Abstract

Introduction

Drug–drug interaction (DDI) alerts in hospital electronic medication management (EMM) systems are generated at the point of prescribing to warn doctors about potential interactions in their patients’ medication orders. This project aims to determine the impact of DDI alerts on DDI rates and on patient harm in the inpatient setting. It also aims to identify barriers and facilitators to optimal use of alerts, quantify the alert burden posed to prescribers with implementation of DDI alerts and to develop algorithms to improve the specificity of DDI alerting systems.

Methods and analysis

A controlled pre-post design will be used. Study sites include six major referral hospitals in two Australian states, New South Wales and Queensland. Three hospitals will act as control sites and will implement an EMM system without DDI alerts, and three as intervention sites with DDI alerts. The medical records of 280 patients admitted in the 6 months prior to and 6 months following implementation of the EMM system at each site (total 3360 patients) will be retrospectively reviewed by study pharmacists to identify potential DDIs, clinically relevant DDIs and associated patient harm. To identify barriers and facilitators to optimal use of alerts, 10–15 doctors working at each intervention hospital will take part in observations and interviews. Non-identifiable DDI alert data will be extracted from EMM systems 6–12 months after system implementation in order to quantify alert burden on prescribers. Finally, data collected from chart review and EMM systems will be linked with clinically relevant DDIs to inform the development of algorithms to trigger only clinically relevant DDI alerts in EMM systems.

Ethics and dissemination

This research was approved by the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (18/02/21/4.07). Study results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at local and international conferences and workshops.

Keywords: drug-drug interaction, decision support, alert, alert fatigue

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A controlled pre-post study will evaluate the impact of drug–drug interaction (DDI) alerts on errors and harm. This is the most rigorous design possible for hospital-wide implementations of electronic medication management systems when randomisation of hospitals is not feasible.

This study uses a large-scale, multisite, mixed-methods approach.

This study is one of a small number to assess actual harm to patients from DDIs.

Results may not be generalisable to hospitals with substantially different work practices or DDI alerting systems.

This study is limited in that assessments of patient harm will be done retrospectively from information contained in medical records.

Introduction

Drug–drug interactions (DDI) occur when two or more medications are taken in combination that lead to a change in the effects of one or more medications.1 2 The result can be therapeutic failure, where the medications do not achieve their anticipated effects, or adverse patient outcomes, such as bleeding or kidney damage.3 The prevalence of DDIs is on the rise as our population ages, as patients have a greater number of chronic conditions, and use more medicines concurrently. A cross-sectional analysis of dispensing data for over 300 000 residents in Scotland between 1995 and 2010 revealed that the rate of potentially serious DDIs more than doubled in the 15-year time frame.4 Not unexpectedly, a strong relationship exists between the number of medications prescribed and the probability of a DDI occurring.5 This is a highly significant problem for patients in hospital, who take on average 12 medications.6 7

Studies of DDI rates in hospitals report highly variable results, with the rate of DDIs dependent on how they are defined (eg, ‘potential DDI’ vs ‘actual DDI’), measured (eg, per patient, per order) and identified (eg, via chart review vs automatic detection using software). The quality of some previous studies is also questionable, with many neglecting to specify these key pieces of information. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis which aimed to determine the prevalence of DDIs in hospitalised patients, it was found that 33% of patients experienced a potential DDI during their hospital stay.8 Studies rarely went further than identifying potential DDIs to determine which of these represented clinically relevant DDIs for a patient or resulted in actual patient harm. In the small number of studies that did this, potential DDIs proved to be very poor predictors of DDI-related harm, with only approximately 2% of potential DDIs associated with actual patient harm.8

Despite this, a common approach taken by organisations is to implement decision support for prescribers in electronic medication management (EMM) systems to reduce DDIs. Although DDIs are predictable in nature, the sheer volume of known drug interactions is likely to contribute to poor DDI detection, with research showing that prescribers are often unable to recognise DDIs.9 Decision support typically comprises computerised alerts, which are generated at the point of prescribing to warn doctors about potential interactions in their patients’ medication orders. There is good evidence to show that when well designed and targeted, computerised alerts can have positive effects on prescribing behaviour.10 11 However, accompanying this evidence are a large number of studies demonstrating alerts are overridden by users, along with accounts of user annoyance and frustration. Clinicians override 49%–96% of drug alerts12 and our own research has shown that in certain contexts, doctors do not read the majority of alerts presented.13Alert fatigue, when users become overwhelmed and desensitised to alert presentation, is the primary reason for alerts being ignored.

Although DDI alerts have the potential to reduce serious medication errors, there has been limited research evaluating their effectiveness in both reducing DDIs and patient harm. Two studies have examined the impact of a single customised DDI alert on the concurrent ordering of two medications, but reported inconsistent findings.14 15 In one case, introduction of a DDI alert also resulted in unintended consequences (eg, delays in appropriate treatment).15 To date, no research has examined the impact of DDI alert sets (ie, a suite of DDI alerts, not a single DDI alert) on DDIs or harm.

Previous evaluations of DDI alerts have focused on a review of the number of alerts generated and overridden (ie, dismissed with no change made to a medication order) by prescribers.16 This research has shown that prescribers receive very large numbers of DDI alerts and override almost all alerts (over 90%) that are presented. Despite international efforts to improve DDI alerts, override rates remain as high as they were over a decade ago.17 There is now little doubt that improving alert specificity is critical for reducing frequent interruptions to prescriber workflow (ie, too many alerts) and improving the effectiveness of computerised alerts to prevent errors.18 19

Despite the scarcity of evidence demonstrating that DDI alerts reduce DDIs and patient harm, the US Government’s Meaningful Use Program,20 and Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society Electronic Medical Record Adoption Model21 both recommend implementation of drug interaction checking within electronic medical records. However, a major consequence of DDI alert inclusion in EMM systems is the alert burden this places on prescribers. Thus, the inclusion of DDI alerts in EMM systems is likely to result in prescribers presented with hundreds of DDI alerts a day. Alert fatigue is almost certain to eventuate, with doctors learning to ignore all alerts, even those that present safety critical information. Thus, decisions about which types of alerts to include in EMM systems are non-trivial in terms of both ensuring a positive impact on patient care and a minimal impact on prescribers’ cognitive load.

With limited evidence available to guide the implementation of DDI alerts, hospitals are faced with a difficult decision when implementing EMM systems: should DDI alerts be turned on, and if so, which alerts? Such decisions should be informed by evidence which demonstrates that alerts align well with prescriber workflow, are effective in reducing errors and result in reduced patient harm. No such evidence currently exists. In recognising this significant evidence gap, we are partnering with eHealth NSW and eHealth QLD to undertake a comprehensive evaluation of DDI alerts. The project aims to:

Determine the impact of DDI alerts on DDI rates and patient harm.

Identify barriers and facilitators to optimal use of alerts.

Quantify the alert burden posed to prescribers with implementation of DDI alerts in hospital medication systems.

Develop algorithms to predict clinically relevant DDIs.

Methods and analysis

Study design

Table 1 provides a summary of the study design and methods to be used, and the main outcome measures (defined in table 2). A controlled pre-post design will be adopted. This is the most rigorous design possible for hospital-wide implementations of EMM systems when randomisation of hospitals is not feasible.

Table 1.

Study design and outcomes

| Aim | Design/method | Outcome measures/outputs | When collected |

| 1 | Controlled pre-post study involving retrospective review of medical records | Rates of potential DDIs Rates of clinically relevant DDIs Rates of patient harm |

Before and after EMM |

| 2 | Human factors evaluation—observations and interviews with prescribers | Alert usability and acceptability, barriers and facilitators to optimal use of alerts | After EMM |

| 3 | Analysis of alert data extracted from EMM systems | Alert burden (alerts/patient; alerts/order; alerts/prescriber) | After EMM |

| 4 | Analysis of patient and medication information collected during retrospective review and extracted from clinical information systems | Algorithms which predict clinically relevant DDIs | After EMM |

DDI, drug–drug interaction; EMM, electronic medication management.

Table 2.

Definitions of potential DDIs, clinically relevant DDIs and harm resulting from DDIs

| Category | Definition |

| Potential drug–drug interaction | A potential DDI is defined as two or more drugs interacting with each other in such a way that the effectiveness or toxicity of one or more drugs is potentially altered. |

| Clinically relevant drug–drug interaction | A clinically relevant DDI is defined as two or more drugs interacting with each other in such a way that the effectiveness or toxicity of one or more drugs is highly likely to be altered when taking into account individual patient factors (age, gender, diagnosis, comorbidities) and medication order factors (dose and route of potentially interacting medications). |

| Drug–drug interaction that resulted in patient harm | Drug pairs that interacted and resulted in harm to the patient. Identification of harm is based on clinical evidence and confirmed by symptoms and investigations recorded in the patient record. Harm constitutes ‘impairment of structure or function of the body and/or any deleterious effect arising there from, including disease, injury, suffering, disability and death, and may be physical, social or psychological.’34 |

DDI, drug–drug interaction.

Research project setting

The project commenced in December 2017 and is due to be completed in December 2021. The study will be conducted at six major referral hospitals in two Australian states, New South Wales (NSW) and Queensland (QLD). Three hospitals will act as control sites and will implement an EMM system without DDI alerts, and three as intervention sites with DDI alerts. Hospitals were allocated to intervention or control based on their decision to include or exclude DDI alerts in their implementation plan. All study sites used paper medication charts prior to implementation of EMM systems and all sites have replaced or will replace paper charts with an EMM system.

This study will evaluate only one component of the EMM system: clinical decision support in the form of DDI alerts. DDI alerts to be implemented at each site are interruptive, require an override reason to be entered, but none are hard-stop alerts preventing the prescriber from continuing with their order. All intervention hospital EMM systems will use the Cerner Multum DDI knowledge base (https://www.cerner.com/solutions/drug-database) for DDI detection, although some local customisation is expected. A list of all DDI alerts which have been incorporated into EMM systems will be provided to researchers following implementation.

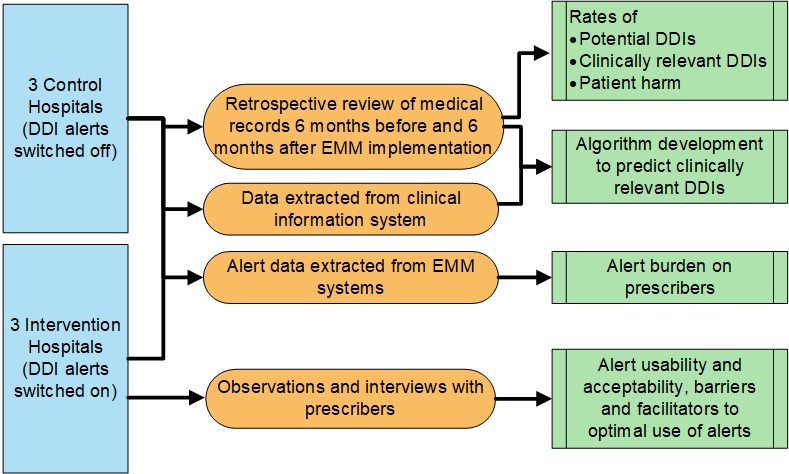

This study includes three main methods of data collection, namely retrospective chart review (aims 1 and 4), observations and interviews (aim 2) and data extraction from clinical information systems (aims 3 and 4). See figure 1. Our methodological approach is presented separately for each part of the study.

Figure 1.

Overall study design. DDI, drug–drug interaction; EMM, electronic medication management.

Part 1: retrospective chart review

The medical records of 280 patients admitted in the 6 months prior to and 6 months following implementation of the EMM system at each site will be retrospectively reviewed (total 3360 patients). Patients will be randomly selected from all patients admitted to study hospitals during a 1-week period 6 months before and 6 months after EMM. Patients who visited the emergency department but were not admitted to wards and those in wards where a different EMM system was in use (ie, the intensive care unit and oncology department) will be excluded. Medication orders for patients will initially be entered into Stockley’s Interactions Checker (an authoritative international source of drug interaction information; http://www.medicinescomplete.com/—see online supplementary appendix 1) to identify potential DDIs. Based on the severity classifications used by the Stockley’s checker, potential DDIs of the two highest severity levels (ie, severe and moderate) will undergo further review. Study pharmacists (not affiliated with any study hospital) will complete a detailed audit of patients’ medical records to determine whether these potential DDIs represent clinically relevant DDIs, taking into account patient factors such as age, sex, renal function and medication order factors, such as route.

bmjopen-2018-026034supp001.pdf (178.3KB, pdf)

Any evidence of possible harm resulting from the DDIs (eg, abnormal test result, administration of an antidote) will also be extracted from patient records. When possible harm is identified, these patient cases will be presented to an expert panel of clinical pharmacologist physicians who will determine whether these possible harms constitute actual patient harm resulting from the DDI. Severity of harm to patients will be classified on the 5-point Severity Assessment Code Scale,22 used in our past research.23 24 Clinician confidence in the association between the DDI and identified harm will be classified using the WHO-Uppsala Monitoring Centre Algorithm.25

The pharmacists will also note any documentation which suggests that a DDI was recognised yet intentionally prescribed (eg, the DDI was considered by the prescriber, who reduced a medication dose, increased monitoring or took no additional actions). During post-EMM implementation data collection, reviewers will record whether a DDI alert was triggered for the potential DDIs.

The limitations of medical records data are inherent to this methodology, and will be minimised by using multiple sources of information from the records, and by using both pharmacists and clinical pharmacologist physicians to assess clinical outcomes and their link to DDIs. The drug interaction checker used to identify potential DDIs (Stockley’s) differs from the DDI knowledge base operating in the ‘intervention’ EMM systems. There is large variability in the DDIs included in different knowledge bases and reference sources.26 We selected Stockley’s for DDI identification as it is considered to be the gold standard and often used as a comparison point for other reference sources.27 28

Sample size calculation

We identified only two high-quality papers that report the proportion of patient admissions with a potential DDI, however only one of these studies used comparable methodology to our planned study.29 That study found that 56% of patients experienced at least one potential DDI during their hospital stay. No research to date has examined the impact of DDI alerts on DDI rates. Our two expert clinical pharmacologist physicians (ROD and SH) estimate a 25% change in potential DDIs to be clinically significant. We used this estimate of a clinically significant change and the 56% baseline figure to estimate the sample size required in our study with a two-sided test for proportions (90% power and a 95% CI). The number of patient admissions to be reviewed per study period at each site was determined to be 280. Thus, across the entire study period and the six study sites, 3360 patient admissions will be audited.

Data analysis

To determine the impact of DDI alerts on DDIs, we will conduct an intention to treat analysis. A generalised linear modelling approach will be applied to examine if implementation of DDI alerts was associated with a significant reduction in potential DDI rates, clinically relevant DDI rates and the occurrence and severity of patient harm. Data collected at the six hospitals will be used. Rates of DDIs and harm from the intervention and control hospitals will be compared at baseline and after EMM implementation.

Part 2: observations and interviews

Participants

Approximately 10–15 doctors working at each intervention hospital will take part in observations and interviews. Doctors will be directly approached while working on wards and invited to take part in the study. All doctors who prescribe medications are eligible to participate. Participation is voluntary and all doctors will be required to provide written informed consent. A snowball sampling approach will also be used where doctors who participate in the study will be asked to inform other doctors about the study. This recruitment approach has proven highly successful in our previous evaluations of decision support.13 30 31

Procedure

Prescribers will be shadowed by a human factors researcher during medication-related tasks (eg, ward rounds, medicine review) and all interactions with alerts will be recorded. In particular, the researcher will note if alerts are read, and if alerts impacted on medication-related work (eg, medication order changed, alert content discussed with a colleague). Approximately 30 hours of observation at each site is planned. Prescribers will also be invited to participate in a brief semistructured interview. Interview questions will focus on usability and acceptability of the DDI alerts in their hospital EMM system (eg, usefulness, integration into workflow), see box 1.

Box 1. Semistructured interview questions for prescribers.

Basic demographics

Role.

Years practising medicine.

Ward/specialty.

EMM system in use.

Length of time using EMM system.

Opinion of EMMS and DDI alerts

Do you prefer using paper or electronic charts? Why?

What alerts are operational in your EMM system?

Roughly how many DDI alerts do you see in a day?

Do you find the DDI alerts useful or bothersome?

Do you read the alerts? Which ones and why?

Do you think alerts are effective in changing prescribing decisions? How often do they result in a change to your prescribing? Can you think of an occasion when an alert impacted on your prescribing?

If there was an option to remove DDI alerts from the EMMS, would you support their removal? Why?

Can you think of any changes needed to the DDI alerts?

Any other comments?

DDI, drug–drug interaction; EMM, electronic medication management.

Data analysis

Detailed field notes on the impact of computerised alerts on medication-related work will be taken during observations. Interviews with prescribers will be audiotaped and transcribed. Content will be deidentified and analysed by two investigators to identify barriers and facilitators to optimal use of alerts. A general inductive approach to analysis will be used.32 Investigators will meet periodically throughout qualitative data collection to discuss barriers and facilitators and determine at what point saturation of themes is achieved (ie, no new barriers and facilitators are apparent). Recruitment of participants will continue at each site until theme saturation is reached. This is viewed as an appropriate strategy for determining sample size in qualitative research.33 Emergent themes from each site will be compared and contrasted to determine differences in barriers and facilitators, and on perceived usefulness, usability and acceptability of DDI alerts in EMM.

Part 3: analysis of data extracted from clinical information systems

Part 3A: analysis of data to determine alert burden

Non-identifiable DDI alert data (including number of alerts triggered) will be extracted from intervention hospital EMM systems 6–12 months after system implementation. Data will be used to quantify alert burden on prescribers. That is, the number of DDI alerts encountered and overridden. Descriptive statistics will be used to determine the number of medications prescribed per patient admission, the number of DDI alerts encountered as a proportion of the number of medications prescribed and the proportion of DDI alerts overridden.

Part 3B: analysis of data to develop algorithms

Data extracted from hospital clinical information systems will be linked with data collected during retrospective chart review, including information related to clinically relevant DDIs. Decision tree modelling and Bayesian modelling will be used to develop algorithms which predict the occurrence of clinically relevant DDIs to improve the specificity and positive predictive value of identifying these DDIs. If relevant, a mixed effect model will be applied to consider the correlation between medications ordered by the same prescribers.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or the public were involved in any stage of the research process for this study.

Ethics and dissemination

This research was approved by the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (18/02/21/4.07) and ratified by Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee.

The research will fill a significant knowledge gap by providing data on how frequently DDIs occur in hospitalised patients, what proportion of potential DDIs are clinically relevant and what proportion lead to patient harm. Importantly, this research will generate the first data on the effectiveness of DDI alerts to reduce medication errors and prevent patient harm. It will also provide information on the alert burden posed to prescribers with implementation of DDI alerts and on how DDI alerts impact on clinicians’ work.

Doctors are increasingly being asked to incorporate new technology into their work with little assessment of the ways in which systems may adversely impact their workflow or efficiency. Our human factors evaluation provides an in-depth examination of this impact, identifies barriers to optimal use of alerts and uses this evidence to inform future alert design and future EMM education for clinicians. Adopting a human factors approach to evaluation and incorporating user input into redesign will increase likelihood of optimal use of alerts, and ensure systems are targeting problem areas and are easy to use and integrate into current practice. Thus, our human factors evaluation will facilitate the direct translation of research into optimal system redesign and use.

Another outcome of the research will be algorithms to predict the occurrence of clinically relevant DDIs. When incorporated into EMM systems, these algorithms would have the potential to improve specificity of DDI alerting systems—alerts will only trigger to warn of clinically relevant DDIs, not potential DDIs. This will reduce the alert burden to prescribers substantially.

Our results will have both immediate and long-term effects on Australian hospitals, and more broadly, as hospitals worldwide implement EMM systems. Study results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at local and international conferences. Key study findings will be communicated to NSW and QLD hospitals, and system vendors via annual workshops. With assistance from our partners, eHealth NSW and eHealth QLD, results from this study will also be integrated into state-wide design of EMM systems.

This research will provide much needed evidence to inform decisions about selection and design of computerised alerts in EMM systems in Australian hospitals and internationally. EMM systems are becoming a central tool in clinical practice and over the next decade the majority of clinical work will be performed using and guided by this technology. Working closely with our partner investigators, our study will produce evidence to ensure that decision support is effective in producing clinical benefits that outweigh any potentially dangerous disruptions to clinical work due to excessive alerting.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript. MTB conceived the study and led the revisions of the draft manuscript. WYZ and BAVD assisted in drafting the manuscript and in project management, including ethics approval. MTB, LL, JW, ROD and SH are chief investigators on the project and all made contributions to the project in their specific areas of expertise. AH, PK, CM, MD, LN, RS and PD are associate investigators and provided input to the protocol, particularly with respect to electronic systems, planned translation and practical aspects of the study.

Funding: This work is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Partnership Grant APP1134824) in partnership with eHealth NSW and eHealth QLD.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This research was approved by the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (18/02/21/4.07) and ratified by Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Wolverton SE, et al. Chapter 236. Drug interactions In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al., eds Ftizpatrick's dermatology in general medicine, 2012: 8. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roden DM, et al. Chapter 5: Principles of clinical pharmacology In: Long DL, Facui AS, Kasper DL, et al., eds Harrison's principles of internal medicine, 2012: 18. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zwart-van Rijkom JEF, Uijtendaal EV, ten Berg MJ, et al. Frequency and nature of drug-drug interactions in a Dutch university hospital. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;68:187–93. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03443.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guthrie B, Makubate B, Hernandez-Santiago V, et al. The rising tide of polypharmacy and drug-drug interactions: population database analysis 1995–2010. BMC Med 2015;13:1–10. 10.1186/s12916-015-0322-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnell K, Klarin I. The relationship between number of drugs and potential drug-drug interactions in the elderly: a study of over 600,000 elderly patients from the Swedish prescribed drug register. Drug Saf 2007;30 10.2165/00002018-200730100-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coombes ID, Pillans PI, Storie WJ, et al. Quality of medication ordering at a large teaching hospital. Australian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 2001;31:102–6. 10.1002/jppr2001312102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baysari MT, Reckmann MH, Li L, et al. Failure to utilize functions of an electronic prescribing system and the subsequent generation of 'technically preventable' computerized alerts. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:1003–10. 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zheng WY, Richardson LC, Li L, et al. Drug-Drug interactions and their harmful effects in hospitalised patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2018;74:15–27. 10.1007/s00228-017-2357-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ko Y, Malone DC, Skrepnek GH, et al. Prescribers' knowledge of and sources of information for potential drug-drug interactions: a postal survey of US prescribers. Drug Saf 2008;31:525–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schedlbauer A, Prasad V, Mulvaney C, et al. What evidence supports the use of computerized alerts and prompts to improve clinicians' prescribing behavior? J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:531–8. 10.1197/jamia.M2910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bright TJ, Wong A, Dhurjati R, et al. Effect of clinical decision-support systems: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:29–43. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201207030-00450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, et al. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:138–47. 10.1197/jamia.M1809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baysari MT, Westbrook JI, Richardson KL, et al. The influence of computerized decision support on prescribing during ward-rounds: are the decision-makers targeted? J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:754–9. 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Strom BL, Schinnar R, Bilker W, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a customized electronic alert requiring an affirmative response compared to a control group receiving a commercial passive CPOE alert: NSAID--warfarin co-prescribing as a test case. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2010;17:411–5. 10.1136/jamia.2009.000695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Strom BL, Schinnar R, Aberra F, et al. Unintended effects of a computerized physician order entry nearly hard-stop alert to prevent a drug interaction: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1578–83. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smithburger PL, Buckley MS, Bejian S, et al. A critical evaluation of clinical decision support for the detection of drug-drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2011;10:871–82. 10.1517/14740338.2011.583916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bryant AD, Fletcher GS, Payne TH. Drug interaction alert override rates in the meaningful use era: no evidence of progress. Appl Clin Inform 2014;5:802–13. 10.4338/ACI-2013-12-RA-0103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duke JD, Bolchini D. A successful model and visual design for creating context-aware drug-drug interaction alerts. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2011;2011:339–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seidling HM, Klein U, Schaier M, et al. What, if all alerts were specific - estimating the potential impact on drug interaction alert burden. Int J Med Inform 2014;83:285–91. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Centre for Disease Control and Prevention Meaningful use. Secondary meaningful use, 2017. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/ehrmeaningfuluse/introduction.html

- 21. Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society Electronic medical record adoption model. secondary electronic medical record adoption model, 2018. Available: https://www.himssanalytics.org/emram

- 22. New South Wales Health Department Severity assessment code (SAC) matrix. Sydney: NSW Health, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Westbrook JI, Reckmann M, Li L, et al. Effects of two commercial electronic prescribing systems on prescribing error rates in hospital in-patients: a before and after study. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001164 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Westbrook JI, Woods A, Rob MI, et al. Association of interruptions with an increased risk and severity of medication administration errors. Arch Intern Med. In Press 2010;170:683–90. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Health Organization - Uppsala Monitoring Centre The use of the WHO-UMC system for standardized case causality assessment. Secondary the use of the WHO-UMC system for standardized case causality assessment. Available: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/safety_efficacy/WHOcausality_assessment.pdf

- 26. Fung KW, Kapusnik-Uner J, Cunningham J, et al. Comparison of three commercial knowledge bases for detection of drug-drug interactions in clinical decision support. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2017;24:806–12. 10.1093/jamia/ocx010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reis AMM, Cassiani SHDB. Evaluation of three brands of drug interaction software for use in intensive care units. Pharm World Sci 2010;32:822–8. 10.1007/s11096-010-9445-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vonbach P, Dubied A, Krähenbühl S, et al. Evaluation of frequently used drug interaction screening programs. Pharm World Sci 2008;30:367–74. 10.1007/s11096-008-9191-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vonbach P, Dubied A, Krähenbühl S, et al. Prevalence of drug–drug interactions at hospital entry and during hospital stay of patients in internal medicine. Eur J Intern Med 2008;19:413–20. 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baysari MT, Del Gigante J, Moran M, et al. Redesign of computerized decision support to improve antimicrobial prescribing. A controlled before-and-after study. Appl Clin Inform 2017;8:949–63. 10.4338/ACI2017040069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baysari MT, Westbrook JI, Richardson K, et al. Optimising computerised alerts within electronic medication management systems: a synthesis of four years of research. Stud Health Technol Inform 2014;204:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval 2006;27:237–46. 10.1177/1098214005283748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 3rd edn NewBury Park, CA: Sage Publications Inc, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34. WHO Chapter 3 The international classification for patient safety key concepts and preferred terms In: Final technical report for the conceptual framework for the International classification for patient safety, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026034supp001.pdf (178.3KB, pdf)