Abstract

Objectives

To apply and evaluate dementia-friendly community (DFC) principles in prisons.

Design

A pilot study and process evaluation using mixed methods, with a 1-year follow-up evaluation period.

Setting

Two male prisons: a category C sex offender prison (prison A) and a local prison (prison B).

Participants

68 participants—50 prisoners, 18 staff.

Intervention

The delivery of dementia information sessions, and the formulation and implementation of dementia-friendly prison action plans.

Measures

Study-specific questionnaires; Alzheimer’s Society DFC criteria; semi-structured interview and focus group schedules.

Results

Both prisons hosted dementia information sessions which resulted in statistically significant (p>0.05) increases in attendees’ dementia knowledge, sustained across the follow-up period. Only prison A formulated and implemented a dementia action plan, although a prison B prisoner dedicated the prisoner magazine to dementia, post-information session. Prison A participants reported some progress on awareness raising, environmental change and support to prisoners with dementia in maintaining independence. The meeting of other dementia-friendly aims was less apparent. Numbers of older prisoners, and those diagnosed with dementia, appeared to have the greatest impact on engagement with DFC principles, as did the existence of specialist wings for older prisoners or those with additional care needs. Other barriers and facilitators included aspects of the prison institution and environment, staff teams, prisoners, prison culture and external factors.

Conclusions

DFC principles appear to be acceptable to prisons with some promising progress and results found. However, a lack of government funding and strategy to focus action around the escalating numbers of older prisoners and those living with dementia appears to contribute to a context where interventions targeted at this highly vulnerable group can be deprioritised. A more robust evaluation of this intervention on a larger scale over a longer period of time would be useful to assess its utility further.

Keywords: dementia, prisoner health, older prisoners, peer support, environment, awareness raising

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study published exploring the applicability of dementia-friendly community principles in prisons that we have found, and is one of the only studies published worldwide to evaluate the support and/or management of prisoners living with dementia.

The patient and public involvement component of the study was invaluable in establishing the need for dementia-focused work, targeting the intervention and preparing study materials.

Involving people with dementia and their families in the intervention was particularly difficult to achieve in a prison context.

The relatively small sample size coupled with high prisoner and personnel turnovers made quantitative analysis challenging, and conducting the study in male prisons only is a limitation.

The number of participants interviewed and involved in focus group discussions provided a rich set of data to explore findings.

Introduction

People in prison are reported to age more rapidly due to their lifestyles, healthcare access, substance misuse and the stress of imprisonment. Thus, whilst the definition of ‘older prisoner’ varies, it is typically considered to be at least 10 years younger than that of the general population1. The number of prisoners over the age of 50 in England and Wales has tripled since 2002, and now represents 16.3% of the overall prison population.2 This is projected to rise further in future.3 4 Health problems and social care needs are reportedly extensive among this group, estimated to affect over 85% of older prisoners, which has been associated with an approximately threefold increase in the financial costs of accommodating them compared with the ‘general’ prisoner population.5–9 The number of prisoners diagnosed with dementia specifically is unknown, but is at least commensurate with community levels, although likely to be much higher due to the poorer health and lifestyles of prisoners, and the effects of a prison system built for younger, fitter prisoners.5 6 10–13 Additionally, people living with dementia in prisons may have harsher prison experiences than their more cognitively able counterparts, which can exacerbate their symptoms, as they are more likely to be vulnerable to victimisation, isolation, and punishment for failing to ‘comply’ with prison routines.6 11 14–18 It is a matter of national policy that prisons provide a standard of care equivalent to that in the community,19 20 but a recent parliamentary inquiry has stated that despite some areas of good practice, the government is failing in its duty of care to prisoners in England and Wales.21

Dementia has become a health and social care policy priority in the UK, with the governments’ dementia strategy promoting the establishment of dementia-friendly communities (DFCs),22 23 defined as places ‘where people with dementia are understood, respected and supported’.23 (p1) Key DFC principles include: the empowerment and involvement of people with dementia in the formation and development of communities, increased dementia awareness, challenging stigma, timely access to care, and supportive social and physical environments.24 Evaluations of DFCs in UK communities mostly reported increases in dementia awareness, but progress on social and environmental change varied and the involvement of people living with dementia were limited in the short-term.25–31 There have been no published evaluations that we have found applying DFC principles in prisons in England and Wales, nor of any other intervention targeted at people living with dementia in prisons internationally.32 33 Given the human rights and financial concerns surrounding the imprisonment of people with dementia,13 34–36 it seems imperative to explore, implement and evaluate programmes focused on supporting this highly vulnerable population.

Research aims

This study aimed to explore the application of the Alzheimer’s Society (AS) Dementia Friendly Community principles to two prisons. The research questions were:

What progress was made towards applying DFC principles at each prison, following an intervention comprised of information sessions and meetings with the AS?

What was the impact of the intervention?

What contextual factors affected implementation of the intervention and DFC principles?

Method

Study design

The research was structured as a small-scale pilot study and process evaluation, employing a mixed methods design, with a 1 year follow-up period. It was conducted in three stages:

Patient and public involvement (PPI) (prisoner involvement in the research process itself, as distinct from being a ‘participant’ in interventions or evaluations: "research being carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ members of the public rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them’37): the involvement of prisoners in the research process was essentially preparatory, establishing the need for dementia-related interventions at each prison, identifying the people and site for the intervention, and assisting in modifying evaluation materials; actions arising from this involvement were relayed to the prisoners. Prisoners were not directly involved in delivering the intervention, recruiting participants nor conducting the evaluation. Prisoner involvement was not formally evaluated, and so no further findings are reported from this stage of the study.

Intervention: delivery of hour-long Dementia Friends AS information sessions (https://www.dementiafriends.org.uk/WEBRequestInfoSession), and meetings between prison staff and AS to plan and implement DFC-led alterations.

Evaluation: of the information session, of progress towards implementing DFC principles, and of contextual factors affecting their application, using questionnaires pre-information session and post-information session and at follow-up, and individual interviews and focus groups at follow-up.

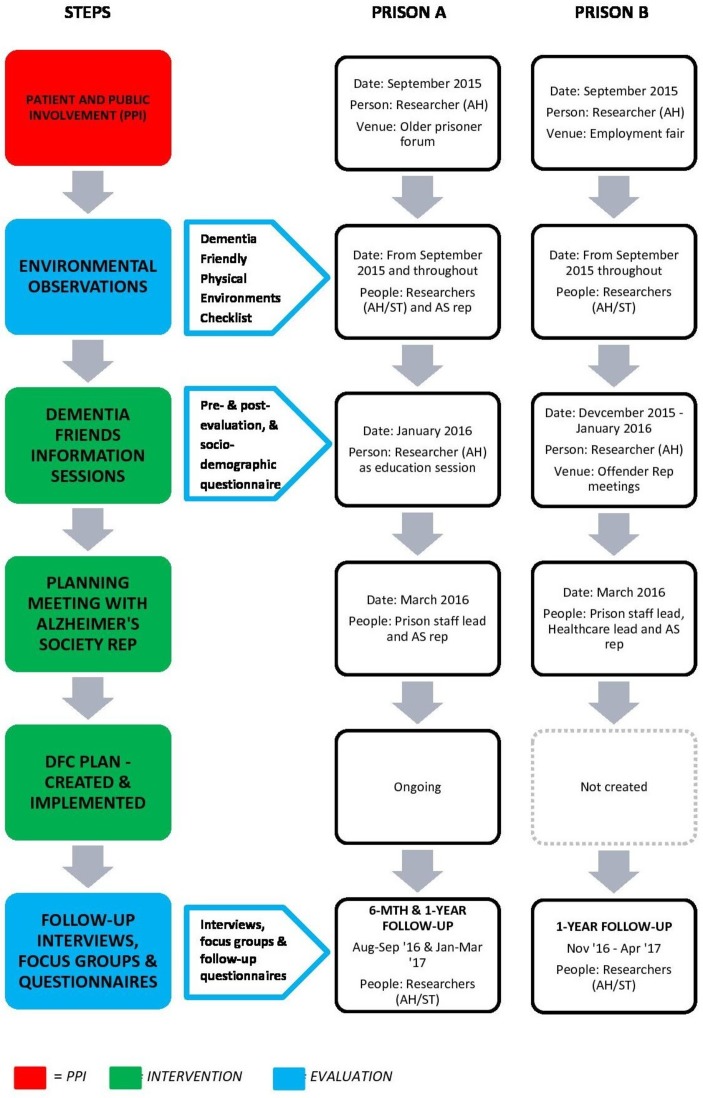

The sequencing of these three stages across the study are shown in figure 1:

Figure 1.

Steps involved in the study.

Context

This study was conducted in two prisons in the East of England. Prison A was a category C sex offender prison with 34.2% of the population aged over 50,38 and two opt-in 120 bed wings for older prisoners (aged >60 years) which had had some adaptation (stair lifts, quiet room). There was also a prison-wide policy for older prisoners to be unlocked through the day. There were reportedly between zero and four prisoners diagnosed with dementia across the course of the study. Prison B was predominantly a local prison (which serve the courts local to the prison, holding prisoners: on remand, serving shorter sentences, and serving longer sentences awaiting allocation to another prison). 16.1% of Prison B's population was over 50,39 and it had a 26-bed wing for older prisoners. In addition, there was a 15-bed palliative and significant social care needs wing, with environmental adaptations (normalised dining area, hospital-type beds), which reportedly held five prisoners diagnosed with dementia at follow-up, and ran a cognitive stimulation group. This prison also had 24 hours healthcare staff and an inpatient wing. Both prisons had some prison-wide activities focused on older prisoners (such as dedicated gym/library sessions).

Participants

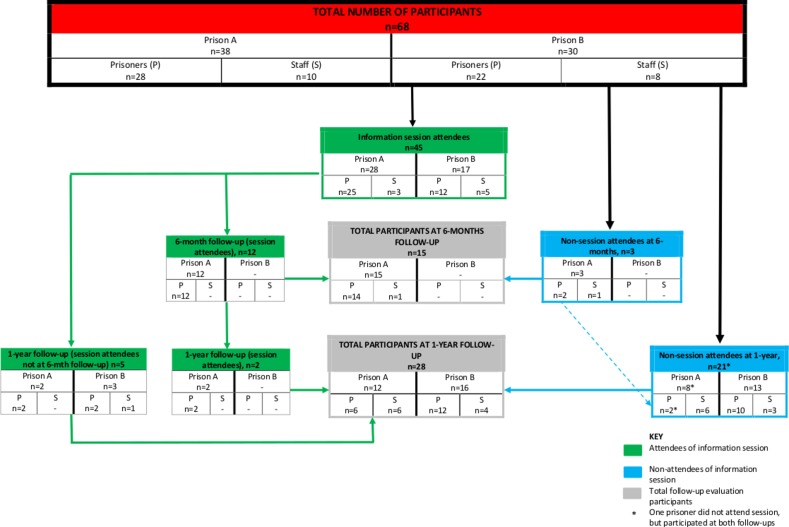

Forty-six prisoners were involved in the PPI phase of the study (16 from prison A and 30 from prison B). A total of 68 individuals (50 prisoners and 18 staff) participated in the intervention and evaluation stages of the study, as detailed in figure 2:

Figure 2.

Flow of participants through the intervention and evaluation stages of the study.

Forty-five individuals (37 prisoners and eight staff) attended information sessions, invited by the staff who were leading for the study within each prison, as selected by each prisons’ No 1 Governor. Invitations were extended to those likely to be involved in supporting people with dementia at the prisons and included: older prisoners, prisoner peer supporters and staff working on specialist (older prisoner or health-oriented) wings. Information session attendees were also asked for their consent to be approached to participate in the follow-up evaluation, and were invited to do so by researchers and prison staff leads. Twelve attendees (all prisoners) from prison A participated at 6 months, and a total of seven attendees (6 prisoners and one staff member) from both prisons participated at 1-year follow-up. Only two attendees participated at both 6-month and 1-year follow-up, both prisoners.

The remaining 23 follow-up evaluation participants (13 prisoners and 10 staff) who did not attend the information sessions, were composed of prison staff who led on or participated in the intervention implementation at the prisons (who were invited to take part in the evaluation by the research team), and of additional prisoner peer supporters and prison officers who were interested in dementia at the prisons (who were invited by the prison staff leads). One person with dementia participated in PPI at prison A, but none were involved in the evaluation, as far as we were aware. The reasons for this are somewhat unclear, as the research team was not directly involved in recruiting prisoners.

Materials

Information sheets and consent forms were developed by the research team and modified according to National Offender Management Service specification. The rest of the materials used were:

AS Foundation Criteria for the Dementia-Friendly Communities Recognition Process.40

Socio-demographic questionnaire (gender, age, education level, marital status, race, children, religion, politics).

Study-specific Information Session Evaluation questionnaire developed by the research team, and modified following prisoner feedback. The questionnaire contained open and closed questions on knowledge, learning and confidence regarding dementia (see online supplementary file 1).

Study-specific Dementia Friendly Prisons Aims questionnaire, developed by the research team, based on the key DFC principles24 (see online supplementary file 2).

The ‘Dementia Friendly Physical Environments Checklist’.41

Semi-structured interview schedules and focus group frameworks formulated by the research team, focused on the information session, support and barriers for people with dementia, and prison dementia friendliness.

bmjopen-2019-030087supp001.pdf (80.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030087supp002.pdf (68.9KB, pdf)

Procedures

As shown in figure 1, both prisons facilitated PPI activities, and hosted dementia information sessions at which pre-session and post-session evaluation questionnaires were collected. Due to sessions over-running, there were difficulties collecting the socio-demographic questionnaire at prison A. Both prisons’ study leads met with AS representatives, but only Prison A created and implemented DFC plans, at which a 6-month interim follow-up occurred due to rapidly falling numbers of information session attendees. A full 1-year follow-up was conducted at both prisons.

At both follow-up points, evaluation and dementia aims questionnaires were collected, and interviews and focus groups conducted. Across the follow-up evaluation, 11 interviews were conducted with prison staff at suitable locations within and outside of the prison, and six with prisoners during legal visits. All interviews were taped, and one staff interview was scribed by a researcher. A further 24 prisoners participated in focus groups, which were documented on flip chart paper as permission to tape had not been sought in time. In addition, AS representatives (workers identified by AS to work with the prisons for this study) were interviewed, and were invited to do so by the researchers. Prisoners were selected for interview based on the type of peer supporter role they occupied: those providing direct care assistance to people with dementia (eg, care support orderlies, wheelchair pushers), those providing indirect assistance as a secondary part of their roles (such as library assistants) and prisoner representatives (who represent the views of prisoners at meetings with prison management). The remaining prisoners participated in focus groups.

Informed consent was sought from all participants prior to interviews or focus groups, with researchers going through information sheets and consent forms with potential participants, answering any questions that arose.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis

The data were extracted from the questionnaires by a researcher (ST) who was not involved in the intervention, and entered onto a dataset created using SPSS V.23.42 One researcher (NDW), who was not involved in either the intervention nor data collection, conducted an independent double-check to identify any incompatible entries. Both researchers (NDW, ST) analysed the data using SPSS. Statistical analysis focused on pre- and post-session and follow-up changes using χ2, McNemar or Wilcoxan signed-rank tests (p<0.05).

Qualitative analysis

All taped interviews were transcribed verbatim which together with focus group flipcharts, were subject to a Framework Analysis.43 This approach was selected as it could accommodate differing data sources, and provided a clear and systematic structure for a team-based analysis. Using an inductive approach, all researchers: (1) read interviews and noted initial themes; (2) analysed five transcripts in-depth, noting further themes; (3) based on this created an analytical framework with main emergent themes; (4) used this framework to ‘code’ all material—two researchers independently categorised each transcript using NVivo V.1144 or MS Word45; (5) analyses were combined and summarised in an MS Excel46 spreadsheet, with differences resolved within the team; and (6) findings were interpreted.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 68 individuals (50 prisoners and 18 staff) participated in the Intervention and Evaluation stages of the study. The majority of prisoners identified as male (n=49, 98%), and one prisoner identified as transgender. Conversely, the staff sample was mostly composed of females (n=11, 79%, missing=4). The mean age of the sample was 45.3 years, and ranged from 23 to 76 years (missing=8). The mean age of the prisoner participants from prison A (50.6 years) was almost 10 years higher than the prisoner participants of prison B (40.9 years). This difference was statistically significant (t(44)=2.793, p=0.008). The overall mean age differences between prisons and between prisoners and staff were not statistically significant. With regard to the other socio-demographic variables, there were a large number of missing data making these difficult to interpret, however they have been included as online supplementary file 3.

bmjopen-2019-030087supp003.pdf (117KB, pdf)

Key findings

This section will discuss the three research questions on progress, impact and context that this study sought to answer, and present an analysis of each.

Research question 1: progress

Both prisons agreed to participate and engaged in the project and evaluation, but they differed in the extent of their engagement. Progress was measured against AS criteria40 which is summarised in table 1 for each prison.

Table 1.

Progress as measured against Alzheimer’s Society Foundation Criteria (2014)

| Criteria | Prison A | Prison B |

| 1.Create or join a Dementia Action Alliance (DAA) |

|

The prison did not join nor create a DAA or similar. |

| 2.Identify a community leader | There was a lead person liaising with the Alzheimer’s Society (AS) rep throughout. This changed several times across the study. | The identified lead met with the AS rep once, but a dementia-friendly community was not worked towards. |

| 3.Have an awareness raising plan |

|

|

| 4.Involvement of people living with dementia, and their carers |

|

Prison not working towards establishing a dementia-friendly community within this project, so no prisoner nor family or friends involved. |

| 5.Publicise the work of the community |

|

|

| 6.Focus the action plans on two or three key priorities | A dementia action plan was created focused on: raising awareness; improving the physical environment; and working with partners inside and outside the prison. | No dementia action plan was created. |

| 7.Have a 6 month and annual evaluation plan |

|

The prison participated in the research evaluation—no further evaluation plans made. |

Prison A met a number of the criteria which included joining a local Dementia Action Alliance (joined by organisations to ‘share best practice and take action on dementia’47), creating a DFC plan which was posted on the internet, running awareness raising events, and making small environmental changes—such as having planters in a specialist wing yard. Actions in these areas were reportedly ongoing although slow, and mostly implemented within the older prisoner wings:

I feel I’ve been so lucky to be involved in this project…it’s one of the few places that I’ve been where they’ve actually listened… and it’s slow, but it’s going to be slow, you just have to accept that. But, they do listen, and every time I go …something has happened in relation to what I’ve talked about previously. And that is so unique (Prison project worker)

While prison B engaged with the intervention initially (hosting information sessions and meeting with an AS representative), there was little progress beyond this, with few AS criteria met and no DFC plans created. The lack of continued engagement largely centred around there being lower numbers of older prisoners at this prison, with other issues prioritised as a result, and the belief that services for people with dementia at the prison were good enough already. A prisoner at prison B did use the information session materials to produce an edition of the prison magazine focused on dementia, and the difficulty of being in prison when family are experiencing dementia or supporting others with dementia.

Research question 2: impact

Within this study, impact was assessed using study-specific questionnaires evaluating (1) the dementia information session, and (2) whether DFC aims were met, and if changes were made by the prison to support these. As no DFC plans were made or implemented at prison B, analysis of questionnaire (2) will only be presented for prison A. Quantitative results will also be augmented by interview and focus group analyses.

Information session evaluation

Participants completed questionnaires evaluating the information session pre-session (n=45) and post-session (n=40), and at 6 months (n=12) and 1-year follow-up (n=7). This was also explored further in interviews and focus groups. Table 2 shows data taken from the questionnaires across the evaluation period.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and comparative analyses of awareness session questionnaires

| Precomparison analysis | Postcomparison analysis | Follow-up analysis | ||||

| Pre-post (n=38) |

Pre-6-month (n=12) |

Pre-1 year (n=7) |

Post-6 month (n=11) | Post-1 year (n=5) |

6-month–1 year (n=3) |

|

|

Do you know what dementia is?

(N° Yes, %; significance level)* |

31 (86.1)−36 (100) p=0.063 2 missing |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

|

How much do you know about dementia?

(median; significance/level)† |

4–7 Z=−4.594, p<0.001 1 missing |

5–6 Z=−2.831, p=0.005 |

5–6 Z=−2.232, p=0.026 |

7–6 Z=−1.311, p=0.190 |

7–4 Z=0, p=1.000 1 missing |

6–4 Z=−1.414, p=0.157 |

|

Do you know the causes of dementia?

(N° Yes, %; significance level)* |

7 (25) – 24 (85.7) p<0.001 10 missing |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

|

Do you know what a dementia-friendly community is?

(N° Yes, %; significance level)* |

13 (44.8)−26(89.7) p<0.001 9 missing |

7 (70.0)–9 (90.0) p=0.500 2 missing |

1 (16.7)–5 (83.3) p=0.125 1 missing |

9 (90.0)–8 (80.0) p=1.000 1 missing |

3 (100)–3 (100) p=1.000 2 missing |

3 (100)–3 (100) p=1.000 |

|

Did the awareness session increase your knowledge/did you learn?

(N° Yes, %; significance level)* |

n/a | n/a | n/a | 10 (100)–9 (90.0) p=1.000 1 missing |

4 (100)–4 (100) p=1.000 1 missing |

3 (100)–3 (100) p=1.000 |

|

Confidence in talking about dementia to others?

(median; significance/level)† |

5–7 Z=−3.917, p<0.001 8 missing |

5–7 Z=−0.854, p=0.393 |

5–6 Z=−1.069, p=0.285 3 missing |

7–7 Z=−1.897, p=0.058 |

7–6 Z=0, p=1.000 1 missing |

7–6 Z=0, p=1.000 |

|

Confidence in helping people living with dementia?

(median; significance/level)† |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 8–7 Z=0, p=1.000 |

|

Did the awareness session change your views on people with dementia?

(N° Yes, %; significance level)* |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 3 (100)–3 (100) p=1.000 |

=statistically significant.

=statistically significant.

*Significance testing using exact McNemar's test

†Significant testing using Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

All of the responses concerning perceived knowledge of dementia increased post-session, reaching statistical significance for level of knowledge about dementia, its causes and DFCs. Participants also reported feeling more confident talking to people with dementia post-awareness session. At 6 months and 1-year follow-up, participants continued to report that they knew more about dementia than they had pre-awareness session, differences which were statistically significant. Unsurprisingly, no results were significant for the three participants sampled at both 6-month and 1-year follow-up.

Some participants also reported that the session altered the way they supported people living with dementia in the prison, with a positive knock-on effect on those relationships. There were also reports of participants finding the information personally comforting and useful in supporting colleagues, and also extending to their communities of friends and family outside of prison:

For me it helped me mostly because my grandad suffers with dementia… for me [the information session] put my mind at ease a lot with that and helped me. And I talked with my mum and my grandma about it a lot more because of that, because I felt a bit more confident having that knowledge (prisoner)

Dementia-friendly prison aims

Table 3 shows study participants’ views on whether prison A met DFC aims at 6 months (n=15) and 1 year follow-up (n=12), using the DFC aims questionnaire. These were largely independent samples, therefore a comparative analysis was not possible.

Table 3.

Dementia-friendly prison aims and changes made to prison A

| Dementia-friendly prison aims | 6-Month follow-up (n=15) |

1-Year follow-up (n=12) |

||||||||||||||

| Aims met? | Change over last 6 months | Aims met? | Change over the last 6 months | |||||||||||||

| For better | No change | For worse | For better | No change | For worse | |||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Views of people with dementia are listened to | 5 | 33.3 | 4 | 26.7 | 6 | 40 | 3 | 20 | 3 | 25 | 3 | 25 | 6 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Good understanding of dementia among prison staff | 2 | 13.3 | 2 | 13.3 | 10 | 66.7 | 2 | 13.3 | 2 | 16.7 | 2 | 16.7 | 4 | 33.3 | 2 | 16.7 |

| Good understanding of dementia among prisoners | 5 | 33.3 | 5 | 33.3 | 8 | 53.3 | 1 | 6.7 | 2 | 16.7 | 3 | 25 | 4 | 33.3 | 1 | 8.3 |

| Accessible and appropriate prison activities for people with dementia | 4 | 26.7 | 1 | 6.7 | 11 | 73.3 | 2 | 13.3 | 3 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 58.3 | 1 | 8.3 |

| People with dementia are made to feel they can contribute to prison life | 4 | 26.7 | 3 | 20 | 8 | 53.3 | 3 | 20 | 3 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 58.3 | 1 | 8.3 |

| Staff pick up and act on early signs of dementia | 2 | 13.3 | 4 | 26.7 | 8 | 53.3 | 1 | 6.7 | 2 | 16.7 | 1 | 8.3 | 6 | 50 | 1 | 8.3 |

| People with dementia can engage fully in prison life | 6 | 40.0 | 4 | 26.7 | 8 | 53.3 | 1 | 6.7 | 4 | 33.3 | 1 | 8.3 | 7 | 58.3 | 0 | 0 |

| People with dementia are supported to live as independently as possible | 10 | 66.7 | 6 | 40 | 4 | 26.7 | 3 | 20 | 10 | 83.3 | 3 | 25 | 6 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| The prison is easy to get around for people with dementia | 4 | 26.7 | 1 | 6.7 | 8 | 53.3 | 3 | 20.0 | 4 | 33.3 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 58.3 | 1 | 8.3 |

| People with dementia are respected | 4 | 26.7 | 1 | 6.7 | 9 | 60 | 4 | 26.7 | 5 | 41.7 | 1 | 8.3 | 6 | 50 | 1 | 8.3 |

| People with dementia face stigma and discrimination here | 4 | 26.7 | 3 | 20.0 | 8 | 53.3 | 2 | 13.3 | 4 | 33.3 | 1 | 8.3 | 6 | 50 | 1 | 8.3 |

At both 6-month and 1-year follow-up, the majority of participants reported that people with dementia in the prison did not face stigma and discrimination and were supported to live independently at the prison. At 6 months, the latter was reported to have improved—the only area in which participants reported positive change across the study. It is possible that this reflects that prisons in general expect prisoners to function independently within parameters, but in addition, prison A had adopted a policy of ‘enablement’, which appears to be compatible with this DFC aim:

I’m forever saying ‘enable’, enable as much as possible. Encourage them to clean, encourage them to tidy their cell up… get them doing as much as possible. [Person with dementia], for all the will in the world you couldn’t take work away from him, he just wants to do it himself…we’re never going to take that off him (prisoner)

Regarding the other DFC aims, only around a third or less of participants agreed that they had been met. This included two foci of prison A’s DFC action plan: ease of navigation, and understanding and identifying symptoms of dementia, particularly among staff. While on the one hand this may represent a lack of observable progress in these areas, it may also reflect that the dementia-focused work at prison A was largely implemented across two older prisoner wings rather than prison-wide. This was indicated by staff participants who worked on mainstream wings reporting that they were unaware of the DFC project, and also by prisoner observation:

I think those that work specifically on [older prisoner wings], I think they’re becoming more aware. But as the others, they got a very mixed bag. A very mixed bag (prisoner)

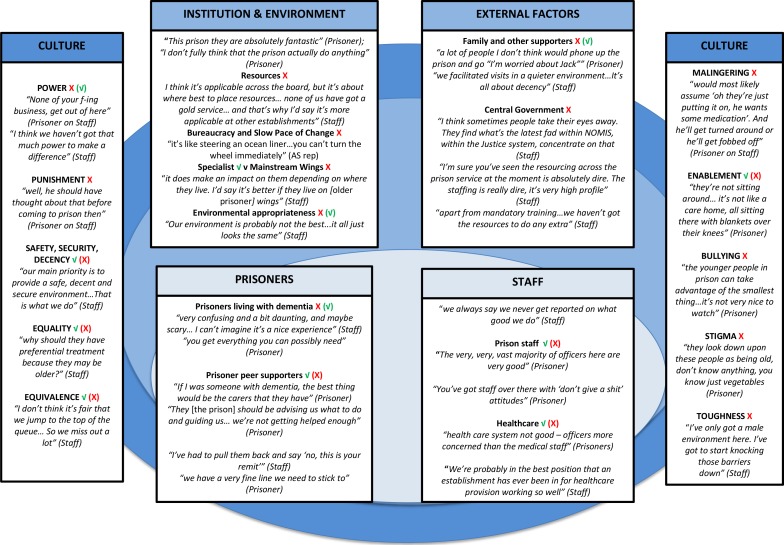

Research question 3: contextual factors

An analysis of staff and prisoner interviews and focus group discussion identified elements of the prison context which could act as barriers or facilitators to the implementation of DFC principles. These were related to: (1) institution and environment, (2) staff, (3) prisoners, (4) prison culture and (5) external factors. These are depicted in figure 3 with apposite quotations, and are discussed further below.

Figure 3.

Barriers (X) and facilitators (√) to applying dementia-friendly community principles, and their interactions.

Institution and environment

Prison budget cuts and bureaucracy were reported to impact engagement with the intervention, and implementation. Staff reported that the larger number of older prisoners and relative stability of the prisoner population at prison A justified greater engagement with the project (although this fluctuated according to numbers of prisoners with a dementia diagnosis). At prison B, staff reported that the lower numbers of older prisoners and the amount of prisoner turnover could not justify continued engagement—mental health problems and substance misuse were clearer priorities. Staff leads at this prison also reported that they felt their support of people with dementia was good enough already.

Overall, staff and prisoner opinion of the dementia friendliness of both of the prisons was mixed. Specialist wings were largely considered more suitable for people with dementia than mainstream wings, as they were considered to be safer and less isolating, with more relaxed regimes and activities. Opportunities to socialise outside of the specialist wings at prison A was considered positively, although some felt activities were too few at both prisons. Environmentally, the specialist wings were reportedly easier to navigate and more comfortable than mainstream wings. However, it was widely agreed that these fell short of dementia friendliness (eg, cell doors not wide enough for wheelchairs at prison A, and lack of stair lifts at prison B), as did the prisons overall, which were reportedly difficult to get around. Relaxed regimes, activities and adaptations were all affected by budget cuts.

Staff

There were mixed reports from prisoners and staff on prison and healthcare staff support for people with dementia in the prisons. Prison staff regularly working on specialist wings were described as more dementia aware and supportive of people with dementia, than staff working on mainstream wings. However, this more supportive practice seemed dependent on whether staff were able to choose this work. The introduction of social care at prison A and the presence of 24 hours healthcare staff at prison B were considered a potential benefit to people with dementia. There were mostly positive reports of most healthcare staff at both prisons, but there was some concern expressed about the more ‘security’ focused operation of the inpatient wing and staff at prison B. Some participants also suggested that healthcare staff seemed reluctant to make dementia diagnoses—with reports of prisoners with dementia symptoms outstripping numbers diagnosed, affecting treatment and also prison decisions to engage with dementia-related interventions.

Prisoners

Reports of the experiences of people with dementia at both prisons varied, but most participants suggested that it was likely to be confusing or frightening. Peer supporters providing direct care support for those with dementia were considered to provide vital support at prison A—possibly as a result of less healthcare cover. The number of peer supporters at both prisons were seen as too few by most participants, with training, support and guidance around dementia mostly reported as inadequate, and a lack of formal contracts making roles unclear at prison A. It is of note that healthcare staff were reported to offer peer supporters good informal support on one of the specialist wings at prison B.

Prison culture

There were a number of aspects of prison policy, practice and culture which appeared to be compatible with DFC principles: safety, security and decency as guiding operating goals; equality in the application of rules; equivalence of care between prisons and the community; and at prison A enablement. However, it seemed that some of these were applied patchily or too rigidly at times to be supportive, such as an expectation that all prisoners conform to rules equally irrespective of cognitive capacity, or a lack of decency in not offering through-the-night incontinence care.

Other aspects of prison culture were identified that could affect the support of people with dementia, as well as the likelihood of prisoners seeking help. These included: how the punishment of prison was perceived—prison as punishment or prison for punishment; perceptions of prisoners as potentially malingering or manipulative; a somewhat ‘macho’ culture; bullying and exploitation (although only a couple of instances were reported); and stigma about age—which seemed to have some effect on prisoners’ choice of accommodation and staff desire to work with this group. It is also of note that power relationships suffuse prison culture. Some manifestations of this reported were: fear of censure resulting in the reluctance of some peer supporters to advocate for people with dementia in the prison, and for more junior prison staff to challenge practice.

External Factors: family/friends and central government

There were a couple of examples of liaison between prison staff and family (mostly when prisoners were dying or had died), family visits facilitated in quiet spaces and the involvement of a charity that facilitated family connections at both prisons. However, there appeared to be a lack of mechanisms/policy in place to maintain links between family/friends and people with dementia in both prisons, which included assistance with telephone calls, and for family to report concerns or receive support, and some reports of other prisoners risking punishment to assist.

Central governments’ austerity-driven cuts were reported to impact the whole prison system in myriad ways. The lack of policy and strategy attention for people living with dementia appeared to amplify the effect. Given both prisons reportedly struggled with implementing mandatory operations and training, attending to issues that are not mandatory seemed to render the status of additional dementia input as a ‘luxury’ (staff).

Discussion

Summary of results

Both of the participating prisons reported that DFC principles were applicable to them, but differed in the extent to which they engaged with the intervention. Dementia information sessions were delivered at both, and reportedly increased participants’ knowledge, confidence, and understanding of dementia, consistent with community DFC evaluations.25–31 Prison A created and implemented a DFC action plan, facilitated additional awareness raising initiatives, small environmental changes and reportedly helped people with dementia to live more independently—but, progress was considered slow and was mostly focused on older prisoner wings. Prison B did not create nor implement a DFC action plan. Facilitators and barriers for the implementation of DFC principles largely flowed from where individuals living with dementia chose to reside, with older prisoner-focused wings considered more dementia friendly, with more ‘aware’ staff and peer supporters. Austerity-related cuts to prison budgets presented one of the biggest barriers to implementation and to decisions to engage in the intervention—which was also driven by numbers of older prisoners and people with dementia diagnoses.

Study strengths and limitations

Study strengths and limitations divide into those related to the fidelity of the intervention at prison A, and those related to the running of the evaluation at both prisons.

Intervention

Although most AS intervention criteria were met, one of the key DFC principles proved challenging: involving people with dementia (although this was also a difficulty for community interventions).25–31 Within this study, this appeared to be partly due to fluctuating numbers of prisoners formally diagnosed with dementia, which also affected the evaluation. Additionally, DFC plans were largely created by the prison lead alone, but a steering group including people with dementia in the prison, family, peer supporters and staff from across the prison, could establish and maintain a prison DFC more consistent with AS’s central tenets. The AS did not ‘train’ prisoners as Dementia Champions as part of this project. Overcoming bureaucratic obstacles to doing so would also be more consistent with DFC principles.

Evaluation

This is the first published evaluation of the government-endorsed DFC approach to prisons, and—as a small-scale study—was essentially exploratory, taking place in only two prisons and with no control groups. The PPI phase of the study proved valuable in targeting the work and ensuring materials were workable, although an expanded role for prisoner involvement in design, recruitment and execution would have been desirable. The sample size for the information session evaluation was relatively small, and significantly reduced across the follow-up period affecting sub-group analyses, as did the lack of socio-demographic data. A ‘traditional’ 1-year follow-up study of a prison-based intervention may be impossible on a small-scale due to high prisoner and staff turnover—larger sample sizes, or briefer follow-up periods may be more feasible.

Implications and recommendations

The biggest challenge to the implementation of DFC principles in both prisons seemed to come from the significantly reduced budgets allocated since 2010, resulting in a quarter of the prison workforce being cut,48 49 and contributing to record levels of prisoner violence and self-harm.50–53 As older prisoners typically pose less problems and reoffend less than their younger counterparts,54–57 their difficulties are in danger of going unrecognised, underscored by the government’s repeated refusal to create a strategy focused on them.17 58–63 Centralised resources and strategy are fundamental in the early release of people living with dementia in prison, which is currently rarely used, in guiding and funding better health and social care, and more appropriate social and physical environments. However, from the evaluation there were a number of more locallycontrolled practices identified that could facilitate DFC practice, some of which could be co-designed and delivered with external organisations:

Partial segregation of older prisoners on wings that are ‘opt-in’ for both prisoners and staff, with trained and supported staff and peer supporters,62 a comprehensive programme of activities, and opportunities for prisoners to leave the wing to access prison-wide activities and services if desired.64 65

Dementia information sessions made available to the wider prison, to include a reflection of the impact of prison and its culture on people with dementia, and examples of good prison dementia practice from specialist wings or health/social care.

Policies for older prisoners and those with dementia which allow them to be unlocked, to receive retirement pay commensurate with working peers’ pay and to access appropriate activities—potentially at an off-wing centre.

Use of in-house expertise, labour and adaption of simple DFC design to improve environments.66–68

Access to specialist dementia training for healthcare staff where needed, and a clear referral pathway to specialist dementia services in the community. Dementia awareness could be included as part of broader health promotion activities.

Review and translate local policies, practices and procedures for older prisoners and people with dementia, including disciplinary and restraint procedures. Resultant training can address more problematic aspects of prison culture, including stigma, bullying and malingering assumptions—linked as they are to prison suicide.69

To systematically support the links between people living with dementia in prison and their family to be more in line with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines.70 For example, to assist telephone calls, facilitate travel to visits in quiet spaces, increase liaison between family/friends and the prison, and support family and friends in coping with the distress of having a loved one in prison with dementia.

Future research

This was a pilot study that produced some promising findings warranting further investigation, such as a more robust evaluation with a larger sample size, across a variety of prisons, for longer periods. Exploring the intersectionality of other protected characteristics (eg, gender and ethnicity) with age and dementia, will be particularly important to ensure the community is applicable to all.

The role of prisoner peer supporters for people with dementia in prison appeared to be key in this study, and as to date there have been no published evaluations of their work, additional study would be valuable.71 There is a particular lack of research focused on people living with dementia in prisons and on the challenges of resettlement,72 so further research on their experiences and the most effective ways to support them, would likely be useful to prison practitioners, researchers and policy-makers.

Conclusion

In the two prisons involved in this pilot study and process evaluation, DFC principles were considered applicable, and information sessions reportedly positive, but only one prison continued to work with the AS in creating and implementing DFC plans. A number of contextual factors appeared to impact both engagement with the study and also in dementia-friendly practice in prisons in general. However, perhaps the most fundamental was the balancing of resources—having to make difficult decisions about whether the numbers of both older prisoners, and prisoners with dementia, were sufficiently high to justify engagement with non-compulsory dementia-focused interventions in a context of government-sanctioned austerity and budget cuts. Without policy at government-level to focus attention on one of the most vulnerable groups living in prison, it may only be prisons with very large numbers of older prisoners that can justify interventions targeting prisoners with dementia, which raises moral, legal and ethical concerns for those who do not.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the prisoners and staff of both prisons who participated in the study, the prisoners who helped us with project design and materials, the Governors of both prisons for their permission to conduct the study and Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service, particularly Rupert Bailie, for permission and support. We would also like to thank the Alzheimer’s Society, particularly the representatives working with the prisons, and Laura Meadowcraft, Caroline Lee and Natalie Mann for contributing towards the conceptualisation of the initial proposal and its facilitation. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their time and suggestions.

Footnotes

Contributors: ST: design of study materials; facilitated focus groups and conducted interviews; led qualitative analysis, and conducted quantitative analyses; drafted the manuscript as lead author. AH: involvement with project conception and design; liaison with project partners; co-designed study materials; facilitated PPI/E, awareness sessions, interviews and focus groups; conducted qualitative analysis; contributed comments to manuscript drafts. NDW: conducted quantitative analysis and qualitative analyses; edits to manuscript drafts. TVB: Principle Investigator: conceived of and designed the study and grant proposal; oversaw and advised on all aspects of the study; design of study materials; liaison with project partners; contributed comments and edits to manuscript drafts.

Funding: This work was funded by the Department of Health and Social Care’s National Institute for Health Research, Collaboration for Leadership for Applied Health Research and Care, East of England.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care, nor of Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Advice was sought from the Anglia Ruskin University ethics committee, and full ethical approval for the study was granted by the National Offender Management Service (NOMS) – National Research Committee, with further permission obtained from the Governors of each participating prison.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Deidentified participant data are available from Orcid ID 0000-0003-0467-6393 upon request.

References

- 1. Williams BA, Stern MF, Mellow J, et al. Aging in correctional custody: setting a policy agenda for older prisoner health care. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1475–81. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ministry of Justice Prison population: 31 March 2018. London: Ministry of Justice, 2018. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/offender-management-statistics-quarterly-october-to-december-2017 [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 3. Allen G, Watson C. UK prison population statistics. House of Commons Library briefing paper. London: House of Commons Library, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ministry of Justice Prison population projections 2017 to 2022, England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice, 2017. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/639801/prison-population-projections-2017-2022.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 5. Di Lorito C, Vӧllm B, Dening T. Psychiatric disorders among older prisoners: a systematic review and comparison study against older people in the community. Aging Ment Health 2018;22:1–10. 10.1080/13607863.2017.1286453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moll A. Losing track of time: dementia and the ageing prison population. London: Mental Health Foundation, 2013. Available: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/losing-track-of-time-2013.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 7. Senior P, Forsyth K, Walsh E, et al. Health and social care services for older male adults in prison: the identification of current service provision and piloting of an assessment and care planning model. Health Services and Delivery Research. Southampton: National Institute for Health Research, 2013. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK259270/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK259270.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018]. [PubMed]

- 8. Hayes AJ, Burns A, Turnbull P, et al. Social and custodial needs of older adults in prison. Age Ageing 2013;42:589–93. 10.1093/ageing/aft066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hayes AJ, Burns A, Turnbull P, et al. The health and social needs of older male prisoners. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;27:1155–62. 10.1002/gps.3761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Combalbert N, Pennequin V, Ferrand C, et al. Cognitive impairment, self-perceived health and quality of life of older prisoners. Crim Behav Ment Health 2018;28:36–49. 10.1002/cbm.2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cipriani G, Danti S, Carlesi C, et al. Old and dangerous: prison and dementia. J Forensic Leg Med 2017;51:40–4. 10.1016/j.jflm.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee C, Haggith A, Mann N, et al. Older prisoners and the care act 2014: an examination of policy, practice and models of social care delivery. Prison Serv J 2016;224:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maschi T, Kwak J, Ko E, et al. Forget me not: dementia in prison. Gerontologist 2012;52:441–51. 10.1093/geront/gnr131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gaston S. Vulnerable prisoners: dementia and the impact on prisoners, staff and the correctional setting. Collegian 2018;25:241–6. 10.1016/j.colegn.2017.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. du Toit SHJ, McGrath M. Dementia in prisons – enabling better care practices for those ageing in correctional facilities. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 2018;81:460–2. 10.1177/0308022617744509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feczko A. Dementia in the incarcerated elderly adult: innovative solutions to promote quality care. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2014;26:640–8. 10.1002/2327-6924.12189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Justice Committee Older prisoners: fifth report of session 2013-14. London: House of Commons, 2013. Available: https://www.parliament.uk/documents/commons-committees/justice/older-prisoners.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 18. Christodoulou M. Locked up and at risk of dementia. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:750–1. 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70195-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Department of Health The future organisation of prison health care. London: Department of Health, 1999. Available: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110504020423/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4106031.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 20. Care Act UK: The Stationary Office, 2014. Available: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents/enacted [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 21. Health and Social Care Committee Prison health. London: House of Commons, 2018. Available: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmhealth/963/963.pdf [Accessed on 06 Dec 2018].

- 22. Department of Health Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia 2020. London: Department of Health, 2015. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/414344/pm-dementia2020.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 23. Department of Health Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia: Delivering major improvements in dementia care and research by 2015. London: Department of Health, 2012. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215101/dh_133176.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 24. Alzheimer’s Society Guidance for communities registering for the recognition process for dementia friendly communities. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2013. Available: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-06/DFC%20Recognition%20process%20-%20Guidance%20for%20communities_FS%20albert_4.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 25. Dean J, Silverside K, Crampton J, et al. Evaluation of the Bradford dementia friendly communities programme. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2015. Available: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/evaluation-bradford-dementia-friendly-communities-programme [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 26. Dean J, Silverside K, Crampton J, et al. Evaluation of the York dementia friendly communities programme. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2015. Available: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/evaluation-york-dementia-friendly-communities-programme [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 27. Henderson J. Dementia friendly communities: Edinburgh City initiatives 2014-2015. Edinburgh: Faith in Older People, 2015. Available: http://evaluationsupportscotland.org.uk/media/uploads/resources/dementia_friendly_edinburgh_final.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 28. Seydak E, Holmes M, Lynch S, et al. Building a dementia friendly community in Northern Ireland: learning from the DEED project in Derry. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2015. Available: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/building-dementia-friendly-community-northern-ireland-learning-deed-project-derry [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 29. Oxford Brookes University Evaluation of Hampshire dementia friendly communities: final report. Oxford: Oxford Brookes University, 2015. Available: https://ipc.brookes.ac.uk/publications/publication_814.html [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 30. Oxford Brookes University Oxford dementia challenge group: evaluation of dementia friendly communities project. Oxford: Oxford Brookes University, 2014. Available: https://ipc.brookes.ac.uk/publications/Oxfordshire_Dementia_Friendly_Communities_evaluation_-_August_2014.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 31. Innes A, Cutler C, Heward M, et al. Dorset dementia friendly communities project: final evaluation report (June 2014). Bournemouth: Bournemouth University, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stevens BA, Shaw R, Bewert P, et al. Systematic review of aged care interventions for older prisoners. Australas J Ageing 2018;37:34–42. 10.1111/ajag.12484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee C, Treacy S, Haggith A, et al. A systematic integrative review of programmes addressing the social care needs of older prisoners. Health Justice 2019;7 10.1186/s40352-019-0090-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baldwin J, Leete J. Behind bars: the challenge of an ageing prison population. Australian Journal of Dementia Care 2012;1:16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Human Rights Watch Old behind bars: the aging prison population in the United States. New York: Human Rights Watch, 2012. Available: https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/01/27/old-behind-bars/aging-prison-population-united-states [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 36. Fazel S, McMillan J, O’Donnell I. Dementia in prison: ethical and legal implications. J Med Ethics 2002;28:156–9. 10.1136/jme.28.3.156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. INVOLVE Briefing notes for researchers: involving the public in NHS, public health and social care research. Eastleigh: INVOLVE, 2012. Available: https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/9938_INVOLVE_Briefing_Notes_WEB.pdf [Accessed 18 Jun 2019].

- 38. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons HMP [Prison A (anonymised to preserve confidentiality)]. London: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons HMP [Prison B (anonymised to preserve confidentiality)]. London: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alzheimer’s Society Foundation criteria for the dementia-friendly communities recognition process. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2014. Available: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-06/DFC%20Foundation%20criteria_Fs%20Albert_4.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 41. University of Salford Dementia friendly physical environments checklist. Salford, University of Salford, 2013. Available: http://www.dementiaaction.org.uk/assets/0000/4336/dementia_friendly_environments_checklist.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 42. Corp IBM. IBM SPSS statistics for Windows. version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. QSR International Pty Ltd NVivo qualitative data analysis software. version 11. Melbourne: QSR International Pty Ltd, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Microsoft Corporation Microsoft Word. version 16.0.4390.1000. Washington: Microsoft Corporation, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Microsoft Corporation Microsoft Excel. version 16.0.4390.1000. Washington: Microsoft Corporation, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dementia Action Alliance Dementia action alliance: about, 2018. Available: https://www.dementiaaction.org.uk/who_we_are [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 48. Ministry of Justice Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) workforce quarterly: June 2017. London: Ministry of Justice, 2017. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/her-majestys-prison-and-probation-service-workforce-quarterly-june-2017 [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 49. Prison Reform Trust Prison: the facts. Bromley briefings, summer 2018. London: Prison Reform Trust, 2018. Available: http://www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/Portals/0/Documents/Bromley%20Briefings/Summer%202018%20factfile.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 50. Ministry of Justice Safety in custody quarterly bulletin: December 2017. London: Ministry of Justice, 2018. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/safety-in-custody-quarterly-update-to-december-2017 [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 51. Ministry of Justice Prison safety and reform. London: Ministry of Justice, 2016. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/565014/cm-9350-prison-safety-and-reform-_web_.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 52. Beard J, Allen G. Prison safety in England and Wales. House of Commons Library briefing paper. London: House of Commons Library, 2017. Available: https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/CBP-7467 [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 53. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons Annual report 2016-17. London: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons, 2017. Available: http://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2017/07/HMIP-AR_2016-17_CONTENT_11-07-17-WEB.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 54. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons ‘No problems – old and quiet’: Older prisoners in England and Wales. London: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons, 2004. Available: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2014/08/OlderPrisoners-2004.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 55. Brunton-Smith I, Hopkins K. The factors associated with proven re-offending following release from prison: findings from waves 1 to 3 of SPCR – results from the surveying prisoner crime reduction (SPCR) longitudinal cohort study of prisoners. Ministry of Justice analytical series. London: Ministry of Justice, 2013. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/491119/re-offending-release-waves-1-3-spcr-findings.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 56. Omolade S. The needs and characteristics of older prisoners: results from the surveying prisoner crime reduction (SPCR) survey. Ministry of Justice analytical summary. London: Ministry of Justice, 2014. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/368177/needs-older-prisoners-spcr-survey.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 57. Ministry of Justice Proven reoffending tables (3 monthly), April 2016 to June 2016. London: Ministry of Justice, 2018. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/proven-reoffending-statistics-april-2016-to-june-2016 [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 58. House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts Mental health in prisons: eighth report of session 2017-19. London: House of Commons, 2017. Available: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmpubacc/400/400.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 59. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons. Annual report 2015-16, 2016. Available: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/07/HMIP-AR_2015-16_web.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 60. Prisons & Probation Ombudsman Learning lessons bulletin: Dementia, 2016. Available: http://www.ppo.gov.uk/app/uploads/2016/07/PPO-Learning-Lessons-Bulletins_fatal-incident-investigations_issue-11_Dementia_WEB_Final.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 61. Prisons & Probation Ombudsman Learning from PPO investigations: older prisoners, 2017. Available: http://www.ppo.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/6-3460_PPO_Older-Prisoners_WEB.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 62. Cornish N, Edgar K, Hewson A, et al. Social care or systemic neglect? older people on release from prison. London: Prison Reform Trust, 2016. Available: http://www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/Portals/0/Documents/Older-prisoner-resettlement.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 63. Ministry of Justice Government response to the Justice Committee’s fifth report of session 2013-14: ‘Older Prisoners’. London: Ministry of Justice, 2014. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/256609/response-older-prisoners.pdf [Accessed 06 December 2018].

- 64. Wangmo T, Handtke V, Bretschneider W, et al. Prisons should mirror Society: the debate on age-segregated housing for older prisoners. Ageing Soc 2017;37:675–94. 10.1017/S0144686X15001373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kerbs JJ, Jolley JM, Kanaboshi N. The interplay between law and social science in the age-segregation debate. J Crime Justice 2015;38:77–95. 10.1080/0735648X.2014.894856 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Alzheimer’s Society Making Your Home Dementia Friendly. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2015. Available: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-support/making-your-home-dementia-friendly [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 67. The King’s Fund Developing supportive design for people with dementia: The King’s Fund Enhancing the Healing Environment Programme 2009-2012. London: The King’s Fund, 2013. Available: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/developing-supportive-design-people-dementia [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 68. The King’s Fund Environments for care at end of life: The King’s Fund Enhancing the Healing Environment Programme 2008-2010. London: The King’s Fund, 2011. Available: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/environments-care-end-life [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 69. The Howard League for Penal Reform Preventing prison suicides: perspectives from the inside. London: The Howard League for Penal Reform, 2016. Available: https://howardleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Preventing-prison-suicide.pdf [Accessed 06 Dec 2018].

- 70. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2018. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97/chapter/Recommendations#supporting-carers [Accessed 06 Dec 2018]. [PubMed]

- 71. Stewart W, Edmond N. Prisoner peer caregiving: a literature review. Nursing Standard 2017;31:44–51. 10.7748/ns.2017.e10468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Dillon G, Vinter LP, Winder B, et al. ‘The guy might not even be able to remember why he’s here and what he’s in for and why he’s locked in’: residents and staff experiences of living and working alongside people with dementia who are serving prison sentences for a sexual offence. Psychol Crime Law 2018:1–18. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030087supp001.pdf (80.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030087supp002.pdf (68.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030087supp003.pdf (117KB, pdf)