On October 4, 2001, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported the first case of an anthrax outbreak (1,2). At the beginning of the outbreak, ciprofloxacin was the only agent approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for postexposure prophylaxis against Bacillus anthracis infection. The CDC later revised its recommendations to include doxycycline (3), but by then ciprofloxacin had gained much public prominence (4–6). This was perhaps best exemplified by Tom Brokaw’s holding up a bottle of the drug on camera and closing his NBC Nightly News broadcast with the statement, “In Cipro we trust”(7). By early November, approximately 32,000 people had initiated prophylaxis with ciprofloxacin or doxycycline (8).

During the outbreak, media reports indicated that consumers were purchasing ciprofloxacin online (9). Web sites that require buyers to mail or fax written prescriptions from their physicians are generally considered valuable additions to the health care industry (10) and can voluntarily join the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy Verified Internet Pharmacy Practice Sites program to demonstrate their compliance with inspection criteria and state licensing requirements (11). Many other Web sites prescribe and dispense prescription medications on the basis of little more than a simple online questionnaire (10,12–14). The American Medical Association (AMA) has characterized such practices as “dangerous and highly inappropriate”(15). In the absence of effective regulation, however, these questionably legal entrepreneurial activities have continued. The potential public health consequences of unregulated online ciprofloxacin sales include drug shortages due to hoarding (16), antibiotic resistance (17), and adverse drug reactions (18).

Previous investigators characterized the poor consumer safeguards associated with the online sale of prescription medications, notably sildenafil, but did not analyze the rapidity with which they emerged in response to escalating demand (10,12–14). The acute setting of the anthrax outbreak provided us with a unique opportunity to study the dynamic structure of the Internet pharmacy market. We therefore sought to document the onset and longevity of Web sites selling ciprofloxacin, as well as to evaluate their content.

METHODS

Selection of Web Sites

We identified 11 search engines that either cover more than 10% of the Internet (19) or rank among the top five according to market research firms (20,21). For each search engine, we entered four terms: cipro, cipro AND buy, anthrax AND cipro, and anthrax AND antibiotics. From the first 100 results generated by each query, we identified all nonduplicative English-language sites that sold any generic or branded form of ciprofloxacin without requiring buyers to mail or fax written prescriptions from their physicians.

Data Collection

We identified Web sites from October 28, 2001, to October 31, 2001, and compiled the following information for each site: date of site creation, contact information, Verified Internet Pharmacy Practice Sites certification, other medications sold, information provided regarding ciprofloxacin or anthrax, requirements for purchase, and lowest price charged. The first two items were obtained from Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers–accredited registrar databases (22). Web sites were categorized into two groups: those with creation dates through October 4, 2001 (pre-outbreak) and those created after October 4 (post-outbreak). To determine Verified Internet Pharmacy Practice Sites certification, we checked the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy Web site (11). The remaining items were obtained from the Web sites themselves. Clinical claims and warnings were checked against the FDA-approved package insert and the Consensus Statement of the Working Group on Civilian Biodefense (23). Finally, we recorded the price of the lowest-priced package offered on the Web site and any additional fees. After the Web site was first identified, we checked each site daily for 2 weeks and noted if it discontinued selling ciprofloxacin only or ceased all operations.

Statistical Analysis

We used Stata software (version 7.0, Stata Corporation, College Station, Tex.) to estimate means and proportions. To examine the relation between date of creation and site characteristics, including content, price, and 14-day survival, we used chi-squared tests (for categorical variables), rank sum tests (for continuous variables), and the Wilcoxon test (for survival).

RESULTS

We identified 59 Web sites selling ciprofloxacin without prescription, 23 (39%) of which were established during the 2 weeks following October 4, 2001. None of the sites was certified by the Verified Internet Pharmacy Practice Sites program. Forty-eight sites (81%) were registered to U.S. addresses; the rest were registered to addresses in New Zealand (three sites), Mexico (two sites), Brazil, Ireland, Italy, Malaysia, and The Netherlands. Thirty sites (51%) sold other medications in addition to ciprofloxacin (usually sildenafil), and 22 sites (37%) provided a telephone number for customers with questions.

Seventeen sites (29%) displayed no information about potential adverse effects, and 16 sites (27%) did not mention contraindicated use in patients with a history of hypersensitivity to quinolone antibiotics. Eleven sites (19%) did not require the customer to fill out a medical questionnaire for purchase. On eight sites (14%), we documented false or misleading clinical claims and warnings. For example, one site stated, “Once exposed to Anthrax half of all deaths occur within 24 to 48 hours”(24).

While 50 sites (85%) specifically mentioned an indication for postexposure prophylaxis against inhalational anthrax, only 34 (68%) stated that a full dosing course is 60 days (25). Of these 34 sites, only four (12%) sold the “60-day” package. However, 20 sites (35%) sold a “3-day” package, and 21 sites (37%) sold a “7-day” package. The median lowest per-tablet price, including ancillary charges, was $6.95 (interquartile range, $5.67 to $11.36), a 50% markup over the U.S. wholesale price of $4.67 (26).

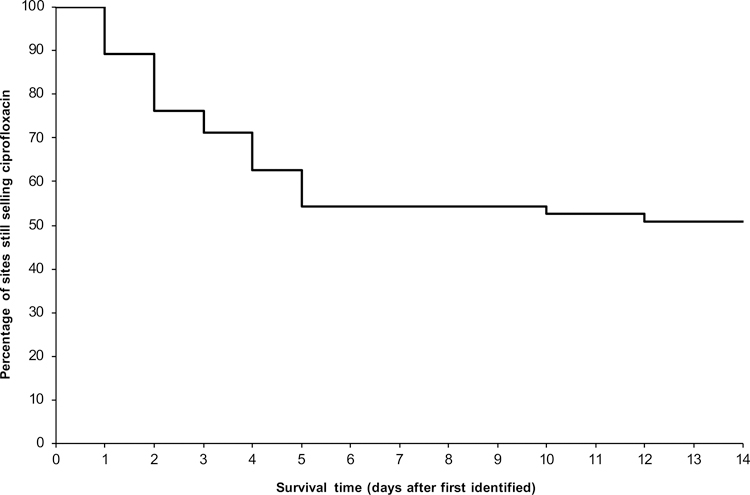

During the follow-up, 29 sites (49%) discontinued ciprofloxacin sales, of which 17 continued other operations and 12 ceased operations entirely.

Compared with their pre-outbreak counterparts, post-outbreak sites were more likely to sell ciprofloxacin exclusively (96% [22/23] vs. 19% [7/36], P < 0.001) and to mention an indication for postexposure prophylaxis (100% [23/23] vs. 75% [24/36], P = 0.009). The two groups were otherwise statistically similar in the content variables, price, and survival.

DISCUSSION

At least 59 Web sites selling ciprofloxacin without prescription—23 of which were created within 2 weeks after an anthrax outbreak was reported—were readily accessible to Internet users searching for information on ciprofloxacin or anthrax. These possibly illegal sites were characterized by poor quality of information, inadequate consumer safeguards, and high prices. Post-outbreak sites generally sold only ciprofloxacin and mentioned an indication for postexposure prophylaxis, suggesting that they were created in response to public fears. The presence of false or misleading claims underscores our concerns about potential exploitative behavior.

During the 2-week follow-up, about half of all sites ceased ciprofloxacin sales, raising questions about the continuity of service provided to customers as well as highlighting the need for regulatory authorities to respond quickly. State authorities brought enforcement actions against persons associated with three Web sites in our sample, of which two were still operating at the end of our study (27–29). These enforcement actions may have had spillover effects on nontargeted sites, contributing to the rapid decline in sales we observed. Alternatively, the sites may have voluntarily withdrawn because of perceived lack of further income-generating potential, illustrating the lability of Web-based companies.

Several study limitations should be considered. First, we may have missed sites that had already ceased ciprofloxacin sales by October 28, 2001. Second, while we were able to determine the date of Web site creation, we were unable to determine retrospectively when a particular site began selling ciprofloxacin. Pre-outbreak sites likely were originally created to sell other medications, e.g., sildenafil (10,12–14), but began selling ciprofloxacin as media coverage intensified.

Voluntary and self-monitoring approaches have not addressed the issue adequately. None of the sites in our sample opted for certification under the Verified Internet Pharmacy Practice Sites program, suggesting the limits of the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy’s voluntary approach. Prescribing and dispensing medications solely on the basis of an online medical questionnaire violates AMA ethical and professional guidelines (30); furthermore, the AMA’s strong pronouncements appear to have done little to deter such practices.

The FDA recently stated that it would not issue long-awaited guidelines on whether the promotion of FDA-regulated products on the Internet would constitute labeling (31). In response to the Internet outbreak, the FDA ordered all private ciprofloxacin shipments arriving from overseas to be stopped at the border (32). The FDA also sent 11 “cyber” letters to overseas Web sites selling foreign unapproved versions of ciprofloxacin (33). Of the 59 Web sites in our sample, only three were sent such letters, two of which were still in operation at the end of the study. The FDA acknowledges that states have traditionally regulated the prescribing and dispensing of drugs (34), but the states have not filled the regulatory vacuum. Primary regulation occurs via states’ enforcement of state medical and pharmacy practice acts and consumer protection laws (27–29,35–37), yet most states have not adopted laws specific to Internet prescribing or dispensing (38,39). Furthermore, state enforcement efforts are often hampered by Web site sales across state lines (35).

We emphasize the need for stronger FDA guidelines and enforcement to regulate the sale of prescription medications on the Internet. Our report makes clear that Web site operators selling prescription medications can act rapidly to capitalize on emerging opportunities and recede, evading apprehension, with equal swiftness. Regulatory authorities must have the resources and adequate legal authority to act with similar urgency.

Figure 1.

Creation dates for Web sites observed to be selling ciprofloxacin from October 28, 2001, to October 31, 2001 (n = 59 sites). Black shading represents sites selling ciprofloxacin exclusively (n = 29); gray shading represents sites selling medications in addition to ciprofloxacin (n = 30). Inset shows creation dates for October 2001.

Figure 2.

Survival of Web sites selling ciprofloxacin (n = 59 sites). Within 2 weeks, the number of sites selling ciprofloxacin had decreased by about half.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We appreciate the input of students and lecturers in the course “Activism and Medicine” (http://home.cwru.edu/activism) at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio. Mr. Tsai is a National Research Service Award Trainee supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Institutional Training Award (T32) HS-00059–06.

Mr. Tsai is a National Research Service Award Trainee supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Institutional Training Award (T32) HS-00059–06.

REFERENCE

- 1.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notice to readers: ongoing investigation of anthrax—Florida, October 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50:877. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: investigation of bioterrorism-related anthrax and interim guidelines for clinical evaluation of persons with possible anthrax. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50:941–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: investigation of bioterrorism-related anthrax and interim guidelines for exposure management and antimicrobial therapy, October 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50:909–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hensley S Purchases of antibiotic jump on fears of bioterrorism, but doctors see risks. Wall Street Journal October 9, 2001:A1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen M, Pear R. Anthrax fears send demand for a drug far beyond output. New York Times October 16, 2001:A1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oransky I Antibiotic overuse can silence medicine’s big guns. USA Today November 15, 2001:A15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurtz H Tom Brokaw, putting a familiar face on the anthrax story. Washington Post October 18, 2001:C1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: investigation of bioterrorism-related anthrax and adverse events from antimicrobial prophylaxis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50:973–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Va LeDuc D.., Md. warn of Cipro sales on Internet. Washington Post October 27, 2001:B4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catizone C Drugstores on the Net: The Benefits and Risks of On-Line Pharmacies. Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Commerce, 106th Cong, 1st Sess (1999). Serial no. 106–51. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. Verified Internet Pharmacy Practice Sites Database Available at: http://www.nabp.net/vipps/intro.asp. Accessed October 30, 2001.

- 12.Armstrong K, Schwartz JS, Asch DA. Direct sale of sildenafil (Viagra) to consumers over the Internet. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1389–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloom BS, Iannacone RC. Internet availability of prescription pharmaceuticals to the public. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:830–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Internet Pharmacies: Adding Disclosure Requirements Would Aid State and Federal Oversight. U.S. General Accounting Office; October 2000. GAO-01–69. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abromowitz HI. Drugstores on the Net: The Benefits and Risks of On-Line Pharmacies. Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Commerce, 106th Cong, 1st Sess (1999). Serial no. 106–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez B, Harris G. Doctors struggle to allay patients’ fears as requests for anthrax antibiotic surge. Wall Street Journal October 15, 2001:B1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hart CA, Beeching NJ. Prophylactic treatment of anthrax with antibiotics. BMJ 2001;323:1017–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: adverse events associated with anthrax prophylaxis among postal employees—New Jersey, New York City, and the District of Columbia Metropolitan Area, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50:1051–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence S, Giles CL. Accessibility of information on the web. Nature 1999;400:107–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan D Jupiter Media Metrix search engine ratings Available at: http://www.searchenginewatch.com/reports/mediametrix.html. Accessed October 30, 2001.

- 21.Sullivan D Nielsen//NetRatings search engine ratings Available at: http://www.searchenginewatch.com/reports/netratings.html. Accessed October 30, 2001.

- 22.Descriptions and contact information for ICANN-accredited registrars Available at: http://www.icann.org/registrars/accreditation-qualified-list.html. Accessed October 30, 2001.

- 23.Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, et al. Anthrax as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. Working Group on Civilian Biodefense. JAMA 1999;281:1735–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cipro-anthrax-cure.com [Web site]. Available at: http://www.cipro-anthrax-cure.com. Accessed November 2, 2001.

- 25.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: investigation of anthrax associated with intentional exposure and interim public health guidelines, October 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50:889–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pesta J, Pearl D. Indian drug makers emerging as a potential source of Cipro. Wall Street Journal October 19, 2001:A13. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Angwin J Medical board in North Carolina acts to curb online prescriptions for Cipro. Wall Street Journal October 29, 2001:B8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shamp J Cipro allegedly prescribed over Net. Herald-Sun [Durham, North Carolina] November 3, 2001:C1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kazak DR. County sues to stop three Cipro sellers on Internet. Chicago Daily Herald November 3, 2001:3. [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Medical Association. Report of the Board of Trustees: internet prescribing. Board of Trustees Report 35-A-99, 1999 Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/meetings/public/annual99/reports/onsite/bot/rtf/bot35.rtf. Accessed June 5, 2002.

- 31.Web site labeling claims guidance would be “quickly outdated”—FDA. F-D-C Reports [“The Tan Sheet”] November 26, 2001:18. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carey B, Cimons M. FDA to halt Cipro imports in bid to stop illegal sales over Internet. Los Angeles Times October 20, 2001:A1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Issues Cyber-Letters to Web Sites Selling Unapproved Foreign Ciprofloxacin November 1, 2001. FDA Talk Paper T01–54. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodcock J Drugstores on the Net: The Benefits and Risks of On-Line Pharmacies. Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Commerce, 106th Cong, 1st Sess (1999). Serial no. 106–51. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stovall CJ. Enforcing the Laws on Internet Pharmaceutical Sales: Where Are the Feds? Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Commerce, 106th Cong, 2nd Sess (2000). Serial no. 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewin T Anthrax drug sold online leads to suit. New York Times January 12, 2002:A9. [Google Scholar]

- 37.White RD. State seeks to fine online pharmacy. Los Angeles Times May 29, 2002:A1. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silverman RD. Regulating medical practices in the cyber age: issues and challenges for state medical boards. Am J Law Med 2000;26:255–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chin T Rx surveillance: watch out for prescribing over the Internet. Am Med News 2001;44:23–24. [Google Scholar]