Abstract

The γ-crystallins of the eye lens nucleus are among the longest-lived proteins in the human body. Synthesized in utero, they must remain folded and soluble throughout adulthood to maintain lens transparency and avoid cataracts. γD- and γS-crystallin are two major monomeric crystallins of the human lens. γD-crystallin is concentrated in the oldest lens fiber cells, the lens nucleus, whereas γS-crystallin is concentrated in the younger cells of the lens cortex. The kinetic stability parameters of these two-domain proteins and their isolated domains were determined and compared. Kinetic unfolding experiments monitored by fluorescence spectroscopy in varying concentrations of guanidinium chloride were used to extrapolate unfolding rate constants and half-lives of the crystallins in the absence of the denaturant. Consistent with their long lifespans in the lens, extrapolated half-lives for the initial unfolding step were on the timescale of years. Both proteins’ isolated N-terminal domains were less kinetically stable than their respective C-terminal domains at denaturant concentrations predicted to disrupt the domain interface, but at low denaturant concentrations, the relative kinetic stabilities were reversed. Cataract-associated aggregation has been shown to proceed from partially unfolded intermediates in these proteins; their extreme kinetic stability likely evolved to protect the lens from the initiation of aggregation reactions. Our findings indicate that the domain interface is the source of significant kinetic stability. The gene duplication and fusion event that produced the modern two-domain architecture of vertebrate lens crystallins may be the origin of their high kinetic as well as thermodynamic stability.

Significance

Cataract is a highly prevalent disease of aging. It is characterized by the aggregation of proteins from the crystallin family in the cytoplasm of the cells of the eye lens. Lens opacity due to light scattering by these aggregates leads to loss of vision. Crystallins in the core region of the lens do not turn over and have therefore evolved to be highly soluble and stable for a lifetime. In the outer (cortical) region of the lens, some protein turnover does occur. Here, a detailed comparison of γD-crystallin, a kinetically stable abundant lens core protein, with γS-crystallin, which is abundant in the lens cortex and has lower stability, has revealed a mechanism by which lens crystallins adapted to an extremely long life.

Introduction

The transparency of the human eye lens depends on the properties of the α-crystallin and βγ-crystallin families of proteins, which are present in very high concentrations in the lens fiber cells. Crystallins comprise ∼90% of the total lens protein, ranging in concentration from 200 to 450 mg/mL in the elongated fiber cells (1, 2, 3). In the lens, α-crystallins provide a structural and passive chaperone function. The β- and γ-crystallins are thought to be primarily structural proteins, although refractive and redox functions have also been proposed (4, 5, 6). The β- and γ-crystallins are structurally similar, consisting of two domains with two intercalated Greek key motifs in each domain. γ-crystallins are monomeric, whereas β-crystallins can form oligomers (7, 8, 9, 10). Aggregation of partially unfolded or covalently damaged crystallins into high-molecular weight complexes leads to cataract disease, a progressive reduction in lens transparency due to light scattering by the growing aggregates (11, 12). This disease affects 17% of Americans over the age of 40 and is a large and growing healthcare issue for the aging population (13, 14, 15, 16, 17). In the absence of any approved therapeutic treatment, millions of cataract surgeries are performed every year in the U.S. alone, at a cost of billions of dollars (15, 16). Economically disadvantaged populations struggle to access and afford eye surgery, even in the United States (18, 19), and access is even more limited in many middle income and developing countries, so unoperated cataract remains the leading cause of blindness worldwide (16, 19).

To maximize transparency, the fiber cell in the core nuclear region of the lens are devoid of all organelles and do not support protein synthesis (20, 21). The crystallins present in the core of the lens, the oldest section, are synthesized in utero and then must remain folded and stable, resisting aggregation for a lifetime. Two abundant paralogous crystallins, γD and γS, share 69% sequence similarity and 50% sequence identity, have the same double Greek key fold, and are both ∼21 kDa in size (22, 23, 24). The thermodynamic stability of γD- and γS-crystallins and their isolated domains has been previously analyzed (25). Human γD-crystallin, concentrated in the oldest cells of the lens nucleus, has evolved to be one of the most thermodynamically stable proteins in humans; it has a melting temperature of ∼82°C and cannot be denatured by urea (26). γS-crystallin, concentrated in the younger cells of the lens cortex, where some protein turnover continues for at least part of life, is also thermodynamically stable but notably less so than γD-crystallin (25). However, in the absence of significant new protein synthesis, it is the kinetic stability—the unfolding rate of the stably folded native state—that is expected to be the biggest determinant of the rate of formation of partially unfolded intermediates that trigger aggregation. Understanding crystallin unfolding kinetics is critical for understanding, and perhaps delaying, the kinetics of cataract progression.

In this article, we compare the kinetic stability of γD (γDWT) and γS (γSWT) crystallin and their respective isolated domains. Equilibrium unfolding/refolding studies reported previously (27) indicated that γD-crystallin at intermediate concentrations of the denaturant guanidinium chloride populates an unfolding intermediate in which the C-terminal domain remains intact and the N-terminal domain is unfolded. Long molecular dynamics simulations of full-length γD-crystallin with explicit solvent and denaturant showed the same result (28). Isolated C-terminal domains of both γD- and γS-crystallins were more thermodynamically stable than their respective N-terminal domains (25). Surprisingly, kinetic unfolding experiments reported here using a variety of denaturant concentrations and extrapolation to the zero-denaturant condition revealed a crossover in the relative kinetic stability of the domains. We report that the N-terminal domains of both full-length proteins are expected to be more kinetically stable than their respective C-terminal domains in the absence of denaturant, despite their lower thermodynamic and kinetic stability as isolated domains. Our results are consistent with recent findings from force-induced denaturation (29). We propose that the integrity of the domain interface accounts for this difference and hence that the domain interface serves to kinetically stabilize the otherwise labile N-terminal domains for long-term aggregation resistance.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of constructs for wild-type and isolated domains

The γD and γS wild-type and isolated domains were cloned into the pQE1 His-tag containing vector (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The γDWT and γSWT consisted of G1–S174 for γD and S1–E177 for γS, respectively. The γDN consisted of residues G1–P82, and γDC consisted of residues R89–S174 (based on the numbering in Protein Data Bank [PDB]: 1HK0). The γSN consisted of residues S1–H86, and γSC consisted of residues Y93–E177 (PDB: IZWO).

Expression and purification of proteins

Recombinant full-length and variant proteins were prepared as described in Mills et al. (30). Briefly, all aforementioned vectors were transformed into Escherichia coli M15[pRep4] cells (QIAGEN), utilized for tightly regulated protein expression. The cells were lysed by conventional methods and purified by Ni-NTA resin (QIAGEN) affinity chromatography using a Pharmacia fast protein liquid chromatography apparatus. The purity and size of each protein was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. This purification protocol produced proteins with a purity of >90%. Protein concentrations were determined by unfolding proteins in 5.5 M GdnHCl and measuring absorbance at 280 nm using their respective protein extinction coefficients: for γDWT, γDN, γDC, γSWT, γSN, and γSC, 41,040 cm−1M−1, 20,580 cm−1M−1, 21,555 cm−1M−1, 41,040 cm−1M−1, 21,860 cm−1M−1, and 19,180 cm−1M−1, respectively.

Equilibrium unfolding and refolding

Equilibrium unfolding/refolding experiments were performed at 18°C. Folding and unfolding were determined by intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence, which is a reporter of domain core integrity, making use of the two buried Trp residues in the core of each domain (26). Each unfolding equilibrium sample consisted of 10 μg/mL protein with increasing concentrations of GdnHCl (0–5.5 M) in 100 mM sodium phosphate, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and pH 7.0 buffer (GdnHCl, 8 M; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). All samples were equilibrated for 24 h to reach equilibrium except for γDWT, which required a 192-h equilibration to reach equilibrium at 18°C. For equilibrium refolding experiments, a 10× protein solution was unfolded at 5.5 M GdnHCl for 5 h. The unfolded protein was then diluted 10-fold into various concentrations of GdnHCl (0–5.5 M), giving a lowest GdnHCl concentration of ∼0.55 M GdnHCl. Samples were excited at a wavelength of 295 nm. Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded from 310 to 400 nm, and buffer was corrected. Calculations of thermodynamic parameters were performed on 360 nm emission data and 360/320 nm emission ratio data using KaleidaGraph software version 4.0 (Synergy Software). Single wavelength 360 nm data were used to calculate m and ΔG values. Each experiment was repeated three times to determine averages and SD parameters.

Unfolding kinetics

Unfolding kinetic experiments were performed by first equilibrating 10× of purified protein in 100 mM phosphate, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, and pH 7.0 buffer at 18°C. Then, the protein sample was diluted 10-fold to a constantly agitated 3.5 or 5.5 M GdnHCl buffer using an injection port syringe feature with a dead time of ∼1 s. Temperature was maintained at 18°C, utilizing the circulating water bath feature. Each sample was excited at 295 nm, and the emission wavelength of 350 nm was recorded over time. The parameters for the fluorimeter were 10 nm bandpass for emission and excitation monochromators. Unfolded protein and native protein spectrum controls were recorded to ensure that the native state value was represented in the beginning of the experiment and that the protein was completely unfolded at the end of the experiment. The data were analyzed by fitting it to equations depicting two-state, three-state, or four-state models by KaleidaGraph 4.0 software. The best fit was determined by analyzing the most random residuals of the different fits. These experiments were repeated three times, and the data were averaged with SDs determined. Normalized fluorescence data are depicted to allow for comparison between various proteins.

Linear extrapolation of unfolding kinetics

Kinetic unfolding experiments were performed for each protein in various concentrations of GdnHCl at 18°C. The concentration of GdnHCl was above the equilibrium midpoints determined for each protein at 18°C. Natural logarithmic kinetic unfolding rate constants for different kinetic transitions were plotted versus the concentration of GdnHCl. A linear regression was fit between all points and extrapolated to the y axis using KaleidaGraph. The R-value of each fit was determined and is designated on each graph. The y axis intercept, the extrapolated unfolding kinetic rate constant in the absence of denaturant, was utilized to calculate the half-lives of each kinetic transition.

Results

Equilibrium unfolding/refolding experiments at different temperatures and equilibration times resulted in a hysteresis

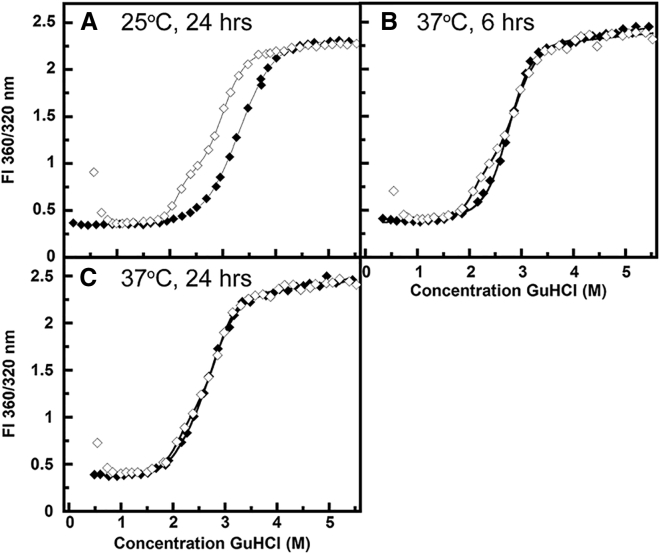

Previous equilibrium unfolding/refolding experiments with γDWT demonstrated distinct hysteresis under the initial equilibrium conditions of 25°C for a 24-h incubation time (Fig. 1 A). Under these conditions, both unfolding transitions required higher concentrations of GdnHCl than the refolding transitions. Increasing the temperature of equilibrium unfolding/refolding experiments to 37°C, with an equilibration time of 6 h, also demonstrated hysteresis in the first transition for unfolding, although less prominent than in a 25°C incubation (31) (Fig. 1 B). This first transition monitors the unfolding of the N-terminal domain of γDWT (32, 33, 34, 35). One explanation for this result is the presence of a kinetically controlled event along the unfolding pathway.

Figure 1.

Equilibrium unfolding (filled symbols) and refolding (open symbols) experiments of γDWT at different equilibration times and temperatures. Solid line indicates data fit. Note that the increasing signal values on refolding to dilute GuHCl are due to scattering from protein aggregates that form under these conditions (26). (A) This experiment replicates data first presented in (26)—24 h equilibration, 25°C; (B) 6 h equilibration, 37°C; (C) this control experiment replicates data presented in (25, 26)—24 h equilibration, 37°C.

If the unfolding transitions are kinetically controlled, an increase in incubation time would be expected to alleviate the hysteresis. When the incubation time at 37°C was increased to 24 h, the unfolding and refolding transitions were indistinguishable, indicating that the reaction had reached equilibrium (Fig. 1 C). These results suggested a kinetic barrier between the folded state and the previously identified partially folded intermediate consisting of the N-terminal domain unfolded and the C-terminal domain folded. The refolding transitions occurred at the same concentration of GdnHCl and were not altered by the change in incubation time (Fig. 1 C). Thus, hysteresis was attributable to unfolding kinetics.

In contrast to γDWT, γSWT did not exhibit a hysteresis at lower temperatures or at shorter equilibration times (data not shown). These results suggest that although both proteins are structurally similar, γSWT does not exhibit as large a kinetic barrier to the initiation of unfolding as γDWT. However, they do not preclude a kinetic barrier on a shorter timescale. The dilution of unfolded γD-crystallin chains from denaturing to nondenaturing buffer, or to low concentrations of denaturant, yields a turbid solution due to light scattering from high-molecular weight aggregates derived from the self-association of the refolding intermediates. The morphology of these aggregates are shown in (26).

Equilibrium unfolding/refolding of wild-type and isolated domain proteins

We next examined whether the equilibrium unfolding/refolding of the isolated domains exhibited hysteresis. These experiments were carried out at a lower temperature of 18°C for more direct comparison to the kinetic experiments described below. As with the results at 25°C, γDWT had a hysteresis with a more extensive separation between the equilibrium unfolding and refolding reactions. γDWT required incubation for 192 h (8 days) to achieve equilibrium at that temperature. In contrast, neither γSWT nor any of the isolated domains exhibited hysteresis after the 24 h of equilibration.

All four of the isolated domains as well as the full-length wild-type proteins demonstrated reversibility, indicating that they had the ability to unfold and refold at 18°C (Fig. 2). Upon refolding from denaturant, γDWT exhibited an off-pathway aggregation reaction at low GdnHCl concentrations, visible by light scattering, consistent with previous results at 37°C (26). The equilibrium unfolding of γDWT was best fit to a three-state model, indicating that an intermediate was still populated at 18°C, similar to the one previously observed at 37°C and assigned to the unfolding of the N-terminal domain in the context of the intact C-terminal domain. γSWT data were best fit to a two-state model demonstrating a more cooperative transition. All the isolated domains were best fit to two-state models. Differential thermodynamic stability was still displayed at the lower temperature. Likewise, the GdnHCl concentration midpoint (CM) increased about the same increment for every protein at 18°C compared to 37°C (Table 1). Taken all together, the properties of these proteins were comparable to the previous equilibrium unfolding/refolding experiments performed at 37°C (25, 30).

Figure 2.

Equilibrium unfolding (filled symbols) and refolding (open symbols) for γDWT (♦), γDN (●), γDC (▪), γSWT (▲), γSN (◢), and γSC (◣). Samples consisted of 10 μg/mL protein concentration, 100 mM sodium phosphate, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT (pH 7.0), and various concentrations of GdnHCl at 18°C. Equilibration time was 24 h, except for γDWT, which had an equilibration time of 192 h. All proteins excited at 295 nm and emission at 360 and 320 nm were calculated as a ratio. Equilibrium data fit indicated by solid black line.

Table 1.

Equilibrium Unfolding and Refolding Parameters for γD- and γS-Crystallin Wild-Type and Isolated Domains at 18°C

| Protein | Equilibrium Transition 1 |

Equilibrium Transition 2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMa |

Apparent m Valueb |

Apparent ΔG°N–I/Uc |

CMa |

Apparent m Valueb |

Apparent ΔG°N/I–Uc |

|

| 18°C | 18°C | |||||

| γDWT | 2.6 ± 0.035 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 10.5 ± 1.5 | 3.5 ± 0.02 | 2.9 ± 0.03 | 10.1 ± 0.2 |

| γDN | 1.6 ± 0.08 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 5.5 ± 1.3 | – | – | – |

| γDC | – | – | – | 3.2 ± 0.05 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 10.4 ± 0.7 |

| γSWT | 2.7 ± 0.04 | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 12.6 ± 2.0 | – | – | – |

| γSN | 2.12 ± 0.03 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 6.9 ± 1.7 | – | – | – |

| γSC | 2.7 ± 0.02 | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 9.6 ± 1.0 | – | – | – |

Transition midpoints in units of M GdnHCl.

Apparent m values in units of kcal∗mol−1∗M−1.

Free energy of unfolding in the absence of GdnHCl in units of kcal∗mol−1.

Unfolding kinetic analysis of the wild-type and isolated domain proteins

To understand the kinetic barrier that exists for γDWT, we tested individual domains to see if a large barrier to unfolding was associated with the N-terminal domain (γDN) as predicted, with the C-terminal domain (γDC), or with both domains. γSWT and its isolated domains (γSN and γSC) were compared to γDWT because equilibrium unfolding studies at a lower temperature and at shorter equilibration times did not exhibit an unfolding hysteresis. The unfolding kinetic experiments were performed using a fluorimeter equipped with an injection port; protein solutions were injected with a Hamilton syringe. The protein samples were injected into phosphate buffer containing GdnHCl, and tryptophan fluorescence emission after the dead time of ∼1 s was recorded. The conformational changes in the protein were tracked over time by fluorescence spectroscopy, preferentially exciting the tryptophan residues at 295 nm and measuring tryptophan fluorescence emission at 350 nm. During unfolding, native state quenching of these proteins is alleviated, causing an increase in tryptophan fluorescence emission (36, 37). To increase the time resolution of the unfolding of the isolated domains, all kinetic experiments were performed at 18°C, and kinetics were measured in independent experiments over a range of GdnHCl concentrations for each sample.

In kinetic unfolding experiments performed at 5.5 M GdnHCl, γDWT was extremely stable, requiring close to 3 h to reach an unfolded baseline (Fig. 3; Table 2). Under these conditions, the data fit to a three-state model, different from the four-state model reported previously (32). This discrepancy may be due to insufficient data to accurately fit the initial burst phase or because the first two transitions at this temperature are too similar to be resolved by our method. Using triple tryptophan mutants, Kosinski-Collins et al. showed that under denaturing conditions the γDN domain unfolded completely before the γDC domain unfolded (27). These results suggested the following unfolding reaction (Eq. 1):

| (1) |

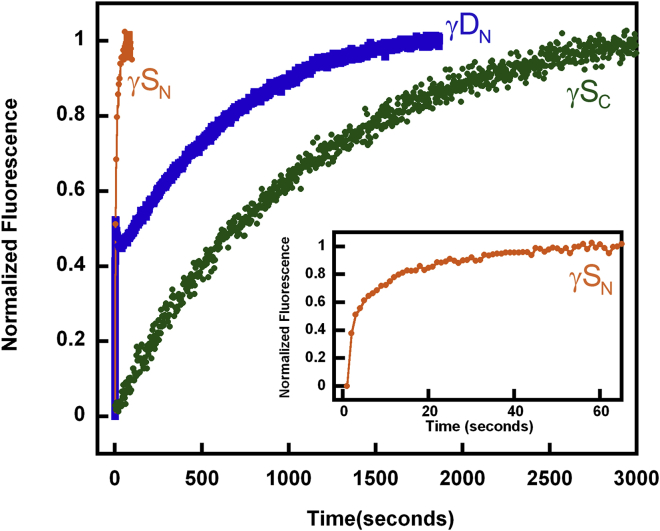

Figure 3.

Kinetic unfolding of γDWT and γSWT at 5.5 M GdnHCl at 18°C (top). Protein fluorescence emission at 350 nm was recorded every second unless otherwise noted, and all data were normalized for comparison. Inset is γSWT refolding kinetics on a shorter timescale to observe the kinetic transitions of γSWT (black ♦) and γDWT (black •). Shown is the kinetic unfolding of γDWT and γDC at 5.5 M GdnHCl at 18°C (bottom) (γDWT (black •), γDC (gray ▪)).

Table 2.

Kinetic Unfolding Parameters of γD and γS Wild-Type and Isolated Domain Proteins at 18°C

| Protein | Kinetic Unfolding (5.5 M GdnHCl) |

Kinetic Unfolding (3.5 M GdnHCl) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ku1a | ku2a | t1/2u1b | t1/2u2b | ku1a | ku2a | t1/2u1b | t1/2u2b | |

| γDWT | 0.003 ± 0.00095 | 0.0002 ± 5.2E−05 | 251 ± 111 | 3244 ± 944 | – | – | – | – |

| γDN | – | – | – | – | – | 0.0018± 6.8E–05 | – | 385 ± 14 |

| γDC | 0.00061 ± 6.3E−05 | – | 1143 ± 117 | – | – | – | – | – |

| γSWT | 1.39 ± 0.12 | 0.018 ± 9.6E−05 | 0.5 ± 0.04 | 37 ± 0.2 | 0.0023 ± 0.0003 | 0.00087 ± 0.0001 | 308 ± 34 | 804 ± 98 |

| γSN | – | – | – | – | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 0.08 ± 0.003 | 0.37± 0.1 | 9.1 ± 0.4 |

| γSC | 0.02 ± 0.002 | – | 33 ± 3 | – | 0.00074 ± 7.0E–05 | – | 937 ± 81 | – |

Kinetic unfolding rates in units of s−1.

Half-life in units of seconds.

For this pathway, ku1 represents the partial unfolding of the N-terminal domain, ku2 represents the complete unfolding of the N-terminal domain, and ku3 represents the complete unfolding of the C-terminal domain. In the experiments presented here, we suspect that ku1 and ku2 are hard to resolve at 18°C. The following equation for the two kinetic transitions (Eq. 2) provided an adequate fit:

| (2) |

The first unfolding transition, ku1, represents the complete unfolding of the N-terminal domain, and ku2 represents the complete unfolding of the C-terminal domain. The average half-life (t1/2) for these two kinetic transitions was 251 and 3455 s, respectively. γDC kinetic analysis was also performed at 5.5 M GdnHCl concentration, demonstrating a two-state transition, with a calculated average t1/2 of 1143 s (Fig. 3; Table 2).

In comparison, γSWT was completely unfolded within 3 min at 5.5 M GdnHCl concentration. The γSWT kinetic data were best fit to a three-state model, yielding one observable intermediate (Fig. 3, inset). The average calculated t1/2 for ku1 and ku2 were 0.5 and 37 s, respectively (Table 2).

At temperatures from 37 to 20°C, three of the isolated domains (γSC, γDN, γSN) unfolded partially or completely within the dead time of the experiment (∼1 s) in a 5.5 M GdnHCl solution. Thus, we studied these domains at 3.5 M GdnHCl (Fig. 4). This experiment demonstrated differential kinetic stability between the full-length γD and its isolated domains. Kinetic unfolding analysis at 18°C was not performed at lower GdnHCl concentrations for γDWT and γDC because these proteins do not completely unfold under those conditions. γSWT kinetic unfolding was performed at lower GdnHCl concentrations and was fit to a three-state model with a calculated average t1/2 of 308 s for the first kinetic transition and a t1/2 of 804 s for the second transition (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Kinetic unfolding at 3.5 M GdnHCl at 18°C. Shown are γSN (orange), γSC (green), and γDN (blue) (inset is the completion of γSC unfolding kinetics reaction). To see this figure in color, go online.

γSWT kinetic data at 3.5 M GdnHCl could also be fit to a two-state model; however, at higher concentrations of GdnHCl, the data exhibited a biphasic transition. Thus, the corresponding data in Fig. 3 were fit to a three-state model as well (Fig. 3). In other words, at the higher GdnHCl concentrations, the presence of an intermediate in γSWT was observable by a biphasic transition, a fast first phase and a slower second phase. At the lower GdnHCl concentration, the biphasic kinetic rate constants for the first and second phase represent only a twofold difference, indicating that at this lower concentration, the intermediate observed in the higher GdnHCl concentrations is not observable by this method. Fit residuals for both the two- and three-state models were similar.

Kinetic unfolding of γSC, γDN, and γSN yielded differential kinetic stability, with the hierarchy of stability from most stable to the least stable in that order. Kinetic unfolding of γSN, the least stable, was best fit to a three-state model with an average calculated t1/2 = 0.37 s for the first kinetic transition and 9 s for the second transition (Fig. 4; Table 2). Kinetic unfolding of γSC, the most stable, was similar to γSWT and was best fit to a two-state model with a t1/2 of 937 s (Fig. 4; Table 2). γDN fitting was more challenging because of a consistent rapid jump in fluorescence followed by a slower decrease in fluorescence within the first 50 s of the fluorescence emission trace (Fig. 4). Because of the reproducibility of this phenomenon, we suspect that it is a result of a short-lived structured intermediate in which the structure surrounding Trp42 and/or Trp68 is partially relaxed, resulting in less efficient quenching of the tryptophan fluorescence. The very efficient quenching of fluorescence from these tryptophans depends on intimate local interactions in the native state (33, 36, 37). Qualitatively, we can predict that this intermediate has a t1/2 of ∼25 s. To fit the rest of the kinetic data, the first ∼50 s of the data was deleted, and the remainder was fit to a two-state model (Fig. 4). This analysis yielded an average calculated t1/2 = 385 s (Table 2).

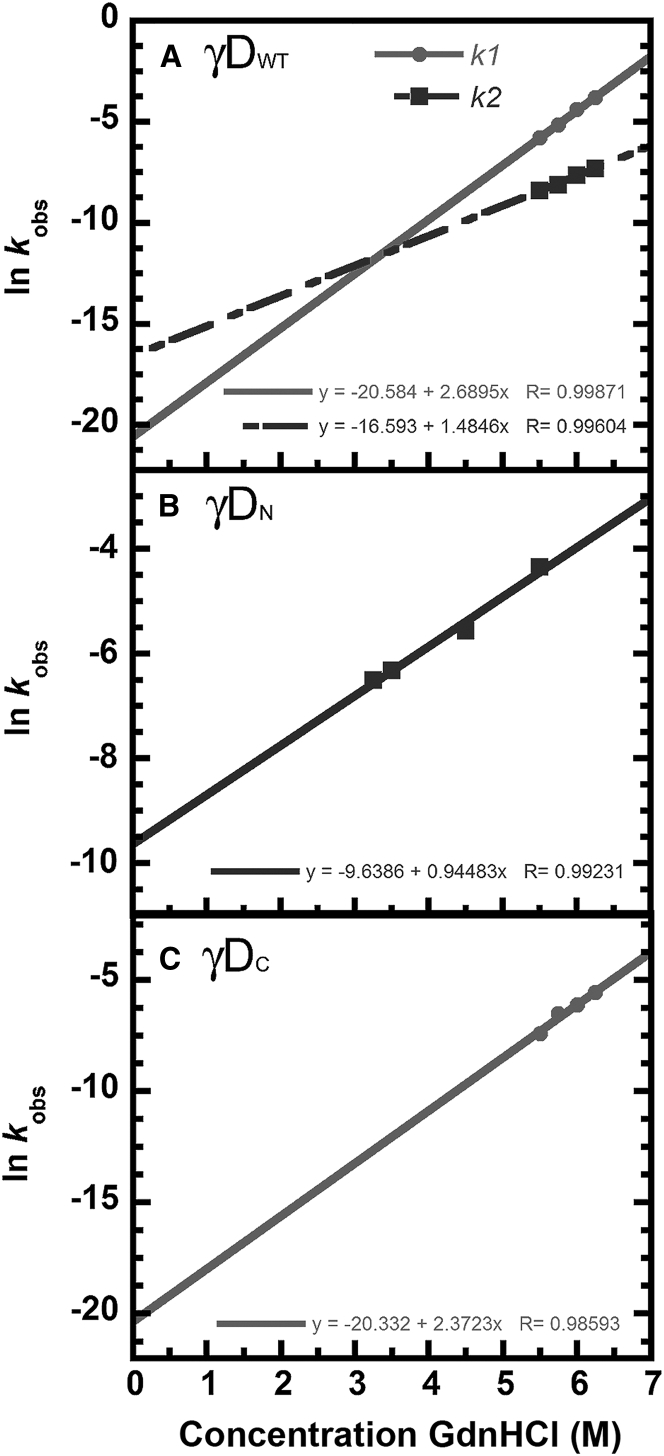

Extrapolation of unfolding rates predict slower spontaneous unfolding for γDWT than for γSWT

To estimate the kinetic stability under physiologically relevant conditions, we carried out kinetic unfolding experiments at various GdnHCl concentrations and extrapolated unfolding kinetic rate constants and half-lives to 0 M denaturant. This was done by plotting the logarithm of the unfolding kinetic rate constant versus denaturant concentration and extrapolating linearly to determine the kinetic rate constant with no denaturant, as reported in (31, 34). This “half-chevron” approach allows for comparison of all proteins to determine if, in a nondenaturing environment, the proteins maintain their differential kinetic stability (Figs. 5 and 6). All experiments were performed at 18°C to obtain comparable kinetic unfolding data for all proteins. Based on the extrapolated rate constants in the absence of denaturant, γDWT was the most kinetically stable with a t1/2 of 19 years for the first kinetic transition (ku1) and t1/2 of 129 days for the second kinetic transition (ku2). The γSWT extrapolated values were 1.6 years for the first kinetic unfolding transition and ∼2 days for the second kinetic unfolding transition under these conditions (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Linear extrapolations of kinetic unfolding rate constants versus GdnHCl concentration for γDWT and its individual domains. All experiments consisted of 10 μg/mL protein concentration, 100 mM sodium phosphate, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, pH 7.0 buffer, and defined concentrations of GdnHCl at 18°C. (A) γDWT, (B) γDN, and (C) γDC are shown.

Figure 6.

Linear extrapolation of kinetic unfolding rate constants versus GdnHCl concentration for γSWT and its individual domains. All experiments consisted of 10 μg/mL protein concentration, 100 mM sodium phosphate, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, pH 7.0 buffer, and defined concentrations of GdnHCl at 18°C. (A) γSWT, (B) γSN, and (C) γSC are shown.

Table 3.

Linear Extrapolated Unfolding Rate Constants and Half-Lives of γD and γS Wild-Type and Isolated Domains at 18°C

| Protein | Kinetic Unfolding Transition 1 |

Kinetic Unfolding Transition 2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ku1H2Oa | t1/2H2Ob | ku2H2Oa | t1/2H2Ob | |

| γDWT | 1.15 E–09 | 19.1 years | 6.22 E–08 | 129 days |

| γDN | – | – | 6.52 E–05 | 2.95 h |

| γDC | 1.48 E–09 | 14.9 years | – | – |

| γSWT | 2.36 E–08 | 1.62 years | 3.93 E–06 | 2.04 days |

| γSN | 0.009 | 1.3 min | 0.0004 | 26.6 min |

| γSC | 2.66 E–06 | 3 days | – | – |

Kinetic rates in units of s−1.

Half-life in various units: days, days; hrs, hours; min, minutes; yrs, years.

Surprisingly, linear extrapolation of both γDWT and γSWT unfolding rates revealed much steeper slopes for the first transitions than for the second transitions. For instance, for γSWT, there was a ∼600-fold decrease in the first transition rate constant from 5.5 M GdnHCl to 3.5 M GdnHCl but only a 20-fold decrease in the second transition rate constant (Table 2; Fig. 6). This indicates that the concentration of GdnHCl had a stronger effect on the first transition than the second transition. Lack of complete unfolding at lower GdnHCl concentrations constrained our available denaturant concentration range for γDWT; nonetheless, the first kinetic rate constant decreased sevenfold from 6.25 M GdnHCl to 5.5 M GdnHCl, whereas the second rate constant showed only and a threefold decrease (Fig. 5). These large differences in the slope lead to crossovers in the relative domain stability such that the N-terminal domain is less stable than the C-terminal domain at high denaturant concentrations but more kinetically stable at zero denaturant.

The kinetic stability hierarchy among the isolated domains was γDC > γSC > γDN > γSN. The extrapolated t1/2 for the unfolding of γDN (past the initial 50 s of data) was ∼3 h—almost five orders of magnitude lower than in the context of the full-length protein. By contrast, γDC had an extrapolated value of ∼15 years, which is actually higher than the second unfolding transition of the full-length protein (Table 3). The situation was similar for γSWT isolated domains, except for its overall lower kinetic stability. The t1/2 for the first kinetic transition of γSN was 1.3 min and the t1/2 for the second transition was 26.6 min (Table 3)—again nearly five orders of magnitude less than for the first unfolding transition of the full-length protein γSWT. Here, too, γSC was more kinetically stable than γSN and had a t1/2 of 3 days, which is slightly higher than for the full-length protein’s second unfolding transition.

It should be noted that all extrapolated values are approximations and not meant to portray precise values for these proteins in their native environment, especially because the experiments were performed at 18°C and not 37°C. In addition, traditionally, chevron plots are not analyzed for multistate kinetic proteins because the presence of an intermediate is not guaranteed under all conditions; we assumed that unfolding still follows a three-state model in the absence of denaturant. Previous studies of apomyoglobin have used fluorescence spectroscopy to monitor kinetics and extrapolated multistate kinetic values to no denaturant (35). Furthermore, the differential kinetic stability between full-length proteins and their isolated domains is consistent between γSWT and γDWT. The large increase in kinetic stability of both N-terminal domains in the context of the respective full-length proteins, compared to the isolated domains, warrants explanation. We attribute this difference to the domain interface, which has already been shown in γDWT to contribute ∼4 kJ/mol of thermodynamic stability to the N-terminal domain (25).

Discussion

High kinetic stability assists in the survival of proteins in harsh conditions or prevents accumulation of an aggregation-prone conformer. It is conferred by a large activation energy barrier between the folded native states and partially folded intermediates or the unfolded state. For example, the bacterial extracellular protease, α-lytic protease, requires high kinetic stability to remain stable in its harsh environment and to resist self-proteolysis (38, 39, 40). Transthyretin, a human plasma protein, utilizes kinetic stability to promote the formation of its tetrameric state and to prevent an altered monomer conformation that is a precursor to amyloid formation (41, 42, 43). High kinetic stability for unfolding has been observed, though not quantitatively measured, in bovine γF-crystallin and βB2-crystallin (44, 45). Quantitative kinetic unfolding experiments have been performed with microbial crystallins, Protein S from Myxococcus xanthus and spherulin 3a from Physarum polycephalum. These proteins have a similar Greek key fold as the β- and γ-crystallins and may be ancestors of the lens crystallins, although this relationship has not been unambiguously confirmed (46). Protein S and spherulin 3a both have high conformational and kinetic stability that increases upon binding Ca2+, as do many other microbial βγ-crystallins (47).

It has been suggested that this high stability is due to the complex topology of the β- and γ-crystallin Greek key fold (44). As reported here, however, the two C-terminal domains are similar in thermodynamic stability (ΔG’s of ∼10 kcal∗mol−1) but very different in kinetic stability, with t1/2 of 14 years for γDC versus 3 days for γSC, despite identical fold topology. This topology includes the intercalated double Greek key domains, the interdomain interface and linker, and in some cases, a tyrosine corner in each double Greek key domain. γS-crystallin is thought to be evolutionarily divergent from the other γA-F-crystallins (48). In the human lens, γA-D-crystallin genes are expressed early in lens development and thus are mostly localized in the nuclear region of the lens (49). However, there is evidence that γS-crystallin gene expression increases after birth and is therefore more prevalent in the cortical regions of the lens (49, 50). The differential temporal expression and spatial localization of crystallins is thought to influence the overall refractive properties of the lens, but it also likely influences the degree of evolutionary pressure toward high kinetic stability.

The evolutionary pressure for high kinetic stability of the native state is likely much stronger in lens crystallins, which must resist misfolding and aggregation over many decades, than for most other proteins, which turn over throughout life. Folding/unfolding hysteresis in proteins is rare in general and typically reflects complex topology and adaptation to extreme kinetic stability (51). In virtually all cases, human lens crystallins have been found to be more thermodynamically stable than cow, mouse, or rat homologs (1, 52, 53)—further evidence that their stability is an adaptation to prolonged lifespan. The distinct hysteresis observed in the equilibrium unfolding/refolding transitions of γD-crystallin reflects a high barrier to the initiation of unfolding. On the other hand, γS-crystallin did not demonstrate hysteresis and was less kinetically stable than γD-crystallin. These results suggest that γD-crystallin, localized to the oldest region of the lens, evolved a stronger interdomain interface, increasing its kinetic as well as thermodynamic stability (25).

We propose that the domain interface is the major stabilizing factor that accounts for the dramatic difference between the N-terminal domain’s kinetic stability as an isolated domain versus within the context of the full-length protein. Interactions at the domain interface have been shown to increase the thermodynamic stability of one or both domains in mammalian βγ-crystallins (53, 54, 55) as well as in microbial and plant ones (56, 57, 58). Notably, kinetic stabilization of domain cores in the full-length Protein S has been attributed to the interface between its two domains (59), and a mutation within the domain interface was shown to kinetically stabilize γD-crystallin in acid urea (60). The domain interface is known to contribute significantly to the thermodynamic stability of the N-terminal domain of human γD-crystallin under denaturing conditions (25, 32). However, both statistical (61) and molecular dynamics (28, 62) simulations have shown that the domain interface is easily disrupted under denaturing conditions (high temperature, chemical denaturant, or destabilizing mutation). This may account for the observed hysteresis in N-terminal unfolding (Fig. 1). When the protein begins in nondenaturing buffer, and then denaturant is added, the intact domain interface dramatically slows N-terminal unfolding; by contrast, when the protein starts in denaturing buffer, the N-terminal domain lacks this stabilizing interface, and its kinetic stability likely reverts to a value close to that of the isolated domain. Thus, we predict that integrity of the domain interface is critically important for the kinetic stability of the N-terminal domain core under physiological conditions.

Previous results have demonstrated sequential unfolding of the two domains in γDWT, with the N-terminal domain unfolding first under denaturing conditions (27), and our results are consistent with that initial report. Under denaturing conditions, thermodynamic and kinetic stability is lower for the isolated N-terminal domain of either protein than for the respective C-terminal domain (see Table 2; (25)). This is also true for the relative kinetic stabilities of isolated N- and C-terminal domains in the absence of denaturant (Table 3). Surprisingly, however, the reverse is true in the context of the full-length protein once extrapolated to zero denaturant (Table 3). When it is in the context of the full-length protein, kinetic stability of the N-terminal domain increases by several orders of magnitude compared with that of the isolated domain, whereas the C-terminal domain’s kinetic stability does not increase and even decreases slightly. Lower kinetic stability for the C-terminal domain in the context of the full-length γDWT was recently observed by single-molecule force spectroscopy (29), although mechanical force may not be the most relevant denaturant in the context of lens proteins.

Our findings led us to a model that may seem counterintuitive at first glance; the N-terminal domain in the full-length protein is more kinetically stable than the C-terminal domain in the absence of denaturant, but as soon as the C-terminal domain unfolds, the N-terminal domain loses its extreme kinetic stability (Fig. 7). This model follows logically if the domain interface is indeed the origin of the observed high kinetic stability. We refer to this phenomenon as “kinetic stapling”; it may be related to the observation in force spectroscopy that certain structural elements, though mechanically weak, are not stress bearing during the early steps of unfolding and hence unfold only after more mechanically stable elements.

Figure 7.

Models of γDWT and γSWT unfolding under no denaturant conditions as mixtures of isolated domains (A) or the full-length proteins (B), illustrating how domain fusion alters the unfolding landscape. Linear extrapolation data suggests that the unfolding of the N-terminal domain has a high kinetic barrier to unfolding in the full-length proteins, in sharp contrast to the isolated domain. Predicted half-time for the first transition in each scenario is noted.

The order of unfolding of the γ-crystallin domains within the full-length proteins under physiological conditions warrants further investigation. The only available in vivo data are indirect. Proteomic studies of aged human lenses revealed multiple truncations in γD-crystallin in both domains, but with a preponderance of C-terminal truncations (63, 64). This observation, however, may be due to rapid degradation or aggregation of the N-terminal domain once it unfolds, whereas the C-terminal domain may tolerate some truncations. Notably, a truncated fragment corresponding to the intact isolated C-terminal domain of γD-crystallin has been found in the lens (65), but no intact N-terminal domain has been found; this is consistent with the above hypothesis if the unfolding of the truncated N-terminal domain leads to aggregation or to further degradation that “trims” the protein down to the more stable C-terminal domain.

The high kinetic stability of the N-terminal domain in the context of the full-length protein has likely been selected as a protective mechanism against aggregation. Point mutations in the γ-crystallins that cause congenital cataract cluster strongly in the N-terminal domain (12), and cataract development is strongly associated with the formation of non-native disulfide bonds that kinetically trap partially unfolded aggregation-prone intermediates within the N-terminal domain (66). In vitro, the oxidation-mimicking Trp42Glu substitution in the N-terminal domain of full-length γDWT results in greater destabilization and more rapid and robust aggregation than the homologous mutation in the C-terminal domain (67). Once destabilized and partially unfolded, the Cys-rich N-terminal domain can act as a disulfide sink for strained but kinetically favorable disulfides formed in the C-terminal domain (6, 61). Studies of covalent damage in the domain interface in vitro suggest that they are deleterious to the stability and solubility of the γD, βB2, and βB1-crystallins (32, 55, 68, 69). Aggregation induced by a metal, Zn(II), has also been shown to target the N-terminal domain and perhaps to require misfolding (70, 71). Integrity of the domain interface in γ-crystallins may thus be of critical importance in preventing or delaying aggregation via the N-terminal domain and resulting cataract. Lanosterol was recently proposed as a possible treatment for cataract (72), although its efficacy requires further study (73). It is intriguing that recent simulations suggest lanosterol binding may rescue the melted domain interface (74).

Unfolding half-times of the lens γ-crystallins need not be equal the lifespan of these proteins to maintain transparency because these proteins are capable of refolding back to the native state without the assistance of chaperones (26). However, when refolding from a fully denatured state, aggregation occurs (26). At least in the case of force-induced denaturation and refolding, the culprit was found to be domain swapping of the N-terminal β-hairpins (29). However, the evolutionary transition of βγ-crystallins from single domain to duplicated-domain proteins confers a significant advantage because the domain interface may act as an internal chaperone to promote refolding in the rare event that unfolding has occurred. Refolding rates of either domain, even isolated, are significantly higher than unfolding rates, making it highly unlikely that both domains of the dimer will unfold simultaneously. As long as one domain remains folded, its side of the domain interface is available to template proper folding of the other.

Vertebrate two-domain βγ-crystallins likely evolved from single domain ancestors, such as that present in the urochordate sea squirt, Ciona intestinalis (75), via a gene duplication and fusion event (76). Later evolution of the γ-crystallin lineage may have tuned the domain interface to increase kinetic stability of the N-terminal domain, prolonging lens transparency in step with increasing lifespan. The β-crystallin family may have pursued an alternative strategy. MacDonald et al. showed that a mutation near the interface of rat βB2 N-terminal domain (C50F) caused an increase in the kinetic barrier to unfolding (44). The Cys 50 residue in the N-terminal domain of βB2 is implicated in the subunit exchange to form homo- and heterodimers with itself and other β-crystallins, contributing to the polydispersity of the crystallins. Therefore, in this case, it appears that the interface-derived kinetic barrier was lessened in favor of oligomer formation.

Author Contributions

I.A.M.-H., S.L.T., and J.A.K. conceptualized and designed the research. I.A.M.-H., S.L.T., and M.S.K.-C. carried out the research. I.A.M.-H., S.L.T., M.S.K.-C., E.S., and J.A.K. analyzed the data. I.A.M.-H., E.S., and J.A.K. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yongting Wang, Jiejin Chen, Ligia Acosta, Xiaonan Lin, and Robin Nance for helpful discussions and/or technical assistance. The Biophysical Instrumentation Facility for the Study of Complex Macromolecular Systems (National Science Foundation-0070319 and National Institutes of Health (NIH) GM68762) is gratefully acknowledged.

This work was supported by an NIH grant GM17980 awarded to J.A.K. I.A.M.-H. was supported by a United Negro College Fund Merck Dissertation Graduate Fellowship and S.L.T. by a Cleo and Paul Schimmel Graduate Fellowship. E.S. was supported by NIH grant GM126651.

Editor: David Eliezer.

References

- 1.Bloemendal H., de Jong W., Tardieu A. Ageing and vision: structure, stability and function of lens crystallins. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2004;86:407–485. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wride M.A. Lens fibre cell differentiation and organelle loss: many paths lead to clarity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2011;366:1219–1233. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michael R., Bron A.J. The ageing lens and cataract: a model of normal and pathological ageing. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2011;366:1278–1292. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao H., Brown P.H., Schuck P. The molecular refractive function of lens γ-crystallins. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;411:680–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khago D., Bierma J.C., Martin R.W. Protein refractive index increment is determined by conformation as well as composition. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2018;30:435101. doi: 10.1088/1361-648X/aae000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serebryany E., Yu S., Shakhnovich E.I. Dynamic disulfide exchange in a crystallin protein in the human eye lens promotes cataract-associated aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:17997–18009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werten P.J., Lindner R.A., de Jong W.W. Formation of betaA3/betaB2-crystallin mixed complexes: involvement of N- and C-terminal extensions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1432:286–292. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bateman O.A., Lubsen N.H., Slingsby C. Association behaviour of human betaB1-crystallin and its truncated forms. Exp. Eye Res. 2001;73:321–331. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lampi K.J., Oxford J.T., Kapfer D.M. Deamidation of human beta B1 alters the elongated structure of the dimer. Exp. Eye Res. 2001;72:279–288. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takata T., Woodbury L.G., Lampi K.J. Deamidation alters interactions of beta-crystallins in hetero-oligomers. Mol. Vis. 2009;15:241–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreau K.L., King J.A. Protein misfolding and aggregation in cataract disease and prospects for prevention. Trends Mol. Med. 2012;18:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serebryany E., King J.A. The βγ-crystallins: native state stability and pathways to aggregation. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2014;115:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Eye Institute Cataract. 2010. https://www.nei.nih.gov/eyedata/cataract

- 14.Lukatsky D.B., Shakhnovich B.E., Shakhnovich E.I. Structural similarity enhances interaction propensity of proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;365:1596–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tielsch J.M., Kempen J.H., Friedman D.S. Vision problems in the U.S.: prevalence of adult visual impairment and age-related eye disease in America. Prevent Blindness America. 2008 http://www.visionproblemsus.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y.C., Wilkins M., Mehta J.S. Cataracts. Lancet. 2017;390:600–612. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30544-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Resnikoff S., Felch W., Spivey B. The number of ophthalmologists in practice and training worldwide: a growing gap despite more than 200,000 practitioners. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2012;96:783–787. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Word Health Organization Blindness and vision impairment. 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment

- 19.Wang W., Yan W., He M. Cataract surgical rate and socioeconomics: a global study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016;57:5872–5881. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bassnett S. Lens organelle degradation. Exp. Eye Res. 2002;74:1–6. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bassnett S. On the mechanism of organelle degradation in the vertebrate lens. Exp. Eye Res. 2009;88:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basak A., Bateman O., Pande J. High-resolution X-ray crystal structures of human gammaD crystallin (1.25 A) and the R58H mutant (1.15 A) associated with aculeiform cataract. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;328:1137–1147. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00375-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Z., Delaglio F., Bax A. Solution structure of (gamma)S-crystallin by molecular fragment replacement NMR. Protein Sci. 2005;14:3101–3114. doi: 10.1110/ps.051635205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sagar V., Chaturvedi S.K., Wistow G. Crystal structure of chicken γS-crystallin reveals lattice contacts with implications for function in the lens and the evolution of the βγ-crystallins. Structure. 2017;25:1068–1078.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mills I.A., Flaugh S.L., King J.A. Folding and stability of the isolated Greek key domains of the long-lived human lens proteins gammaD-crystallin and gammaS-crystallin. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2427–2444. doi: 10.1110/ps.072970207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosinski-Collins M.S., King J. In vitro unfolding, refolding, and polymerization of human gammaD crystallin, a protein involved in cataract formation. Protein Sci. 2003;12:480–490. doi: 10.1110/ps.0225503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kosinski-Collins M.S., Flaugh S.L., King J. Probing folding and fluorescence quenching in human gammaD crystallin Greek key domains using triple tryptophan mutant proteins. Protein Sci. 2004;13:2223–2235. doi: 10.1110/ps.04627004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das P., King J.A., Zhou R. Aggregation of γ-crystallins associated with human cataracts via domain swapping at the C-terminal β-strands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:10514–10519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019152108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Manyes S., Giganti D., Fernández J.M. Single-molecule force spectroscopy predicts a misfolded, domain-swapped conformation in human γD-crystallin protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:4226–4235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.673871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flaugh S.L., Kosinski-Collins M.S., King J. Contributions of hydrophobic domain interface interactions to the folding and stability of human gammaD-crystallin. Protein Sci. 2005;14:569–581. doi: 10.1110/ps.041111405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schellman J.A. Selective binding and solvent denaturation. Biopolymers. 1987;26:549–559. doi: 10.1002/bip.360260408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flaugh S.L., Mills I.A., King J. Glutamine deamidation destabilizes human gammaD-crystallin and lowers the kinetic barrier to unfolding. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:30782–30793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen J., Toptygin D., King J. Mechanism of the efficient tryptophan fluorescence quenching in human gammaD-crystallin studied by time-resolved fluorescence. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10705–10721. doi: 10.1021/bi800499k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schellman J.A. The thermodynamic stability of proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1987;16:115–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.16.060187.000555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baryshnikova E.N., Melnik B.S., Bychkova V.E. Three-state protein folding: experimental determination of free-energy profile. Protein Sci. 2005;14:2658–2667. doi: 10.1110/ps.051402705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen J., Flaugh S.L., King J. Mechanism of the highly efficient quenching of tryptophan fluorescence in human gammaD-crystallin. Biochemistry. 2006;45:11552–11563. doi: 10.1021/bi060988v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J., Callis P.R., King J. Mechanism of the very efficient quenching of tryptophan fluorescence in human gamma D- and gamma S-crystallins: the gamma-crystallin fold may have evolved to protect tryptophan residues from ultraviolet photodamage. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3708–3716. doi: 10.1021/bi802177g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cunningham E.L., Jaswal S.S., Agard D.A. Kinetic stability as a mechanism for protease longevity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:11008–11014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cunningham E.L., Agard D.A. Interdependent folding of the N- and C-terminal domains defines the cooperative folding of alpha-lytic protease. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13212–13219. doi: 10.1021/bi035409q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaswal S.S., Sohl J.L., Agard D.A. Energetic landscape of alpha-lytic protease optimizes longevity through kinetic stability. Nature. 2002;415:343–346. doi: 10.1038/415343a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colon W., Kelly J.W. Partial denaturation of transthyretin is sufficient for amyloid fibril formation in vitro. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8654–8660. doi: 10.1021/bi00151a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lai Z., McCulloch J., Kelly J.W. Guanidine hydrochloride-induced denaturation and refolding of transthyretin exhibits a marked hysteresis: equilibria with high kinetic barriers. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10230–10239. doi: 10.1021/bi963195p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson S.M., Wiseman R.L., Kelly J.W. Native state kinetic stabilization as a strategy to ameliorate protein misfolding diseases: a focus on the transthyretin amyloidoses. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005;38:911–921. doi: 10.1021/ar020073i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacDonald J.T., Purkiss A.G., Slingsby C. Unfolding crystallins: the destabilizing role of a beta-hairpin cysteine in betaB2-crystallin by simulation and experiment. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1282–1292. doi: 10.1110/ps.041227805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Das B.K., Liang J.J. Thermodynamic and kinetic characterization of calf lens gammaF-crystallin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1998;23:191–197. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(98)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bagby S., Harvey T.S., Ikura M. Structural similarity of a developmentally regulated bacterial spore coat protein to beta gamma-crystallins of the vertebrate eye lens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:4308–4312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srivastava S.S., Mishra A., Sharma Y. Ca2+-binding motif of βγ-crystallins. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:10958–10966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.O113.539569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wistow G. The human crystallin gene families. Hum. Genomics. 2012;6:26. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su S., Liu P., Chen S. Proteomic analysis of human age-related nuclear cataracts and normal lens nuclei. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52:4182–4191. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-7094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wistow G., Sardarian L., Wyatt M.K. The human gene for gammaS-crystallin: alternative transcripts and expressed sequences from the first intron. Mol. Vis. 2000;6:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andrews B.T., Capraro D.T., Jennings P.A. Hysteresis as a marker for complex, overlapping landscapes in proteins. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:180–188. doi: 10.1021/jz301893w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Purkiss A.G., Bateman O.A., Slingsby C. Biophysical properties of gammaC-crystallin in human and mouse eye lens: the role of molecular dipoles. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:205–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wenk M., Herbst R., Jaenicke R. Gamma S-crystallin of bovine and human eye lens: solution structure, stability and folding of the intact two-domain protein and its separate domains. Biophys. Chem. 2000;86:95–108. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(00)00161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palme S., Slingsby C., Jaenicke R. Mutational analysis of hydrophobic domain interactions in gamma B-crystallin from bovine eye lens. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1529–1536. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lampi K.J., Amyx K.K., Steel E.A. Deamidation in human lens betaB2-crystallin destabilizes the dimer. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3146–3153. doi: 10.1021/bi052051k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wenk M., Baumgartner R., Mayr E.M. The domains of protein S from Myxococcus xanthus: structure, stability and interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;286:1533–1545. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wenk M., Jaenicke R. Calorimetric analysis of the Ca(2+)-binding betagamma-crystallin homolog protein S from Myxococcus xanthus: intrinsic stability and mutual stabilization of domains. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;293:117–124. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Clout N.J., Kretschmar M., Slingsby C. Crystal structure of the calcium-loaded spherulin 3a dimer sheds light on the evolution of the eye lens betagamma-crystallin domain fold. Structure. 2001;9:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00573-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wenk M., Jaenicke R., Mayr E.M. Kinetic stabilisation of a modular protein by domain interactions. FEBS Lett. 1998;438:127–130. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sahin E., Jordan J.L., Roberts C.J. Computational design and biophysical characterization of aggregation-resistant point mutations for γD crystallin illustrate a balance of conformational stability and intrinsic aggregation propensity. Biochemistry. 2011;50:628–639. doi: 10.1021/bi100978r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Serebryany E., Woodard J.C., Shakhnovich E.I. An internal disulfide locks a misfolded aggregation-prone intermediate in cataract-linked mutants of human γD-crystallin. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:19172–19183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.735977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong E. 2018. Modeling the structure and dynamics of gamma-crystallins and their cataract-related variants. PhD thesis (University of California Irvine) [Google Scholar]

- 63.Srivastava O.P., Srivastava K. Degradation of gamma D- and gamma s-crystallins in human lenses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;253:288–294. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Srivastava O.P., Srivastava K., Gill A.K. Post-translationally modified human lens crystallin fragments show aggregation in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2017;10:94–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Srivastava O.P., Srivastava K. Crosslinking of human lens 9 kDa gammaD-crystallin fragment in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Vis. 2003;9:644–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fan X., Zhou S., Monnier V.M. Evidence of highly conserved β-crystallin disulfidome that can be mimicked by in vitro oxidation in age-related human cataract and glutathione depleted mouse lens. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2015;14:3211–3223. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.050948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Serebryany E., Takata T., King J.A. Aggregation of Trp > Glu point mutants of human gamma-D crystallin provides a model for hereditary or UV-induced cataract. Protein Sci. 2016;25:1115–1128. doi: 10.1002/pro.2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harms M.J., Wilmarth P.A., Lampi K.J. Laser light-scattering evidence for an altered association of beta B1-crystallin deamidated in the connecting peptide. Protein Sci. 2004;13:678–686. doi: 10.1110/ps.03427504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilmarth P.A., Tanner S., David L.L. Age-related changes in human crystallins determined from comparative analysis of post-translational modifications in young and aged lens: does deamidation contribute to crystallin insolubility? J. Proteome Res. 2006;5:2554–2566. doi: 10.1021/pr050473a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Quintanar L., Domínguez-Calva J.A., King J.A. Copper and zinc ions specifically promote nonamyloid aggregation of the highly stable human γ-D crystallin. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016;11:263–272. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Domínguez-Calva J.A., Haase-Pettingell C., Quintanar L. A histidine switch for Zn-induced aggregation of γ-crystallins reveals a metal-bridging mechanism that is relevant to cataract disease. Biochemistry. 2018;57:4959–4962. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao L., Chen X.J., Zhang K. Lanosterol reverses protein aggregation in cataracts. Nature. 2015;523:607–611. doi: 10.1038/nature14650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shanmugam P.M., Barigali A., Minija C.K. Effect of lanosterol on human cataract nucleus. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2015;63:888–890. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.176040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kang H., Yang Z., Zhou R. Lanosterol disrupts aggregation of human γD-crystallin by binding to the hydrophobic dimerization interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:8479–8486. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b03065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shimeld S.M., Purkiss A.G., Lubsen N.H. Urochordate betagamma-crystallin and the evolutionary origin of the vertebrate eye lens. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1684–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lubsen N.H., Aarts H.J., Schoenmakers J.G. The evolution of lenticular proteins: the beta- and gamma-crystallin super gene family. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1988;51:47–76. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(88)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]