Abstract

In this pilot study, we analyzed effects of transcranial photobiomodulation (tPBM, 1267 nm, 32 J/cm2) on clearance of beta-amyloid (Aβ) from the mouse brain. The immunohistochemical and confocal data clearly demonstrate the significant reduction of deposition of Aβ plaques in mice after tPBM vs. untreated animals. The behavior tests showed that tPBM improved the cognitive, memory and neurological status of mice with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Using of our original method based on optical coherence tomography (OCT) analysis of clearance of gold nanorods (GNRs) from the brain, we proposed possible mechanism underlying tPBM-stimulating effects on clearance of Aβ via the lymphatic system of the brain and the neck. These results open breakthrough strategies for a non-pharmacological therapy of Alzheimer’s disease and clearly demonstrate that tPBM might be a promising therapeutic target for preventing or delaying Alzheimer’s disease.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia and the most common neurodegenerative disease, affecting millions of predominantly elderly individuals worldwide. In addition, this chronic disease is one of the major contributors to disability and causes increases in the burdens of patients and the families of patients, as well as of the health and social care systems [1]. In 2013, 6.8 million people in the U.S. had been diagnosed with dementia. Of these, 5 million had a diagnosis of Alzheimer's. By 2050, the numbers are expected to double [2].

In 1991, an “amyloid hypothesis” was proposed [3,4]. According to this theory, extracellular deposits - senile plaques from an abnormal β-amyloid protein appear in AD. The formation of Aβ occurs due to two consecutive end proteolysis acting with β-and γ-secretases of the β-amyloid protein precursor. Intracellular deposits are neurofibrillary plexuses from the hyperphosphorylated tau protein (τ-protein). Aggregation of the τ-protein is more common in the somatodendritic part of the neurons. These deposits contribute to a reduction in the number of synapses and the development of cognitive deficit [5,6]. The factors of the “amyloid cascade” developing in AD are microglial inflammatory reactions, activation of the peroxide lipid, disintegration of microtubules and the entire transport system of the neuron [7]. The hypothesis on the role of Aβ and τ-protein in the onset and development of AD has been developed in numerous experimental studies [8–13].

Currently, there are no pharmacological drugs that provide an effective therapy of AD and limit the development of cognitive impairment [14]. Note that pharmaceutical companies such as Biogen, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer announced the cancellation of funding for the synthesis of antibodies for the treatment of AD due to the failure of clinical trials [15]. Obviously, in the next couple of decades, the main strategies for a treatment of AD will be non-invasive methods of stimulation of clearance of the toxic Aβfrom the brain tissues. The first progressive step in this direction was made last year, when it was discovered that the meningeal lymphatic (MLVs) dysfunction may be an aggravating factor in AD pathology and augmentation of MLV function was proposed as therapeutic target for preventing of age-associated neurological diseases [16].

The transcranial photobiomodulation (tPBM) is considered as a possible novel non-pharmacological and non-invasive therapeutic strategy for prevention or delay of AD [17,18]. A number of reviews have focused on application of tPBM for treatment of AD [19–24], depression [19–22,25], and traumatic brain injuries [19–22,24].

In the last years, there is accumulating evidence suggesting that tPBM can reduce Aβ-mediated hippocampal neurodegeneration, memory impairments in rodents, inhibits Aβ-induced brain cell apoptosis and causes a reduction in Aβ plaques in the cerebral cortex [26–29].

Considering these facts, we hypothesize that tPBM due to a good penetration into the brain cortex and even into deep brain regions can stimulate MLVs that might be one of the mechanisms underlings a discovered therapy of AD by tPBM. To test our idea, here we studied tPBM of clearance of Aβ from the brain of mice with AD using 1267 nm laser stimulation of lymphatic drainage of the brain. For the first time 1267 nm laser was used in in vitro experiments to affect cancer cells [30].

2. Methods

2.1. Subject

Experiments were performed in mongrel male mice (25 g, total number - 140) in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996), and the protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Saratov State University (Protocol 7, 07.02.2017).The rats were housed at 25 ± 2°C, 55% humidity, and 12:12 h light – dark cycle. Food and water were given ad libitum.

The experiments were performed in the following groups: 1) the control group including intact mice; 2) sham mice; 3) untreated mice with AD without tPBM; 4) mice with AD received tPBM. N = 7 in each group in four sessions of experiments: selection of optimal tPBM dose (n = 28); histological analysis (n = 28), confocal imaging (n = 28), OCT monitoring, (n = 56).

2.2. An animal model of Alzheimer disease in mice

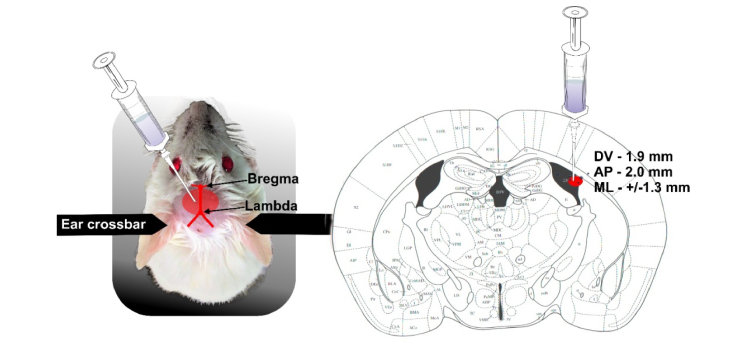

To induce AD in mice, we used the injection of Aβ(1-42) peptide (1 μL, 200 μmol) in the CA1 field of the hippocampus bilateral. Aβ(1–42) was dissolved in phosphate saline buffer (PBS) and then incubated for 5–7 days at 37 °C to induce fibril formation [31–33]. The mice were anaesthetized by 1% isoflurane at 1 L∕ min N2O∕O2 − 70∶30, and fixed in a stereotactic frame. The scalp was removed and the skull surface was dried by clean compressed air. Injection of Aβwas performed with a 5 µL Hamilton syringe with a 29-G needle at a rate of 0.1μL/min (Bonaduz, Switzerland) and stereotactic coordinates (AP-2.0 mm; ML+/−1.3 mm; DV-1.9 mm) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The scheme of intrahippocampal injection of Aβ(1-42) peptide in mice: a) mice preparation after shaving of head and exposure the skin over the skull; b) stereotaxic coordinates for injection of Aβ into the CA1 subregion of the hippocampus of an adult mouse.

2.3. Photomodulation of Aβ clearance from the brain

The mice were recovered after the surgery procedure of injection of Aβ during 3 days. Afterward, mice were treated by tPBM during 9 days each second day under inhalation anesthesia (1% isoflurane at 1 L∕ min N2O∕O2 − 70∶30). The mice with shaved head were fixed in stereotaxic frame and irradiated in the area of the frontal cortex using the sequence of: 17 min – irradiation, 5 min – pause during 61min.

A fiber bragg rating wavelength locked a high power laser diode (LD-1267-FBG-350, Innolume, Dortmund, Germany) emitting at 1267 nm was used as a source of irradiation. The laser diode was pigtailed with a single mode distal fiber ended by the collimation optics to provide a 5 mm beam diameter at the specimen. Four laser output power densities were used at this study – 50, 100, 150, and 200 mW/cm2 (laser power was measured after the collimation lens). For taken power densities and exposure time of 1020 seconds, the following laser fluences were delivered to the surface of the brain during the experiments: 51 J/cm2, 102 J/cm2, 153 J/cm2, 204 J/cm2, which were converted into 18 J/cm2, 25 J/cm2, 32 J/cm2, 39 J/cm2 at the brain’s surface according to collimated transmission data.

The heating of the brain tissue caused by exposure to light was monitored by using a thermocouple data logger (Pico Technology, USB TC-08, Cambridge shire, UK).

2.4. Immunohistochemical (IHC) assay

The mice were euthanized with an intraperitoneal injection of a lethal dose of ketamine and xylazine and intracardially perfused with 0.1 M of PBS for 5 min.

For a confocal analysis of Aβ depositions, the brains were removed and fixed in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde for two day and in 30% sucrose for another day. The Aβ plaques on free-floating sections were evaluated using the standard method of simultaneously combined staining (Abcam Protocol). The brain tissue was cut into 50-μm thick slices on a vibratome (Leica VT 1000S Microsystem) and then were blocked in 10% BSA/0.2% Triton X-100/PBS for 2 h, then incubated overnight at 4°C with anti- Aβ antibody (1:500; Abcam, ab182136, Cambridge, USA) followed by 2 h at room temperature. After several rinses in PBS, the slides were incubated for 2h at room temperature with fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies on 1% BSA/0.2% Triton X-100 /PBS (1:500; Goat A/Rb, Alexa 555- Abcam, UK, ab150078). A confocal microscopy of the cerebral cortex of the mice was carried out using a confocal laser scanning microscope Leica SP5 (Leica, Germany). ImageJ was used for image data processing and analysis. The areas of expression of antigens were calculated using the plugin “Analyze Particles” in the “Analyze” tab, which calculates the total area of antigen-expressing tissue elements - the indicator “Total Area”. In all cases, 10 regions of interest were analyzed. Quantification is given in square microns per slice.

For histological analysis of Aβ depositions in the cortex, we used the protocol for the immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis with anti- Aβ antibody (1:500; Abcam, ab182136, Cambridge, USA).The tissue samples were fixed with formaldehyde and, after a routine processing, were embedded into a paraffin block. Then the samples were sectioned into 3- to 5-μm sections on a vibratome (Leica VT 1000S Microsystem); the sections were attached to poly-L-lysine coated glass slides; they were dried at 37°C for 24 h; and they were sequentially incubated in xylene (three times, 3 min each), 96% ethanol (three times, 3 min each), 80% ethanol (two times, 3 min each), and distilled water (three times, 3 min each). The IHC reaction was visualized with a REVEAL—BiotinFree Polyvalent diaminobenzidine kit (Spring Bioscience). Endogenous peroxidases were blocked by adding 0.3% hydrogen peroxide to the sections for 10 min followed by washing of sections in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The antigen retrieval was conducted using a microwave oven in an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-buffer pH 9.0, and a nonspecific background staining was blocked in PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.5% casein for 10 min, after which the sections were washed in PBS for 5 min. Further, the sections were incubated in a humid chamber with diluted anti- Aβ antibody (1:500; Abcam, ab182136, Cambridge, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. After that, the sections were washed in PBS, incubated with secondary horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat antirabbit antibodies for 15 min, again washed in PBS, counterstained with hematoxylin for 1 min, washed again in water, dehydrated in graded alcohols (three times, 3 min each) and then in xylene (three times, 3 min each), and finally embedded into Canadian balm. The histological sections were evaluated by light microscopy using a Mikrovizor μVizo-103 digital image medical analysis system (LOMO, Russia).Approximately 10 slices per animal were imaged.

The quantitative analysis of the results of IHC staining on Aβ marker was carried out on a microscopic system with automatic analysis of the obtained photos of Ariol SL50 (Genetix, UK).The total area of IHC was determined with the software module PathVysion (Music, Inc. Applied Imaging).

2.5. OCT monitoring of GNR accumulation in dcLN

Gold nanorods (GNRs) coated with thiolated polyethylene glycol (5 µL at a rate of 0.1 µL/min, the GNRs average diameter and length of 16 ± 3 nm and 92 ± 17 nm) were injected in the cortex (AP - 1.06 mm; DV - 1.5 mm; ML - 1.5 mm), the hippocampus (AP - 2.0 mm; ML - 1.3 mm; DV - 1.9 mm), the cisterna magna, and the right lateral ventricle (AP - 1.06 mm; DV – 2.0 mm; ML – 2.0 mm) 30 min before tPBM. Afterwards, OCT imaging of dcLNs was performed during the next 1h for each mouse. The GNR was used with a concentration of 500 µg/ml, the injected dose of 5 μl containing 2.5 μg Au.

In this study, we used a commercial spectral domain OCT Thorlabs GANYMEDE (central wavelength 930 nm, spectral band 150 nm, axial resolution 4.4 µm in water, and maximal imaging depth 2.7 mm). To provide a lateral resolution of about 13 µm within the depth of the field, the LSM02 objective was used. A-scan rate of the OCT system was set to 30 kHz. Each B-scan consists of 2048 A-scans to ensure an appropriate spatial sampling.

At each location 50 B-scans were taken. Logarithmic intensity values were converted into the linear scale using this equation: . This stack was then stabilized with respect to the reference region (emptiness in the lymphatic node). After stabilization process B-scans were averaged to increase SNR and accuracy of the measurements.

Since a lymph is optically transparent (low absorption and scattering) in a broad range of wavelengths, “empty” cavities exist in the resulting OCT image of the lymphatic node with a background signal-to-noise ratio inside. In order to image the lymph dynamic accumulation within these cavities, a suspension of GNRs was used as a contrast agent, for which the OCT signal intensity is proportional to the nanoparticle concentration. By tracking the OCT signal temporal alterations inside the node’s cavity, we could confirm the clearance pathways and quantify its relative speed. The OCT recordings were performed under inhalation anesthesia (1% isoflurane at 1 L∕ min N2O∕O2 − 70∶30).

The GNRs content in the deep cervical lymph nodes (dcLNs) was evaluated by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) on a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). The AAS of GNRs was performed after OCT monitoring of GNRs in dcLNs obtained from the same mice, which were used for OCT-GNRs measurements. The AAS results were calculated on the relative weight of the tissues (the brain tissue mass was in the range of 300-400 mg, lymph nodes - 10-30 mg).

2.6. Behavior, neurological and cognitive tests

The behavioral tests were conducted in intact mice (the control group), 3 days after the modeling of AD (the sham group, in untreated mice with AD) during 9 days each second day. Cages and equipment for these tests were cleaned between tests to remove scents. The neurobehavioral status of mice was obtained by the neurological severity score (NSS) [34,35]. It consists of 9 individual parameters in points, including tasks on motor function, alertness and physiological behavior. One point is assigned for failing the task, so a normal healthy animal should have 0 points for all points of the scale. The object recognition test was used for memory evaluation [36]. The test was conducted in one day. Two identical objects (cubes) were placed in a cage for an animal for 10 min. Then one cube was changed to an object unfamiliar earlier (ball). There was a second 10-min session. During both sessions, the time (in seconds) spent on exploring new and familiar objects was recorded. Animals that spent less than 20 seconds studying two subjects were excluded from the study.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The results were reported as a mean value ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences from the initial level in the same group were evaluated by the Wilcoxon test. Intergroup differences were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney test and the ANOVA-2 (post hoc analysis with the Duncan’s rank test). The significance levels were set at p <0.05 for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. tPBM reduces accumulation of Aβ in the mouse brain

In the first step, we selected the optimal 1267 nm fluence on the brain surface for tPBM. The fluence (18-25-32-39 J/cm2) of 1267 nm were selected randomly. The criteria for optimal parameters of tPBM are safe laser impact on morphological structures of the brain tissues, no essential heating of the scalp and statistically significant decrease in the Aβ distribution in the mouse brain. Table 1 illustrates that 1267 nm (39 J/cm2) effectively reduced the Aβ accumulation in the brain. However, this effect was associated with injuries of dura matter and arachnoid membranes (winding form of veins and capillaries; formation of vasogenic edema; data not presented) as well as with a scalp temperature rise of 2°CThe lower 1267 nm fluences (18 J/cm2 and 25 J/cm2) were ineffective against the Aβ accumulation in the brain. The 1267 nm (32 J/cm2) was selected as an optimal laser fluence because it was not associated with an increase in a scalp temperature or morphological changes of the brain tissues and was effective for the decline of Aβ depositions in the brain.

Table 1. Different 1267nm fluence effects on scalp temperature, morphological changes in the brain meninges and Aβ accumulation in the brain.

| Laser 1267 nm fluence on the brain surface, J/cm2 | Scalp temperature | Morphological changes in the brain meninges | Aβ decline of accumulation in the brain tissues, µm2/slice |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 32.2 ± 1.2 | - | 95 127 ± 117 |

| 25 | 31.3 ± 2.9 | - | 96 114 ± 102 |

| 32 | 33.0 ± 1.7 | - | 21 141 ± 45 * † |

| 39 | 37.2 ± 1.2 * † | winding form of veins and capillaries; formation of vasogenic edema | 17 103 ± 37 * † |

- p<0.001 vs. the low tPBM doses 18J/cm2 and 25J/cm2, respectively; n = 7 for each group.

In the second step, we studied the development of AD in mice after injection of Aβ in the hippocampus and analyzed effects of tPBM on Aβ distribution in the brain tissues.

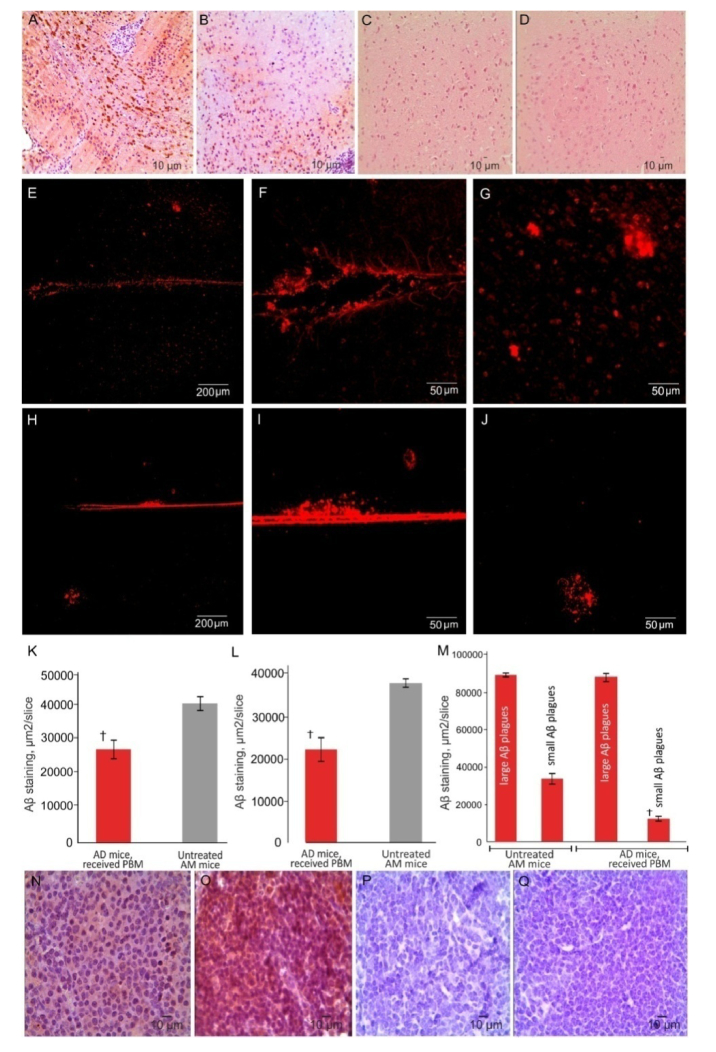

IHC and the confocal analysis of Aβ deposition in the brain tissues demonstrated an effective development of AD in mice. Indeed, Aβ plaques were clearly observed in different regions of the brain of mice (predominantly in the hippocampus and in the cortex) after intrahippocampal injection of Aβ (Fig. 2(A)). The confocal data reveled also the presence of small and large Aβplaques in the brain tissues in the same mice (Figs. 2(E-G)).The behavior analysis confirmed ex vivo data and demonstrated the development of memory loss and neurocognitive failure in mice after injection of Aβ in the hippocampus (Figs. 3(A) and 3(B)). There were no Aβplaques in the brain tissues and behavior changes in the sham and control groups (Figs. 3(A) and 3(B)).

Fig. 2.

PBM effects on distribution of Aβ deposition in the mouse brain: A-D – ICH imaging of Aβ depositions in the brain tissues in untreated mice with AD (A), in mice with AD after PBM (B), in the shem group (C) and in intact mice from the control group (D); E-M – Confocal and quantitative analysis of Aβ distribution in the brain tissues of untreated mice with AD (E-G), in mice with AD after PBM (H-J); K-M – quantitative analysis of presence of Aβ plagues in tested tissues in untreated mice with AD and mice with AD, received PBM: K – in the brain (ICH data); L - in dcLN (ICH data); M – in the brain (small and large Aβ plagues, confocal data); N-Q – ICH data of Aβ depositions in dcLNs in untreated mice with AD (N), in mice with AD, received PBM (O), in the shem group (P) and in intact mice from the control group (Q). n = 7 for each group, at least 10 individual tissue sections taken for each animal. † - p<0.001 between groups.

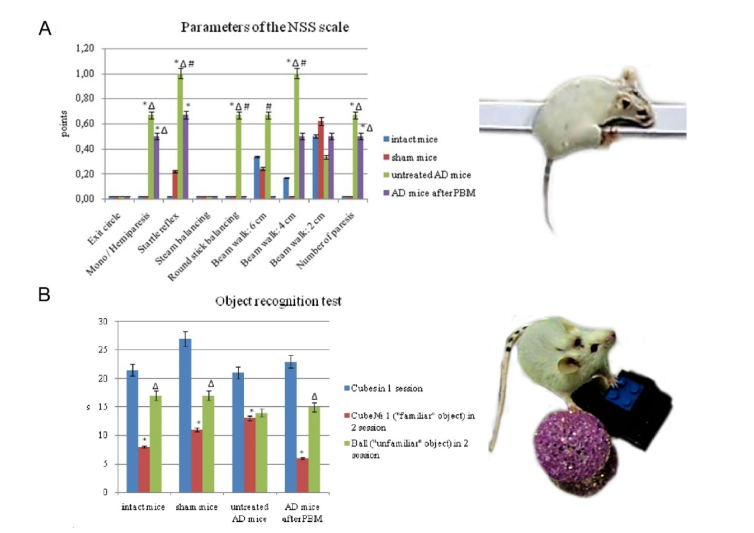

Fig. 3.

The memory and neurological tests: A - the assessment of the neurobehavioral status of mice on the NSS scale (* - p<0.05 vs. intact mice; Δ - p<0.05 vs. sham mice; #- between untreated AD mice and AD mice received tPBM); B - the оbject recognition test, reflecting the processes of learning, recognition and memorization (* - p<0.05 vs. cubes in 1 session; Δ - p<0.05 vs. cube Nº1 («familiar» object) in 2 session). n = 7 for each group.

The ICH study of tPBM effects on the accumulation of Aβ deposition in the brain tissues clearly show a significant attenuation of Aβ deposition in the brain tissues compared with untreated mice (Figs. 2(A), 2(B), and 2(K)). The confocal analysis revealed that tPBM reduced predominantly the density of small Aβplaques, while the large Aβplaques did not differ between treated and untreated groups (Figure E-J, M).

The accumulation of Aβ in the brain was accompanied by the appearance of Aβ plaques in the dcLNs that was more pronounced in mice with AD, received tPBM, compared with untreated mice (Fig. 2(N) and (O)). No Aβ depositions were observed in dcLNs in the sham and in the control groups (Fig. 2(P) and (Q)).

3.2. tPBM prevents memory and neurological deficit

The assessment of the neurobehavioral status of mice using the NSS scale uncovered significant neurological deficit in mice with AD compared with the intact and sham mice (3.67 ± 0.58 vs. 1.00 ± 1.26; 1.08 ± 0.87, p<0.05, respectively) (Fig. 3(A)). The mice with AD demonstrated sensory, motor, and coordination disorders by the following indicators: mono / hemiparesis, startle reflex, round stick balancing, beam walk (4 cm), number of paresis (Fig. 3(A)). The mice with AD, which received tPBM, performed the following tests: startle reflex, round stick balancing, and beam walk (6 cm; 4 cm) better than untreated mice with AD suggesting aboutthe improvement of the neurological status in mice after the course of tPBM (Fig. 3(A))

The object recognition test revealed the memory deficit in untreated mice with AD compared with the intact and sham mice (Fig. 3(B)). Indeed, they demonstrated the same time of sniffing of new and presented before object that indicates a memory impairment in these animals. The tPBM significantly improved the memory of mice with AD. So, these animals spent more time of sniffing for new object than for already known one for them (Fig. 3(B))

Thus, these results clearly uncover the development of memory and neurological deficit in mice with AD that was significantly improved by tPBM.

3.3. tPBM increases lymphatic drainage: OCT data of clearance of GNRs from the brain

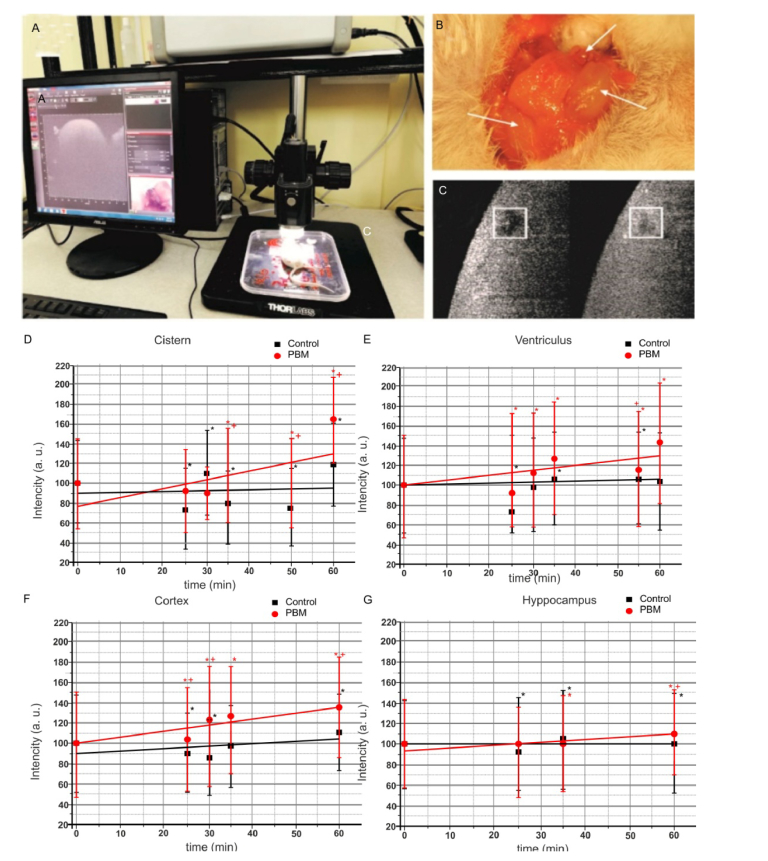

Here we analyzed tPBM effects on clearance of GNRs from the brain into cervical lymphatics using OCT in vivo monitoring of rate of GNRs accumulation in right dcLN. Figure 4 illustrates the design of the experiment (A), the anatomical position of the deep and superficial lymph nodes in the neck of mouse (B) and gives an example of OCT imaging of dcLN in time (C, squares left and right demonstrate OCT imaging immediately and 60 min after start of recording, brighter means more high level of GNRs in dcLN).

Fig. 4.

The OCT monitoring of the rate of accumulation of GNRs in dcLN in untreated mice and in mice received tPBM: a - scheme of OCT measurement of GNRs the accumulation in dcLN; c – anatomical position of the deep and superficial cervical lymph nodes in the neck of mice; c – example of OCT image of dcLN before and 60 min after start of OCT recording (more bright square means more high level of GNRs in dcLN); d-g - OCT data of rate of accumulation of GNRs in dcLNs in untreated mice (black line), in mice received PBM (red line) after GNRs injection into: d) the cisterna magna; e) the right lateral ventricle; i) the cortex; g) the hippocampus. * - p<0.05 vs. basal level; † - p<0.05 between groups. n = 7 in each group.

Our results uncover that the rate of GNRs clearance from the brain depends on the anatomical area of injection of GNRs. Indeed, the clearance of GNRs from the cortex, in the right lateral ventricle or in the cisterna magna was faster than from the hippocampus (0.193 ± 0.013, 0.159 ± 0.062, 0.139 ± 0.083 vs. 0.035 ± 0.004, p<0.05, respectively).

Figure 4(D-G) clearly shows that PBM significantly increased the rate of GNRs accumulation in dcLN. So, PBM-activated clearance of GNRs from the cortex was 3.7-fold higher compared with untreated mice (0.707 ± 0.014 vs. 0.193 ± 0.013, p<0.01); from the lateral ventricle – 3.9-fold (0.631 ± 0.017 vs. 0.159 ± 0.062, p<0.05); from the cisterna magna – 6.7-fold (0.933 ± 0.056 vs. 0.139 ± 0.083, p<0.001); and from the hippocampus – 9.3-fold (0.325 ± 0.060 vs. 0.035 ± 0.004, p<0.001).

The results of AAS, which demonstrate the level of GNR sin dcLN, were correlated with OCT data and confirmed that the clearance of GNRs depends on the anatomical area of the brain of their injection in both untreated mice and in mice received PBM. So, the level of GNRs in dcLN after their injection in the cortex was 3.7-fold higher in PBM-group vs. untreated group(5.8 ± 1.1µg/g tissue vs.21.5 ± 1.6 µg/g tissue, p<0.001); in the right lateral ventricle – 4.9-fold (4.9 ± 1.2 µg/g tissue vs. 22.0 ± 1.8 µg/g tissue, p<0.001); in the cisterna magna – 7.6-fold (3.3 ± 0.7 µg/g tissue vs.25.3 ± 1.9 µg/g tissue, p<0.001); in the hippocampus – 16.8-fold (2.0 ± 0.9 vs. 33.7 ± 2.9, p<0.001).

4. Discussion

In this pilot study we analyzed the photomodulation of clearance of Aβ from the brain of mice with AD using tPBM1267 nm (32 J/cm2) on: 1) accumulation of Aβ in the brain tissues during formation of AD and 2) the lymphatic drainage in healthy mice.

To induce AD, we used an intrahippocampal injection of Aβ, which represents one of the most useful animal models of AD [31–33]. Since none of available animal models fully represents the key pathological hallmarks of AD, stereotaxic Aβ(1-42) infusion provides an alternative paradigm. This model is the best-suited one for short-term studies focusing on the effects of Aβ (1-42) on a specific brain region and on analysis of Aβ clearance [31–33].

ICH and the confocal data clearly demonstrated the development of AD in mice that was accompanied by a significant accumulation of Aβ small and large depositions in different regions of the brain, predominantly in the cortex and hippocampus (site of Aβ injection). The behavior and neurological tests such as a test for the recognition of new object and NSS scale, confirmed the ex vivo data and gave indicating memory loss, cognitive failure and neurological disorders in mice with AD. Thus, intrahippocampal injection of Aβ was accompanied by the development of markers of AD such as the accumulation of Aβ injection in the brain with neurological, cognitive and memory deficit [2–8,37,38].

PBM was discovered 50 years ago and during the last past decade, PBM has been widely used to study neuropsychological diseases such as AD [26–29,39–46], depression-like behavior [47,48], Parkinson’s disease [49], stroke [50,51], or traumatic brain injuries [52,53]. PDM applies to stimulate ATP biosynthesis, the level of mitochondrial complex, and neurogenesis [19–22]. A number of reviews have focused on application of PBM for a treatment of AD [19–24], depression [19–22,25], or traumatic brain injuries [19–22,24].

For tPBM the laser 1267 nm was selected due to its ability to generate singlet oxygen directly without photosensitizers and with deeper penetration into the brain tissue compared with the other wavelengths (600-800 nm), which are usually used for PDT [30,54–56].

Using PBM based on 9 days course of transcranial 1267nm (32 J/cm2) effects on the mouse brain, we clearly demonstrate that PBM significantly reduced Aβ depositions in the brain as well as improved the neurological, cognitive and memory status of treated AD mice compared with untreated AD animals. Our results are consistent with other clinical and experimental data suggesting effectiveness of PBM for treatment of AD. Indeed, there is accumulating evidence, which was suggested that tPBM significantly reduces Aβ-mediated hippocampal neurodegeneration and memory impairments in rodents [26,28]. Other experimental work demonstrates that tPBM inhibits Aβ-induced brain cell apoptosis and causes a reduction in Aβ plaques in the cerebral cortex [27,29]. Clinical data suggest that tPBM decreases Aβ aggregates in human neoblastoma cells [44].

However, there are a large number of tPBM parameters such as wavelength, power density, treatment time, pulsing and repetition rate that make it difficult to compare between different results [22].

The mechanisms underlying tPBM treatment of AD remain unclear. In the peripheral tissues tPBM causes a reduction in the volume of tissues and anti-inflammatory effects probably due to nitric oxide (NO) modulation of lymphatic vessels constriction and lymph flow [57–62]. There the several reviews, which cover the mechanisms of tPBM that operate on molecular, cellular and tissue levels [19–22]. There is the hypothesis that mitochondria might be initial events, which after light effects can increase synthesis of ATP, reactive oxygen species, intracellular Ca2 + , and release NO [19–22,62]. These initial factors activate transcriptional mechanisms then lead to the expression of many protective, anti-oxidant, anti-apoptotic and anti-proliferation gene production [57–63].

In last years it has been shown that MLVs dysfunction may be an aggravating factor in AD pathology [16]. Authors proposed that augmentation of MLVs function might be a promising therapeutic target for preventing or delaying of AD. In our previous work we have clearly demonstrated that MLV system is a pathway for clearance of molecules crossing the opened BBB [64,65]. Based on these facts, in the current study, we tested the idea that tPBM might stimulate lymphatic drainage as a mechanism of clearance of molecules from the brain, which we discussed in our recent review [66]. Using OCT in vivo monitoring of GNRs accumulation in dcLN (confirmed by ASS data) after its injection in the different regions of the brain, we uncover that tPBM significantly increases the clearance of GNRs from both deep (hippocampus, ventriculus) and superficial (cisterna magna, cortex) fields of the brain. The tPBM-related stimulation of GNRs clearance from the brain and its accumulation in dcLN suggests about tPBM-induced lymphatic drainage that might be one of possible mechanisms underlying tPBM-reducing of Aβ plaques in the brain and an improvement of the neurological, cognitive and memory status of mice with AD.

5. Conclusion

The results of this pilot study clearly demonstrate that 9 days course of tPBM (1267 nm, 32 J/cm2) reduces Aβplaques in the brain of mice with AD and improved the memory and neurocognitive deficit. The tPBM-mediated stimulation of lymphatic drainage might be one of mechanism underlying tPBM elimination of Aβ from the brain. These data clearly show that tPBM might be a promising novel therapeutic target for preventing or delaying AD.

Acknowledgments

We thank research center “Symbiosis” IBPPM RAS for support in data acquisition (AS, confocal) in the framework of Research Project no. АААА-А17-117102740097-1.

Funding

Russian Science Foundation (RSF) (18-75-10033).

Disclosures

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this article.

References

- 1.Santini Z. I., Koyanagi A., Tyrovolas S., Haro J. M., Fiori K. L., Uwakwa R., Thiyagarajan J. A., Webber M., Prince M., Prina A. M., “Social network typologies and mortality risk among older people in China, India, and Latin America: A 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based cohort study,” Soc. Sci. Med. 147, 134–143 (2015). 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ubhi K., Masliah E., “Alzheimer’s disease: recent advances and future perspectives,” J. Alzheimers Dis. 33(Suppl 1), S185–S194 (2012). 10.3233/JAD-2012-129028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy J., Allsop D., “Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease,” Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 12(10), 383–388 (1991). 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mudher A., Lovestone S., “Alzheimer’s disease-do tauists and baptists finally shake hands?” Trends Neurosci. 25(1), 22–26 (2002). 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)02031-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardy J., Selkoe D. J., “The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics,” Science 297(5580), 353–356 (2002). 10.1126/science.1072994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farooque A. A., “Neurochemical aspects of neurodegenerative disease. Neurochemical aspects of neurotraumatic and neurodegenerative diseases,”Farooque A. A., ed. (Springer, 2010), pp. 249–324. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stavrovskaya A. V., Yamshchikoval N. G., Ol’shanskiyl A. S., Babkinl G. A., Illarioshkinl S. N., “Evaluation of the effects of new peptide compounds in experimental animals with a toxic model of Alzheimer’s disease,” Ann. Clin. Exp. Neurol. 10, 33–42 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald M. P., Dahl E. E., Overmier J. B., Mantyh P., Cleary J., “Effects of an exogenous β-amyloid peptide on retention for spatial learning,” Behav. Neural Biol. 62(1), 60–67 (1994). 10.1016/S0163-1047(05)80059-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamada K., Nabeshima T., “Animal models of Alzheimer’s disease and evaluation of anti-dementia drugs,” Pharmacol. Ther. 88(2), 93–113 (2000). 10.1016/S0163-7258(00)00081-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardy J., “The amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: a critical reappraisal,” J. Neurochem. 110(4), 1129–1134 (2009). 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iqbal K., Bolognin S., Wang X., Basurto-Islas G., Blanchard J., Tung Y. C., “Animal models of the sporadic form of Alzheimer’s disease: focus on the disease and not just the lesions,” J. Alzheimers Dis. 37(3), 469–474 (2013). 10.3233/JAD-130827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demetrius L. A., Magistretti P. J., Pellerin L., “Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid hypothesis and the Inverse Warburg effect,” Front. Physiol. 5, 522 (2015). 10.3389/fphys.2014.00522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy M. P., LeVine H., 3rd, “Alzheimer’s disease and the amyloid-β peptide,” J. Alzheimers Dis. 19(1), 311–323 (2010). 10.3233/JAD-2010-1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunkel P., Chai C. L., Sperlágh B., Huleatt P. B., Mátyus P., “Clinical utility of neuroprotective agents in neurodegenerative diseases: current status of drug development for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,” Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 21(9), 1267–1308 (2012). 10.1517/13543784.2012.703178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biogen/Eisai Halt Phase 3 Aducanumab Trials. https://www.alzforum.org/news/research-news/biogeneisai-halt-phase-3-aducanumab-trials

- 16.Da Mesquita S., Louveau A., Vaccari A., Smirnov I., Cornelison R. C., Kingsmore K. M., Contarino C., Onengut-Gumuscu S., Farber E., Raper D., Viar K. E., Powell R. D., Baker W., Dabhi N., Bai R., Cao R., Hu S., Rich S. S., Munson J. M., Lopes M. B., Overall C. C., Acton S. T., Kipnis J., “Functional aspects of meningeal lymphatics in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease,” Nature 560(7717), 185–191 (2018). 10.1038/s41586-018-0368-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hennessy M., Hamblin M. R., “Photobiomodulation and the brain: a new paradigm,” J. Optics 19(1), 013–003 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson T. A., Morries L. D., “Near-infrared photonic energy penetration: can infrared phototherapy effectively reach the Human brain?” Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 11(1), 2191–2208 (2015). 10.2147/NDT.S78182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang J., Ren Y., Wang R., Li C., Wang Y., Chu X., “Transcranial Low-Level Laser Therapy for Depression and Alzheimer’s Disease,” Neuropsychiatry (London) 8(2), 477–483 (2018). 10.4172/Neuropsychiatry.1000369 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamblin M. R., “Photobiomodulation for traumatic brain injury and stroke,” J. Neurosci. Res. 96(4), 731–743 (2018). 10.1002/jnr.24190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salehpour F., Mahmoudi J., Kamari F., Sadigh-Eteghad S., Rasta S. H., Hamblin M. R., “Brain Photobiomodulation Therapy: a Narrative Review,” Mol. Neurobiol. 55(8), 6601–6636 (2018), doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0852-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cassano P., Cusin C., Mischoulon D., Hamblin M. R., De Taboada L., Pisoni A., Chang T., Yeung A., Ionescu D. F., Petrie S. R., Nierenberg A. A., Fava M., Iosifescu D. V., “Near-Infrared Transcranial Radiation for Major Depressive Disorder: Proof of Concept Study,” Psychiatry J. 2015, 352979 (2015). 10.1155/2015/352979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de la Torre J. C., “Treating cognitive impairment with transcranial low level laser therapy,” J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 168(1), 149–155 (2017). 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naeser M. A., Hamblin M. R., “Potential for transcranial laser or LED therapy to treat stroke, traumatic brain injury, and neurodegenerative disease,” Photomed. Laser Surg. 29(7), 443–446 (2011). 10.1089/pho.2011.9908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cassano P., Petrie S. R., Hamblin M. R., Henderson T. A., Iosifescu D. V., “Review of transcranial photobiomodulation for major depressive disorder: targeting brain metabolism, inflammation, oxidative stress, and neurogenesis,” Neurophotonics 3(3), 031404 (2016). 10.1117/1.NPh.3.3.031404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Y., Wang R., Dong Y., Tucker D., Zhao N., Ahmed M. E., Zhu L., Liu T. C., Cohen R. M., Zhang Q., Zhang Q., “Low-level laser therapy for beta amyloid toxicity in rat hippocampus,” Neurobiol. Aging 49(1), 165–182 (2017). 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grillo S. L., Duggett N. A., Ennaceur A., Chazot P. L., “Non-invasive infra-red therapy (1072 nm) reduces β-amyloid protein levels in the brain of an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model, TASTPM,” J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 123(1), 13–22 (2013). 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2013.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michalikova S., Ennaceur A., van Rensburg R., Chazot P. L., “Emotional responses and memory performance of middle-aged CD1 mice in a 3D maze: effects of low infrared light,” Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 89(4), 480–488 (2008). 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang L., Xing D., Zhu D., Chen Q., “Low-power laser irradiation inhibiting Abeta25-35-induced PC12 cell apoptosis via PKC activation,” Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 22(1-4), 215–222 (2008). 10.1159/000149799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sokolovski S. G., Zolotovskaya S. A., Goltsov A., Pourreyron C., South A. P., Rafailov E. U., “Infrared laser pulse triggers increased singlet oxygen production in tumour cells,” Sci. Rep. 3(1), 3484 (2013), doi: 10.1038/srep03484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Facchinetti R., Bronzuoli M. R., Scuderi C., “An Animal Model of Alzheimer Disease Based on the Intrahippocampal Injection of Amyloid β-Peptide,” Methods Mol. Biol. 1727, 343–352 (2018). 10.1007/978-1-4939-7571-6_25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kowall N. W., Beal M. F., Busciglio J., Duffy L. K., Yankner B. A., “An in vivo model for the neurodegenerative effects of beta amyloid and protection by substance P,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88(16), 7247–7251 (1991). 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geng Y., Li C., Liu J., Xing G., Zhou L., Dong M., Li X., Niu Y., “Beta-Asarone Improves Cognitive Function by Suppressing Neuronal Apoptosis in the Beta-Amyloid Hippocampus Injection Rats,” Biol. Pharm. Bull. 33(5), 836–843 (2010). 10.1248/bpb.33.836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown R. E., Corey S. C., Moore A. K., “Differences in measures of exploration and fear in MHC-congenic C57BL/6J and B6-H-2K mice,” Behav. Genet. 26(4), 263–271 (1999). 10.1023/A:1021694307672 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flierl M. A., Stahel P. F., Beauchamp K. M., Morgan S. J., Smith W. R., Shohami E., “Mouse closed head injury model induced by a weight-drop device,” Nat. Protoc. 4(9), 1328–1337 (2009). 10.1038/nprot.2009.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lueptow L. M., “Novel Object Recognition Test for the Investigation of Learning and Memory in Mice,” J. Vis. Exp. 126(126), 55718 (2017). 10.3791/55718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Serrano-Pozo A., Frosch M. P., Masliah E., Hyman B. T., “Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease,” Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 1(1), a006189 (2011). 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kocahan S., Doğan Z., “Mechanisms of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis and Prevention: The Brain, Neural Pathology, N-methyl-D-aspartate Receptors, Tau Protein and Other Risk Factors,” Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 15(1), 1–8 (2017). 10.9758/cpn.2017.15.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Taboada L., Yu J., El-Amouri S., Gattoni-Celli S., Richieri S., McCarthy T., Streeter J., Kindy M. S., “Transcranial laser therapy attenuates amyloid-β peptide neuropathology in amyloid-β protein precursor transgenic mice,” J. Alzheimers Dis. 23(3), 521–535 (2011). 10.3233/JAD-2010-100894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Purushothuman S., Johnstone D. M., Nandasena C., Eersel J., Ittner L. M., Mitrofanis J., Stone J., “Near infrared light mitigates cerebellar pathology in transgenic mouse models of dementia,” Neurosci. Lett. 591(1), 155–159 (2015). 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.da Luz Eltchechem C., Salgado A. S. I., Zângaro R. A., da Silva Pereira M. C., Kerppers I. I., da Silva L. A., Parreira R. B., “Transcranial LED therapy on amyloid-β toxin 25-35 in the hippocampal region of rats,” Lasers Med. Sci. 32(4), 749–756 (2017). 10.1007/s10103-017-2156-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oron A., Oron U., “Low-level laser therapy to the bone marrow ameliorates neurodegenerative disease progression in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: a minireview,” Photomed. Laser Surg. 34(12), 627–630 (2016). 10.1089/pho.2015.4072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farfara D., Tuby H., Trudler D., Doron-Mandel E., Maltz L., Vassar R. J., Frenkel D., Oron U., “Low-level laser therapy ameliorates disease progression in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease,” J. Mol. Neurosci. 55(2), 430–436 (2015). 10.1007/s12031-014-0354-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang J., Liu L., Xing D., “Photobiomodulation by low-power laser irradiation attenuates Aβ-induced cell apoptosis through the Akt/GSK3β/β-catenin pathway,” Free Radic. Biol. Med. 53(7), 1459–1467 (2012). 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sommer A. P., Bieschke J., Friedrich R. P., Zhu D., Wanker E. E., Fecht H. J., Mereles D., Hunstein W., “670 nm laser light and EGCG complementarily reduce amyloid-β aggregates in human neuroblastoma cells: basis for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease?” Photomed. Laser Surg. 30(1), 54–60 (2012). 10.1089/pho.2011.3073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang H., Wu S., Xing D., “Inhibition of Aβ(25-35)-induced cell apoptosis by low-power-laser-irradiation (LPLI) through promoting Akt-dependent YAP cytoplasmic translocation,” Cell. Signal. 24(1), 224–232 (2012). 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu Z., Guo X., Yang Y., Tucker D., Lu Y., Xin N., Zhang G., Yang L., Li J., Du X., Zhang Q., Xu X., “Low-level laser irradiation improves depression-like behaviors in mice,” Mol. Neurobiol. 54(6), 4551–4559 (2017). 10.1007/s12035-016-9983-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mohammed H. S., “Transcranial low-level infrared laser irradiation ameliorates depression induced by reserpine in rats,” Lasers Med. Sci. 31(8), 1651–1656 (2016). 10.1007/s10103-016-2033-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Purushothuman S., Nandasena C., Johnstone D. M., Stone J., Mitrofanis J., “The impact of near-infrared light on dopaminergic cell survival in a transgenic mouse model of Parkinsonism,” Brain Res. 1535(1), 61–70 (2013). 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.08.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huisa B. N., Stemer A. B., Walker M. G., Rapp K., Meyer B. C., Zivin J. A., “Transcranial laser therapy for acute ischemic stroke: a pooled analysis of NEST-1 and NEST-2,” Int. J. Stroke 8(5), 315–320 (2013). 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00754.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lapchak P. A., Boitano P. D., “Transcranialnearinfrared laser therapy for stroke: how to recover from futility in the NEST-3 Clinical Trial,” Acta Neurochir. Suppl. (Wien) 121(1), 7–12 (2016). 10.1007/978-3-319-18497-5_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xuan W., Huang L., Hamblin M. R., “Repeated transcranial low-level laser therapy for traumatic brain injury in mice: biphasic dose response and long-term treatment outcome,” J. Biophotonics 9(11-12), 1263–1272 (2016). 10.1002/jbio.201500336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morries L. D., Cassano P., Henderson T. A., “Treatments for traumatic brain injury with emphasis on transcranial near-infrared laser phototherapy,” Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 11(1), 2159–2175 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Semyachkina-Glushkovskaya O. V., Sokolovski S. G., Goltsov A., Gekaluyk A. S., Bragina O. A., Saranceva E. I., Tuchin V. V., Rafailov E. U., “Laser-induced generation of singlet oxygen and its role in the cerebrovascular physiology,” Prog. Quantum Electron. 55, 112–128 (2017). 10.1016/j.pquantelec.2017.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Golovynskyi S., Golovynska I., Stepanova L. I., Datsenko O. I., Liu L., Qu J., Ohulchanskyy T. Y., “Optical windows for head tissues in near-infrared and short-wave infrared regions: Approaching transcranial light applications,” J. Biophotonics 11(12), e201800141 (2018). 10.1002/jbio.201800141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patel N., Pera P., Joshi P., Dukh M., Tabaczynski W. A., Siters K. E., Kryman M., Cheruku R. R., Durrani F., Missert J. R., Watson R., Ohulchanskyy T. Y., Tracy E. C., Baumann H., Pandey R. K., “Highly effective dual-function near-infrared (NIR) photosensitizer for fluorescence imaging and photodynamic therapy (PDT) of cancer,” J. Med. Chem. 59(21), 9774–9787 (2016), doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chakraborty S., Davis M. J., Muthuchamy M., “Emerging trends in the pathophysiology of lymphatic contractile function,” Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 38, 55–66 (2015). 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mitchell U. H., Mack G. L., “Low-level laser treatment with near-infrared light increases venous nitric oxide levels acutely: a single-blind, randomized clinical trial of efficacy,” Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 92(2), 151–156 (2013). 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318269d70a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lohr N. L., Keszler A., Pratt P., Bienengraber M., Warltier D. C., Hogg N., “Enhancement of nitric oxide release from nitrosyl hemoglobin and nitrosyl myoglobin by red/near infrared radiation: potential role in cardioprotection,” J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 47(2), 256–263 (2009). 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meneguzzo D. T., Lopes L. A., Pallota R., Soares-Ferreira L., Lopes-Martins R. A., Ribeiro M. S., “Prevention and treatment of mice paw edema by near-infrared low-level laser therapy on lymph nodes,” Lasers Med. Sci. 28(3), 973–980 (2013). 10.1007/s10103-012-1163-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Omar M. T., Shaheen A. A., Zafar H., “A systematic review of the effect of low-level laser therapy in the management of breast cancer-related lymphedema,” Support. Care Cancer 20(11), 2977–2984 (2012). 10.1007/s00520-012-1546-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smoot B., Chiavola-Larson L., Lee J., Manibusan H., Allen D. D., “Effect of low-level laser therapy on pain and swelling in women with breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” J. Cancer Surviv. 9(2), 287–304 (2015). 10.1007/s11764-014-0411-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Benedicenti S., Pepe I. M., Angiero F., Benedicenti A., “Intracellular ATP level increases in lymphocytes irradiated with infrared laser light of wavelength 904 nm,” Photomed. Laser Surg. 26(5), 451–453 (2008). 10.1089/pho.2007.2218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Semyachkina-Glushkovskaya O., Chehonin V., Borisova E., Fedosov I., Namykin A., Abdurashitov A., Shirokov A., Khlebtsov B., Lyubun Y., Navolokin N., Ulanova M., Shushunova N., Khorovodov A., Agranovich I., Bodrova A., Sagatova M., Shareef A. E., Saranceva E., Iskra T., Dvoryatkina M., Zhinchenko E., Sindeeva O., Tuchin V., Kurths J., “Photodynamic opening of the blood-brain barrier and pathways of brain clearing,” J. Biophotonics 11(8), e201700287 (2018). 10.1002/jbio.201700287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Semyachkina-Glushkovskaya O., Abdurashitov A., Dubrovsky A., Bragin D., Bragina O., Shushunova N., Maslyakova G., Navolokin N., Bucharskaya A., Tuchin V., Kurths J., Shirokov A., “Application of optical coherence tomography for in vivo monitoring of the meningeal lymphatic vessels during opening of blood-brain barrier: mechanisms of brain clearing,” J. Biomed. Opt. 22(12), 1–9 (2017). 10.1117/1.JBO.22.12.121719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Semyachkina-Glushkovskaya O., Postnov D., Kurths J., “Blood−Brain Barrier, Lymphatic Clearance, and Recovery: Ariadne’s Thread in Labyrinths of Hypotheses,” Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19(12), 3818 (2018). 10.3390/ijms19123818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]