Abstract

An active 72-year-old man presented to the accident and emergency department (A&E) with odynophagia, dysphagia and haemoptysis 6 days after a minor operation and was discharged after treatment for an aspiration pneumonia. He presented to A&E 2 days later with worsening symptoms and was found to have dentures lodged in his larynx which were then removed in theatre. For 6 weeks after removal, he had periodic episodes of frank haemoptysis requiring multiple blood transfusions and, after extensive investigation, was found to have an erosion into an arterial vessel on his right parapharyngeal wall, just posterior to the glossopharyngeal sulcus. This case raises questions about perioperative care in patients with dentures, diagnostic decision-making in the emergency care setting and postoperative care after delayed removal of foreign bodies from the upper aerodigestive tract.

Keywords: anaesthesia; dentistry and oral medicine; ear, nose and throat/otolaryngology

Background

Full or partial dentures are used by approximately one in five people aged between 18 and 74 years.1 According to the literature, eating, maxillofacial trauma and dental treatment procedures are the main reasons for an aspirated tooth or denture,2–4 and while ethanol intoxication, dementia, stroke and epilepsy are predisposing factors, the majority of cases occur in patients with no known risks.2 3 Foreign bodies in the upper aerodigestive tract (UADT) can pose a diagnostic challenge, as the delayed symptoms may mimic other common conditions like asthma, recurrent pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infection and persistent cough.5

Endoscopic removal of foreign bodies in the aerodigestive tract using rigid scopes under general anaesthesia is considered the gold standard; however, there have been reports of patients requiring tracheotomy for removal.6 Complication rates from foreign body removal were not found to be related to method of removal but were associated with delayed removal (presentation >24 hours after symptoms onset), pharyngeal location, the foreign body being a fish bone and radiolucency.7 In older patients (aged >10 years), the most common complication is retropharyngeal abscess, followed by pulmonary complications (aspiration, pneumonia, pneumonitis, pulmonary collapse), local infection (oesophagitis, cellulitis, ulceration) and perforation. There is also a risk of bleeding secondary to granulation tissue or erosion into a major vessel but such a case has not yet been reported.8 At present, there is little advice regarding follow-up after removal of foreign bodies in high-risk cases. This case is important as it highlights a number of key learning points for anaesthetists, theatre staff, emergency physicians and ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeons alike.

Case presentation

This case report concerns an active 72-year-old retired electrician who lives independently with his wife, has never smoked and whose only medical history is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), well controlled with occasional salbutamol use.

He presented to the accident and emergency department (A&E) with odynophagia, dysphagia and haemoptysis 6 days after excision of a benign abdominal wall lump. He had not been able to swallow any solid food since his general anaesthetic. Oropharyngeal examination was normal, chest X-ray showed changes consistent with his COPD, haemoglobin was stable and inflammatory markers were mildly raised. He was treated for lower respiratory tract infection and concurrent pain secondary to intubation and discharged with clarithromycin, difflam mouthwash and a 5-day course of prednisolone.

He returned to A&E 2 days after this with worsening pain in his throat, ongoing haemoptysis, a hoarse breathy voice and being unable to swallow the medication he was discharged with. He was also feeling short of breath, particularly when lying down, and had taken to sleeping upright on the sofa. He was now requiring 2 L oxygen via nasal cannula to maintain his saturation. His chest X-ray showed some hazy opacification in the left hemithorax (see figure 1). He was admitted under the medics for aspiration pneumonia, who referred him to ENT on initial clerking. On ENT examination, the patient had a soft neck with full movement and no lymphadenopathy and a normal oropharynx. Flexible nasendoscopy examination revealed a metallic semicircular object overlying the vocal cords and completely obstructing their view. The object was pressed against the epiglottis and had caused erythema and swelling with evidence of erosion that was likely the cause of the haemoptysis. On explaining this to the patient, he revealed that his dentures had been lost during his general surgery admission 8 days earlier and consisted of a metallic roof plate and three front teeth. Lateral and anteroposterior neck X-rays revealed this to be the foreign body (see figures 2 and 3). He was taken to the emergency theatre where the dentures were removed. Postoperatively, his oxygen requirements continued to increase, so he was started on optiflow and continued treatment for an aspiration pneumonia. His oxygen was weaned, and he was discharged 6 days later.

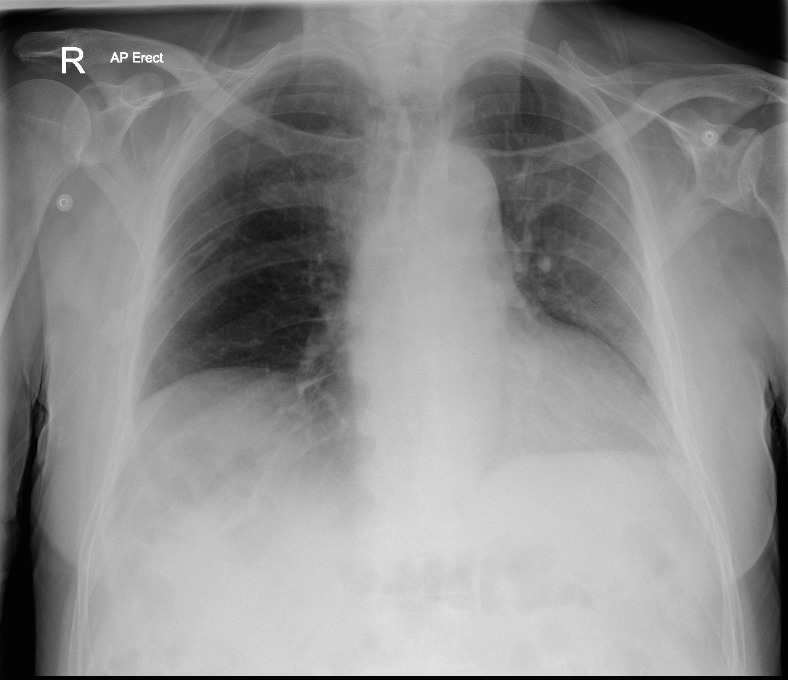

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior (AP) chest X-ray.

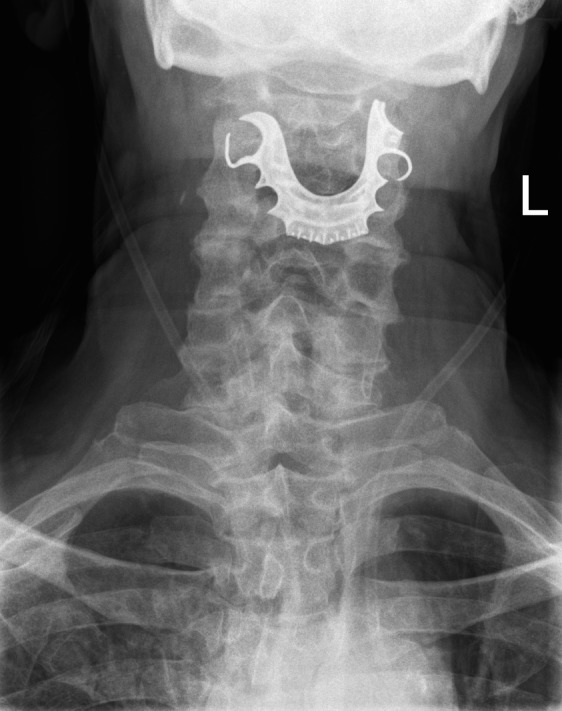

Figure 2.

Anteroposterior neck X-ray.

Figure 3.

Lateral neck X-ray.

Five days after discharge, the patient presented to A&E with sudden onset frank haemoptysis. His haemoglobin was stable at 136 g/L, and nasendoscopy showed granulation tissue at the right tongue base but no active bleeding, so he was discharged after a period of observation. Ten days later, he returned to the A&E with the same problem, estimating to have lost about 1.5 L of fresh red blood, with a haemoglobin of 109 g/L but no pain or malaena. Flexible nasendoscopy showed the same granulation tissue at the right tongue base but no active bleeding. Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy showed mild duodenitis but nothing to explain the bleeding, and CT angiogram of the neck and chest did not identify the bleeding site, so the patient was given tranexamic acid and discharged after 2 days. He returned to hospital again 6 days later with further haemoptysis, and this time, he was taken to the theatre for panendoscopy and found to have granulation tissue on his right parapharyngeal wall, just posterior to the glossopharyngeal sulcus, that bled on touching. This was felt to be the bleeding site, so bipolar diathermy was performed to the area. By this point, his haemoglobin had dropped to 73 g/L, so he was given a transfusion of 2 units of red blood cells and discharged 2 days later. Unfortunately, he returned 9 days later with further frank haemoptysis and was taken to the theatre as an emergency for pharyngoscopy. The same granulation tissue was noted, but when this was removed, it revealed a spurting arterial vessel. Attempts to clip and tie the vessel were unsuccessful, so the area was oversewn with vicryl, and surgicel was sutured over the area. He was given a further unit of red blood cells and discharged after observation.

Investigations

Blood work on his first presentation to the A&E showed stable haemoglobin at 161 g/L and mildly raised inflammatory markers with white cells of 11.2×109/L and C-reactive protein of 81 mg/L. He showed some evidence of dehydration with a urea of 11.7 mmol/L but normal creatinine and electrolytes. On return to A&E 2 days later, his haemoglobin remained stable but concentrated at 173 g/L, but his white cells had increased to 14.4×109/L and urea to 15.5 mmol/L.

Figure 1 depicts the chest X-ray after his second A&E attendance showing some consolidation in the left lower lobe consistent with an aspiration pneumonia. Figures 2 and 3 are the lateral and anteroposterior neck X-rays showing the position of the dentures in the larynx.

Other negative investigations were the oesophagogastroduodenoscopy which was important for exclusion, and CT angiogram which would have been more helpful in the context of active bleeding but was unfortunately not helpful in this case.

Differential diagnosis

The initial diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia was probably an accurate diagnosis, based on the chest X-ray, but certainly did not explain all his symptoms. When he returned with further haemoptysis and requiring oxygen, he was also investigated for a pulmonary embolism, but his D-dimer was found to be negative, so he was admitted under the medical team for the aspiration pneumonia. It was not until the medical team saw him, and he reiterated his presenting complaint of odynophagia and dysphagia, that ENT were asked to perform nasendoscopy, and the primary diagnosis was made.

Treatment

The initial treatment of the foreign body involved close teamwork between the anaesthetic team and the ENT surgeons. The patient was sedated and prepared for the worst-case scenario of an emergency tracheostomy with local anaesthetic and position markings; fortunately, this was not required. Awake nasal intubation was initially attempted, but this was not possible due to an obstructed view of the vocal cords. In the end, the foreign body was successfully removed by the ENT surgeon using a laryngoscope and Tilley’s forceps.

In the treatment of the bleeding point, medical management with tranexamic acid proved ineffective in the long term and while bipolar diathermy stopped the bleeding temporarily, the definitive treatment was to oversew with vicryl and stitch surgicel over the bleeding vessel.

Outcome and follow-up

On review a week after his final operation, the patient had not had any further bleeding, and nasendoscopy showed that the bleeding area was healing well. Six weeks later, he had not had any further admissions or attendances to A&E, and his haemoglobin was back up to 150 g/L.

Discussion

There have been documented cases of iatrogenic foreign bodies in the UADT in both dentistry9 and anaesthesia, including teeth,10 a latex glove11 and a denture that was aspirated into the larynx on intubation, in a case of bilateral maxillary fractures, which sadly ended in fatality after extubation.12 A 15-year review of 83 cases of aspirated dentures identified that in 12 (14%) cases the dentures were found in the hypopharynx or larynx, and in 6 (7%) cases the dentures were aspirated during general anaesthetic.3

There are no set national guidelines on how dentures should be managed during anaesthesia, but it is known that leaving dentures in during bag-mask ventilation allows for a better seal during induction,13 and therefore, many hospitals allow dentures to be removed immediately before intubation, as long as this is clearly documented.

In addition to reminding us of the risks of leaving dentures in during induction of anaesthesia when the Swiss cheese model of errors aligns, this case also highlights a number of important learning points. The first is to always listen to your patient. It has long been known that one gets the majority of the information needed to form a diagnosis based on the patients’ history; this was shown in a study of 80 patients where the final diagnosis was established after only the history in 82.5% of cases.14 However, with easy access to imaging and laboratory tests, we are all sometimes guilty of relying on these investigations. Although one should not underestimate the power of hindsight, looking back through this man’s A&E notes, he was clear that the reason he attended A&E was a sore throat and difficulty swallowing, and therefore, the positive findings on blood work and chest X-ray acted as a distraction. This concept is known as anchoring, a cognitive bias where a positive finding, such as consolidation on a chest X-ray, usually at the beginning or end of the decision-making process, alters our subsequent judgements so that other findings fit into the model we have created.15 Another relevant concept is something called ‘zebra retreat’ where a diagnostician retreats from making a correct diagnosis because of self-doubt about entertaining such a remote or unusual diagnosis.15 This is essential to prevent unnecessary investigations but occasionally results in situations like the one described in this report.

Learning points.

Presence of any dental prosthetics should be clearly documented before and after any procedure, and all members of the theatre team should be aware of the perioperative plan for them.

Listen to the story the patient is telling you and do not be distracted by positive findings on investigations.

High-risk foreign bodies in the upper aerodigestive tract, such as those that have been present for over 24 hours, should be closely monitored for complications.

Footnotes

Contributors: HAC planned, conducted and reported the work in this case report.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Redford M, Drury TF, Kingman A, et al. Denture use and the technical quality of dental prostheses among persons 18-74 years of age: United States, 1988-1991. J Dent Res 1996;75 Spec No:714–25. 75 Spec No:714–25 10.1177/002203459607502S11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Başoglu OK, Buduneli N, Cagirici U, et al. Pulmonary aspiration of a two-unit bridge during a deep sleep. J Oral Rehabil 2005;32:461–3. 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2005.01472.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kent SJ, Mackie J, Macfarlane TV. Designing for Safety: Implications of a Fifteen Year Review of Swallowed and Aspirated Dentures. J Oral Maxillofac Res 2016;7:e3 10.5037/jomr.2016.7203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mumoli N, Busoni A, Cei M, swallowed denture A. The Lancet 2009;373:1890 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60307-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gilyoma JM, Chalya PL. Endoscopic procedures for removal of foreign bodies of the aerodigestive tract: The Bugando Medical Centre experience. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord 2011;11:2 10.1186/1472-6815-11-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bist SS, Luthera M, Arora P, et al. Missing Aspirated Impacted Denture Requiring Tracheotomy for Removal. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol 2017;29:359–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Singh B, Kantu M, Har-El G, et al. Complications associated with 327 foreign bodies of the pharynx, larynx, and esophagus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1997;106:301–4. 10.1177/000348949710600407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Philip A, Rajan Sundaresan V, George P, et al. A reclusive foreign body in the airway: a case report and a literature review. Case Rep Otolaryngol 2013;2013:1–4. 10.1155/2013/347325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cameron SM, Whitlock WL, Tabor MS. Foreign body aspiration in dentistry: a review. J Am Dent Assoc 1996;127:1224–9. 10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dhadge ND. Tooth aspiration following emergency endotracheal intubation. Respir Med Case Rep 2016;18:85–6. 10.1016/j.rmcr.2016.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Warshawsky ME, Shanies HM, Dharawat M, et al. Endotracheal intubation-induced upper airway obstruction. Heart Lung 1996;25:69–71. 10.1016/S0147-9563(96)80015-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kroesen GA, Haid BC. Fatal complication from swallowed denture following prolonged endotracheal intubation: a case report. Anesth Analg 1976;55:438???439–9. 10.1213/00000539-197605000-00037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Conlon NP, Sullivan RP, Herbison PG, et al. The effect of leaving dentures in place on bag-mask ventilation at induction of general anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2007;105:370–3. 10.1213/01.ane.0000267257.45752.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hampton JR, Harrison MJ, Mitchell JR, et al. Relative contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and laboratory investigation to diagnosis and management of medical outpatients. Br Med J 1975;2:486–9. 10.1136/bmj.2.5969.486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bruno MA, Walker EA, Abujudeh HH. Understanding and Confronting Our Mistakes: The Epidemiology of Error in Radiology and Strategies for Error Reduction. Radiographics 2015;35:1668–76. 10.1148/rg.2015150023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]