Abstract

The rate of hydrogen–deuterium exchange (HDX) in aqueous droplets of phenethylamine has been determined with submillisecond temporal resolution by mass spectrometry using nanoelectrospray ionization with a theta-capillary. The average speed of the microdroplets is measured using micro-particle image velocimetry. The droplet travel time is varied from 20 μs to 320 μs by changing the distance between the emitter and the heated inlet to the mass spectrometer and the voltage applied to the emitter source. The droplets were found to accelerate by ~30% during their observable travel time. Our droplet imaging shows that the theta-capillary produces two Taylor cone–jets (one per channel), causing mixing to take place from droplet fusion in the Taylor spray zone. Phenethylamine (ϕCH2CH2NH2) was chosen to study because it has only one functional group (−NH2) that undergoes rapid HDX. We model the HDX with a system of ordinary differential equations. The rate constant for the formation of −NH2D+ from −NH3+ is 3660±290 s−1, and the rate constant for the formation of −NHD2+ from −NH2D+ is 3330±270 s−1. The observed rates are about 3 times faster than what has been reported for rapidly exchangeable peptide side-chain groups in bulk measurements using stopped-flow kinetics and NMR spectroscopy. We also applied this technique to determine the HDX rates for a small ten-residue peptide, angiotensin I, in aqueous droplets, from which we found a 7-fold acceleration HDX in the droplet compared to that in bulk solution.

Graphical Abstract

Hydrogen–deuterium exchange (HDX) has been very useful for the study of the dynamics of protein folding and ligand–protein interactions with NMR and mass spectrometry (MS).1,2 Understanding how accessible amino acid residues in a protein are to HDX reveals how buried or surface-exposed they are to the surrounding aqueous solution. Typically, only the amide groups in the peptide backbone that slowly exchange hydrogens with D2O are considered for structural analysis with MS, because the exchange rate of labile hydrogens located in the side chains is about two orders of magnitude faster.1,3–7 Exposing an amino acid side chain with a primary amine or a hydroxyl group to D2O causes equilibrium to be reached usually within seconds; by contrast, the amides in the peptide back-bone may take several minutes to hours. Therefore, side-chain HDX is very difficult to observe with MS because the peptides are usually eluted with a liquid chromatography gradient with H2O in the mobile phase, causing rapid back-exchange. Being able to study the dynamics of HDX in side chains may provide useful complementary structural information. The extremely fast dynamics of peptide side chain HDX has limited studies to subsecond interactions with MS, in which peptides have been reacted with ND3 in the gas phase inside the ion transfer system of the MS.8–11 Un-fortunately, these reactions are far removed from bio-chemical liquid-phase conditions. We present here a means for determining the liquid-phase rates of HDX in primary amines and peptides with MS. The method is general and may have wide applicability.

We used nanoelectrospray ionization (nanoESI) with a theta-capillary to enable measurements in the liquid phase of rapid HDX in functional groups located in the side chains of peptides. Previously, the Derrick and Williams groups extensively used theta-capillaries for studies of rapid reactions with MS,12–16 where different analytes are loaded into each channel and then ejected through nanoESI17 by applying the same polarity of spray voltage to each channel. The technique can be considered an extension of reactive desorption electrospray ionization (DESI).18–20 In addition, experiments in which reactions take place through the fusion of microdroplets have been shown to occur at rates that are up to a million times faster than in bulk.19,21–26

Although there are similarities between the concepts of using theta-capillaries and DESI-spray sources for microdroplet reactions, two major differences are the absence of sheath gas in the nanoESI setup with theta-capillaries and their much smaller tip size. These differences make the resulting droplets much smaller and slower, effectively changing the mixing time of colliding droplets.27 Although measurements of droplet size and velocity have been made for DESI micro-droplet reactions, this has never been done for a nanoESI theta-capillary setup, leaving prior estimates of droplet reaction times for theta-capillaries mainly speculative.

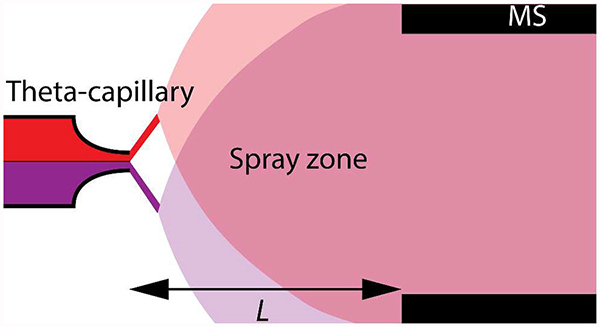

Here we found that when using a constant tip size, spray voltage, and backing pressure, the reaction can be modulated by simply moving the theta capillary back and forth within a range of 0.5–3 mm, as this will change the reaction time during which the reagents interact (during microdroplet collisions), before they enter the mass spectrometer for detection. We loaded the theta-capillary with 1 μM phenethylamine or 1 μM angiotensin I in one channel and D2O in the other channel to study HDX (Figs. 1 and 2).

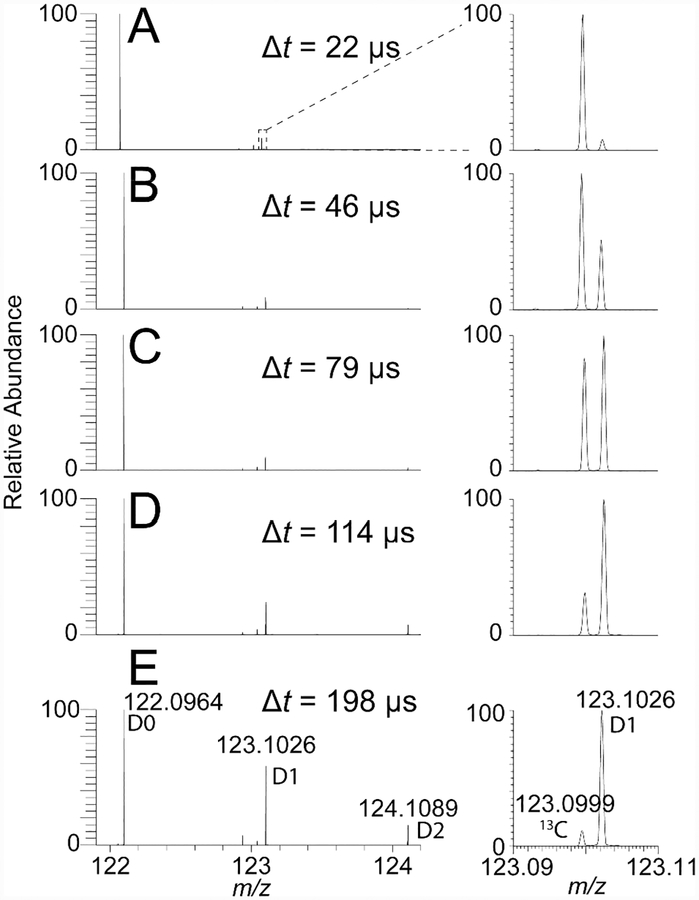

Figure 1.

Hydrogen–deuterium exchange observed in phenethylamine m/z 122.096 (D0), with nanoESI using a theta-capillary. The extent of deuteration (D1, m/z 123.103; D2, m/z 124.109) increases by moving the capillary further back from the inlet of the mass spectrometer. (A) Δt = 22 μs, TIC: 2.4 x 105; (B) Δt = 46 μs, TIC: 3.1 x 105; (C) Δt = 79 μs, TIC: 2.5 x 105; (D) Δt = 114 μs, TIC: 1.4 x 105; and (E) Δt = 198 μs, TIC: 6.4 x 104; where Δt is the average dwell time for droplets in air before entering the mass spectrometer, and TIC is the total ion current. The inset on the right (m/z 123.09–123.11) of each panel shows the relative intensities of the naturally occurring 13C isotope (left) and the D1 isotope (right) of a protonated phenethylamine ion.

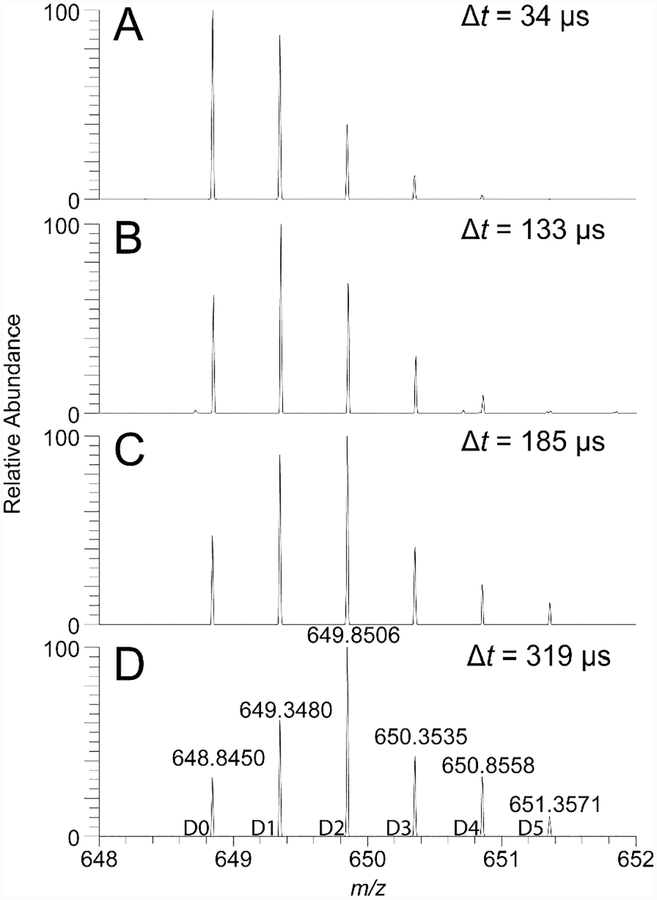

Figure 2.

Hydrogen–deuterium exchange observed in angiotensin I, m/z 648.85, with nanoESI using a theta-capillary. The extent of deuteration increases by pulling the capillary further back from the inlet of the mass spectrometer. (A) Δt = 34 μs, TIC: 2.6 x 106; (B) Δt = 133 μs, TIC: 8.4 x 104; (C) Δt = 185 μs, TIC: 8.0 x 103; and (D) Δt = 319 μs, TIC: 5.6 x 103; where Δt is the average dwell time for droplets in air before they enter the mass spec-trometer, and TIC is the total ion current.

Phenethylamine is a small aromatic compound (121.2 Da) with a single primary amine; hence, it has two rapidly exchangeable hydrogens (Fig. S1A). Angiotensin I is a peptide with 10 amino acid residues and a monoisotopic mass of 1295.7 Da (Fig. S1B). The peptide has 17 groups that have exchangeable hydrogens, out of which 4 are considered to be rapidly exchangeable (primary amines and hydroxyl groups). We monitored HDX of phenethylamine at [M+H]+ (Fig. 1) and angiotensin I at [M+2H]2+ (Fig. 2). The reaction time is determined by the average time it takes for droplets to mix and travel from the beginning of the mixing zone outside the theta-capillary tip to the MS inlet. We used choline and choline-d9 as internal standards in each capillary (Fig. S2) to monitor the effective mixing rate of analytes reaching the MS. The mixing ratio was found to be ~1:1 H2O:D2O. Moving the capillary be-yond a 3 mm distance should further increase the reaction time; however we found that at such a distance the signal intensity was too low for analyte detection. We measured the velocity field for microdroplets emitted from a theta-capillary, obtained by imaging the spray with micro-particle imaging velocimetry using two Nd:YAG lasers.28–30 The droplets were on average 4.3 μm in diameter and travelled at average speeds of 8–23 m·s−1 depending on the electric field between the capillary tip (2.00±0.18 μm) and the MS inlet (Table 1, Fig. S3–S6, SI Notes 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Electric field strength E, average droplet velocity u, and capillary flow rates Q during nanoESI as a function of distance d, and spray voltage ϕ, when 10 psi N2 backing pressure was applied.

| ϕ (kV) | d (mm) | E (V·cm−1) | u (m·s−1) | Q (μl·min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.92 | 10870 | 15.3±1.4 | 1.31±0.24 |

| 1.45 | 6900 | 13. 6±2.5 | 1.05±0.19 | |

| 1.69 | 5920 | 12.7±2.2 | 0.99±0.18 | |

| 2.58 | 3880 | 7.8±1.0 | 0.64±0.11 | |

| 1.5 | 0.65 | 23080 | 23. 3±3. 3 | 1.89±0.34 |

| 1.63 | 9200 | 15.2±2.9 | 1.16±0.21 | |

| 1.71 | 8770 | 16.0±3.9 | 1.14±0.21 | |

| 1.88 | 7980 | 13.6±3.3 | 0.96±0.17 | |

| 2.45 | 6120 | 12.8±2.0 | 1.02±0.18 |

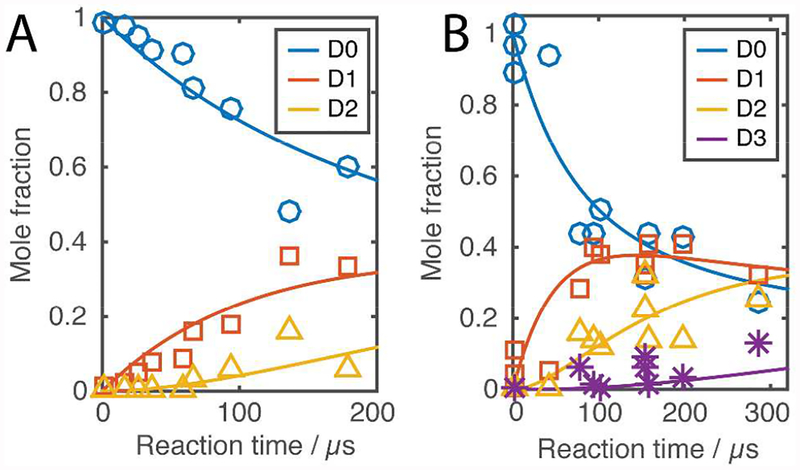

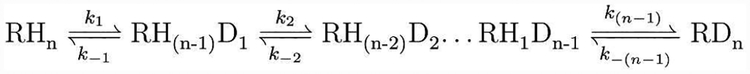

For phenethylamine, the high mass resolution of the instrument we used allowed us to independently monitor the abundance of the naturally occurring isotopes and the deuterated isotopes as a function of reaction time (Fig. 1 and 3A). A decay of the monoisotopic peak was observed for phenethylamine while the deuterated peaks were growing. The deuteration of a com pound with n exchangeable hydrogens can be described as a system of coupled reactions with forward and backward reaction rates ki and k-i (Scheme 1). We modeled the reaction as a system of ordinary differential equations (SI Note 3) and fitted the rate constants for the observed reactions (Table 2), which were 3660±290 s−1 for the formation of −NH2D+ from −NH3+ and 3330±270 s−1 for the formation of −NHD2+ from −NH2D+, a 3-fold higher rate than what has been observed for primary amines in stopped flow kinetic experiments performed in bulk.1,3–7 For angiotensin I, we observed subsequent shifting of the isotopic envelope to the right (Fig. 2). Spectral deconvolution of the data obtained for angiotensin I allowed us to calculate the molar fraction of each component. Figure 3B shows the relative abundance of several isotopes as a function of time. Just like phenethylamine, a decay of the monoisotopic peak was observed for angiotensin I while the deuterated peaks were growing. The first deuterated isotope peak was observed to reach a plateau and then regress, which is expected as HDX of the peptide progresses over time. Table 2 presents the rate constants. For comparison, the decay of the monoisotopic peak for phenethylamine is attributed solely to its primary amine group, but the decay of the monoisotopic peak in angiotensin I is a result of HDX at an ensemble of sites. However, because the exchange rate of the primary amine phenethylamine is ~3 times slower than the measured rate of angiotensin I, it is reasonable to consider that HDX in angiotensin I initially happens at hydroxyl groups in the side chain of the peptide. HDX at hydroxyl groups, for example in tyrosine, is 1.5–3 times faster compared to primary amines.1,3–7 If the decay rate of angiotensin I is attributed solely to the tyrosine group that has the fastest exchange rate of all side-chain groups, the lower limit of the rate we observed is 7-fold faster compared to the literature values obtained in bulk reactions, and the ratio between the exchange rate for phenethylamine and angiontensin I in microdroplets appear to be similar to the ratio in bulk.1,3–7

Figure 3.

Isotopic patterns resulting from HDX in (A) phenethylamine and (B) angiotensin I (after spectral deconvolution) provided the kinetic behavior of individual components. Labels indicate the monoisotopic peak D0, first deuterated peak D1, second deuterated peak D2, etc. The graphs show the solutions for the systems of ordinary differential equations based on the obtained forward and backward reaction rates. Increasing the distance between the capillary tip and the inlet of the mass spectrometer results in an increased reaction time. As a result, the monoisotopic compound decreases in intensity as HDX proceeds.

Scheme 1.

Coupled reactions of HDX in n states.

Table 2.

Forward and backward reaction rate constants for hydrogen–deuterium exchange of phenethylamine and angio-tensin I calculated for the experimental conditions in 50/50 H2O/D2O.

| Reaction rate (s−1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | k1 | k−1 | k2 | k−2 | k3 | k−3 |

| Phenethylamine | 3660±290 | 2590±210 | 3330±270 | 2350±190 | ||

| Angiotensin I | 9540±760 | 6750±540 | 6020±480 | 4250±340 | 1086±87 | 768±61 |

Previous reports suggested that the increased rate observed in microdroplet reactions is a result of evaporation and resulting concentration increase, which in turn would drive the reactions at higher rates.19,21 However, in the present study the initial droplet mixing yields a million-fold excess of D2O in relation to the analyte under study for HDX. We modeled the convective evaporation rate for droplets travelling in air and found that in our system the droplet size is at most de-creased by ~1.2% during its flight time (Fig. S8, SI Note 4).31 This corresponds to a 3.6% reduction of the initial volume. Thus, we can rule out evaporation effects on concentrations and reaction rates. Where does the shift in reaction rates come from? HDX can be acid, base, and/or water catalyzed.6,32 Therefore, we hypothesize that the observed changes of rates compared to bulk measurements arise from local pH shifts in the droplets on the surface,33,34 caused by a large number of positive charges deposited in the droplets through the ESI mechanism or through concentration redistribution of the positively charged analytes to the surface.22,35

In a nanoESI setup where theta capillaries are used, the reagents contained in the two channels will not interact until they are ejected from the tip of the theta capillary. However, no previous studies using a theta-capillary system for nanoESI have attempted to measure the velocity or size of the resulting droplets, such that the effective mixing time has remained unknown. We found two separate Taylor cone–jet regions that repel each other during nanoESI with theta-capillaries (Fig. S5, SI Note 1), by imaging the resulting spray at 500 ns intervals with ≤25 ns light pulses from Nd:YAG lasers, effectively “freezing” the drop-lets in each frame. The two channels at the tip orifice are separated by a 0.15 μm thick borosilicate wall (a good insulator). A small wetted interface between the two channels should exist; however, we estimate that mixing between the analytes in the Taylor cone–jet region is at least 105 times smaller than (Fig. S7, SI Note 2 inertial mixing between droplets colliding with one another in the spray region. The reaction is expected to be quenched upon entry in the heated capillary as previous studies suggest.23,24 Because charged analytes could leave the droplets with no charge left behind on the large droplet through Coulombic fission, our measurements of droplet time of flight should be considered as an upper limit of reaction time. Fission resulting in droplets that are one order of magnitude smaller than the parent droplets (~0.1 μm) are calculated to evaporate within 30 μs and could result in reaction times that are even shorter than what we estimate through the time of flight for the parent droplets. As such, we have here provided a lower limit of the acceleration of reaction rates in microdroplets.

Chemical reactions in microdroplets are interesting to study because the dispersion of a liquid into droplets shifts the regime from bulk to surface reactions, and the various techniques used are able to characterize reactions down to submillisecond timescales. Also, the apparent rates for many reactions are faster compared to the rates in bulk,21–24,26 emphasizing a strong shift of the dynamic behavior of reactions during the transition from bulk to the microscale environment. We suggest that this technique may prove useful for general inter-rogations of dynamic interactions between ligands and the side chains in a protein.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maria T. Dulay for kind assistance with SEM imaging. E.T.J. was supported by the Swedish Research Council, through award no. 2015-00406. Y.-H. L. was supported by the Program of Talent Development of Academia Sinica, Taiwan. This work has been supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under grant R01-MH112188.

Footnotes

The Supporting Information (PDF) describing materials and methods, Supporting Figures S1–S7, and Supporting Notes 1–4 are available free of charge on the ACS Publi cations website.

REFERENCES

- (1).Englander SW; Kallenbach NR Q. Rev. Biophys 1983, 16, 521–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Katta V; Chait BT Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 1991, 5, 214–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Takahashi T; Nakanishi M; Tsuboi M Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 1978, 51, 1988–1990. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Takahashi T; Nakanishi M; Tsuboi M Anal. Biochem 1981, 110, 242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Tuchsen E; Woodward C Biochemistry 1987, 26, 8073–8078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Liepinsh E; Otting G Magn. Reson. Med 1996, 35, 30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Henry GD; Sykes BD J. Biomol. NMR 1995, 6, 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Rand KD; Pringle SD; Murphy JP; Fadgen KE; Brown J; Engen JR Anal. Chem 2009, 81, 10019–10028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Rand KD; Pringle SD; Morris M; Brown JM Anal. Chem 2012, 84, 1931–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Mistarz UH; Brown JM; Haselmann KF; Rand KD Anal. Chem 2014, 86, 11868–11876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Geller O; Lifshitz CJ Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 2217–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Mark L; Gill M; Mahut M; Derrick P Eur. J. Mass Spectrom 2012, 18, 439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Mortensen DN; Williams ER Anal. Chem 2014, 86, 9315–9321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Mortensen DN; Williams ER Anal. Chem 2015, 87, 1281–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Mortensen DN; Williams ER J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 3453–3460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Radionova A; Greenwood DR; Willmott GR; Derrick PJ Mass Spectrom. Lett 2016, 7, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wilm M; Mann M Anal. Chem 1996, 68, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Song Y; Cooks RG J. Mass Spectrom 2007, 42, 1086–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Girod M; Moyano E; Campbell DI; Cooks RG Chem. Sci 2011, 2, 501–510. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Perry RH; Splendore M; Chien A; Davis NK; Zare RN Angew. Chem. Int. Edit 2011, 50, 250–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Bain RM; Pulliam CJ; Cooks RG Chem. Sci 2015, 6, 397–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Fallah Araghi A; Meguellati K; Baret J; El Harrak A; Mangeat T; Karplus M; Ladame S; Marques CM; Griffiths AD Phys. Rev. Lett 2014, 112, 028301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Müller T; Badu - Tawiah A; Cooks RG Angew. Chem. Int. Edit 2012, 51, 11832–11835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lee JK; Kim S; Nam HG; Zare RN Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2015, 112, 3898–3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Liu P; Zhang J; Ferguson CN; Chen H; Loo JA Anal. Chem 2013, 85, 11966–11972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Badu Tawiah AK; Campbell DI; Cooks RG J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2012, 23, 1461–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Carroll B; Hidrovo C Heat Transfer Eng 2013, 34, 120–130. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Meinhart CD; Wereley ST; Santiago JG J. Fluids Eng 2000, 122, 285–289. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Meinhart C; Wereley S; Gray M Meas. Sci. Technol 2000, 11, 809. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Wereley ST; Meinhart CD Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech 2010, 42, 557–576. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Holterman H Kinetics and evaporation of water drops in air 2003, 2003–12, IMAG, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Jensen PF; Rand KD Hydrogen Exchange: A Sensitive Analytical Window into Protein Conformation and Dynamics In Hydrogen Exchange Mass Spectrometry of Pro teins John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: 2016; pp 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Zhou S; Prebyl BS; Cook KD Anal. Chem 2002, 74, 4885–4888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Girod M; Dagany X; Antoine R; Dugourd P Int. J. Mass Spectrom 2011, 308, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Li Y; Yan X; Cooks RG Angew. Chem. Int. Edit 2016, 55, 3433–3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.