Abstract

Objective:

People with chronic insomnia tend to have cortical hyperarousal marked by excessive beta-/gamma-frequency brain activity during both wake and sleep. Currently, treatment options for managing hyperarousal are limited. Open-loop audiovisual stimulation (AVS) may be such a treatment. The purpose of this study was to provide a mechanistic foundation for future AVS research in sleep promotion by examining quantitative electroencephalogram (QEEG) responses to an AVS sleep-induction program.

Method:

Sixteen older adults with both chronic insomnia and osteoarthritis pain were randomly assigned to either active- or placebo-control AVS. Electroencephalogram (EEG) was collected during baseline (5 min, eyes closed/resting) and throughout 30 min of AVS.

Results:

Findings showed significantly elevated mean baseline gamma (35–45 Hz) power in both groups compared to an age- and gender-matched, noninsomnia normative database, supporting cortical hyperarousal. After 30 min of exposure to AVS, the active group showed significantly increased delta power compared to the placebo-control group, providing the first controlled evidence that active AVS induction increases delta QEEG activity in insomnia patients and that these changes are immediate. In the active group, brain locations that showed the most delta induction (Cz, Fp, O1, and O2) were associated with the sensory–thalamic pathway, consistent with the sensory stimulation provided by the active AVS program.

Conclusions:

Findings demonstrate that delta induction, which can promote sleep, is achievable using a 30-min open-loop AVS program. The potential for AVS treatment of insomnia in the general population remains to be demonstrated in well-designed clinical trials.

Keywords: audiovisual stimulation (AVS), delta induction, insomnia, hyperarousal, osteoarthritis pain

Osteoarthritis (OA) affects 50% of people aged 60 or older, translating to 130 million older adults worldwide (Lim & Lau, 2011). Approximately 80% of older adults with OA report significantly disturbed sleep, making OA-related insomnia the most common form of comorbid insomnia in aging populations (Abad, Sarinas, & Guilleminault, 2008; Foley, Ancoli-Israel, Britz, & Walsh, 2004; Sarzi-Puttini et al., 2005). While the relationship between insomnia and chronic pain such as OA pain can be reciprocal, findings from a recent systematic review of prospective and experimental studies suggest that sleep disturbance is a reliable predictor of new onset as well as the continuation of chronic pain (Finan, Goodin, & Smith, 2013). One study also found that short-term improvements in sleep predicted long-term improvements in insomnia symptoms, chronic pain, and fatigue among older adults with OA (Vitiello et al., 2013). In combination, these findings suggest that treating sleep might improve pain and associated outcomes including function and mood (Smith & Haythornthwaite, 2004).

Standard treatment options for insomnia are cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) and medication. CBT-I is the recommended first line of treatment. Treatment effects for CBT-I are comparable to or exceed those observed for medications (Qaseem, Kansagara, Forciea, Cooke, & Denberg, 2016), and it has been shown to be efficacious for persons with OA pain. Despite this well-demonstrated efficacy, credentialed CBT-I clinicians are not yet widely available in many health-care systems. Prescription medication has good short-term efficacy; yet benefits do not persist after treatment discontinuation, there are notable side effects and risks (e.g., dependence, rebound insomnia, falls, and cognitive impairment); and medication is not recommended for treatment of chronic insomnia (Glass, Lanctot, Herrmann, Sproule, & Busto, 2005).

Insomnia is characterized by difficulties initiating (latency) and/or maintaining sleep as well as early morning awakenings (EMA), with resulting daytime dysfunction complaints. Regardless of the insomnia subtype (sleep latency, maintenance, or EMA), researchers have hypothesized that cognitive and/or physiological hyperarousal is a key factor contributing to insomnia symptoms (Altena et al., 2017). In a recent review paper, Krone et al. (2017) described a top-down regulation model suggesting that arousal and sleep in humans can be modulated through changes in cortical activity induced by noninvasive brain-stimulation techniques such as cerebral thermal transfer, sensory stimulation, transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial current stimulation, sensory stimulation, and electromagnetic field and radio-frequency exposure. The top-down regulation conceptual framework and the early evidence provide new insight about the potential of noninvasive, nonpharmacological interventions for sleep promotion. Open-loop audiovisual stimulation (AVS), which operates on a concept similar to other brain-stimulation techniques, has the potential to induce delta brain waves for sleep promotion and could be a treatment alternative.

Human brain waves mimic the frequency of sensory stimuli that the brain receives. Adrian and Matthews (1934) first documented the observation of brain wave correspondences to photic stimulation, followed by Walter and Walter’s (1949) study reporting changes in both brain waves and subjective sensory perception. A study by Chatrian, Peterson, and Lazarte (1960) showed changes in brain-wave response to auditory stimulation, independent of visual input.

Since these early observations, clinicians and scientists have used a combination of audio and visual stimulation to regulate human brain waves for treatment of a variety of clinical conditions or cognitive difficulties, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, cognitive enhancement, stress management, and migraine headache (Huang & Charyton, 2008). Although the application of AVS has been tested in some clinical conditions, there is limited literature examining the effect of AVS on deep relaxation or sleep promotion. While the mechanism for AVS remains under debate, a noncontrolled study conducted by Teplan, Krakovska, and Stolc (2006b) with six healthy adult volunteers demonstrated direct cortical activity reaction to a wide-ranging 20-min AVS. Repetitive training (25 sessions of the same 20-min AVS) over a period of 2 months significantly reduced beta and gamma activity measured at 3 min after the stimulation, suggesting an adaptive self-regulation process for deep relaxation (Teplan, Krakovska, & Stolc, 2006a). The authors’ rationale for their AVS wide-ranging stimuli composition was that the program is more suitable for individuals new to AVS (Teplan, Krakovska, & Stolc, 2011).

In contrast to Teplan et al.’s wide-ranging AVS approach for producing a relaxation response, our team has used progressive downward brain activity stimuli training for theta/delta induction specific to our intention to impact sleep. Our conceptual framework is that AVS provides exogenous stimulation to entrain cortical activity to slower frequencies (delta, theta), facilitating a receptive condition for the induction of sleep. We conducted prior uncontrolled pilot studies examining the feasibility of a 30-min self-administered, descending-frequencies AVS regimen prior to bedtime (details of stimuli composition described under “Materials and Methods” section) for 1 month to improve sleep (Tang, Vitiello, Perlis, Mao, & Riegel, 2014; Tang, Vitiello, Perlis, & Riegel, 2015). While evidence from these early pilot studies supports the potential role of AVS in sleep promotion based on subjective reports of sleep improvement, the actual corresponding EEG changes in response to a descending AVS program have not been previously described.

The purpose of the current study was to provide a mechanistic foundation for future AVS research by examining the a priori hypothesis that a 30-min AVS delta-induction program can induce EEG delta brain-wave changes as measured by quantitative electroencephalogram (QEEG) in a randomized controlled study.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Recruitment

This study was a secondary analysis of baseline data from a recently completed pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) using AVS to enhance sleep in older adults with insomnia and moderate-to-severe OA pain. Participants were recruited from the University of Washington (UW) Medical Clinical Data Repository (CDR). The CDR listed 22,874 patients aged 60 years and older who had one or more visits associated with an OA diagnosis in the greater Seattle area between July 2012 and July 2015. Potential participants were sent an invitation e-mail describing the study. People who responded were screened over the phone to determine eligibility, and then a consent and baseline assessment session was scheduled at UW.

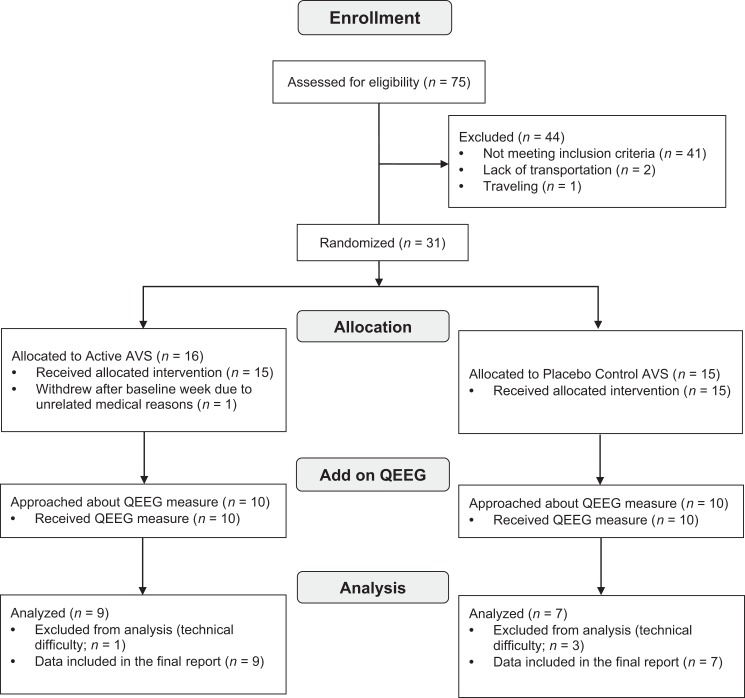

The QEEG measure was added midway during the parent RCT with the intention of examining the a priori hypothesis that a 30-min AVS delta-induction program could induce EEG changes associated with AVS stimulation. All participants enrolled after that midpoint were approached to participate in this substudy, and all agreed to the QEEG measure. This QEEG subsample included 16 older adults, aged 60 years or older, who enrolled in a study testing the sleep-promotion effects of a 30-min AVS program compared to placebo-control AVS used at bedtime for 2 weeks (clinicaltrial.gov # NCT03441191; Figure 1). The UW Human Subjects Division approved the study.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram. AVS = audiovisual stimulation; QEEG = quantitative electroencephalogram.

The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: 60 years of age or older, having difficulty sleeping over the past 3 months (Insomnia Severity Index [ISI] score ≥ 8), and having OA pain (Brief Pain Inventory worst pain score ≥ 4). Exclusion criteria were as follows: working night shift, previously diagnosed with a primary sleep disorder (sleep apnea or restless legs syndrome), known seizure disorder, history of traumatic brain injury, photosensitivity, severe sensory impairment, use of psychoactive agent, cognitive impairment, dementia diagnosis or other significant chronic illness beyond OA that would impact sleep, and/or a severe psychiatric disorder including a history of or current diagnosis of psychosis.

Measures

Demographics

Participant age, gender, ethnic group, medication information, use of supplements, and handedness were collected at baseline.

Sleep

The ISI and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) were used to assess subjective sleep quality and disturbance. The ISI is a validated 7-item questionnaire that measures global insomnia severity; each item has a score range of 0–4, and total scores range from 0 to 28, with higher scores indicating more severe insomnia (Bastien, Vallieres, & Morin, 2001; Morin, Belleville, Belanger, & Ivers, 2011). The PSQI is a well-established tool that rates self-reported sleep quality and disturbances over the past month (Buysse et al., 2008). The instrument comprises 19 items that measure seven components of sleep: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medications, and daytime dysfunction. Each domain is weighted equally on a 0–3 scale, contributing to a total PSQI score that ranges between 0 and 21, with higher scores indicating worse sleep quality.

Pain

Pain severity was measured using the Brief Pain Inventory–Short Form (BPI-sf), a validated, widely used questionnaire for assessing pain intensity and interference with activities (Cleeland & Ryan, 1994). The BPI-sf rates pain intensity (4 items) and interference (7 items); each item has a score range of 0–10; higher scores indicate greater pain and interference. The scale is validated for use in clinical trials with OA pain patients (Mendoza, Mayne, Rublee, & Cleeland, 2006).

Depression

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) was used to assess depression at baseline. The PHQ-9 is a reliable, valid, dimensional measure of depression symptom severity. A 4-point scale rates frequency of the occurrence of nine depressive symptoms. Moderate depression is indicated by a PHQ score ≥ 10. In the present study, when we use the term depression, we are referring, not to a clinical diagnosis, but rather to the PHQ-9’s measure of depressive symptomology.

QEEG

Cortical activity was evaluated using a 19-channel QEEG system (Discovery 24E, BrainMaster Technologies, https://www.brainmaster.com/product/discovery-24e/) with a standard 22-sensor electrode cap. Investigators have used the Discovery 24E QEEG system previously for QEEG measurement in clinical research (Bonnstetter, Hebets, & Wighton, 2015; Mumtaz, Xia, Mohd Yasin, Azhar Ali, & Malik, 2017; Wigton & Krigbaum, 2015). A bioengineer in the health sciences at the university who specialized in scientific instruments calibrated the device routinely. A standard bio-calibration procedure was conducted for each participant at the beginning of the QEEG collection. The purpose of the bio-calibration is to detect potential issues such as loose electrodes; dislodged sensors; 60-Hz interference; excessive electrocardiography artifact with the EEG, electrooculography, or electromyography channels; application breakdown; or equipment malfunction.

The collected raw EEG data were uploaded to an US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved QEEG analysis portal (qEEG-Pro), where the data were cleaned of artifacts using a standardized artifact rejection algorithm (SARA). SARA evaluates four different EEG artifact categories: eye blinks, horizontal eye movements, low-frequency artifacts (e.g., head movement), and high-frequency artifacts (e.g., muscle tension). As part of the cleaning procedure, an epileptiform episode detection algorithm detected very high-powered, low-frequency artifacts that can be elicited by epileptiform activity. When the cleaning procedure was complete, a report was generated showing the raw EEG in which the detected artifacts were marked in the time series.

The cleaned EEG was then processed and compared with the relevant age bin of the qEEG-Pro database (N = 1,482). Final reports consisted of the following analyses: fast Fourier transform (FFT) absolute power, FFT-relative power, phase coherence, alpha peak detection, amplitude asymmetry, phase lag, co-modulation (cross-frequency power correlations), burst metrics, extreme z-score development (age-simulation analyses), power fluctuation analyses, and percentage deviant activity. The qEEG-Pro database outputs reports in the following frequency bins: delta (1–3 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (12–35 Hz), and gamma (35–45 Hz). In the present study, the absolute power z-score over the Cz location was used as the primary outcome measure to evaluate QEEG response to AVS because Cz is used conventionally in the neurofeedback literature to monitor responses to intervention.

AVS Programs

A commercially available AVS device (MindPlace Procyon) was used to deliver the AVS programs in the present study. The AVS device is a pocket-sized player with standard headphones and LED goggles (https://mindplace.com/collections/light-and-sound/products/mindplace-procyon-avs-system-light-and-sound-meditation-mind-machine). Through investigator-initiated efforts, MindPlace agreed to modify the standard light- and sound-stimulation program to create active- and placebo-control AVS programs for the research study. We used similar AVS devices in our prior pilot studies (Tang et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2015).

The active AVS program consisted of a 30-min pulsing light (red and green spectrum [goggles]) and pulsing binaural sounds (headphones) that gradually descended from alpha (10 Hz) to delta (2 Hz) frequencies to entrain the EEG to a deep relaxation and sleep state. The protocol consisted of stimulation from 10 to 6 Hz during first 3 min, then 6–3 Hz at 4–28 min, and 3–2 Hz at 29–30 min.

The placebo-control program consisted of 30 min of constant dim light (goggles) that slowly changed in color and a steady monotone (headphones) at an ultralow frequency (below 1 Hz, outside of the entrainment range). The protocol consisted of stimulation from 1 to 0.4 Hz during first 3 min, then 0.4–0.2 Hz at 4–6 min, and 0.2 Hz at 7–30 min. The intent of this placebo AVS program was to simulate a light- and sound-stimulation experience but with minimal impact on EEG activity.

Procedure

Participants who met study eligibility criteria were enrolled and randomly assigned to either the active AVS group or placebo control using a computer-generated random list. Once enrolled, participants met with a researcher for an initial individual in-person assessment and training session. All meetings were scheduled in the afternoons between 1 and 3 p.m. to take advantage of the dead zone in the light and activity circadian-phase response curves. During this meeting, the researcher collected demographic, sleep, pain, and depression measures. No participants had prior experience with AVS. Participants were then introduced to the AVS protocol and participated in a 30-min session in a laboratory where ambient lighting, room temperature (65° F), and humidity (30%) were controlled. Participants were seated in a recliner chair in a resting position. Brain-wave data were collected using a standard 19-channel EEG cap, with the 10–20 international measure, and standard electroconductance gel was applied to specific sites of the scalp, allowing a clean measure of participant EEG. Sensor impedance was kept under 50 kΩ for all 19 channels. Common reference for the 19 channels was the participant’s right ear, with the ground lead on the left ear. The collected EEG data included baseline (5-min eyes closed and resting), and the 30-min AVS training (active or placebo control). EEG was not an outcome measure in the trial; it was collected during the practice AVS section at baseline to examine the delta-induction mechanism.

Statistical Analyses

We screened the raw data of the self-report measures for accuracy, missing values, outliers, and distributional properties and cleaned the EEG raw data through the qEEG-Pro online portal prior to analysis. We described the sample with descriptive statistics for demographic and baseline variables. We compared baseline brain waves to a norm database matched for age, gender, handedness, and mental state (eyes closed, resting). A z-score of ≥1 is considered a significant difference. Descriptive analysis was used to describe baseline demographics, insomnia, pain, and depression data and one-way analysis of variance to assess group differences in the QEEG changes before and after the initial AVS induction at baseline. Repeated-measures analysis of covariance was used to compare QEEG during the resting state versus the last 10 min of AVS exposure between active- and placebo-control groups. Standardized low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA; Pascual-Marqui, 2002) was used to detect the approximate locations where the brain-wave change occurred in response to AVS. We conducted all analyses using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and set the level of statistical significance at p < .05.

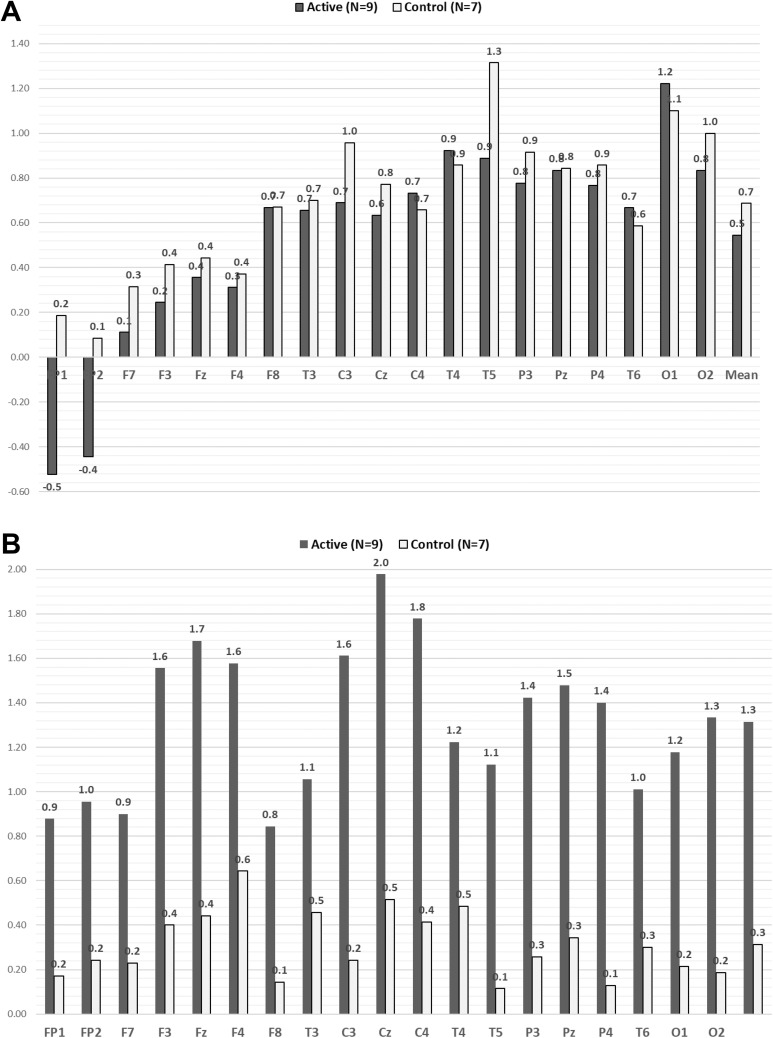

Results

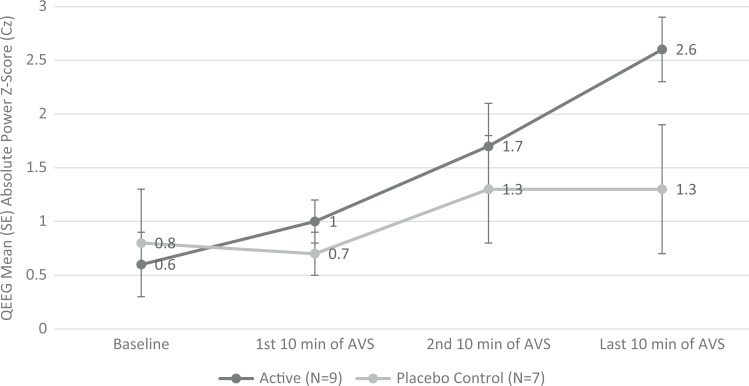

The study was conducted in Seattle, WA. The parent study ran from September to September of the following year. The average group enrollment was evenly distributed across the 12 months. All participants completed the study within 2–3 weeks, as required. A total of 16 older adults participated in the present QEEG substudy (active group: n = 9, mean age 67.2 ± 5.0 years; placebo-control group: n = 7, mean age 69.6 ± 4.4 years). All participants had clinical insomnia (ISI scores indicated subthreshold to severe), pain (BPI), and depression (PHQ-9 indicated mild-to-moderate symptom severity). There were no group differences on baseline covariates (Table 1). At baseline, the high-beta (21–34 Hz) and gamma (35–45 Hz) absolute power z-scores across 19 channels for all 16 participants (high-beta extreme z-score = 3.1 ± 1.7, mean dominant high-beta = 31 ± 4.6 Hz; gamma extreme z-score = 4.1 ± 1.9, mean dominant gamma = 38.8 ± 4.2) were higher than the age-, gender-, and handedness-matched norm database (see Figure 2A; Keizer & Mulder, 2017). Table 2 shows QEEG mean absolute power z-scores over Cz at baseline and in 10-min segments across the 30-min AVS induction. There were no group differences in baseline brain waves across all bandwidths. After the 30-min AVS, delta-induction mean average at the central Cz site differed significantly between groups (p = .003), but there were no group differences in the other bandwidths (theta, alpha, beta, gamma). We also observed significant group differences in changes in delta from baseline across all 19 channels (p = .02; see Figure 2B). In addition, within-group analyses showed significant delta induction at Cz for the AVS active group (p < .001) but not in the control placebo group (ns). Figure 3 shows the changes in Cz delta by Group × Time interaction. While we observed significant changes across all 19 channels in the active AVS group, we chose Cz as the primary reporting site due to its central location among the sites.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics and Sleep, Pain, and Depression Measures.

| Characteristic or Measure | Active (n = 9) | Placebo Control (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 67.2 ± 5.0 | 69.6 ± 4.4 |

| Sex, female (n [%]) | 9 (100) | 6 (85.7) |

| Race, White (n [%]) | 9 (100) | 6 (85.7) |

| ISIa | 18.4 ± 3.3 | 14.9 ± 3.0 |

| PSQIb | 11.3 ± 3.6 | 10.1 ± 2.2 |

| BPI, severityc | 4.4 ± 1.6 | 3.9 ± 2.0 |

| BPI, interferencec | 4.5 ± 2.5 | 4.2 ± 2.3 |

| PHQ-9d | 12.1 ± 6.3 | 7.1 ± 5.9 |

Note. Values are provided as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; ISI = Insomnia Severity Index; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

aISI: 0–7 no clinically significant insomnia, 8–14 subthreshold insomnia; 15–21 moderate severity clinical insomnia, and 22–28 severe clinical insomnia. bPSQI: <5 associated with good sleep quality and >5 associated with poor sleep quality. cBPI: 0 no pain/does not interfere and 10 pain as bad as you can imagine/completely interfere. dPHQ-9: 0–4 none to minimal depressive symptoms, 5–9 mild, 10–14 moderate, 15–19 moderately severe, and 20–27 severe depressive symptoms.

Figure 2.

Delta brain waves across 19 channels at baseline and during the last 10 min of the active or placebo AVS program. (A) Delta (z-score) at baseline (10 min, eyes closed, resting). (B) Delta (z-score) at last 10 min of the 30-min AVS intervention. AVS = audiovisual stimulation.

Table 2.

QEEG Mean (SD) Absolute Power Z-Score (10–20 System, Cz) Before and During 30 Min of the Assigned AVS Induction.

| Timing of the AVS Induction | Baseline | First 10 Min of AVS | Second 10 Min of AVS | Last 10 Min of AVS | Between-Group Baseline—Last 10 Min Change-Score Comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QEEG Frequency Bin | Active (n = 9) | Placebo Control (n = 7) | Active (n = 9) | Placebo Control (n = 7) | Active (n = 9) | Placebo Control (n = 7) | Active (n = 9) | Placebo Control (n = 7) | p | Cohen’s d (Effect Size, r) |

| Delta (1–3 Hz) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.8 (1.2) | 1.0 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.6) | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.5) | 2.6 (0.8) | 1.3 (1.5) | .003 | 4.47 (.91) |

| Theta (4–8 Hz) | 1.5 (1.3) | 1.8 (1.3) | 1.5 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.3) | 2.4 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.3) | .121 | 5.50 (.94) |

| Alpha (8–12 Hz) | 0.3 (1.2) | 1.3 (1.0) | 0.2 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.3) | 0.4 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.3) | 0.5 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.1) | .314 | 2.8 (.81) |

| Beta (12–35 Hz) | 0.6 (1.9) | 1.3 (1.0) | 0.7 (1.7) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.0 (1.4) | 1.0 (1.1) | 1.0 (1.2) | 1.0 (0.8) | .129 | 2.37 (.76) |

| Gamma (35–45 Hz) | 1.0 (1.1) | 1.0 (0.6) | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.9 (0.5) | 0.8 (1.2) | 0.7 (1.3) | 0.7 (1.2) | 0.7 (0.8) | .980 | 0.85 (.39) |

Note. AVS = audiovisual stimulation; QEEG = quantitative electroencephalogram.

Figure 3.

Change in mean (SE) Cz delta frequency QEEG mean absolute power z-score by group from baseline to end of 30-min AVS sleep-induction or placebo program. AVS = audiovisual stimulation; QEEG = quantitative electroencephalogram.

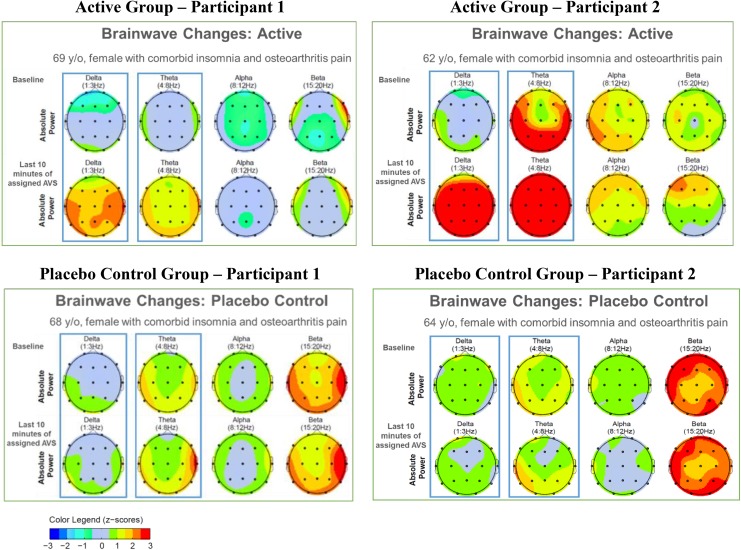

Figure 4 provides an illustration of QEEG topographs of four participants (two active, two placebo control) at baseline and during the last 10 min of the initial AVS training session. Warmer colors (yellow, orange, red) indicate more QEEG activity. At baseline, higher frequencies (beta and gamma) were predominant in three of the four participants. During the last 10 min of the active AVS, gamma decreased and there was more relative power in slower wave frequencies (delta and theta). In contrast, we observed minimal change from the baseline state in the participants who received placebo-control AVS.

Figure 4.

QEEG absolute power z-scores during baseline and last 10 min of either AVS sleep-induction or placebo program for representative active- and placebo-control participants. Boxes emphasize (1) predominance of higher frequencies at baseline and (2) the AVS-generated changes in delta and theta for each participant. AVS = audiovisual stimulation; QEEG = quantitative electroencephalogram.

Of the 19 channels (measured sites), the brain locations that showed the most delta induction in the active group compared to the placebo-control group were central (Cz; p = .003), frontal–parietal (Fp; p = .02), occipital left (O1; p = .03), and occipital right (O2; p = .003). Figure 5 shows the sLORETA brain electromagnetic tomograph at 2 Hz (delta) of the two participants from the active AVS group shown in Figure 4 at baseline and during the last 10 min of the active AVS induction. We observed increased cortical activities in the central, frontal–parietal, and occipital locations during the last 10 min of the of the active AVS induction compared to baseline.

Figure 5.

Brain regions responding to active AVS sleep-induction program via standardized low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography at 2 Hz (delta). AVS = audiovisual stimulation. aSame active AVS subjects as illustrated in Figure 4.

Discussion

Our findings in the present study provide evidence for a physiological mechanism underlying AVS delta induction, supporting the self-reported sleep improvements in our pilot studies where active AVS was used for several weeks at bedtime (Tang et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2015). After 30 min of the first exposure to the AVS program, the active treatment group showed significantly increased delta power compared to the placebo control. This finding provides the first controlled evidence in patients with insomnia that active AVS induction increases delta/theta EEG activity relative to placebo control and that these EEG changes are immediate. In the active AVS group, brain locations that showed the most delta induction were associated with the sensory–thalamic pathway, consistent with the sensory stimulation provided by the active AVS program.

We also observed significantly elevated mean gamma (35–45 Hz) power in both insomnia groups compared to an age- and gender-matched, noninsomnia normative database, indicating cortical arousal. This observation of excessive gamma, at a resting state with eyes closed, supports current hypotheses linking cortical hyperarousal to insomnia (Bonnet & Arand, 2010; Riemann et al., 2010).

The present study has some limitations. The sample size was small. The study design of EEG monitoring only at baseline and throughout 30 min of the initial AVS program does not allow for evaluation of the sustainability of delta-induction or self-reported sleep quality following repeated bedtime use of AVS. However, the study also has several strengths. To our knowledge, this study presents baseline QEEG data from the first RCT to compare active AVS versus placebo control in promoting delta induction to enhance sleep promotion. Not only does the study demonstrate immediate EEG changes in response to the progressive light- and sound-delta induction for the active group, but it shows the feasibility and acceptability of a novel placebo comparison condition. All QEEG data were collected during the afternoon between 1 and 3 p.m., a time during which deep relaxation was achievable, but the timing also presents an adequate challenge for delta induction when the sleep drive was not at its strongest (as compared to bedtime). Specifically, this timing fell during the dead zone in the light and activity circadian-phase response curves.

Our findings demonstrate that delta induction for sleep promotion is achievable using a 30-min open-loop AVS program. AVS is an inexpensive, easy-to-use nonpharmacological self-care intervention that could easily be adapted for home use in the community. AVS may have considerable potential for treatment of insomnia in the general population but only after rigorous testing in well-designed clinical trials.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Hsin-Yi (Jean) Tang contributed to conception, design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafted the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Susan M. McCurry contributed to conception, design, analysis, and interpretation; drafted the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Barbara Riegel contributed to conception, design, and interpretation; drafted the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Kenneth C. Pike contributed to conception, design, analysis, and interpretation; drafted the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Michael V. Vitiello contributed to conception, design, analysis, and interpretation; drafted the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by School of Nursing University of Washington, Center for Research on the Management of Sleep Disturbances funded by National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) National Institute of Health (NIH). (NINR 5-P30-NR011400).

References

- Abad V. C., Sarinas P. S., Guilleminault C. (2008). Sleep and rheumatologic disorders. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 12, 211–228. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2007.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrian E., Matthews B. (1934). The Berger rhythm: Potential changes from the occipital lobes of man. Brain, 57, 355–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altena E., Chen I. Y., Daviaux Y., Ivers H., Philip P., Morin C. M. (2017). How hyperarousal and sleep reactivity are represented in different adult age groups: Results from a large cohort study on insomnia. Brain Sciences, 7, 41 doi:10.3390/brainsci7040041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien C. H., Vallieres A., Morin C. M. (2001). Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Medicine, 2, 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet M. H., Arand D. L. (2010). Hyperarousal and insomnia: State of the science. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 14, 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnstetter R. J., Hebets D., Wighton N. L. (2015). Frontal gamma asymmetry in response to soft skills stimuli: A pilot study. Neuroregulation, 2, 70–85. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse D. J., Hall M. L., Strollo P. J., Kamarck T. W., Owens J., Lee L.…Matthews K. A. (2008). Relationships between the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and clinical/polysomnographic measures in a community sample. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 4, 563–571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatrian E. G., Peterson M. C., Lazarte J. A. (1960). Responses to clicks from the human brain: Some depth electrograph observation. Electroencephalography & Clinical Neurophysiology, 12, 479–489. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(60)90024-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland C. S., Ryan K. M. (1994). Pain assessment: Global use of the brief pain inventory. Annals, Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 23, 129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan P. H., Goodin B. R., Smith M. T. (2013). The association of sleep and pain: An update and a path forward. Journal of Pain, 14, 1539–1552. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2013.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley D., Ancoli-Israel S., Britz P., Walsh J. (2004). Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: Results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56, 497–502. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass J., Lanctot K. L., Herrmann N., Sproule B. A., Busto U. E. (2005). Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: Meta-analysis of risks and benefits. British Medical Journal, 331, 1169 doi:10.1136/bmj.38623.768588.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T. L., Charyton C. (2008). A comprehensive review of the psychological effects of brainwave entrainment. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 14, 38–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keizer A., Mulder D. (2017). qEEGPro database. Retrieved from http://qeegpro.eegprofessionals.nl/database/

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R. L., Williams J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone L., Frase L., Piosczyk H., Selhausen P., Zittel S., Jahn F.…Nissen C. (2017). Top-down control of arousal and sleep: Fundamentals and clinical implications. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 31, 17–24. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2015.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K., Lau C. S. (2011). Perception is everything: OA is exciting. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases, 14, 111–112. doi:10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01614.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza T., Mayne T., Rublee D., Cleeland C. (2006). Reliability and validity of a modified Brief Pain Inventory short form in patients with osteoarthritis. European Journal of Pain, 10, 353–361. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin C. M., Belleville G., Belanger L., Ivers H. (2011). The Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep, 34, 601–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumtaz W., Xia L., Mohd Yasin M. A., Azhar Ali S. S., Malik A. S. (2017). A wavelet-based technique to predict treatment outcome for major depressive disorder. PLoS One, 12, e0171409 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Marqui R. D. (2002). Standardized low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA): Technical details. Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology, 24, 5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qaseem A., Kansagara D., Forciea M. A., Cooke M., Denberg T. D. (2016). Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165, 125–133. doi:10.7326/M15-2175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann D., Spiegelhalder K., Feige B., Voderholzer U., Berger M., Perlis M., Nissen C. (2010). The hyperarousal model of insomnia: A review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 14, 19–31. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarzi-Puttini P., Cimmino M. A., Scarpa R., Caporali R., Parazzini F., Zaninelli A.…Canesi B. (2005). Osteoarthritis: An overview of the disease and its treatment strategies. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 35, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. T., Haythornthwaite J. A. (2004). How do sleep disturbance and chronic pain inter-relate? Insights from the longitudinal and cognitive-behavioral clinical trials literature. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 8, 119–132. doi:10.1016/s1087-0792(03)00044-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H. Y., Vitiello M. V., Perlis M., Mao J. J., Riegel B. (2014). A pilot study of audio-visual stimulation as a self-care treatment for insomnia in adults with insomnia and chronic pain. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 39, 219–225. doi:10.1007/s10484-014-9263-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H. Y., Vitiello M. V., Perlis M., Riegel B. (2015). Open-loop neurofeedback audiovisual stimulation: A pilot study of its potential for sleep induction in older adults. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 40, 183–188. doi:10.1007/s10484-015-9285-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplan M., Krakovska A., Stolc S. (2006. a). EEG responses to long-term audio-visual stimulation. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 59, 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplan M., Krakovska A., Stolc S. (2006. b). Short-term effects of audio-visual stimulation on EEG. Measurement Science Review, 6, 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Teplan M., Krakovska A., Stolc S. (2011). Direct effects of audio-visual stimulation on EEG. Computer Methods & Programs in Biomedicine, 102, 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello M. V., McCurry S. M., Shortreed S. M., Balderson B. H., Baker L. D., Keefe F. J.…Von Korff M. (2013). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for comorbid insomnia and osteoarthritis pain in primary care: The lifestyles randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61, 947–956. doi:10.1111/jgs.12275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter V. J., Walter W. G. (1949). The central effects of rhythmic sensory stimulation. Electroencephalography & Clinical Neurophysiology, 1, 57–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigton N. L., Krigbaum G. (2015). Attention, executive function, behavior, and electrocortical function, significantly improved with 19-channel Z-score neurofeedback in a clinical setting: A pilot study. Journal of Attention Disorders. doi:10.1177/1087054715577135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]