Abstract

Rationale: Cor pulmonale (right ventricular [RV] dilation) and cor pulmonale parvus (RV shrinkage) are both described in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The identification of emphysema as a shared risk factor suggests that additional disease characterization is needed to understand these widely divergent cardiac processes.

Objectives: To explore the relationship between computed tomography measures of emphysema and distal pulmonary arterial morphology with RV volume, and their association with exercise capacity and mortality in ever-smokers with COPD enrolled in the COPDGene Study.

Methods: Epicardial (myocardium and chamber) RV volume (RVEV), distal pulmonary arterial blood vessel volume (arterial BV5: vessels <5 mm2 in cross-section), and objective measures of emphysema were extracted from 3,506 COPDGene computed tomography scans. Multivariable linear and Cox regression models and the log-rank test were used to explore the association between emphysema, arterial BV5, and RVEV with exercise capacity (6-min-walk distance) and all-cause mortality.

Measurements and Main Results: The RVEV was approximately 10% smaller in Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage 4 versus stage 1 COPD (P < 0.0001). In multivariable modeling, a 10-ml decrease in arterial BV5 (pruning) was associated with a 1-ml increase in RVEV. For a given amount of emphysema, relative preservation of the arterial BV5 was associated with a smaller RVEV. An increased RVEV was associated with reduced 6-minute-walk distance and in those with arterial pruning an increased mortality.

Conclusions: Pulmonary arterial pruning is associated with clinically significant increases in RV volume in smokers with COPD and is related to exercise capacity and mortality in COPD.

Clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 00608764).

Keywords: COPD, right ventricle, vascular pruning, computed tomography

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Expiratory airflow obstruction and emphysema are shared risk factors for cor pulmonale and cor pulmonale parvus in smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Using computed tomography with deep learning processing approaches, we describe that loss of distal arterial vasculature is associated with pathologic right ventricular enlargement in those with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In those with arterial pruning, right ventricular enlargement is associated with an increased risk of death.

Cardiac dysfunction frequently occurs in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and is caused by a combination of direct injury by chronic tobacco smoke exposure and emphysematous destruction of the lung parenchyma accompanied by hyperinflation and pulmonary vascular remodeling (1–7). One manifestation of these processes is right ventricular (RV) enlargement and dysfunction, which is classically referred to as cor pulmonale (8, 9). This is a significant cause of disability and death in patients with COPD (10) but not all patients with COPD develop this condition. Several investigations have demonstrated that emphysema is also associated with decreased RV filling and reduced end-diastolic chamber size (cor pulmonale parvus) (7, 11, 12). The potential for either to exist in patients with COPD and the identification of emphysema as a potential risk factor for both suggests that additional disease characterization is needed to understand the mechanisms for these widely divergent cardiac processes.

We have developed image analysis algorithms that can objectively assess pulmonary arterial and venous vascular morphology in computed tomographic (CT) images of the chest. The vascular features extracted from this process include volumetric assessment of the distal intraparenchymal pulmonary vessels. We have previously demonstrated that objective measurements of these features are associated with clinical and physiologic manifestations of pulmonary vascular disease in multiple conditions including COPD and pulmonary arterial hypertension (13–17). We hypothesized that a direct assessment of pulmonary vascular morphology on CT may help explain the variable association between emphysema with RV enlargement. More specifically, we believed that subjects with emphysema with relatively preserved distal arterial vasculature would have a lower risk of cor pulmonale than those with similar amounts of emphysema but more extensive vascular pruning. In addition, once we defined this association, we sought to examine the clinical relevance of the interrelationship between RV enlargement and loss of the distal arterial vasculature with exercise capacity (6-min-walk distance [6MWD]) and survival in participants with COPD enrolled in the COPDGene Study.

Methods

Study Design

We tested these hypotheses in the COPDGene study, which is a longitudinal observational investigation that has been previously described in detail (18). Participant characterization in COPDGene included volumetric inspiratory and expiratory CT scans of the chest, questionnaires, and forced spirometry. Participants with previously diagnosed chronic lung diseases other than asthma, emphysema, or COPD were excluded.

CT Measurements

Volumetric CT scans of the chest were performed at both maximal inflation and relaxed exhalation. Lung volumes measured from CT at maximal inflation were expressed as a percent of predicted based on sex and race (TLCCT%) (18). Baseline (Round 1) images were acquired with the following CT protocol: for General Electric LightSpeed-16, General Electric VCT-64, Siemens Sensation-16 and -64, and Philips 40- and 60-slice scanners with 120-kVp, 200-mAs, and 0.5-second rotation time. Images were reconstructed using a standard algorithm at 0.625-mm slice thickness and 0.625-mm intervals for General Electric scanners; using a B31f algorithm at 0.625-mm (Sensation-16) or 0.75-mm slice thickness and 0.5-mm intervals for Siemens scanners; and using a B algorithm at 0.9-mm slice thickness and 0.45-mm intervals for Philips scanners (18).

Objective characterization of emphysema-like tissue was performed using a local histogram-based technique (19–24). The result was reported as the percent of emphysematous lung tissue for each participant herein referred to as percent emphysema. Morphologic assessments of the distal pulmonary vasculature were performed as described previously (13, 14, 15, 25) and the arterial and venous vascular components were separated using a deep learning approach (26). Arterial and venous volumes for vessels less than 5 mm2 in cross-section (arterial BV5 and venous BV5) were calculated for each participant. Finally, cardiac segmentation was performed using an atlas-based approach, a technique previously validated against cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (27, 28). RV and left ventricular (LV) epicardial volume (RVEV and LVEV) included both the wall and chamber volume. The epicardial surface rendering of the heart was visually inspected for quality control for each participant. Vascular and ventricular volumes were expressed in milliliters.

Lung Function, 6MWD, and Mortality

Spirometric measures of lung function including FEV1, FVC, and their ratio (FEV1/FVC) were performed using the Easy-One spirometer (ndd Medical Technologies Inc.). Testing was performed before and after the administration of a short-acting inhaled bronchodilating medication (albuterol) per American Thoracic Society recommendations and results were expressed as a percent of predicted values (i.e., FEV1%) (29, 30). Smokers with no evidence of spirometric obstruction (FEV1/FVC > 0.7 after the administration of a short-acting inhaled bronchodilator) were excluded from these analyses. The remaining COPDGene participants were classified into the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stages (1–4) of disease severity (31). Measures of 6MWD were expressed in feet. Mortality was determined as described previously using data from the National Death Index and from the COPDGene long-term follow-up program (32).

Statistics

Data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges for continuous covariates and percentages for categorical variables. Comparisons of RV morphology across sex- and race-stratified GOLD groups were performed using the Jonckheere-Terpstra test, which is a rank-based nonparametric test for ordered differences among classes (33). Multivariable linear regression models using continuous measures of the arterial BV5 and the analysis of covariance using categorical measures of the arterial BV5 (tertiles) were used to assess the relationship between CT measures of emphysema and arterial vascular morphology with the RVEV. Multivariable linear regression, multivariable Cox regression, and the log-rank test were used to assess the association between RV volume and the 6MWD and mortality.

Regression models were adjusted for age at subject enrollment (yr), sex, race, height (cm), FEV1%, smoking status (at the time of enrollment), TLCCT%, pack-years tobacco history, LVEV, venous BV5, and percent emphysema unless otherwise specified. All covariates were assessed using the Schoenfeld residuals method and none were found to violate the proportional hazards assumption (34). For the mortality analyses, effect estimates are given for those in the top quartile of RV volume compared with those in the bottom three quartiles. These models were stratified by vascular pruning (defined as an arterial BV5 below the median value for the cohort). Additional interaction terms were created to test if arterial vascular pruning modified the effect of RVEV on mortality. The reported P values are two sided and P values of less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute) and RStudio (R version 3.3.3). The online supplement provides additional data.

Study Approval

The COPDGene Study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating centers and all participants provided written informed consent.

Results

A total of 3,506 ever-smoking (current or former) COPDGene participants (Table 1) had complete data for these analyses (see Figure E1 in the online supplement). The second half of Table 1 provides the CT-derived features, such as the percent emphysema and vascular morphology.

Table 1.

Clinical, Epidemiologic, and CT-based Features of Study Participants with GOLD Stage 1 or Higher COPD with Complete Data on Vascular and Right Ventricular Morphology (n = 3,506)

| Median or Number | IQR or % | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical and epidemiologic features | ||

| Age, yr | 63.4 | 56.8–70.0 |

| Female, n (%) | 1,539 | 43.9 |

| African American race, n (%) | 687 | 19.6 |

| Height, cm | 170 | 162.6–177.0 |

| FEV1% | 57.3 | 39.6–73.5 |

| Smoking status, current, n (%) | 1,462 | 41.7 |

| Pack-years tobacco | 46 | 34.5–66.0 |

| Measures obtained from CT scan | ||

| TLCCT%* | 102.1 | 91.3–112.4 |

| Percent emphysema | 9.1 | 1.9–31.2 |

| Arterial BV5, ml | 97.0 | 81.0–114.1 |

Definition of abbreviations: BV5 = arterial volume for vessels less than 5 mm2 in cross-section; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT = computed tomography; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; IQR = interquartile range.

n = 3,438.

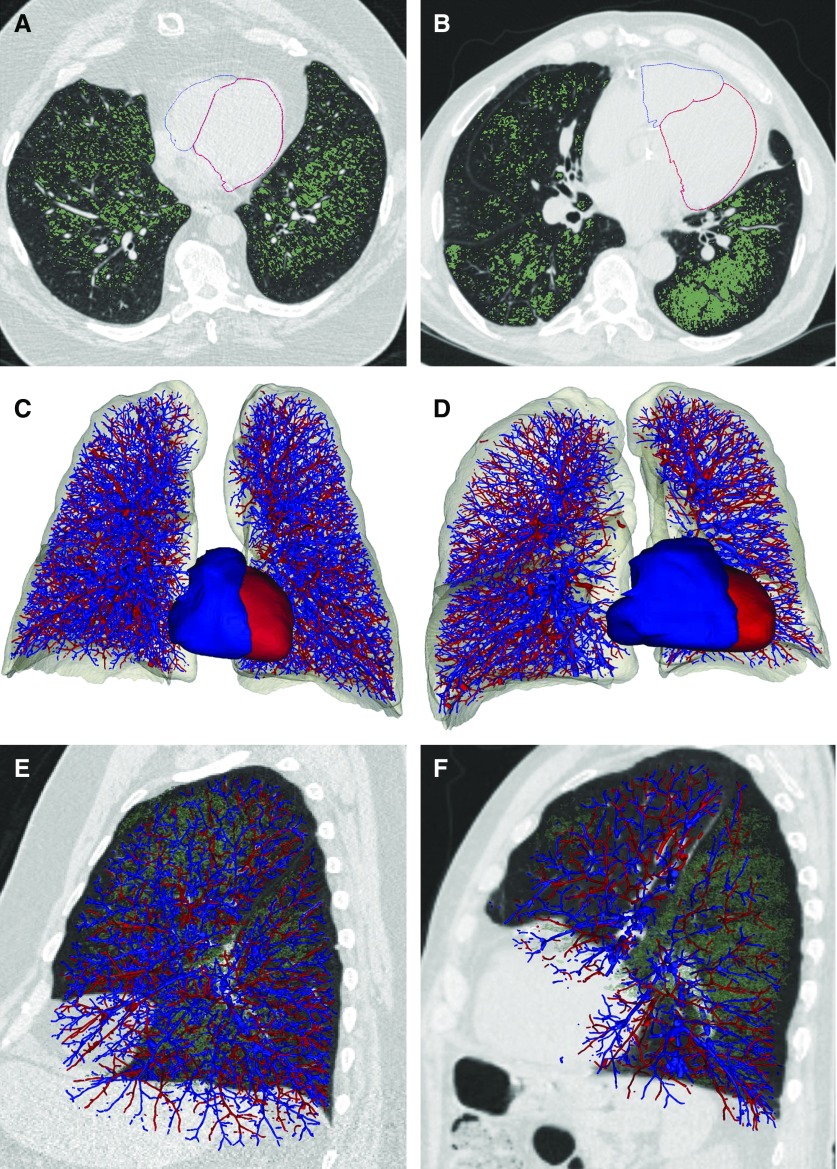

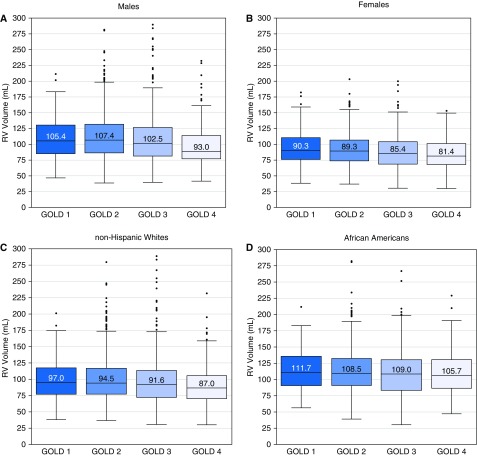

Figure 1 provides examples of the CT-based renderings for the vascular morphology and the epicardial surface of the RV of two participants with similar amounts of CT-determined emphysema but differing volumes of the RVEV. Figure 2 presents the sex- and race-stratified distributions of the RVEV by spirometrically defined GOLD stages. The largest RVEV were found in the GOLD stage 1 subcohorts. There was a 10.5% and 11.9% reduction in the median RVEV between those participants with GOLD stage 1 and those with GOLD stage 4 COPD (P < 0.001 for trend across all GOLD stages) in females and males, respectively. There was a 10.6% and 6.3% reduction in the median RVEV between those participants with GOLD stage 1 and those with GOLD stage 4 COPD (P < 0.001 for trend across all GOLD stages) in non-Hispanic whites and African Americans (P = 0.04), respectively.

Figure 1.

Pulmonary vasculature and right (blue) and left (red) ventricular reconstructions from computed tomography images for two subjects with approximately 20% emphysema on computed tomography scan. (A, C, and E) Subject 1 with 19% emphysema and relative preservation of the distal arterial vascular volume (arterial volume for vessels less than 5 mm2 in cross-section = 131 ml). (B, D, and F) Subject 2 with 18% emphysema and relative loss of the distal arterial vascular volume (arterial volume for vessels less than 5 mm2 in cross-section = 70.8 ml). (A and B) Axial images of the epicardial surface of the right ventricle (RV), which is outlined in blue and the epicardial surface of the left ventricle, which is outlined in red. Emphysema is depicted in green. (C and D) Frontal view of the arterial (blue) and venous vasculature and the surface model of the epicardial (myocardium and chamber) RV volume (blue) and epicardial (myocardium and chamber) left ventricular volume (red). The epicardial (myocardium and chamber) RV volume of Subject 1 is 58.9 ml and the epicardial (myocardium and chamber) RV volume for Subject 2 is 140 ml. (E and F) Sagittal views of the arterial (blue) and venous (red) vasculature of the left lung demonstrating the relative loss of distal arterial vascular volume. Emphysema is shown in green.

Figure 2.

Median (and interquartile range) epicardial (myocardium and chamber) right ventricular volume by sex (top two panels) or race (bottom two panels) and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage. GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; RV = right ventricular.

After review of these trends, we examined the association between distal arterial blood vessel volume and the RVEV. In this model, the arterial BV5 was a significant predictor of RV size where a 10-ml decrease in the distal blood vessel volume was associated with a 1-ml increase in RVEV (P < 0.001) (see Table E1). The percent emphysema was also associated with an increase in the size of the RV. A 10% absolute increase in the percent emphysema on CT scan was associated with a 1-ml increase in the RVEV (P < 0.001).

We then explored these multivariable models stratified by quartiles of the percent emphysema or the FEV1%. The results of these analyses are provided in Tables E2 and E3, respectively. We did this to determine if the relationship between the distal arterial vascular volume and RVEV was linear or varied by disease severity. For both the series of models stratified by the percent emphysema and those stratified by the FEV1%, the arterial BV5 was only protective for an increased RVEV in those with the lowest percent emphysema or greatest FEV1%.

To objectify the magnitude of the highly statistically significant effect of the arterial vascular measures on the RVEV we calculated the effect of distal arterial blood vessel volume in categorical models that included adjustment for measures of emphysema to predict the RVEV. This analysis was performed using tertiles of the distribution of the arterial BV5. In this model the mean adjusted RVEV was 99.1, 101.6, and 102.6 ml in the lowest, middle, and highest tertile of vascular pruning, respectively. For the same amount of emphysema, those participants with the least amount of arterial vascular pruning (Group 1) had an RVEV that was an average of 3.5 ml smaller than those in Group 3 who had the greatest loss of distal arterial vasculature (P = 0.004; P = 0.01 for trend across three categories).

Finally, to explore the clinical implications of the RVEV in those with and without loss of the distal arterial vasculature, we examined its relationship to the 6MWD and mortality. In multivariable analyses, which included the arterial BV5 and the percent emphysema, those with a larger RVEV had a shorter 6MWD (P < 0.001) (Table E4). In subsequent stratified analyses, this association was only present in those with the lowest percent emphysema (Table E5).

The RV epicardial volume also predicted subject death. Those in the highest quartile of RVEV had a 39% greater risk for death than those in the bottom 75% (hazard ratio, 1.39; confidence interval, 1.15–1.67; P < 0.001) (Table 2). Arterial vascular pruning significantly modified the effect of RVEV on morality and stratified analyses revealed that this effect was present only in those with arterial pruning (Table 2 and Figure 3). The remaining three panels of Figure 3 provide comparisons of survival by RV size in those without arterial pruning, survival by arterial pruning in those without RV enlargement, and survival by RVEV in those with arterial pruning.

Table 2.

Association between RVEV and Mortality

| Hazard Ratio | Confidence Interval | P Value | P Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire cohort | 1.39 | 1.15–1.67 | <0.001 | |

| Stratified by arterial pruning | ||||

| Those without arterial vascular pruning | 1.17 | 0.90–1.51 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Those with arterial vascular pruning | 1.65 | 1.27–2.15 | <0.001 | |

Definition of abbreviation: RVEV = epicardial (myocardium and chamber) right ventricular volume.

Multivariable models adjusted for age, sex, race, height (cm), FEV1%, and TLC measured by computed tomography at maximal inflation expressed as a percent of predicted based on sex and race, current smoking status, pack-years, and percent emphysema. Effects expressed as those in the highest quartile of right ventricular volume compared with those in the bottom three quartiles. Pruning dichotomized at median arterial volumes for vessels less than 5 mm2 in cross-section. P interaction based on continuous measures of RVEV. (n = 3,141 with known vital status).

Figure 3.

(Top left) Survival in those participants with right ventricular (RV) enlargement with and without arterial pruning. (Top right) Survival by RV size in those without arterial pruning. (Bottom left) Survival by the presence or absence of arterial pruning in those without enlarged RVs. (Bottom right) Survival in small versus large RV size in those with arterial pruning. An enlarged right ventricle (epicardial [myocardium and chamber] RV volume) is defined as those in the highest quartile of RV volume compared with those in the bottom three quartiles. Pruning is defined as those with an arterial volume for vessels less than 5 mm2 in cross-section less than the median.

Discussion

We observed a complex relationship between emphysema and RV morphology in subjects with COPD. The RVEV was reduced in COPD subjects with more severe expiratory airflow limitation yet within this cohort, after multivariable adjustment including spirometric measures of lung function, those with more emphysema tended to have a larger RVEV. Measures of distal pulmonary arterial vascular morphology modified this latter association where for a given amount of emphysema, loss of or relative preservation of the distal pulmonary arterial vasculature was associated with increases or decreases in RV volumes, respectively. Finally, enlargement of the RVEV was clinically significant and associated with reductions in the 6MWD and in those with arterial pruning, an increased risk of death.

The approximate 10% reduction in RVEV we observed between smokers with GOLD stage 1 and those with GOLD stage 4 COPD is consistent with data provided by transthoracic echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. In a series of 138 subjects with COPD, Watz and colleagues (7) reported that RV and LV area was almost 10% less in subjects with GOLD stage 4 COPD as compared with those with mild expiratory airflow obstruction (GOLD stage 1 COPD). More recently, Kawut and colleagues (35) demonstrated that the RV end-diastolic volume was 17% smaller in subjects with severe compared with mild COPD.

We examined the relationship between distal arterial vascular morphology, emphysema, and RV volume based on our hypothesis that changes in macrovascular vascular morphology have hemodynamic consequence and because of recent work by Grau and colleagues (12). They found that after adjustment for LV volume, objective measures of emphysema, such as tissue on CT, were associated with larger RV end-diastolic volumes and postulated that the admixture of endothelial dysfunction and hypercoagulability as well as vascular destruction found in patients with emphysema resulted in increased pulmonary vascular resistance. We have previously associated CT measures of vascular dropout to elevated pulmonary arterial pressures in severe emphysema (36) and in a smaller investigation of 24 smokers demonstrated that arterial vascular pruning was associated with the RV mass index, end diastolic volume, and ejection fraction (16).

Distal arterial blood vessel volume was inversely related to the RVEV in multivariable models that included CT-based measures of lung volume and emphysema. Loss of intraparenchymal arterial vasculature was associated with an increase in the size of the epicardial volume of the RV measured on CT scan. Subsequent analyses stratified by quartiles of either the percent emphysema or FEV1% suggest that the relationship between the distal arterial vascular volume and RV size is limited to those with the least emphysema or highest FEV1%. These observations are consistent with recent work by Kovacs and colleagues (37), who describe subtypes of patients with COPD and pulmonary hypertension. They report that although mild elevations in pulmonary arterial pressures may be found in those with very severe COPD and extensive emphysematous destruction of the lung parenchyma, those with the “pulmonary vascular phenotype” (more severe pulmonary arterial hypertension) tend to have more moderate expiratory airflow obstruction. Our data further suggest that the distal arterial pruning in those with extensive emphysema may represent a different disease process than distal arterial pruning in those with relatively preserved parenchyma. Additional work is needed to explore this in detail.

Finally, we explored the clinical implications of our measures and found that those with loss of the distal arterial vascular volume and an enlarged RVEV had a reduced 6MWD. RV enlargement was also associated with an increased risk of death, an effect that after stratification was only observed in those with arterial pruning. The aggregate of these models suggest that not only is the development of an increased RV size associated with clinical impairment, but it is particularly so in those who have lost their peripheral arterial pulmonary vasculature. RV enlargement on CT seems to represent some degree of pulmonary hypertension and our data are consistent with previous observations reporting that the presence of pulmonary vascular disease in COPD is an independent predictor of clinical impairment and mortality (38–40).

There are limitations to our investigation that deserve comment. These scans were not acquired with cardiac gating and because they do not uniformly capture images of the ventricle in diastole our measures likely underestimated the true RV volume. Indeed, our measures seem to be consistently 15–20% less than what has been reported for measures of RV end diastolic volume measured by magnetic resonance imaging (35). Despite these limitations our data pertaining to CT measures of emphysema and lung volume are highly consistent with similar work using other modalities to assess ventricular end diastolic volumes. Also, we could not measure thickness of the free ventricular wall. Although one may generally conclude that a larger epicardial volume is prognostic for a larger chamber volume this is likely an imperfect assumption and as such we constrained our investigation to the epicardial surface, which provides excellent contrast for accurate model fitting.

Cor pulmonale and cor pulmonale parvus are the result of competing processes in smokers with an individual’s RV size determined by the relative contribution of several factors including the severity of expiratory airflow obstruction and emphysematous destruction of the lung parenchyma. Our work demonstrates that the loss of distal arterial vasculature is associated with clinically significant increases in RV size and conversely, relative preservation of that vasculature in those with emphysema is protective for the presence and consequences of RV enlargement. These relationships seem to be largely limited to those with less severe COPD. This work suggests that pulmonary vascular remodeling and pruning is not uniformly related to emphysema severity in smokers and therapies focused on vascular disease may improve the cardiovascular outcomes in some patients with less severe COPD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants COPDGene, R01HL089897, and R01HL089856; R01HL116931, R01 HL116473, and R21 HL140422 (R.S.J.E.); R01 HL116473 and R01 HL107246 (G.R.W.); and T32HL007633 (S.Y.A.).

Author Contributions: Conception and design of this study and creation, revision, and final approval of this manuscript: All authors. Analysis and interpretation: G.R.W., S.Y.A., C.E.C., M.T.D., R.K., M.K.H., S.P.B., J.M.W., A.A.D., G.Q.R., A.M.S., G.L.K., J.E.H., A.A., and R.S.J.E. Data acquisition: G.R.W., P.N., S.Y.A., G.V.S.-F., F.N.R., J.C.R., and R.S.J.E. Drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201811-2063OC on February 13, 2019

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: for the COPDGene Investigators

References

- 1.Burrows B, Kettel LJ, Niden AH, Rabinowitz M, Diener CF. Patterns of cardiovascular dysfunction in chronic obstructive lung disease. N Engl J Med. 1972;286:912–918. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197204272861703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler J, Schrijen F, Henriquez A, Polu JM, Albert RK. Cause of the raised wedge pressure on exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:350–354. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sin DD, Man SF. Why are patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at increased risk of cardiovascular diseases? The potential role of systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Circulation. 2003;107:1514–1519. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000056767.69054.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sin DD, Man SF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:8–11. doi: 10.1513/pats.200404-032MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jörgensen K, Houltz E, Westfelt U, Ricksten SE. Left ventricular performance and dimensions in patients with severe emphysema. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:887–892. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000258020.27849.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vassaux C, Torre-Bouscoulet L, Zeineldine S, Cortopassi F, Paz-Díaz H, Celli BR, et al. Effects of hyperinflation on the oxygen pulse as a marker of cardiac performance in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1275–1282. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00151707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watz H, Waschki B, Meyer T, Kretschmar G, Kirsten A, Claussen M, et al. Decreasing cardiac chamber sizes and associated heart dysfunction in COPD: role of hyperinflation. Chest. 2010;138:32–38. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fishman AP. State of the art: chronic cor pulmonale. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;114:775–794. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.114.4.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weitzenblum E. Chronic cor pulmonale. Heart. 2003;89:225–230. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roversi S, Fabbri LM, Sin DD, Hawkins NM, Agustí A. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiac diseases: an urgent need for integrated care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:1319–1336. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0690SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jörgensen K, Müller MF, Nel J, Upton RN, Houltz E, Ricksten SE. Reduced intrathoracic blood volume and left and right ventricular dimensions in patients with severe emphysema: an MRI study. Chest. 2007;131:1050–1057. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grau M, Barr RG, Lima JA, Hoffman EA, Bluemke DA, Carr JJ, et al. Percent emphysema and right ventricular structure and function: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis-Lung and Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis-Right Ventricle Studies. Chest. 2013;144:136–144. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estépar RS, Kinney GL, Black-Shinn JL, Bowler RP, Kindlmann GL, Ross JC, et al. COPDGene Study. Computed tomographic measures of pulmonary vascular morphology in smokers and their clinical implications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:231–239. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201301-0162OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahaghi FN, van Beek EJ, Washko GR. Cardiopulmonary coupling in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the role of imaging. J Thorac Imaging. 2014;29:80–91. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells JM, Iyer AS, Rahaghi FN, Bhatt SP, Gupta H, Denney TS, et al. Pulmonary artery enlargement is associated with right ventricular dysfunction and loss of blood volume in small pulmonary vessels in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:e002546. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.002546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahaghi FN, Wells JM, Come CE, De La Bruere IA, Bhatt SP, Ross JC, et al. and the COPDGene Investigators. Arterial and venous pulmonary vascular morphology and their relationship to findings in cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in smokers. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2016;40:948–952. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahaghi FN, Ross JC, Agarwal M, González G, Come CE, Diaz AA, et al. Pulmonary vascular morphology as an imaging biomarker in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2016;6:70–81. doi: 10.1086/685081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regan EA, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, Make B, Lynch DA, Beaty TH, et al. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD. 2010;7:32–43. doi: 10.3109/15412550903499522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castaldi PJ, San José Estépar R, Mendoza CS, Hersh CP, Laird N, Crapo JD, et al. Distinct quantitative computed tomography emphysema patterns are associated with physiology and function in smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1083–1090. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201305-0873OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castaldi PJ, Cho MH, San José Estépar R, McDonald ML, Laird N, Beaty TH, et al. COPDGene Investigators. Genome-wide association identifies regulatory loci associated with distinct local histogram emphysema patterns. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:399–409. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0569OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ash SY, Harmouche R, Ross JC, Diaz AA, Hunninghake GM, Putman RK, et al. The objective identification and quantification of interstitial lung abnormalities in smokers. Acad Radiol. 2017;24:941–946. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2016.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ash SY, Harmouche R, Putman RK, Ross JC, Diaz AA, Hunninghake GM, et al. COPDGene Investigators. Clinical and genetic associations of objectively identified interstitial changes in smokers. Chest. 2017;152:780–791. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.04.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ash SY, Harmouche R, Putman RK, Ross JC, Martinez FJ, Choi AM, et al. COPDGene Investigators. Association between acute respiratory disease events and the MUC5B promoter polymorphism in smokers. Thorax. 2018;73:1071–1074. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-211208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ash SY, Harmouche R, Ross JC, Diaz AA, Rahaghi FN, Vegas Sanchez-Ferrero G, et al. COPDGene Investigators. Interstitial features at chest CT enhance the deleterious effects of emphysema in the COPDGene cohort. Radiology. 2018;288:600–609. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018172688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahaghi FN, Come CE, Ross J, Harmouche R, Diaz AA, Estepar RS, et al. Morphologic response of the pulmonary vasculature to endoscopic lung volume reduction. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis (Miami) 2015;2:214–222. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.2.3.2014.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nardelli P, Jimenez-Carretero D, Bermejo-Pelaez D, Washko GR, Rahaghi FN, Ledesma-Carbayo MJ, et al. Pulmonary artery-vein classification in CT images using deep learning. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2018;37:2428–2440. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2018.2833385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahaghi FN, Vegas-Sanchez-Ferrero G, Minhas JK, Come CE, De La Bruere I, Wells JM, et al. COPDGene Investigators. Ventricular geometry from non-contrast non-ECG-gated CT scans: an imaging marker of cardiopulmonary disease in smokers. Acad Radiol. 2017;24:594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhatt SP, Vegas-Sánchez-Ferrero G, Rahaghi FN, MacLean ES, Gonzalez-Serrano G, Come CE, et al. Cardiac morphometry on computed tomography and exacerbation reduction with β-blocker therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1484–1488. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0399LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Thoracic Society. Standardization of spirometry, 1994 update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1107–1136. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crapo RO, Morris AH, Gardner RM. Reference spirometric values using techniques and equipment that meet ATS recommendations. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;123:659–664. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1981.123.6.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, et al. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Putman RK, Hatabu H, Araki T, Gudmundsson G, Gao W, Nishino M, et al. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) Investigators; COPDGene Investigators. Association between interstitial lung abnormalities and all-cause mortality. JAMA. 2016;315:672–681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahrer JM, Magel RC. A comparison of tests for the k-sample, non-decreasing alternative. Stat Med. 1995;14:863–871. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoenfeld D. Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika. 1982;69:239–241. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawut SM, Poor HD, Parikh MA, Hueper K, Smith BM, Bluemke DA, et al. Cor pulmonale parvus in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema: the MESA COPD study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2000–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuoka S, Washko GR, Yamashiro T, Estepar RS, Diaz A, Silverman EK, et al. National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. Pulmonary hypertension and computed tomography measurement of small pulmonary vessels in severe emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:218–225. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200908-1189OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovacs G, Agusti A, Barberà JA, Celli B, Criner G, Humbert M, et al. Pulmonary vascular involvement in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: is there a pulmonary vascular phenotype? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:1000–1011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201801-0095PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kessler R, Faller M, Weitzenblum E, Chaouat A, Aykut A, Ducoloné A, et al. “Natural history” of pulmonary hypertension in a series of 131 patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:219–224. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.2.2006129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oswald-Mammosser M, Weitzenblum E, Quoix E, Moser G, Chaouat A, Charpentier C, et al. Prognostic factors in COPD patients receiving long-term oxygen therapy: importance of pulmonary artery pressure. Chest. 1995;107:1193–1198. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.5.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cuttica MJ, Kalhan R, Shlobin OA, Ahmad S, Gladwin M, Machado RF, et al. Categorization and impact of pulmonary hypertension in patients with advanced COPD. Respir Med. 2010;104:1877–1882. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.