Abstract

Introduction

In-vivo fluorescence imaging techniques using indocyanine green (ICG) to identify liver tumours and hepatic segment boundaries have been recently developed. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of fusion ICG-fluorescence imaging for navigation during hepatectomy.

Methods and analysis

This will be an exploratory single-arm clinical trial; patients with liver tumours will undergo hepatectomy using the ICG-fluorescence imaging system. In total, 110 patients with liver tumours scheduled for elective hepatectomy will be included in this study. Preoperatively, ICG will be intravenously injected at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg body weight within 2 days. To detect liver tumours intraoperatively, the hepatic surface will be initially observed using the ICG-fluorescence imaging system. After identifying and clamping the portal pedicle corresponding to the hepatic segments, including the liver tumours to be resected, additional ICG will be injected intravenously at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg body weight to identify the boundaries of the hepatic segments. The primary outcome measure will be the success or failure of the ICG-fluorescence imaging system in identifying hepatic segments. The secondary outcomes will be the success or failure in identifying liver tumours, liver function indicators, operative time, blood loss, rate of postoperative complications and recurrence-free survival. The findings obtained through this study are expected to help to establish the utility of ICG-fluorescence imaging systems, and therefore contribute to prognostic outcome improvements in patients undergoing hepatectomy for various causes.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol has been approved by the Kobe University Clinical Research Ethical Committee. The findings of this study will be disseminated widely through peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations.

Trial registration number

UMIN000031054 and jRCT1051180070

Keywords: indocyanine green-fluorescence imaging, liver tumour, hepatectomy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is expected to address the clinical utility of real-time navigation during hepatectomy using indocyanine green (ICG)-fluorescence imaging systems.

The efficacy and safety of hepatectomy using ICG-fluorescence imaging systems are expected to be clarified through the analysis of associations between the success rate in identifying hepatic segments and clinical outcomes, including liver function indicators, operative time, blood loss, rate of postoperative complications and recurrence-free survival.

This is an exploratory single-arm study, the results of which will be compared against historical data from our facility.

Introduction

Hepatectomy remains the mainstay of treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and metastatic liver tumours and is commonly performed in patients with preserved liver function.1–3 Vascular invasion is a poor prognostic factor in HCC, and anatomical resection of the cancer-bearing portal regions is a theoretically effective procedure for the treatment of HCC and metastatic liver tumours complicated by invasion of the Glisson’s capsule.4

To perform anatomical resection safely and precisely, the liver’s anatomical boundaries must be visually recognised. Particularly, the hepatic veins are considered to indicate the absolute boundaries of hepatic segments and can easily be identified by intraoperative ultrasonography. However, due to the three-dimensional shape of the hepatic segment, the hepatic veins are not sufficient for guiding anatomical resection. Under such conditions, intraoperative navigation in hepatectomy allows for the real-time identification of three-dimensional structures, including tumours and hepatic segment boundaries.

Several techniques for identifying hepatic segments have been reported thus far.5–9 Recently, in-vivo fluorescence imaging techniques for the identification of biological structures intraoperatively have been developed. Among the various fluorophores used, indocyanine green (ICG) receives a substantial amount of attention because of its well-known pharmacokinetic and safety profile, making it a potentially valuable clinical tool.10 For example, it is well known that ICG rapidly and completely binds to plasma proteins—among which albumin is the principal carrier—following intravenous injection. Also, ICG is excreted in bile in an unconjugated form and is not cleared by extrahepatic mechanisms. Furthermore, single or repeated intravenous injections or infusions rarely cause unfavourable adverse effects. Taking advantage of these characteristics and the development of concomitant fluorescence imaging techniques, ICG-fluorescence imaging systems are widely used for detecting sentinel lymph nodes and arterial blood flow, and their effectiveness has been recognised.11 12 Moreover, the potential utility of this approach to identify liver tumours and hepatic segment boundaries, as well as to detect the bile duct tree intraoperatively, has recently been demonstrated.7 13–19

The ICG-fluorescence imaging system was initially introduced for use during open hepatectomy. Similar fluorescence imaging systems have been recently developed for use during laparoscopic hepatobiliary surgery. Several reports have demonstrated the efficacy of such systems during laparoscopic cholecystectomy and hepatectomy.20 However, whether the hepatic boundaries visualised by ICG-fluorescence imaging systems are clinically precise and useful has not been adequately assessed. For example, there may be minor deviations due to the confluence of communicating vessel branches between hepatic segments; the injected ICG likely passes through the hepatic segments and the tumour to be removed. Evidence regarding the efficacy of ICG-fluorescence imaging systems is not fully established, and further investigation is required.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of the ICG-fluorescence imaging system during hepatectomy for patients with liver tumours by analysing the rate of detection of hepatic boundaries and tumours. In addition, we assess the precision of the detected hepatic boundaries by evaluating the postoperative clinical data.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This prospective study is a single-arm, exploratory clinical trial. Patients with liver tumours will undergo hepatectomy using the ICG-fluorescence imaging system. This study will be performed at Kobe University.

Target population

From 2018 to 2020, patients with liver tumours treated at Kobe University will be enrolled. The inclusion criteria are as follows: male or female patients with liver tumours, aged 20 years and older, scheduled for elective hepatectomy, have preserved liver function, able to understand the nature of the study procedures, and willing to participate and give voluntary written consent. Liver functional reserve will be assessed by serum biochemical data (albumin level, total bilirubin level and prothrombin time) and ICG retention for 15 min (ICG-R15). The patients will be categorised according to the severity of liver disease based on Child-Pugh stages and the liver damage classification, defined by the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan.21 22 Preserved liver function is defined as ICG-R15<15% and a Child-Pugh classification of A or B.

The exclusion criteria are as follows: has liver or renal insufficiency, or known ICG hypersensitivity, pregnant or breastfeeding, or unable to understand the nature of the study procedure.

Intervention

ICG is injected intravenously at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg body weight within 2 days preoperatively. Intraoperatively, we will initially observe the hepatic surface using a fusion ICG-fluorescence imaging system (PINPOINT; Stryker, Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA) to detect liver tumours. Among several methods for identifying liver segments with fluorescence imaging, we will use the negative staining technique to identify the liver segments in this study.23 After identifying and clamping the portal pedicle corresponding to the hepatic segments to be removed, additional ICG is injected intravenously at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg body weight to identify the boundaries of the hepatic segments.24 Hepatectomy is performed based on the demarcation between fluorescing and non-fluorescing areas, which are assumed to be the boundaries of the hepatic segments. The demarcation will also be checked as continuously as possible during parenchymal resection. Parenchymal resection will be performed using an ultrasonic surgical aspirator (CUSA; Cavitron Lasersonic Corp., Stamford, Connecticut, USA) and a bipolar clamp coagulation system (ERBE, Tubingen, Germany). The fusion ICG-fluorescence images will only be used for the hepatectomy. The Pringle manoeuvre will be performed and a drainage tube will be routinely inserted around the cut surface of the liver parenchyma.

Sample size calculation

The purpose of the primary analysis of this study is to estimate the success rate, which is defined as the proportion of hepatic segments identified by the ICG-fluorescence imaging system during hepatectomy. In order to judge the procedure as useful, a success rate of at least 80% is thought to be required. When the expected success rate is 90% and the two-sided 95% CI width is 0.12, the required number of participants is 98. To allow for an approximately 10% dropout, the target sample size of this study has been set to 110.

Outcome measures

Primary endpoint

The primary endpoint is the success and failure of identifying hepatic segments using the ICG-fluorescence imaging system. We will evaluate the identification of hepatic segments at two points: observation of the liver surface and the hepatic transection surface. We assume that identification is successful when fulfilling the following two criteria:

Hepatic surface

Identification of hepatic segments by the ICG-fluorescence imaging system is considered successful when the demarcation between fluorescing and non-fluorescing areas is consistent with the ischaemic demarcation area observed by clamping the portal pedicle.

Hepatic transection surface

Hepatic parenchymal resection is performed based on the demarcation between fluorescing and non-fluorescing areas, which are assumed to be the boundaries of the hepatic segments. We divide the time taken to perform parenchymal resection into three equal intervals by reviewing the recorded videos after surgery, and the identification of hepatic segment boundaries is evaluated at each interval. Identification of hepatic segments is considered successful when we can identify the hepatic segments in more than 80% of the transected area during parenchymal resection at more than two intervals.

Secondary endpoints

The secondary endpoints are the success and failure of identifying liver tumours by the ICG-fluorescence imaging system, liver function indicators (alanine transaminase, albumin, total bilirubin, international normalised ratio of prothrombin time and platelet count), the operative time, the blood loss, the rate of postoperative complications and recurrence-free survival. Successful identification of liver tumours is determined when any isolated fluorescence signals are detected, also considering liver tumours diagnosed by other modalities, including preoperative imaging and intraoperative ultrasonography, and finally confirmed by pathological examination. The fluorescence pattern is considered according to the preoperative diagnosis because liver lesions have differing fluorescence patterns based on their tumour biology.25 If we identify lesions with isolated fluorescence signal on fusion-fluorescence imaging that were not identified by preoperative imaging, we evaluate the lesions by intraoperative ultrasound sonography, and, if necessary, frozen section biopsies are performed to determine whether additional hepatectomy is required. The recurrence-free survival is analysed for each case of liver tumour, including primary liver cancer and liver metastases. Recurrence-free survival time is defined as the time from enrolment until the first recurrence after the surgical intervention. Patients without recurrence will be censored at the date of last confirmation of recurrence-free status. Patients lost to follow-up without a diagnosis of recurrence and those who die will be censored at the date of last confirmation of recurrence-free status.

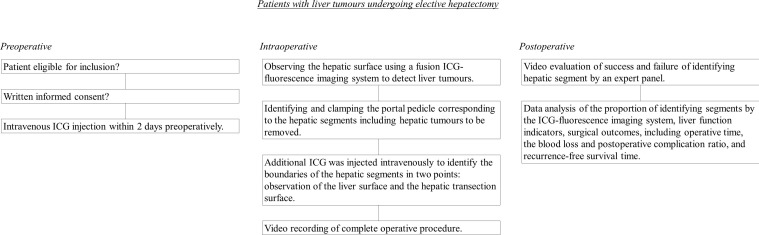

Data collection

Three experienced surgeons will judge the intraoperative identification of hepatic segment boundaries. The entire surgical procedure, including ICG-fluorescence imaging, will be digitally recorded and analysed by an additional expert panel consisting of three highly experienced surgeons, different from those performing the surgeries, to confirm the identification of hepatic segment boundaries. When we perform an open hepatectomy, the video will be captured by another surgeon using the scope of a fusion ICG-fluorescence imaging system. When we perform a laparoscopic hepatectomy, the ICG-fluorescence images can be accessed through the laparoscope. The success rate of their identification is used as the endpoint. A flow chart of the study procedure is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study procedures. ICG, indocyanine green.

Postoperative complications will be graded according to the extended Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications, which was published by the Japan Clinical Oncology Group and more precisely described in the original criteria of the Clavien-Dindo classification.26 27

Follow-up visits will be carried out at 2 weeks after hospital discharge, and every 3 months thereafter. Follow-up evaluation will be performed using routine blood tests, including liver function tests, coagulation function tests, serum tumour marker levels depending on the type of liver tumour, abdominal ultrasonography and abdominal enhanced CT.

Study timeline

Data will be collected from February 2018 to January 2020, and analysis is estimated to be completed by January 2022.

Participants will be informed about the study during their preoperative visit to our hospital, and will have ample time to consider participation. Possible complications will be evaluated in the year following the surgery. The schedules of enrolment, interventions and assessments are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments

| Study period | ||||||

| Within 14 days before registration | Before surgery | Day of surgery | After surgery | Day of discharge | Every 3 months after discharge | |

| Enrolment | ||||||

| Eligibility screen | X | |||||

| Informed consent | X | |||||

| Background Blood test |

X | |||||

| Interventions | ||||||

| ICG-fluorescence imaging technique | X | |||||

| Assessments | ||||||

| Primary outcome | X | X | ||||

| Blood test | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Postoperative complication | X | X | X | |||

| Adverse event | X | X | X | |||

| Abdominal ultrasonography | X | |||||

| Abdominal enhanced CT | X | |||||

ICG, indocyanine green.

Statistical analysis

The analysis populations will include the following three sets. First, the full analysis set (FAS) will consist of all participants who completed the surgery with navigation by ICG-fluorescence images and have efficacy data available, excluding those who have missing baseline data or have had significant protocol violations (eg, absence of informed consent and enrolment outside the contract period). Second, the per protocol set (PPS) will consist of the FAS participants completing 1 year of follow-up, excluding those with any significant protocol violations involving the study method, the inclusion criteria, the exclusion criteria and concomitant therapy. Lastly, the safety analysis set (SAS) will consist of the participants who enrolled in this study and were given at least one dose of ICG.

The analysis will be performed after the data lock following completion of study drug administration to all participants. For all efficacy endpoints, the FAS will be used in the primary analysis, while the PPS will be used in a reference analysis. Safety will be analysed using the SAS. The baseline distribution of participant characteristics and summary statistics will be calculated according to the group in each analysis population.

All statistical analyses will be performed as indicated using JMP software, V.13.0.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Interim analyses will not be performed in this study.

Primary outcome

The primary objective of this study is to estimate the success rate, which is defined as the proportion of hepatic segments identified by the ICG-fluorescence imaging system. The point estimate of the rate and the 95% CI will be calculated.

Secondary outcomes

The point estimate and 95% CI of the success rate of tumour detection by the ICG- fluorescence imaging system will be calculated. For analysis of other secondary outcomes, we will conduct a test using historical data collected at our facility as the control group. No multiplicity adjustment will be performed in the analysis of secondary efficacy endpoints. We will estimate the recurrence-free survival by the Kaplan-Meier method. The recurrence-free survival will also be analysed by univariate Cox proportional hazard model for each clinical variable. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard models will be adopted to analyse the risk factors of recurrence-free survival. The following variables will be included in the multivariate model: the success or failure of identifying liver segments using the ICG-fluorescence imaging system and other variables for which the p value is under 0.05 in the univariate analysis.

Safety analysis

The safety endpoint of this study is the frequency of adverse events. A table will be prepared to summarise the endpoint. For estimation of the rates of adverse events, a two-sided 95% CI will be calculated.

Data monitoring

Monitoring will be performed to periodically check whether the study is being conducted safely in accordance with the protocol and whether the data are properly collected. The following items are reviewed every 6 months: informed consent, obtained and signed; participant retention; study implementation system; study safety and data; and study progress.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient and/or public involvement in the planning of this study.

Ethics and dissemination

Is there scientific and clinical value in conducting this study?

Whereas the conventional pedicle clamping method can only detect hepatic boundaries from the hepatic surface, the ICG-fluorescence imaging system can detect both the hepatic and transection surfaces during parenchymal resection. We can evaluate the efficacy and safety of hepatectomy using ICG-fluorescence imaging systems by analysing the association between the success rate of identifying hepatic segments and clinical outcomes. This study will help to determine whether the boundaries detected by ICG-fluorescence imaging systems during hepatectomy are valid and useful.

The findings obtained through this study will help to establish the utility of ICG-fluorescence imaging systems and therefore, the study is expected to contribute to the improvement of prognostic outcomes in patients who undergo hepatectomy due to various causes.

Ethical approval

Possible protocol amendments will be sent to the Kobe University Clinical Research Ethical Committee.

Consideration of participants’ human rights, safety and disadvantages

The principal investigator and sub-investigators will comply with the principals of the protection of participants’ privacy rights. Study personnel will make the utmost effort to protect the participants’ personal information and privacy, and will not divulge any personal information learnt from this study without due reasons, even outside working hours. In this study, a list of subject identification codes will be prepared to link the subject source data with the study database or study-related documents. Limited participant information, such as sex and date of birth, may be used to identify participants or verify the list of subject identification codes, within the range of all applicable laws and regulations.

All effort will be taken to ensure that participants will not be personally identifiable from publications arising from this study.

Foreseeable disadvantages (burdens and risks)

The administration of ICG will be the only additional invasive intervention performed in each patient. ICG administration rarely causes anaphylactic reactions (<1:10 000). Patients with terminal renal insufficiency seem to be more prone to such an anaphylactic reaction. The estimated mortality rate due to anaphylactic reaction is reported as <1 per 330 000.28–31

To minimise the risk of adverse events and disadvantages that may occur in this study, the inclusion and exclusion criteria have been carefully discussed. All adverse events occurring in this study will be monitored to ensure that they are within the expected range. If any serious or unexpected adverse events occur, the event will be carefully examined and reviewed, and the necessary countermeasures will be taken. Participation in this study may require increased hospital visits, test frequency and blood sampling volume, compared with routine medical care. In the event of tumour progression, severe organ dysfunction, physical weakening, and so on, during the preoperative treatment or the waiting period for surgical resection, the planned surgical resection may not be possible.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

HG and SK contributed equally.

Contributors: HG, SK, SM, MK, MT, KK, DT, MA, HT and TF all made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. HG, SK and SM drafted the manuscript. All the authors provided critical review and final approval of the present manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Written informed consent was provided by all patients.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Kobe University Clinical Research Ethical Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Fong ZV, Tanabe KK. The clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States, Europe, and Asia: a comprehensive and evidence-based comparison and review. Cancer 2014;120:2824–38. 10.1002/cncr.28730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3677–83. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y, et al. Japanese Society for cancer of the colon and rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2014 for treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2015;20:207–39. 10.1007/s10147-015-0801-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hasegawa K, Kokudo N, Imamura H, et al. Prognostic impact of anatomic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 2005;242:252–9. 10.1097/01.sla.0000171307.37401.db [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Makuuchi M, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki S. Ultrasonically guided subsegmentectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1985;161:346–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Takasaki K. Glissonean pedicle transection method for hepatic resection: a new concept of liver segmentation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 1998;5:286–91. 10.1007/s005340050047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aoki T, Yasuda D, Shimizu Y, et al. Image-Guided liver mapping using fluorescence navigation system with indocyanine green for anatomical hepatic resection. World J Surg 2008;32:1763–7. 10.1007/s00268-008-9620-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ahn KS, Kang KJ, Park TJ, et al. Benefit of systematic segmentectomy of the hepatocellular carcinoma: revisiting the dye injection method for various portal vein branches. Ann Surg 2013;258:1014–21. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318281eda3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hallet J, Gayet B, Tsung A, et al. Systematic review of the use of pre-operative simulation and navigation for hepatectomy: current status and future perspectives. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2015;22:353–62. 10.1002/jhbp.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cherrick GR, Stein SW, Leevy CM, et al. Indocyanine green: observations on its physical properties, plasma decay, and hepatic extraction. J Clin Invest 1960;39:592–600. 10.1172/JCI104072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kitai T, Inomoto T, Miwa M, et al. Fluorescence navigation with indocyanine green for detecting sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer. Breast Cancer 2005;12:211–5. 10.2325/jbcs.12.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reuthebuch O, Häussler A, Genoni M, et al. Novadaq Spy: intraoperative quality assessment in off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Chest 2004;125:418–24. 10.1378/chest.125.2.418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ishizawa T, Fukushima N, Shibahara J, et al. Real-Time identification of liver cancers by using indocyanine green fluorescent imaging. Cancer 2009;115:2491–504. 10.1002/cncr.24291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gotoh K, Yamada T, Ishikawa O, et al. A novel image-guided surgery of hepatocellular carcinoma by indocyanine green fluorescence imaging navigation. J Surg Oncol 2009;100:75–9. 10.1002/jso.21272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ishizawa T, Bandai Y, Ijichi M, et al. Fluorescent cholangiography illuminating the biliary tree during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 2010;97:1369–77. 10.1002/bjs.7125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaibori M, Ishizaki M, Matsui K, et al. Intraoperative indocyanine green fluorescent imaging for prevention of bile leakage after hepatic resection. Surgery 2011;150:91–8. 10.1016/j.surg.2011.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van der Vorst JR, Schaafsma BE, Hutteman M, et al. Near-Infrared fluorescence-guided resection of colorectal liver metastases. Cancer 2013;119:3411–8. 10.1002/cncr.28203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Inoue Y, Arita J, Sakamoto T, et al. Anatomical liver resections guided by 3-dimensional parenchymal staining using fusion indocyanine green fluorescence imaging. Ann Surg 2015;262:105–11. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miyata A, Ishizawa T, Tani K, et al. Reappraisal of a Dye-Staining technique for anatomic hepatectomy by the concomitant use of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging. J Am Coll Surg 2015;221:e27–36. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Spinoglio G, Priora F, Bianchi PP, et al. Real-Time near-infrared (NIR) fluorescent cholangiography in single-site robotic cholecystectomy (SSRC): a single-institutional prospective study. Surg Endosc 2013;27:2156–62. 10.1007/s00464-012-2733-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, et al. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices.. Br J Surg 1973;60:646–9. 10.1002/bjs.1800600817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The liver Cancer Study Group of Japan The general rules of the clinical and pathological study of primary liver cancer. 3th edn Tokyo: Kanehara, 2010: 1–110. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kobayashi Y, Kawaguchi Y, Kobayashi K, et al. Portal vein Territory identification using indocyanine green fluorescence imaging: technical details and short-term outcomes. J Surg Oncol 2017;116:921–31. 10.1002/jso.24752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Uchiyama K, Ueno M, Ozawa S, et al. Combined intraoperative use of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography imaging using a sonazoid and fluorescence navigation system with indocyanine green during anatomical hepatectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2011;396:1101–7. 10.1007/s00423-011-0778-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abo T, Nanashima A, Tobinaga S, et al. Usefulness of intraoperative diagnosis of hepatic tumors located at the liver surface and hepatic segmental visualization using indocyanine green-photodynamic eye imaging. Eur J Surg Oncol 2015;41:257–64. 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P-A. Classification of surgical complications. Ann Surg 2004;240:205–13. 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Katayama H, Kurokawa Y, Nakamura K, et al. Extended Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: Japan clinical Oncology Group postoperative complications criteria. Surg Today 2016;46:668–85. 10.1007/s00595-015-1236-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Benya R, Quintana J, Brundage B. Adverse reactions to indocyanine green: a case report and a review of the literature. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1989;17:231–3. 10.1002/ccd.1810170410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wolf S, Arend O, Schulte K, et al. Severe anaphylactic reaction after indocyanine green fluorescence angiography. Am J Ophthalmol 1992;114:638–9. 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)74501-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hope-Ross M, Yannuzzi LA, Gragoudas ES, et al. Adverse reactions due to indocyanine green. Ophthalmology 1994;101:529–33. 10.1016/S0161-6420(94)31303-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van den Bos J, Schols RM, Luyer MD, et al. Near-Infrared fluorescence cholangiography assisted laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy (falcon trial): study protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011668 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.