Abstract

Background

Pregnancy is an opportunity for health providers to support women to stop smoking.

Objectives

Identify the pooled prevalence for health providers in providing components of smoking cessation care to women who smoke during pregnancy.

Design

A systematic review synthesising original articles that reported on (1) prevalence of health providers’ performing the 5As (‘Ask’, ‘Advise’, ‘Assess’, ‘Assist’, ‘Arrange’), prescribing nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and (2) factors associated with smoking cessation care.

Data sources

MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycINFO databases searched using ‘smoking’, ‘pregnancy’ and ‘health provider practices’.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Studies included any design except interventions (self-report, audit, observed consultations and women’s reports), in English, with no date restriction, up to June 2017.

Participants

Health providers of any profession.

Data extraction, appraisal and analysis

Data were extracted, then appraised with the Hawker tool. Meta-analyses pooled percentages for performing each of the 5As and prescribing NRT, using, for example, ‘often/always’ and ‘always/all’. Meta-regressions were performed of 5As for ‘often/always’.

Results

Of 3933 papers, 54 were included (n=29 225 participants): 33 for meta-analysis. Health providers included general practitioners, obstetricians, midwives and others from 10 countries. Pooled percentages of studies reporting practices ‘often/always’ were: ‘Ask’ (n=9) 91.6% (95% CI 88.2% to 95%); ‘Advise’ (n=7) 90% (95% CI 72.5% to 99.3%), ‘Assess’ (n=3) 79.2% (95% CI 76.5% to 81.8%), ‘Assist (cessation support)’ (n=5) 59.1% (95% CI 56% to 62.2%), ‘Arrange (referral)’ (n=6) 33.3% (95% CI 20.4% to 46.2%) and ‘prescribing NRT’ (n=6) 25.4% (95% CI 12.8% to 38%). Heterogeneity (I2) was 95.9%–99.1%. Meta-regressions for ‘Arrange’ were significant for year (p=0.013) and country (p=0.037).

Conclusions

Health providers ‘Ask’, ‘Advise’ and ‘Assess’ most pregnant women about smoking. ‘Assist’, ‘Arrange’ and ‘prescribing NRT’ are reported at lower rates: strategies to improve these should be considered.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42015029989.

Keywords: smoking, healthcare providers, smoking cessation, maternal health, pregnancy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Comprehensive meta-analysis and meta-regression of health providers implementation of the ‘Ask’, ‘Advise’, ‘Assess’, ‘Assist’, ‘Arrange’ combining like measures for smoking cessation care.

Fifty-four studies from seven high-income and three low-to-middle-income countries include disciplines of medicine, nursing and allied health.

High heterogeneity in the meta-analyses was unexplained by the meta-regressions, except for ‘Arrange referral-often/always’ which was related to year and country.

Quality ratings of some papers were poor—findings from these studies may be less reliable.

Review aids in determining which components of smoking cessation care are less reliably implemented in pregnancy.

Introduction

Smoking during pregnancy carries high risks for mother and child, including obstetric complications for the mother,1 and for the baby, premature birth, growth restriction, low birth weight, stillbirth and congenital defects.1 2 Longer term effects on the child include respiratory illnesses, learning and behavioural problems, and increased risks of chronic diseases,1 2 and of taking up smoking in adolescence.3

Smoking during pregnancy remains a prevalent behaviour in many countries, with estimated smoking prevalence rates ranging from 0.2% to 38.4%.4 Pregnancy is a time when women are more likely to be motivated to stop smoking.5 However, disadvantaged women, including women from minority and indigenous populations where there is a high prevalence of community smoking, also smoke at higher rates and are less likely to try to stop smoking, or succeed than more advantaged women among whom smoking prevalence is lower.6 7 Also, less likely to stop smoking are women who are: of low socioeconomic status,6 multiparous,6 adolescents,8 partnered by smokers,6 and those experiencing: alcohol or substance use,8 depression,9 life stressors10 11 or intimate partner violence.12 Women frequently reduce tobacco consumption when discovering they are pregnant,11 13 indicating a consciousness about the risks, but may be less likely to abstain than non-pregnant women.14 Pregnant women report a lack of support for smoking cessation, and that health providers (HPs) consider cutting down to be acceptable.15 16

HPs in primary care have a critical role to offer advice and support women to stop smoking during pregnancy.17 Ideally smoking cessation care (SCC) includes counselling and pharmacotherapy—most successful when combined.17 18 In pregnancy, the effective use of pharmacotherapy is less certain, and clinical guidelines vary across and within different countries.17 In pregnancy, only nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is recommended, but not consistently advised for use in pregnancy in all countries,17 19 for example, NRT is not advised in the USA for use in pregnancy,20 but it is more routinely prescribed in the UK.21 Clinical guidelines in the UK, Australia, New Zealand (NZ) and Canada recommend that a woman should initially endeavour to quit without medication, but if she cannot, NRT can be prescribed.17 22–25

The 5As (‘Ask (about smoking)’, ‘Advise (to quit)’, ‘Assess (motivation and/or dependence)’, ‘Assist (with cessation)’ and ‘Arrange (follow-up or referral)’) has been adopted in many countries as a strategy for HPs to deliver all the important components of SCC.26 Several studies have examined the performance of the 5As in pregnancy. Two reviews summarised the literature. Okoli et al’s integrative review reported on HP performance of components of the 5As. While authors reported more than 50% of HPs ask and advise about smoking, and less than 50% Assess, Assist or Arrange (referral or follow-up), it is unclear how these estimates were calculated. This is an important limitation considering the variable ways studies collect data and report them.27 Baxter et al’s qualitative systematic review, on the factors that influenced uptake of interventions by pregnant women, included studies on HP and women’s reports of their receipt of SCC, and noted variation between HPs for recording smoking status and advice.28 As neither review included a meta-analysis, it is timely and important from the point of view of rigour to have a definitive evaluation of HP practices, and furthermore to accurately inform recommendations to guide strategies to improve SCC. An urgent need for research to increase the uptake of smoking cessation interventions, and improve quit rates in pregnant women who smoke has been identified by Siddiqi and Mdege.29

The objective of this systematic review was to summarise published empirical research of eligible studies from a range of HPs who consult with pregnant women who smoke, and synthesise findings with meta-analyses where feasible. The primary aim was to determine the prevalence of the components of SCC that were being practised, including the 5As, prescribing NRT and related behavioural change techniques (BCTs—observable and replicable components designed to change behaviour),30 thus determine which aspects of SCC need improvement. A second aim was to examine which factors were associated with delivery of the 5As, and NRT prescribing, that is, HP types, country, year and pregnant women in high-risk populations. We also examined data about knowledge and attitudes of the HPs to inform their practices.

Methods

Data were identified by searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycINFO, and reference lists from relevant articles. Where possible, search terms were matched to MeSH or database specific subject headings, and used as keywords. Search terms included (see online supplementary table 1): pregnancy (eg, perinatal care, mother), smoking (eg, nicotine dependence, smoking cessation), health professional (eg, general practitioner (GP), midwife) and attitudes or practices (eg, capacity, belief). Searches were performed in September 2015; additional studies included until June 2017.

bmjopen-2018-026037supp001.pdf (495KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria: peer-reviewed full papers on SCC to pregnant smokers by any HP in any setting, restricted to English language, with no date restrictions. Quantitative studies and/or quantitative data from mixed-methods studies with any study design were included, comprising self-reported provision of SCC by HPs, reported receipt of SCC by pregnant women, or other indicators, for example, chart audit or audio recordings of consultations. For this review, SCC was based on the 5As: asking about smoking, advising about quitting, assessing motivation to stop smoking or nicotine dependence, assisting to quit and arranging follow-up or referral.26 In addition, we included papers reporting HP knowledge, attitudes and other practices, for example, advising about relapse and smoke-free homes, discussing psychosocial contexts of smoking, involving family members or partners, prescribing NRT and other BCTs (eg, setting a quit date, making a quit plan, providing resources and self-help materials, aiding social support, encouraging smoke-free environments and monitoring carbon monoxide readings).31 32 Exclusion criteria: intervention studies and studies in non-peer-reviewed literature; studies on preconceptual and postnatal care. Additionally, 10 papers that did not have a main focus on the review topic and/or reported minimal data about the topic such as one line or one data item in a full paper were excluded (list available from authors on request). We used the MOOSE checklist when writing our report.33

Two researchers (LT—behavioural scientist, YBZ—physician) independently screened titles, abstracts, and then full papers and applied the inclusion criteria to determine eligibility. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus, with a third researcher (GSG) acting as adjudicator, when agreement was not reached. Studies that met all criteria were retained for full review. One researcher completed data extraction (LS) with a second (YBZ) extracting 20% of articles, then results compared. A summary table (see online supplementary table 2) was developed from this data (GRG and GSG). The characteristics of each study were examined including aims, setting, country, sample characteristics, study focus (HP or women), HP type, study design and method, measures, extracted results for each of the 5As, prescription of NRT, and whether the study addressed the provision of BCTs, and if so a description of the BCTs (eg, setting a quit date, increasing self-efficacy, monitoring carbon monoxide reading, validating abstinence).

As the studies overall were of all types of design, a quality assessment of the quantitative and mixed studies was carried out using Hawker et al’s tool for reviewing disparate data systematically.34 This was chosen in the absence on any consensus on the best tool, as we were including quantitative and mixed-method studies in the review. LS rated all studies using the tool (20% double rated by YBZ). Studies were included irrespective of quality.

Quantitative data were presented as percentages and counts were possible, and meta-analyses made for estimates of each of the 5As of SCC provision and prescribing NRT. A narrative analysis summarises other studies or outcomes, including BCTs where reported. For each outcome measure, we looked at the specific measurements across studies to determine whether it was clinically appropriate to group them together, that is, Ask, Advise, Assess (motivation to quit, nicotine dependence), assist (cessation support, quit date, quit plan, prescribe NRT), Arrange (follow up, referral). To achieve this, we considered both the data collection method (cross-sectional survey; audit of patients’ medical records; audio recording of consultation; women’s report through survey or interview) and the measure itself that was used (eg, Likert scale or a dichotomous yes/no response and so forth). General principles applied were as followed (explained in more detail in online supplementary text 1):

‘Often/always’ included survey measures reflecting asking ‘often’ and ‘always’, ‘usually and always’; and/or ‘most of the time’ and ‘all of the time’). The combined answers in Likert scales were dichotomised for analysis.

‘Always/all’ included in this analysis was the proportion of HPs answering ‘always’ or ‘all of the time’, if a Likert scale was used, or the proportion answering ‘yes’ if a dichotomous question was used: either asking ‘do you ask all of your patients?’ or ‘do you ask your patients always?’ Answers reporting on ‘Asking’ more than 75% of their patients were considered as ‘yes’ for these analyses.

‘Yes’ where a survey asked the HP a dichotomous question, for example, ‘do you advise? Yes/no’ were grouped separately as ‘advise—yes’.

Papers describing women’s reports were analysed separately from those describing HP reports.

All statistical analyses were programmed using Stata V.13.1 (StataCorp LP). Meta-analyses were performed to examine the performance of each of the 5As, including prescribing NRT, as above. Stata program Metaprop was used to pool dichotomised responses for each of the 5As. If more than five studies were pooled, random-effects modelling (DerSimonian and Laird’s method) was used to account for differences in underlying estimates due to study population and design; heterogeneity (I2) was measured for each reporting type. If the number of studies was low (≤5), fixed-effects modelling was used as the between-studies variance (τ2), and therefore, the mean of the underlying random distribution cannot be estimated with precision; heterogeneity is not presented.35 Where required, in order to include studies where the per cent reporting the outcome was 100%, the Freeman-Tukey Double Arcsine Transformation method was used to stabilise the variances prior to pooling. Pooled estimates for study outcomes were split by response, and also by HP type. Significance was set as α=0.05 a priori.

For the ‘often/always’ responses to Ask, Advise, Assist, Arrange, including prescribing NRT, meta-regression (Stata program Metareg) was used to examine whether some of the heterogeneity seen in the proportions reported for each study could be explained by HP type (eg, midwife, GPs, obstetricians (OBS) or mixed groups of HPs), high-risk population versus not (eg, women in low socioeconomic groups, indigenous women or with mental health diagnoses), country (USA, Europe, Australia/NZ or other) or year of publication (1990–2017). P value, changes in heterogeneity (I2 residual), changes in between study variance (τ2) and proportion of between-study variance explained by predictor (adjusted R2) were reported. For year, the linearity of proportion over time was examined, and if a non-linear trend was seen then the meta-regression was not performed. Meta-regressions for the other meta-analyses were not performed.

An analysis of agreement of quality-rating coders was performed. Weighted kappa (ordinal multirater—quadratic weighted Kappa) was used to compare the rating of 9 quality study criteria for 15 studies; each criterion was scored on a 5-point scale (very poor, poor, fair, good and very good). Mean (SD) ratings were calculated for each criterion for each rater. Kappa and weighted kappa estimates were interpreted using cut-off criteria specified by Altman.36 Strength of agreement was <0.20 poor; 0.21–0.40 fair; 0.41–0.60 moderate; 0.61–0.80 good; 0.81–1.00 very good.

Patient and public involvement

As a systematic review, we did not directly involve any patients or public in the study. However, the review was informed by patient and HP needs. Participants from previous studies reported to us that they were not receiving comprehensive SCC during pregnancy from their HPs,16 nor were HPs in a previous study reporting they delivered comprehensive SCC.37 This review was responsive to global knowledge about the receipt and delivery of SCC in pregnancy being a gap in the literature.

Results

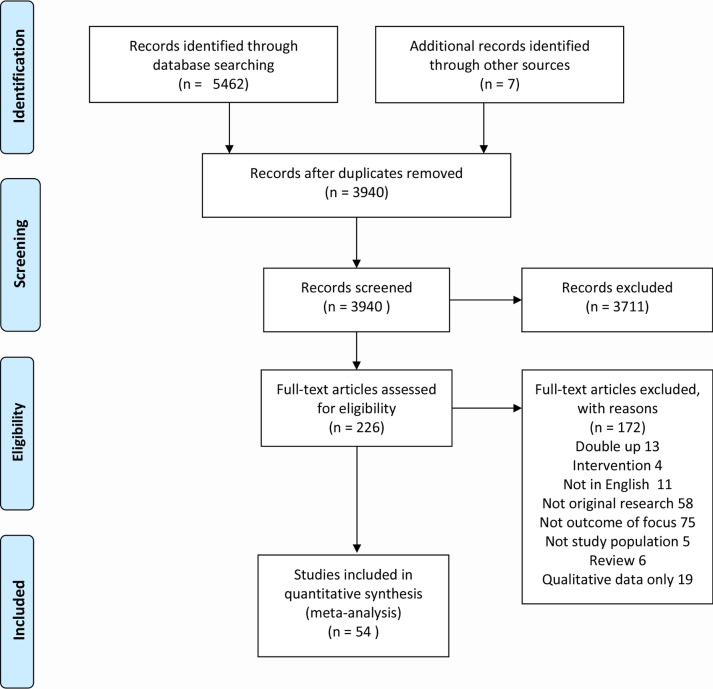

Of the 3933 studies found, 54 papers met the inclusion criteria for quantitative review. See Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart for included studies (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of included studies.98

A total of 54 studies were included in this analysis.37–90 Study details, including author, country, study focus (HP, women or both), population and risk category (high/low), study aims, inclusion of 5As and summary of results, are presented in online supplementary table 2. Of these studies, approximately 90% were quantitative (n=49),37–43 45 48–64 66–75 77–90 and approximately 10% (n=5) used mixed methods, containing both quantitative and qualitative aspects.44 46 47 65 76 The included studies used the following study methods: survey (n=48),37–45 48–62 64–67 69–81 84–90 audio recordings (n=2),46 47 audit (n=2),82 83 audit with interview (n=1)63 and observational (n=1).68

Study location included seven high-income countries (USA,38 45 49 54 57–59 61 65 71 78 79 86 UK,44 48 52 60 74 Australia,37 51 75 76 87 90 Germany,81 84 Switzerland,66 NZ,55 56 80 France,46 and three low-to-middle-income countries (Jordan, Argentina and Uruguay).28 32 59

Included studies focused on either HPs (n=39, 72%),37–39 41 43 44 47–55 57–61 65 66 68–73 75 78–81 83 84 87–90 pregnant women (n=12, 22%)40 42 45 56 62 63 67 74 76 82 85 86 or both HPs and pregnant women (n=3, 6%).46 64 77 Studies encompassing HPs included obstetricians and gynaecologists (OBS) (n=9, 21%),39 49 53 54 57 65 71 73 79 midwives (n=7, 17%),38 41 51 52 64 72 84 GPs (n=3, 7%),60 61 68 multiple professions (eg, OBS, GPs, nurses, healthcare assistants; n=21, 50%),37 43 44 46–48 50 55 58 59 66 69 70 75 77 79–81 87 89 90 or did not report the profession (n=1, 2%).83

Out of the 54 papers, information on 5As, ie, Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist and Arrange (follow-up/referral) was reported by approximately 68%, 70%, 28%, 63% and 54% of studies, respectively. Few studies addressed all of the 5As combined (n=12, 22%). These reported that HPs rarely addressed all of the 5As, for example, only 19.6% of respondents in Zeev et al’s study of GPs and OBS performed all of the 5As ‘often/always’.37

Only four studies (7%) addressed the provision of other BCTs in pregnancy. In one study, 31% of OBS advised women to set a quit date39; in a second study 29% of midwives suggesting quitting with an acquaintance52; 97% of women in a third sample reported they had not had their exhaled carbon monoxide tested,56 and a fourth study reported which of the clinics used open-ended questions and problem solving.89 Additionally, some studies (n=12, 22%) obtained information on or addressed a woman’s psychosocial context for smoking, for example, family or partner’s smoking status or involvement in quitting, a woman’s social support or her living environment, for example, a smoke-free home or vehicle (n=3, 6%). Information regarding the use of resources was addressed in 20 studies (37%), that is, providing pamphlets or recommending an online programme. Advice about relapse was rarely addressed in the included literature (n=3, 6%); for example, in one of the studies midwives reported they discussed with women how to avoid relapse.52

Twenty-nine of the 54 papers addressed NRT in some capacity. These included knowledge and training, attitudes to NRT and prescribing of NRT. Papers addressing knowledge, attitudes and training in general (n=14, 26%) also reported on HP knowledge about whether NRT can be used in pregnancy, and HP confidence about their smoking cessation knowledge, awareness of smoking cessation guidelines, knowledge about the consequences of smoking for expectant mothers and risks to their baby. The majority of HPs believed maternal smoking to be harmful to the fetus and/or the woman, with reports ranging from 90% to 100%. General knowledge about smoking in pregnancy varied (eg, in Bonollo et al43 only 44%–52% of US HPs of various types, had correct knowledge). In Mejia et al’s study, 75% of Argentinan physicians believed that it was safe to smoke up to six cigarettes when pregnant.69

In addition, the above group of studies included aspects of smoking cessation training (ie, whether training had been offered, engaged in and if more training was needed). In general, HPs reported that they had received limited training on SCC in pregnancy, and identified that they required more training.

Papers including information on NRT prescribing (n=14, 26%) reported on the frequency of considering to prescribe NRT, the frequency of recommendation of NRT, frequency of prescribing NRT, percentage of NRT scripts filled by women, percentage following Food and Drug Administration (FDA) NRT prescription recommendations and the different NRT types prescribed (eg, patches, gum or inhalators). Overall findings suggested that HPs more often than not chose to not prescribe NRT to pregnant women who smoke, this was also supported by the meta-analysis below.

Attitudes and knowledge were associated with HP practices. In one Australian study, higher levels of knowledge about NRT were associated with greater likelihood of assessing women’s smoking status.75 In another US study, OBS who perceived NRT as safe to use in pregnancy were 20 times more likely to prescribe NRT.78 An Australian study determined that HP optimism, and confidence in counselling and/or prescribing NRT, and having sufficient time and resources were associated with a higher performance of all the 5As.37

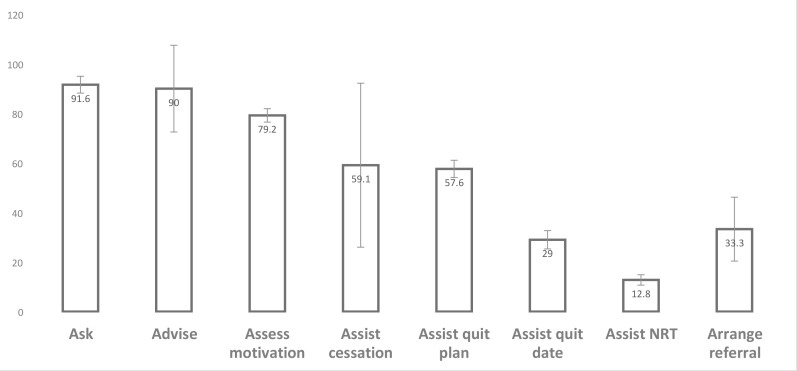

Thirty-three studies were suitable for meta-analysis.38 39 42 44 45 48 49 51 52 54–58 60 61 65 66 69 71 74–76 78 80 81 84 87 90 91 Seventeen meta-analyses were performed and associated forest plots constructed (see online supplementary figures 1–17). Figure 2 provides a visual comparison for pooled percentages of selected categories of ‘often/always’.

Figure 2.

Comparison of pooled percentages of selected categories of ‘often/always’. NRT, nicotine replacement therapy.

Overall the performance of ‘Ask—often/always’ (n=9) was 91.6% (95% CI 88.2% to 95%). Percentages for ‘Ask—‘always/all’ (n=11) was similar at 91.5% (95% CI 85% to 96.3%). Percentages for ‘Ask—yes’ (n=4, all by women’s report) was slightly higher at 93.6% (95% CI 92.6% to 94.6%).

The performance of ‘Advise—often/always’ (n=7) was 90% overall (95% CI 72.5% to 99.3%). Percentages for ‘Advise—always/all’ (n=6) was 86.4% overall (95% CI 79.6% to 93.3%). Percentages for ‘Advise—yes’ (HP report) (n=4) was much lower at 58.1% overall (95% CI 55.9% to 60.4%). Percentages for ‘Advise—women’s report yes’ (n=4) was similar at 53.6% overall (95% CI 52.6% to 54.6%). Percentages for ‘Assess motivation to quit – often/always’ (n=3) was 79.2% overall (95% CI 76.5% to 81.8%).

Overall 34 manuscripts included a question about assisting. Some were generally asked about assisting the patient to quit, others specified a method of assisting such as counselling, setting a quit date, making a quit plan and prescribing NRT. Those in the meta-analysis were as follows: ‘Assist cessation support—often/always’ (n=5) was 59.1% (95% CI 56% to 62.2%); ‘Assist counselling—yes’ (n=5) was higher at 80.7% (95% CI 79% to 82.5%); ‘Assist quit plan—often/always’ (n=2) was 57.6% (95% CI 54.1% to 61.1%); ‘Assist quit date—often/always’ (n=3) was low at 29% (95% CI 25.3% to 32.7%); ‘Assist—women’s report yes’ (n=4) was the lowest at 26.8% (95% CI 25.3% to 28.3%). The performance of ‘Arrange referral—often/always’ (n=6) was 33.3% overall (95% CI 20.4% to 46.2%). There were no analysable data on women’s report for ‘Arrange’.

‘Prescribing NRT—yes’ was 25.4% (n=6) overall (95% CI 12.8% to 38%). ‘Prescribing NRT—often/always’ (n=4), however, was very low at 12.8% overall (95% CI 10.7% to 15%). The performance of ‘Prescribing NRT—always’ (n=4) was the lowest at 6.2% overall (95% CI 4.9% to 7.4%). There were no analysable data on women’s report of having been prescribed NRT. All of the studies in the meta-analysis for ‘Prescribing NRT—yes’ were from the USA (see online supplementary figure 17).

High heterogeneity (I2=95.9%–99.1%) was seen for: ‘Ask—often/always’; ‘Ask—always’; ‘Advise—often/always’; ‘NRT prescription’; ‘Arrange referral—often/always’; thus indicating considerable diversity in study outcomes, methodology or populations. A fixed-effects model was used for the following outcomes due to low number of studies, and heterogeneity was not measured: ‘Ask—women’s report yes’; ‘Advise—yes’; ‘Assess motivation to quit—often/always’; all the ‘Assist’ categories; ‘NRT Prescription—always’, ‘NRT Prescription—often/always’.

Table 1 displays the results of the meta-regression of the ‘often/always’ categories of ‘Ask’, ‘Advise’, ‘Arrange’ and ‘Prescribing NRT’ from the meta-analysis. ‘Assist’ only had five studies, so the meta-regression was not performed. For nearly all of the measures, none of the predictors examined significantly explained the heterogeneity of the proportions for the studies. For ‘Arrange referral—often/always’, country was found to explain some of the differences in proportion of HPs providing this type of SCC; with Australian and NZ studies having significantly higher proportions of HPs reporting ‘Arrange referral—often/always’ than US studies (on average). Year was also found to explain some of the differences in proportion with later years having higher proportions of HP reporting this ‘Arrange referral—often or always’ (on average).

Table 1.

Meta-regression analysis of HP practices performed ‘often/always’

| Predictors | Ask | Advise | Assist | Arrange | NRT |

| N studies | 9 | 7 | 5* | 6 | 6 |

| No predictors | |||||

| I2 resid | 96% | 91.9% | 95.9% | 97% | |

| τ2 | 0.008 | 0.0304 | 0.019 | 0.017 | |

| Provider type | |||||

| P value | 0.18 | 0.487 | 0.898 | 0.304 | |

| adj r2 | 24.7% | −1.5% | −57.6% | 26.4% | |

| I2 resid | 95.6% | 87.7% | 97.4% | 94.8% | |

| τ2 | 0.006 | 0.031 | 0.029 | 0.013 | |

| High risk | |||||

| P value | 0.909 | † | 0.571 | † | |

| adj r2 | −14.4% | −13.4% | |||

| I2 resid | 96.4% | 96.7% | |||

| τ2 | 0.009 | 0.021 | |||

| Country | |||||

| P value | 0.845 | 0.252 | 0.037 | 0.903 | |

| adj r2 | −42.2% | 27.6% | 66.9% | −25.2% | |

| I2 resid | 96.5% | 89.4% | 84.5% | 97.6% | |

| τ2 | 0.012 | 0.022 | 0.006 | 0.021 | |

| Year | |||||

| P value | ‡ | ‡ | 0.013 | ‡ | |

| adj r2 | 81.9% | ||||

| I2 resid | 73.9% | ||||

| τ2 resid | 0.003 |

*Too few studies, I2 and τ2 not available.

†No high-risk populations.

‡Non-linear, model not performed.

HP, health provider; NRT, nicotine replacement therapy.

Table 2 shows the quality rating with the Hawker et al tool,34 for included studies. Over 70% of the studies had some aspects at least that were rated as good, and 20 out of 53 (37.7%) studies that were rated had at least 5 ‘good’ categories out of the 9 available options. Common flaws were lack of clarity about aims, sampling processes not detailed, ethics processes not described, and no suggestions made for further research.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of 54 included studies

| Author | Abstract and title | Intro and aims | Method and data | Sampling | Data analysis | Ethics and bias | Results | Transferability | Implications and usefulness |

| Abatemarco et al38 | Good | Good | Fair | Good | Fair | Fair | Poor | Good | Good |

| Amarin39 | Poor | Fair | Poor | Poor | Poor | Poor | Poor | Poor | Fair |

| Bakker et al40 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Bar-Zeev et al37 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair | Good |

| Beenstock et al41 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Good |

| Berrueta et al42 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair | Fair | Good | Good | Good |

| Bonollo et al43 | Good | Good | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Bull and Whitehead44 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Good | Good | Fair | Good |

| Castrucci et al45 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Very poor | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Chang et al46 | Good | Good | Good | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Chang et al47 | Fair | Good | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Fair | Fair | Good |

| Clasper and White48 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Coleman-Cowger et al49 | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Fair | Very poor | Fair | Fair | Good |

| Condliffe et al50 | Good | Fair | Good | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Cooke et al51 | Good | Fair | Fair | Good | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Good |

| Cooke et al90 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Eiser et al52 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| England et al53 | Good | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Floyd et al54 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair | Fair | Poor | Fair |

| Glover et al55 | Fair | Fair | Poor | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Grangé et al56 | Poor | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Grimley et al57 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Fair | Good |

| Hartmann et al58 | Good | Good | Good | Fair | Fair | Good | Good | Fair | Fair |

| Helwig et al59 | Good | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Herbert et al60 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Hickner et al61 | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Hoekzema et al62 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Fair | Fair | Good | Good | Fair |

| Howard et al63 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Fair | Good |

| Jones64 | Good | Good | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Jordan et al65 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair | Good |

| Lemola et al66 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Good |

| Mabbutt et al67 | Good | Good | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair | Good | Poor | Fair |

| McEwen et al68 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mejia et al69 | Good | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair | Good |

| Moran et al70 | Fair | Good | Good | Good | Good | Poor | Good | Good | Good |

| Mullen et al71 | Fair | Good | Fair | Fair | Good | Poor | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Murphy et al72 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair | Good | Fair | Good | Good |

| Oncken et al73 | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Good | Poor | Good | Good | Fair |

| Owen and McNeill74 | Poor | Fair | Poor | Very poor | Poor | Poor | Poor | Fair | Fair |

| Passey et al75 | Good | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Good |

| Passey and Sanson-Fisher76 | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Passey et al77 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair | Good | Fair | Good |

| Price et al78 | Good | Fair | Good | Fair | Good | Poor | Good | Fair | Good |

| Price et al79 | Good | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Pullon et al80 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Poor | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Röske et al81 | Good | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Fair |

| Solberg et al82 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Tappin et al83 | Fair | Fair | Fair | Good | Poor | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Thyrian et al84 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Tong et al85 | Good | Good | Fair | Good | Fair | Poor | Fair | Good | Fair |

| Tran et al86 | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Good |

| Tzelepis et al87 | Good | Fair | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Walsh et al88 | Good | Fair | Good | Fair | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair | Fair |

| Zapka et al89 | Good | Fair | Good | Fair | Good | Fair | Good | Fair | Fair |

NA, not applicable as was a letter to the editor.

Table 3 shows the quality ratings of the studies, and level of agreement from using the Hawker tool,34 for the 15 papers that were rated independently by two raters. Coder agreement varied from poor for two criteria, fair for four of the criteria and moderate for three criteria.

Table 3.

Findings from agreement of quality rating analysis of coders using the Hawker tool

| Study criteria | Mean rating (SD) 1 (very poor) to 4 (good) |

Agreement | ||

| Rater 1 | Rater 2 | Weighted kappa (95% CI) | Agreement | |

| Abstract and title | 2.4 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.6) | 0.13 (−0.41 to 0.68) | Poor |

| Intro and aims | 2.3 (0.5) | 2.1 (0.3) | 0.25 (−0.17 to 0.67)* | Fair |

| Method and data | 2.2 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.6) | −0.15 (−0.74 to 0.43) | Poor |

| Sampling | 2.1 (0.8) | 2.3 (0.6) | 0.43 (0.10 to 0.76) | Moderate |

| Data analysis | 2.1 (0.6) | 2.1 (0.5) | 0.51 (0.03 to 0.99) | Moderate |

| Ethics and bias | 1.9 (0.8) | 1.9 (1.0) | 0.38 (0.13 to 0.63) | Fair |

| Results | 2.3 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.5) | 0.26 (−0.11 to 0.62) | Fair |

| Transferability | 2.2 (0.4) | 2.3 (0.6) | 0.21 (−0.19 to 0.61) | Fair |

| Implications and usefulness | 2.4 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.6) | 0.58 (0.18 to 0.98) | Moderate |

*Only two levels, therefore Kappa rather than weighted Kappa used.

Discussion

This systematic review of 54 studies from 10 countries on a range of HPs who consult with pregnant women who smoke. Thirty-three studies were suitable for meta-analyses for at least one outcome measure. Studies displayed considerable variation in the way they assessed HP provision of each of the 5As. Commonly surveys employed Likert scales that were recategorised as ‘often or always’ or questions forcing a ‘yes/no’ option. We pragmatically transformed outcome measures so they could be combined for meta-analysis, over the 5As and their subcategories, resulting in small numbers of studies in each forest plot, which means that interpretations should be cautious. We acknowledge that there was no ideal way to combine these measures. Conceptually, using a scale to quantify responses is quite different from a ‘yes’ option: the latter may be an option chosen by respondent whether they perform the practice at an frequency from occasionally to always (ie, not at all quantified)—therefore we did not combine ‘often/always’ with ‘yes/no’ study measures.

The primary aim to determine the prevalence of the components of SCC that were being practised by a range of HPs. The review demonstrated several aspects of SCC that could be improved for pregnant women, including those seen in primary care settings. The highest rates were for Ask and Advise and Assess. Assist and Arrange were consistently lower. Our secondary aim to examine whether SCC differed between different HP types, for pregnant women in high-risk populations, by country, and by year was achieved by meta-regressions of studies reporting practices ‘often/always’. Only ‘Arrange referral’ had a significant result, indicating that year and country could explain some of the heterogeneity, and perhaps indicating an increased awareness of referral options in later years, or in Australia and NZ. The 21 studies not included in the meta-analysis revealed few comparable quantitative studies on HP knowledge, attitudes and the lesser reported practices of BCTs, and the implementation of all components of the 5As together. On the whole HP knowledge base might be insufficient about NRT. Poor understanding about the safety or efficacy of NRT in pregnancy compared with continued smoking may lead to underprescribing of NRT as a stop smoking aid, however, this is likely to be context sensitive as not all countries recommend the use of NRT and clinical guidelines vary across time and even within the same country.17 However, all of the studies in the meta-analysis of NRT were from the USA, and considerable variation for prescribing NRT is seen within that one country. Access to HP training for SCC was reported as being limited, and HPs indicated they required more training.

The strength of this study is that, as far as we are aware, it is the broadest and most rigorous systematic review of HP performance of the 5As in pregnancy, including seven high-income and three low-to-middle-income countries and the only review, to our knowledge, to perform a meta-analysis and meta-regression. We took care to combine outcome measures with like measures, for each of the 5As, wherever possible. Multiple meta-analyses were performed, for each combined measure. The high heterogeneity suggests a cautious interpretation of the results. The review was limited by not being able to determine the cause for the high heterogeneity in the meta-analyses by our meta-regression, except for ‘Arrange referral-often/always’ which was related to year and country. We recognise that differing clinical guidelines may have impacted the provision of NRT in pregnancy in some countries. In particular, NRT is not recommended for pregnancy in the USA. Additionally, while most countries do use the 5As, there are variations, such as ABC (Ask, Brief Advice, Cessation) in NZ and Ask, Advise, Action in the UK. These have in common the first 2As, and then a variation to shorten the mnemonic or practice. This variation may be a limitation to this study. The review was also limited by publications only being included up to June 2017.

Where the number of studies was low (≤5), fixed-effects modelling was used because the between-studies variance (τ2), and therefore, the mean of the underlying random distribution cannot be estimated with precision; heterogeneity is also not presented in these cases. We suggest that these results are interpreted with caution, and consideration be given to the degree of overlap in the study specific CIs. The quality rating revealed aspects of some papers were poor; findings from these studies may be less reliable. However, unresolved discrepancies between the raters indicate a circumspect interpretation.

Two other reviews examined the provision by HP of SCC for pregnant women. Okoli et al’s non-systematic review included 28 studies from 6 high-income countries (USA, Australia, UK, Germany, Canada and the Netherlands).27 The review reported that few HPs working with pregnant women use all the components of the 5As. Although more than 50% of HPs in the review asked women about their smoking status and advised pregnant smokers to quit, fewer than 50% assessed motivation, assisted smoking cessation, or arranged follow-up or referrals. Our review highlighted the diversity of the ways different studies surveyed HPs about their use of the 5As, but it is unclear from the Okoli review how these estimates were made. Instead a range was reported for each of the 5As, (eg, ‘Ask’ 73%–100%; ‘Assess’ readiness or willingness to make a quit attempt 42%–81%) without the reader being able to determine which studies used Likert scales, if measures were recategorised, or a dichotomous yes/no employed. Baxter et al’s systematic review included 23 papers from 6 high-income countries, 1 middle-income country (UK, France, Sweden, USA, Australia, NZ, South Africa) and one multination study, in a qualitative synthesis.28 Similarly, although Baxter’s review reports percentages of HP or women giving or receiving different aspects of the 5As, they do not describe how these questions were asked.28

The low rates of reported implementation of components of the 5As may be related to barriers at several levels. Okoli et al’s review suggests several important provider-specific, patient-specific and system or organisational barriers hindering the provision of SCC by HP.27 Provider-specific barriers centred around HP self-efficacy or perceived ability to provide SCC to pregnant smokers, namely low knowledge, low confidence for counselling and use of NRT, the perception that as HPs they could not influence the patient’s smoking behaviour, or that SCC was not their role. In the studies in our review, HP practices also related to HP knowledge and attitudes (optimism and confidence). Patient-level barriers included HP perceptions that pregnant smokers were not interested in quitting, had stressful lives, and HPs not wanting to jeopardise their relationship with the pregnant patient by raising smoking as an issue. System-level barriers included lack of time, resources, training and protocols, similarly described in our review. Baxter et al’s review also reports barriers to providing SCC: discussing smoking cessation depended on whether HPs were able to broach the subject, staff confidence and perception of effectiveness, manner of communication, whether follow-up occurred, time and resource constraints, and service protocols.28

One of the included Australian studies explained some of the factors that may impinge on the quality of SCC for pregnant women. Zeev et al analysed the factors associated with performance of the 5As, and provision of NRT in Australian medical practitioners.37 In a national study of 378 GPs and OBS, ‘internal influences’ (including HP confidence for counselling and prescribing NRT, optimism, sufficient time and resources) were associated with a higher likelihood of performing the 5As, whereas ‘external influences’ (ie, workplace routines, doctor–patient relationship, comfort raising the issue, perceived priority) were associated with performing the shorter version of Ask, Advise, Refer (AAR).37 92 93 Furthermore, being an OBS compared with being a GP, low confidence, and uncertainty about safety of NRT, were associated with lower odds of prescribing NRT.91

Our objective to determine which aspects of SCC for pregnant women could need improvement, revealed on the whole that ‘Assist’ and Arrange’ were less performed. Assisting pregnant smokers to quit is a vital priority. Unless there are high-quality specialised services to refer pregnant smokers to, it is insufficient for HPs to raise the issue, advice and assess, without going further to actually assist a quit attempt, and as a duty of care arrange follow-up or referral. Psychosocial support coupled with NRT (if needed, available and approved) may give pregnant women the best chance of quitting.17 94 Various implementation strategies could be considered to improve SCC delivery to pregnant women, which may include HP education and training, promotion of clinical practice guidelines, audit and feedback, reminders, opinion leaders, incentives or supervision.95 Training was reported as an educational need by the HPs in the studies, and worthy of consideration. Training should most urgently focus on the elements of the 5As that are seldom performed, taking into account country-specific needs and guidelines. Training should provide actual skills to HPs in how to assist smokers to quit, and give opportunities to practise and receive feedback on their performance. Evidence-based updates on the use of NRT in pregnancy may be warranted especially if professional college guidelines are not up to date, with a caution about jurisdictions that may deter prescribing or access.17

Providing access to resources, such as educational and training materials for HPs, evidence-based and culturally appropriate patient information sources and affordable NRT, will demand changes to policy in some settings and countries. Time is a perennial problem for HPs, however, changes in practice protocols, and a whole-of-service approach, could support pregnant women to receive the time investment warranted by such an important issue for their own and their baby’s health. Additionally, policy changes to provide accessible and culturally appropriate referral options are critical. Further research is warranted to understand which interventions can successfully improve HP performance of the 5As, and whether other models, such as the AAR,95 the ABC96 or Ask, Brief Advice, Cessation, Discuss97 approach may better facilitate HP implementation of SCC, and correspondingly improve quit rates in pregnant women. Standardised methods to assess the provision of SCC and the 5As in research or programme evaluations would aid future comparisons.

Conclusions

In a systematic review of HPs’ provision of SCC for pregnant women in 10 countries, meta-analyses were performed after combining like measures across studies where feasible. Pooled percentages revealed that HPs reliably ‘Ask’, ‘Advise’ and ‘Assess’ pregnant women about tobacco smoking. ‘Assist’, including assist by ‘prescribing NRT’, and ‘Arrange referral’ were much lower, and may be improved by appropriate interventions such as training, incentives or prompts. Meta-regressions were significant only for ‘Arrange referral’ for year and country. Further research may be required to understand other factors driving the heterogeneity between different studies. Standardised methods to assess the provision of SCC and the 5As are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GSG was responsible for the design of the review, publishing the protocol in PROSPERO, oversaw all aspects of the study and wrote the manuscript. LT conducted the searches with YBZ. LS did the data extraction, and with YBZ the quality analysis. KP conducted the meta-analyses and meta-regressions. GRG assisted GSG in writing the methods and results sections, and preparing tables. BB advised on study design and critically reviewed the manuscript. YBZ advised on manuscript drafts as senior author. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by a grant from Hunter Cancer Research Alliance, Australia.

Disclaimer: The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Competing interests: GSG reports grants from National Health and Medical Research Council, grants from Cancer Institute New South Wales, grants from Hunter Cancer Research Alliance, during the conduct of the study; grants from National Health and Medical Research Council, grants from Hunter New England Central Coast Primary Health Network, grants from Cancer Australia and Cure Cancer Australia, grants from Ministry of Health NSW, grants from John Hunter Hospital Charitable Trust, outside the submitted work. YBZ reports grants and others from Hunter Cancer Research Alliance, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Novartis NCH, personal fees from Pfizer Israel LTD, outside the submitted work.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary information.

References

- 1. Hofhuis W, de Jongste JC, Merkus PJFM. Adverse health effects of prenatal and postnatal tobacco smoke exposure on children. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:1086–90. 10.1136/adc.88.12.1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services The health consequences of Smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon General, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cornelius MD, Leech SL, Goldschmidt L, et al. Prenatal tobacco exposure: is it a risk factor for early tobacco experimentation? Nicotine Tob Res 2000;2:45–52. 10.1080/14622200050011295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lange S, Probst C, Rehm J, et al. National, regional, and global prevalence of smoking during pregnancy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e769–76. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30223-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res 2003;18:156–70. 10.1093/her/18.2.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schneider S, Huy C, Schütz J, et al. Smoking cessation during pregnancy: a systematic literature review. Drug Alcohol Rev 2010;29:81–90. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00098.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gould GS, Patten C, Glover M, et al. Smoking in pregnancy among Indigenous women in high-income countries: a narrative review. Nicotine Tob Res 2017;19:506–17. 10.1093/ntr/ntw288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bottorff JL, Poole N, Kelly MT, et al. Tobacco and alcohol use in the context of adolescent pregnancy and postpartum: a scoping review of the literature. Health Soc Care Community 2014;22:561–74. 10.1111/hsc.12091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rhodes-Keefe JM. Depression and smoking in the pregnant rural population: a literature review. OJRNHC 2015;15:60–73. 10.14574/ojrnhc.v15i1.340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Flemming K, Graham H, Heirs M, et al. Smoking in pregnancy: a systematic review of qualitative research of women who commence pregnancy as smokers. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:1023–36. 10.1111/jan.12066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Flemming K, McCaughan D, Angus K, et al. Qualitative systematic review: barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation experienced by women in pregnancy and following childbirth. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:1210-26 10.1111/jan.12580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crane CA, Hawes SW, Weinberger AH. Intimate partner violence victimization and cigarette smoking: a meta-analytic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2013;14:305–15. 10.1177/1524838013495962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gould GS, Bovill M, Clarke MJ, et al. Chronological narratives from smoking initiation through to pregnancy of Indigenous Australian women: a qualitative study. Midwifery 2017;52:27–33. 10.1016/j.midw.2017.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Graham H, Flemming K, Fox D, et al. Cutting down: insights from qualitative studies of smoking in pregnancy. Health Soc Care Community 2014;22:259–67. 10.1111/hsc.12080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ingall G, Cropley M. Exploring the barriers of quitting smoking during pregnancy: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Women Birth 2010;23:45–52. 10.1016/j.wombi.2009.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bovill M, Gruppetta M, Cadet-James Y, et al. Wula (voices) of Aboriginal women on barriers to accepting smoking cessation support during pregnancy: findings from a qualitative study. Women Birth 2018;31 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bar-Zeev Y, Lim LL, Bonevski B, et al. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation during pregnancy. Med J Aust 2018;208:46–51. 10.5694/mja17.00446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stead LF, Lancaster T. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012;(10). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gould GS, Lim LL, Mattes J. Prevention and treatment of smoking and tobacco use during pregnancy in selected Indigenous communities in high-income countries of the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand: an evidence-based review. Chest 2017;152:853–66. 10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American College of obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee opinion no. 471: smoking cessation during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brose LS, McEwen A, West R. Association between nicotine replacement therapy use in pregnancy and smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;132:660–4. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. NICE Quitting smoking in pregnancy and following childbirth - NICE public health guidance 26. Manchester National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zwar N, Richmond R, Borland R. Supporting smoking cessation: a guide for health professionals. Melbourne: The Royal Australian College of general practitioners, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ministry of Health Background and recommendations of the New Zealand guidelines for helping people to stop smoking, 2014. Available: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/backgroundrecommendations-new-zealand-guidelines-for-helpingstop-smoking-mar15-v2.pdf

- 25. Canadian Action Network for the Advancement Dissemination and adoption of practice-informed tobacco treatment. Canadian smoking cessation clinical practice guideline, 2011. Available: https://www.peelregion.ca/health/professionals/events/pdf/2013/canadaptt-summary-statements.pdf [Accessed May 2017].

- 26. Fiore MC BW, Cohen SJ, Dorfman SF, et al. Smoking cessation clinical practice guidelines No. 18. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Human and Health Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Okoli CTC, Greaves L, Bottorff JL, et al. Health care providers' engagement in smoking cessation with pregnant smokers. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2010;39:64–77. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01084.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baxter S, Everson-Hock E, Messina J, et al. Factors relating to the uptake of interventions for smoking cessation among pregnant women: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:685–94. 10.1093/ntr/ntq072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Siddiqi K, Mdege N. A global perspective on smoking during pregnancy. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e708–9. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30246-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Michie S, Wood C, Johnston M, et al. Chapter 1, general introduction. behaviour change techniques: the development and evaluation of a taxonomic method for reporting and describing behaviour change interventions (a suite of five studies involving consensus methods, randomised controlled trials and analysis of qualitative data). Southampton, UK: NIHR Journals Library, 2015: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lorencatto F, West R, Michie S. Specifying evidence-based behavior change techniques to aid smoking cessation in pregnancy. Nicotine Tob Res 2012;14:1019–26. 10.1093/ntr/ntr324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Campbell KA, Cooper S, Fahy SJ, et al. 'Opt-out' referrals after identifying pregnant smokers using exhaled air carbon monoxide: impact on engagement with smoking cessation support. Tob Control 2017;26:300–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-Analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (moose) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, et al. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 2002;12:1284–99. 10.1177/1049732302238251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, et al. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2010;1:97–111. 10.1002/jrsm.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. CRC press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bar-Zeev Y, Bonevski B, Twyman L, et al. Opportunities missed: a cross-sectional survey of the provision of smoking cessation care to pregnant women by Australian general practitioners and obstetricians. Nic Tob Res 2017;19:636–41. 10.1093/ntr/ntw331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Abatemarco DJ, Steinberg MB, Delnevo CD, et al. Midwives' knowledge, perceptions, beliefs, and practice supports regarding tobacco dependence treatment. J Midwifery Womens Health 2007;52:451–7. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Amarin ZO. Obstetricians, gynecologists and the anti-smoking campaign: a national survey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2005;119:156–60. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bakker MJ, de Vries H, Mullen PD, et al. Predictors of perceiving smoking cessation counselling as a midwife's role: a survey of Dutch midwives. Eur J Public Health 2005;15:39–42. 10.1093/eurpub/cki109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Beenstock J, Sniehotta FF, White M, et al. What helps and hinders midwives in engaging with pregnant women about stopping smoking? A cross-sectional survey of perceived implementation difficulties among midwives in the North East of England. Implement Sci 2012;7 10.1186/1748-5908-7-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Berrueta M, Morello P, Alemán A, et al. Smoking patterns and receipt of cessation services among pregnant women in Argentina and Uruguay. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:1116–25. 10.1093/ntr/ntv145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bonollo DP, Zapka JG, Stoddard AM, et al. Treating nicotine dependence during pregnancy and postpartum: understanding clinician knowledge and performance. Patient Educ Couns 2002;48:265–74. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00023-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bull L, Whitehead E. Smoking cessation intervention with pregnant women and new parents: a survey of health visitors, midwives and practice nurses. J Neonatal Nurs 2006;12:209–15. 10.1016/j.jnn.2006.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Castrucci BC, Culhane JF, Chung EK, et al. Smoking in pregnancy: patient and provider risk reduction behavior. J Public Health Manag Pract 2006;12:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chang JC, Dado D, Frankel RM, et al. When pregnant patients disclose substance use: missed opportunities for behavioral change counseling. Patient Educ Couns 2008;72:394–401. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chang JC, Alexander SC, Holland CL, et al. Smoking is bad for babies: obstetric care providers' use of best practice smoking cessation counseling techniques. Am J Health Promot 2013;27:170–6. 10.4278/ajhp.110624-QUAL-265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Clasper P, White M. Smoking cessation interventions in pregnancy: practice and views of midwives, GPs and obstetricians. Health Educ J 1995;54:150–62. 10.1177/001789699505400204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Coleman-Cowger VH, Anderson BL, Mahoney J, et al. Smoking cessation during pregnancy and postpartum: practice patterns among obstetrician-gynecologists. J Addict Med 2014;8:14–24. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Condliffe L, McEwen A, West R. The attitude of maternity staff to, and smoking cessation interventions with, childbearing women in London. Midwifery 2005;21:233–40. 10.1016/j.midw.2004.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cooke M, Mattick RP, Barclay L. Predictors of brief smoking intervention in a midwifery setting. Addiction 1996;91:1715–25. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1996.tb02274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Eiser JR, Main N, Lee A, et al. Midwife attitudes and advice to pregnant smokers. Addiction Research 1999;7:355–68. 10.3109/16066359909004392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. England LJ, Anderson BL, Tong VTK, et al. Screening practices and attitudes of obstetricians-gynecologists toward new and emerging tobacco products. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211:695.e1–7. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.05.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Floyd RL, Belodoff B, Sidhu J, et al. A survey of obstetrician-gynecologists on their patients' use of tobacco and other drugs during pregnancy. J Neonatal Perinatal Med 2001;6:201–7. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Glover M, Paynter J, Bullen C, et al. Supporting pregnant women to quit smoking: postal survey of new Zealand general practitioners and midwives' smoking cessation knowledge and practices. N Z Med J 2008;121:53–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Grangé G, Vayssière C, Borgne A, et al. Characteristics of tobacco withdrawal in pregnant women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2006;125:38–43. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Grimley DM, Bellis JM, Raczynski JM, et al. Smoking cessation counseling practices: a survey of Alabama obstetrician-gynecologists. South Med J 2001;94:297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hartmann KE, Wechter ME, Payne P, et al. Best practice smoking cessation intervention and resource needs of prenatal care providers. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:765–70. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000280572.18234.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Helwig AL, Swain GR, Gottlieb M. Smoking cessation intervention: the practices of maternity care providers. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 1998;11:336–40. 10.3122/15572625-11-5-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Herbert R, Coleman T, Britton J. U.K. general practitioners' beliefs, attitudes, and reported prescribing of nicotine replacement therapy in pregnancy. Nicotine Tob Res 2005;7:541–6. 10.1080/14622200500186015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hickner J, Cousineau A, Messimer S. Smoking cessation during pregnancy: strategies used by Michigan family physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract 1990;3:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hoekzema L, Werumeus Buning A, Bonevski B, et al. Smoking rates and smoking cessation preferences of pregnant women attending antenatal clinics of two large Australian maternity hospitals. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2014;54:53–8. 10.1111/ajo.12148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Howard L, Rowe M, Bewley S, et al. 828 – smoking cessation in pregnant women with mental disorders: a cohort and nested qualitative study. Eur Psychiatry 2013;28 10.1016/S0924-9338(13)76003-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Jones D. Changing practice. exploring the value of smoking cessation advice. Br J Midwifery 2003;11:212–5. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jordan TR, Dake JR, Price JH. Best practices for smoking cessation in pregnancy: do obstetrician/gynecologists use them in practice? J Womens Health 2006;15:400–41. 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lemola S, Meyer-Leu Y, Samochowiec J. Control beliefs are related to smoking prevention in prenatal care. Inside Childbirth Education 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mabbutt J, Bauman A, Moshin M. Tobacco use of pregnant women and their male partners who attend antenatal classes: what happened to routine quit smoking advice in pregnancy? Aust N Z J Public Health 2002;26:571–2. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2002.tb00368.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. McEwen A, West R, Mitchell S, et al. Problems identifying pregnant smokers. Br J Midwifery 2003;11. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mejia R, Martinez VG, Gregorich SE, et al. Physician counseling of pregnant women about active and secondhand smoking in Argentina. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2010;89:490–5. 10.3109/00016341003739567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Moran S, Thorndike AN, Armstrong K, et al. Physicians' missed opportunities to address tobacco use during prenatal care. Nicotine Tob Res 2003;5:363–8. 10.1080/1462220031000094150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mullen PD, Pollak KI, Titus JP, et al. Prenatal smoking cessation counseling by Texas obstetricians. Birth 1998;25:25–31. 10.1046/j.1523-536x.1998.00025.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Murphy K, Steyn K, Mathews C. The midwife's role in providing smoking cessation interventions for pregnant women: the views of midwives working with high risk, disadvantaged women in public sector antenatal services in South Africa. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;53:228–37. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Oncken CA, Pbert L, Ockene JK, et al. Nicotine replacement prescription practices of obstetric and pediatric clinicians. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:261–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Owen L, McNeill A. The role of health professionals in reducing smoking in pregnancy. Contemporary Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1999;11:235–8. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Passey ME, D'Este CA, Sanson-Fisher RW. Knowledge, attitudes and other factors associated with assessment of tobacco smoking among pregnant Aboriginal women by health care providers: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2012;12:165 10.1186/1471-2458-12-165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Passey ME, Sanson-Fisher RW. Provision of antenatal smoking cessation support: a survey with pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:746–9. 10.1093/ntr/ntv019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Passey ME, Sanson-Fisher RW, Stirling JM. Supporting pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to quit smoking: views of antenatal care providers and pregnant Indigenous women. Matern Child Health J 2014;18:2293–9. 10.1007/s10995-013-1373-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Price JH, Jordan TR, Dake JA. Obstetricians and gynecologists' perceptions and use of nicotine replacement therapy. J Community Health 2006;31:160–75. 10.1007/s10900-005-9009-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Price JH, Jordan TR, Dake JA. Perceptions and use of smoking cessation in nurse-midwives' practice. J Midwifery Womens Health 2006;51:208–15. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Pullon S, Webster M, McLeod D, et al. Smoking cessation and nicotine replacement therapy in current primary maternity care. Aust Fam Physician 2004;33:94–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Röske K, Hannöver W, Thyrian JR, John U, et al. Smoking cessation counselling for pregnant and postpartum women among midwives, gynaecologists and paediatricians in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2009;6:96–107. 10.3390/ijerph6010096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Solberg LI, Parker ED, Foldes SS, et al. Disparities in tobacco cessation medication orders and fills among special populations. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:144–51. 10.1093/ntr/ntp187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Tappin DM, MacAskill S, Bauld L, et al. Smoking prevalence and smoking cessation services for pregnant women in Scotland. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2010;5:1 10.1186/1747-597X-5-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Thyrian JR, Hannöver W, Röske K, et al. Midwives' attitudes to counselling women about their smoking behaviour during pregnancy and postpartum. Midwifery 2006;22:32–9. 10.1016/j.midw.2005.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tong VT, England LJ, Dietz PM, et al. Smoking patterns and use of cessation interventions during pregnancy. Am J Prev Med 2008;35:327–33. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tran S-TT, Rosenberg KD, Carlson NE. Racial/Ethnic disparities in the receipt of smoking cessation interventions during prenatal care. Matern Child Health J 2010;14:901–9. 10.1007/s10995-009-0522-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Tzelepis F, Daly J, Dowe S, et al. Supporting aboriginal women to quit smoking: antenatal and postnatal care providers' confidence, attitudes, and practices. Nicotine Tob Res 2017;19:642–6. 10.1093/ntr/ntw286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Walsh RA, Redman S, Brinsmead MW, et al. Smoking cessation in pregnancy: a survey of the medical and nursing directors of public antenatal clinics in Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1995;35:144–50. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.1995.tb01857.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Zapka JG, Pbert L, Stoddard AM, et al. Smoking cessation counseling with pregnant and postpartum women: a survey of community health center providers. Am J Public Health 2000;90:78–84. 10.2105/ajph.90.1.78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Cooke M, Mattick RP, Campbell E. The influence of individual and organizational factors on the reported smoking intervention practices of staff in 20 antenatal clinics. Drug Alcohol Rev 1998;17:175–85. 10.1080/09595239800186981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bar‐Zeev Y, Bonevski B, Gruppetta M, et al. Clinician factors associated with prescribing nicotine replacement therapy in pregnancy: a cross‐sectional survey of Australian obstetricians and general practitioners. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Vidrine JI, Shete S, Cao Y, et al. Ask-Advise-Connect: a new approach to smoking treatment delivery in health care settings. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:458–64. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Crane R. The most addictive drug, the most deadly substance: smoking cessation tactics for the busy clinician. Prim Care 2007;34:117–35. 10.1016/j.pop.2007.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Chamberlain C, O'Mara-Eves A, Porter J, et al. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;2 10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Cochrane Collaboration Effective practice and organisation of care (EPOC), 2015. Available: https://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy2018

- 96. Ministry of Health Implementing the ABC approach for smoking cessation: framework and work programme. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Gould GS, Bittoun R, Clarke MJ. A pragmatic guide for smoking cessation counselling and the initiation of nicotine replacement therapy for pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smokers. J Smok Cessat 2015;10:96–105. 10.1017/jsc.2014.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026037supp001.pdf (495KB, pdf)