Abstract

Objective

Evidence-based clinical resources (EBCRs) have the potential to improve diagnostic and therapeutic accuracy. The majority of US teaching medical institutions have incorporated them into clinical training. Many EBCRs are subscription based, and their cost is prohibitive for most clinicians and trainees in low-income and middle-income countries. We sought to determine the utility of EBCRs in an East African medical school.

Setting

The University of Rwanda (UR), a medical school located in East Africa.

Participants

Medical students and faculty members at UR.

Interventions

We offered medical students and faculty at UR free access to UpToDate, a leading EBCR and conducted a cohort study to assess its uptake and usage. Students completed two surveys on their study habits and gave us permission to access their activity on UpToDate and their grades.

Results

Of the 980 medical students invited to enrol over 2 years, 547 did (56%). Of eligible final year students, 88% enrolled. At baseline, 92% of students reported ownership of an internet-capable device, and the majority indicated using free online resources frequently for medical education. Enrolled final year students viewed, on average, 1.24 topics per day and continued to use UpToDate frequently after graduation from medical school. Graduating class exam performance was better after introduction of UpToDate than in previous years.

Conclusions

Removal of the cost barrier was sufficient to generate high uptake of a leading EBCR by senior medical students and habituate them to continued usage after graduation.

Keywords: information technology; general medicine (see internal medicine); EBCR, global medical education; global health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first reported longitudinal prospective cohort study of health professionals and trainees in Africa.

This is the first study to link usage of online educational resources to performance in medical school examinations in Africa.

Our ability to precisely track online usage of UpToDate eliminates recall bias that is likely to significantly impact findings of studies of educational interventions that are based on self-reporting.

Given the observational nature of our study, we cannot make causal claims on the relationship between student use of UpToDate and their performance on medical school examinations.

The relatively short follow-up period discussed in this paper limits our ability to understand the long-term impact of offering UpToDate access to African health trainees.

Introduction

The velocity of growth of the clinical evidence base is staggering: In the last 3 years alone, over 16 000 unique clinical studies posted new results on ClinicalTrials.gov.1 There is more information emerging every year than any one person could ever retain. In response, educators in the US have called for a shift in the basic paradigm of medical education, de-emphasising the passive presentation of material and promoting problem-solving skills and the ability to find information and adapt it to the clinical situation at hand.2 The Liaison Committee on Medical Education mandates that self-directed learning be part of every accredited school’s curriculum, and the American Board of Internal Medicine recently announced that maintenance of certification exams for internists and nephrologists will be open-book.3 4 The historical focus on memorisation is giving way to an emphasis on knowing how to find information, synthesise it and apply it clinically. Clinicians who have not developed these skills during medical school or clinical training are at a disadvantage, which, ultimately, means their patients are at a disadvantage.5-7

The ability to access and synthesise clinical information effectively and efficiently is particularly crucial for clinicians in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). The health workforce shortage and absence of specialists forces clinicians to care for more patients with a broader range of complaints than their counterparts in high-income countries. Rwanda, a country of 11 million people, had, until recently, a total of 15 anaesthesiologists, 25 obstetricians and zero neurologists.8 9 In addition, a study of 21 hospitals in LMICs documented substantial knowledge gaps among physicians.10 Constraints in medical education in these countries are likely responsible for both workforce and knowledge gaps. In 2011, the Sub-Saharan African Medical School Study group surveyed 146 of 168 medical schools in the region and found widespread shortages in qualified faculty and infrastructure.11

To address the challenge of the rapidly expanding evidence base in medicine, several organisations in high-income countries have created evidence-based clinical resources (EBCRs), regularly updated, expert-authored, online tools that synthesise the primary literature to guide clinical decision making. Over the years, UpToDate, which was founded at Harvard Medical School in 1992, has emerged as a leading EBCR in high-income countries, and several studies have documented its utility: Use of UpToDate has been associated with improved examination performance among internal medicine residents, as well as lower mortality at US hospitals.5 6 As of February 2018, 90% of teaching US medical institutions and 100% of the top 20 US medical schools (as ranked by US News & World Report) subscribed to UpToDate.12-14 Despite the high demand for UpToDate in US medical education, none of the 168 medical schools in Sub-Saharan Africa subscribe to its services, partly because of the high subscription cost. An individual physician subscription to UpToDate in Rwanda costs $299 per year; Rwanda spent $52 per capita on healthcare in 2014.15 Additionally, cost of internet access can be prohibitively high in some LMICs; at the time of publication, mobile internet in Rwanda cost approximately $0.05 per megabyte.16

Given their utility in high-income countries, access to EBCRs could help address some of the challenges faced by clinicians in LMICs. We believe that access to better evidence could improve the knowledge base of these clinicians, increase their perception of self-efficacy and create a professional habit of seeking evidence at the point of care. This could be particularly beneficial for clinicians caring for a large number of complex patients without access to specialists. We have previously reported on a programme, which provides donated UpToDate subscriptions to clinicians in LMICs, in which we found that most use UpToDate with high frequency, and many report changing their clinical decision making as a result of having access to UpToDate.17

While EBCRs have traditionally been developed for physicians in practice, there are reasons to believe that their introduction to medical students would be beneficial. First, medical school is de facto the first locus of professional habit formation, and often their last formal one, as many clinicians in LMICs do not receive postgraduate education. Additionally, providing access to EBCRs to medical students in LMICs is a matter of equity: students who have worked hard to care for their community in LMICs should have the same opportunity to learn and provide quality care as their counterparts in US medical schools. In this article, we hypothesised that removing the subscription cost barrier to accessing EBCR will lead to high student uptake and possibly lead to an improvement in educational outcomes.

Methods

Setting

The University of Rwanda (UR) was the only medical degree–granting school in Rwanda at the time this study launched and is a public university. Seventy-six percent of students at UR are recipients of bursaries from the Government of Rwanda.18 Medical students enter UR after successful completion of high school and, during the study period, completed a 6-year medical education curriculum consisting of 2 years of preclinical education followed by 4 years of clinical education in the wards.

Intervention

In the fall of 2014, the authors formed an agreement with Wolters Kluwer, the parent company of UpToDate, to facilitate the donations of UpToDate subscriptions to medical students in Sub-Saharan Africa. With appropriate institutional review board approval, medical students and faculty at the University of Rwanda were invited by email to enrol in our study. ‘Faculty member’ was defined as anyone who teaches undergraduate medical students, which meant that residents, as well as staff physicians, were considered faculty. Undergraduate medical students, who unlike US medical students are admitted to medical school after high school at age 18 years, were invited to enrol as well. Students were invited in cohorts that spanned the different years of medical school (see online supplementary table 1). Enrolment was voluntary and not mandated by faculty or the curriculum. Each participant received a free 5-year individual subscription to UpToDate, which allowed them to access the website from any computer or mobile device. The authors undertook no recruitment or training efforts. Data reported in this paper was generated in 2015–2017. All study subjects will be eligible for getting free UpToDate access after the 5 years of the study through a donation programme that UpToDate has created for all medical doctors practising in resource-limited settings. This donation programme is available to any medical provider in a low-income and middle-income country and gives free, unlimited access to UpToDate without a time limit. Donations have to be renewed annually. Hence, all study subjects will be able to get free UpToDate access after this study concludes, for as long as they practice medicine in a resource-limited setting. The donation programme details can be found here: https://www.ariadnelabs.org/better-evidence/.

bmjopen-2018-026947supp001.pdf (66.7KB, pdf)

Evaluation

Students were asked to complete an online baseline survey to document their study habits before provision of UpToDate and an Annual Evaluation survey. We chose questions around students’ baseline utilisation of the internet in medical education, as others have identified access to devices and the internet as potential barriers to EBCR utilisation.19 Students’ responses over time were linked using their name and email. All participant activity on the UpToDate website and mobile application was tracked remotely and linked to survey responses. An anonymised dataset of all student grades for the graduating classes of 2012–2017 was obtained to assess the impact of UpToDate on class examination performance. Lastly, to understand student usage of UpToDate over time, we plotted the average number of topics viewed per month by active users. To characterise a stable cohort of users over time, we plotted the average number of topics viewed by students in their final year who enrolled before 1 March 2016.

Data analysis

To understand EBCR usage patterns by students and faculty, we calculated for each user the number of topics viewed. Any action resulting in the opening of a new UpToDate card (with a distinct title) was counted as a new topic. Viewing of the same topic in the same session was counted only once. A session was defined as the period using UpToDate, initiated by a unique log-on of a user to the UpToDate website, mobile site or mobile application and terminated when the user logged off, closed the application or remained inactive for more than 3 hours. To calculate the average daily usage (ADU), the number of topics viewed was divided by the number of days that the user had an active account. The number of days with an active account was defined as the interval between the user’s first-ever log-on and the end of the study period (31 October 2017). To identify predictors of high usage frequency, we conducted a multivariable linear regression after applying the natural log transform to ADU values to approximate normality.

To understand the impact of UpToDate on the overall exam performance of the graduating class at UR, we calculated the average grade of each graduating student for 2012–2017 by averaging his or her performance on graduation exams. Exams were written and clinical in the following subjects: internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology and paediatrics. To assess the impact of UpToDate, we performed two tests: first, we performed a two-sided heteroscedastic t-test between grades assigned before UpToDate provision (2012–2015) and grades assigned after (2016–2017). To control for variability due to the year of exam administration, we performed a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with year of exam and UpToDate provision as the independent variables and average exam grade as the dependent variable.

Data analysis was performed on Stata SE 14 and Microsoft Excel.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not the subject of this study. Given the setting of the study at a medical school, it was not feasible to include a patient partner. A medical student at UR (BN) is a co-author of this study and brought the student perspective into the interpretation of the data.

Results

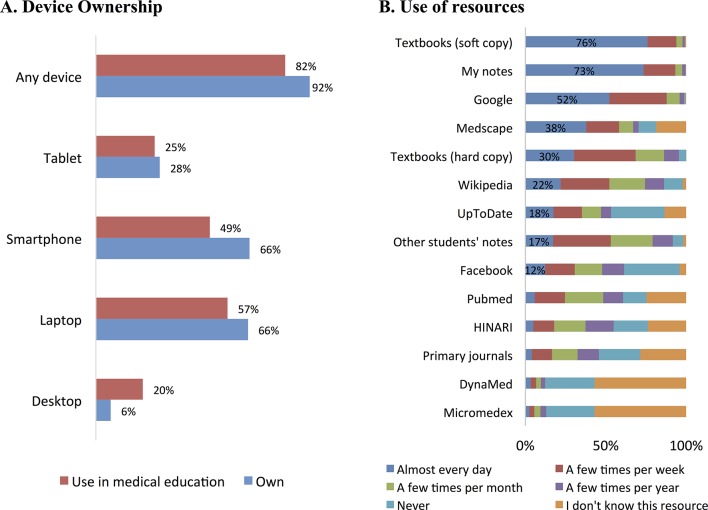

Of the 980 students and 1084 faculty invited to enrol into the study during the 2015–2017 study period, 547 (56%) students and 325 (29%) faculty did. The highest enrolment rate (87%) was observed among students in their final (sixth) year of medical school, who are called ‘Doctorate 4’ or Doc4 students at UR (online supplementary table 1). In our baseline survey, 92% of student respondents overall and 96% of Doc4 students reported ownership of at least one internet-capable device (figure 1A). Free electronic resources—primarily Medscape, Google and Wikipedia—were used frequently for the purposes of medical education (figure 1B). A small percentage reported frequent usage of UpToDate at baseline.

Figure 1.

Baseline survey of Rwandan medical students. (A) The percentage of students at UR reporting that they own a particular internet capable device or use it in medical education. ‘Any device’ refers to any of the following: tablet, smartphone, laptop and desktop. (B) The percentage of students indicating that they use a specific resource to study for coursework or prepare for examinations. n=547 UR students UR, University of Rwanda.

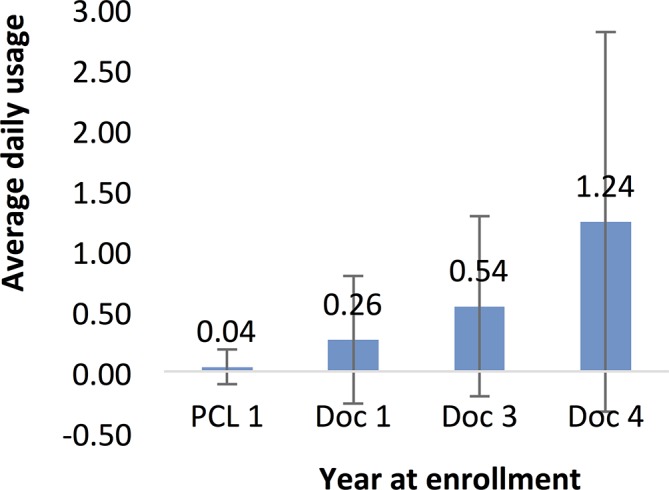

All users who completed the enrolment survey had an individual UpToDate account created for them and received an email with instructions on how to set up their UpToDate password. Of those who activated their UpToDate account, 76% of faculty and 64% of students viewed, on average, at least one UpToDate topic per week; 13% of faculty and 23% of students viewed, on average, one topic or more per day. In a multivariate linear regression looking at variables associated with UpToDate usage frequency, student year at enrolment was the only significantly associated variable (table 1). Figure 2 shows average UpToDate usage by year of student at enrolment.

Table 1.

Multivariate linear regression with UpToDate usage as the dependent variable

| Variable | Coefficients | P value |

| Cohort | −0.04 | 0.21 |

| Year at enrolment | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Own any device | 0.07 | 0.29 |

| Own smartphone | −0.03 | 0.49 |

| Hours devoted to school | 0.00 | 0.91 |

| Google use frequency | −0.02 | 0.30 |

| UpToDate use frequency | 0.00 | 0.70 |

The table shows a multivariable linear regression with average daily topic viewing frequency (natural logarithm transform) as the dependent variable. The dependent variable was calculated as ‘number of UpToDate topics viewed’ / ‘days with an active subscription’ for each user. It was set to zero for users who did not log on to UpToDate. The dependent variable was transformed with the equation Y’=ln(Y+1) to approximate normality. The independent variables were set as follows: ‘Cohort’ was set to one for students enrolling in 2015–2016 and 2 for student enrolling in 2016–2017. ‘Year at enrolment’: PCL1 was set to 1, PLC2 was set to 2, Doc1 was set to 3, Doc3 was set to 5 and Doc4 was set to 6. ‘Own any device’ and ‘Own smartphone’ were set to 0 if the student did not report ownership and to 1 if they did. ‘Hours devoted to school’ is a sum of student reported hours spent in the classroom, in clinical activities, and on studying. ‘Google use frequency’ and ‘UpToDate use frequency’ were set based on student responses at the time of enrolment (before UpToDate subscriptions were given to them). They were set to 4 if student replied ‘almost every day’, 3 if ‘a few times per week’, 2 if ‘a few times per month’, 1 if ‘a few times per year’ and 0 if ‘never’ or ‘i don’t know this resource'. P value bolded if <0.05.

Figure 2.

Predictor of UpToDate usage. The average daily usage during the study period by UR students broken down by class year at enrolment. Students who did not log onto their accounts after enrolling into the study were assigned a daily topic viewing frequency of zero. n=547 UR students. UR, University of Rwanda.

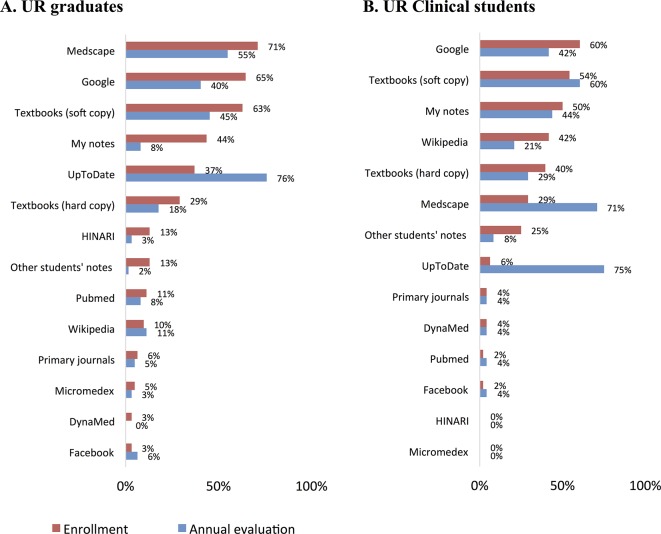

One year after enrolment, 52% of students completed the annual evaluation; 74% of Doc4 students did so. The low response rates could be attributed to lack of positive incentives to complete the survey or to students not checking their email to see that the evaluation survey was due. Both graduates, who had enrolled in the study as Doc4 students, and continuing students reported increased usage of UpToDate. Continuing students also reported decreased use of Google and Wikipedia (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Changes in the usage of electronic resources. Figures show the percentage of respondents who reported using a particular resource ‘almost every day’ at enrolment and 1 year later at the time of annual evaluation. Shading added to highlight responses for UpToDate. (A) Responses of UR users who had graduated at the time of annual evaluation and were practising physicians. (B) Responses of UR clinical students (Doc1 at the time of enrolment) who were still in school at the time of annual evaluation. n=62 UR graduates, and 66 UR students. UR, University of Rwanda.

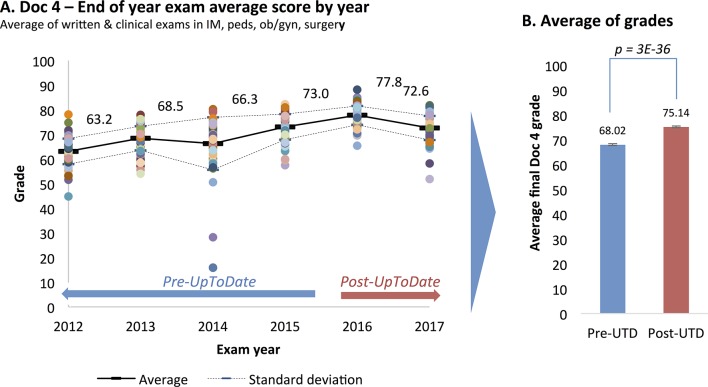

To assess the effect of providing UpToDate to students on their educational performance, we plotted the average grades of each graduating class from 2012 to 2017 (599 students in total) and compared the pre-UpToDate period (2012–2015; average grade 68) to the post-UpToDate period (2016–2017; average grade 75) (figure 4). Both a simple t-test as well as a two-way ANOVA showed a statistically significant difference (table 2). In 2017, a student who scored 68 would have ranked at the 16th percentile of the class, while a student scoring 75 would have ranked at the 66th percentile.

Figure 4.

Impact of EBCR provision on class exam performance at UR. (A) The average grades of graduating Doc4 students over time. Each dot represents one student and shows the average of their grades in the following eight exams: written and clinical exams in internal medicine, paediatrics, obstetrics and gynaecology and surgery. (B) The average grades of students pre-UpToDate (UTD) (2012–2015) and post-UpToDate (2016–2017). The p value represents a two-sided heteroscedastic t-test. The error bars represent standard error of the mean. EBCR, evidence-based clinical resource.

Table 2.

Two-way ANOVA with average Doc4 grade as dependent variable

| Independent variable | Partial SS | P value |

| UpToDate offered * | 4197 | <10−4 |

| Year of exam | 6196 | <10−4 |

The table shows a two-way ANOVA test with average Doc4 grade as dependent variable and year of exam and UpToDate provision as independent variables. n=599 Doc4 students over 6 years.

*UpToDate offered was set to 0 for 2012–2015 and 1 for 2016–2017.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; SS, sum of squares.

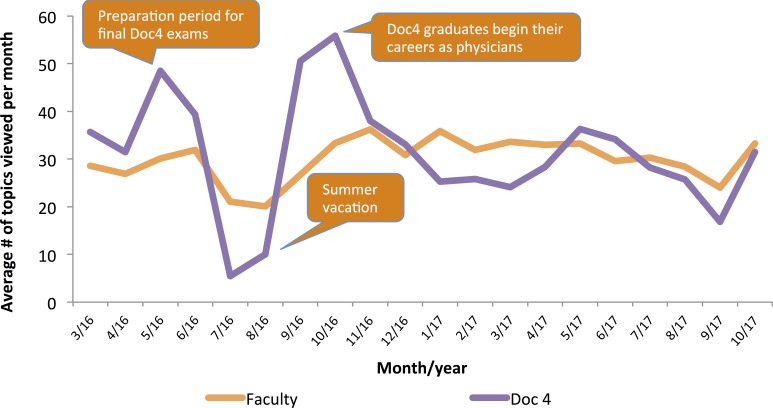

We used remote tracking to assess Doc4 student usage over time and found that it spiked in May 2016, as students prepared for their graduation exams in June. Usage fell significantly during summer vacation, but rose again in September and October, as the new graduates began their careers as physicians, either in residency or independent practice. A similar pattern of usage over time was seen among faculty (figure 5).

Figure 5.

EBCR utilisation over time by UR students and faculty. Lines show the average number of topics viewed per user per month by each user group. Only users who enrolled before 01 March 16 are included in this analysis (n=185 faculty, 70 Doc4 students). Call-outs are added to describe events in the careers of Doc4 students.

Discussion

Our findings represent the first prospective cohort study of medical students in Africa and suggest that access to devices and the internet might not be a significant barrier for African medical students wishing to access online resources. Our findings align with observations from a 2016 study in Zimbabwe and contrast two earlier studies in Nigeria published in 2004 and 2008 that suggest lack of access to internet.20-22 The differences might be related to the passage of time or resource availability differences between Rwanda and Nigeria. The findings suggest that, in Rwanda, our focus should not be on securing devices but on securing access to the latest online tools and evidence.

Our study also shows that students, especially final year students, used a leading EBCR frequently when the cost barrier was removed. This was achieved with no provision of internet-capable devices, no subsidising of mobile internet data, no dedicated training activities on EBCR use or evidence searching and no curricular integration of EBCRs. Overall, our findings suggest that removing the subscription cost barrier to access of EBCRs can generate uptake among a subset of medical students in East Africa. The low uptake of UpToDate by preclinical UR students could be related to the basic science focus of their curriculum, which makes UpToDate’s clinical content less relevant.

The introduction of an EBCR during the last year of medical school may lead to habit formation. Among students receiving an EBCR subscription in their final year, usage was sustained for the one and a half year period monitored after graduation. Additionally, self-reported usage of non-validated sources such as Google and Wikipedia fell among students within a year of UpToDate provision. In 2013, Gawande argued that habit change and formation in healthcare is a complex process that can often take decades.23 He also argued that some habits form quickly and that those might be the ones that make a physician’s workflow faster and more efficient. Our study suggests that UpToDate may fall into this category of tools and habits that facilitate faster, more efficient work.

The temporal association of free access to UpToDate with an improvement of the overall examination performance of the graduating class may be causal or due to another explanation, as discussed below. It is consistent, however, with previous reports of associations between UpToDate usage and performance in exams by residents in the US and Japan and practising physicians in the US.

Limitations

Our study is subject to selection bias, given its observational nature. It is possible that students with regular access to email were more likely to respond to our email-based invitation, thus biassing the response set, especially with respect to the use of electronic resources and internet access. The high enrolment rate among Doc4 students mitigates this effect to some extent.

The use of a historical control to assess the impact of UpToDate’s introduction on student grades also has several limitations. First, no causal arguments can be made, given the fact that different exams were used each year and different students took them. While UpToDate may have helped students prepare for their exams more efficiently and increase their knowledge base, it is also possible that the exams in 2016 and 2017 were easier than those of years past or that the students were independently academically superior to the previous classes. The cause of the overall increase in student scores before UpToDate was introduced is unclear and could be related to changes in educational methods or examinations, although we do not have evidence for either of those. In addition, the reason for the decline of students’ scores from 2016 to 2017 is unknown and could be statistically random or indicative of a trend. Further follow-up will be required to answer this question.

Second, it is possible that test answers may not be contained/addressed in UpToDate, although the UR faculty among the authors of this paper do not believe that to be the case.

Next steps

Due to its longitudinal nature, this study has the potential to offer additional insights on the changes in learning behaviours of African health trainees over time. Qualitative research on this student cohort could help elucidate the drivers of different study behaviours and the perceived impact of resources such as UpToDate on clinicians' knowledge base and self-efficacy.

Future research might explore other EBCRs and features that impact uptake and utility. We focused on UpToDate because of the body of literature that supports its value in high-income countries. However, we hypothesise that a suite of EBCRs and learning tools, possibly in multiple languages, might be helpful for trainees in LMICs. Given the relatively easy scalability of software-based tools, we believe that we can continue to decrease the barriers for trainees in LMICs to access the best available evidence at the frontline of care delivery. Our vision is that this work can prepare and inform how the next generation of clinicians in LMICs practices evidence-based medicine. Although our research focused on LMICs, disparities in access to high-quality EBCRs might exist within US medical education as well, which can also be an area of future research and programming. As medicine continues to evolve rapidly and medical education shifts its focus from memorisation to critical processing of information, we must ensure that all learners have equitable access to the best information available.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Peter Bonis, Dr Denise Basow, Denise Gilpin, Dr Ellie Baron, Becky Mueller and Bin Cao at Wolters Kluwer for their generous support of this work. They would also like to thank Marie Teichman, Teresa Oszkinis, Elissa Dakers and Fatima Fairfax for logistical support of this study. Finally, the authors wish to thank Dr Kate Miller and Dr Shelley Hurwitz for statistical expertise and guidance. This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst, The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR001102) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Contributors: YKV, JR, KW, RK, FM, RCM, TDW and RW designed the study and co-wrote its protocol. JDK, AE and BN implemented the study at the University of Rwanda. YKV analysed the data and drafted this manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript. RW oversaw the entire design, implementation and analysis of the study.

Funding: Wolters Kluwer donated the free UpToDate subscriptions. YKV received funding from the Alexander Onassis Foundation, the Harvard Medical School Abundance Fund and the Scholars In Medicine Office at Harvard Medical School. Global Health Delivery staff were supported by the Abundance Fund. Wolters Kluwer did not provide any monetary support to this study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The research described here was approved by the Harvard Medical School Longwood Medical Area Institutional Review Board and the College of Medicine and Health Sciences University of Rwanda Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Trends, Charts, and Maps. 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/resources/trends#RegisteredStudiesOverTime (cited 2018 Jan 12).

- 2. Schwartzstein RM, Roberts DH. Saying Goodbye to Lectures in Medical School - Paradigm Shift or Passing Fad? N Engl J Med 2017;377:605–7. 10.1056/NEJMp1706474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weinberger SE. Opening the Book on Maintenance of Certification. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:353–4. 10.7326/M17-1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. LCME Website [Internet]. Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and Structure of a Medical School. 2016. Available from: http://lcme.org/publications/ (cited 12 Jan 2018).

- 5. Mullan F, Frehywot S, Omaswa F, et al. Medical schools in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2011;377:1113–21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61961-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McDonald FS, Zeger SL, Kolars JC. Factors associated with medical knowledge acquisition during internal medicine residency. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:962–8. 10.1007/s11606-007-0206-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shimizu T, Nemoto T, Tokuda Y. Effectiveness of a clinical knowledge support system for reducing diagnostic errors in outpatient care in Japan: A retrospective study. Int J Med Inform 2018;109:1–4. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holmer H, Lantz A, Kunjumen T, et al. Global distribution of surgeons, anaesthesiologists, and obstetricians. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S9–11. 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70349-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bower JH, Zenebe G. Neurologic services in the nations of Africa. Neurology 2005;64:412–5. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150894.53961.E2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nolan T, Angos P, Cunha AJ, et al. Quality of hospital care for seriously ill children in less-developed countries. Lancet 2001;357:106–10. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03542-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mullan F, Frehywot S, Omaswa F, et al. Medical schools in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2011;377 1113–21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61961-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. UpToDate website [Internet]. Wolters Kluwer. Editorial. 2017. https://www.uptodate.com/home/editorial (cited 12 Jan 2018).

- 13. US News & World Report Website [Internet]. US News & World. 2018 Best Medical Schools: Research. 2017. https://www.usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-medical-schools/research-rankings?int=af3309&int=b3b50a&int=b14409 (cited 12 Jan 2018).

- 14. Personal Communication. Top 20 US Research Medical Schools, as ranked by US News & World Report in 2017 were contacted by email and asked whether they offer UpToDate access to their medical students.

- 15. World Bank Website [Internet]. The World Bank. Health Expenditure per capita. 2017. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.PCAP (cited 12 Jan 2018).

- 16. MTN Website [Internet]. MTN. MTN Mobile Internet. 2019. http://www.mtn.co.rw/Content/Pages/79/MTN_Mobile_Internet (cited 19 Feb 2019).

- 17. Valtis YK, Rosenberg J, Bhandari S, et al. Evidence-based medicine for all: what we can learn from a programme providing free access to an online clinical resource to health workers in resource-limited settings. BMJ Glob Health 2016;1 e000041 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. UR Website [Internet]. University of Rwanda Planning M&E Unit. Facts and Figures. 2017. http://ur.ac.rw/sites/default/files/Facts%20and%20Figures-2017-Final%20to%20be%20published.pdf#overlay-context= (cited 12 Jan 2018).

- 19. Mazloomdoost D, Mehregan S, Mahmoudi H, et al. Perceived barriers to information access among medical residents in Iran: obstacles to answering clinical queries in settings with limited Internet accessibility. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2007;11:523–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bello IS, Arogundade FA, Sanusi AA, et al. Knowledge and utilization of Information Technology among health care professionals and students in Ile-Ife, Nigeria: a case study of a university teaching hospital. J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e45 10.2196/jmir.6.4.e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Odusanya OO, Bamgbala OA. Computing and information technology skills of final year medical and dental students at the College of Medicine University of Lagos. Niger Postgrad Med J 2002;9:189–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parve S, Ershadi A, Karimov A, et al. Access, attitudes and training in information technologies and evidence-based medicine among medical students at University of Zimbabwe College of Health Sciences. Afr Health Sci 2016;16:860–5. 10.4314/ahs.v16i3.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gawande A. Slow Ideas. The New Yorker, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026947supp001.pdf (66.7KB, pdf)