Abstract

Objectives

To explore the reasons why lay community first responders (CFRs) volunteer to participate in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest response and the realities of their experience in providing this service to the community.

Design

A qualitative study, using in-depth semistructured interviews that were recorded and transcribed. Thematic analysis was undertaken and credibility checks conducted.

Setting

Nine geographically varied lay CFR schemes throughout Ireland.

Participants

Twelve experienced CFRs.

Results

CFRs were motivated to participate based on a variety of factors. These included altruistic, social and pre-existing emergency care interest. A proportion of CFRs may volunteer because of experience of cardiac arrest or illness in a relative. Sophisticated structures and complex care appear to underpin CFR involvement in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Strategic and organisational issues, multifaceted cardiac arrest care and the psychosocial impact of participation were considered.

Conclusions

Health systems that facilitate CFR out-of-hospital cardiac arrest response should consider a variety of relevant issues. These issues include the suitability of those that volunteer, complexities of resuscitation/end-of-life care, responder psychological welfare as well as CFRs’ core role of providing early basic life support and defibrillation in the community.

Keywords: public health, first responders, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to explore both the reasons community first responders (CFRs) volunteer to provide cardiac arrest response and the realities of CFRs experience in providing this care.

As a qualitative study, this research has facilitated the acquisition of novel data that generate important hypothesis with significant implications for systems that deploy CFRs to cardiac arrest.

Further research is needed to explore the findings in greater detail and to establish whether the results of this research apply more generally.

Introduction

Background

Approximately 275 000 people are treated for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) in Europe annually but only 1 in 10 survive.1 Successful resuscitation is largely determined by the early availability of CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) and defibrillation within the community. The efficacy of these treatments is critically time sensitive.2 Community first responders (CFRs) are volunteers who live or work within a community and are organised in a framework that offers OHCA care in that community to supplement the standard ambulance service response.3 By virtue of their presence in the community, CFRs may reach patients earlier than the statutory ambulance service and thus shorten the collapse to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)/defibrillation interval. The role of OHCA CFR is thus to provide early basic life support care involving CPR and defibrillation. International research has demonstrated that CFRs can play a significant role in early CPR, defibrillation and potentially OHCA survival.4–7

Ireland has a population of 4.7 million.8 Approximately 2000 OHCAs where resuscitation is attempted are dealt with by the Irish ambulance services annually; although survival is rising, it remains in the region of seven percent.9 One-third of Ireland’s population live in rural areas.9 Only 9% of rural Irish OHCA patients receive a statutory ambulance response within the national target timeframe of 8 min or less; ultimately, rural OHCA patients are less likely to be discharged alive from hospital.10 Given Ireland’s settlement pattern, the deployment of CFRs to OHCA has been embraced as a key public health response to OHCA, and CFR schemes have been developed both in urban and rural areas. In Ireland, CFRs are volunteers who are activated by text message alert from the statutory ambulance service. CFR categories include off duty ambulance service staff, fire service CFRs, family doctors and lay CFR groups.11 This study focuses on lay CFR groups. Several dozen people may join any individual group. Although groups do not have professional medical responsibilities, off duty healthcare staff sometimes also join and contribute as volunteers. Where off duty healthcare staff operate in lay CFR groups, their scope of practice is restricted to that of other lay CFRs. Accreditation occurs through the National Ambulance Service and CFRs ‘go live’ when training, equipment, activation and support structures are in place. Most lay CFR groups operate by having a roster of two-person teams who carry a dedicated alert phone, defibrillator and basic life support equipment to cover defined periods for their area. When an alert is received, the CFR(s) respond using normal driving rules.

Importance

Despite the observation that CFRs are established as a key element of OHCA response in Ireland and over 500 individual response schemes (including approximately 200 lay CFR groups) are now in place, virtually no data are available concerning CFR activities. Research in this area is urgently required.

The involvement of lay CFRs in OHCA resuscitation is unique in terms of a healthcare systems response to a life threatening emergency situation. It is not without risk. It involves the deployment of volunteers with minimal training to the most high acuity medical situations in their own communities and has raised potential concerns in terms of professional gatekeeping, training and supervision.5 Furthermore, with an incidence rate in Ireland of 50 per 100 000 population per year, OHCA is likely to be a rare event for individual CFR schemes especially in rural communities.9 Ultimately, the engagement of CFRs will need to be sustained over time. Despite the observation that CFR deployment has emerged as an increasingly common OHCA intervention internationally and is being embraced by various EMS systems, very little research has been carried out to explore the motivation, experience or perceptions of this key group of people.

Goals of this investigation

The aim of this study is to explore the reasons why lay CFRs volunteer to participate in OHCA response and the realities of their experience in providing this service to the community.

Methods

Study design and setting

A qualitative study, using in-depth semistructured interviews followed by thematic analysis was undertaken. The study setting was geographically distributed lay CFR groups, both rural and urban throughout Ireland. The type of qualitative approach employed was phenomenological; the research process focused on understanding the participant’s view of self and their surrounding world in the specific context of OHCA response.12 The methodological approach was informed by the standards for reporting of qualitative research outlined by O’Brien et al13 and the analytic approach outlined by Braun and Clarke.14 Steps to ensure credibility in the analysis process were also conducted and are described below.

Selection of participants

A purposive approach to sampling was undertaken, with recruitment through Ireland’s dedicated CFR network (CFR Ireland). In order to gain a spread of perspectives and experience, the research team specifically requested that CFR Ireland help recruit ‘twelve CFRs with experience of OHCA response from four different geographical areas’. All CFRs dispatched by the ambulance service in Ireland have undergone at minimum, a specific half day training course in basic life support and AED use. In addition, each participant was required to have personal experience of responding to cardiac arrest in the community. No specific incentive or reward for participation was offered beyond highlighting the value of contributing to increased understanding of this scientific field. A study information leaflet was provided to each participant prior to enrolment. In advance of the study, we considered the potential that topics discussed might be distressing for participants, and it was made clear that participants were free to pass on any topics they found uncomfortable. Provisions were made to refer participants to their own family doctor if distress was experienced from participation in the study.

Data collection

One researcher (TB) conducted all interviews, which were face to face and took place at various locations convenient for the relevant CFR(s). Interviews took place between September and December 2017. Prior to conducting interviews TB and SG (an experienced qualitative researcher) formally planned the interview process; potential biases were considered via a reflective process, and a formal reflexivity statement was composed. The researcher (TB) aimed to identify any personal biases that might affect the research process or results.

The observation that the researcher came from the ‘world view perspective’ of a doctor who himself participated in cardiac arrest response was considered in detail at this stage. Via a personal reflexivity statement, the researcher attempted to consider any pre-existing biases he might possess related to the factors that motivate CFRs to participate in OHCA care and the nature of CFR OHCA care. The researcher reflected on any previous interactions with CFRs and attempted to consider and make explicit any preformed perspectives in an effort to limit how personal bias might influence the research process.

A semistructured interview format was undertaken to allow flexibility of response and follow up ‘unplanned’ questions to facilitate a participant led exploration of topics.12 This approach involved a preprepared interview guide/schedule to facilitate overall structure but did not require rigid adherence to precise wording of questions or the order in which they were asked.15 The written interview schedule considered two key domains: (1) the participant’s motivation to participate in the scheme and (2) the realities of providing first response to cardiac arrest in the community. Each domain involved standard initial open-ended ‘prompt’ questions and flexible ‘follow on’ questions based on the interviewees’ initial responses. Informed written and verbal consent were obtained before commencing each interview. The initial interview acted as a pilot where the candidate was asked to give feedback and suggestions regarding the interview process. Immediately following each other interview reflections concerning interview process and content were recorded as field notes in a research diary. All interviews were recorded using a Zoom H2n professional grade recorder and later professionally transcribed. The transcripts were then checked against the tapes for accuracy and minor corrections were made as necessary.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using the thematic analysis framework outlined by Braun and Clarke.14 Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing and reporting themes within data. It involves six phases: ‘Data familiarisation’, ‘Generating initial codes’, ‘Searching for themes’, ‘Reviewing themes’, ‘Defining and naming themes’ and ‘Producing a report’. Initial coding and all further phases were conducted using NVivo V.11 for Windows. An experienced qualitative researcher (SG) acted as coresearcher at all stages of the analytic process to ensure credibility. SG coded a sample of the dataset (one interview) independently and reviewed all candidate and final worked out themes with TB thus supporting a reflexive process throughout data analysis. The analysis produced a structure of themes in relation to key domains that reflect the focus of the study.

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public were involved in the design or conduct of this research.

Results

Characteristics of the study subjects

CFR Ireland contacted 15 geographically disparate CFR groups on behalf of the research team. Selection of groups was a matter for CFR Ireland who reported to the research team that they ‘selected groups and individuals based on urban or rural, large or small, very busy or not so busy, gender mix and attempting to give a national spread’. CFR Ireland reported they ‘contacted 15 groups to increase the likelihood of ultimately a good spread of 12 different CFRs’. Where a group expressed interest, permission was obtained for the research team to contact a nominated person from that relevant group directly. Twelve groups offered permission, two of whom were identified as new groups unlikely to have yet participated in a cardiac arrest response and thus were excluded from the study.

Ultimately 9 of the remaining 10 groups participated in the research. Twelve CFRs of varying ages and representing those nine geographically distributed lay CFR groups self-selected to participate. Given the sensitivity of the topic area, detailed demographic participant elements were not profiled quantitatively; however, all participants described significant experience of OHCA response over a number of years. A total of 10 in-depth interviews were conducted; on two occasions, two CFRs representing a single CFR group chose to be interviewed together. Two further participants interviewed were from one individual CFR group. All interviews were included in data analysis. Gender was equally distributed among participants. Most participants occupied a senior role within their respective CFR group by virtue of the fact that they had additional responsibility for the coordination or day-to-day running of their CFR scheme in addition to providing OHCA response. Two participants had a professional healthcare background. Interview duration ranged from 45 min to 108 min, median duration was 58 min. No participants elected to ‘pass’ on any topics raised in the interviews and no psychosocial distress was reported related to participating in the study.

Main Results

Domain 1: motivation to participate

The results of thematic analysis considering the domain of ‘motivation to participate’ are reported in table 1. Participants outlined that some CFRs were motivated to volunteer by an interest in emergency care. Some CFRs worked as healthcare professionals although this could be challenging as the extra burden of knowledge could distract from the core basic life support tasks of a CFR. CFRs were also motivated to participate based on a desire to give back to the community or as a means of social engagement. The inherent satisfaction in ‘saving a life’ was also highlighted. A proportion of CFRs were motivated to volunteer based on past experience of OHCA incidents. For some, this was a response to having felt unprepared and unskilled in such a situation. For others, the desire to volunteer related to a family experience of illness or OHCA. Although many such volunteers were considered to cope well psychologically with the CFR role, respondents noted that for some individuals, engaging in CFR activities was known to have caused psychological distress. A minority population of those that volunteer appeared to be motivated by the dramatic elements of emergency care. One participant termed this group ‘Blue Light Junkies’. Most participants appeared to have an awareness of this volunteer type and some considered their attributes to be incompatible with the calm affect and strong interpersonal skills considered necessary for the CFR role.

Table 1.

Motivation to participate: key themes

| Theme | Theme description | Illustrative quote(s) |

| Existing skills and interest | Volunteer CFRs may already have an interest in emergency care, be healthcare professionals or come with first aid training. CFR activity might also be a means by which a lay person with an interest in healthcare can pursue this interest. | CFR10: What we found is, it tends to be people who have some sort of a first aid background already that do it. So a lot of the people that joined us initially would have been the first aider in their rugby club, or the first aider in work, or something like that. |

| Giving back to the community | CFR was seen as a means of doing something good for and giving back to the ‘community’, thus resulting in personal satisfaction. | CFR9: Like that you’re there, you’re involved, giving something back, but it’s for free, it’s voluntary. It’s brilliant, you know. |

| Getting involved with the community | Participation in CFR could be a means of engaging with the community and making social contacts. | CFR6: I could never give back what I got out of the scheme, could never, after 12 years. I could never repay what I’ve got. I’ve met some of the… some of my closest friends now, through the scheme. |

| Saving a life | Participation in CFR offered the potential to ‘save a life’. This had inherent personal satisfaction. | CFR9: But for like the good ones where it’s an arrest you get there, you shock them, they’re back and discharged back home. Like there’s no better feeling than actually being involved with that. |

| Personal experience of OHCA | Personal experience of OHCA was a potential motivator. This could involve a situation where a volunteer had encountered OHCA and felt helpless/was left with a feeling of needing to act on this. It could also involve family members of OHCA victims. |

CFR8: Well for me personally it was an incident I witnessed in a shopping centre… So unfortunately for the man, I suppose for everyone involved, the man died and passed away and I felt very helpless and I kept saying ‘God this is tragic, because nobody knew what to do. We just stood around.’ And I said ‘Look, I hope I’ll never feel like this again. I’m going to learn’. CFR1: A cohort have family issues, as in, something happened, or they have a child who maybe has cardiac problems, etcetera. That, I might come back to that later, that can be challenging. |

| ‘Blue Light Junkies’ | A minority of individuals can be motivated to participate based on a desire to engage with elements of OHCA response that are perceived as exciting or dramatic. | CFR2: Yeah, I think some people probably have the, what do we refer to it is. I can’t think actually the name we use, but basically they want to be Superman and they want to rush in and save people’s lives and they’re only dying to paint ‘battenbergs’ on the side of their cars and get blue lights – which obviously you’re not allowed to do – but there is that element, that some of the people in the room, it’s a real gung-ho macho kind of a thing. |

CFR, community first responder; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Domain 2: the realities of providing first response to cardiac arrest in the community

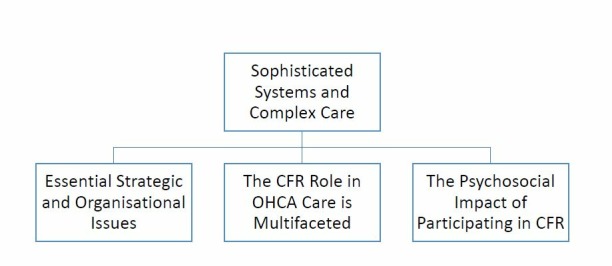

A thematic map considering the domain of ‘the realities of providing first response to cardiac arrest in the community’ is shown in figure 1. A unifying overall umbrella theme was evident reflecting the observation that the systems underpinning CFR care are sophisticated and the care provided is complex. Three key follow-on themes were evident: ‘essential strategic and organisational issues’, ‘the CFR role in OHCA is multifaceted’ and the ‘psychosocial impact of participating in CFR’. A number of follow on subthemes were also apparent and are described below.

Figure 1.

Thematic map: realities of providing first response to cardiac arrest in the community. CFR, community first responder; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

The first key theme ‘essential strategic and organisational issues’ is reported in table 2, with subthemes identified by respondents. Participants highlighted the importance of community engagement, fundraising and cascading basic life support to the community. There was recognition that although not everyone might be suitable for the CFR role, there were various other ‘support’ roles available to those wishing to volunteer. There was evidence that CFR groups had developed processes of screening and supported induction for new members. The voluntary/community nature of the scheme was considered to pose challenges in terms of group dynamics and conflict. The importance of training for the role of CFR was highlighted. Anxieties in terms of locating patients in OHCA quickly were discussed as was the value of smartphone mapping and ‘eircodes’ (postcodes) in expediting this process. Safe driving was an evident priority. There were conflicting perspectives on CFR scope of practice. In general, CFR interactions with ambulance services management were considered positive; however, there was some frustration evident around a lack of financial support and a perceived high level of caution on the part of health services management around CFR activities.

Table 2.

Essential strategic and organisational issues

| Subtheme | Subtheme description | Illustrative Quote(s) |

| Community engagement | Community engagement was important for recruitment, fundraising and cascading basic life support skills/AEDs to the community. | CFR5: When we’re training we actually go out into the community like. Housing estates, the kids are fantastic, once they see something different going on they are like that. The word spreads so then we have a crowd. So, yes, so it is basically from being out around in the community doing different demonstrations, fundraising, all that kind of stuff. |

| Recruitment, screening and potential for different volunteer roles | Ongoing recruitment was important. Screening was important as not everyone is suitable for the CFR role, but it is also not possible to exclude individuals as a community organisation. A variety of additional roles outside of responder exist. | CFR1: We have had a couple of situations where (people) appear to have come and done the training to get it on their CV, and then never shown up again. The other piece is, it’s very much, we do need to see whether they are ’a fit' in terms of going into somebody’s house in a very sensitive situation, we need to work out, A, have they got the skills, and B, have they got… more the people skills and the appropriateness skills. So we don’t rush them in. CFR2: I mean most of the people are very competent but there are people there that I just wouldn’t be 100% sure of. But unfortunately, in a community group, you know, unless I think somebody is actually dangerous, we’re not in a position to tell them to go away. |

| Supporting new members | Supported induction was important. | CFR3: When anyone (is) first kind of qualified they’re told you can only go if responder A is on and you’re responder B and only if they’re going because it’s not good for you to be going on your own for the first few calls. |

| Training | Ongoing training was important. | CFR4: We train twice a month now, you know. And we change all the scenarios and that we sit down and have discussions about - as to how did our last call go? Is there something else that maybe you should have done when you think back on it? Or what difficulties did you have on that call? |

| Dispatch | Time pressures exist in locating the patient in OHCA. Potential technological solutions such as smart phone mapping were used. Safe driving was a priority. |

CFR1: I think the anxiety about getting there. I suppose the biggest anxiety for the volunteers is, will I be able to find the house. That is the thing that keeps them awake at night. CFR10: Google Maps is the answer to pretty much everything. CFR3: So you have to remain calm, you have to abide by the rules of the road, obviously, and that can be a bit stressful if you hit traffic but you just have to. You just have to say to yourself I’m just doing my best and the ambulance is on its way anyways. |

| Group dynamics and conflict | The voluntary nature of community groups was highlighted as a challenge in terms of group conflict and cohesion. | CFR3: And, as with all volunteer groups, there will be issues thrown up. I know one person did leave because she didn’t feel welcomed or something, now I think that was probably on her side a bit. So there’s going to be issues like that with any group of volunteers. |

| Scope of practice | Conflicting opinions existed re CFR scope of practice; some believed ‘best to stick to the basics’ while others want to do more. |

CFR12: I keep saying to my guys, our guys, ‘Get this right first and then we might give a look at something else’, … but definitely I wouldn’t be that keen to broaden the range. I don’t see our guys really behaving themselves and concentrating on their skill level. CFR4: We’ve a paramedic on board but we’re not allowed to use oxygen. There’s loads of things that we can’t do that we’re trained in doing, you know. Then there’s new drugs coming in that, has got the licence to you know certify us in administrating these drugs and that and we’re not even allowed to use this. |

| Support and friction at the health service interface | Key health services individuals and structures were considered to support CFR; however, limited financial support was available. At times some frustration with what was perceived as an overly cautious health services approach was evident. |

CFR1: So (’X') is the CFR coordinator when there was nobody doing anything, and they have been brilliant. So we had to work it all out, the policies weren’t in place at the time, they’re… now the policy is excellent. Whoever wrote it, seemed to cover every base, and I know it’s being updated currently. CFR12: It’s not easy sometimes dealing with the HSE. They wouldn’t be too quick to change or make up their minds about stuff. Or at the same time we’d be looking at well our neighbours are dying, and you can’t make your mind up, so we figure stuff out. They’re very fearful that there’s information out there but it’s out there anyway, so I think they’re fearful of making a mistake. I think for me looking at it from a non-HSE employee, they’d rather do nothing than make a mistake. |

CFR, community first responders; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

The second parent theme ‘the CFR role in OHCA care is multifaceted’ is reported in table 3. A variety of CFR roles in OHCA care were highlighted ranging from providing early basic life support (BLS) care in advance of the ambulance service, assisting the ambulance service on their arrival and the provision of psychosocial support for families. As the ‘first responders’ to OHCA, CFRs had the potential to encounter challenging situations around end-of-life care. Difficulties around ‘do not resuscitate’ directives and conflicting family perspectives on the appropriateness of resuscitation were discussed. CFRs strongly valued being involved in the care process by paramedics. A minority of paramedics were perceived as having negative attitudes towards CFRs possibly because of a perspective that CFRs were undermining the paramedic role by providing a low cost alternative. The provision of psychosocial support to families was perceived as routine, important and in fact a significant overall proportion of the care CFRs provided in OHCA.

Table 3.

The CFR role in OHCA care is multifaceted

| Subtheme | Subtheme description | Illustrative quote(s) |

| Providing early BLS (basic life support) | The provision of early BLS was of fundamental importance. Complex end-of-life situations could be encountered but the BLS element of care was considered straightforward. | CFR6: Look it, although it’s stressful and it’s very difficult, the calls you will go on will be very difficult, but what we have to do is very simple, it’s very straightforward - CPR and use a defibrillator, nothing else matters. |

| Dilemmas | As ‘first to respond’ CFRs could encounter situations where difficult decisions had to be made in terms of what actions were appropriate. | CFR2: We’d one person in particular whose family absolutely wanted CPR done and the nurse was saying look, he’s not well… and they insisted, so we did it but … It raises big moral issues for me |

| Assisting ambulance staff | CFRs were happy to assist ambulance staff as necessary and appreciated when paramedics involved them in the care process. Relationships with paramedics were mostly positive, but a minority of paramedics appeared to view CFRs negatively. |

CFR11: I have gone in the back of the ambulance doing the breaths the whole way to the hospital, it was brilliant, absolutely brilliant but for the lads to let me do that, you know? CFR3: And we get quite a few who are quite rude and not happy to see us there, I’ll be honest. But I would say it’s actually only 5% but you’re so almost offended by them… I would say if you were starting out as a first responder on your first few calls and you came across some of the guys that we’ve come across, you might be thinking, you know, what’s the point in me coming out here. |

| Caring for families | Providing psychosocial support to patient’s families was considered a definite and significant component of the care CFRs provide. Providing this aspect of care was satisfying for CFRs. | CFR2: Their loved one has just died and they’re there on their own, you know. So, it is very much a social, there’s a huge social care element to it and it’s something I constantly emphasise to people when they’re talking about joining is that the saving a life bit will happen once in a blue moon. That really what this is about is being there, that we are there with the people as opposed to them being scared and in pain and on their own. |

CFR, community first responders; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

The final key theme ‘the psychosocial impact of participating in CFR’ is reported in table 4. Participating in CFR had the potential to affect volunteers in a number of ways. For some the burden of being ‘’on call’’ had been a challenge in terms of a sense of hyperarousal in anticipation of an alert. Participation in CFR could at times result in exposure to emotionally traumatic situations, and there was evidence that such situations had affected CFRs in their aftermath. For some, the interaction with family members at an OHCA event had resulted in changed relationships and social avoidance going forward. CFR well-being was a key issue for participants, who expressed a sense of personal responsibility for this element of participation. Internal debrief in the immediate aftermath of an incident was frequently employed as a coping strategy. Formal CFR supports such as critical incident stress management (CISM) were evident and highly valued by participants.

Table 4.

The psychosocial impact of participating in CFR

| Subtheme | Subtheme description | Illustrative quote(s) |

| The burden of being ‘on-call’ | Being ‘on call’ could be burdensome for a proportion of CFRs. CFRs could perceive a duty to provide cover and a sense of guilt when unable to respond. |

CFR: He had said he was just finding it more and more and more playing on his mind. The phone, not calls that he was on, he was just more conscious that he was on call. So if he couldn’t take it at night, because he was waiting for it to ring. CFR8: I found it a little bit of a burden at times, in that, but I was trying to cover too much and then I realised you just can’t slot into every vacant slot |

| Difficult and distressing situations | CFRs were exposed to difficult situations that could have significant psychological effects in their aftermath. |

CFR10: It was a horrible experience, in terms of, you could hear screaming as you were approaching the driveway… it was like walking into a little horror film. CFR12: And it was just dreadful what she had to endure and she happened to be on her own, she was the first on the scene. She happened to be on her own, but for me I probably wouldn’t have gone in but she did. Fair play to her she went in and… they were in bits. There was sadness, there was anger, there was fighting, there was everything. Everything thrown at her. Dreadful and it took a long time to get over it and she is still responding. |

| Changed relationships with the community | Providing CFR care could result in changed relationships with members of the community. | CFR7: People do actually avoid you. And when it was actually said to me, they’re not actually avoiding you, they’re avoiding the flashbacks because when they, the last time they seen you. It brings back the memories of the last time. Well hang on, the last time I seen ‘X’ he was on top of my mother pumping on her chest and blowing into her mouth. And all the flashbacks come back. |

| Volunteer well-being and supports | CFR well-being was a priority for CFR groups. Debrief and formal health services support in the form of CISM were important. |

CFR4: It’s very important when you stay in contact with all your members and find out their welfare. Because as a coordinator within a unit, it’s your responsibility to make sure that all your members are safe, you know. CFR5: We have had some bad callouts but like I said we go back to the house and put the kettle on and we just go through the whole scene and just make sure everyone is alright, how are they feeling, you know. CFR1: The CISM training is very good, it’s the awareness piece. And I have to say that CISM sessions at the CFR conferences have been excellent. |

CFR, community first responder; CISM, critical incident stress management.

Discussion

The deployment of lay CFRs to OHCA represents a key mechanism by which early CPR and defibrillation can be made available in the community, which in the context of the current evidence base surrounding OHCA resuscitation is the priority.16 Where CFRs can reach OHCA patients quickly, increased rates of survival can be achieved.17 It is thus unsurprising that the narrative of CFR care has to date focused on the provision of early CPR and defibrillation. However, this study shows that CFR care has evolved to be a sophisticated entity that includes complex decision making, a significant component dedicated to the provision of psychosocial support for bystanders and family members and also teamwork with ambulance service staff during ongoing resuscitation. It is striking that participants raised complex moral and psychological subthemes as well as the ongoing welfare both of CFR volunteers and the families of OHCA patients in their communities. These issues highlight the need for a broad preparation and longer term support for the CFR role. A focus on CPR skills and driving safety may have been perceived as the critical components of the role in the past, but the material gleaned in this study shows that those who arrive first at the scene of an OHCA can be confronted with the need to make complex decisions immediately and under pressure. Preparation for that decision-making process and support in dealing with its consequences are familiar themes in professional advanced life support resuscitation training; this study highlights their relevance for CFR volunteers also. When lay volunteers arrive at a home in which family members are conflicted about providing resuscitation to a loved one, immediate practical, moral and personal challenges arise, few of which have procedures-driven responses. The personal qualities and preparation of the CFR volunteers are the attributes that come into play in such scenarios according to study respondents. Those attributes may need to be more strongly ‘screened for’ and supported among volunteers.

Complexity emerges from this study as a significant finding. While CPR and defibrillation are noted by respondents to be straightforward skills, the personal and systems issues associated with the role are highly complex; respondents identify many issues that may be familiar within medical, nursing and paramedic training but which have received limited attention within ‘volunteer’ roles. In further developing the number and perhaps scope of new CFR schemes, the accreditation and support agencies should consider how best to address these demands.

Many of the factors that motivated CFRs in our study (prior relevant experience, a sense of altruism and the desire to engage with and make a contribution to the community) have been described previously.18–21 The issue of close personal experience of OHCA or illness in a family member as a motivator is worthy of consideration, given the possibility of associated psychological distress. Sustained CFR participation may be related to the nature of CFR interaction with paramedics. Strategies that promote positive interactions (such as involving CFRs in the care process as appropriate and educating paramedics as to the role of CFRs) could be employed by ambulance services as a mechanism to formerly support CFR retention. The volunteer phenotype described by one participant as ‘blue light junkies’ has not to our knowledge been previously described in the CFR literature. Participants expressed conflicting views as to whether such individuals possessed the necessary attributes for competent CFR care. The issue of ‘problematic individuals’ highlights an entity unique to voluntary and community organisations providing healthcare services. In contrast, professional services have a mandate and mechanism to exclude individuals considered unsuitable for the role.

Concerns as to the psychological impact of participation in CFR have been highlighted in the literature.18 19 22 Previous studies have however suggested that the incidence of significant prolonged adverse effects are likely to be low.23 24 Participants in our study highlighted the psychologically challenging situations faced by CFRs and the importance of CFR well-being. This issue was actively managed by processes of volunteer screening, training, supported induction, debrief and CISM. CFRs who continue in the role may do so as a direct result of such mechanisms. Such individuals may also exhibit a resilience phenomenon.21 It is however also possible that those who discontinue participation have suffered psychological ill effects. In evaluating the potential adverse effects of dispatching CFRs to OHCA such a population are likely to be of critical relevance but difficult to follow.

Limitations

Our study has important limitations that should be considered when interpreting its results. The number of participants interviewed balanced the requirement for rich data acquisition with the pragmatic issue of conducting multiple in-depth face-to-face interviews at varied geographical locations. We adopted the approach to sampling advocated by Braun and Clarke, who do not suggest the application of the principle of ‘data saturation’ in sample size calculation but instead highlight the exploratory and interpretative ethos of thematic analysis and the requirement to offer a compelling and coherent analysis of the data by doing justice to its complexity and the nuance contained within it.14 15 25 Ultimately, our analysis produced an evolved structure of themes in relation to key domains that reflect the focus of the study and its research questions. Rich data were acquired from 12 participants that generated novel findings and important hypothesis with significant potential implications for all health systems that dispatch CFRs to OHCA. Further research is ultimately needed to explore significant individual themes in greater depth and to establish whether the findings of this research apply more generally. Further qualitative research guided by the themes identified in this study as well as quantitative national and international surveys of CFRs should now be considered.

Although the semistructured interview is a flexible and adaptable way of generating findings, the lack of standardisation can raise concerns about reliability and biases are ultimately difficult to rule out.12 The fact that participants were recruited via CFR Ireland and self-selected to participate could result in selection bias. This strategy did however provide a sample of experienced CFRs, many of whom had strategic roles within their organisations and ultimately facilitated significant depth of topic exploration and the development of a breadth of evolved themes at data analysis. The observation that the study participants all had significant experience of OHCA response and had senior roles within their individual schemes warrants some consideration. Individuals new to CFR or with less experience of providing clinical care may have different perspectives.

One participant was known to the interviewer prior to the research thus potentially introducing bias in the topics discussed. The participant in question was however recruited via the standard process via CFR Ireland and in their capacity as lay CFR. Two healthcare professionals also participated in this research. Both were recruited via the mechanisms already described and in their capacity as lay CFR rather than healthcare professional. Their healthcare professional perspectives may have introduced bias; however, it is also possible that their inclusion reflects a phenomenon where healthcare professionals participate in varied capacities in lay CFR schemes. This interface of health professional and lay CFR was not explored in detail in this study and may warrant further consideration. It may have specific relevance in light of the complexity of the CFR role and formalising appropriate supports for CFRs in managing challenging clinical circumstances with psychosocial impacts.

Thematic analysis was selected as the methodological approach for this study based on its accessibility as a qualitative research approach and its flexibility in terms of theoretical framework.15 Such flexibility was considered necessary in order to facilitate a bottom-up inductive analysis of the participant data, in the context of a researcher who possessed an inherent disciplinary and ‘insider’ standpoint. It is possible that this perspective may have influenced the analysis. Ultimately, an ongoing reflexive process adopted and operationalised throughout this research project aimed to limit such biases in so far as were possible. Other steps taken to mitigate potential bias included the use of published guidelines in the development and implementation of the research, acknowledgement of the positive role of the researcher’s own experience of the topic and the collaboration with an experienced qualitative researcher throughout the research process.

Conclusion

In summary, our results suggest that the structures that underpin CFR are sophisticated, and the care provided is complex. This is a striking finding in the context of a voluntary and community enterprise. We offer figure 1 and its relevant subthemes as one potential model for lay CFR care in the community. This will need to be considered and further developed by all stakeholders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research team acknowledge the assistance of CFR Ireland and Dr David Menzies in planning and carrying out this research.

We would also like to specifically thank the CFRs who participated.

Footnotes

Contributors: TB conceived the study. All authors contributed to the design of the study. TB acquired the data. All authors interpreted and analysed the data. TB drafted the manuscript, which was critically revised for important intellectual content by all authors who approved the final version. TB is guarantor for the study.

Funding: This research was supported by an Irish College of General Practitioners research grant.

Disclaimer: The funder had no role in data collection, analysis or in the preparation of this manuscript.

Competing interests: TB and GB are general practitioners who participate voluntarily in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest community response and declare no other conflicts of interest. SG is an academic researcher with experience of health services research. She has no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was granted by the UCD Human Research Ethics committee Ref LS-17-42-Barry and participant informed consent was obtained prior to the commencement of data collection.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Atwood C, Eisenberg MS, Herlitz J, et al. Incidence of EMS-treated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Europe. Resuscitation 2005;67:75–80. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Valenzuela TD, Roe DJ, Cretin S, et al. Estimating effectiveness of cardiac arrest interventions: a logistic regression survival model. Circulation 1997;96:3308–13. 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barry T, Conroy N, Masterson S, et al. Community first responders for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;67 Art. No.: CD012764. DOI 10.1002/14651858.CD012764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hansen CM, Kragholm K, Granger CB, et al. The role of bystanders, first responders, and emergency medical service providers in timely defibrillation and related outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Results from a statewide registry. Resuscitation 2015;96:303–9. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith LM, Davidson PM, Halcomb EJ, et al. Can lay responder defibrillation programmes improve survival to hospital discharge following an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest? Aust Crit Care 2007;20:137–45. 10.1016/j.aucc.2007.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ringh M, Rosenqvist M, Hollenberg J, et al. Mobile-phone dispatch of laypersons for CPR in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2316–25. 10.1056/NEJMoa1406038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zijlstra JA, Stieglis R, Riedijk F, et al. Local lay rescuers with AEDs, alerted by text messages, contribute to early defibrillation in a Dutch out-of-hospital cardiac arrest dispatch system. Resuscitation 2014;85:1444–9. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Census CSO. Summary Results - Part 1. Dublin: Central Statistics Office, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9. OHCAR. Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest Register, Annual Report 2016. Galway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Masterson S, Wright P, O’Donnell C, et al. Urban and rural differences in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Ireland. Resuscitation 2015;91:42–7. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barry T, González A, Conroy N, et al. Mapping the potential of community first responders to increase cardiac arrest survival. Open Heart 2018;5:e000912 10.1136/openhrt-2018-000912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Robson C. Real world research: a resource for users of social research methods in applied settings. 3rd ed Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014;89:1245–51. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. London: SAGE, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lambiase PD. Reinforcing the Links in the Chain of Survival. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1118–20. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pijls RW, Nelemans PJ, Rahel BM, et al. A text message alert system for trained volunteers improves out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival. Resuscitation 2016;105:182–7. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Phung VH, Trueman I, Togher F, et al. Community first responders and responder schemes in the United Kingdom: systematic scoping review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2017;25:58 10.1186/s13049-017-0403-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Phung VH, Trueman I, Togher F, et al. Perceptions and experiences of community first responders on their role and relationships: qualitative interview study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2018;26:13 10.1186/s13049-018-0482-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Timmons S, Vernon-Evans A. Why do people volunteer for community first responder groups? Emerg Med J 2013;30:e13 10.1136/emermed-2011-200990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Davies E, Maybury B, Colquhoun M, et al. Public access defibrillation: psychological consequences in responders. Resuscitation 2008;77:201–6. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harrison-Paul R, Timmons S, van Schalkwyk WD. Training lay-people to use automatic external defibrillators: are all of their needs being met? Resuscitation 2006;71:80–8. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zijlstra JA, Beesems SG, De Haan RJ, et al. Psychological impact on dispatched local lay rescuers performing bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2015;92:115–21. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peberdy MA, Ottingham LV, Groh WJ, et al. Adverse events associated with lay emergency response programs: the public access defibrillation trial experience. Resuscitation 2006;70:59–65. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Braun V, Clarke V. (Mis)conceptualising themes, thematic analysis, and other problems with Fugard and Potts’ (2015) sample-size tool for thematic analysis. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2016;19:739–43. 10.1080/13645579.2016.1195588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.