Abstract

Essentially all cervical dysplasia is caused by human papilloma virus (HPV). Three HPV vaccines have been available, with Gardasil-9 being the most recently approved in the USA. Gardasil-9 covers high-risk HPV strains 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58 as well as low-risk strains 6 and 11. A 33-year-old woman (Gravida 2, Para 2) received Gardasil in 2006. Subsequently, her pap smear revealed low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. Cervical biopsies performed in 2015 and 2016 revealed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1 (CIN 1). She underwent loop electrosurgical excision procedure for persistent CIN 1, which demonstrated CIN 3. Genotyping revealed HPV type 56 infection. The advancement of Gardasil-9 vaccine only offers 90% protection to patients against HPV-related disease. Lay literature may mislead patients to think they have no risk of HPV infection.

Keywords: vaccination/immunisation, cancer - see oncology, cervical cancer, cervical screening, gynecological cancer

Background

Essentially all cervical dysplasia is caused by human papilloma virus (HPV). At least, 19 high-risk HPV types have been associated with cervical cancer with the most common types (16 and 18) encompassing 70% of cervical cancer cases.1 2

Gardasil (FDA approved: 2006) was the first HPV vaccine, offering protection against HPV strains 6, 11, 16 and 18. Gardasil-9, approved in the USA for use in 2014, includes HPV strains protected by Gardasil and strains 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58. With the introduction of HPV vaccinations, there has been a significant decrease in low grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) and cervical cancer in women.3 4 Although the vaccine has proven its effectiveness in reducing diseases caused by HPV, it has not completely eliminated the need for continued HPV surveillance.5

This case demonstrates possible limitations of HPV vaccines.

Case presentation

We present a 33-year-old woman (Gravida 2, Para 2) who received the HPV vaccine, Gardasil, in 2006, at age 21. She admitted to being sexually active prior to vaccination. The patient reported normal pap smears prior to receiving the vaccination. Subsequently, her pap smear revealed LSIL. She had cervical biopsies performed in 2015 and 2016, which demonstrated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1 (CIN 1).

TREATMENT

The patient underwent a loop electrosurgical excision procedure in 2017 due to repeat findings of CIN 1. The results demonstrated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 with clear margins of excision (figure 1). The lesion was HPV negative for types 16 and 18 but positive for ‘other high-risk HPV’ by the Cobas HPV assay (ROCHE). Subsequent genotyping revealed HPV type 56 infection (figure 2).

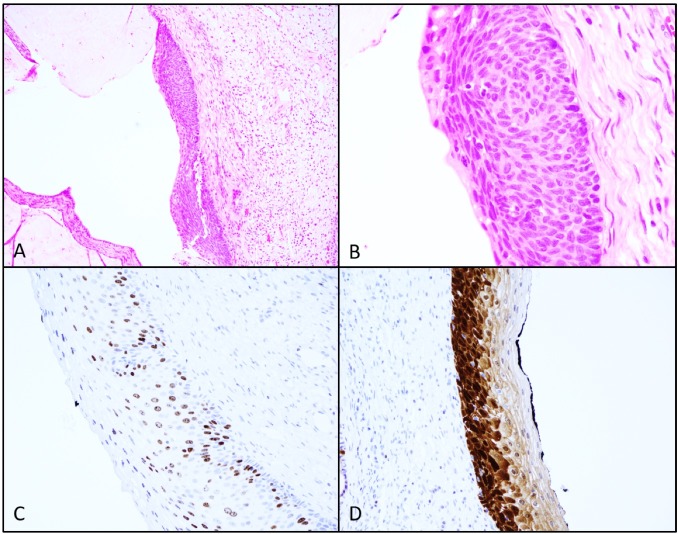

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs of H&E sections at 10x (A) and 40x (B), reveal dysplastic cells extending the full thickness of the epithelial surface consistent with CIN3. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for Ki-67 (C) and P16 (D) support the diagnosis.

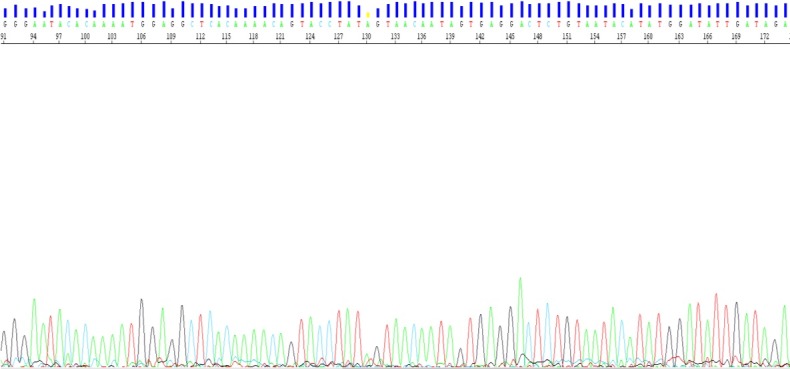

Figure 2.

Sanger sequencing of the L1 region of the human papilloma virus (HPV) genome consistent with HPV 56.

Outcome and follow-up

Repeat pap smears have been normal. The patient has been asymptomatic. No lesions were noted on speculum examination.

DISCUSSION

There has been a dramatic decrease in cervical dysplasia and cervical cancer with the introduction of HPV vaccines. However, the vaccination itself, is not a perfect solution. Our patient presented with CIN 3 and positive for HPV type 56. This strain, while listed as one of the 19 oncogenic HPV types, was not covered by the Gardasil vaccine, or the currently available Gardasil-9. This emphasises the limitations of vaccinations. Additionally, as the patient was vaccinated after the initiation of sexual activity, it is possible that she may have contracted the virus prior to vaccination. This further highlights the rationale from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Centre of Disease Control and Prevention for recommending the initiation of HPV vaccination as early as 9 years of age.6 Gardasil-9 covers seven high-risk HPV strains that are most strongly associated with cervical cancer making up approximately 90% of worldwide cases.1 However, there are 15–20 HPV strains that still have the capability to cause dysplasia and are not all covered under the vaccine.2

Few studies have shown the potential of cross protection of the HPV vaccine, specifically the bivalent and quadrivalent vaccines.7 8 These 2 types of vaccines have shown moderate cross protection against HPV strains 31, 45 and 52, which have now been included in the current Gardasil-9. However, our patient was found to have HPV strain 56; which despite receiving Gardasil, continues to demonstrate no additional protection with vaccination. Furthermore, with the reduction of strains covered by Gardasil-9, selective pressures may lead to uncovered HPV strains becoming more prevalent. Regardless of potential protection of the vaccine against strains not otherwise targeted, the data is limited and does not cover newer high-risk HPV strains.7

Public expectations lead by non-medical journals and possibly by physicians may give the impression that once immunised, the risk of cervical cancer is zero. Guidelines for vaccination prior to sexual activity will offer the patient maximum protection. However, screening protocols and healthcare providers must continue to reflect the possibility of disease with cervical screening even after vaccination.4 5

Healthcare providers must be vigilant in screening patients and in following-up patients, especially those who have had a positive screening in the past. Pap smear has limited specificity. Our patient had high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), which has a lesser chance of regression compared with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) or LSIL.2 The advancement of Gardasil-9 vaccine only offers 90% protection to patients against HPV- related disease.

Patient’s perspective.

Given my experience regarding my health, I can see how broken our healthcare services are especially with women’s health. Being part of the major healthcare groups, I am embarrassed at how difficult it is to schedule appointments and to receive good follow-up. For me to schedule my repeat pap smears, I had to call and leave multiple voicemails in order to schedule an appointment 6 months later. It is evident that there is a lack of staffing to accommodate for the population.

I was proactive with my health and instead sought out a private gynaecologist, who was able to cure me of my HSIL. The difference was night and day with scheduling appointments and the care I received. The passion my doctor has in serving others is evident when compared with the public health system.

Learning points.

Gardasil-9 vaccination covers human papilloma virus (HPV) strains that are accountable for about 90% of cervical dysplasia cases worldwide.

The 10% of HPV strains not covered by Gardasil-9 can still result in cervical cancer.

Despite the availability of HPV vaccination, physicians must encourage patients to continue screening protocols.

Footnotes

Contributors: BMcL, EV and KJC contributed in writing, editing portions of the manuscript. In addition, EV had also contributed in obtaining the pathological images. GW had done extensive background research and provided the background information, references as well as obtained medical records from the patient.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Zhai L, Tumban E. Gardasil-9: A global survey of projected efficacy. Antiviral Res 2016;130:101–9. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schiffman M. Integration of human papillomavirus vaccination, cytology, and human papillomavirus testing. Cancer 2007;111:145–53. 10.1002/cncr.22751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Villa LL. Overview of the clinical development and results of a quadrivalent HPV (types 6, 11, 16, 18) vaccine. Int J Infect Dis 2007;11(Suppl 2):S17–25. 10.1016/S1201-9712(07)60017-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baldur-Felskov B, Dehlendorff C, Junge J, et al. Incidence of cervical lesions in Danish women before and after implementation of a national HPV vaccination program. Cancer Causes Control 2014;25:915–22. 10.1007/s10552-014-0392-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yoshikawa H, Ebihara K, Tanaka Y, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16 and 18) vaccine (GARDASIL) in Japanese women aged 18-26 years. Cancer Sci 2013;104:465–72. 10.1111/cas.12106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Human papillomavirus vaccination. Committee Opinion No. 704. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:e173–8.28346275 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brotherton JML. Confirming cross-protection of bivalent HPV vaccine. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:1227–8. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30539-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ault KA. Human papillomavirus vaccines and the potential for cross-protection between related HPV types. Gynecol Oncol 2007;107:S31–3. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.08.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]