Abstract

Neuronal microtubule (MT) tau protein provides cytoskeleton to neuronal cells and plays a vital role including maintenance of cell shape, intracellular transport, and cell division. Tau hyperphosphorylation mediates MT destabilization resulting in axonopathy and neurotransmitter deficit, and ultimately causing Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a dementing disorder affecting vast geriatric populations worldwide, characterized by the existence of extracellular amyloid plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles in a hyperphosphorylated state. Pre-clinically, streptozotocin stereotaxically mimics the behavioral and biochemical alterations similar to AD associated with tau pathology resulting in MT assembly defects, which proceed neuropathological cascades. Accessible interventions like cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA antagonist clinically provides only symptomatic relief. Involvement of microtubule stabilizers (MTS) prevents tauopathy particularly by targeting MT oriented cytoskeleton and promotes polymerization of tubulin protein. Multiple in vitro and in vivo research studies have shown that MTS can hold substantial potential for the treatment of AD-related tauopathy dementias through restoration of tau function and axonal transport. Moreover, anti-cancer taxane derivatives and epothiolones may have potential to ameliorate MT destabilization and prevent the neuronal structural and functional alterations associated with tauopathies. Therefore, this current review strictly focuses on exploration of various clinical and pre-clinical features available for AD to understand the neuropathological mechanisms as well as introduce pharmacological interventions associated with MT stabilization. MTS from diverse natural sources continue to be of value in the treatment of cancer, suggesting that these agents have potential to be of interest in the treatment of AD-related tauopathy dementia in the future.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, epothiolones, microtubule destabilization, microtubule stabilizers, tauopathy, taxanes

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is acknowledged as a progressive neurodegenerative disorder causing significant disruption of normal brain structure and function including degeneration beginning in the medial temporal lobe. Specifically, the disease starts in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus and the major fiber tracts that connect it to the cerebral cortex (fornix and cingulum), amygdala, cingulate gyrus, and thalamus, manifested by cognitive and memory deterioration and characterized by accumulation of extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), destruction of cholinergic neurons in cerebral cortex and hippocampus, microgliosis and astrocytosis, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and excitotoxicity [1–3]. AD has been classified into two groups, depending on its onset: the first classification is familial AD, related to genetic alterations of amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin1 (PSEN1), and presenilin 2 (PSEN2). This group represents approximately about 3% of the diseased patients. The other classification group is late-onset AD (LOAD), also known as sporadic, which is due to polymorphisms of apolipoprotein E (APOE) ɛ4, accounts for the remaining 97% of the cases [4, 5]. The sign and symptoms are categorized into mild, moderate, and severe, including memory loss, language problems, mood swings, behavioral changes, unable to learn new info, agitation, aggression, ataxia (loss of muscle control and balance), aphasia (impairment of language), amnesia (forgetfulness), loss of visuospatial function (ability to recognize faces and objects), praxis (ability to perform purposeful movements), confusion, and motor disturbances [6, 7]. Prevalence of AD in India is >4 million people and worldwide around 46.8 million people [8]. Currently, the cause of AD remains poorly understood and no medications are available to stop or reverse its progression [9]. Currently available treatments like acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (rivastigmine, galantamine, donepezil) and N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist (memantine) show least impact on the disease and contribute symptomatic relief only but unsuccessful to provide definite cure [10, 11]. To render this disease, new therapeutic targets are available to tackle AD directly. MT destabilization is accompanied by tau hyperphosphorylation. Tau proteins that are abundant in nerve cells perform the function of stabilizing MT [12]. Compounds targeting MT have been massively successful clinically as chemotherapeutic agents [13]. MT targeting agents have been shown to have the potential to treat neurodegenerative disease.

ETIOPATHOLOGICAL FACTORS

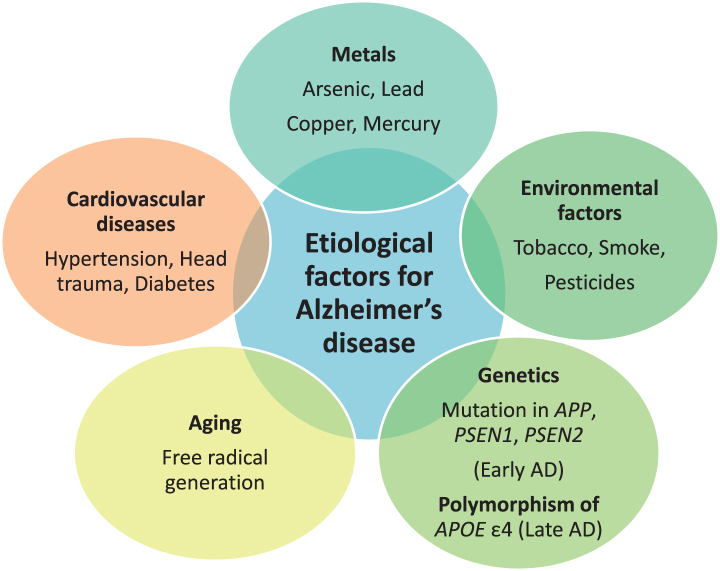

The etiology behind AD is multifactorial. Exposure to neurotoxic metals like arsenic, lead, copper, mercury, and aluminum have been involved in AD due to their tendency to increase phosphorylation of tau protein and increase Aβ peptide. Other putative etiological factors involve environmental pollutants, genetic factors, disease state, and aging. Environmental pollutants including tobacco, smoke, and pesticides, like deltamethrin and carbofuran, are responsible for disrupting tau function [14]. Head trauma, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus are disease conditions that can lead to AD [15, 16]. Genetics play a major role in causing AD. Mutations in APP located on chromosome 21 q, PSEN1 on chromosome 14 q, and PSEN2on chromosome 1qare associated with early-onset AD, or familial AD, and development of the disease before the age of 65 year. Polymorphism of APOE with the ɛ4 allele is responsible for causing late-onset AD [17]. APOE is located on chromosome 19 q. ApoE is associated with cholesterol transport in the brain. Common alleles of APOE are ɛ2, ɛ3, and ɛ4. APOE ɛ4 is responsible for LOAD risk, whereas APOE ɛ2 shows a protective role. The predominant risk factor for sporadic AD is aging. Aging also impacts AD through two mechanisms as free radicals generated during cellular respiration in aging lead to AD and another mechanism is mutation in messenger RNA of amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP) and ubiquitin B [18]. The majority of AD cases typically have an onset after 65 years of age [19]. The various etiological factors are mentioned in Fig. 1.

Fig.1.

Etiological factors responsible for Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

NEUROPATHOLOGY OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE ASSOCIATED WITH TAU DYSFUNCTION

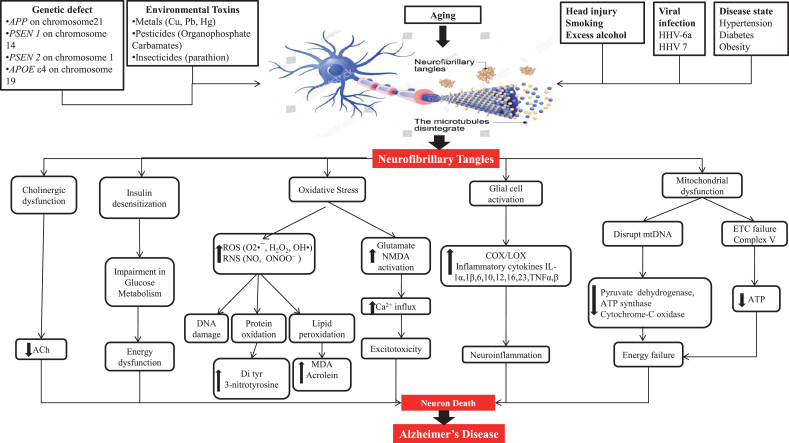

Pathogenesis gives information about the cause of AD as well as therapeutic targets. Some plausible etiological factors like genetic defects of APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, and APOEɛ4; environmental toxins like metals, pesticides, and insecticides; head injury; smoking; excess alcohol; viral infection through viruses like HHV-6a and HHV 7; and diseases like hypertension, diabetes, and obesity are somewhat responsible for AD hallmarks including amyloid plaques and NFT [5, 14–16]. NFT are formed due to hyperphosphorylation of tau protein and its further processing. Figure 2 shows a representation of the mechanism of tau pathology and the way it additionally causes pathological alterations inside cells like cholinergic dysfunction, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and glial cell activation.

Fig.2.

Neuropathological factors engaged to cause Alzheimer’s disease.

Tau pathogenesis

Tau protein is most profusely expressed in axons of central nervous system (CNS) neurons but can also be found in the somatodendritic part of neurons, oligodendrocytes, and non-neural tissues [20, 21]. The most important role of tau protein is to promote assembly and stability of MT [20, 22]. In AD, hyperphosphorylation of certain amino acids in tau proteins causes the proteins to detach from the MT, disturbing the cytoskeleton of neurons and transport system, resulting in starvation of neurons and, ultimately, cell death. Hyperphosphorylated tau thus plays a crucial role in intracellular neurofibrillary alterations and the pathogenesis of AD and related tauopathies [23, 24]. Before the tangle formation, tau undergoes a series of post-translational modifications, including hyperphosphorylation, acetylation, N-glycosylation and truncation, which is different from the normal tau that is seen in healthy brains [25, 26]. Post-translational modifications of tau interfere with tau–MT binding and promote tau misfolding [26].

Steps lagging behind post-translational modifications of tau

Hyperphosphorylation of tau protein

With the identification of tau as the primary component of AD-associated NFTs, the aggregated tau was believed to be hyperphosphorylated. Abnormal phosphorylation of the tau protein affects its ability to bind tubulin and promote MT assembly [26, 27]. In AD, the pattern of phosphorylation changes as the disease progresses. Phosphorylation at sites such as Ser199, Ser202/205, Thr231, and Ser262 seems to be linked with pre-tangles in the neuronal processes [28]. Tau level in somatodendritic compartment increases. The reason behind the hyperphosphorylation of tau protein is an imbalance of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of tau. This imbalance is associated by a reduced tau protein dephosphorylation or by an overactivity of the phosphorylating protein kinases. The degree of phosphorylation reflects abnormal activity of both protein kinases and phosphatases. Levels of active cyclin-dependent-like kinase 5 (CDK5), glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), and its regulator c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) are associated with neurofibrillary pathology and are upregulated in AD [29]. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is one of only a few tau phosphatases and is responsible for the total tau phosphatase activity. The total phosphatase activity and the activities of PP2A and PP5 toward tau were significantly decreased, whereas that of PP2B was increased in AD brain [30]. Expression of PP2A and its activators is significantly reduced in the brains of individual suffering from AD compared with age-matched controls, whereas PP2A inhibitors are upregulated. Interestingly, PP2A also regulates GSK-3β, CDK5, and JNK, providing a surplus route to influence tau phosphorylation [31].

Acetylation of tau protein

In addition to being hyperphosphorylated, tau from patients with AD and other tauopathies is more acetylated than that within the brains of cognitively healthy individuals. Lysine acetylation contends phosphorylation in regulating diverse cellular functions, including energy metabolism, signaling from the plasma membrane, and cytoskeleton dynamics. Enzymes that transfer an acetyl group to the protein are called histone acetyltransferase or lysine acetyltransferase. Enzymes that eliminate an acetyl group from the protein are called histone deacetylases or lysine deacetylases [32]. Like phosphorylation, tau acetylation can arise through multiple mechanisms, including histone acetyltransferase p300, cAMP-responsive element-binding protein, or auto-acetylation, with sirtuin 1 and histone deacetylases 6 acting to deacetylate tau [33]. Improper functioning of this process produces dysfunction in multiple systems, thereby leading to neurodegeneration. Tau pathology is due to contribution of acetylation which leads to tau cleavage, preventing ubiquitin binding and inhibiting tau turnover.

Carboxy-terminal truncation of tau protein

Caspase activation is detected in the AD brain, and active caspases are found within tangle-bearing neurons. Furthermore, tau is cleaved by caspase-3. Besides caspase-3, other caspases are capable of cleaving tau at Asp421 [34]. During the characterization of paired helical filaments isolated from the brains of individuals with AD, it was discovered that tau had undergone carboxy-terminal truncation by caspase 3 [26]. Using a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against the caspase-cleaved carboxyl-terminus of tau after cleavage at Asp421, analysis of temporal cortex brain lysates revealed that caspase-cleaved tau was found in mild cognitive impairment and AD but not in controls. In the case of AD, Aβ promotes caspase activation. In addition to tau cleavage at Asp421, other caspase cleavage products of tau have been identified in the AD brain. Caspase-6 cleaved tau has been identified in intracellular tangles, extracellular tangles, pretangles, neuropil threads, and neuritic plaques. In additional to C-terminal caspase cleavage of tau, tau can be cleaved at the N-terminus by caspase-6 [34].

O-GlcNAcylation and N-glycosylation of tau protein

O-GlcNAcylation, a type of O-glycosylation, seems to be protective against tauopathies. O-GlcNAcylation is a process regulated by glucose metabolism markedly decrease in AD. Impaired brain glucose metabolism leads to decrease in O-GlcNAcylation which further leads to abnormal phosphorylation of tau and neurofibrillary degeneration via downregulation of tau O-GlcNAcylation in AD. Decreased O-GlcNAcylation induces hyperphosphorylation of tau [35]. N-glycosylation of tau, which is thought to increase phosphorylation and pathological conformational changes, is increased in AD [26].

Neuropathological cascade associated with tau dysfunction

Oxidative stress and tau hyperphosphorylation

Oxidative stress takes place when reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) production are not adequately counterbalanced by an endogenous antioxidant defense system [36]. Accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau causes oxidative stress, but ROS have also been shown to stimulate tau hyperphosphorylation [37]. Accumulation of a truncated tau fragment has been described in sporadic AD cases, and cultured cortical neurons from a transgenic rat model expressing this truncated protein showed high levels of oxidative stress markers and an increased susceptibility to ROS [38]. Oxidative stress due to free radicals generate which attack phospholipid polyunsaturated fatty acids in cellular membrane can lead to lipid peroxidation, thereby results in formation of major end products 4-hydroxyl-2-nonenal (HNE), acrolein, and malondialdehyde, causing neurotoxicity to neurons [39]. HNE reacts with proteins forming stable covalent adducts to lysine, cysteine, and histidine residues, thereby producing carbonyl functionalities to the proteins, leading to oxidative damage called protein oxidation, and these protein carbonyls are mostly abundant in frontal, temporal, occipital, hippocampus, and inferior parietal lobe [40, 41]. RNS-like peroxynitrite causes tyrosine nitration of protein (3-nitrotyrosine and di tyrosine). Expanded dimensions of these proteins can be found in hippocampus and cortical areas. Increased levels of protein 3-nitrotyrosine and protein carbonyl result in alteration of antioxidant enzymes like glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, and catalase [42].

Glutamate excitotoxicity and tau hyperphosphorylation

Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter abundantly present in cortical and hippocampal regions involved in CNS functions like learning and memory and has low micromolar concentrations during normal conditions, but during synaptic transmission, its concentration increases from μM to mM because of its tendency having synaptic plasticity i.e., long-term potentiation (LTP) [43]. Glutamate receptors are ionotropic and metabotropic. Ionotropic receptors are transmembrane molecules that open or close a channel that allow small particles to travel in and out of cell. The ions that can travel through these receptors are K+, Na+, Cl–, and Ca2 +. Metabotopic receptors do not have channel that open or close [44]. Rather, they are connected to small chemical called G-protein. Once activated G-proteins go on and activate another molecule called secondary messenger. Ionotropic receptors are divided into α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), NMDA, and kainite [28]. NMDA receptors (NMDARs) are mainly essential for LTP induction. The resting potential of healthy neuron is normally around –70 mV, and at this potential, the Ca2 + channel of NMDAR is blocked by Mg2 + ions. Induction of LTP causes strong and prolonged release of glutamate in the synaptic cleft, and glutamate uptake is severely impaired due to pathological changes induced by ROS and lipid peroxidation end product HNE in excitatory amino acid transporter 2 (EAAT2), which is concentrated in perisynaptic astrocytes cell membrane and plays a role in the removal of excess glutamate from extracellular fluid, thereby limiting NMDAR activation. This glutamate excess will lead to overactivation of NMDARs [43, 45]. During LTP induction, glutamate binds to AMPA receptors leading to Na+ influx through AMPA receptors causing depolarization of the postsynaptic compartment and leading to activation of NMDARs to permit Ca2 + influx. In AD, there is overactivation of NMDARs which further leads to more influx of Ca2 + ions, and there is Ca2 + overload, which ultimately causes excitotoxicity [46]. Increased levels of mGluR2 are found in the hippocampus of individuals suffering from AD, and this correlates with elevated phosphorylated tau levels [47, 48]. Increased mGluR2 expression may result in increased intracellular Ca2 +, which may activate tau kinases [49]. Fyn kinase can regulate glutamatergic NMDAR activation by triggering phosphorylation and subsequent interaction of the N-methyl D-aspartate receptor subtype 2B (NR2B) subunit of the receptor with postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95). The NR2B/PSD-95/Fyn complex that is formed when NMDARs are activated increase Ca2 + influx, which can activate two key tau kinases, GSK-3β and CDK5 [50, 51]. It is therefore possible that NMDAR activation stabilizes the NR2B/PSD-95/Fyn complex, resulting in a constant activation of the NMDAR channel and increasing tau phosphorylation either by direct phosphorylation of tau via Fyn kinase or by activating other tau kinases, such as GSK-3β or CDK5 [52].

Insulin desensitization and tau hyperphosphorylation

Insulin plays multiple roles in the periphery, most especially in the regulation of tissue metabolism by controlling cellular glucose uptake. In contrast, the brain was previously considered insulin insensitive. However, it is now known that insulin does play several roles within the CNS at the cellular levels, including the regulation of neuronal survival and cognition [53]. Insulin is primarily derived from the periphery, and it can be shown that changes in peripheral insulin levels lead to alterations in CNS insulin signaling and could contribute to cognitive decline and pathogenesis. Impairment of CNS insulin signaling is due to decrease in brain insulin levels, e.g., due to decreased peripheral production or altered capacity for insulin to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), or a change in CNS insulin receptor (IR) sensitivity (e.g., IR desensitization due to elevated insulin levels). IRs is differentially expressed in various parts of brain like hippocampus, hypothalamus, cerebral cortex, and amygdala [54]. Under normal physiological conditions when insulin binds to the IR, a cascade regulates key downstream serine/threonine kinases such as, protein kinases B (AKT/PKB), mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), and extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) that eventually phosphorylate serine/threonine residues of insulin receptor substrate (IRS), and inhibiting insulin signaling in a negative feedback regulation. In neurons, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), AKT, GSK-3β, BCL-2 agonist of cell death (BAD), mTOR, and the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways are essential for cell survival signaling and are undertaken by the activity of the IR [55]. Therefore, alteration of the physiological activity of these pathways might be the source of alteration in normal neuronal performance, showing that brain insulin resistance could promote LOAD, precisely by inhibition of these pathways. The decrease in gene expression and protein levels of insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptors, and other downstream molecules leads to impaired acetylcholine production and cognitive performance in LOAD brain [56]. IR activation, through phosphorylated IRS proteins, results in activation of signaling pathways including PI3K and ERK [57]. Activation of PI3K⟶Akt cascade increase neuronal growth and survival [58]. Akt inactivates GSK-3β, which further inhibits tau phosphorylation [59]. There are number of studies that show insulin-regulated tau phosphorylation and increased rate of NFT formation [60, 61]. Insulin andIGF-1 regulate tau phosphorylation through the inhibition of GSK-3βvia the PI3K-protein kinase B (PI3K-PKB) signaling pathway [62]. Insulin and IGF-1 signaling normally prevents tau hyperphosphorylation in the brain [63]. In type 2 diabetes, increased GSK-3β activity might lead to an elevation of and increased tau phosphorylation [64]. IRS-1deficiency leads to insulin resistance in diabetes. Significantly, there is reduction in levels of IRS-1 and IRS-2occurring in AD brain, accompanied by elevated cytosolic phospho-IRS-1 (Ser 312 and 316) [65, 66]. Phosphorylation of IRS-1 (Ser 312 and 316) inhibits the regulation of insulin on GSK-3β activity, leading to further increase in hyperphosphorylation of tau [67]. Insulin resistance in the hippocampus might induce a neuroplasticity deficit, including deficits in spatial learning and memory.

Glial cell overactivation and tau hyperphosphorylation

Tau pathology is likely to induce microglial/astrocytic activation that is present near neurons and prone to directly favor the progression of neuroinflammation [68]. Microglial cells are the intrinsic macrophages of the CNS and thereby are responsible for monitoring and responding to injury and insult in the surrounding brain and serve as the brain’s natural defense mechanism [69]. Activated microglia express different types of cell surface molecules, including Fc receptors, scavenger receptors, cytokine and chemokine receptors, and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and have a wide variety of pattern recognition receptors from the Toll-like receptor group (TLR) that detect microbial intruders [70]. After stimulation, TLRs initiate a signal cascade that involves myeloid differentiation primary response 88 and the stimulation of transcription factors including nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and Activator protein-1. Following activation, microglia is able to trigger a pro-inflammatory cascade resulting in the release of cytotoxic molecules such as cytokines, complement factors [71]. Microglia release cytokines [(interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-16, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)]; chemokines [CC (CCL2/MCP-1, CCL3/MIP-1 β, CL4/MIP-1, CCL5/RANTES); CXC (CXCL8/IL8, CXCL9/MIG, CXCL10/IP-10, CXCL12/SDF-1α); CX3 C (CX3CL1/fractalkine)]; matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9); and eicosanoid (Prostaglandin D2, leukotriene C4, cathepsins B and L, and complement factors C1, C3, and C4), which also induce astrocyte chemotaxis around NFT. Microglial activation brings out the proliferation of astrocytes. Astrocytes require activation, which involves Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) that induces expression of class I or II MHC molecules; the microglia present antigens to CD8+ cells while the astrocytes present them to CD4+ cells. Microglia is more effective as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) when they are previously stimulated with IFN-γ. However, astrocytes are considered non-professional APCs [72]. Overactivation of microglia cells result in neuroinflammation.

Mitochondrial dysfunction and tau hyperphosphorylation

MT dysfunction can be due to hyperphosphorylated tau, which plays a pathological role, in addition to impairing axonal transport of organelles including mitochondria and results in synaptic dysfunction [73]. Tau, a major MT-associated protein, plays a consequential role in neuronal processes. Between the MT-binding domain and projection domain lays a basic proline-rich region, which contains ample phosphorylation sites. The interaction of the proline-rich region of tau with the MT-surface leads to MT stabilization [74]. Phosphorylation as the most chief post-translational modification of tau plays a crucial role in the dynamic equilibrium of tau with the MT. It has been found that the serine/threonine-directed phosphorylation of tau directly regulates the binding affinity of tau for MT [75]. The MT plays an essential role in axonal transport. Dysfunction of MT leads to abnormal axonal transport and synaptic dysfunction. By binding the MT, tau has profound effects on axonal transport, which allows signaling molecules, trophic factors, and essential organelles including mitochondria and so on, to travel along the axons [76]. To meet high energy demands and regulate calcium buffering of neuronal cells, efficient delivery of mitochondria in neurons is essential. The delivery of mitochondria is the task of MT with the help of proteins like kinenins and dynenins. Mitochondria are commodities that are delivered by MT-associated proteins, including tau, across axons into synapses. Balanced mitochondrial fission/fusion dynamics are important to meet high energy demands and enhance neuroprotective effects [77]. A group of guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) has been found to govern mitochondrial fission and fusion processes. Dynamin- like protein 1 (DLP-1 or Drp1) and a small molecule fission protein-1(Fis1) participate in the regulation of the fission process. The fusion process is regulated by mitofusin 1, mitofusin 2, and optic atrophy protein 1. Abnormal interaction between hyperphosphorylated tau and Drp1 causes an excessive mitochondrial fission process and further leads to the degeneration of mitochondria and synapses in brain [78]. Mitochondrial dynamics within the neuronal environment are regulated by the above-listed proteins. Over expression and hyperphosphorylation of tau impair distribution of mitochondria which further cause defects in axonal function and loss in synapses. It was filamentous, rather than soluble, forms of hyperphosphorylated tau that inhibited anterograde fast axonal transport by activating GSK-3 and axonal protein phosphatase. Defects in mitochondrial function are manifested by a variety of indicators, including decreased ATP synthesis, increased ROS production, impaired oxidative phosphorylation system complexes and antioxidant enzymes [73]. An inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation depolarizes mitochondria, which further impairs the ability of cells to buffer calcium loads. Elevated calcium interferes with mitochondrial action, which reduces ATP production. Neurons require a constant supply of energy for its normal functioning. Neurons have a restricted glycolytic capacity and they therefore depend on mitochondrial aerobic oxidative phosphorylation for energy needs [79]. Interestingly, oxidative phosphorylation is an important source of endogenous toxic free radicals, inclusive of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl (OH–), and superoxide (O2–) radicals that are byproducts of normal cellular respiration. These ROS generated are constantly neutralized by several efficient enzymatic processes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase, superoxide reductase, and catalase (CAT). If there is an excess of ROS generation, which overcomes the antioxidant capacity to neutralize them, it can lead to oxidative stress followed by mitochondrial dysfunction. ROS are produced by mitochondria target mitochondrial components such as lipids, proteins, and DNA causing lipid and protein peroxidation of cell membrane [80, 81].

Cholinergic dysfunction and tau hyperphosphorylation

Acetylcholine is a major neurotransmitter in the brain, having activity throughout the cortex, basal ganglia, and basal forebrain [82]. Acetylcholine is released from neurons projecting to a wide range of cortical and subcortical sites. These projections can be divided into two groups: the basal forebrain cholinergic system and the brainstem cholinergic system. The basal forebrain cholinergic system consists of cells located in the medial septal nucleus, the vertical and horizontal limbs of the diagonal band of Broca, and the nucleus basalis magnocellularis or nucleus basalis of Meynert (NBM) [83]. These structures send both cholinergic and non-cholinergic projections to a wide range of sites in the neocortex as well as limbic cortices such as cingulate cortex, entorhinal cortex, and hippocampus and other structures including the basolateral amygdala and the olfactory bulb. The brainstem cholinergic system includes neurons situated in the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus and laterodorsal pontine tegmentum principally innervating the thalamus and basal ganglia but also innervating the basal forebrain and serving as a minor component of the cholinergic innervation of cortical structures [84]. Cholinergic neuron density in the thalamus, striatum, limbic system, and neocortex is high, which suggests that cholinergic transmission is likely to be important for memory, learning, attention, and other higher brain functions. Neurofibrillary degeneration in the basal forebrain is believed to be the primary cause for the dysfunction and death of forebrain cholinergic neurons, giving rise to a widespread pre-synaptic cholinergic dysfunction [85]. NBM is in the basal forebrain which is the source of cortical cholinergic innervations and undergoes severe neurodegeneration in AD. Nicotinic ionotropic receptors and muscarinic metabotropic receptors of the cerebral cortex also undergo changes [86]. Most studies show a loss of nicotinic receptors in the cerebral cortex. There is a decrease of postsynaptic nicotinic receptors on cortical neurons. With respect to muscarinic receptors of the cerebral cortex, it is interesting that the muscarinic M1 receptors (mostly postsynaptic) are not decreased, whereas the M2 receptors (mostly presynaptic) are decreased. However, there is evidence that the remaining postsynaptic M1 receptors of the cerebral cortex may be dysfunctional. Loss of cortical cholinergic innervations is probably provoked by NFTs in the NBM. Cholinergic depletion then contributes to the cognitive impairment which ultimately leads to neuron death [82].

EXPERIMENTAL ANIMAL MODELS (TOXIN-INDUCED) FOR DECIPHERING THE PATHOGENESIS OF ALZHEIMER-TYPE DEMENTIAS

Animal models are used to study the development and progression of diseases and to test novel treatments before they reach clinically. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the use of animal modeling had escalated, especially in rodents, and become the mandatory method of demonstrating biological significance. Rats and mice both play a vital role in understanding the etiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology of neuropsychiatric diseases, and a careful examination of both organisms is necessary before a choice of model for a translational study can be made. Strains derived from Mus musculus and Rattus norvegicus are used in the inevitable majority of animal research for biomedical purposes [87]. Another frequently used technique is intracerebral cannula implantation, in which a small cannula is implanted into the brain. This can be used to locally administer a drug directly into a specific brain region, allowing the role of this brain region in a behavioral phenotype to be examined. More techniques for brain imaging in animals are being developed, based on functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography (PET). Rats have more benefits as compared to mice in cognitive tests, since rats, like humans, have six isoforms of the tau protein. Hyperphosphorylation of tau is involved in the formation of tangles, an essential pathological hallmark of AD, and the similarity in isoforms between humans and rats could indicate a higher degree of similarity in tangle formation as well [88]. There are two types of AD, including familial (5% of all AD) and sporadic, but the transgenic model does not show the complete model of AD, especially the sporadic form of AD, which accounts for 95% of AD cases. Agents such as colchicine, scopolamine, okadaic acid (OKA), streptozotocin, and trimethyltin are used to induce AD in animal model [89].

The Colchicine model

Colchicine is an alkaloid isolated from Colchicum autumnale having properties of anti-gout and anti-inflammatory actions. Decades later, it was used for preventing amyloidosis [89]. Colchicine blocks the axonal transport via depolymerization of MT and without inhibiting protein synthesis [90–92]. Colchicine is a cytotoxic agent that binds irreversibly to tubulin molecules and in result stops the aggregation of tubulin dimers to the fast-growing end, causing interruption of MT polymerization. By blocking axoplasmic transport, colchicine critically damages hippocampal granule cells, ultimately leading to neuronal loss, which manifests with cognitive impairment and spontaneous motor activity. Intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection (15 μg in 5 μL/7.5 μg in 10 μL) of colchicine in rats could induce AD-like pathology with consequent cognitive and behavioral alterations similar to AD [89, 93–95]. The drug selectively blocks acetylcholine transferase in the basal forebrain and hippocampus, which are regions responsible for memory [90]. When colchicine penetrates to the subarachnoid space, symptoms begin to show, including jumpy and irritable behavior, aggression, and loss of body weight. Colchicine administration induced lipid peroxidation, decreased glutathione (GSH) and acetylcholine levels in the brains of rats, and led to consequential oxidative damage resulting in cognitive impairment. Impairment of memory and neurodegeneration was characterized as a sporadic in the AD model after colchicine administration in rodents [89]. Decrease in appetite, and transient diarrhea, adipsia, and aphasia after 7–10 days of its administration are some of the limitations of colchicine-induced memory impairment [94].

The Scopolamine model

Scopolamine is a muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist that is practiced for cognitive dysfunction in experimental animals. Injection of scopolamine (1 mg/kg, 0.5 mg/kg intraperitoneal) raised cholinergic dysfunction and impaired cognition in rats [96–98]. Scopolamine is an anti-cholinergic drug that causes amnesia in humans and also impairs learning in animals. Hence, it is widely utilized as a model imitating human dementia in general and AD in particular [99]. Scopolamine caused reduced activity of choline acetyltransferase (the enzyme responsible for synthesis of acetylcholine in the cortex of AD patients. Scopolamine induced cerebral blood flow and glucose metabolism changes, which have been studied with PET and single photon emission-computed tomography. Scopolamine increased blood flow in the left orbitofrontal and the lateral occipital cortex regions bilaterally and decreased regional cerebral blood flow in the region of the right thalamus, the precuneus and the right and left lateral premotor areas [89]. ICV scopolamine-induced amnesia is connected with increased oxidative stress in structures associated with learning and memory. Oxidative stress, in turn, is a critical impairment factor leading to neuroinflammation and loss of cognitive function in AD [100]. This model has limitation that they fail to replicate the pathological aspects and the progressive degenerative nature of AD [101].

The Streptozotocin model

Streptozotocin (STZ) is synthesized by Streptomycetes achromogenes, soil bacteria. It was first used as an antibiotic and later used as an anticancer agent and drug therapy for neuroendocrine tumors [89, 102]. STZ, a glucosamine derivative of nitrosourea and preferentially toxic to pancreatic β-cells, being taken up via the glucose transporter Solute Carrier Family 2 Member 2, has been commonly used to induce diabetes in experimental animals [93]. In the periphery, STZ causes selective pancreatic β-cell toxicity due to the drug’s chemical structure which allows it to enter the cell via the GLUT2 glucose transporter. After peripheral administration, STZ causes alkylation of β-cell DNA which triggers activation of poly ADP ribosylation, leading to depletion of cellular NADH and ATP. When given intraperitoneally in high doses (45–75 mg/kg), STZ is toxic for insulin producing/secreting cells, which induces experimental diabetes mellitus type 1. Low doses (20–60 mg/kg) of STZ given intraperitoneally in neonatal rats damages IR and alters IR signaling and causes diabetes mellitus type 2 [7]. The mechanism of central STZ action and its target cells/molecules have not yet been clarified but a similar mechanism of action in the periphery has been recently suggested. GLUT2 may also be responsible for the STZ-induced effects in the brain, as GLUT2 also is reported to have regional specific distribution in the mammalian brain. ICV-STZ injection in rats has provided a relevant animal model for sporadic AD, as both the animal model and the human disease are characterized by progressive deterioration of cognition, oxidative stress, metabolic disorders, and insulin resistance [103]. Various studies have shown that injection of STZ (3 mg/kg) in rat brain results in cognitive decline, decreased brain weight, increased Aβ and tau levels in the hippocampus [89]. The central administration of STZ causes dysregulated brain insulin signaling and abnormalities in cerebral glucose utilization/metabolism accompanied by an energy deficit [104]. An experimental rat model was developed using STZ administered ICV in doses of up to 100 times lower (per kg body weight) than those used peripherally to induce an insulin resistant brain state [7, 105]. This model is specific for tau hyperphosphorylation.

The okadaic acid model

The OKA animal model is comparable to the STZ animal model. OKA, a polyether C38 fatty acid extracted from a black sponge, Hallichondria okadaii, has been extensively used, since it is a potent and selective inhibitor of the serine/threonine phosphatases 1 (PP1) and 2A (PP2A) and also, although at higher concentrations, of the Ca2 +/calmodulin-dependent PP2B (calcineurin) [93, 106, 107]. The reduced activity of PP2A has been linked with the pathology of AD and was supposed to be involved in hyperphosphorylation of tau [54]. ICVOKA injection develops memory impairment in rats, making it suitable for identification as a potential AD model. OKA caused lack of memory and elevation of Ca2 + that has a relationship with neurotoxicity. Increased intracellular Ca2 + resulted in the accumulation of Aβ, hyperphosphorylation of tau, and neuronal death [89]. ICV infusion of OKA (70 ng/day; for up to 4 months) could lead to some AD-associated pathologies including hyperphosphorylation of tau (at Ser-202/Thr-205) and apoptotic cell death within 2 weeks, as well as cortical deposition of non-fibrillar Aβ within 6 weeks of infusion. Formation of paired helical filaments of tau following intrahippocampal injection of OKA (1 mM, 0.5 ml); (1 μl bilateral infusion of 100 ng OKA) has been confirmed. It is noteworthy, that in this model, hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates do not develop into NFTs [93, 108]. Administration of OKA caused significant increase in PP2A, tau, Ca2 + calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, and Calpain mRNA expression in cerebral cortex and hippocampus in rats. Increased phosphorylation resulted in reduction of the normal tau stabilization of MT thereby leading to neuronal dysfunction [89].

Out of the above experimental models, STZ-induced AD is the best suitable model for inducing tau hyperphosphorylation which is one of the main hallmarks in AD. Taking care of the target site MTs and NFTs due to tau hyperphosphorylation, STZ-induced tau hyperphosphorylation is the appropriate animal model for tauopathy dementias (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pre-clinical experimental animal model using neurotoxin streptozotocin ethidium-mediated tau hyperphosphorylation

| S. No. | Dose and Route | Stereotaxic Co-ordinates | Key Points | Behavioral Parameters | Biochemical Parameters | Conclusion | Reference |

| 1 | ICV-STZ3 mg/kg bilaterally | AP: 0.8 mm ML: 1.5 mm DV: 4.0 mm |

•SIRT1 •Tau phosphorylation ERK1/2 •Streptozotocin |

Morris water maze test | •Western blotting •NAD/NADH ratio assay •Co-immunoprecipitation •Measurement activity of SIRT1 deacetylase |

•Inactivation of SIRT1, tau hyperphosphorylation,and memory impairment occurred in ICV-STZ-treated rats •Activation of SIRT1 by Resveratrol attenuated tau hyperphosphorylation and memory impairment via inhibiting ERK1/2 activity |

[238] |

| 2 | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg bilaterally Volume = 10 μl | AP: 0.8 mm ML: 1.5 mm DV: 3.6 mm |

•Xanthoceraside •Learning and memory •Hyperphosphorylated tau •PI3K, Akt, protein kinases •Phosphatases |

•Y-Maze test •Novel object recognition test |

•Western blot •Phosphorylation level of PI3K,GSK-3β,PP2A |

•Xanthoceraside has protective effect against learning and memory impairments •Inhibits tau hyperphosphorylationin the hippocampus through the inhibition of the PI3K/Akt-dependent GSK-3β signaling pathway and increases phosphatases activity. |

[239] |

| 3. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg bilaterally Volume = 0.5 μl/min | AP: –0.5 mm ML: 1.1 mm DV: –2.8 mm |

•AD •Streptozotocin •Nox2 •Cytokines |

Object recognition test | •Analysis of cytokines like IL-4,IL-1β,IL-2,10,IFN-γ,TNF-α,IL-12/23 •Nox2 mRNA expression evaluated by RT-PCR in hippocampus •Level of Ox-42 protein expression, a microglial cell marker. •Analysis of GFAP, an astrocyte marker •Level of 4-HNE during lipid peroxidation •Level of 3-NT,marker of oxidative damage induced by tyrosine nitration •Expression ofapoptosis-inducing factor |

•Nox2-dependent oxidative stress increase. •Nox2 deletion prevented tau phosphorylation, Aβ expression and decreased neuroinflammation in hippocampus |

[240] |

| 4. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg bilaterally Volume = 10 μl | AP: 0.8 mm ML: 1.5 mm DV: 4.0 mm |

•Adiponectin •Glycogen synthase kinase-3β •AD |

•Morris water maze test | •Golgi stain •Western blotting of Tau205, Tau396, Tau404 and Tau5, GSK-3β, GSK-3β (Ser9) and GSK-3β (Tyr216), Akt, p-Akt, PI3K and p-PI3K |

•Adiponectin supplements attenuate ICV-STZ-induced spatial cognitive deficits and tau hyperphosphorylation •Inactivate GSK-3β by increasingPI3K/Akt activity |

[241] |

| 5. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg bilaterally in both lateral ventricles | AP: 0.8 mm ML: 1.5 mm DV: 3.6 mm |

•ICV-STZ •Oxidative stress •Tau hyperphosphorylation •Tenuigenin |

Morris water maze test | •Nissl staining •Activities of SOD, glutathione peroxidase, and MDA in the hippocampus were measured |

•Western blotting: Analysis of 4-HNE protein and phosphorylated tau protein. •SOD activity, glutathione peroxidase, and malondialdehyde contents in the hippocampus were estimated. |

[242] |

| 6. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg bilaterally in both lateral ventricles Volume = 1 μl/ventricle | AP: 0.8 mm ML: 1.6 mm DV: 4.0 mm |

•Streptozotocin •Edaravone •Oxidative stress •Tau hyperphosphorylation |

•Balance beam test •Morris water maze test |

•Total protein assay •Nissl staining •Western blot was •used to assay the levels of 4-HNE protein adducts, tau, ser396- •phosphorylated tau and thr181-phosphorylated tau |

•The analysis of T-SOD, MDA,glutathione, H2O2 and OH, andprotein carbonyl levels were performed | [243] |

| 7. | ICV-STZ3 mg/kg bilaterally Volume = 10 μl on each site | AP: 0.8 mm ML: 1.5 mm DV: 4.0 mm |

•PI3K/Akt pathway •GSK-3β •Magnesium sulphate •Tau hyperphosphorylation |

•Morris water maze test | •Long term potentiation •Atomic absorption spectroscopy •Golgi staining •Immunohistochemistry •Real-Time Quantitative PCR •Western blotting •Protein expression of IR •Expression of postsynaptic PSD95, PSD93, GLUR1,GLUR2 •Level of GSK-3β,Akt •Expression of synapsin |

•GSK-3β and PP2A regulate tau phosphorylation. •ICV-STZ induces inactivation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and activation of GSK-3β and cause insulin desensitization. •Magnesium could promote the protein expression of IR,the mRNA levels of insulin and IRimproved synaptic efficacy, and prevented memory and learning impairments |

[244] |

| 8. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg bilaterally | AP: 0.8 mm ML: 1.5 mm DV: 4.0 mm |

•AD •AMPK •Diabetes mellitus Mitochondria tau |

•Morris water maze test | •Mitochondrial membrane potential, complex I •activity, and ATP levels assays •Western blotting- p-AMPK,Tau 5 and α-tubulin •Measurement activity of SIRT1 deacetylase •ROS measurement •SOD assay •Estimation of SOD, ROS, Mitochondrial membrane potential, complex I activity, and ATP levels assays |

•AMPK isa serine/threonine protein kinase maintainscellular energy balance in mammalian cells. •Reduction in AMPK inducestau hyperphosphorylation in ICV-STZ rats. •Restoring AMPK with its specific activator AICAR can attenuate mitochondria dysfunction, redox dysregulation, cleaved caspase-3, tau hyperphosphorylation, and cognitive impairment. |

[245] |

| 9. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg injected bilaterally Volume = 1.5 μl was injected in each hemisphere | AP: –0.5 mm ML: 1.1 mm DV: –2.8 mm |

•AD •Aβ •Neurofilaments •Streptozotocin •Synapsin •Tau protein |

Novel Object Recognition test | •Immunoblotting •Level of ChAT protein •Level of synapsin •Level of NF-L in hippocampus •Estimation of GSK-3β, tyrosineregulated kinase 1A, P25/cdk5, and MAPK, PP1, PP2A, and PP5 |

•Synapsin is a phosphoprotein related to synaptic vesicles. •Increase activity protein kinases such as glycogen synthase kinase 3β, dual-specific tyrosine regulated kinase 1A, P25/cdk5, MAPK have been observed in AD brains •Decrease in activity of phosphatases such as PP1, PP2A, and PP5, Aβ and increasephos phorylation of Tau, and decreased synapsin expression levels at 14 days after icv injection of STZ |

[246] |

| 10. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg bilaterally in both lateral ventricles Volume = 5 μl on each site | AP: 0.8 mm ML: 1.5 mm DV: 3.8 mm |

•AD •Naringenin •Aβ •Tau •PPARγ |

•Morris water maze test •Place navigation test •Body weight •Brain weight |

•Glucose measurements •Western-blot analysis- assess the levels of Tau, phospho-Tau, total GSK-3β, phospho-GSK-3β (ser9), IDE and β-actin •Immunohistochemical staining studies •Real-time quantitative RT-PCR=PPARγ and IDE were measured •Expression of AChE •Activity of GSK-3β |

•The balance between kinase and phosphatase activities determines the level of p-Tau. •GSK-3 is the S/T kinase that has two isozymes, GSK-3β and GSK-3α. •The GSK-3α regulates amyloidogenic processing of AβPP and GSK-3βkinase in PI3 K/AKT/GSK-3 signaling is regulated by insulin. GSK-3β regulates tau phosphorylation •Increased GSK-3β activity could promote the hyperphosphorylation of tau via inhibiting insulin signaling. |

[247] |

| 11. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg in one lateral ventricle, i.e., unilaterally Volume = 10 μl | AP: 0.8 mm ML: 1.5 mm DV: 3.6 mm |

•AD •Geniposide •Glucagon-like •peptide-1 receptor •Glycogen synthase kinase-3β •Tau hyperphosphorylation •Type 2 diabetes |

•Morris water maze test | •Immunohistochemistry •Western blot Assay •Observe PHF using TEM •Estimation of GSK-3β |

•GSK-3β is key regulator in glycogen synthesis. •Phosphorylation at tyrosine-216 in GSK-3β or tyrosine-279 in GSK-3α enhances the enzymatic activity, while phosphorylation of serine-9 in GSK-3β or serine-21 in GSK-3α decreases the activity. •Geniposide may serve as a GSK-3 inhibitor to exert its neuroprotective effect in the AD animal model. |

[248] |

| 12. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg unilaterally in left ventricle only Volume = 3 μl | AP: –1.0 mm ML: 0.3 mm DV: –2.5 mm |

•Streptozotocin 3xTg-ADmice •Cognitive deficits •Tau phosphorylation •Aβ •Synaptic proteins •Neuroinflammation •Insulin signaling |

•Elevated Plus Maze •Open field •One-Trial Object Recognition Task •Accelerating Rotarod Test •Morris water maze |

•Western blot analysis •Immunohistochemical staining •Levels of IR, insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor, insulin receptor substrate-1,PI3K, 3 phosphoinositide dependent protein Kinase-1, AKT, and GSK-3. |

•The 3xTg-AD mice develop numerous NFTs after the age of 12 months, but hyperphosphorylation of tau occurs at earlier age. •Tau phosphorylate at multiple phosphorylation sites in the 3xTg-AD mice at theage of 7–8 months. •STZ treatment causes increase in tau hyperphosphorylation and neuroinflammation, a insulin signaling dysfunction, decrease in synaptic plasticity. •Intranasal insulin treatment will improve cerebral glucose metabolism and cognition. |

[249] |

| 13. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg unilaterally in right lateral ventricle Volume = 10 μl | AP: –0.8 mm ML: 1.5 mm DV: –3.6 mm |

•Insulin signaling •Intranasal insulin •Tau hyperphosphorylation •Microglial activation |

•Open field test •Morris water maze |

•Western blotting •Immunohistochemical staining •Doublecortin evaluation •Evaluation of tau kinases, GSK-3, cdk5 and its activator p35, MAPK/ERK, JNK, and calcium/calmodulin- dependent protein kinase II |

•Intranasal delivery of insulin is a non-invasive technique that bypasses the blood-brain barrier and delivers insulin from the nasal cavity to the CNS via intraneuronal pathway. •Intranasal insulin restore the dysregulation of tau kinases in the hippocampus of ICV-STZ rats |

[250] |

| 14. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg bilaterally Volume = 10 μl in both ventricles | AP: 0.8 mm ML: 1.5 mm DV: 3.6 mm |

•AD •LX2343 •Cognitive deficits •Oxidative stress •Tauopathy •Mitochondria •GSK-3β inhibitor •Neuroprotection |

•Morris water maze test | •Mitochondrial membrane potential assay- mitochondrial membrane potential was determined •Mitochondrial function assay- concentration of ATP was measured •Transmission electron microscopy-based assay •GSK-3β enzymatic activity assay •Western blot-Cytochrome c estimationTUNEL assay- Cell death in animal brain tissue was detected •Immunohistochemistry- detect theexpression of P396-Tau protein |

•Protein levels of PSD95, synaptophysin, and vesicle-associated membrane protein 2, which are crucial for neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity, were detected by western blot. •Protective effect of LX2343 involves JNK/p38 pathway inhibition. |

[251] |

| 15. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg unilaterally in right lateral ventricle Volume = 5 μl | AP: 1.0 mm ML: 0.5 mm DV: 2.5 mm |

•AD •Liraglutide •Tau neurofilaments •Streptozotocin |

•Morris water maze test | •Western blot analysis-Protein concentration were measured •Microtubule binding assay •Immunohistochemistry staining-Detect NF and tau phosphorylation •Immunofluorescence staining- phosphorylation of NF-M/H detected by antibody SMI31 |

•Protein concentrations of the samples were measured by BCA Protein Assay Kit. •Microtubule binding assay tells about amount of tau and tubulin |

[252] |

| 16. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg bilaterally in both lateral ventricles | AP: –0.3 mm ML: –1.0 mm DV: –2.5 mm |

•AD •Astrocyte activation •FPR2 •Tau phosphorylation |

•Accelerating Rotarod test •Open field •Morris water maze |

•Western blot- Protein concentrations were determined •Immunofluorescence staining |

•FPR2 is known to be involved in host defense and inflammation. •As a receptor for Aβ, FPR2 could uptake and clear Aβ, suggesting a protective effect in brain. After being activated by Aβ, FPR could also induce glial cells to release proinflammatory factors, indicating its harmful effect on brain. •FPR2 deletion could improve cognitive function, hyperphosphorylation of tau, and the activation of astrocytes |

[253] |

| 17. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg bilaterally Volume = 2 μl/ventricle | AP: 0.8 mm ML: 1.5 mm DV: 3.6 mm |

•Memory deficit •Tau hyperphosphorylation •GSK-3β •PP2A •Streptozotocin •Hippocampus |

•Autoshaping Learning Task •Food Magazine and Autoshaping Training |

•Western blot-levels of p-tau, levels of p-GSK-3β estimated | •Insulin and IR are selectively distributed in the brain, including olfactory bulb, hypothalamus, cerebral cortex, amygdala and hippocampus. •IR expression is involved in memory formation. •Binding of insulin to IR induces activating signal transduction cascade of the PI3K pathway in turn activates Akt/PKB, which phosphorylate the GSK-3 results in its inactivation causing tau hyperphosphorylation. •Disruption of IR-PI3K-Akt/PKB signaling cascade leads to the dephosphorylation in Ser9 of GSK-3β confirming GSK-3β, a major kinase that phosphorylate in vivo tau in several sites; hyperphosphorylated in PHF. |

[254] |

| 18. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg bilaterally Volume = 1 μl/ min | AP: 0.8 mm ML: 1.4 mm DV: 3.6 mm |

•Nicotinamide •AD •SLN •Tau protein •PS |

•Spatial learning and memory test | •ELISA tests- calculate the total tau protein amount (T-tau) and phosphorylated tau 231 •Histopathology of animals brains-cresyl violetstaining used |

•Nicotinamide is ahistone deacetylase inhibitor. •The i.p. administration of nicotinamide loaded PS-SLN showed better memory improvement, preserved more neuronal cells and reduced the tau hyperphosphorylation in experimented animals comparing to its non-formulated conventional administration in the early stage of AD |

[255] |

| 19. | ICV-STZ 3 mg/kg bilaterally Volume = 5 μl/ventricle | AP: 0.8 mm ML: 1.5 mm DV: 3.6 mm |

•TMP •Memory impairment •GSK-3β •Tau hyperphosphorylation •Cholinergic neuron |

•Inhibitory avoidance task assay •Morris water maze assay |

•Western blot-Total protein concentration was determined •Analysis of cholinergic function- ChAT and AChE activity was measured spectrophotometrically |

•ICV-STZ, a good sporadic AD model causes spatial memory and fear memory impairments, impaired insulin signaling and overactivation of GSK-3β. •Activation of GSK-3β accounts for memory impairment, tau hyperphosphorylation, increased Aβ production, and neuroinflammation, all of which are hallmark characteristics of AD. •TMP was shown to decrease GSK-3β expression at both protein and RNA levels, and its analogue CXC195 could protect against cerebralischemia/reperfusion induced apoptosis through the PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β pathway. |

[256] |

4-HNE, 4-hydroxyl-2-nonenal; AChE, acetylcholinesterase; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; AKT, protein kinase B; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; APP, amyloid-β proteinprecursor; Aβ, amyloid-β; cdk5, cyclin-dependent kinase 5; ChAT, choline acetyltransferase; CNS, central nervous system; ERK, extracellular signal regulated kinase; FPR2, formyl peptide receptor 2; GSK, glycogen synthase kinase; ICV-STZ, intracerebroventricular streptozotocin; IDE, insulin degrading enzyme; IR, insulin receptor; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated proteinkinase; MDA, malondialdehyde; NF, neurofilaments; NFTs, neurofibrillary tangles; PHF, paired helical filaments; PI3K, phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; PS, phosphatidylserine; PSD, postsynaptic density protein; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SLN, solid lipid nanoparticle; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; TMP, tetramethylpyrazine.

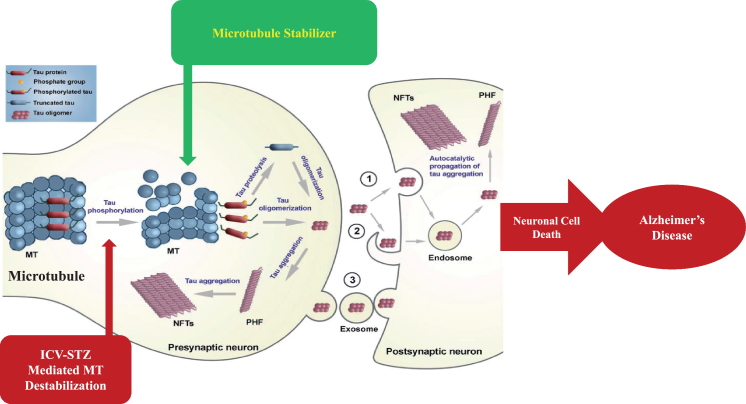

MICROTUBULE STABILIZATION, A PLAUSIBLE THERAPEUTIC TARGET SITE CENTERED BEHIND RESOLUTION OF AD

MTs are dynamic components of the intracellular neuronal cytoskeleton that alternate between polymerization and depolymerization phases forming polarized linear hollow tubing with diameter 24 nm extending their (+) ends facing toward the synapse and their (–) ends toward the cell body in the axons of neurons and composed of α-tubulin and β-tubulin heterodimers, which are micrometer long and play a role in maintenance of cell shape and transport of vesicles and organelles like mitochondria and cell division [109]. Axonal transport is carried out by two motor proteins kinesin and dynenins that transport cargo throughout neuron-like kinesin motors transport cargo toward axon terminals (anterograde) and dynein motors carry cargo away from axon tips (retrograde). For proper transport of neuronal contents and organelles, functional axonal MTs are required, and in many neurodegenerative diseases axonal transport is impaired in one way or another [110]. Tau is a class of proteins that are ample in nerve cells and perform the function of stabilizing the MT. In certain neuropathological situations, tau proteins become defective and fail to adequately stabilize the MT, which can result in MT destabilization further leading to detachment of tau from MT and being responsible for generation of abnormal masses known as NFTs that are toxic to neurons. NFTs are remarked in entorhinal cortex, limbic, and neocortex over the course of clinical progression in AD brains. Alterations in the stability of the MTs due to abnormal phosphorylation of tau proteins often precede damage to intracellular axonal transport that leads to neurotransmitter deficit [111]. The main challenge for this dementing disorder is to identify a preventive drug therapy that typically blocks the progression of AD. Moreover, in this review, we are focusing on one of the major pathological hallmarks of AD that is MT destabilization associated with NFT formed due to tau hyperphosphorylation, which may prove to be a preventive target in AD. There is availability of various treatment drugs for behavioral complications observed in AD. However, no particular drug therapy is showing remarkable improvement directly linked with tauopathy. Microtubule stabilizers (MTS) are potential neuroprotective agents to treat AD by restoring axonal function [109]. Therefore, involvement of MTS in prevention of tau abnormal phosphorylation may give hope for dementia patients. In Fig. 3, we present a schematic illustration of post-translational modifications of tau after inducing neurotoxin and use of an MTS as a plausible intervention to prevent MT destabilization.

Fig.3.

Schematic illustration of post-translational modifications of tau after inducing neurotoxin and microtubule stabilizer as plausible intervention to prevent microtubule destabilization.

CURRENT PHARMACOLOGICAL INTERVENTION FOR ALZHEIMER-TYPE DEMENTIAS

Drugs available clinically are for symptomatic relief only. No intervention is currently available as a preventive therapy. In the decades since Aβ and tau were identified, development of therapies for AD has primarily focused on Aβ, but tau has received more attention in recent years, in part because of the failure of various Aβ-targeting treatments in clinical trials [26, 112]. There are various therapeutic targets focusing which interventions are formed. The currently available treatment drugs include acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA receptor antagonists which are United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) approved. In order to ameliorate the disease, novel strategies have been developed [10]. In this regard, major focus is targeted to Aβ- and tau-based therapeutics, which is a major key to unlocking this disease in the near future. The various mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of AD create enough difficulty in producing an effective treatment. On the basis of different therapeutic targets as characterized in Fig. 4, interventions are prepared and their safety and efficacy are confirmed in different preclinical and clinical trials.

Fig.4.

Multifarious Target-based Intervention.

Tau-based therapies in clinical trials

Table 2 summarizes the pre-clinical and clinical data of recent tau-based therapies, phases of clinical trial, and related dose and route used in these trials. This review paper primarily focuses on deteriorating tau hyperphosphorylation, one of the main hallmarks of AD, so accumulating data of tau-related therapy is key. Instead of focusing on one hallmark, it also throws some light on ameliorating various pathogenesis consequences of AD by revealing new drug candidates focusing on other pathogenesis outcomes like neurotransmitter deficit, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation.

Table 2.

Post translational modified tau based interventions with preclinical and clinical status

| Tau based therapies | |||||

| S.no. | Intervention | Dose and route | Category | Mechanism of Action | Reference |

| 1. | Memantine | •2 mg/kg orally in Wistar rats •1 μM–5 μM in cell cultures |

Phosphatase Modifier | •N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist •Memantine enhances PP2A activity by blocking inhibitor 2. |

[257–260] |

| 2. | Sodium selenate | •1.5 μg/μL subcutaneous injection in mice •100 μM in cell culture •Phase IIa randomized trial, 30 mg/day orally |

Phosphatase Modifier | •Increases PP2A activity via activation of the regulatory B subunit and reduce sphosphorylation of tau | [261–263] |

| 3. | Acyclovir, Penciclovir, Foscarnet | 50 μM–100 μM in cell culture | Phosphorylated tau protein reducers | Target viral DNA replication. Inhibition of HSV1 DNA replication | [264–266] |

| 4. | Flavopiridol, Roscovitine | 5 μM and 50 μM | Kinase inhibitor, i.e., CDK5 | Compete with ATP for binding to CDK5, resulting in reduced activation of this kinase | [267–270] |

| 5. | Tideglusib | Phase IIa and b, 400–1000 mg/day orally | GSK-3β inhibitor | •Does not compete with ATP binding •Reduces tau phosphorylation, Aβ plaque burden, memory deficits, cell death, and astrocytosis |

[271–274] |

| 6. | Lithium chloride | 300 μg orally in AD patients Phase II | GSK-3β inhibitor | Lithium treatment significantly reduced phospho-tau levels in CSF and improved cognitive performance | [275–277] |

| 7. | Salsalate | •225 mg/kg in mice •Phase Ib 3,000 mg total daily by mouth |

Tau acetylation inhibitor | •Reduced p300 HAT activity •Inhibits acetylation of tau at Lys174 by p300 HAT |

[278, 279] |

| 8. | MK-8719 | •10–100 mg/kg in transgenic mouse model •Phase I 1200 mg orally |

Tau deglycosylation inhibitor O-GlcNAcase inhibitor | Inhibitor of the O-GlcNAcaseenzyme | [297, 280] |

| 9. | Methylthioninium chloride or Methylene Blue | 138 mg/day orally effective Higher dose 228 mg ineffective as causes decreases in red cell count and hemoglobinand increases in methemoglobin Discontinued for AD | Tau aggregation inhibitor | Blocks the polymerization of tau in vitro by trapping the tau monomers in an aggregation incompetent conformation | [281] |

| 10. | TRx0237 | •0.16 μM in cell culture •5–75 mg/kgorally in vivo •3 Phase III study 200 mg/day orally 150, 250 mg/day 200 mg/day Active Placebo –8 mg/day |

Tau aggregation inhibitor | •Reduced form of methylthioninium. •Blocks the polymerization of tau by trapping the tau monomers in an aggregation incompetent conformation |

[215, 282, 283] |

| 11. | TRx-0014 | NA | Tau aggregation inhibitor | Inhibitory properties for monoamine oxidase, nitric oxide production and as blocker of Tau aggregation | [26, 150] |

| 12. | Thiamet G | 500 mg/kg orally in mice | O-GlcNAcase inhibitor | Inhibition of O-GlcNAcase, the enzyme responsible for the removal of O-GlcNAc modification, shown to reduce tau pathology | [284] |

| 13. | Curcumin | 5 μM in N2a/APP695swe cells | P-Tau (ser404) /Tau expression suppressor | •Curcumin could inhibit the abnormal excessive phosphorylation of Tau byinactivating GSK-3 •Protect the nerve in AD through adjusting the cytoskeleton balance and maintain microtubule function |

[285] |

| 14. | Rolipram | Human trials fail after Phase II narrow therapeutic window and gastrointestinal adverse effects like emetic effect | PDE4 inhibitor | •Increases cAMP levels, enhances proteasome function and reduces the accumulation of tau •Reduce amounts of total and insoluble tau including phosphorylated tau |

[286–288] |

| 15. | BPN14770 | •Phase I 10 and 20 mg orally given twice day •Phase II is on the way to initiate |

PDE4 inhibitor | •Increases cAMP levels,enhances proteasome function and reduces the accumulation of tau •Reduce amounts of total and insoluble tau including phosphorylated tau |

[289, 290] |

| 16. | Bapineuzumab | •Phase II 0.15, 0.5, 1 mg/kg by intravenous infusion •Phase III had no effect on tau pathology |

Tau immunotherapy | Humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically targets these N-terminal residues ofAβ peptides and reduce tauhyperphosphorylation | [291, 292] |

| 17. | AADvac1 vaccine | •Transgenic rat given subcutaneous injection of (100 μg of peptide-KLH conjugate/dose) with PBS in a final dose volume of 300 μl •Phase II 40 μg Axon peptide 108 (coupled to KLH) using aluminum hydroxide (containing 0.5 mg Al3+) as adjuvant, in a phosphate buffer |

Anti-tau vaccine Active immunotherapy | NA | [215, 259, 293–295] |

| 18. | ACI-35 vaccine | •200 μL subcutaneous injection in mice •Phase I completed |

Anti-tau vaccine Active immunotherapy | •Contains antibodies that selectively bound pSer396/404 over the non-phosphorylated version of the epitope and could detect tau pathology by immunostaining. •Display a significant reduction in soluble tau phosphorylated at Ser396 but not at other amino acid residues |

[296, 297] |

| 19. | RG7345 | •30 mg/kg antibodyintraperitoneally •PhaseI trial and data is not released. Drug has been discontinued because of an unfavorable pharmacokinetic profile, because no safety or efficacy concerns seem to have been raised during the trial. |

Passive immunotherapy | Recognizes and bind to tau phosphorylated at Ser422, enter neurons and may potentially interfere with immunodetection of tau/pS422 by antibody and reduce tau pathology | [298, 299] |

| 20. | BMS-986168 | •60 mg/kg in mice •0.5–20 mg/kg in monkeys •Phase I IV infusion of 700, 2100, and 4200 mg |

Passive immunotherapy | •Humanized IgG4P monoclonal antibody that recognizes full length tau and N- terminal tau fragments which are secreted by neurons and found in extracellular interstitial fluid and CSF. •BMS-986168 mediates removal of e tau and reduces progression of disease. Total tau and free tau (not bound to BMS-986168) were measured |

[159, 300, 301] |

| 21. | ABBV-8E12 | •10 or 50 mg/kg intraperitoneal in mice •Phase I 2.5, 7.5, 15, 25, and 50 mg/kg intravenously •Phase II started |

Passive immunotherapy | Recognizes amino acids 25–30 of the tau protein and work extracellular reduced the levels of aggregated and hyper phosphorylated tauand improved cognition | [302, 303] |

| 22. | RO 7105705 | •3, 10, or 30 mg/kg in mice •Phase I IV dose of 225 mg–16.8 g; subcutaneous administration of 1,200 mg •Phase II is recruiting |

Passive immunotherapy | •Act primarily on pathological tau because it targets extracellular forms of the protein •Recognizes tau’s N-terminus and reacts with all six isoforms of human and primate tau, but not mouse tau |

[304, 305] |

| 23. | LY3303560 | •Phase I completed •Phase II is recruiting |

Passive immunotherapy | Bind and neutralize soluble tau aggregate | [306, 307] |

| 24. | JNJ-63733657 | Phase I recruiting | Passive immunotherapy | •Recognizes the mid-region of tau potentially interfere with cell-to-cell propagation of pathogenic, aggregated tau •Antibodies targeting the tau N-terminus and eliminate pathogenic tau “seeds” in a cell-based assay and inhibit spread of tau pathology |

[308, 309] |

| 25. | UCB0107 | 300 nM in cell culture | Passive immunotherapy | •Antibody binds to amino acids 235–246 in the proline-rich region of tau •Antibody was effective in preventing seeding and spreading of pathological tau |

[309, 310] |

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; Aβ, amyloid-β; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; GSK, glycogen synthase kinase; HAT, histone acetyltransferase; KLH, keyhole limpet hemocyanin; PDE4, phosphodiesterase 4; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A.

Anti-amyloid drugs in clinical trials

Mismetabolism of AβPP and the impaired clearance of Aβ generate a cascade of events including hyperphosphorylated tau mediated breakdown of microtubular assembly and resultant synaptic failure, leading to AD. Intracellular assembly states of the oligomeric and protofibrillar species may promote tau hyperphosphorylation, disruption of proteasome and mitochondria function, dysregulation of calcium homeostasis, synaptic failure, and cognitive dysfunction [113, 114]. Aβ generation from AβPP forms via a two-step proteolytic process involving β- and γ-secretases. The β-site AβPP cleaving enzyme (BACE1) first cleaves AβPP to produce a membrane bound soluble C-terminal fragment. A consequential cleavage of the C-terminal fragment by the γ-secretase activity further generates Aβ40 and Aβ42. Both types of peptide are found in amyloid plaques, but Aβ42 is evidently more directly neurotoxic and has a greater propensity to aggregate [113, 115]. Solanezumab, a vaccine acting on the soluble monomeric forms of the protein, did not significantly affect cognitive decline in a Phase III trial [116, 117]. Aducanumab, which is a human monoclonal IgG1 antibody anti-Aβ derived from an AD patient, was successful in a Phase Ib trial, and a Phase II trial is recruiting and the Phase III is active but not recruiting [118–120]. Gantenerumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody that binds aggregated Aβ and removes Aβ plaques by Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis, is in the Phase III recruiting stage [121, 122]. Some other monoclonal antibodies which are recently observed are BAN-2401 [123, 124]; UB-311 [125, 126]; Crenezumab [127, 128]; Ponezumab [129, 130]; Octagam [131, 132]; SAR-228810 [133, 134]; MEDI-1814 [135]; KHK-6640 [136, 137]; Lu-AF-20513 [138–140] and TTP4000 [133, 141]. Some approaches to inhibition of enzymes, i.e., β- and γ-secretases involved in AβPP cleavage, resulted in Aβ peptide formation. BACE1 is the β secretase implicated in AD and inhibitors of this enzyme are verubecestat MK8931 [142, 143]; AZD-3293(LY-3314814) [144, 145]; AtabecestatJNJ-54861911 [146, 147]; E-2609 [148]; BI-1181181 [145, 149]; inhibitor of γ-secretaseareEVP-0962 [150, 151]; and BMS-932481 [152]. Recently developed compounds which prevent aggregation of Aβ are GV-971 [153]; ALZT-OP1 [154]; Phenserine [155]; Posiphen [156, 157]; Scyllo-Inositol [158, 159]; ALZ-801 [160]; SAN-61 [161] and Exebryl-1 [162].

Anti-inflammatory drugs in clinical trials reducing inflammatory biomarkers

AD pathogenesis is not confined to the neuronal compartment but strongly interacts with immunological mechanisms in the brain. Misfolded and aggregated proteins bind to pattern recognition receptors on microglia and astroglia and initiate an innate immune response, characterized by the release of inflammatory mediators, which contribute to disease progression [163]. AAD-2004 is an inhibitor of the formation of cytokines that is in Phase I clinical trials [164]. Sargramostim enhances the microglial phagocytosis of Aβ and suppresses the generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and is now in Phase II clinical trials [165]. Angiotensin II, a key hormone peptide that binds to angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptors (AT1R and AT2R, respectively) expressed in neurons, microglia, and astrocytes, has pleiotropic roles in the brain, including mediation of inflammation [166]. Blockage of AT1R signaling directed the microglia toward a less pro-inflammatory stage [167]. Two antagonists of AT1R candesartan and telmisartan are now in Phase II clinical trials for AD [165, 167]. Purinoceptor 6 (P2Y6) is a purinergic receptor expressed on microglia that facilitates inflammation regulating microglial activation and phagocytosis. The uracil nucleotide uridine 5′-diphosphate is a specific ligand for P2Y6 receptor that can be released from damaged neurons to employ microglia to phagocytose cell debris [168]. GC021109, a small molecule reported to bind to P2Y6 receptor to stimulate microglial phagocytosis and inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine release from microglia, completed Phase Ia trials yielding positive results [165]. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) is a pattern-recognition receptor expressed on microglia and astrocytes that mediate pro-inflammatory or cytotoxic responses; it is also expressed on brain endothelial cells [169, 170]. RAGE is elevated in astrocytes and microglia in the hippocampus [171]. Azeliragon, a small antagonist of RAGE, has been evaluated in clinical trials [172]. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were one of the early classes of anti-inflammatory drugs subjected to AD drug development. The main actions of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are thought to be initiated through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) activity [173]. In several AD transgenic mouse models, levels of arachidonic acid, COX-2, and prostaglandins are elevated in the hippocampus [174, 175]. Ibuprofen and indomethacin exert their effects by acting as agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), while tarenflurbil (MPC-7869) and CHF5074 improve cognition and reduce brain inflammation [176–178]. Combination therapy of ibuprofen together with cromolyn (ALZT-OP1) targets the early stages of AD and ameliorates neuroinflammatory responses [165]. TNF-α mediates inflammation through binding with TNF receptor-1, which initiate the activation of NF-κB, JNK, and p38 MAPK signaling [179]. Etanercept functions as a decoy receptor for binding to TNF-α and inhibit TNF signaling. Phase II clinical trials of etanercept for AD did not significantly improve cognition or behavior [180]. Thalidomide inhibits the release of TNF-α in monocytes. Thalidomide not only inhibits TNF-α production by microglia and astrocytes, but also exhibits a neuroprotective effect in the hippocampus in an inflamed AD mouse model [181]. PPARγ is a nuclear hormone receptor that acts as a transcription factor in the regulation of inflammatory gene expression [182]. Agonists targeting PPARγ suppress the expression of proinflammatory genes. Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are agonists of PPARγ. Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone failed in Phase III clinical trials owing to a lack of efficacy [183]. Minocycline, an antibiotic that can permeate the BBB, exhibits anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects [184]. A recent trend in drug research is discovering the use of epigenetic drugs for AD treatment [185]. Two epigenetic drugs are currently undergoing clinical trials: ORY-2001 and vorinostat. ORY- 2001 is undergoing a Phase II clinical trial and is an epigenetic drug that selectively inhibits the activity of the lysine (K)-specific demethylase 1A and monoamine oxidase B [186]. Vorinostat, a histone deacetylase 2 inhibitor, is undergoing Phase I clinical trials [187]. Herpesviruses such as HSV-1, HHV-6A, and HHV-7 have been detected in the brains of AD patients and are concerned with the promotion of amyloid plaque deposition in AD progression [188, 189]. Valaciclovir, an antiviral drug, is undergoing two Phase II clinical trials for early AD treatment [190].

Antioxidant therapy reducing oxidative stress parameters

Oxidative stress is defined as the production of free radicals in a diseased state. This condition instructs the production of necessary antioxidants. Excessive free radicals occur in the case where there is a shortage of antioxidants [191]. The most prevalent antioxidants in the cell is glutathione, which exists as thiol-reduced (GSH) and disulfide-oxidized states. GSH can react with free radicals either independently or in the reaction catalyzed by glutathione peroxidase to form glutathione disulfide (GSSG), which can be converted back to the reduced state by glutathione reductase. The GSH/GSSG ratio is used as an indicator of cell redox potential and oxidative stress [192]. Other antioxidant enzymes are SOD and catalase, which catalyzes the disproportionation of superoxide to molecular oxygen and peroxide and the conversion of H2O2 to water and oxygen. The activity of these enzymes has been reported to be reduced in AD [193]. Several antioxidants, such as N-acetylcysteine, curcumin, resveratrol, vitamin E, ferulic acid, coenzyme Q (CoQ), selenium, and melatonin, have been tested for their potential to improve cognitive performance in healthy individuals [194–196]. Despite potent effects of these compounds on cellular oxidative status in vitro and in vivo, the convincing evidence of their therapeutic potential in humans is lacking. In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated the neuroprotective potential of CoQ10 in AD [197]. Idebenone, an analog of CoQ10, consists of short chains of isoprene units, crosses the BBB easily, is well tolerated in humans, and possesses good antioxidant properties [198]. Another potent antioxidant acting as an effective inhibitor of mitochondrial permeability transition pore is creatine. Creatine supplementation has been shown to protect against neuronal death caused by NMDA, malonate, Aβ, and ibotenic acid [199, 200]. Due to the importance of mitochondrial dysfunctions in the pathogenesis of various disorders, scientists have focused on the engineering of therapeutic molecules that could accumulate in mitochondria. One such therapeutic compound is MitoQ, which is the most widely used mitochondria-targeting antioxidant. MitoQ exhibits neuroprotection by scavenging peroxynitrite and superoxide and protects mitochondria against lipid peroxidation [201]. Another antioxidant, mitotocopherol, protects mitochondria from oxidative stress via inhibition of lipid peroxidation [202, 203]. MitoTEMPOL functions as a SOD mimetic [204].

APPROACHABLE DRUG THERAPY FOR ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE (TABLE 3)

Table 3.

Approachable drug therapy with their clinical and preclinical status in Alzheimer’s disease

| Drug | Clinical adverse effect | Mechanism of Action | Dose & Route Clinical | Pre-clinical | References Clinical | Pre-clinical |

| Donepezil (Memory enhancer) | Hepatotoxicity GI adverse events, bradycardia, nausea, diarrhea, insomnia, vomiting, asthenia/fatigue and anorexia, weight loss | AcetylcholinesteraseinhibitorAcetylcholine at cholinergic synapses | 5,10 mg orally;5,10,23 mg orally;10 mg orally;5,10, 23 mg orally;23 mg orally | 0.3 mg/kgp.o.;1 mg/kg i.p.;3 mg/kg i.p.;0.1, 0.3 mg/kg p.o.;1, 3 mg/kg i.p. | [311–315] | [316–319] |

| Memantine (Anti-excitatory) | Fatigue, pain, hypertension, dizziness, headache, constipation, vomiting, back pain, confusion, somnolence, hallucination, coughing, dyspnea, agitation, fall, inflicted injury, urinary incontinence, diarrhea, bronchitis, insomnia, urinary tract infection, influenza-like symptoms, abnormal gait, depression, upper respiratory tract infection, peripheral edema, anorexia, and arthralgia | NMDA receptor antagonistInhibit influx of Ca2 + ions | 20 mg orally;5, 10, 20 mg orally;10 &20 mg orally;5 &23 mg orally;10 &20 mg orally; | 20 mg/kg i.p.;5, 10 mg/kg i.p;10, 20 mg/kg i.p;0.1, 1 mg/kg i.p;30 mg/kg i.p. | [320–325] | [325–330] |

| Epothilone D (Microtubule stabilizer) | NA | Inhibit microtubule destabilizationIncrease polymerization of microtubules | 0.003,0.01, 0.03 mg/kg infusion; 0.003,0.01, 0.03 mg/kg infusion | 1, 3 mg/kg i.p.;1 mg/kg i.p;1,0.3,3 mg/kg i.p | [214, 215, 331, 332] | [210, 333–337] |