Abstract

Objective

China’s national hepatitis burden is high. This study aims to provide a detailed national-level description of the reported incidence of viral hepatitis in China during 2004–2016.

Design

Observational study.

Setting

Data were obtained from China’s National Notifiable Disease Reporting System, and changing trends were estimated by joinpoint regression analysis.

Participants

In this system, 16 927 233 reported viral hepatitis cases occurring during 2004–2016 were identified.

Primary outcome measure

Incidence rates per 100 000 person-years and changing trends were calculated.

Results

There were 16 927 233 new cases of viral hepatitis reported in China from 2004 to 2016. Hepatitis B (HBV) (n=13 543 137, 80.00%) and hepatitis C (HCV) (n=1 844 882, 10.90%) accounted for >90% of the cases. The overall annual percent change (APC) in reported cases of viral hepatitis and HBV were 0.3%(95% CI −2.0 to 0.8, p=0.6) and −0.2% (95% CI −1.6 to 1.2, p=0.8), respectively, showing a stable trend. HBV rates were highest in the 20–29 year old age group and lowest in younger individuals, likely resulting from the universal HBV vaccination. The reported incidence of HCV and hepatitis E (HEV) showed increasing trends; the APCs were 14.5% (95% CI 13.1 to 15.9, p<0.05) and 4.7% (95% CI 2.8 to 6.7, p<0.05), respectively. The hepatitis A (HAV) reporting incidence decreased, and the APC was −13.1% (95% CI −15.1 to −11.0, p<0.05). There were marked differences in the reporting of hepatitis among provinces.

Conclusions

HBV continues to constitute the majority of viral hepatitis cases in China. Over the entire study period, the HBV reporting incidence was stable, the HCV and HEV incidence increased and the HAV incidence decreased. There were significant interprovincial disparities in the burden of viral hepatitis, with higher rates in economically less-developed areas. Vaccination is important for viral hepatitis prevention and control.

Keywords: hepatitis, epidemiology, screening, prevention

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The latest comprehensive description of trends in the national and provincial reporting incidence for viral hepatitis in China since 2004 were provided.

This study highlighted the magnitude and importance of viral hepatitis in China and provided key data to help determine where efforts need to be focused.

We analysed the age distributions among different types of viral hepatitis and provided the prevalence characteristics of viral hepatitis in China.

Since the study collected data from across almost the whole country, heterogeneity across reporting centres existed, which might be a weakness.

Introduction

Viral hepatitis is an important challenge to public health globally. In 2013, the greatest number of deaths and disability-adjusted life years attributable to viral hepatitis occurred in East and South Asia, including China.1 According to the WHO, approximately 100 million people in China—that is 1 in 13 people—live with chronic hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) infections.2 In 2016, the WHO approved the first global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis, with the goal of eliminating viral hepatitis as a major public health threat by 2030.3 To achieve this goal, a review of the current status of viral hepatitis and the different types was essential. Age distribution is important for obtaining a clear understanding of changing trends in viral hepatitis reporting and its future burden. China is a vast and diverse country with 32 provinces, and province-level data are also required for effective disease prevention, control and management. Therefore, the present study examined the reported rates of newly diagnosed cases of viral hepatitis and documented temporal trends across age groups and provinces.

Materials and methods

In 2004, the Chinese government established a centralised web-reporting system for notifiable infectious diseases and public health emergencies. The fundamental database for this project was maintained by the Chinese Communicable Disease Control (CCDC). A standardised case reporting form was established for the collection of demographic and diagnostic information for each case of a reportable diseases (online supplementary appendix table 1).

bmjopen-2018-028248supp001.pdf (53.2KB, pdf)

We collected data for viral hepatitis between 2004 and 2016 from the CCDC Centre’s website (http://www.chinacdc.cn/).4 5 and the Yearbooks of Health for the People’s Republic of China.6 In the system, cases were defined with diagnostic criteria issued by the law on the prevention and control of infectious diseases of the People’s Republic of China in 2004. (online supplementary appendix table 2). In this system, the reported cases numbers and the rates among the total population were provided, and we calculated the total population number each year accordingly. Based on patient histories, clinical manifestations, and laboratory test results, cases were categorised as hepatitis A, B, C, E and unidentified hepatitis.7 In this study, unidentified hepatitis cases were excluded. For the provincial analyses, Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan were not included in this research. The data were collected from the notifiable infectious disease reporting database, which is open and available to the public, and no specific permissions were required. The conduct of this study was consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki.

bmjopen-2018-028248supp002.pdf (84KB, pdf)

Incidence (per 100 000) was defined as the number of annual newly diagnosed cases divided by the population size. In this surveillance system, the cases were newly diagnosed rather than new infections. To avoid misunderstanding, we used the reported incidence in this research.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive epidemiological methods were used to examine and analyse the reported data. The annual percent change (APC), average APC and 95% CIs were calculated for viral hepatitis overall and for individual categories of viral hepatitis (A, B, C and E). Additionally, we investigated trends and made comparisons among different provinces by a heatmap analysis. For age distributions, cases were divided annually into 10 groups for each category of viral hepatitis. Joinpoint regression models were used to describe temporal trends in the reporting of newly diagnosed cases. In describing trends, we used the terms ‘increase’ and ‘decrease’ when the slope (APC) was significant (two-tailed p<0.05). The term ‘stable’ refers to a non-significant APC (p≥0.05) and indicates that the incidence was maintained at a perennially stable level. The R language V.3.3.0 and Joinpoint V.4.6.0.0 (April 2018, IMS, https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/) were used for the analyses in this study. The conduct of this study was consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in developing the research question or the outcome measures, and no patients were involved in the design, recruitment and conduct of the study. The data were collected from the online reporting system, and patients were anonymous. We were unable to disseminate the results of the research directly to study participants.

Results

National and provincial reporting incidence of viral hepatitis

National reporting incidence

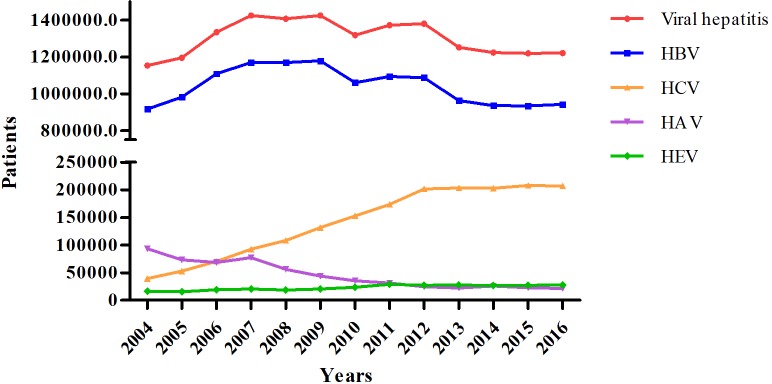

Between 2004 and 2016, a total of 16 927 233 newly diagnosed cases of viral hepatitis were reported in China. HBV (n=13 543 137, 80.00%) and HCV (n=1 844 882, 10.90%) jointly accounted for over 90% of cases. The remaining cases consisted of the following: 595 982 (3.52%) cases of hepatitis A (HAV) and 300 505 (1.78%) cases of hepatitis E (HEV) (figure 1). The total population and the definite number of reported viral hepatitis in total and different categories were provided. (online supplementary appendix table 3)

Figure 1.

Reported cases of total viral hepatitis and its different categories. HAV, hepatitis A; HBV, hepatitis B; HCV, hepatitis C; HEV, hepatitis E.

bmjopen-2018-028248supp003.pdf (169KB, pdf)

Viral hepatitis reporting incidence increased from 85.49/100 000 in 2004 to 108.44/100 000 in 2007 (p<0.05). After 2007, there was a significant decrease to 89.11/100 000 in 2016 (p<0.05). Overall, the APC was 0.3% (95% CI −2.0 to 0.8, p=0.6), indicating a stable trend. (online supplementary appendix figure 1.1)

bmjopen-2018-028248supp004.pdf (423.3KB, pdf)

The reporting incidence for HBV increased from 2004 (67.96/100 000) to 2009 (88.82/100 000) and then decreased in 2016 (68.74/100 000). From 2004 to 2007, the APC was 10.3% (95% CI 4.1 to 16.9, p<0.05), while from 2007 to 2016, the APC was −3.5% (95% CI −4.5 to −2.5, p<0.05). Overall, the APC of HBV was −0.2% (95% CI −1.6 to 1.2, p=0.8), indicating a stable trend (online supplementary appendix figure 1.2).

The reporting incidence for HCV increased from 2004 (2.92/100 000) to 2016 (15.09/100 000). From 2004 to 2007, the APC was 34.4% (95% CI 27.7 to 41.3, p<0.05), indicating a significant increase. Thereafter, the APC from 2007 to 2012 was 15.9% (95% CI 13.6 to 18.2, p<0.05), indicating a significant but slow increase, and from 2012 to 2016, the APC was 0.1% (95% CI −1.5 to 1.7, p=0.9), indicating a stable trend. Overall, the APC was 14.5% (95% CI 13.1 to 15.9, p<0.05), indicating an increased trend (online supplementary appendix figure 1.3).

For HAV, the reporting incidence decreased from 2004 (6.94/100 000) to 2016 (1.55/100 000). The APC for the entire period was −13.1% (95% CI −15.1 to −11.0, p<0.05) (online supplementary appendix figure 1.4). For HEV, the reporting incidence increased from 1.22/100 000 in 2004 to 2.18/100 000 in 2011, with an APC of 8.1% (95% CI 5.2 to 11.0, p<0.05). From 2011 to 2016, the reporting incidence decreased to 2.04/100 000, and the APC was stable (0.3%; 95% CI −3.4 to 4.1, p=0.9). Overall, the APC for HEV was 4.7% (95% CI 2.8 to 6.7, p<0.05), indicating an increasing trend (online supplementary appendix figure 1.5).

Detailed information of the joinpoint analysis results are provided in online supplementary appendix table 4.

bmjopen-2018-028248supp005.pdf (48.5KB, pdf)

Reporting incidence in relation to age

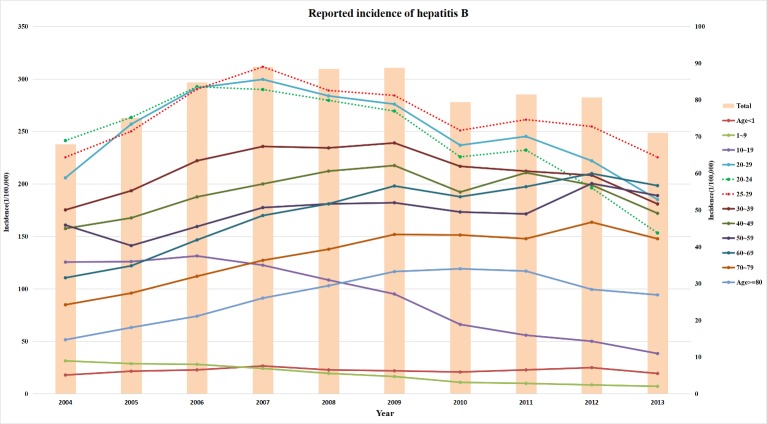

Marked differences in the reporting incidence of HBV were evident among the various age groups. Overall, the HBV reporting incidence was highest in the 20–29 year old age group. When subdivided into 20–25 and 26–29 year old age groups, the highest incidence was in the 26–29 year old group. The lowest reporting incidence of viral hepatitis occurred in the age group between 1 and 9 years old. In terms of trends from 2004 to 2013, the age groups<1, 30–39 and 40–49 were stable, while the age groups 1–9, 10–19 and 20–29 decreased. The reporting incidence for all subjects over the age of 50 increased. More recently (beyond 2007), most age groups showed a significant decrease or stable trend; however, the trend increased in the ‘50–59’ age group. (figure 2)

Figure 2.

Reported incidence of hepatitis B from 2003 to 2013.

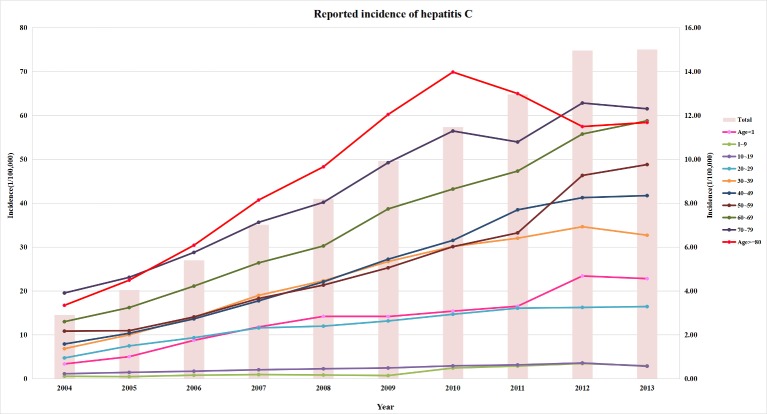

For HCV, aside from the <1 year old age group, the reporting incidence in the different age groups increased with age. The highest reporting incidence was in those >80 years old and the lowest was in those between 1 and 19 years old. From 2004 to 2013, each age group showed an increasing trend, but more recently (beyond 2011) rates were stable in the 10–19, 30–39 and 30–49 age groups. (figure 3)

Figure 3.

Reported incidence of hepatitis C from 2003 to 2013.

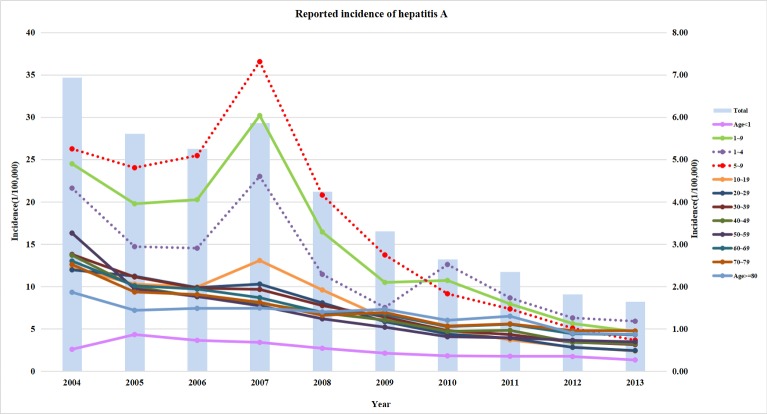

For HAV, the highest reporting incidence was in the 1–9 age group, with incidence in the 5–9 age group higher than that in the 1–4 age group. The lowest reporting incidence was in the <1 age group. In terms of trends, incidence in the 5–9 age group was stable, as was that in the 10–29 age group after 2007. All other age groups showed decreasing trends during this period. (figure 4)

Figure 4.

Reported incidence of hepatitis A from 2003 to 2013.

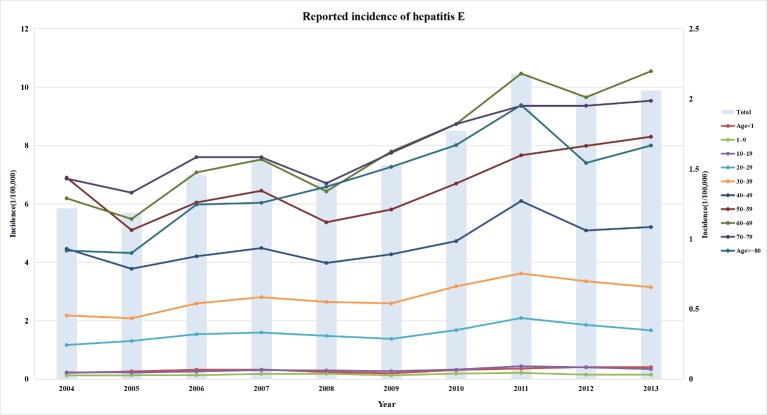

For HEV, the highest reporting incidence was in the relatively older age group (60–79 years). Aside from the 1–9 age group, where the incidence was stable, and the ≥80 age group, where the incidence decreased after 2011, the other age groups showed increasing trends during this period. (figure 5)

Figure 5.

Reported incidence of hepatitis E from 2003 to 2013.

More detailed information is provided in online supplementary appendix table 5.

bmjopen-2018-028248supp006.pdf (118.3KB, pdf)

Provincial incidence

In 2015, an analysis of the reporting incidence for viral hepatitis demonstrated that Xinjiang was the province with the highest rates (>200/100 000). Qinghai, Hainan, Guangdong, Shanxi, Fujian, Hubei, Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, and Hunan provinces had intermediate rates (>100 and<200/100,000), while Shanghai, Heilongjiang, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Tianjin, Beijing had the lowest rates (<50/100,000). Specific analyses for HBV and HCV by province are provided in online supplementary appendix figure 2.

bmjopen-2018-028248supp007.pdf (229.8KB, pdf)

To document trends in the reporting incidence for viral hepatitis from 2004 to 2015 by province, data and a heatmap of reporting incidence for viral hepatitis in general as well as for the different viruses are provided in online supplementary appendix figure 3,4. For most provinces, reporting incidence for HAV decreased, while those for HCV increased. Most northern areas of China (Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang) had a decreasing incidence of HEV, while the other provinces (Jiangxi, Shandong, Hubei, Guangxi, Hainan, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan) revealed increasing trends.

Discussion

Viral hepatitis is a significant global public health issue, and it is responsible for an estimated 1.4 million deaths per year from acute infection, hepatitis-related liver cirrhosis and cancer. Of those deaths, approximately 47% are attributable to HBV, 48% to HCV and the remainder to HAV and HEV infections.1 In 2015, an estimated 257 million people were living with chronic HBV infections and 71 million with chronic HCV infections.8 China’s hepatitis burden is the highest in the world. According to the WHO, one-third of the world’s 240 million people living with chronic HBV live in China, while approximately 7% of the world’s 130–150 million people living with HCV live in China.2

In this study, HBV reporting incidence was lowest in children under 10 years of age and highest in the 20~29 age group. Similar results have been reported previously.9 Further analysis of the 20–29 age group revealed that those 25–29 years of age (ie, born in 1975–1988) had a significantly higher reporting incidence than the 20–24 age group, suggesting a possible vaccine effect (online supplementary appendix table 6). Indeed, the HBV vaccine was first introduced into China in 1985 and integrated into the National Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) in 1992.10 Thus, the majority of individuals in the 25–29 age group were born in a period without HBV vaccine protection and were thus susceptible to transmission via the maternal-infant route. Of note, HBV reporting in individuals older than 50 years old showed an increase from 2004 to 2013. This could be explained by the following: (1) elderly individuals may be more likely to establish contact with the healthcare system. (2) There is a higher prevalence of chronic HBV and therefore a greater likelihood of presenting with complications, such as portal-hypertensive bleeding, encephalopathy, ascites, jaundice or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), leading to a diagnosis of HBV-related disease. (3) Elderly individuals engage in high-risk behaviours such as sexual contact, invasive medical procedures and sharing shavers and towels, which are all important HBV transmission routes in adults. (4) Older individuals do not have vaccine protection when they were young, and they are be more easily infected with HBV compared with successfully vaccinated children. To decrease the prevalence of HBV, vaccination among people aged 15–59 years should also be conducted.11

bmjopen-2018-028248supp010.pdf (13.3KB, pdf)

Regarding HCV, the reporting incidence increased with age; the lowest incidence occurred in children and adolescents, while the highest incidence was documented in the ≥80 age group. However, from 2004 to 2013, the reporting incidence increased in all age groups, which likely reflects increasing disease awareness, an increase in older individuals seeking medical care, increases in new infections, progression to complications of cirrhosis and providing HCV testing to a new generation.8 12 13 Notably, in China, the implementation of HCV screening for blood donors and blood products occurred in 1993,14 and a decline in transfusion-related HCV, from 72% to 47%, was associated with this intervention.13 However, relatively high rates of HCV infections among patients undergoing haemodialysis and other invasive therapies and engaging in high-risk sexual behaviours remain a potential source for HCV transmission.15 While the success achieved with recent directing antiviral agents for chronic HCV predict further declines in HCV reporting, complete eradication of HCV might not be possible without an effective vaccine.16

Provincial analyses demonstrated large differences in the reporting incidence for viral hepatitis in various provinces. Specifically, Xinjiang and Qinghai provinces had the highest incidence of viral hepatitis in general and HBV and HCV in particular, while incidence was lowest in Shanghai, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Tianjin and Beijing. These findings suggest that viral hepatitis is more prevalent in less economically developed areas, where healthcare resources and awareness of public health are suboptimal.

During this period, for HAV, the highest reported incidence was found in the 1–9 age group. For HEV, the highest reported incidence was in the older age groups (age between 60 and 79 years), similar to Ren’s research.17 A heatmap analysis of changing trends within the provinces documented that HAV reporting decreased. This finding likely reflects the impact of effective HAV vaccination (a live attenuated HAV vaccine was introduced in 1992 and incorporated into the EPI in 2008).18 Regarding the reporting incidence for HCV and HEV in most provinces, the increased trends might be ascribed to a lack of effective vaccines, more widespread application of HCV testing, and more sensitive and specific HEV diagnostics.19 Also potentially important is the increased insurance coverage and patient reimbursement programme in China, resulting in the increased exposure of large segments of the population to the healthcare system.20 Indeed, between 2003 and 2011, insurance coverage increased from 30% to 96%, and physical access to health services was achieved for 83% of the general population.

There are certain limitations to this study that warrant emphasis. First, protocols were not in place to evaluate data quality and consistency across reporting centres. Second, it is unknown which and when certain diagnostic tests were introduced into the various laboratories throughout the country. Third, the distinction between acute and recently identified chronic infections was difficult and, in some cases, not possible. Fourth, certain demographic characteristics were not provided in the electronic system; therefore, trends in sex reporting could not be ascertained.

In conclusion, this study underscores the magnitude of viral hepatitis reporting in China. Overall, the reporting of new cases of viral hepatitis and HBV has been stable. HBV continues to be the most commonly reported hepatotropic virus, but the minimal reporting in the young underscores the value of the HBV vaccine. Similarly, HAV, which mainly occurred in children and adolescents, decreased with the introduction of the HAV vaccination. HCV and HEV cases was relatively higher among elderly individuals and increased during the study period. Thus, for these viruses, increased awareness and effective vaccines are urgently needed.

bmjopen-2018-028248supp008.pdf (54.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028248supp009.pdf (13.3KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the physicians, doctors and the staff of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) for their work on data collection. The authors also wish to thank Professor Fujie Xu, Division of Viral Hepatitis, National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHHSTP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, USA and Dr Lan Zhang, Gilead Sciences Shanghai Pharmaceutical Technology Company, China, for helpful comments and valuable suggestions. All authors have no association that might pose a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Contributors: MZ was the first author. MZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript and collected data at the study site. RW, HX assisted MZ in running the study and interpreting the data. JU and RG contributed to the manuscript discussion. XW and QJ contributed to the data collection. MYG and MHN contributed to the data analysis and interpretation and performed major revisions of the manuscript. YG advised on the study design and contributed to the manuscript discussion. The corresponding author JN designed and organized the study, had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision on content and publication submission.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project [2014ZX10002002], the Program for JLU Science and Technology Innovative Research [No. 2017TD-08] and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [No. 2017TD-08].

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2016;388:1081–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30579-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Up to 10 million people in China could die from chronic hepatitis by 2030 – Urgent action needed to bring an end to the ‘silent epidemic’. http://www.wpro.who.int/china/mediacentre/releases/2016/20160727-china-world-hepatitis-day/en/ (accessed 15 Jan 2018).

- 3. World Health Organization. Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2006-2021. 2016. http://www.who.int/hepatitis/strategy2016-2021/ghss-hep/en/ (accessed: 30 Aug 2016).

- 4. China Center for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/jkj/s3578/new_list.shtml (accessed 15 Jun 2017).

- 5. The Public Health Science Data Center. http://www.phsciencedata.cn/Share/edtShareNew.jsp?id=39104 (accessed Sep 15 2018).

- 6. National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China, Health and family planning statistical yearbook of China, Beijing. 2016.

- 7. The national health and family planning commission of the People’s Republic of China. Diagnostic criteria for infectious diseases regulated by the law on the prevention and control of infectious diseases of the People’s Republic of China. 2004.

- 8. World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report, 2017. http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global-hepatitis-report2017/en/ (accessed 30 Sep 2017).

- 9. Yan YP, Su HX, Ji ZH, et al. Epidemiology of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in China: Current Status and Challenges. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2014;2:15–22. 10.14218/JCTH.2013.00030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen Y, Zheng H WF, et al. The Seroepidemiological Study and Vaccination Status Analysis on Viral Hepatitis B among Population Aged 1-59 Years in Six Areas of China in 2006. Chinese Journal Of Vaccines And Immunization 2012;18:14–18 https://dwz.cn/Z3fcEUzM. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang G, Miao N, Zheng H, et al. Incidence by age and region of hepatitis B reported in China from 2005 to 2016. Chinese Journal Of Vaccines And Immunization 2018;24:121–6 https://dwz.cn/xK6lJZ6U. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duan Z, Jia JD, Hou J, et al. Current challenges and the management of chronic hepatitis C in mainland China. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014;48:679–86. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rao H, Wei L, Lopez-Talavera JC, et al. Distribution and clinical correlates of viral and host genotypes in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:545–53. 10.1111/jgh.12398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cui Y, Jia J. Update on epidemiology of hepatitis B and C in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;28(Suppl 1):7–10. 10.1111/jgh.12220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Qin Q, Smith MK, Wang L, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in China: an emerging public health issue. J Viral Hepat 2015;22:238–44. 10.1111/jvh.12295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bartenschlager R, Baumert TF, Bukh J, et al. Critical challenges and emerging opportunities in hepatitis C virus research in an era of potent antiviral therapy: Considerations for scientists and funding agencies. Virus Res 2018;248:53–62. 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ren X, Wu P, Wang L, et al. Changing Epidemiology of Hepatitis A and Hepatitis E Viruses in China, 1990-2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23:276–9. 10.3201/eid2302.161095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fangcheng Z, Xuanyi W, Mingding C, et al. Era of vaccination heralds a decline in incidence of hepatitis A in high-risk groups in China. Hepat Mon 2012;12:100–5. 10.5812/hepatmon.4907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang Q, Tang G, Liu H, et al. [Investigation on the causes of increased hepatitis E cases reported in Guizhou province]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2015;36:228–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meng Q, Xu L, Zhang Y, et al. Trends in access to health services and financial protection in China between 2003 and 2011: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;379:805–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60278-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028248supp001.pdf (53.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028248supp002.pdf (84KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028248supp003.pdf (169KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028248supp004.pdf (423.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028248supp005.pdf (48.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028248supp006.pdf (118.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028248supp007.pdf (229.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028248supp010.pdf (13.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028248supp008.pdf (54.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028248supp009.pdf (13.3KB, pdf)