Abstract

Motor neurons project axons from the hindbrain and spinal cord to muscle, where they induce myofibre contractions through neurotransmitter release at neuromuscular junctions. Studies of neuromuscular junction formation and homeostasis have been largely confined to in vivo models. In this study we have merged three powerful tools - pluripotent stem cells, optogenetics and microfabrication – and designed an open microdevice in which motor axons grow from a neural compartment containing embryonic stem cell-derived motor neurons and astrocytes through microchannels to form functional neuromuscular junctions with contractile myofibers in a separate compartment. Optogenetic entrainment of motor neurons in this reductionist neuromuscular circuit enhanced neuromuscular junction formation more than two-fold, mirroring the activity-dependence of synapse development in vivo. We incorporated an established motor neuron disease model into our system and found that coculture of motor neurons with SOD1G93A astrocytes resulted in denervation of the central compartment and diminished myofiber contractions, a phenotype which was rescued by the Receptor Interacting Serine/Threonine Kinase 1 (RIPK1) inhibitor Necrostatin. This coculture system replicates key aspects of nerve-muscle connectivity in vivo and represents a rapid and scalable alternative to animal models of neuromuscular function and disease.

Keywords: Embryonic stem cell, motor neuron, myofiber, microdevice, optogenetics

Introduction

The central nervous system (CNS) relays motor commands to skeletal muscle through motor neurons (MNs), specialised nerve cells located in the brainstem and spinal cord. The degeneration of MNs and their synaptic connections with muscle underlies several paralysing and often fatal neuromuscular diseases. Consequently, understanding nerve-muscle connectivity is key to developing medical interventions which preserve or restore vital motor functions in humans.

During embryonic development in vertebrates, MNs emerge from ventral progenitor domains in the caudal neural tube[1] and project axons into the surrounding mesenchyme[2]. Motor axon growth cones then navigate towards their specific target muscle in a series of binary pathway choices, guided by local positional cues [3]. As they approach their synaptic targets, the release of agrin and acetylcholine from motor axons induces a redistribution of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) on myofibres through interactions that involve the activation of the Lrp4/Musk/Rapsyn receptor complex on the postsynaptic side[4]. This leads to an alignment of postsynaptic AchR clusters with presynaptic sites, the exclusion of AchRs from areas not occupied by axonal contacts, and the formation of the postsynaptic specialisation at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ)[5]. As NMJs mature, they stabilise and increase in size, a process that is dependent on neural activity and cholinergic neurotransmission between motor axon and myofibre[6]. The outgrowth of peripheral motor axons and the establishment of NMJs are crucial steps in connecting the CNS to muscles throughout the body and is essential for motor functions such as locomotion, posture and breathing.

Loss of NMJ stability is an early pathological feature of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), a fatal adult-onset neurodegenerative disease caused by the selective degeneration of MNs. About 15-20% of all ALS cases are familial, and some of the most common genetic defects associated with ALS are point mutations in the superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1) gene[7]. The degenerative process caused by these mutations is characterised by retraction of motor axons from the NMJ, an event observed before the onset of MN cell death or clinical symptoms in both a case report of a human ALS patient and the SOD1G93A ALS mouse model[8]. The loss of motor innervation appears to be critical to the disease process, as stabilisation of NMJs with an anti-Musk antibody in vivo promotes MN survival and extends the life span of SOD1G93A mice[9]. Cell-cell interactions within the CNS can impact on the peripheral pathology and represent a key factor in ALS. MNs exposed to astrocytes (ACs) expressing a mutant SOD1 gene show accelerated disease progression in vivo[10], and co-culture of normal MNs with mutant SOD1-ACs induces MN degeneration[11]. This process is driven by the reactive state of ALS-related ACs and the soluble factors they release[12].

A key advance in modelling both normal MN biology and MN disease was the establishment of in vitro derivation protocols capable of generating large numbers (>106) of MNs from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs)[13]. These protocols use chemical cues that govern normal neurogenesis in the spinal cord and emulate the developmental program of MN specification, allowing the study of transcriptional programs of MN differentiation[14], cellular mechanisms of MN degeneration[15], and local spinal circuit formation[16]. Nevertheless, MNs in these models lack their normal functional context, because they are not connected to myofibres through NMJs.

In vitro co-cultures of primary MNs and myofibres have long been used to model neuromuscular circuits. An early culture system was established by Fischbach in the 1970s and consisted of spinal cord cells grown on a monolayer of myofibres[17]. Later formats included organotypic co-cultures of spinal cord slices and muscle[18], and MN/myofibre co-cultures in microfluidic devices[19]. Adapting these cell culture techniques, several groups developed PSC-MN/myofibre co-culture systems[20], and employed optogenetics to selectively control neural activity of MNs and myofiber contractions[21]. These reports have provided important insights into factors influencing NMJ stability, but unlike in vivo muscle, NMJs and myofibres were often intermixed with MN cell bodies, and 2D co-cultures typically lack a hydrogel scaffold that would stabilise myofibres during contractions.

Building on studies which showed that cultured myofibres can be stabilised by a combination of hydrogel embedding and attachments to artificial anchor points[22], Kamm and colleagues were able to model a neuromuscular circuit in microfluidic devices, where optogenetic MNs were co-cultured with myofibres[23]. These devices however lack miniaturisation, segregation of neural cell bodies and myofibres, and open access of cells to the medium. In this paper we address these issues and report the development of a PSC-based model of NMJ formation and neuromuscular disease. The device described here is more than 10-fold smaller, easier to manufacture, uses defined neural cell populations, allows optogenetic entrainment of NMJs, and direct quantification of myofibre contractions. MNs and ACs were derived separately from mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in vitro, purified, aggregated into 3D spheres and plated on an open tissue culture device. ESC-MNs projected axons through microchannels connecting the neural compartment with the myofiber compartment and formed NMJs with chick primary myofibres. This arrangement recapitulates the anatomical separation of the CNS and muscle in vivo. By using ESC-MNs that stably expressed the genetically encoded channelrhodopsin-2H134R (ChR2) photosensor[24], we were able to selectively elicit MN activity with blue light without mechanical interference. To validate our in vitro model, we sought to verify that it could emulate key features of neuromuscular circuits in vivo. First, we demonstrated that optogenetic entrainment promoted NMJ formation of ChR2-positive MNs, with markedly greater synapse formation compared to inactive controls. Secondly, we showed that MNs co-cultured with ALS-related SOD1G93A-ACs initially project normally to the myofibre compartment, but then display loss of axonal projections and reduced light-depended myofibre contractions. This deterioration of motor innervation resembles the early peripheral pathology of ALS seen in human patients and rodent models.

Results

Generation of stable co-cultures of optogenetic ESC-MNs and ESC-ACs

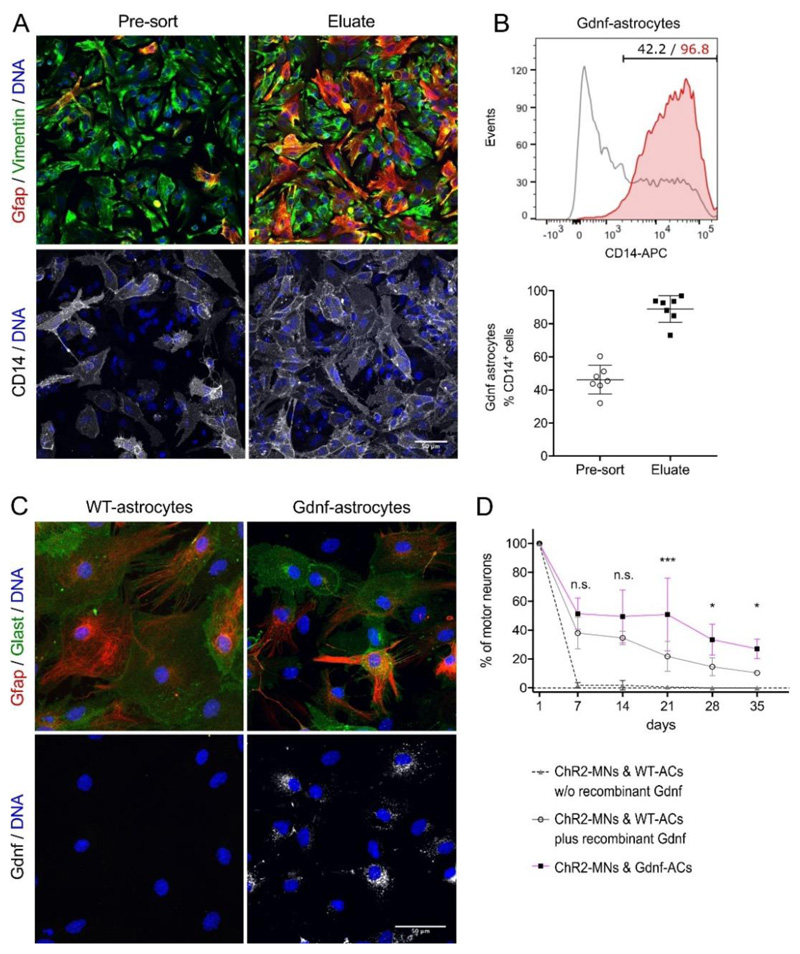

To generate a reliable source for enriched ESC-derived spinal-type MNs[25] and ACs[26] for the neural component of the neuromuscular model, we first optimised traditional ESC media compositions, culture conditions, and differentiation protocols (Figure S1, Supplemental Experimental Procedures). We also equipped the GFAP::CD14 AC reporter ESC clone (here referred to as WT, wild-type) with the ‘Glia-derived neurotrophic factor’[27] (Gdnf)-expressing CAG::Gdnf transgene to improve MN survival in MN/AC co-cultures. Gdnf-ACs were enriched by magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) (Figure 1A, B) using the CD14 cell-surface reporter and plated as a monolayer along with ChR2-MNs, which were MACS-enriched with the MN-specific Hb9::CD14-IRES-GFP reporter[25]. Gdnf expression in sorted Gdnf-ACs was confirmed by immunocytochemistry (Figure 1C) and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis (Table S1). Nearly all MNs died within 7 days when cultured on WT-ACs in the absence of neurotrophic support. In contrast, MNs co-cultured with Gdnf-ACs survived for 35 days in culture. The addition of recombinant Gdnf to co-cultures with WT-ACs promoted MN survival to a lesser extent than co-plating with Gdnf-ACs (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

ESC-ACs differentiated from GFAP::CD14/CAG::Gdnf ESCs. (A) Gdnf-AC cultures without and with anti-CD14 enrichment by MACS. Cells were labelled for the AC markers Gfap and Vimentin; scale bar 50μm. (B) Top: Representative flow cytometry analysis of anti-CD14-enriched ACs showing the percentage of ACs in differentiation cultures prior (black) and after (red) MACS. Bottom: AC enrichment was quantified in n=7 independent experiments. Lines indicate mean and SD, individual experiments are represented by points. (C) Gdnf detection in WT and Gdnf-ACs. Cell were labelled for the AC markers Gfap and Glast, and for Gdnf; scale bar 50μm. (D) Long term survival of motor neurons co-cultured with WT-ACs in medium without (dashed line) or with recombinant Gdnf (solid grey line) and Gdnf-ACs (magenta line) in medium without Gdnf (n=3, each experiment in triplicate).

From day 7 onwards all data points of ChR2-MN/WT-AC without recombinant Gdnf are significantly different from both other groups (not shown in the figure, p < 0.0001). Two-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, *** p<0.001, n.s. not significant (p > 0.05). Error bars indicate SD.

ChR2[24] is the most commonly used optogenetic actuator, and our group has previously characterised the electrophysiological properties of ESC-derived ChR2-MNs in vitro and demonstrated their ability to trigger muscle contractions in vivo[26]. However, orange-red light offers the advantage of better tissue penetration and lower phototoxicity over blue light. To identify an optimal optogenetic actuator for our model, we compared the properties of MNs expressing red-activatable channelrhodopsin (ReaChR)[28], a light-activated channel with optimal excitation in orange-red spectrum (λ ∼590-630 nm), with ChR2-expressing MNs.

Purified MNs expressing ChR2 or ReaChR (Figure S2) were co-cultured with Gdnf-ACs for up to 21 days, then whole-cell current-clamp recordings were performed to characterise MN maturation[20a, 29] and determine the suitability of optogenetic actuators. Both ChR2- and ReaChR-expressing MNs matured electrophysiologically over three weeks as expected of non-optogenetic ESC-MNs[20a] (Figure S3A-G). However, the relatively higher capacity of ChR2-MNs to fire sustained bursts of high frequency action potentials of larger amplitude (Figure S3H-J), and their faster recovery to resting membrane potential following cessation of light exposure (Figure S3K), engenders their greater suitability for our neuromuscular model.

In summary, we have optimized differentiation protocols for mouse ESC-derived MNs and ACs, established long term viable co-cultures of MN and ACs, and identified ChR2 as the more appropriate optogenetic actuator for MN stimulation. We next set out to engineer a co-culture platform to model the NMJ in vitro.

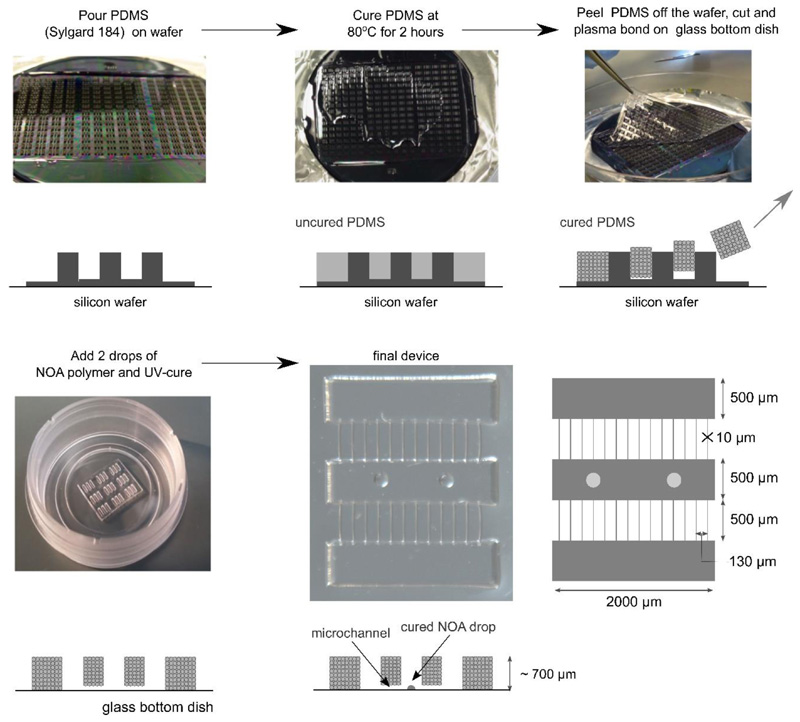

Assembly of neuromuscular circuits in compartmentalised tissue culture devices

The dimensions of the co-culture device (5 mm2) we designed are approximately 20-60 times smaller than those of other compartmentalised culture systems[23, 30] (ca. 100-300 mm2), which enabled us to mount an array of devices onto one plate (Figure 2) and perform several replicates in each culture. The device had one central myofibre compartment and two outer compartments for MN/AC aggregates, each 2 mm long and 500 μm wide; the compartments were linked by 500 μm long microchannels, 10 μm in width and height. The channels allowed motor axons to project through whilst maintaining separation of MN and myofibre cell bodies. The presence of two outer compartments provided the option to compare MN/AC aggregates with two different genotypes that project axons onto the same myofibre target in one device. We opted to produce open devices since it has been reported that neurons cultured in closed devices have a reduced survival time[31]. A silicon wafer mould was prepared by standard photolithography techniques. The devices were then fabricated by soft lithography[32] by pouring polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) over the wafer and curing it at 80°C. The cured PDMS was peeled off the wafer, cut into sections of 3x3 or 3x2 devices, and attached onto glass-bottom dishes by plasma bonding. The fabricated devices closely matched our design (Figure S4). We then manually added two drops of the photopolymer NOA-73 as anchor points for myofibres (Figure S5) to the bottom of the central compartment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Manufacturing procedure used to generate open microdevices. PDMS was poured and spread onto a silicon wafer. After curing, the PDMS replica was peeled off from the silicon wafer, cut into a smaller 3x3 (or 2x3) platform format, and plasma bonded to a glass substrate. NOA-73 drops of ca. 150-200μm diameter were added to the central compartment in register with microchannels four and nine, and cured with UV light.

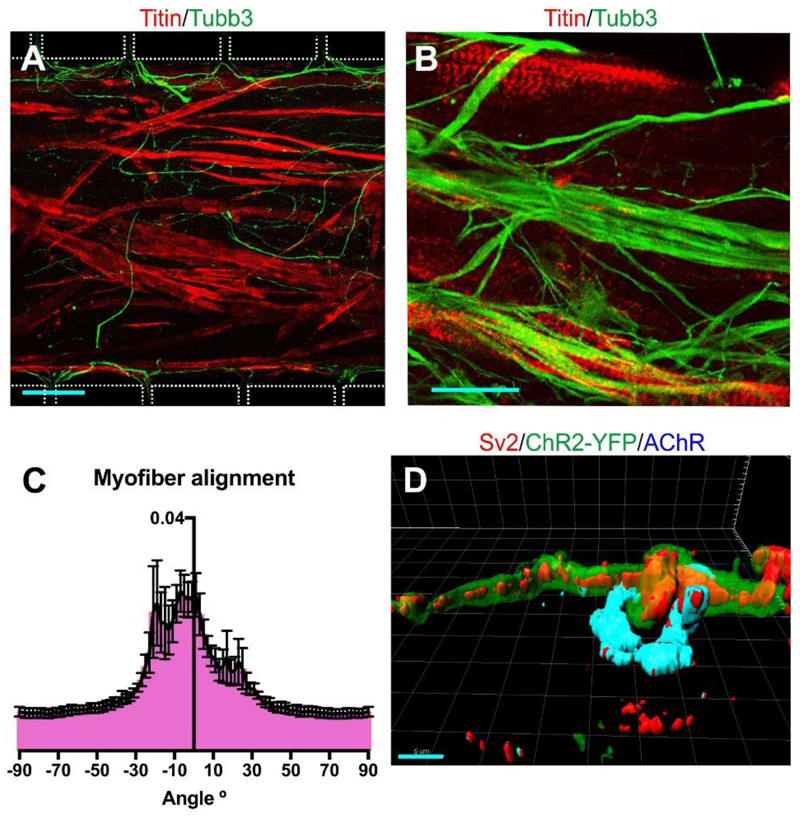

MACS-sorted MNs and ACs were clustered into 3D aggregates of 5000 cells per cell type prior to seeding in the device (Figure S6A). This ensured that equal numbers of cells were plated in the outer compartments and prevented the spill-over of single MNs into the myofibre compartment. Three MN/AC aggregates per outer compartment were plated in a fibrin/matrigel hydrogel to immobilise them during the subsequent handling of the device. The next day chick embryonic myoblasts were added to the bottom of the central compartment and embedded in a fibrin/matrigel hydrogel (Figure S6B). Chick myofibres were selected as the synaptic targets because they are known to form stable and functional NMJs with ESC-MNs[20]. The myoblasts fused and matured into a 3D sheet of striated myofibres (Figure 3A-B), held in place by the anchor points. The myofibres mostly aligned with the long axis of the central compartment (Figure 3C), and formed synaptic contacts with motor axons (Figure 3D) which morphologically resemble NMJs in vivo.

Figure 3.

Morphological analysis of myofibres. (A) Fused myofibres in the central compartment at day 9 were identified by Titin labelling; β3-tubulin labels motor axons. The outlines of the compartment boundaries and microchannels are shown as a white dotted line. Scale bar 100 μm (B) Titin staining of the cultured myofibres shows that they have matured and show striations. Scale bar 25 μm. (C) Myofibres preferentially align with the long axis of the central compartment (0° angle), as determined by Fourier analysis (n=6 z-stacks of different devices). Error bars indicate SD. (D) 3D-reconstruction of an in vitro NMJ. The sample was stained with antibodies to the pre-synaptic marker Sv2, YFP, and the postsynaptic marker AChR. Scale bar 5 μm.

Synapse formation in vitro is dependent on neural activity of MNs

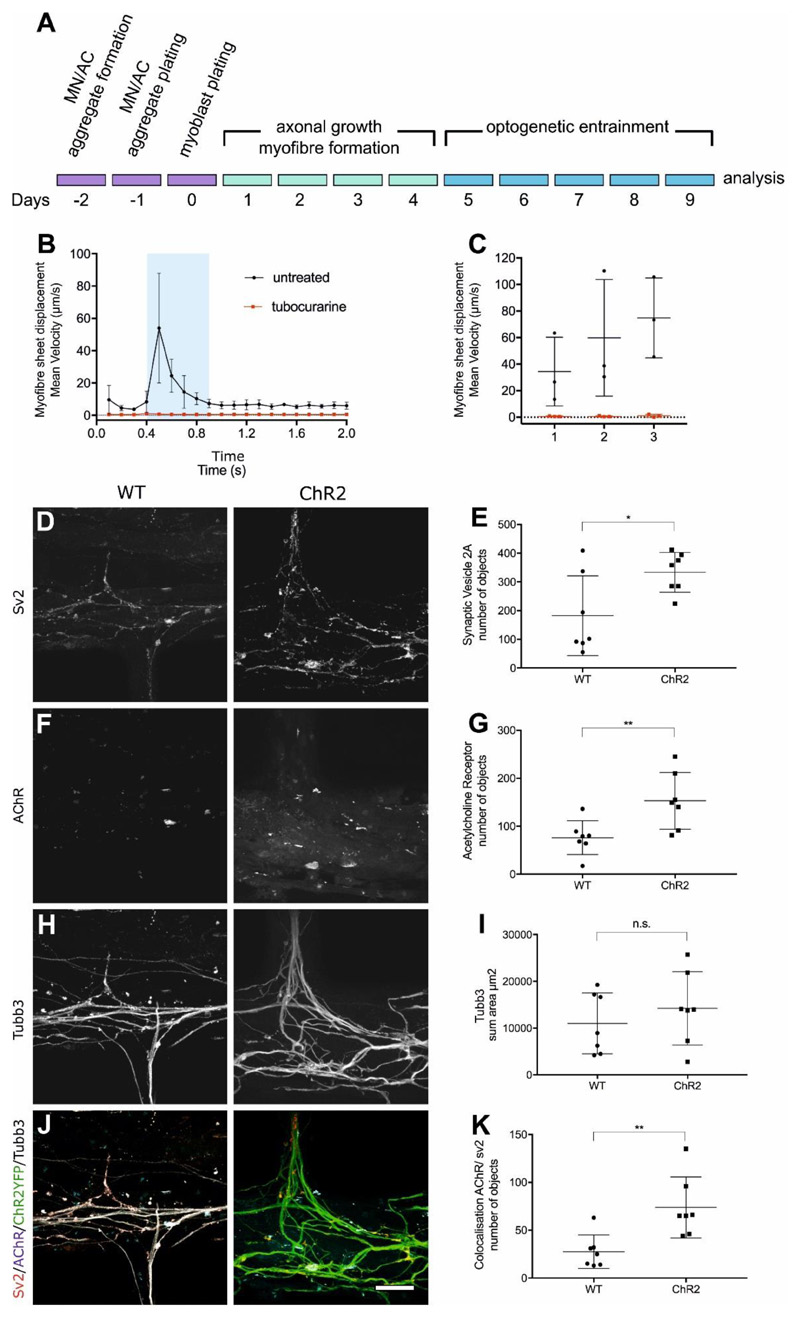

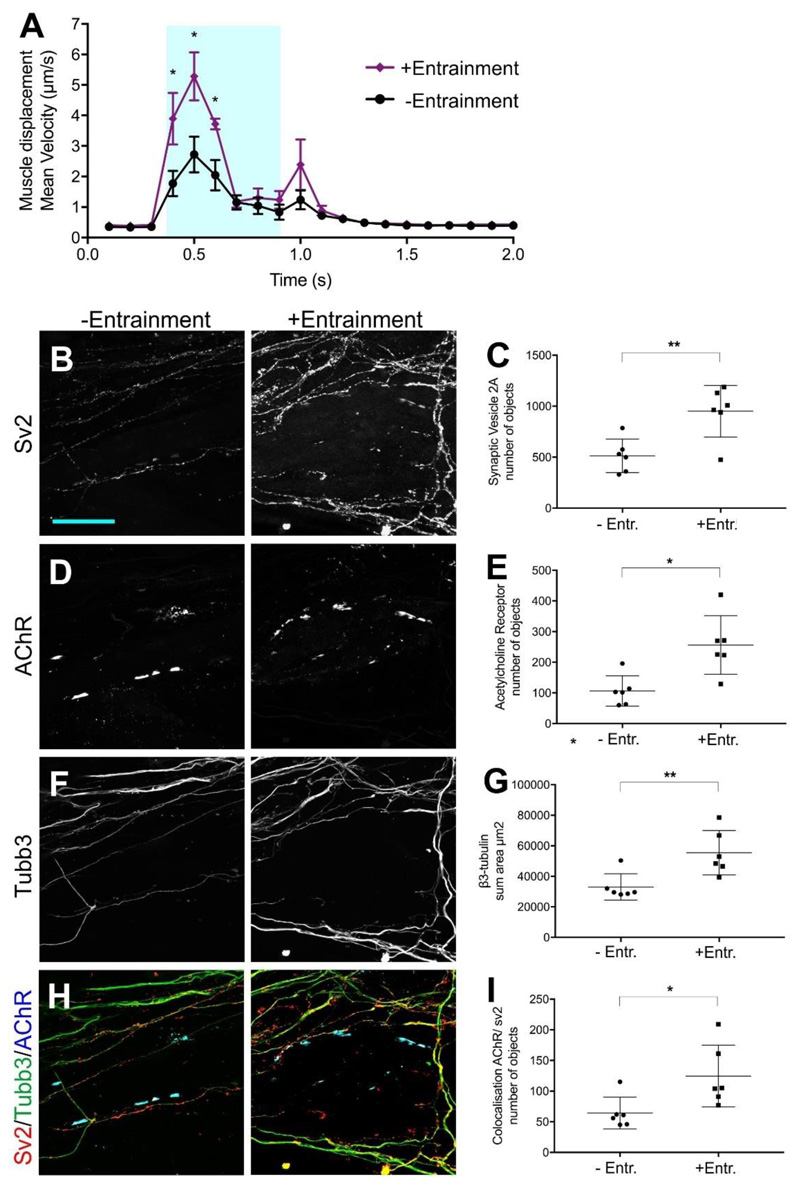

To investigate the impact of neural activity on NMJ formation in vitro, we plated light-responsive ChR2-MNs and light-insensitive WT-MNs, both aggregated with Gdnf-ACs, separately in the two outer compartments of the same device. One day later, myoblasts were seeded into the central compartment (Figure 4A). During the first few days of culture, ChR2-MNs and WT-MNs projected axons through the microchannels to contact myofibres. ChR2-MNs were entrained with blue light between day 5 and day 9 (1 hour/day at 5 Hz, 20 ms epoch). During the optical entrainment all cell types were subjected to the light stimulus. To determine if motor axons established functional connections with myofibres, we assessed the formation of synapses between optogenetically entrained ChR2-MNs and myofibres at day 9 of the co-culture by measuring myofibre contraction velocity in response to neuron activation using particle image velocimetry (PIV). The basic working principles of PIV consist in dividing an image into small pixel blocks, the size of which is determined by the users. The local displacement is then computed by comparing two consecutive images using correlation maximization methods. For each block on image (n), the algorithm finds the position of a block of pixels in image (n+1) that resembles most the initial one within some boundary limits around the original position. This approach thus enables to measure a displacement map with a controllable coarse grain approximation. The displacement is represented by a field of arrows, the size of which is proportional to the local displacement. PIV analysis was initially established with co-cultures containing ChR2-MNs only (Figure S7A-B, Videos S1 and S2), and then applied to devices with ChR2- and WT-MNs (Figure 4B, C).

Figure 4.

In vitro neuromuscular circuits assembled in a compartmentalised device. (A) Experimental design outline. (B) Myofibre contractions recorded in devices containing ChR2-MNs in one side and WT-MNs on the other side. Blue box represents a 500 ms light stimulation. Black and red lines represent cultures in medium without and with tubocurarine, respectively (n=3 measurements with separate devices were performed in triplicate); Error bars indicate SD. (C) Maximum mean displacement during light stimulation. x-axis: individual devices. (D-K) Analysis of synapse formation in response to neural activity: Representative confocal images and quantification of pre- and post-synaptic structures (D-E) Sv2 and (F-G) AChR. Presence of ChR2- and WT-motor axons was determined by total area of (H-I) β3-tubulin. Co-localisation between pre and post-synaptic markers (J-K) as determined by Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Measurements (number of objects, area and co-localisation) were obtained from volume rendering of 40 sections (1μm high x 126.77μm width x 126.77μm length) in the central compartment using Imaris software. Scale bar 50um. *p < 0.05, **p<0.01 Mann-Whitney U (n=7 z-stacks per condition). Lines indicate mean and SD.

The myofibre sheet was recorded for 2 seconds (100 milliseconds/frame) during which ChR2-MNs were activated by a 500-ms pulse of blue light (470 nm). Upon ChR2-MN light-driven stimulation, myofibres rapidly contracted and then slowly relaxed to a pre-stimulation state (Figure 4B). To test if the contraction was driven by synaptic transmission between ChR2-MN and myofibres, we re-stimulated the cultures in the presence of the competitive AChR antagonist, tubocurarine (Figure 4B, C), which completely blocked the myofibre displacement response to blue light. Likewise, the sodium channel inhibitor Tetrodotoxin blocked myofibre contractions induced by light-stimulation of ChR2-MNs (Figure S8).

We analysed the innervation of myofibres in the devices on day 9 to evaluate the effect of MN entrainment on NMJ formation. We were able to detect an increase of pre- (Figure 4D-E) and post-synaptic (Figure 4F-G) structures in association with ChR2-MNs. Whilst β3-tubulin+ axons from both ChR2- and WT-MNs extended through the microchannels and covered similar areas in the central myofibre compartment (Figure 4H-I), the number of synapses formed by ChR2-MNs onto myofibres was markedly higher than those formed by WT-MNs (Figure 4J-K).

We next addressed if enhancement of NMJ formation by optogenetic entrainment also increased the myofiber response. To this end, we loaded ChR2-MN/Gdnf-AC aggregates into both outer compartments and myofibres into the central compartment, and either exposed the devices to blue light stimulation (Figure 4A), or left them unstimulated for the entire culture period. Entrained cultures showed increased myofibre contractions in response to light (Figure 5A), as well as increased pre- (Figure 5B-C) and postsynaptic (Figure 5D-E) structures. In contrast to co-cultures of WT-MNs and ChR2-MNs in the same device (Figure 4H-I), entrained ChR2-MNs showed increased motor axon outgrowth compared to inactive ones (Figure 5F-G). Consistent with the previous experiment (Figure 4J-K), neural activity promoted NMJ formation (Figure 5H-I).

Figure 5.

Optogenetic entrainment enhances myofibre responses and NMJ formation of ChR2-MNs. (A) Myofibre contractions recorded on day 9 in devices +/- light entrainment between day 5 and day 9. Blue box represents a 500 ms light stimulation. Unpaired t test two-tailed p-value, *p<0.05. Error bars indicate SD (n=6 devices, three technical replicates per device) (B-I) Analysis of synapse formation in response to neural activity: Representative confocal images and quantification of pre- and post-synaptic structures (B-C) Sv2 and (D-E) AchR (BTX). Presence of non-entrained/entrained motor axons was determined by total area of (F-G) β3-tubulin. Co-localisation between pre and post-synaptic markers (H-I) as determined by Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Measurements (number of objects, area and co-localisation) were obtained from volume rendering of 40 sections (1μm high x 126.77μm width x 126.77μm length) in the central compartment using Imaris software. Scale bar 50um. *p < 0.01, **p<0.05 Mann-Whitney U (n=6 z-stacks per condition). Lines indicate mean and SD.

Taken together, these data indicate that optogenetic stimulation of ESC-MNs induced contractions of the myofibre sheet in the central compartment, a response that depended on cholinergic neurotransmission. Furthermore, optogenetic entrainment of ESC-MNs enhanced the number of synaptic contacts formed onto myofibres.

Co-culture of MNs with SOD1G93A-ACs causes denervation and reduced myofibre contractions

The early disease stages in the SOD1G93A rodent in vivo model of ALS are characterised by muscle weakness due to denervation[33]. Despite this, in vitro models of ALS typically focus on MN survival, measuring the endpoint of the disease[34], but not the preceding deterioration of muscle innervation and function. To determine if we could recapitulate ‘peripheral’ ALS phenotypes in our neuromuscular system, we exposed normal MNs to ACs expressing SOD1G93A. Such co-cultures are an established model for non-autonomous aspects of cellular degeneration in ALS[11].

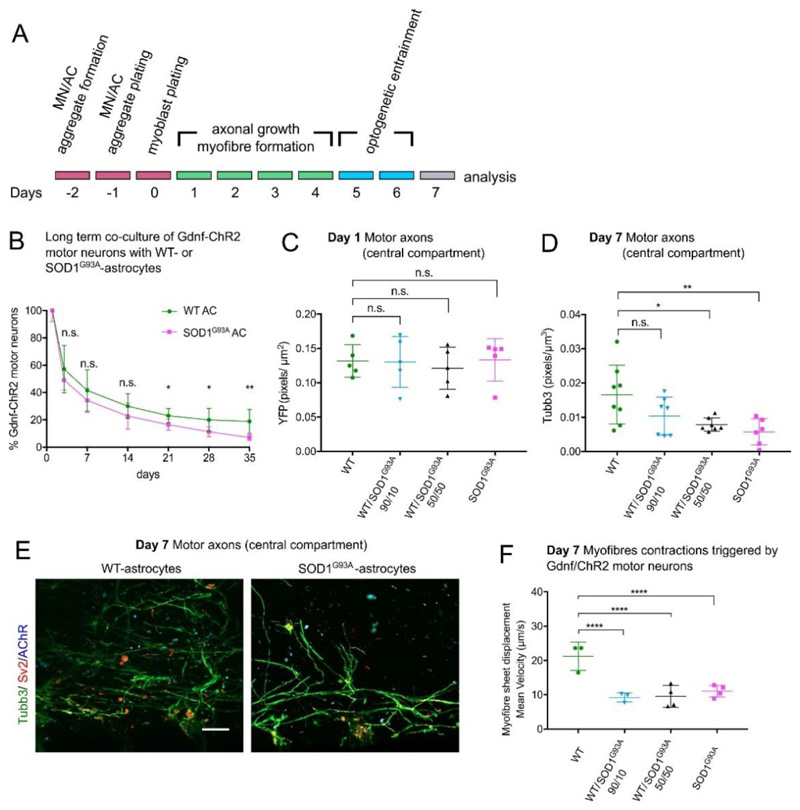

In ESC-ACs carrying the CAG::SOD1G93A transgene, the constitutive expression of human SOD1 is 1.4 times higher than endogenous mouse Sod1 (Table S1). Additionally, SOD1G93A-ACs contained more Ubiquitin-positive cytoplasmatic inclusions than WT-AC controls (Figure S9). Such inclusions are a pathological feature of ACs in mutant SOD1 models of ALS[35]. Since the SOD1G93A-ACs do not express Gdnf, which is required for MN survival (Figure 1D), we employed ChR2-MNs which also carry the CAG::Gdnf transgene[26]. We first evaluated the survival of Gdnf/ChR2-MNs in 2D co-cultures with WT-ACs or SOD1G93A-ACs. Up to day 14 there was no significant difference in the survival rate of Gdnf/ChR2-MNs co-cultured with either WT- or SOD1G93A-ACs. However, from day 21 until day 35 the survival rate of MNs co-cultured with SOD1G93A-ACs was significantly lower compared to co-cultures with WT-ACs (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Effect of SOD1G93A-ACs on neuromuscular circuits formation. (A) Experimental design outline. (B) Long term viability of Gdnf/ChR2-MNs co-cultured with WT- or SOD1G93A-ACs (n=3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate). MN viability decline is statistically significant different after day 14. Multiple t tests, one unpaired t test per time point, two-tailed p-value. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. n.s. not significant. Error bars indicate SD. (C) Axons present in the central compartment on day 1 quantified by the amount of YFP pixels per area. All culture conditions were equally permissive to initial axonal growth via microchannels towards myofibres (n=5 images); ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. (D) At day 7, there was a significant decline of axons detected in the myofibre compartment in MN co-cultures containing 100% or 50% SOD1G93A-ACs. There is no statistical difference between the MN co-cultured with 100% WT-ACs and 10% SOD1G93A-ACs; (100% WT-AC: n=8; 100% SOD1G93A-ACs: n=6; n=7 for the two other conditions) ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test, *p<0.05, **p<0.005. (E) Representative confocal images of the axons present in the myofibre compartment of Gdnf/ChR2-MNs co-cultured with 100% WT- or 100% SOD1G93A-ACs. Scale bar 50μm. (F) Myofibre contraction recorded in devices containing Gdnf/ChR2-MNs co-cultured with WT-ACs and/or SOD1G93A-ACs. Maximum mean displacement during light stimulation. We performed n=3 measurements (100%WT-ACs, 10%SOD1G93A-ACs) or n=4 measurements (50%SOD1G93A-ACs, 100%SOD1G93A-ACs) with separate devices, each of them in triplicate. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test, ****p<0.0001. Lines indicate mean and SD.

We aggregated Gdnf/ChR2-MNs with WT- and/or SOD1G93A-ACs mixed at different ratios (100/0, 90/10, 50/50, 0/100) to test if we could titrate the toxic effect of SOD1G93A. MN/AC aggregates and myoblasts were loaded into device as before (Figure 6A). On day 1, MNs exposed to WT- and/or SOD1G93A-ACs extended axons through the channels and contacted myofibres. We found no difference in motor axons extending into the myofibre compartment between MNs associated with ACs of the two genotypes (Figure 6C; Figure S10A). On days 5 and 6 Gdnf/ChR2-MNs were optically entrained for 1h/day (5 Hz, 20 ms epoch). By day 7 the 50% and 100% SOD1G93A-AC conditions exhibited reduced motor axon innervation of the central compartment compared to the WT-AC control (Figure 6D). Interestingly, there was no significant difference in axonal outgrowth between cultures containing only WT-ACs and those with 10% SOD1G93A-ACs (Figure 6D).

We measured myofibre contractions on day 7, rather than day 9 as previously (Figure 4), because the viability of MNs exposed to SOD1G93A-ACs deteriorates with time (Figure 6B), and motor axons had formed NMJs by day 7 (Figure 6E). Myofibre contractions were triggered by stimulating Gdnf/ChR2-MNs with a 500 ms light pulse. Myofibre velocity was significantly reduced in all cultures containing SOD1G93A-ACs compared to those with 100% WT-ACs (Figure 6F, Figure S10B-E). Thus, by using myofibre displacement as an indirect measurement of synapse function, we were able to capture subtle denervation in the 10% SOD1G93A-ACs condition, which was not evident by immunocytochemistry.

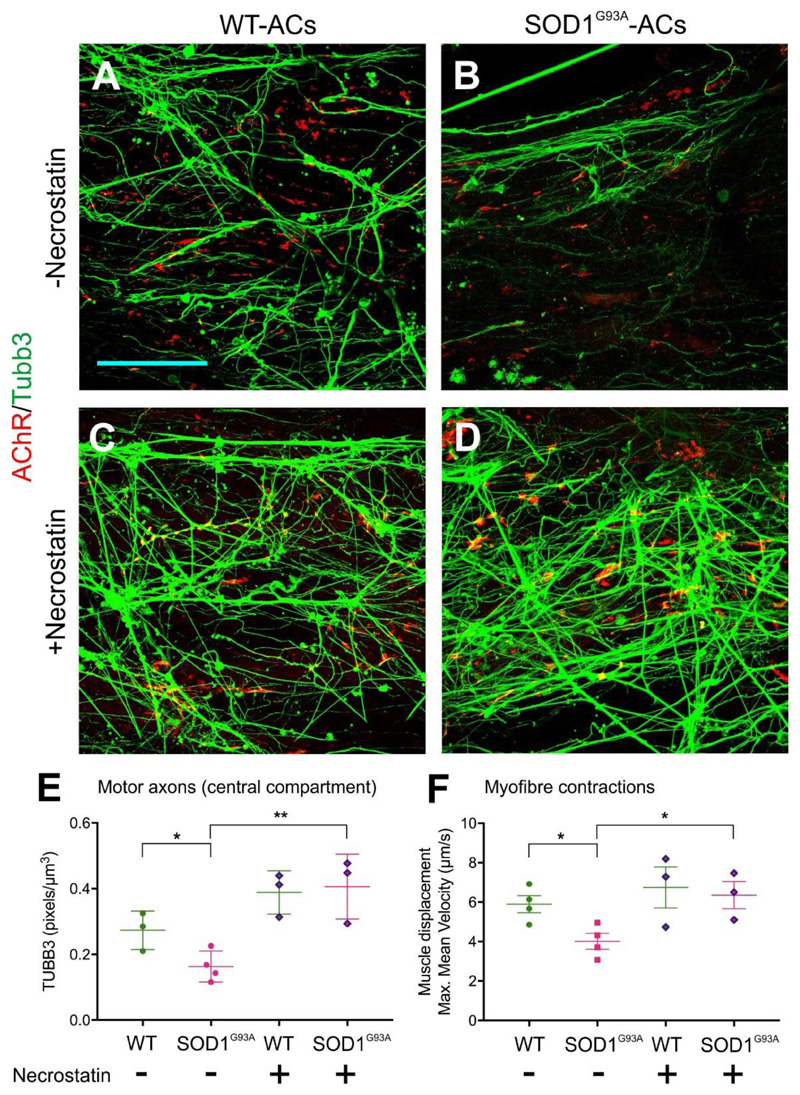

We next tested if this in vitro model is in principle suitable to determine the activity of candidate drugs. We co-cultured ChR2-MNs with WT- or SOD1G93A-ACs, each mixed 50:50 with Gdnf-ACs to provide neurotrophic support. Consistent with the previous experiment (Figure 6), the presence of SOD1G93A-ACs in aggregates resulted in axonal denervation (Figure 7A-B, 7E) and diminished myofiber contractions (Figure 7F) compared to WT-AC controls. Addition of the RIPK1 inhibitor Necrostatin, which has been previously shown to improve MN survival in an in vitro model of ALS[36], completely rescued both the axon outgrowth (Figure 7C-D, 7E) and the myofiber contraction phenotypes in co-cultures containing SOD1G93A-ACs (Figure 7F).

Figure 7.

Necrostatin rescues MN dysfunction caused by SOD1G93A-ACs. (A-D) Representative confocal images of the axons present in the myofiber compartment. ChR2-MNs were co-cultured with WT- or SOD1G93A-ACs in the absence or presence of Necrostatin. Scale bar 100μm (E) Axons are reduced in the myofibre compartment in MN co-cultures containing SOD1G93A-ACs compared to those containing WT-ACs. This decline was rescued by the addition of Necrostatin to the culture medium. (WT-AC: n=3; SOD1G93A-ACs: n=4; WT-AC +Necrostatin: n=3; SOD1G93A-ACs +Necrostatin: n=3 devices) Unpaired t-test, two-tailed p-value, *p<0.05; **p<0.01 (F) Myofibre contraction recorded in devices containing ChR2-MNs co-cultured with WT-ACs or SOD1G93A-ACs. Maximum mean displacement during light stimulation. We performed n=4 measurements (WT-ACs, SOD1G93A-ACs) or n=3 measurements (WT-ACs +Necrostatin, SOD1G93A-ACs +Necrostatin) with separate devices, each of them in triplicate. Unpaired t-test, two-tailed p-value, *p<0.05. Lines indicate mean and SD.

These observations indicate that the neuromuscular circuit model reported here is suitable for capturing 'peripheral' ALS-related phenotypes of motor axon-myofibre connectivity, caused by the ‘CNS-like’ interactions of MN cell bodies with SOD1G93A-ACs. Furthermore, we have provided proof-of-principle that the model can be used to test the effect of candidate ALS drugs.

Discussion

The CNS controls all motor functions through NMJs, specialised synapses between MNs and myofibres. An in vitro model of nerve-muscle communication could accelerate the discovery of mechanisms underlying NMJ formation and dysfunction. So far developing an accurate model has posed several challenges. These include ensuring defined cellular identities and genotypes, segregation of neural cell bodies and myofibres into ‘CNS-like’ and ‘peripheral’ areas, control over neural activity patterns, and stabilisation of contractile myofibres. To address these challenges, we developed a model of neuromuscular circuitry that co-cultures - in an open, compartmentalised device - neural aggregates (containing mouse ESC-derived MNs and ACs) with primary myofibres, connected by motor axons that form bona-fide NMJs. As proof-of-principle that this model recapitulates key features of neuromuscular circuits in vivo, we showed that NMJ formation was enhanced by optogenetic entrainment of MNs, and that co-culture of MNs with ALS-related SOD1G93A ACs caused denervation and loss of neural control of myofibre contractions.

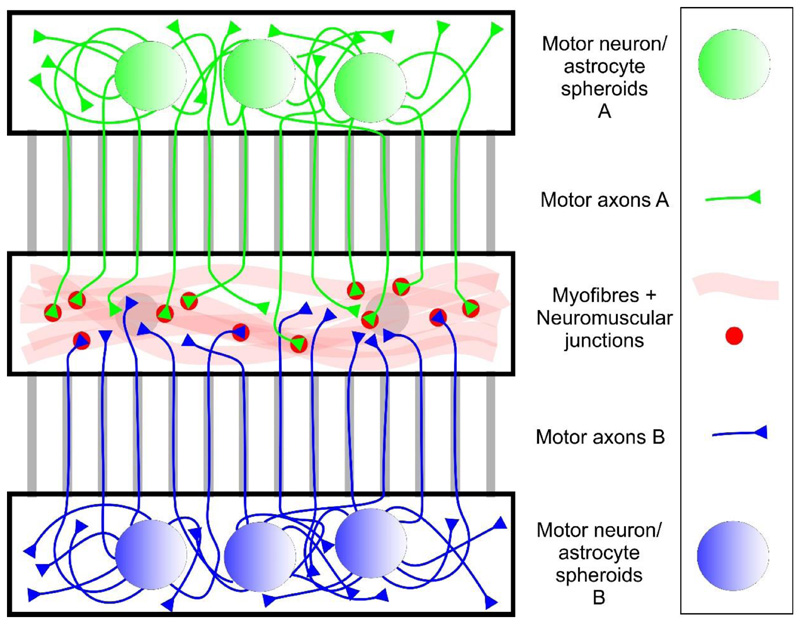

Compartmentalised tissue culture devices impose a defined microenvironment onto cultured neurons and have been used to investigate axon-specific targeting of mRNAs[30], the response of neurons and their progenitors to graded chemical cues[37] and connectivity between different types of neurons[38]. However, in order to accommodate myofibres as synaptic targets of MNs in such devices, their design has to be modified to emulate in vivo muscle, as contractile myofibres will detach and collapse when cultured on a rigid surface[39]. First, myofibres must be embedded in a hydrogel scaffold, which mimics muscle extracellular matrix and promotes muscle maturation[40], and secondly, these myofibre constructs then have to be attached to anchor points, which serve as the equivalent to tendons and keep them suspended[22]. Uzel and colleagues[23a] were the first to insert such a myofibre construct, held in place between flexible cantilevers, into a microfluidic device. Their device also includes a second, connected compartment for seeding embryoid bodies (EBs) which contained optogenetic ESC-derived MNs. The MNs formed NMJs with myofibres and induced light-dependent contractions, measured as cantilever deflection. In our study, we followed the same basic concept and designed a new device (Figure 8) which offers several advantages and innovative features:

-

1)

Motor axons are guided to the myofibre compartment by microchannels which act as mechanical cues and bring more axons into contact with their targets.

-

2)

The device is a simple and scalable design, made up of a one-part PDMS construct. This allows us to perform multiple replicates in each culture and lends itself towards drug screening assays.

-

3)

The device is open, not microfluidic, so the compartments can be loaded directly and the cells are fully exposed to oxygen and nutrients[31].

-

4)

Motor axon and myofibres are located close to the glass bottom of the plate, and the hydrogel-embedded myofibre sheet is held in place by flat dome-shaped anchor points. This allows us to directly image it and quantify contractions by PIV.

-

5)

We use CNS-like 3D aggregates of sorted MNs and ACs, not EBs, and thus control cell types, cell ratios, and individual genotypes in the neural compartment.

Figure 8.

In vitro model of a neuromuscular circuit in an open microdevice. In the scheme shown here, MNs of two different genotypes are plated separately into the two outer compartments, allowing for the direct comparison of NMJ formation by their motor axons (green and blue) in the central myofiber compartment. An example for this approach (with ChR2-positive and -negative MNs) is shown in Figure 4.

Neuronal activity plays an important role in the development and maturation of neuronal circuits in the brain[41]. Both in vivo and in vitro work have emphasised the importance of local (rather than global) modulation of activity, where differences in the activity between neurons drive competition for synaptic space[42]. Likewise, NMJ maturation has been shown rely on the coordinated activity of MNs, as mouse mutants deficient in genes involved in cholinergic neurotransmission show defects in NMJ maturation, homeostasis and competitive refinement during development[6]. We have shown that in our neuromuscular circuit model, the emergence of pre- and post-synaptic NMJ structures and, crucially, the alignment and coordination of these structures is dependent on optogenetic entrainment of MNs.

We noticed one discrepancy in the responses of inactive vs. active MNs: When inactive MNs were co-cultured with active ones in the same device, axon outgrowth did not differ significantly, whereas inactive MNs showed reduced axon outgrowth when cultured in a different device. This observation may be explained by direct or indirect interactions between the two MN populations, for example through chemotropic effects of the neurotransmitter[43], or increased release of neurotrophic factors by active motor circuits[44].

We were able to tightly control MN activity by loading MN/AC aggregates, rather than EBs, into the neural compartments. Whereas MNs in mixed EB cultures are spontaneously electrically active[20a] - likely driven by excitatory inputs from contaminating glutamatergic interneurons[13, 16] -, MNs in defined MN/AC co-cultures show minimal non-evoked activity[26]. As a result, optogenetic entrainment of ChR2-positive and -negative MNs allowed us to directly compare active and inactive neuronal populations in the same device. Given this technical advantage, we anticipate that the neuromuscular circuit model reported here may be used to expand on the seminal studies that described the basic principles of NMJ formation and the competitive refinement of MN axons as they mature.

We have also demonstrated the capacity of this system for modelling NMJ pathophysiology. To do this we co-cultured ESC-MNs with ESC-ACs carrying an ALS-linked SOD1G93A mutation. In this co-culture we observed denervation of myofibers and reduced muscle contraction, mimicking key features of the disease in humans. We were able to titrate the detrimental effect of SOD1G93A by changing the ratio of WT- and SOD1G93A-ACs. The device culture format enabled us to precisely quantify the reduced contractile response triggered by MNs whose cell bodies are exposed to SOD1G93A-ACs, a phenotype which we could rescue with the candidate ALS drug Necrostatin[36]. These observations mirror NMJ degeneration in mutant SOD1 mice[8, 45] albeit on a condensed time scale. To our knowledge, this study is the first to show an in vivo-like sequence of normal axon outgrowth followed by denervation in an in vitro model of ALS. Our observations on reduced myofiber contractions are similar to those made by Osaki et al.[23b] in a device-based co-culture model of ALS with human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-motor neurons carrying a mutant TARDBP gene.

Given the amenability of cells in our model to the introduction of genetic probes and imaging techniques, other aspects of the peripheral pathology in the distal axon and NMJ, such as defective axonal transport and protein aggregation, could be explored with our experimental system. For example, live imaging with pre- and post-synaptic fluorescent markers would enable us to measure the dynamics of NMJ denervation in an ALS model, and not just the end point of the process. In future studies, a closer approximation to ALS in humans will require several refinements, in particular the differentiation of MNs, ACs and myofibres from human patient-derived iPSCs and isogenic controls, longer-term cultures (>1 month) to account for the slow disease progression in human patients. We plan to incorporate 3D-myofibre constructs assembled with iPSC-myoblasts in a fibrin-based hydrogel, similar to the ones recently described by Bursac and colleagues[46]. A further step towards more complex neuromuscular circuits would be the inclusion of additional cell types relevant to ALS, such as terminal Schwann cells present at the NMJ in vivo. The applications of this system are not limited to ALS, and it could be adapted to model other familial diseases affecting neuromuscular circuits, such as Spinal Muscular Atrophy and muscular channelopathies.

Experimental Procedures

For details about the Experimental Section, see the Supporting Information.

Compartmentalised device fabrication

The coculture devices were fabricated by soft lithography[32], i.e. casting polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) on a silicon mould. From the cured PDMS sheet, rectangles containing six or nine devices were cut and attached to a glass bottom culture dish by plasma bonding. Then, two drops of the photopolymer NOA-73 were applied to the bottom of the central compartment and cured by UV exposure. Prior to plating of the cells, the devices were coated with Matrigel diluted 1:100 in Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM).

Generation of transgenic ESC clones

Mouse ESC clones carrying MACS-sortable Hb9::CD14-IRES-GFP (MN) and GFAP::CD14 (AC) reporter transgenes, as well as the Hb9::CD14-IRES-GFP/CAG::ChR2-YFP and Hb9::CD14-IRES-GFP/CAG::ChR2-YFP/CAG::Gdnf subclones, have been described previously[25–26]. From the parental ESC clones, we generated stably transfected MN reporter subclones carrying the CAG::ReaChR-YFP transgenes, and AC reporter subclones carrying either CAG::Gdnf or CAG::SOD1G93A transgenes.

Cell culture and differentiation

Mouse ESCs were cultured and differentiated as described [25–26] with some modifications (see Supporting Information). Differentiated neural cells were MACS-sorted with anti-CD14 antibody on day 5 (ESC-MNs) or day 12 (ESC-ACs) of culture. Pectoralis muscle was dissected from E12 chick embryos, and then dissociated to isolate primary chick myoblasts.

Electrophysiology

Whole cell patch clamp recordings were obtained from ESC-MNs stably expressing either ChR2 or ReaChR and cultured on a monolayer of Gdnf-expressing ESC-ACs for 7 and 21 days.

In vitro co-culture of MNs, ACs and myoblasts

Aggregates of MACS-sorted ESC-MNs and ESC-ACs (5000 each per aggregate) were plated into the outer chambers of the compartmentalised devices (Figure 2, Figure S6) and then immobilised in a fibrin/Matrigel hydrogel. The next day, 1000-2500 primary chick myoblasts were plated into the central compartment and embedded in a fibrin/Matrigel hydrogel. The cocultures were cultured for four days and then optically entrained (1 hour/day, 20 ms pulse at 5 Hz)[47] for the next five (Figures 4, 5) or two (Figures 6, 7) days. Myofibre contractions in response to light stimulation were recorded on day 9 (Figure 4, 5) or day 7 (Figure 6, 7).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Expression levels of Gdnf, mouse Sod1, human SOD1 and Gapdh were determined by qPCR (Table S1) at the at the Genomics Centre (KCL) or the Centre for Stem Cells & Regenerative Medicine (KCL).

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry of cultured cells was performed as described previously[25], and images acquired with a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM710 and LSM800, Nikon A1R) or an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus X73). Images were analysed with ImageJ software and Bitplane Imaris 9.1.2. All antibodies used in this study are listed in Table S2.

Colocalisation analysis of pre- and postsynaptic structures

NMJs and axons were labelled by immunohistochemistry with antibodies to Sv2, AChR (or BTX) and β3-tubulin, z-stacks of images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal microscope and analysed with the Bitplane Imaris 9.1.2 software.

Time-lapse Imaging

Myofibre contractions were induced by optogenetic stimulation at 470nm with a CoolLED illumination system and recorded by brightfield time-lapse imaging with an inverted Olympus IX71 epifluorescence microscope. Myofibre contraction velocity was quantified by PIV using the PIVlab package within Matlab (Mathworks).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out in GraphPad Prism or R. Information on statistical tests used for all experiments is shown in the Figure legends and in Table S3 (Supporting Information).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

C.B.M., P.P., V.V., and I.L. contributed equally to this work. Personnel and work were supported by the Medical Research Council (Grant No. MR/N025865/1, I.L.). Additional funding was provided by King’s Health Partners (Grant No. R130577, I.L.) and the Thierry Latran Foundation (OptiMus, J. Barney Bryson, Linda Greensmith and I.L.). P.P. was supported by a joint NUS/KCL PhD programme scholarship, P.H. by a Wellcome Trust “Cell Therapies & Regenerative Medicine” PhD studentship, V.G.S. and S.H. by a KCL Developmental Neurobiology PhD studentship,, and M.R. by a NC3Rs Training fellowship (Grant No. NC/P002420/1). J.B. is a Wellcome Trust Investigator. V.V. acknowledges seed funding from the Mechanobiology Institute at NUS. The work was supported by the Medical Research Council Centre grant (Grant No. MR/N026063/1). The authors acknowledge financial support from the Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre award to Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London and King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The authors thank Fiona M. Watt for support and encouragement and Anna Rose for expert technical support; Gianluca Grenci, Mona Suryana, and Sree Vaishanvi from the MBI microfabrication facility for their help in fabricating the wafers; Deniz Kent for advice on high content analysis; Queelim Ch’ng, Fiona Watt, Mukul Tewary, and Geraldine Jowett for comments on the manuscript; and Koichi Kawakami, Austin Smith, and Malcolm J. Fraser for providing reagents. C.B.M., P.P., D.C.S., P.H., and I.L. cultured and differentiated ESC clones. C.B.M., D.C.S., and I.L. established and characterized recombinant ESC clones. M.R. and J.B. planned electrophysiology experiments, and M.R. performed patch clamp recordings. V.G.S. recorded videos of myofibre contractions. C.B.M., P.H., S.H., and P.P. analyzed imaging data, and M.R. analysed electrophysiology data. V.V. designed the tissue culture devices, and P.P. and S.H. manufactured the devices. A.L. wrote software, and A.L. and C.B.M. build optoelectronic hardware. C.B.M., P.P., P.H., M.R., J.B., V.V., and I.L. wrote the manuscript and assembled the figures. V.V. and I.L. developed the original concept, designed, and oversaw the study.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Contributor Information

Dr Carolina Barcellos Machado, Centre for Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine, King’s College London, London SE1 9RT, UK; Centre for Developmental Neurobiology/MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King’s College London, London SE1 1UL, UK.

Dr Perrine Pluchon, Centre for Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine, King’s College London, London SE1 9RT, UK; Centre for Developmental Neurobiology/MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King’s College London, London SE1 1UL, UK; Mechanobiology Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117411.

Mr Peter Harley, Centre for Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine, King’s College London, London SE1 9RT, UK; Centre for Developmental Neurobiology/MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King’s College London, London SE1 1UL, UK.

Ms Victoria Gonzalez Sabater, Centre for Developmental Neurobiology/MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King’s College London, London SE1 1UL, UK.

Dr Danielle C. Stevenson, Centre for Developmental Neurobiology, King’s College London, London SE1 1UL, UK.

Ms Stephanie Hynes, Centre for Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine, King’s College London, London SE1 9RT, UK; Centre for Developmental Neurobiology/MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King’s College London, London SE1 1UL, UK.

Dr Andrew Lowe, Centre for Developmental Neurobiology, King’s College London, London SE1 1UL, UK.

Prof Juan Burrone, Centre for Developmental Neurobiology/MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King’s College London, London SE1 1UL, UK.

Prof Virgile Viasnoff, Mechanobiology Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117411.

Dr Ivo Lieberam, Centre for Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine, King’s College London, London SE1 9RT, UK; Centre for Developmental Neurobiology/MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King’s College London, London SE1 1UL, UK.

References

- [1].Ericson J, Rashbass P, Schedl A, Brenner-Morton S, Kawakami A, van Heyningen V, Jessell TM, Briscoe J. Cell. 1997;90:169–180. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lieberam I, Agalliu D, Nagasawa T, Ericson J, Jessell TM. Neuron. 2005;47:667–679. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Ebens A, Brose K, Leonardo ED, Hanson MG, Jr, Bladt F, Birchmeier C, Barres BA, Tessier-Lavigne M. Neuron. 1996;17:1157–1172. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kania A, Jessell TM. Neuron. 2003;38:581–596. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Gautam M, Noakes PG, Mudd J, Nichol M, Chu GC, Sanes JR, Merlie JP. Nature. 1995;377:232–236. doi: 10.1038/377232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Smith MA, Yao YM, Reist NE, Magill C, Wallace BG, McMahan UJ. The Journal of experimental biology. 1987;132:223–230. doi: 10.1242/jeb.132.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kim N, Stiegler AL, Cameron TO, Hallock PT, Gomez AM, Huang JH, Hubbard SR, Dustin ML, Burden SJ. Cell. 2008;135:334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yang X, Arber S, William C, Li L, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Birchmeier C, Burden SJ. Neuron. 2001;30:399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Misgeld T, Burgess RW, Lewis RM, Cunningham JM, Lichtman JW, Sanes JR. Neuron. 2002;36:635–648. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Missias AC, Mudd J, Cunningham JM, Steinbach JH, Merlie JP, Sanes JR. Development (Cambridge, England) 1997;124:5075–5086. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.24.5075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Brown RH, Jr, Robberecht W. Semin Neurol. 2001;21:131–139. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-15260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fischer LR, Culver DG, Tennant P, Davis AA, Wang M, Castellano-Sanchez A, Khan J, Polak MA, Glass JD. Exp Neurol. 2004;185:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cantor S, Zhang W, Delestree N, Remedio L, Mentis GZ, Burden SJ. eLife. 2018;7 doi: 10.7554/eLife.34375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yamanaka K, Chun SJ, Boillee S, Fujimori-Tonou N, Yamashita H, Gutmann DH, Takahashi R, Misawa H, Cleveland DW. Nature neuroscience. 2008;11:251–253. doi: 10.1038/nn2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Nagai M, Re DB, Nagata T, Chalazonitis A, Jessell TM, Wichterle H, Przedborski S. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:615–622. doi: 10.1038/nn1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Di Giorgio FP, Carrasco MA, Siao MC, Maniatis T, Eggan K. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:608–614. doi: 10.1038/nn1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tripathi P, Rodriguez-Muela N, Klim JR, de Boer AS, Agrawal S, Sandoe J, Lopes CS, Ogliari KS, Williams LA, Shear M, Rubin LL, et al. Stem cell reports. 2017;9:667–680. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wichterle H, Lieberam I, Porter JA, Jessell TM. Cell. 2002;110:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00835-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Mazzoni EO, Mahony S, Iacovino M, Morrison CA, Mountoufaris G, Closser M, Whyte WA, Young RA, Kyba M, Gifford DK, Wichterle H. Nat Methods. 2011;8:1056–1058. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jung H, Lacombe J, Mazzoni EO, Liem KF, Jr, Grinstein J, Mahony S, Mukhopadhyay D, Gifford DK, Young RA, Anderson KV, Wichterle H, et al. Neuron. 2011;67:781–796. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Alami NH, Smith RB, Carrasco MA, Williams LA, Winborn CS, Han SS, Kiskinis E, Winborn B, Freibaum BD, Kanagaraj A, Clare AJ, et al. Neuron. 2014;81:536–543. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Barmada SJ, Serio A, Arjun A, Bilican B, Daub A, Ando DM, Tsvetkov A, Pleiss M, Li X, Peisach D, Shaw C, et al. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:677–685. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sternfeldn MJ, Hinckley CA, Moore NJ, Pankratz MT, Hilde KL, Driscoll SP, Hayashi M, Amin ND, Bonanomi D, Gifford WD, Sharma K, et al. eLife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.21540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fischbach GD. Dev Biol. 1972;28:407–429. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(72)90023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Magloire V, Streit J. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1487–1497. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) Ionescu A, Zahavi EE, Gradus T, Ben-Yaakov K, Perlson E. Eur J Cell Biol. 2016;95:69–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zahavi EE, Ionescu A, Gluska S, Gradus T, Ben-Yaakov K, Perlson E. J Cell Sci. 2015;128:1241–1252. doi: 10.1242/jcs.167544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].a) Miles GB, Yohn DC, Wichterle H, Jessell TM, Rafuse VF, Brownstone RM. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7848–7858. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1972-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chipman PH, Zhang Y, Rafuse VF. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Steinbeck JA, Choi SJ, Mrejeru A, Ganat Y, Deisseroth K, Sulzer D, Mosharov EV, Studer L. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:204–209. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Bakooshli MA, Lippmann ES, Mulcahy B, Tung K, Pegoraro E, Ahn H, Ginsberg H, Zhen M, Ashton RS, Gilbert PM. bioRxiv. 2018 [Google Scholar]; b) Sakar MS, Neal D, Boudou T, Borochin MA, Li Y, Weiss R, Kamm RD, Chen CS, Asada HH. Lab on a chip. 2012;12:4976–4985. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40338b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].a) Uzel SGM, Platt RJ, Subramanian V, Pearl TM, Rowlands CJ, Chan V, Boyer LA, So PTC, Kamm RD. Science advances. 2016;2:e1501429. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Osaki T, Uzel SGM, Kamm RD. Science Advances. 2018;4:eaat5847. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1263–1268. doi: 10.1038/nn1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Machado CB, Kanning KC, Kreis P, Stevenson D, Crossley M, Nowak M, Iacovino M, Kyba M, Chambers D, Blanc E, Lieberam I. Development. 2014;141:784–794. doi: 10.1242/dev.097188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bryson JB, Machado CB, Crossley M, Stevenson D, Bros-Facer V, Burrone J, Greensmith L, Lieberam I. Science. 2014;344:94–97. doi: 10.1126/science.1248523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Henderson CE, Phillips HS, Pollock RA, Davies AM, Lemeulle C, Armanini M, Simmons L, Moffet B, Vandlen RA, Simpson LC, et al. Science. 1994;266:1062–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.7973664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lin JY, Knutsen PM, Muller A, Kleinfeld D, Tsien RY. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1499–1508. doi: 10.1038/nn.3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].a) Gao BX, Ziskind-Conhaim L. Journal of neurophysiology. 1998;80:3047–3061. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Takazawa T, Croft GF, Amoroso MW, Studer L, Wichterle H, Macdermott A. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Park JW, Vahidi B, Taylor AM, Rhee SW, Jeon NL. Nature protocols. 2006;1:2128–2136. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Millet LJ, Stewart ME, Sweedler JV, Nuzzo RG, Gillette MU. Lab on a chip. 2007;7:987–994. doi: 10.1039/b705266a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Masters T, Engl W, Weng ZL, Arasi B, Gauthier N, Viasnoff V. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Acevedo-Arozena A, Kalmar B, Essa S, Ricketts T, Joyce P, Kent R, Rowe C, Parker A, Gray A, Hafezparast M, Thorpe JR, et al. Disease models & mechanisms. 2011;4:686–700. doi: 10.1242/dmm.007237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Yang YM, Gupta SK, Kim KJ, Powers BE, Cerqueira A, Wainger BJ, Ngo HD, Rosowski KA, Schein PA, Ackeifi CA, Arvanites AC, et al. Cell stem cell. 2013;12:713–726. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bruijn LI, Becher MW, Lee MK, Anderson KL, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Sisodia SS, Rothstein JD, Borchelt DR, Price DL, Cleveland DW. Neuron. 1997;18:327–338. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Re DB, Le Verche V, Yu C, Amoroso MW, Politi KA, Phani S, Ikiz B, Hoffmann L, Koolen M, Nagata T, Papadimitriou D, et al. Neuron. 2014;81:1001–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].a) Demers CJ, Soundararajan P, Chennampally P, Cox GA, Briscoe J, Collins SD, Smith RL. Development (Cambridge, England) 2016;143:1884–1892. doi: 10.1242/dev.126847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shi P, Nedelec S, Wichterle H, Kam LC. Lab Chip. 2010;10:1005–1010. doi: 10.1039/b922143c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kaufman AM, Milnerwood AJ, Sepers MD, Coquinco A, She K, Wang L, Lee H, Craig AM, Cynader M, Raymond LA. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:3992–4003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4129-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Cooper ST, Maxwell AL, Kizana E, Ghoddusi M, Hardeman EC, Alexander IE, Allen DG, North KN. Cell motility and the cytoskeleton. 2004;58:200–211. doi: 10.1002/cm.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Juhas M, Bursac N. Biomaterials. 2014;35:9438–9446. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].a) Katz LC, Shatz CJ. Science (New York, N Y ) 1996;274:1133–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Andreae LC, Burrone J. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2014;27:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].a) Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. The Journal of physiology. 1970;206:419–436. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Burrone J, O'Byrne M, Murthy VN. Nature. 2002;420:414–418. doi: 10.1038/nature01242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zheng JQ, Felder M, Connor JA, Poo MM. Nature. 1994;368:140–144. doi: 10.1038/368140a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Park J-S, Hoke A. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, Caliendo J, Hentati A, Kwon YW, Deng HX, et al. Science. 1994;264:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Rao L, Qian Y, Khodabukus A, Ribar T, Bursac N. Nat Commun. 2018;9:126. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02636-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wefelmeyer W, Cattaert D, Burrone J. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:9757–9762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502902112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.