Abstract

Objective

A rapid molecular diagnostic test (RMDT) offers a fast and accurate detection of respiratory viruses, but its impact on the timeliness of care in the emergency department (ED) may depend on the timing of the test. The aim of the study was to determine if the timing of respiratory virus testing using a RMDT in the ED had an association with patient care outcomes.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Setting

Linked ED and laboratory data from six EDs in New South Wales, Australia.

Participants

Adult patients presenting to EDs during the 2017 influenza season and tested for respiratory viruses using a RMDT. The timing of respiratory virus testing was defined as the time from a patient’s ED arrival to time of sample receipt at the hospital laboratory.

Outcome measures

ED length of stay (LOS), >4 hour ED LOS and having a pending RMDT result at ED disposition.

Results

A total of 2168 patients were included. The median timing of respiratory virus testing was 224 min (IQR, 133–349). Every 30 min increase in the timing of respiratory virus testing was associated with a 24.0 min increase in the median ED LOS (95% CI, 21.8–26.1; p<0.001), a 51% increase in the likelihood of staying >4 hours in ED (OR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.41 to 1.63; p<0.001) and a 4% increase in the likelihood of having a pending RMDT result at ED disposition (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.05; p<0.001) after adjustment for confounders.

Conclusion

The timing of respiratory virus molecular testing in EDs was significantly associated with a range of outcome indicators. Results suggest the potential to maximise the benefits of RMDT by introducing an early diagnostic protocol such as triage-initiated testing.

Keywords: diagnostic microbiology, infection control, molecular diagnostics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to investigate the relationship between the timing of respiratory virus molecular testing and outcomes of patients presenting to emergency department with respiratory infections.

This is a large multicentre study that involved six hospitals, enhancing the generalisability of our findings.

Our findings may not be applicable to paediatric populations as this study did not include patients aged ≤18 years.

Being an observational study, our findings do not imply a causal relationship.

Our analyses were not adjusted for other relevant factors (eg, access block) which may have confounded the findings of this study.

Introduction

The accurate diagnosis of the cause of respiratory infections has over recent years depended on a molecular method using a multiplex PCR panel testing. Multiplex PCR provides accurate diagnoses, but has been traditionally performed in a central laboratory with a lengthy test turnaround time (TAT), and with major repercussions for the efficiency of emergency department (ED) workflows and care processes.

ED overcrowding has been recognised as a growing problem in Australia and worldwide, contributing to deficits in the performance of the health system.1–3 Delay in laboratory test results is often considered as one of many factors contributing to ED overcrowding and prolonged ED length of stay (LOS).4–6 Fast result availability through the use of rapid diagnostic tests can potentially improve patient flow and lessen the burden of ED overcrowding.7 8 Optimising patient flow is of particular importance given the 4 hour ED LOS target introduced in Australia in 2011 to improve the quality and timeliness of care across EDs.9

Diagnostic kits for the rapid diagnosis of respiratory viruses using a molecular PCR-based technology are now available for use in hospital-based laboratories. Existing evidence shows that rapid molecular diagnostic test (RMDT) in ED is associated with a significant decrease in hospital admissions,8 10 shorter TAT8 and reductions in hospital resource utilisation.11–13 However, evidence of the association between RMDT and ED LOS have been inconsistent.8 14 15 Our previous study did not detect a significant association between RMDT use and ED LOS.16 We hypothesised that this may be due to the fact that RMDT ordering took place a median of 3 hours after a patient’s ED arrival16 suggesting that the impact of RMDT on ED LOS and other timeliness of care processes may depend on the timing of the test.

The aim of the study was to determine if the timing of respiratory virus testing using RMDT in ED is associated with indicators related to timeliness of patient care including ED LOS, meeting the 4-hour ED LOS Australian emergency access target; having a pending RMDT result at ED disposition.

Method

Setting

A retrospective observational study was conducted across six public hospitals in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. All study sites provide 24 hours EDs: three principal referral hospitals (EDs A, B and D) with 76 228, 54 443 and 61 348 annual ED presentations, respectively, two acute group A hospitals (ED C and ED F) with 50 025 and 38 039 annual ED presentations, respectively, and one public acute group A hospital (ED E) with 29 479 annual ED presentations (2016 data).17

Population

The study period was the 2017 influenza season, between 1 July and 31 October. The inclusion criteria were patients presenting to EDs with symptoms of respiratory infection and aged ≥18 years; Australasian triage scale categories of 3 (potentially life-threatening), 4 (potentially serious) or 5 (less urgent) and tested for respiratory viruses at a hospital-based laboratory using a RMDT. The RMDT used in this study was a Cepheid Xpert Flu/Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) XC (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California, USA).16 18 The Cepheid Xpert Flu/RSV XC assay demonstrated a high sensitivity and specificity for rapid detection of influenza A, influenza B and RSV.19

Patients with triage categories of 1 (immediately life-threatening) or 2 (imminently life-threatening) were excluded from the current analysis as patients required urgent medical assessment and treatment. Relevant patient presentation characteristics and laboratory test data were obtained by linking the ED and laboratory information system datasets.6

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was ED LOS. ED LOS was defined as the length of time between ED arrival and patient disposition. The secondary outcomes included >4-hour ED LOS and having a pending RMDT result at ED disposition. A pending test result was defined as the unavailability of a verified RMDT result at the time of patient disposition from the ED.20

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including medians with IQR were reported. The RMDT TAT was defined as the time of sample receipt at the hospital laboratory to time of availability of RMDT result. The exploratory variable was the timing of respiratory virus testing using a RMDT, defined as the time from a patient’s ED arrival to time of sample receipt at the hospital laboratory. For result interpretation purposes, the relationship between the timing of the RMDT and study outcomes were estimated for every 30 min increase in the timing of the test.

The association between the timing of the RMDT and ED LOS was assessed using a median regression. As the ED LOS data were highly skewed, a commonly used approach such as ordinary least squares regression which models the conditional mean of the outcome variable was not appropriate methods.21 Median regression is a special type of quantile regression which estimates the median of the outcome variable conditional on the values of the predictor variables.22 It is robust to extreme values and therefore well suited for modelling such data.23

Binary logistic regression was used to assess the association between the timing of the RMDT and the secondary outcomes (eg, >4-hour ED LOS, yes/no). The strength of the associations was measured using OR with a 95% CI.

For all outcomes, the findings were reported for the overall sample and by study ED. Subgroup analyses by patient disposition and ED arrival time were also conducted. The baseline covariates included age, gender, triage category, arrival time, arrival day of week, mode of arrival, patient disposition, overall number of tests ordered and number of test order episodes (tests ordered at one point in time during the ED stay). All analyses were adjusted for potential confounders—any variable having a significant association with a given outcome in a univariate analysis (p<0.05) was selected for the multivariate model. P values were two-tailed and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using Stata V.15 (StataCorp LP).

Patient and public involvement

This study was conducted without patient and public involvement as it was a retrospective study conducted using pre-existing administrative data. The patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 2168 patients were included in the study. Table 1 presents baseline characteristics. The median patient age was 74 years and 55.2% (n=1196) were female (table 1). Overall, there were 16 321 pathology tests ordered (ie, RMDT and other tests combined) with medians of three test order episodes during the ED stay and seven tests per patient. Analysis of RMDT results showed that 28.9% (n=626) were positive for either influenza A/B (n=617) or RSV (n=9). No patients tested positive for both influenza and RSV. The overall median TAT of RMDT was 183 min but this ranged from 104 min at ED A to 622 min at ED F.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variables | Result (n=2168) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 972 (44.8) |

| Female | 1196 (55.2) |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 74 (56–84) |

| Triage scale, n (%) | |

| Category 3 | 1777 (82.0) |

| Category 4/5 | 391 (18.0) |

| Arrival time, n (%) | |

| 0700 hours to 1900 hours | 1528 (70.5) |

| 1900 hours to 0700 hours | 640 (29.5) |

| Arrival day of week, n (%) | |

| Monday | 356 (16.4) |

| Tuesday | 294 (13.6) |

| Wednesday | 327 (15.1) |

| Thursday | 300 (13.8) |

| Friday | 308 (14.2) |

| Saturday | 257 (11.9) |

| Sunday | 326 (15.0) |

| Mode of arrival, n (%) | |

| Private/public transport | 906 (41.8) |

| State ambulance* | 1262 (58.2) |

| Study ED, n (%) | |

| A | 723 (33.4) |

| B | 193 (8.9) |

| C | 301 (13.9) |

| D | 530 (24.5) |

| E | 239 (11.0) |

| F | 182 (8.4) |

| Patient disposition, n (%) | |

| Admitted | 1567 (72.3) |

| Discharged | 545 (25.1) |

| Other† | 56 (2.6) |

| Test order episode, median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) |

| Overall tests ordered, median (IQR) | 7 (5–9) |

| Test result, n (%) | |

| Positive | 626 (28.9) |

| Negative | 1542 (71.1) |

*Fifteen patients arriving by either wheelchair, correctional services vehicle, helicopter rescue service or walked-in were combined with ‘State ambulance’.

†Transferred to another hospital or left ED at own risk.

ED, emergency department.

Timing of respiratory virus testing

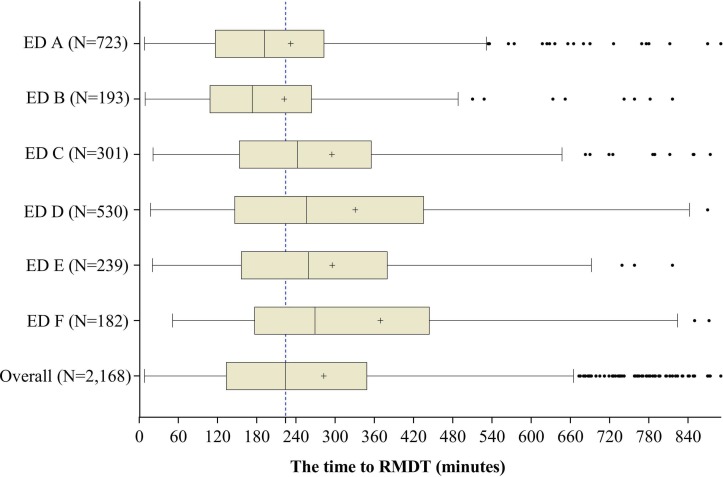

The median time from ED presentation to respiratory virus testing using the RMDT for all samples was 224 min (IQR, 133–349). There was considerable variation in the median time to RMDT across EDs which ranged from 173 min (IQR, 108–264) at ED B to 269 min (IQR, 178–444) at ED F (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The time to RMDT by study EDs: boxes represent the IQR (25th and 75th percentiles) with the median (50th percentile) value within the boxes, the mean value is represented as a ‘+’ and the capped bars represent the 10th and 90th percentiles. The broken line indicates the overall median time to RMDT.

Study outcomes

The overall median ED LOS was 533 min. ED B had the shortest and ED D had the longest median ED LOS. Overall, 88% (n=1907) of patients stayed >4 hours in ED (range across EDs: 78.2% at ED B to 92.0% at ED A). RMDT results were pending for 38% (n=824) of patients at the time of ED disposition (range across EDs: 15.1% at ED A to 70.7% at ED E) (table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of study outcomes

| ED | N | Primary outcome | Secondary outcomes | |

| ED LOS (minute), Median (IQR) | >4-hour ED LOS, N (%) | Patient with a pending RMDT result, N (%) | ||

| A | 723 | 545 (358–953) | 665 (92.0) | 109 (15.1) |

| B | 193 | 376 (257–549) | 151 (78.2) | 80 (41.5) |

| C | 301 | 490 (342–859) | 263 (87.4) | 157 (52.2) |

| D | 530 | 714 (366–1172) | 457 (86.2) | 186 (35.1) |

| E | 239 | 455 (336–657) | 208 (87.0) | 169 (70.7) |

| F | 182 | 700 (389–1177) | 163 (89.6) | 123 (67.6) |

| Overall | 2168 | 533 (338.5–975) | 1907 (88.0) | 824 (38.0) |

ED, Emergency Department; LOS, Length of Stay.

Association between the timing of respiratory virus testing and primary outcome

The results of univariate analysis describing the association between baseline characteristics and each study outcome are presented in online supplementary table 1. All baseline variables except arrival day of week and test result were significantly associated with ED LOS (online table S1).

bmjopen-2019-030104supp001.pdf (85.9KB, pdf)

The timing of respiratory virus testing was strongly associated with ED LOS. After adjustment for potential confounders, every 30 min increase in the time to RMDT was associated with a 24.0 min increase in the median ED LOS (95% CI, 21.8 to 26.1; p<0.001). There were no major differences, in this association, by ED (table 3).

Table 3.

Median regression showing association between the timing of respiratory virus testing (every 30 min increase) and ED LOS (minutes)

| ED | N | Unadjusted | Adjusted* |

| Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | ||

| A | 723 | 26.4 (22.2 to 30.5) | 21.6 (16.5 to 26.7) |

| B | 193 | 32.4 (27.1 to 37.7) | 26.4 (20.0 to 32.8) |

| C | 301 | 30.9 (26.4 to 35.4) | 26.7 (22.3 to 31.2) |

| D | 530 | 31.7 (26.1 to 37.3) | 21.7 (17.7 to 25.8) |

| E | 239 | 25.8 (21.0 to 30.7) | 26.3 (21.5 to 31.0) |

| F | 182 | 28.0 (19.8 to 36.1) | 23.2 (14.6 to 31.8) |

| Overall | 2168 | 29.4 (27.5 to 31.2) | 24.0 (21.8 to 26.1) |

All analyses were highly significant with a p value of <0.001. The coefficient indicates the median change in a given outcome (eg, ED LOS) for every 30 min increase in the timing of the RMDT.

*Adjusted for gender, age, triage category, ED arrival time, mode of arrival, study ED, patient disposition, test order episode.

ED, emergency department; LOS, length of stay.

A subgroup analysis by patient disposition and ED arrival time is shown in online supplementary table 2. The association was more pronounced among patients who were subsequently discharged than for admitted patients and among patients who arrived to EDs between 0700 hours to 1900 hours than for patients arriving between 1900 hours to 0700 hours (online table S2).

Association between the timing of respiratory virus testing and secondary outcomes

The median time to RMDT was 113 min (IQR, 76–152) for patients with ≤4 hours ED LOS (n=261) and 250 min (IQR, 153–370) for patients staying >4 hours in ED (n=1907). The median time to RMDT was 211 min (IQR, 122–336) for patients who received RMDT results before disposition (n=1344) and 247 min (IQR, 151–364) for patients with pending RMDT results at disposition (n=824). Of the patients with pending RMDT results, the results of 30.3% (n=250) eventually came back positive for either influenza A/B or RSV.

The results of binary logistic regression are presented in table 4 and show associations between the time to RMDT and secondary outcomes. The time to RMDT was positively associated with both secondary outcomes. In the adjusted model, for every 30 min increase in time to RMDT, the likelihood of staying >4 hours in ED (versus having ≤4 hours ED LOS) increased by a factor of 1.51 (OR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.41 to 1.63; p<0.001). This is equivalent to a 51% increase in the likelihood of staying >4 hours in ED.

Table 4.

Binary logistic regression showing association between the timing of respiratory virus testing (every 30 min increase) and secondary outcomes

| ED | N | >4 hour ED LOS | Patient with a pending RMDT result | ||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | ||

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| A | 723 | 1.58 (1.37 to 1.82) | 1.51 (1.28 to 1.79) | 1.04 (1.01 to 1.07) | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.10) |

| B | 193 | 1.74 (1.41 to 2.14) | 1.70 (1.34 to 2.17) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.12) | 1.16 (1.07 to 1.25) |

| C | 301 | 1.51 (1.29 to 1.76) | 1.48 (1.25 to 1.75) | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.02)NS | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.06)NS |

| D | 530 | 1.69 (1.48 to 1.93) | 1.64 (1.41 to 1.90) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.01)NS | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.05)NS |

| E | 239 | 1.40 (1.21 to 1.61) | 1.39 (1.19 to 1.63) | 1.00 (0.96 to 1.04)NS | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.07)NS |

| F | 182 | 1.63 (1.28 to 2.07) | 1.90 (1.24 to 2.91) | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.05)NS | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.09) |

| Overall | 2168 | 1.54 (1.45 to 1.64) | 1.51 (1.41 to 1.63) | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03) | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.05) |

All analyses, except those marked ‘NS’, were significant with a p value of <0.05. The coefficient indicates the likelihood of a given outcome for every 30 min increase in the timing of the RMDT.

*Adjusted for age, triage category, mode of arrival, study ED, patient disposition, test order episode and test result.

†Adjusted for gender, age, triage category, mode of arrival, study ED, patient disposition, test order episode.

ED, emergency department; LOS, length of stay; NS, not significant, RMDT, rapid molecular diagnostic test.

The association between the timing of the RMDT and having a pending test result at ED disposition was not as striking as with other outcomes. In the total sample, for every 30 min increase in the time to RMDT, the likelihood of experiencing a pending RMDT result at ED disposition increased by a factor of 1.04—a 4% increase—(OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.05; p<0.001) after adjustment for potential confounders. When the analysis was conducted separately by study EDs, the association was not statistically significant for EDs C, D and E (table 4).

Discussion

Key findings

The major finding of this study is that for every 30 min increase in the time from ED arrival until respiratory virus testing there was a 24.0 min increase in the median ED LOS. Moreover, an increase in the timing of respiratory virus testing was associated with a greater likelihood of experiencing an ED LOS greater than 4 hours and having a pending RMDT result at the time of disposition from the ED.

Interpretation and comparison with existing literature

Previous studies have also reported a significant association between ED LOS and the time taken to obtain the results from laboratory testing in EDs.6 24–26 However, unlike our study, the previous studies have been conducted in a context of broader patient populations visiting ED and, therefore, direct comparisons with other studies are not possible. For example, Li et al conducted a retrospective study that included 123 455 ED presentations for all conditions across four EDs in NSW, Australia. That study assessed the relationship between ED LOS and TAT and found a 17 min increase in ED LOS for each 30 min increase in TAT.6 In a recent large US study, Kaushik et al evaluated the impact of reducing laboratory TAT on ED LOS using data from 486 hospitals with 4 483 169 ED presentations.25 In that study, a 1 min decrease in TAT was associated with a 0.50 min decrease in ED LOS.25 In another US study, Kocher et al investigated the effect of diagnostic testing and treatment patterns on ED LOS using data from a large national study that included approximately 360 million ED presentations.26 They found that, the ordering of a blood test was the most time consuming testing modality resulting in an adjusted marginal effect of a 72 min increase in ED LOS and the likelihood of experiencing a >4-hour ED LOS increased by a factor of 2.29.26

The present study revealed a direct relationship between the timing of respiratory virus testing and a range of indicators of timeliness of patient care in ED. Delays in the ordering of RMDT had a negative impact on our selected ED outcomes. Our results suggest that earlier initiation of RMDT may result in reduced ED LOS. More systemic or procedural changes in the way healthcare is delivered (eg, introduction of an early diagnostic testing protocol such as a triage-initiated testing) may be needed in order to maximise its benefits. Triage-based testing protocols have been shown to reduce wait times and ED LOS, decrease costs, reduces time to receiving medications and improve patient satisfaction in other conditions.27–29 In a randomised controlled trial conducted in the USA that includes more than 1000 ED patients aged <3 years, influenza testing at triage using a non-molecular antigen-based method led to significantly shorter ED LOS.30 Future research should assess the potential impact of triage-initiated ordering of RMDT for patients presenting to ED with suspected respiratory viral infection on patient outcomes including the effect on ED LOS.

Implications of the study

The current study showed that a delay in respiratory virus testing was associated with an increased likelihood of having a pending test result at ED disposition. The test results of 30.3% of patients with pending test results eventually came back positive for either influenza A/B or RSV. This finding has significant patient safety implications. Pending test results at discharge are less likely to be followed-up and may lead to missed or delayed diagnosis and increased hospital representations.31 32 From an infection transmission perspective, patients who were discharged with pending results could potentially spread the infection, especially if appropriate management was not provided.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Our study has some strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the relationship between the timing of respiratory virus molecular testing and ED outcomes among patients presenting with respiratory infections. Another strength of the study was that it is a multicentre study that involved six hospitals with a large sample size, enhancing the external validity (generalizability) of our findings.

The findings of the current study should be interpreted in the context of the following methodological limitations. First, this study was conducted among adult patients (age >18 years). Given the impact of RMDT on ED LOS can be different among patients aged ≤18 years,33 our findings may not be applicable to paediatric populations. Second, being an observational study, the findings of the current study do not imply a causal relationship. Thirdly, our analyses were not adjusted for other factors which may have confounded the findings of this study. The input-throughput-output model34 is commonly used in studies assessing factors affecting LOS and ED overcrowding.26 35 36 Input factors are characteristics that contribute to the demand for ED services (eg, patient demographics and ED presentation characteristics).34 Throughput factors are characteristics related to ED care such as diagnostic evaluations and treatment.26 34 Output factors are organisational or hospital capacity-related characteristics (eg, access block).34 36 While our multivariable models were adjusted for a number of input variables, our current analysis did not consider the effect of several throughput and output/organisational factors due to lack of data. Previous studies have shown that throughput factors such as diagnostic imaging,26 clinical assessment37 and treatment (administering a medication or performing a procedure)26 and output/organisational factors36 38 39 are important factors influencing ED LOS. Finally, the current study did not consider the appropriateness of RMDT ordering practices. Reducing inappropriate or unnecessary respiratory virus testing could also have a considerable impact on reducing ED LOS.

Conclusion

The timing of respiratory virus molecular testing in EDs was significantly associated with a range of outcome indicators. Results suggest the potential to maximise the benefits of RMDT by introducing an early diagnostic protocol such as a triage-initiated testing which warrants investigations in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AG, LL, MRD, RL, JT and JW conceived the study and obtained research funding. NW, LL, MRD, RL, RY, KC, JT, WV, JW and AG have made substantial contributions to the design of the study. NW and LL conducted data extraction, cleaning, linkage and analysis. NW, LL, MRD, RL, KC, JT, JW and AG involved in the interpretation of the results with input from RY and WV. NW, LL, MRD, JT and AG contributed to the drafting of the manuscript with input from RL, RY, KC and WV. All authors involved in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content as well as approved the final version to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Partnership Project Grant [grant number, APP1111925].

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the South Eastern Sydney Local Health District (HREC/16/POWH/412).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Wickman L, Svensson P, Djärv T. Effect of crowding on length of stay for common chief complaints in the emergency department: A STROBE cohort study. Medicine 2017;96:e8457 10.1097/MD.0000000000008457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sikka R, Mehta S, Kaucky C, et al. ED crowding is associated with an increased time to pneumonia treatment. Am J Emerg Med 2010;28:809–12. 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morley C, Unwin M, Peterson GM, et al. Emergency department crowding: a systematic review of causes, consequences and solutions. PLoS One 2018;13:e0203316 10.1371/journal.pone.0203316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lewandrowski K. POC testing in the emergency department: strategies to improve clinical and operational outcomes. Radiometer Medical ApS, 2700 Brønshøj, Denmark. 2011. https://acutecaretesting.org/-/media/acutecaretesting/files/pdf/poc-testing-in-the-emergency-department-strategies-to-improve-clinical-and-operational-outcomes.pdf (Accessed 30 Jan 2019).

- 5. Pines JM, Hilton JA, Weber EJ, et al. International perspectives on emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:1358–70. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li L, Georgiou A, Vecellio E, et al. The effect of laboratory testing on emergency department length of stay: a multihospital longitudinal study applying a cross-classified random-effect modeling approach. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22:38–46. 10.1111/acem.12565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rooney KD, Schilling UM. Point-of-care testing in the overcrowded emergency department--can it make a difference? Crit Care 2014;18:692 10.1186/s13054-014-0692-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rappo U, Schuetz AN, Jenkins SG, et al. Impact of early detection of respiratory viruses by multiplex PCR assay on clinical outcomes in adult patients. J Clin Microbiol 2016;54:2096–103. 10.1128/JCM.00549-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sullivan C, Staib A, Khanna S, et al. The National Emergency Access Target (NEAT) and the 4-hour rule: time to review the target. Med J Aust 2016;204:354 10.5694/mja15.01177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Linehan E, Brennan M, O’Rourke S, et al. Impact of introduction of xpert flu assay for influenza PCR testing on obstetric patients: a quality improvement project. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018;31:1016–20. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1306048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ko F, Drews SJ. The impact of commercial rapid respiratory virus diagnostic tests on patient outcomes and health system utilization. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2017;17:917–31. 10.1080/14737159.2017.1372195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Poehling KA, Zhu Y, Tang YW, et al. Accuracy and impact of a point-of-care rapid influenza test in young children with respiratory illnesses. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160:713–8. 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blaschke AJ, Shapiro DJ, Pavia AT, et al. A National Study of the Impact of Rapid Influenza Testing on Clinical Care in the Emergency Department. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2014;3:112–8. 10.1093/jpids/pit071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jeong HW, Heo JY, Park JS, et al. Effect of the influenza virus rapid antigen test on a physician’s decision to prescribe antibiotics and on patient length of stay in the emergency department. PLoS One 2014;9:e110978 10.1371/journal.pone.0110978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Doan Q, Enarson P, Kissoon N, et al. Rapid viral diagnosis for acute febrile respiratory illness in children in the Emergency Department. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;9:Cd006452 10.1002/14651858.CD006452.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wabe N, Li L, Lindeman R, et al. The impact of rapid molecular diagnostic testing for respiratory viruses on outcomes for emergency department patients. Med J Aust 2019;210:316–20. 10.5694/mja2.50049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dahm MR, Georgiou A, Westbrook JI, et al. Delivering safe and effective test-result communication, management and follow-up: a mixed-methods study protocol. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020235 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wabe N, Li L, Lindeman R, et al. Impact of rapid molecular diagnostic testing of respiratory viruses on outcomes of adults hospitalized with respiratory illness: a multicenter quasi-experimental study. J Clin Microbiol 2019;57:e01727–18. 10.1128/JCM.01727-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arbefeville S, Thonen-Kerr E, Ferrieri P. Prospective and retrospective evaluation of the performance of the FDA-Approved Cepheid Xpert Flu/RSV XC Assay. Lab Med 2017;48:e53–e56. 10.1093/labmed/lmx038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wabe N, Li L, Sezgin G, et al. Pending Laboratory Test Results at the Time of Discharge: A 3-Year Retrospective Comparison of Paper Versus Electronic Test Ordering in Three Emergency Departments. Stud Health Technol Inform 2018;252:164–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lê Cook B, Manning WG. Thinking beyond the mean: a practical guide for using quantile regression methods for health services research. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 2013;25:55–9. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2013.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McGreevy KM, Lipsitz SR, Linder JA, et al. Using median regression to obtain adjusted estimates of central tendency for skewed laboratory and epidemiologic data. Clin Chem 2009;55:165–9. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.106260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee AH, Fung WK, Fu B. Analyzing hospital length of stay: mean or median regression? Med Care 2003;41:681–6. 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062550.23101.6F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Holland LL, Smith LL, Blick KE. Reducing laboratory turnaround time outliers can reduce emergency department patient length of stay: an 11-hospital study. Am J Clin Pathol 2005;124:672–4. 10.1309/E9QPVQ6G2FBVMJ3B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaushik N, Khangulov VS, O’Hara M, O’Hara M, et al. Reduction in laboratory turnaround time decreases emergency room length of stay. Open Access Emerg Med 2018;10:37–45. 10.2147/OAEM.S155988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kocher KE, Meurer WJ, Desmond JS, et al. Effect of testing and treatment on emergency department length of stay using a national database. Acad Emerg Med 2012;19:525–34. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01353.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wiler JL, Gentle C, Halfpenny JM, et al. Optimizing emergency department front-end operations. Ann Emerg Med 2010;55:142–60. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oredsson S, Jonsson H, Rognes J, et al. A systematic review of triage-related interventions to improve patient flow in emergency departments. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2011;19:43 10.1186/1757-7241-19-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barksdale AN, Hackman JL, Williams K, et al. ED triage pain protocol reduces time to receiving analgesics in patients with painful conditions. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:2362–6. 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.08.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Abanses JC, Dowd MD, Simon SD, et al. Impact of rapid influenza testing at triage on management of febrile infants and young children. Pediatr Emerg Care 2006;22:145–9. 10.1097/01.pec.0000202454.19237.b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Callen J, Georgiou A, Li J, et al. The safety implications of missed test results for hospitalised patients: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:194–9. 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.044339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roy CL, Poon EG, Karson AS, et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:121–8. 10.7326/0003-4819-143-2-200507190-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wabe N, Li L, Lindeman R, et al. Association of rapid molecular diagnostic testing of respiratory viruses with emergency department patient and laboratory outcomes: a before-after study. Medical Journal of Australia 2018. (Accepted 12 Nov 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 34. Asplin BR, Magid DJ, Rhodes KV, et al. A conceptual model of emergency department crowding. Ann Emerg Med 2003;42:173–80. 10.1067/mem.2003.302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Doupe M, Chateau D, Derksen S, et al. Factors affecting emergency department waiting room times in Winnipeg: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, University of Manitoba, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bashkin O, Caspi S, Haligoa R, et al. Organizational factors affecting length of stay in the emergency department: initial observational study. Isr J Health Policy Res 2015;4:38 10.1186/s13584-015-0035-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yoon P, Steiner I, Reinhardt G. Analysis of factors influencing length of stay in the emergency department. CJEM 2003;5:155–61. 10.1017/S1481803500006539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Forero R, McCarthy S, Hillman K. Access block and emergency department overcrowding. Crit Care 2011;15:216 10.1186/cc9998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fatovich DM, Nagree Y, Sprivulis P. Access block causes emergency department overcrowding and ambulance diversion in Perth, Western Australia. Emerg Med J 2005;22:351–4. 10.1136/emj.2004.018002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030104supp001.pdf (85.9KB, pdf)