Abstract

Objective

In the setting of reperfused ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) contributes to reperfusion injury. Among ROS, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) showed toxic effects on human cardiomyocytes and may induce microcirculatory impairment. Glutathione (GSH) is a water-soluble tripeptide with a potent oxidant scavenging activity. We hypothesised that the infusion of GSH before acute reoxygenation might counteract the deleterious effects of increased H2O2 generation on myocardium.

Methods

Fifty consecutive patients with STEMI, scheduled to undergo primary angioplasty, were randomly assigned, before intervention, to receive an infusion of GSH (2500 mg/25 mL over 10 min), followed by drug administration at the same doses at 24, 48 and 72 hours elapsing time or placebo. Peripheral blood samples were obtained before and at the end of the procedure, as well as after 5 days. H2O2 production, 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) formation, H2O2 breakdown activity (HBA) and nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability were determined. Serum cardiactroponin T (cTpT) was measured at admission and up to 5 days.

Results

Following acute reperfusion, a significant reduction of H2O2 production (p=0.0015) and 8-iso-PGF2α levels (p=0.0003), as well as a significant increase in HBA (p<0.0001)and NO bioavailability (p=0.035), was found in the GSH group as compared with placebo. In treated patients, attenuated production of H2O2 persisted up to 5 days from the index procedure (p=0.009) and these changes was linked to those of the cTpT levels (r=0.41, p=0.023).

Conclusion

The prophylactic and prolonged infusion of GSH seems to determine a rapid onset and persistent blunting of H2O2 generation improving myocardial cell survival. Nevertheless, a larger trial, adequately powered for evaluation of clinical endpoints, is ongoing to confirm the current finding.

Trial registration number

EUDRACT 2014-00448625; Pre-results.

Keywords: glutathione:, STEMI, reperfusion injury, reactive oxygen species, hydrogen peroxide, percutaneous coronary interventions

Strengths and limitations of this study.

In patients who suffer from ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), acute reoxygenation of ischaemic myocardium can induce additional myocardial cell injury mainly driven by heightened oxidative status.

Reactive oxygen species generation further contributes to damage myocardium by limiting bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO) at microcirculatory level.

This pilot study demonstrates that in the setting of STEMI reperfusion, the rapid onset and prolonged antioxidant (scavenging) activity obtained by the infusion of glutathione (GSH) protects the myocardium.

This study is limited by the lack of clinical endpoints and the small sample size. Moreover, qualitative assessment of GSH-induced improvement of myocardial reperfusion indexes might only represent the effect of a preserved microcirculatory responsiveness to vasoactive substances (ie, NO) but unable to limit the expansion of myocardial cell damage.

Introduction

It is well known that reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced at an accelerated rate in tissues subjected to reperfusion and that the accumulation of ROS contributes to reperfusion injury during reintroduction of molecular oxygen to the ischaemic environment.1 2

In the setting of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), ROS-induced myocardial cell death occurs in the first few minutes of the acute reoxygenation3 and may continue for weeks to months by the activation of apoptosis and autophagy processes.4 5 ROS generation also contributes to structural capillary damage and endothelial dysfunction, which hinder the achievement of an optimal perfusion grade at microcirculatory level.6 7 Over the time, this may result in adverse left ventricular (LV) remodelling and worse LV function.8–10

Among ROS, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is produced by many enzymes, including, for example, xanthine oxidase, lipoxygenase and, in particular, Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NADPH) oxidase.11 H2O2 shows an important role in ischaemia/reperfusion damage. In particular, the exposure of cultured human cardiomyocytes to H2O2 has determined rapid onset and progressive oxidative cell death.12 Moreover, H2O2 influences platelet activation and promotes vascular dysfunction through thromboxane A2 and isoprostanes formation, which are vasoconstrictors and powerful aggregating molecules derived from lipid peroxidation of esterified unsaturated fatty acids.13–15

Human possesses numerous enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems. Among enzymatic systems, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) plays an important role to prevent potentially deleterious effects of H2O2.16 Thus, the reduced plasma level of glutathione (GSH), a water-soluble tripeptide with a potent oxidant scavenging activity and fundamental substrate for GPx activity, could have a key role in promoting myocardial and endothelial cell damage.17 In fact, a decrease in myocardial GSH content has been observed during ischaemia and reperfusion of the ischaemic myocardium.18

Despite robust evidences regarding the role of ROS in reperfusion injury, currently, in clinical practice, there are no treatments aimed at preventing ROS generation.

Preclinical study of ischaemia/reperfusion demonstrated that timely application of GSH provides better cardioprotection at higher doses.19 Our hypothesis is that the use of GSH might counteract deleterious effect of augmented oxidant activity during reperfusion of STEMI.20 Currently, a GSH solution is available for intravenous usage to reduce side effects of chemotherapy treatment for cancer with a tolerable safety profile, however, it has never been tested in the setting of patients with STEMI.

Therefore, we performed a pilot study to explore whether a short-term intravenous GSH administration, just before and after a primary percutaneous coronary intervention (p-PCI) inpatients with STEMI, was able to reduce oxidative stress and antioxidant status markers, resulting in a reduction of the myocardial damage.

Methods

Study design

GSH2014 is a multicentre, no profit, randomised, double-blind, prospective and placebo-controlled trial. The Department of Heart and Great Vessel ‘A. Reale’, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy was the coordinator centre and designed the protocol (see online supplementary file). Two other centres, ‘Santa Maria’ Terni Hospital and ‘San Giovanni Evangelista’ Tivoli Hospital, both in Italy, were involved in the study as recruiting site.

bmjopen-2018-025884supp001.pdf (67.2KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or public were not involved in the different stages of the study (including the design and the recruitment phase). However, we intend to disseminate the main results to trial participants and will seek patient and public involvement in the development of an appropriate method of dissemination.

Study population and protocol

Between March and August 2017, 157 consecutive patients with STEMI, age >18 years, both sexes, referred to the three enrolling centres for p-PCI were screened to enter in the study. Inclusion criteria were: typical chest pain lasting more than 30 min with pain onset <12 hours, ST segment elevation >0.2 mV in at least two contiguous leads in the initial ECG, successful p-PCI (residual coronary stenosis <20%) and blood sampling for biochemical determinations collected prior to p-PCI.

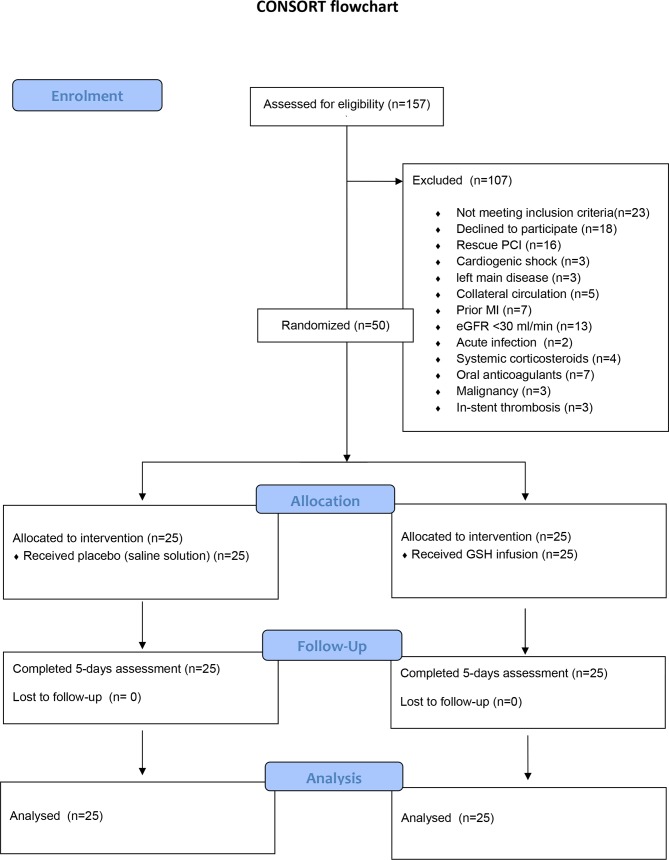

Exclusion criteria were: symptoms duration >12 hours (n=15), rescue PCI (n=16), cardiogenic shock (n=3), left main disease (n=3), evidence of coronary collateral vessels (Rentrop score of 2 or 3 for the area at risk) (n=5), prior myocardial infarction (n=7), estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 30 mL/min (n=13), acute infection (n=2), treatment with systemic corticosteroids (n=4) or oral anticoagulants (n=7), malignancy (n=3), in-stent thrombosis (n=3), lack of consent to participate (n=18). Additionally, eight patients were ineligible because no blood samples were collected before the start of the procedure. Finally, a total of 50 patients were enrolled (see figure 1). The present analysis reported the results of the interim analysis (preplanned in the protocol) on the acute effect of GSH infusion on markers of oxidative stress.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow chart. GSH, glutathione; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

After percutaneous access was obtained, an intravenous bolus of 5000 U of unfractionated heparin was administered, with sufficient supplements (if necessary) to maintain an activated clotting time of ≥250 s during interventions.

After baseline collection of peripheral blood samples, patients were randomised to an intravenous infusion of GSH (2500 mg/25 mL of glutathione sodium salt, Biomedica Foscama Group, Rome, Italy) or placebo (saline solution) over 10 min before p-PCI. The two solutions appeared identical in size and colour to ensure blinding. Study participants, investigators and the laboratory staff remained blinded until the statistical analysis was performed by an independent researcher who was not involved in the study.

Patients underwent p-PCI according to the standard protocols. The use of thrombus aspiration, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition was left to the discretion of the treating physician. Multivessel PCI was performed in a staged fashion (7–10 days from index procedure).

All patients had drug-eluting stents implanted in treated vessels. After interventions, GSH was infused at the same doses at 24, 48 and 72 hours elapsing time. Further blood samples were obtained at the end of the procedure and 5 days from index procedure.

After 60’−90’, a postprocedural 12 leads ECG for ST measurement were performed.

Corrected Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) frame count (cTFC) and TIMI myocardial perfusion grade (TMPG) were assessed after p-PCI as previously described.21 An external Core Lab processed the data (G.P and G.P: independent cardiologists). Digital angiograms were analysed off-line with the use of an automated edge detection system (Cardiovascular Medical System, MEDIS Imaging Systems, Leiden, the Netherlands).

Randomisation and blinding

An individual was not involved in the study assigned codes (using a computer-generated random sequence) to the study treatment with a random allocation of patients to an intravenous infusion of GSH (2500 mg/25 mL over 10 min) or placebo (saline solution) before p-PCI. The interventional cardiologists who performed p-PCI, those who analysed digital angiograms and the laboratory technicians, were unaware of study treatment allocation.

Primary endpoint

The primary endpoint was the change on oxidative stress markers levels after 2 hours from p-PCI in patients treated with GSH as compared with placebo.

Secondary endpoints

The secondary endpoints included the assessment of: (1) changes of oxidative stress markers levels after 5 days from the p-PCI in patients received GSH or placebo; (2) changes in serum cardiac troponin T (cTpT), biochemical markers of myocardial cell damage, in patients received GSH or placebo before and after 5 days from the procedure.

Peripheral blood samples

Blood samples were drawn from antecubital vein, before the start of procedure and after stent deployment in all patients and then collected into tubes without anticoagulant or with 3.8% sodium citrate, lithium heparin and EDTA and centrifuged at 300×g for 10 min to obtain supernatant. All plasma and serum aliquots were stored at −80°C in appropriate cuvettes until assayed.

Markers of oxidative stress and antioxidant system (ie, H2O2, H2O2 breakdown activity (HBA) and 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α)) were analysed in serum samples collected before p-PCI, 2 hours and 5 days after p-PCI. Due to the chemical properties of the oxidative stress markers, to avoid a long-time storage of blood samples and guarantee the laboratory test quality the analyses were performed within 6 months from the collection.

Serum cTpT was measured at admission, before the procedure, 6 and 12 hours after reperfusion, and thereafter once a day up to 5 days. Serum cTpT levels were measured using the ELISA Kit (Elabsciences).

H2O2 production

The H2O2 was evaluated by a Colorimetric Detection Kit (Assays, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA) and expressed as μM. Intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation were 2.1% and 3.7%, respectively.

Determination of % HBA in peripheral serum

The evaluation of the ability to detoxify H2O2 was assessed by the analysis of the HBA in serum with the HBA assay kit (Aurogene, Rome, Italy, code HPSA-50). The per cent of HBA was calculated according to the following formula: % of HBA = [(Ac-As)/Ac] × 100, where Ac is the absorbance of H2O2 1.4 mg/mL and As is the absorbance in the presence of the serum sample.

Serum nitric oxide bioavailability

A colorimetric assay kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, California, USA) was used to determine NO bioavailability by measurement of the nitric oxide (NO) metabolites nitrite and nitrate in the serum. Intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation were 2.9% and 1.7%, respectively.

Serum 8-iso-PGF2α formation

Concentration of 8-iso-PGF2α in serum was measured by validated enzyme immunoassay method (DRG International, Springfield, New Jersey, USA). Intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation were 5.8% and 5.0%, respectively. Values were expressed as pmol/L.

Myocardial function

After 120 min and 5 days from the intervention, LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), LV end-systolic volume (LVESV) and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) were calculated by the biplane Simpson’s rule, as recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography. The mean values of three measurements were used for statistical evaluation.

Sample size calculation

For the present preliminary analysis, the sample size calculation was estimated considering previous data available for 8-iso-PGF2α levels.22 A sample size of 25 patients undergoing GSH infusion provided an intervention study with 80% power to detect a 20% reduction in plasmatic 8-iso-PGF2-α levels measured at the end of successfully reperfusion with respect to the placebo group. We also assumed a 25% SD in each group.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were reported as counts (percentage) and continuous variables as means±SD. We tested the independence of categorical variables by χ2 test and the normal distribution of continuous variables by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. We used Student paired and unpaired t-test, repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Pearson product-moment correlation analysis to evaluate normally distributed continuous variables. Appropriate non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Spearman rank correlation test) were employed for all the other variables. As an overall non-parametric ANOVA, the Friedman test for the analysis of intragroup variations was used. In cases of significance, we compared pair related samples using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The intergroup analysis was performed with the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. Only two-tailed probabilities were used for testing statistical significance. Probability values <0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. All calculations were made with the computer program STATISTICA V.7 (StatSoft).

Results

Twenty-five patients randomly received GSH and 25 placebo. All patients completed the phases of the study (figure 1). All patients had a TIMI flow grade equal to 0 or 1 requiring percutaneous treatment. Clinical and angiographic characteristics of patients are shown in tables 1 and 2. The baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two groups. In both groups, neither side effects during the infusion, nor adverse events during the short observation period were recorded.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population

| Variables | GSH group (n=25) |

Placebo group (n=25) | P value |

| Age (y, mean±SD) | 66±10.7 | 66.9±9.1 | 0.74 |

| Male, n (%) | 15 (60) | 13 (52) | 0.98 |

| Body mass index* (mean+SD) | 26.9±3.9 | 20±3.8 | 0.38 |

| Killip class ≥3, n (%) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 0.47 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 5 (20) | 5 (20) | 1 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 14 (56) | 17 (68) | 0.56 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 11 (44) | 13 (52) | 0.77 |

| Statin use, n (%) | 8 (32) | 8 (32) | 1 |

| Smokers, n (%) | 17 (68) | 13 (52) | 0.38 |

*The body mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres.

Table 2.

Angiographic parameters

| Variables | GSH group (n=25) |

Placebo group (n=25) |

P value |

| Ischaemia time# (min; mean±SD) | 286±88 | 270±96 | 0.85 |

| Thrombus burden ≥3, n (%) | 12 (48) | 11 (44) | 0.77 |

| Thrombus aspiration, n (%) | 13 (52) | 12 (48) | 0.87 |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors, n (%) | 2 (8) | 3 (12) | 0.63 |

| MVD, n (%) | 13 (52) | 11 (44) | 0.77 |

| 2 vessels, | 8 (32) | 5 (20) | |

| 3 vessels, | 5 (20) | 6 (24) | |

| Staged PCI, n (%) | 9 (36) | 5 (20) | 0.89 |

| IRA | |||

| LAD, n (%) | 10 (40) | 9 (36) | 0.77 |

| LCx, n (%) | 5 (20) | 6 (24) | 0.73 |

| RCA, n (%) | 10 (40) | 10 (40) | 1 |

Ischaemia time was defined as the timing between symptom onset and balloon inflation.

GSH, glutathione; GP, general practitioner; IRA, infarct related coronary artery; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx, left circumflex coronary artery; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, Right coronary artery.

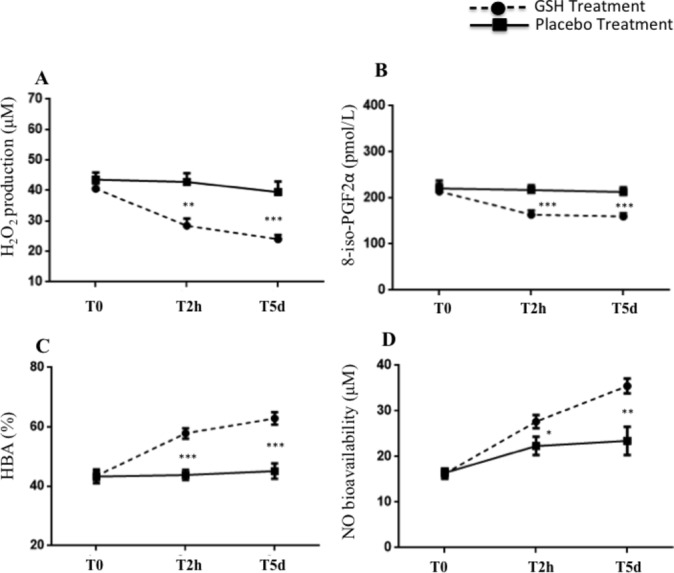

Oxidative stress, antioxidant status and vascular function in peripheral samples. Biochemical data are summarised in table 3. Baseline H2O2 and 8-iso-PGF2α levels were similar between treated patients and controls. After PCI, a significant reduction of H2O2 production and 8-iso-PGF2α levels was observed in GSH group as compared with the controls (figure 2A,B). Moreover, a significant increase in HBA and NO bioavailability was observed (figure 2C,D).

Table 3.

Biochemical data

| Variable | Baseline | Reperfusion 2 hours | Follow-up (5 days) | ||||||

| GSH | Placebo | P value | GSH | Placebo | P value | GSH | Placebo | P value | |

| H2O2

µM, mean±SD Δ |

40.6±8.4 | 43.6±11.6 | 0.305 | 28.4±12 | 42.8±14.1 | 0.0003 | 24±7 | 39.5±17.3 | 0.0001 |

| −12.1±15.2 | −0.7±17.9 | 0.03 | −16.6±11.0 | −4.1±20.14 | 0.009 | ||||

| 8-iso-PGF2α pmol/L, mean±SD Δ |

214.6±81.1 | 211.9±92.1 | 0.91 | 163.6±44.7 | 217.6±51.6 | 0.0003 | 159.9±34.2 | 213.1±50.9 | 0.0001 |

| −50.9±92.9 | −3.3±1.29 | 0.02 | −54.6±62.1 | −1.2±115.7 | 0.02 | ||||

| HBA %, mean±SD Δ |

43.6±7.4 | 43.4±11.9 | 0.94 | 57.9±8.6 | 43.9±8.7 | 0.0001 | 62.9±10.5 | 45.2±13.0 | 0.0001 |

| +14.9±5.5 | +0.4±14.9 | 0.0004 | +19.4±10.2 | +1.8±17.1 | 0.0001 | ||||

| NO µM, mean±SD Δ |

16.3±5.7 | 16.5±4.7 | 0.89 | 27.7±7.2 | 22.4±10 | 0.0356 | 35.5±8.1 | 23.5±15.5 | 0.0013 |

| +11.4±6.8 | +5.8±10.5 | 0.05 | +19.2±9.7 | +7.0±14.7 | 0.002 | ||||

8-iso-PGF2α, 8-iso-prostaglandin-F2α; GSH, glutathione; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; HBA, H2O2 break-down activity; NO, nitric oxide.

Figure 2.

H2O2 production (A), 8-iso-PGF2α formation (B), H2O2 breakdown activity (HBA) (C) and NO bioavailability (D) at baseline, after 2 hours (T2h) and at the 5 days (T5d) from the PCI in patients received GSH (n=25, dashed line) or placebo (n=25, continuous line). Data are expressed as mean±SEM (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). GSH, glutathione; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; NO, nitric oxide; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PGF2α, prostaglandin F2α.

At the 5 days from index procedure, a persistent significant reduction of H2O2 production and a sustained increase in HBA and NO bioavailability was observed in the GSH group as compared with controls (figure 2A–D).

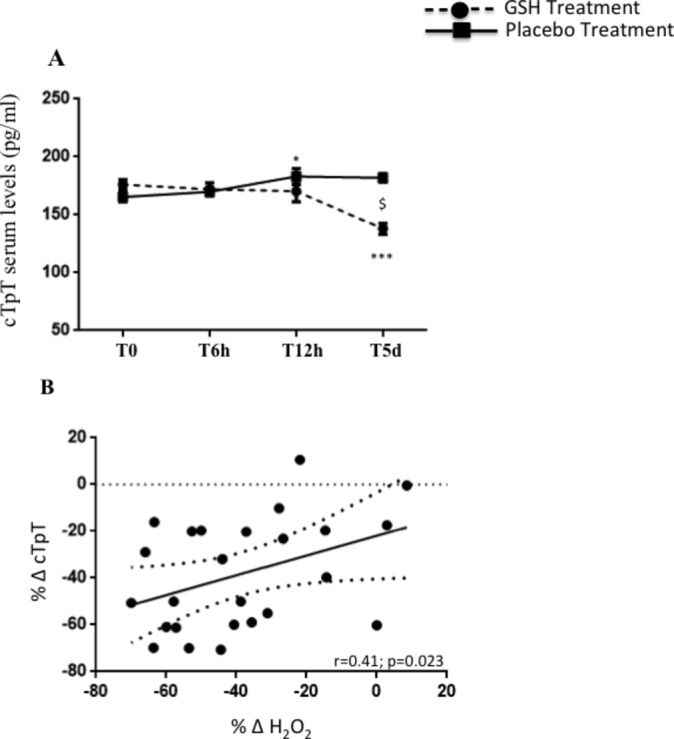

Serological markers of myocardial injury

Baseline cTpT mean values were similar between GSH and placebo groups (176.0±20.9 pg/mL vs 165.4±20.9 pg/mL, p=0.079). At 6 hours, no changes in cTpT values were found in GSH-treated patients (172.1±27.7 pg/mL vs baseline, p=0.065). At 12 hours and 5 days after p-PCI, GSH-treated patients showed a progressive decrease of cTpT levels (170.0±44.7 pg/mL and 137.9±23.7 pg/mL; −21±23.1%, p=0.009 vs baseline). Differently, a significant increase and persistence of high values of cTpT were observed in placebo group (T6, 169.9±16.3 pg/mL, T12, 183.0±34.8 pg/mL and T5d, 181.9±18.0 pg/mL; +12.4%±23.1%, p=0.029 vs baseline) (figure 3A). A modest correlation between percentage changes of H2O2 and cTpT levels from baseline to 5 days was found in the treated group (figure 3B).

Figure 3.

cTpT levels (A) at baseline, after 6 hours (T6h), 12 hours (T12h) and at the 5 days (T5d) from the PCI in patients received GSH (n=25, dashed line) or placebo (n=25, continuous line). Data are expressed as mean±SEM (*P<0.05 vs T0, ***P<0.0001 vs T0, $P<0.05 between groups). Linear correlation between % Δ cTpT and % Δ H2O2 in GSH-treated group (B). cTpT, cardiac troponin T; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; GSH, glutathione; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Myocardial reperfusion indexes

Postprocedural cTFC values did not show a statistically significant reduction between treated and control groups (20.7±7.3 vs 23.4±5.1, p=0.156). Interestingly, six patients (24%) in the placebo group and 15 (60%) patients in GSH group reached lower risk (≤20 frames/s) cTFC class (p=0.019). After PCI, TMPG ≥2 was assessed in 21 patients (84%) and 14 patients (56%) of the GSH and placebo groups, respectively (p=0.064). Of note, 11 patients (44%) of the GSH group only had TMPG=3 (p=0.0002 vs controls). Postreperfusion cTFC values showed a significant correlation with changes of 8-iso-PGF2α (R=0.55, p=0.012) levels from baseline.

Myocardial function

Myocardial function was not different between groups after either baseline or at discharge. There was no significant difference between groups regarding LVEF, LVEDV or LVESV at any time point (table 4).

Table 4.

Left ventricular echocardiographic (ECHO) parameters at baseline and at follow-up

| ECHO parameters | Placebo (n=25) |

GSH (n=25) |

P value |

| Baseline | |||

| LVEDV (mL/m2) | 121.3±17.2 | 124.4±22.3 | 0.44 |

| LVESV (mL/m2) | 65.4±11.3 | 66.3±13.2 | 0.91 |

| LVEF (%) | 47.5±4.9 | 46.9±4.8 | 0.42 |

| Follow-up | |||

| LVEDV (mL/m2) | 118.1±17.8 | 113.2±14.1 | 0.42 |

| LVESV (mL/m2) | 60.9±10.7 | 58.8±12.5 | 0.91 |

| LVEF (%) | 49.1±3.2 | 49.8±3.7 | 0.42 |

GSH, glutathione; LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrates that in the setting of STEMI reperfusion the rapid onset and prolonged antioxidant (scavenging) activity obtained by infusion of GSH before and after primary PCI reduces the oxidative stress markers. The improvement of the antioxidant status resulted in a significant decrease of cardiac troponin, marker of myocardial damage.

Data from experimental and clinical studies suggest that following reperfusion myocardial cells death largely contributes to the final infarct size.23 24 On the other hand, the extent of damaged myocardium is the most important predictor of adverse ventricular remodelling and it is linearly dependent on the amount of myocardial salvage by and after reperfusion. Thus, attenuation of prooxidant state is an important goal in cardioprotective interventions.25 Noteworthy, the serum of GSH-treated patients showed a greater capacity to detoxify H2O2 evaluated by the HBA, an assay that measure the percentage of H2O2 neutralised into the samples.26 We found an early and considerable increase of HBA, with positive effects on myocardial cell survival, assessed by cTpT.

Current evidences demonstrate that oxidant environment promotes cardiomyocyte death in the first few minutes of reflow suggesting the existence of a tight window of effective cardioprotection.27 28 Therefore, ROS-induced injury may continue for weeks to months as a result of activation of programmed cell death. Our data have shown a persistent heightened oxidative status along with decreased scavenging activity in untreated patients. This behaviour makes the duration of pharmacological interventions a central point of cardioprotection strategies. In the present study, GSH infusion, starting just before reperfusion with subsequent administration up to 3 days after, promoted early and sustained increase of serum HBA with attenuated production of H2O2, which was highly related to progressive significant reduction of serological signs of myocardial injury. In addition, our data show a progressive significant decrease of serum cTpT release during the 5 days of reperfusion in the GSH-treated patients compared with the control group resulting in a 21% reduction of myocardial damage. Despite that, in our population, the systolic function was not different between groups after reperfusion, although a trend towards reduced LVEDV was observed in treated patients. A possible explanation relies on the fact that inside the area at risk variable amount of hibernated and stunned myocardium may coexist, thus affecting the prompt recovery of contractility after reperfusion.29

Cells have a number of mechanisms for dealing with the toxic effects of oxygen. One of the most important is connected with the widely distributed tripeptide thiol GSH.16 30 In particular, the GSH redox cycle is a more efficient antioxidant protective mechanism of the heart, which acts by maintaining thiol groups of enzymes and other proteins in their reduced state thus preventing cell membrane lipid peroxidation and limiting cardiomyocytes loss.31 Furthermore, in our study, a close relation between reduced myocardial reperfusion and increased of 8-iso-PGF2α serum levels has been observed, suggesting that oxidative unbalance may be involved in microcirculation functional damage. As previously reported, impaired tissue-level perfusion develops within minutes of established acute revascularisation of ischaemic areas32 and persists for at least 1 week.33 In this context, there is robust evidence that ROS-mediated isoprostanes production contributes importantly to the postreperfusion microvascular impairment.22 34 Current findings implement this observation by demonstrating a sustained production of isoprostanes up to 5 days after reperfusion thereby suggesting their contributory role in the pathogenesis and persistence of microvascular dysfunction that may affect myocardial cell survival. The infusion of GSH before and 24, 48, 72 hours after p-PCI reduced isoprostanes serum levels and their reduction was linked to improvement of myocardial reperfusion indexes. Moreover, the increase in extracellular peroxide oxidants may reduce bioavailability of NO that is thought to contribute to promoting platelet hyperactivity and vasoconstriction.13 In our study, GSH supplementation seems to have a role in preserving NO bioavailability and its vasodilator capacity at microcirculatory level.

The strengths and limitations of the study

The positive effects on reperfusion indexes and on biochemical signs of myocardial necrosis suggest the value of prophylactic and prolonged GSH administration in preventing reperfusion injury. Thus, in patients undergoing p-PCI the infusion of a powerful antioxidant scavenger, such as GSH, may be useful to improve microcirculatory perfusion in order to further blunt the injury of myocardial cells.

Some limitations deserve to be discussed

The small sample size of the study and the lack of morphological assessment of both infarct size and microvascular obstruction extent between the two groups, actually, limit the clinical application of these findings. Within a defined area at risk, the manifestations of ischaemia-reperfusion vascular injury go from reversible functional impairments to irreversible structural damage and contribute to final amount of infarct myocardium. In absence of morphological imaging, the qualitative evaluation of GSH-induced improvement of myocardial reperfusion indexes, as assessed in our study, might only represent the effect of a preserved microcirculatory responsiveness to vasoactive substances (ie, NO) but unable to limit the expansion of myocardial cell damage. Indeed, other mechanisms, such as interstitial oedema and inflammatory reaction, which induce a sustained impairment of microvascular perfusion, may primarily act to increase the amount of irreversible injured myocardium thus promoting adverse ventricular remodelling.

In conclusion, in this pilot study, we have shown that a short-term prophylactic GSH infusion mitigates the negative effects of the excessive and persistent H2O2 formation on myocardial cells. The findings of the present study require to be confirmed through an adequately powered STEMI population. A larger trial with a prolonged follow-up for evaluation of clinical endpoints is needed to confirm the role of GSH administration as cardioprotective therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Authors thank Gennaro Petriello and Gaetano Pero for performing the external assessment of angiographic data (Core Lab).

Footnotes

Contributors: GTa and EM led on the conception, design and writing of the study with substantial contributions to the design, writing, critical review of intellectual content. GTr, AA, AP, NV and RM enrolment of patients. RC, VC and CN provided laboratory analyses. VR and SB provided further essential statistical advice and expertise on the study protocol. FB, LL, MP and CG providing expert clinical support. AG and MD made substantial contributions to the trial design and management.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study has been planned according to principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethic Committee of the coordinator centre and Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) (Date of Competent Authority Decision: 2015-01-13) authorised the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1121–35. 10.1056/NEJMra071667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhu X, Zuo L, Cardounel AJ, et al. Characterization of in vivo tissue redox status, oxygenation, and formation of reactive oxygen species in postischemic myocardium. Antioxid Redox Signal 2007;9:447–55. 10.1089/ars.2006.1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grill HP, Zweier JL, Kuppusamy P, et al. Direct measurement of myocardial free radical generation in an in vivo model: effects of postischemic reperfusion and treatment with human recombinant superoxide dismutase. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;20:1604–11. 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90457-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCully JD, Wakiyama H, Hsieh YJ, et al. Differential contribution of necrosis and apoptosis in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004;286:H1923–35. 10.1152/ajpheart.00935.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dong Y, Undyala VV, Gottlieb RA, et al. Autophagy: definition, molecular machinery, and potential role in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2010;15:220–30. 10.1177/1074248410370327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ørn S, Manhenke C, Greve OJ, et al. Microvascular obstruction is a major determinant of infarct healing and subsequent left ventricular remodelling following primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1978–85. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heusch G, Kleinbongard P, Skyschally A. Myocardial infarction and coronary microvascular obstruction: an intimate, but complicated relationship. Basic Res Cardiol 2013;108:380 10.1007/s00395-013-0380-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bax M, de Winter RJ, Schotborgh CE, et al. Short- and long-term recovery of left ventricular function predicted at the time of primary percutaneous coronary intervention in anterior myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:534–41. 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Araszkiewicz A, Grajek S, Lesiak M, et al. Effect of impaired myocardial reperfusion on left ventricular remodeling in patients with anterior wall acute myocardial infarction treated with primary coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2006;98:725–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ndrepepa G, Tiroch K, Fusaro M, et al. 5-year prognostic value of no-reflow phenomenon after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:2383–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Byon CH, Heath JM, Chen Y. Redox signaling in cardiovascular pathophysiology: A focus on hydrogen peroxide and vascular smooth muscle cells. Redox Biol 2016;9:244–53. 10.1016/j.redox.2016.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tanimoto T, Parseghian MH, Nakahara T, et al. Cardioprotective Effects of HSP72 Administration on Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1479–92. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.07.762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pignatelli P, Pulcinelli FM, Lenti L, et al. Hydrogen peroxide is involved in collagen-induced platelet activation. Blood 1998;91:484–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Freedman JE. Oxidative Stress and Platelets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008;28:11–16. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Basili S, Pignatelli P, Tanzilli G, et al. Anoxia-reoxygenation enhances platelet thromboxane A2 production via reactive oxygen species-generated NOX2: effect in patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011;31:1766–71. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.227959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Takebe G, Yarimizu J, Saito Y, et al. A comparative study on the hydroperoxide and thiol specificity of the glutathione peroxidase family and selenoprotein P. J Biol Chem 2002;277:41254–8. 10.1074/jbc.M202773200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jin RC, Mahoney CE, Coleman Anderson L, et al. Glutathione peroxidase-3 deficiency promotes platelet-dependent thrombosis in vivo. Circulation 2011;123:1963–73. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.000034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singh A, Lee KJ, Lee CY, et al. Relation between myocardial glutathione content and extent of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Circulation 1989;80:1795–804. 10.1161/01.CIR.80.6.1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hinkel R, Boekstegers P, Kupatt C. Adjuvant early and late cardioprotective therapy: access to the heart. Cardiovasc Res 2012;94:226–36. 10.1093/cvr/cvs075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Truscelli G, Tanzilli G, Viceconte N, et al. Glutathione sodium salt as a novel adjunctive treatment for acute myocardial infarction. Med Hypotheses 2017;102:48–50. 10.1016/j.mehy.2017.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Henriques JP, Zijlstra F, van ’t Hof AW, et al. Angiographic assessment of reperfusion in acute myocardial infarction by myocardial blush grade. Circulation 2003;107:2115–9. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065221.06430.ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Basili S, Tanzilli G, Mangieri E, et al. Intravenous ascorbic acid infusion improves myocardial perfusion grade during elective percutaneous coronary intervention: relationship with oxidative stress markers. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2010;3:221–9. 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brener SJ, Maehara A, Dizon JM, et al. Relationship between myocardial reperfusion, infarct size, and mortality. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2013;6:718–24. 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Musiolik J, van Caster P, Skyschally A, et al. Reduction of infarct size by gentle reperfusion without activation of reperfusion injury salvage kinases in pigs. Cardiovasc Res 2010;85:110–7. 10.1093/cvr/cvp271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hausenloy DJ, Garcia-Dorado D, Bøtker HE, et al. Novel targets and future strategies for acute cardioprotection: Position Paper of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cellular Biology of the Heart. Cardiovasc Res 2017;113:564–85. 10.1093/cvr/cvx049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carnevale R, Nocella C, Pignatelli P, et al. Blood hydrogen peroxide break-down activity in healthy subjects and in patients at risk of cardiovascular events. Atherosclerosis 2018;274:29–34. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Piper HM, Abdallah Y, Schäfer C. The first minutes of reperfusion: a window of opportunity for cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res 2004;61:365–71. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhu X, Zuo L. Characterization of oxygen radical formation mechanism at early cardiac ischemia. Cell Death Dis 2013;4:e787 10.1038/cddis.2013.313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bolli R, Marbán E. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of myocardial stunning. Physiol Rev 1999;79:609–34. 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Freedman JE, Frei B, Welch GN, et al. Glutathione peroxidase potentiates the inhibition of platelet function by S-nitrosothiols. J Clin Invest 1995;96:394–400. 10.1172/JCI118047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meister A. Glutathione-ascorbic acid antioxidant system in animals. J Biol Chem 1994;269:9397–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reffelmann T, Kloner RA. Microvascular reperfusion injury: rapid expansion of anatomic no reflow during reperfusion in the rabbit. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2002;283:H1099–107. 10.1152/ajpheart.00270.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rochitte CE, Lima JA, Bluemke DA, et al. Magnitude and time course of microvascular obstruction and tissue injury after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1998;98:1006–14. 10.1161/01.CIR.98.10.1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xu Y, Huo Y, Toufektsian MC, et al. Activated platelets contribute importantly to myocardial reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006;290:H692–H699. 10.1152/ajpheart.00634.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025884supp001.pdf (67.2KB, pdf)