 13,140 (85.9) | 402 (89.3) | 1,914 (88.1) | 313 (86.7) | 221 (64.4) |

| LARC | 1,847 (12.1) | 81 (18.0) | 486 (22.4) | 88 (24.4) | 13 (3.8) |

| Other | 3,498 (22.9) | 100 (22.2) | 455 (21.0) | 89 (24.7) | 21 (6.1) |

| None | 5,648 (36.9) | 152 (33.8) | 675 (31.1) | 135 (37.4) | 276 (80.5) |

Unadjusted frequencies, presented as n (%).

Nurses’ Health Study 2 (NHS2) participants were born 1947–1964 and Nurses’ Health Study 3 (NHS3) 1965–1995.

Barrier methods=male/female condom, diaphragm/cervical cap; Healthcare-based methods=oral contraceptives, shots, ring, patch; long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods=hormonal/non-hormonal intrauterine device (IUD), implant; Other methods=natural family planning, rhythm, foam/jelly/spermicide/sponge, withdrawal, tubal ligation, vasectomy, emergency contraception, other; None. Frequencies add up to more than 100% due to participants being able to report more than one method.

Ever use of healthcare-based methods was repeatedly assessed in NHS2 (1989, ‘91) and NHS3 (2010). Participants’ use of barrier, LARC, and other methods does not fully capture ever use because it was assessed only through reports of current use in particular questionnaire waves: NHS2 (biannually from 1989–2011) and NHS3 (2010).

Distributions of contraceptive methods use varied between sexual orientation groups, adjusted for potential confounders. Lesbians were the least likely of all sexual orientation groups to use any contraceptive method. In contrast, compared to completely heterosexual women with no same-sex partners, those who identified as completely heterosexual with same-sex partners, mostly heterosexual, or bisexual were generally more likely to use any method of contraception. We discuss these results in more detail below (see Table 3 for the aRRs and 95%CIs).

Table 3.

Probability of ever using contraceptive methods among female participants in the U.S.-based Nurses’ Healthy Study 2 and 31 by sexual orientation group.

| Risk Ratio2 (95%CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N=118,462 | Heterosexual (NHS2) or Completely Heterosexual with no same-sex partners (NHS3) | Completely Heterosexual with same-sex partners | Mostly Heterosexual | Bisexual | Lesbian |

| NHS2 (n=99,850) | (n=98,509, 98.7%) | (n=415, <1%) | (n=926, 0.9%) | ||

| Contraceptive Method3 | |||||

| Barrier | ref. | 0.99 (0.89, 1.11) | 0.33 (0.28, 0.39) | ||

| Healthcare-based | ref. | 0.97 (0.93, 1.01) | 0.77 (0.74, 0.81) | ||

| LARC | ref. | 1.01 (0.65, 1.57) | 0.10 (0.04, 0.26) | ||

| Other | ref. | 0.87 (0.81, 0.93) | 0.36 (0.32, 0.40) | ||

| None | ref. | 1.00 (0.91, 1.10) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.07) | ||

| NHS3 (n=18,612) | (n=15,288, 82.1%) | (n=450, 2.4%) | (n=2,171, 11.7%) | (n=361, 1.9%) | (n=342, 1.8%) |

| Contraceptive Method3 | |||||

| Barrier | ref. | 1.02 (0.81, 1.28) | 1.14 (1.04, 1.26) | 0.98 (0.76, 1.26) | 0.21 (0.11, 0.39) |

| Healthcare-based | ref. | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.76 (0.70, 0.82) |

| LARC | ref. | 1.48 (1.21, 1.81) | 1.82 (1.67, 1.99) | 2.01 (1.67, 2.42) | 0.32 (0.19, 0.55) |

| Other | ref. | 0.99 (0.81, 1.20) | 1.04 (0.94, 1.14) | 1.18 (0.96, 1.46) | 0.23 (0.15, 0.36) |

| None | ref. | 0.92 (0.79, 1.09) | 0.86 (0.79, 0.93) | 1.03 (0.87, 1.22) | 2.13 (1.89, 2.40) |

Nurses’ Health Study 2 (NHS2) participants were born 1947–1964 and Nurses’ Health Study 3 (NHS3) 1965–1995.

Adjusted for age and race. Multiple imputation was used during analyses for any missing covariate data. Models estimate the likelihood of using each contraceptive method vs all other methods (excluding none).

Barrier methods=male/female condom, diaphragm/cervical cap; Healthcare-based methods=oral contraceptives, shots, ring, patch; long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods=hormonal/non-hormonal intrauterine device (IUD), implant; Other methods=natural family planning, rhythm, foam/jelly/spermicide/sponge, withdrawal, tubal ligation, vasectomy, emergency contraception, other; None. Frequencies add up to more than 100% due to participants being able to report more than one method.

Lesbians in NHS2 were 90% less likely than heterosexuals to ever use LARCs (aRR [95%CI]: 0.10 [0.04, 0.26]). Results were similar for ever use of barrier methods (aRR [95%CI]: 0.33 [0.28, 0.39]) and ever use of other contraceptive methods (aRR [95%CI]: 0.36 [0.32, 0.40]. Results were also similar in the NHS3 cohort; for example, lesbians were more than twice as likely as heterosexual peers to have used none (aRR [95%CI]: 2.15 [1.89, 2.44]). Compared to the reference group of completely heterosexuals with no same-sex partners, those who identified as completely heterosexual with same-sex partners, mostly heterosexual, or bisexual were generally more likely to ever use any method of contraception. For example, NHS3 mostly heterosexual women were more likely to ever use barrier methods (aRR [95%CI]: 1.14 [1.04,1.26]. Use of LARCs was especially striking across sexual orientation groups with sexual minority groups—with the exception of lesbians—being more likely to use LARCs; as one illustration, NHS3 bisexuals were more than twice as likely to ever use LARCs (aRR [95% CI]: 2.01 [1.67, 2.42]).

Results were consistent after restricting the analysis to participants who had male sexual partners at some point in their lifetime. Results were also consistent after adjusting for sexual behavior (i.e., age at coitarche, number of sex partners) and modeling sexual orientation in different ways (e.g., ever reporting a sexual minority status). Results pertaining to other contraceptive methods were also consistent after excluding permanent methods. Models examining current use of each contraceptive method—as measured from the participant’s most recent questionnaire response—were conducted in both cohorts (see Table 4 for the aRRs and 95%CIs); and again, sexual orientation patterns for current use were similar to the ever use patterns. Results were also similar when contraceptive methods were categorized according to WHO’s tiered effectiveness chart, though using such categories did reveal that sexual minorities were more likely than heterosexuals to use Tier 4 methods (i.e., foam/jelly/spermicide/sponge, withdrawal); that pattern was not apparent when Tier 4 methods were combined with other methods (e.g., natural family planning; see Table 5 for the frequencies and Table 6 for the aRRs and 95%CIs).

Table 4.

Probability of currently using contraceptive methods among female participants in the U.S.-based Nurses’ Healthy Study 2 and 31 by sexual orientation group.

| Risk Ratio1 (95%CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N=118,462 | Heterosexual (NHS2) or Completely Heterosexual with no same-sex partners (NHS3) | Completely Heterosexual with same-sex partners | Mostly Heterosexual | Bisexual | Lesbian |

| NHS2 (n=99,850) | (n=98,509, 99%) | (n=415, <1%) | (n=926, 1%) | ||

| Contraceptive Method2 | |||||

| Barrier | ref. | 0.83 (0.21, 3.31) | NA | ||

| Healthcare-based | ref. | 0.69 (0.33, 1.45) | 0.52 (0.29, 0.95) | ||

| LARC | ref. | 1.72 (0.24, 12.32) | NA | ||

| Other | ref. | 0.69 (0.38, 1.24) | 0.23 (0.11, 0.46) | ||

| None | ref. | 0.99 (0.90, 1.10) | 1.01 (0.95, 1.08) | ||

| NHS3 (n=18,612) | (n=15,288, 82.1%) | (n=450, 2.4%) | (n=2,171, 11.7%) | (n=361, 1.9%) | (n=342, 1.8%) |

| Contraceptive Method2 | |||||

| Barrier | ref. | 1.01 (0.79, 1.30) | 1.14 (1.02, 1.28) | 0.97 (0.74, 1.28) | 0.20 (0.11, 0.39) |

| Healthcare-based | ref. | 1.04 (0.94, 1.14) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.07) | 1.00 (0.90, 1.12) | 0.75 (0.66, 0.86) |

| LARC | ref. | 1.48 (1.19, 1.85) | 1.82 (1.65, 2.01) | 1.99 (1.61, 2.46) | 0.32 (0.19, 0.55) |

| Other | ref. | 0.99 (0.81, 1.20) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.14) | 1.18 (0.96, 1.46) | 0.23 (0.15, 0.36) |

| None | ref. | 0.92 (0.79, 1.09) | 0.86 (0.79, 0.93) | 1.03 (0.87, 1.22) | 2.13 (1.89, 2.40) |

Adjusted for age and race. Multiple imputation was used during analyses for any missing covariate data. Models estimate the likelihood of using each contraceptive method vs all other methods (including no contraceptive use).

Barrier methods=male/female condom, diaphragm/cervical cap; Healthcare-based methods=oral contraceptives, shots, ring, patch; long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods=hormonal/non-hormonal intrauterine device (IUD), implant; Other methods=natural family planning, rhythm, foam/jelly/spermicide/sponge, withdrawal, tubal ligation, vasectomy, emergency contraception, other; None. Frequencies add up to more than 100% due to participants being able to report more than one method.

Table 5.

Frequency1 of ever using contraceptive methods, according to the World Health Organization’s tiered effectiveness, among female participants in the U.S.-based Nurses’ Healthy Study 2 and 32 by sexual orientation group.

| Total N=118,462 | Heterosexual (NHS2) or Completely Heterosexual with no same-sex partners (NHS3) | Completely Heterosexual with same-sex partners | Mostly Heterosexual | Bisexual | Lesbian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS2 (n=99,850) | (n=98,509, 98.7%) | (n=415, <1%) | (n=926, 0.9%) | ||

| Contraceptive Method3 ,4 | |||||

| Tier 1 | 60,416 (61.3) | 189 (45.5) | 135 (14.6) | ||

| Tier 2 | 86,633 (87.9) | 353 (85.1) | 629 (67.9) | ||

| Tier 3 | 42,371 (43.0) | 180 (43.4) | 125 (13.5) | ||

| Tier 4 | 16,045 (16.3) | 72 (17.4) | 53 (5.7) | ||

| None | 98,147 (99.6) | 414 (99.8) | 926 (100.0) | ||

| NHS3 (n=18,612) | (n=15,288, 82.1%) | (n=450, 2.4%) | (n=2,171, 11.7%) | (n=361, 1.9%) | (n=342, 1.8%) |

| Contraceptive Method3,4 | |||||

| Tier 1 | 4,455 (29.2) | 154 (34.2) | 770 (35.5) | 145 (40.2) | 21 (6.1) |

| Tier 2 | 13,140 (85.9) | 402 (89.3) | 1,914 (88.1) | 313 (86.7) | 221 (64.4) |

| Tier 3 | 2,474 (16.2) | 71 (15.8) | 436 (20.1) | 63 (17.5) | 9 (2.6) |

| Tier 4 | 55 (0.4) | 5 (1.1) | 14 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) |

| None | 5,648 (36.9) | 152 (33.8) | 675 (31.1) | 135 (37.4) | 276 (80.5) |

Unadjusted frequencies, presented as n (%).

Nurses’ Health Study 2 (NHS2) participants were born 1947–1964 and Nurses’ Health Study 3 (NHS3) 1965–1995.

Tier 1=hormonal/non-hormonal intrauterine device (IUD), implant, tubal ligation, vasectomy; Tier 2=oral contraceptives, shots, ring, patch; Tier 3=male/female condom, diaphragm/cervical cap, natural family planning, rhythm; Tier 4=foam/jelly/spermicide/sponge, withdrawal. Frequencies add up to more than 100% due to participants being able to report more than one method.

Ever use of tier 2 methods was repeatedly assessed in NHS2 (1989, ‘91) and NHS3 (2010). Participants’ use of the other tiers does not fully capture ever use because it was assessed only through reports of current use in particular questionnaire waves: NHS2 (biannually from 1989–2011) and NHS3 (2010).

Table 6.

Probability of ever using contraceptives methods, according to the World Health Organization’s tiered effectiveness, among female participants in the U.S.-based Nurses’ Healthy Study 2 and 31 by sexual orientation group.

| Risk Ratio2 (95%CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N=118,462 | Heterosexual (NHS2) or Completely Heterosexual with no same-sex partners (NHS3) | Completely Heterosexual with same-sex partners | Mostly Heterosexual | Bisexual | Lesbian |

| NHS2 (n=99,850) | (n=98,509, 98.7%) | (n=415, <1%) | (n=926, 0.9%) | ||

| Contraceptive Method3 | |||||

| Tier 1 | ref. | 0.74 (0.67, 0.82) | 0.24 (0.20, 0.28) | ||

| Tier 2 | ref. | 0.97 (0.93, 1.01) | 0.77 (0.74, 0.81) | ||

| Tier 3 | ref. | 1.02 (0.92, 1.12) | 0.33 (0.28, 0.39) | ||

| Tier 4 | ref. | 1.09 (0.88, 1.34) | 0.37 (0.29, 0.48) | ||

| None | ref. | 1.00 (0.91, 1.10) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.07) | ||

| NHS3 (n=18,612) | (n=15,288, 82.1%) | (n=450, 2.4%) | (n=2,171, 11.7%) | (n=361, 1.9%) | (n=342, 1.8%) |

| Contraceptive Method3 | |||||

| Tier 1 | ref. | 1.17 (1.03, 1.32) | 1.26 (1.19, 1.33) | 1.30 (1.16, 1.46) | 0.19 (0.13, 0.29) |

| Tier 2 | ref. | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.76 (0.70, 0.82) |

| Tier 3 | ref. | 0.99 (0.80, 1.23) | 1.17 (1.07, 1.28) | 1.06 (0.85, 1.33) | 0.18 (0.09, 0.34) |

| Tier 4 | ref. | 3.12 (1.26, 7.77) | 1.81 (1.00, 3.25) | 1.56 (0.38, 6.37) | 0.80 (0.11, 5.80) |

| None | ref. | 0.92 (0.79, 1.09) | 0.86 (0.79, 0.93) | 1.03 (0.87, 1.22) | 2.13 (1.89, 2.40) |

Nurses’ Health Study 2 (NHS2) participants were born 1947–1964 and Nurses’ Health Study 3 (NHS3) 1965–1995.

Adjusted for age and race. Multiple imputation was used during analyses for any missing covariate data. Models estimate the likelihood of using each contraceptive method vs all other methods (excluding none).

Tier 1=hormonal/non-hormonal intrauterine device (IUD), implant, tubal ligation, vasectomy; Tier 2=oral contraceptives, shots, ring, patch; Tier 3=male/female condom, diaphragm/cervical cap, natural family planning, rhythm; Tier 4=foam/jelly/spermicide/sponge, withdrawal. Frequencies add up to more than 100% due to participants being able to report more than one method.

4. DISCUSSION

While certain sexual minority subgroups (e.g., bisexuals) in this sample were more likely to use some contraceptive methods such as LARCs, lesbians were less likely to use any methods. These new findings offer further evidence from the largest study on this topic with more detailed information about contraception methods than prior studies. Choice of contraceptive method was similar to nationally representative data[28]. For example, the vast majority of our participants reported ever using a healthcare-based method such as oral contraceptives. As expected, this use increased as women aged and had more opportunities to use such methods. Future studies could examine these age/cohort differences in more detail. LARC use increased among our younger participants while older participants were more likely to rely on other methods such as vasectomy and tubal ligation. Our findings that LARC use is more common among all sexual minority women (except lesbians) compared to heterosexuals, is supported by similar findings from the HER Salt Lake Contraceptive Initiative[29] and recent evidence that sexual minority women report higher LARC knowledge than their heterosexual peers[30]. The few condom studies that have been able to examine sexual minority subgroups also reported similar method distribution; for example, bisexuals in another sample reported the highest condom use for anal sex and heterosexuals reported the highest use for vaginal sex while lesbians reported the lowest condom use for anal or vaginal sex[31].

The existing literature on contraceptive use among sexual minority women has been limited by methodological constraints. Generally, sexual minority women report less condom use than heterosexual peers[32]. Sexual minority women also report less use of any contraceptive method[33,34], and less use of oral contraceptives than their heterosexual peers[32,34,35]. Additionally, bisexual[1] and lesbian[36] women are more likely than heterosexual women to have ever used emergency contraception. Our results do not align with all these findings, in part due to samples having limited statistical power to detect sexual minority subgroup differences and sexual minority women being combined into a single category.

This sample included only nurses and was limited in terms of racial/ethnic diversity. Therefore, results may not generalize to other populations. However, the frequency of contraceptive use was similar to national representative data indicating that nurses do not dramatically differ. Assessing contraceptive use on an annual or a biennial basis made it challenging to collect data on use patterns in further detail (e.g., use with partners of different sexes). Additionally, measures of contraceptive use were not assessed identically across the two cohorts and we had to collapse methods into broad categories of interest rather than examining each one individually. We also lacked data on more detailed measures of sexual behavior other than coitarche and number of sexual partners; future studies should explore these and other potential mediators (e.g., health insurance status). While the NHS3 cohort included data on all three dimensions of sexual orientation (i.e., identity, same-sex partners, and same-sex attractions), the NHS2 cohort was limited to sexual orientation identity. However, this study has a number of strengths including the large, prospective study design made up of participants living across the United States. We were also able to leverage the detailed measures of sexual orientation to examine different dimensions of sexual orientation (i.e., attraction, identity, sex of sexual partners).

Our findings confirm that many sexual minority patients need contraceptive counseling. Healthcare providers should ensure they offer this counseling to patients in need, regardless of sexual orientation. This will help mitigate the risk of STIs and unintended pregnancies. It is imperative that providers do not make assumptions about patients’ sexual orientation, including about its various dimensions (e.g., attraction, identity, sex of sexual partners) and about how it may change over time. Providers must take care to not assume that patients with STIs or an unintended pregnancy are heterosexual. When taking a sexual history and giving contraceptive counseling, providers should also use cultural humility. For example, providers can demonstrate their listening skills by acknowledging a patient may not be a high risk for an unintended pregnancy when the patient reports having only female partners but the provider could still mention some of the non-contraceptive benefits of different methods. Furthermore, providers must also ensure that patients who are not regularly being seen for contraception-related reasons are brought into the healthcare system for preventive care.

Acknowledgements:

An abstract of this work was presented as an oral presentation at the American Public Health Association Annual Meeting and Exposition on November 3, 2015 in Chicago, Illinois and as a poster at the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology Annual Clinical and Research Meeting on April 4, 2016 in Toronto, Ontario. Dr. Charlton was supported by grant F32HD084000, Drs. Rosario and Austin by R01HD057368, and Dr. Austin by R01HD066963 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Charlton was additionally supported by grant MRSG CPHPS 130006 from the American Cancer Society, grant SHPRF9–18 from the Society of Family Planning, and the Aerosmith Endowment Fund for Prevention and Treatment of AIDS and HIV Infections at Boston Children’s Hospital. Dr. Gaskins was supported by K99ES026648 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Austin was additionally supported by grants T71MC00009 and T76MC00001 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration. The Nurses’ Health Study 2 was supported by UM1CA176726 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and the Nurses’ Health Study 3 was supported by grants R24ES028521 from the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, U01HL145386 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, and from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.

References

- [1].Tornello SL, Riskind RG, Patterson CJ. Sexual orientation and sexual and reproductive health among adolescent young women in the United States. J Adolesc Health 2014;54:160–8. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Saewyc EM, Bearinger LH, Blum RW, Resnick MD. Sexual intercourse, abuse and pregnancy among adolescent women: does sexual orientation make a difference? Fam Plann Perspect 1999;31:127–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Charlton BM, Corliss HL, Missmer SA, Rosario M, Spiegelman D, Austin SB. Sexual orientation differences in teen pregnancy and hormonal contraceptive use: an examination across 2 generations. Am J Obs Gynecol 2013;209:204 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Goodenow C, Szalacha LA, Robin LE, Westheimer K. Dimensions of sexual orientation and HIV-related risk among adolescent females: evidence from a statewide survey. Am J Public Heal 2008;98:1051–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Riskind RG, Tornello SL, Younger BC, Patterson CJ. Sexual identity, partner gender, and sexual health among adolescent girls in the United States. Am J Public Health 2014;104:1957–63. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Saewyc EM, Poon CS, Homma Y, Skay CL. Stigma management? The links between enacted stigma and teen pregnancy trends among gay, lesbian, and bisexual students in British Columbia. Can J Hum Sex 2008;17:123–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lindley LL, Walsemann KM. Sexual Orientation and Risk of Pregnancy Among New York City High-School Students. Am J Public Health 2015:e1–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [8].Oswalt SB, Wyatt TJ. Sexual health behaviors and sexual orientation in a U.S. national sample of college students. Arch Sex Behav 2013;42:1561–72. 10.1007/s10508-012-0066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Operario D, Gamarel KE, Grin BM, Lee JH, Kahler CW, Marshall BDL, et al. Sexual Minority Health Disparities in Adult Men and Women in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2010. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e27–34. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Charlton BM, Corliss HL, Missmer SA, Frazier AL, Rosario M, Kahn JA, et al. Reproductive health screening disparities and sexual orientation in a cohort study of U.S. adolescent and young adult females. J Adolesc Heal 2011;49:505–10. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Everett BG. Sexual orientation disparities in sexually transmitted infections: examining the intersection between sexual identity and sexual behavior. Arch Sex Behav 2013;42:225–36. 10.1007/s10508-012-9902-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lindley LL, Walsemann KM, Carter JW. Invisible and at risk: STDs among young adult sexual minority women in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2013;45:66–73. 10.1363/4506613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bailey J, Kavanagh J, Owen C, McLean K, Skinner C. Lesbians and cervical screening. Br J Gen Pr 2000;50:481–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Carroll NM. Optimal gynecologic and obstetric care for lesbians. Obs Gynecol 1999;93:611–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Diamant AL, Schuster MA, Lever J. Receipt of preventive health care services by lesbians. Am J Prev Med 2000;19:141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Charlton BM, Corliss HL, Missmer SA, Frazier AL, Rosario M, Kahn JA, et al. Influence of hormonal contraceptive use and health beliefs on sexual orientation disparities in Papanicolaou test use. Am J Public Health 2014;104:319–25. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hillard P, Berek J, Barss V, Al. E. Guidelines for women’s health care: A resource manual 2007.

- [18].Henderson JT, Harper CC, Gutin S, Saraiya M, Chapman J, Sawaya GF. Routine bimanual pelvic examinations: practices and beliefs of US obstetrician-gynecologists. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;208:109.e1–109.e7. 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Blake SM, Ledsky R, Lehman T, Goodenow C, Sawyer R, Hack T. Preventing sexual risk behaviors among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: the benefits of gay-sensitive HIV instruction in schools. Am J Public Heal 2001;91:940–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Robin L, Brener ND, Donahue SF, Hack T, Hale K, Goodenow C. Associations between health risk behaviors and opposite-, same-, and both-sex sexual partners in representative samples of Vermont and Massachusetts high school students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:349–55. doi:poa10148 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Saewyc E, Skay C, Richens K, Reis E, Poon C, Murphy A. Sexual orientation, sexual abuse, and HIV-risk behaviors among adolescents in the Pacific Northwest. Am J Public Heal 2006;96:1104–10. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bao Y, Bertoia ML, Lenart EB, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Speizer FE, et al. Origin, Methods, and Evolution of the Three Nurses’ Health Studies. Am J Public Health 2016;106:1573–81. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Field AE, Camargo CA Jr., Taylor CB, Berkey CS, Frazier AL, Gillman MW, et al. Overweight, weight concerns, and bulimic behaviors among girls and boys. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38:754–60. 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Case P, Austin SB, Hunter DJ, Willett WC, Malspeis S, Manson JE, et al. Disclosure of sexual orientation and behavior in the Nurses’ Health Study II: results from a pilot study. J Homosex 2006;51:13–31. 10.1300/J082v51n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Remafedi G, Resnick M, Blum R, Harris L. Demography of sexual orientation in adolescents. Pediatrics 1992;89:714–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].World Health Organization (WHO). Ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services - Guidance and recommendations 2014:26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Daniels K, Mosher WD, Jones J. Contraceptive Methods Women Have Ever Used: United States, 1982–2010 Number 1982;62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Everett BG, Sanders JN, Myers K, Geist C, Turok DK. One in three: challenging heteronormative assumptions in family planning health centers. Contraception 2018;98:270–4. 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hall KS, Ela E, Zochowski MK, Caldwell A, Moniz M, McAndrew L, et al. “I don’t know enough to feel comfortable using them:” Women’s knowledge of and perceived barriers to long-acting reversible contraceptives on a college campus. Contraception 2016;93:556–64. 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kerr DL, Ding K, Thompson AJ. A comparison of lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual female college undergraduate students on selected reproductive health screenings and sexual behaviors. Womens Health Issues 2013;23:e347–55. 10.1016/j.whi.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, et al. Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Related Behaviors Among Students in Grades 9–12 - United States and Selected Sites, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ 2016;65:1–202. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].McCauley HL, Dick RN, Tancredi DJ, Goldstein S, Blackburn S, Silverman JG, et al. Differences by sexual minority status in relationship abuse and sexual and reproductive health among adolescent females. J Adolesc Health 2014;55:652–8. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cochran S, Mays V, Bowen D, Gage S, Bybee D, Roberts S, et al. Cancer-related risk indicators and preventive screening behaviors among lesbians and bisexual women. Am J Public Health 2001;91:591–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Roberts SA, Dibble SL, Scanlon JL, Paul SM, Davids H. Differences in Risk Factors for Breast Cancer: Lesbian and Heterosexual Women. J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc 1998;2:93–101. 10.1023/B:JOLA.0000004051.82190.c9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lévesque S, Rodrigue C, Beaulieu-Prévost D, Blais M, Boislard M-A, Lévy JJ. Intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and reproductive health among university women. Can J Hum Sex 2016;25:9–20. 10.3138/cjhs.251-A5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]