Abstract

Objectives

Examination of the prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among the elderly in China.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

More than 10 000 households in 28 of the 34 provinces of mainland China.

Participants

11 707 Chinese adults aged 60 and over.

Primary outcome measures

Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among the participants. Relative risks were calculated to estimate the probability of up to 14 chronic conditions coexisting with each other. Observed-to-expected (O/E) ratios were used to analyse the patterns of multimorbidity.

Results

Multimorbidity was present in 43.6% of respondents from the sample population, with women having the greater prevalence compared with men. There were 804 different comorbidity combinations identified, including 76 dyad combinations and 169 triad combinations. The top 10 morbidity dyads and triads accounted for 69.01% and 47.05% of the total dyad and triad combinations observed, respectively. Among the 14 chronic conditions included in the study, asthma, stroke, heart attack and six other chronic conditions were the main components of multimorbidity due to their high relative risk ratios. The most frequently occurring clusters with higher O/E ratios were stroke along with emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems; memory-related diseases together emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems; and memory-related diseases and asthma accompanied by chronic lung diseases and asthma.

Conclusions

The results of this study highlight the high prevalence of multimorbidity in the elderly population in China. Further studies are required to understand the aetiology of multimorbidity, and future primary healthcare policies should be made while taking multimorbidity into consideration.

Keywords: multimorbidity, cross-sectional study, prevalence, observed-to-expected ratio, China

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to estimate the prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among the elderly population in China.

Data for this study were collected from a nationally representative longitudinal survey of 17 708 Chinese residents.

Only 14 predefined chronic diseases were included in the study, and these may not be comprehensive of the conditions of the population.

The data analysed from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey were originally collected by population self-reporting, not clinician evaluation, and could partially reflect some associated biases or confounds.

This study only included older patients aged 60 years and above with complete data. Although exclusion of incomplete data may cause a selection bias, significant differences between included and excluded cases were not observed.

Introduction

Multimorbidity, or the simultaneous occurrence of two or more chronic conditions in an individual, is becoming increasingly common, and this has been reported to increase progressively with age.1 2 At present, with China’s ageing population having an increasing prevalence of chronic conditions, multimorbidity among the elderly poses an enormous societal cost due to increased mortality rates and healthcare utilisation.3 However, to date, research on chronic conditions in China has focused on single disease states, and the coexistence of multiple chronic conditions (MCC) has not been investigated systematically and thoroughly.

There is a significant difference in the aetiological analysis between patients with single chronic conditions and those with multimorbidity.4 The coexistence of chronic conditions in a patient is more than a random event, it is more typically due to the causal relationship between some diseases and shared pathogenic factors.5 6 Moreover, the interactions between diseases or between a disease and host result in differences in the severity of multimorbidity and functional status and prognosis of patients with multimorbidity.7 Consequently, it is imperative to begin research on multimorbidity in China for the cost-effective treatments that the results may help to suggest.8 The purpose of this study was therefore to determine the prevalence of multimorbidity among the elderly in China and to reveal morbidity combinations, which may benefit the design and implementation of a modified healthcare system with consideration for patients with multimorbidity.

Methods

Data source

Data for this study were collected from the third response of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey (CHARLS), which is the most current data available. The CHARLS is a nationally representative longitudinal survey of Chinese residents aged 45 and older that was conducted by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, along with Peking University, to help China to adjust to the rapid ageing of its population through the evaluation of social, economic and health circumstances on the community level using data collected by interviews, physical measurements and blood sample collection.9 The national baseline survey began in 2011 and involved 17 708 respondents from 150 county-level units, 450 village-level units and approximately 10 000 households. Afterwards, CHARLS respondents were followed every second year, with their informed consent, and the study was approved by the Peking University Biomedical Ethics Committee (IRB00001052-14013-exemption).

Variables

The core CHARLS questionnaires included sections requesting information on demographic factors, family structure and changes, health status and functioning, healthcare and insurance, work, retirement and pension, income and consumption, and assets (individual and household). Information was collected by interview by trained staff. For the current study, the eligible and included participants were determined by being aged 60 and over, and data on gender, age and health status was used from the general health status and disease history section of senior citizens in the 2015 CHARLS data. This information included the following 14 common chronic health problems: hypertension, dyslipidaemia (high blood lipids or low cholesterol), diabetes or elevated blood glucose (including impaired glucose tolerance and fasting blood glucose), cancer (excluding mild skin cancers), chronic lung disease such as chronic bronchitis or emphysema, pulmonary heart disease (excluding tumours or cancer), liver disease (other than fatty liver, tumours, or cancer), heart disease (such as myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, angina pectoris, congestive heart failure and other heart diseases), stroke, kidney disease (excluding tumours or cancer), stomach or other digestive diseases (excluding tumours or cancer), emotional and mental problems, memory-related diseases (such as Alzheimer’s disease, brain atrophy, Parkinson’s disease), arthritis or rheumatism and asthma. All these data were based on self-reports. Accordingly, multimorbidity was defined as the coexistence of more than one of the 14 chronic conditions, with acute or subacute forms of certain conditions being excluded in this study due to the CHARLS data collection protocol.

Statistical analysis

To detect the demographic characteristics of patients with multimorbidity, respondents were divided into two groups: those with MCC group and those without multiple chronic conditions (non-MCC group). Descriptive statistics were calculated and expressed as means (SD) and frequencies (percentage). We applied the T2 and 2 tests to test the differences in age, gender and the mean number of chronic conditions across different subgroups. Respective prevalence in the MCC group and the non-MCC group were calculated separately. Given the exclusion of participants with incomplete data, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to compare the characteristics of the complete cases aged 60 years and above and the counterpart in the incomplete cases, which is presented in online supplementary annex 1.

bmjopen-2018-024268supp001.pdf (56.4KB, pdf)

To determine the most common combination of chronic diseases, the prevalence of morbidity and multimorbidity dyads and triads were estimated, respectively. Next, the expected number of patients with a chronic disease were calculated, and the observed-to-expected (O/E) ratios were determined by dividing the number of patients in those groups by the expected number of patients. O/E ratios were used to estimate the conditional probability of coexistence of two or three chronic conditions.10 As an important indicator for assessing the correlation between diseases, the O/E ratio has been used in many areas of comorbidity.10 11 The relative risk of comorbidity for individual chronic conditions was also calculated. Relative risk of comorbidity (RR) is the ratio of the number of people with a certain chronic condition who suffer from multimorbidity to the number of patients with the same disease who do not suffer from multimorbidity.11 12 In other words, a higher RR value means a higher probability that the disease coexists with other diseases. However, it should be noted that there is no direct relationship between the RR and the overall prevalence of the diseases.13 14

All analyses in this study were completed using Stata software V.14.0 for Windows. P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the development of the research question or outcome measures of the study, nor were they involved in study design and execution. There are no plans to disseminate the research results to study participants.

Results

Characteristics of participants

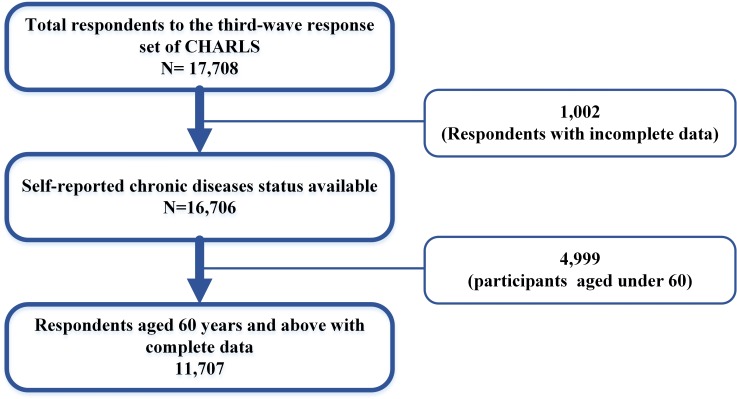

The data were gathered from the third response set of CHARLS. After exclusion of participants with incomplete data (1002) or aged under 60 (9259), there were 11 707 respondents with available information on related chronic diseases that were included in this study. The selection process of study sample is shown in figure 1. The demographic characteristics of sample respondents and statistical significance test results are presented in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for selecting the study sample from the original sample population. CHARLS, China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of all respondents, the multiple chronic conditions (MCC) group and non-MCC group

| All respondents | MCC group | Non-MCC group | P* | |

| Number of people | 11 707 | 5107 | 6600 | |

| Proportion (%) | 100% | 43.62% | 56.38% | |

| Mean age | ||||

| All respondents (SD) | 70.20 (7.907) | 70.57 (7.701) | 69.91 (8.051) | <0.001 |

| Male (SD) | 69.97 (7.575) | 70.50 (7.348) | 69.60 (7.707) | <0.001 |

| Female (SD) | 70.39 (8.189) | 70.62 (7.892) | 70.19 (8.359) | <0.001 |

| Gender (% females) | 51.28% | 54.41% | 48.83% | <0.001 |

| Mean number of chronic conditions | ||||

| All respondents (SD) | 1.57 (1.560) | 3.01 (1.259) | 0.45 (0.498) | <0.001 |

| Male (SD) | 1.47 (1.534) | 2.98 (1.265) | 0.44 (0.496) | <0.001 |

| Female (SD) | 1.65 (1.581) | 3.03 (7.982) | 0.47 (0.499) | <0.001 |

t-tests were performed for comparison of means and χ2-tests for differences between percentages.

*Statistical significance of the difference between the MCC and the non-MCC sample.

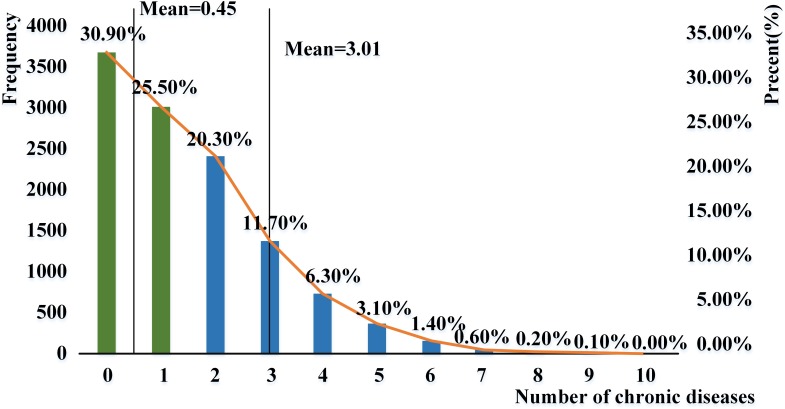

Overall, the mean age for the sample population was 70.5 (ranging from 60 to 107). The sample population consisted of 5705 (48.7%) males and 6002 (51.2%) females, and 43.6% of them suffered from multimorbidity. The median of chronic conditions in the MCC group was 3.01, compared with 0.45 in the non-MCC group. Samples in the MCC group were 0.66 year older than those belonged to the non-MCC group. Gender differences with regard to the age of samples between the MCC group and the non-MCC group (70.57 for MCC group and 69.51 for non-MCC group) were small but statistically significant (p<0.001). The prevalence of multimorbidity in the female population was higher than that for the males (54.41% vs 45.59%). Figure 2 shows the number and proportion of respondents over 60 according to morbidity numbers. It can be seen that among all the participants aged over 60, only 30.9% of them did not have the 14 chronic diseases and 43.6% suffer from multimorbidity.

Figure 2.

Frequency and percentage of people aged over 60 suffering from different diseases based on China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey data.

Prevalence of chronic conditions

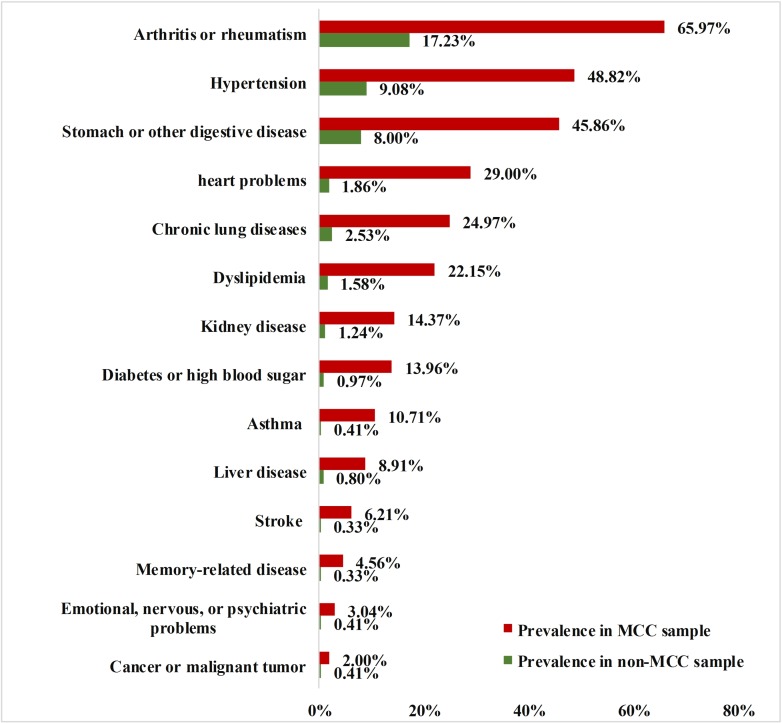

The prevalence of chronic conditions in the entire sample, the MCC group and the non-MCC group are shown in figure 3. The prevalence of all 14 chronic conditions in the MCC group was significantly higher than that in the entire sample. For instance, the prevalence of arthritis or rheumatism, hypertension, stomach or other digestive disease, heart disease and chronic lung disease were 65.97%, 48.82%, 45.86%, 29.00% and 24.97% in the MCC group, compared with 38.49%, 26.41%, 24.52%, 12.32% and 12.32% in the entire sample, respectively.

Figure 3.

Prevalence rates of chronic condition in elderly people over 60 years old based on China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey data. MCC, multiple chronic conditions.

Table 2 shows the relative risks of comorbidity determined for the 14 chronic diseases reported in this study. It can be seen that the overall relative risks for asthma, stroke, heart disease and six other conditions were all above 10, which meant these diseases were >10 times easier to coexist with other chronic conditions and result in multimorbidity. In addition, the relative risks for certain diseases were positively associated with gender. For example, men had significantly higher relative risks for asthma, but lower relative risks for diabetes or high blood sugar, compared with women.

Table 2.

Relative risks of multimorbidity for different chronic conditions according to gender

| Chronic conditions | All respondents | 95% CI | Female | 95% CI | Male | 95% CI | |||

| Lower bound | Upper bound | Lower bound | Upper bound | Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||

| High relative risk of multimorbidity | |||||||||

| Asthma | 26.18 | 17.82 | 38.46 | 20.67 | 11.85 | 36.06 | 32.68 | 19.18 | 55.67 |

| Stroke | 18.62 | 12.11 | 28.64 | 21.57 | 10.61 | 43.86 | 17.43 | 10.13 | 29.99 |

| Heart disease | 15.56 | 12.99 | 18.63 | 16.48 | 12.80 | 21.21 | 14.26 | 11.02 | 18.46 |

| Diabetes or high blood sugar | 14.40 | 11.18 | 18.55 | 15.68 | 10.86 | 22.63 | 13.11 | 9.24 | 18.62 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 14.05 | 11.54 | 17.12 | 15.13 | 11.37 | 20.14 | 12.97 | 9.86 | 17.05 |

| Memory-related disease | 13.69 | 8.85 | 21.16 | 34.17 | 12.63 | 92.44 | 9.28 | 5.66 | 15.21 |

| Kidney disease | 11.57 | 9.24 | 14.49 | 15.01 | 10.17 | 22.43 | 10.24 | 7.78 | 13.48 |

| Liver disease | 11.10 | 8.37 | 14.71 | 16.07 | 9.70 | 26.63 | 9.15 | 6.49 | 12.89 |

| Chronic lung diseases | 9.87 | 8.43 | 11.55 | 10.71 | 8.26 | 13.88 | 9.74 | 8.00 | 11.86 |

| Low relative risk of multimorbidity | |||||||||

| Emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems | 7.42 | 4.94 | 11.15 | 6.24 | 3.78 | 10.30 | 9.36 | 4.65 | 18.85 |

| Stomach or other digestive disease | 5.73 | 5.25 | 6.25 | 6.20 | 5.48 | 7.02 | 5.23 | 4.62 | 5.91 |

| Hypertension | 5.38 | 4.96 | 5.84 | 4.90 | 4.40 | 5.47 | 5.92 | 5.24 | 6.69 |

| Cancer or malignant tumour | 4.88 | 3.20 | 7.45 | 5.33 | 3.06 | 9.29 | 3.99 | 2.07 | 7.72 |

| Arthritis or rheumatism | 3.83 | 3.61 | 4.05 | 3.70 | 3.43 | 3.99 | 3.91 | 3.59 | 4.26 |

Common multimorbidity combinations

There were 804 possible comorbidity combinations that were identified in the MCC group after statistical analysis, including 72 dyads and 169 triads. The 10 most frequently occurring morbidity dyads and triads are presented respectively in tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Prevalence of the 10 most common morbidity dyads

| Rank | Morbidity dyads | Prevalence | Mean age | ||

| All respondents (%) | Female (%) | Male (%) | |||

| 1 | Arthritis or rheumatism and stomach or other digestive disease | 4.73 | 3.56 | 5.96 | 69.20 |

| 2 | Arthritis or rheumatism and hypertension | 2.85 | 2.20 | 3.53 | 71.25 |

| 3 | Arthritis or rheumatism and chronic lung diseases | 1.13 | 1.22 | 1.04 | 71.55 |

| 4 | Hypertension and heart problems | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 71.80 |

| 5 | Hypertension and stomach or other digestive disease | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.95 | 69.07 |

| 6 | Hypertension and dyslipidaemia | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.91 | 68.58 |

| 7 | Arthritis or rheumatism and heart problems | 0.76 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 70.72 |

| 8 | Arthritis or rheumatism and kidney disease | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.54 | 68.24 |

| 9 | Hypertension and diabetes or high blood sugar | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 70.97 |

| 10 | Chronic lung diseases and asthma | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.40 | 71.15 |

Table 4.

Prevalence of the 10 most common morbidity triads

| Rank | Morbidity triads | Prevalence | Mean age | ||

| All respondents (%) | Female (%) | Male (%) | |||

| 1 | Arthritis or rheumatism, stomach or other digestive disease and hypertension | 1.19 | 0.80 | 1.60 | 70.96 |

| 2 | Arthritis or rheumatism, stomach or other digestive disease and chronic lung diseases | 0.82 | 0.97 | 0.67 | 70.82 |

| 3 | Arthritis or rheumatism, heart disease and hypertension | 0.63 | 0.37 | 0.91 | 69.93 |

| 4 | Arthritis or rheumatism, heart disease and stomach or other digestive disease | 0.59 | 0.25 | 0.95 | 71.51 |

| 5 | Hypertension, dyslipidaemia and arthritis or rheumatism | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.57 | 70.13 |

| 6 | Hypertension, dyslipidaemia and Heart problems | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 71.17 |

| 7 | Arthritis or rheumatism, kidney disease and stomach or other digestive disease | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 70.14 |

| 8 | Arthritis or rheumatism, asthma and chronic lung diseases | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 69.18 |

| 9 | Hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes or high blood sugar | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 71.51 |

| 10 | Arthritis or rheumatism, stomach or other digestive disease and liver disease | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 70.29 |

Theoretically, there are 91 dyad combinations and 364 triad combinations possible given the 14 different chronic conditions considered in this study. However, only 72 types (79.12%) of dyads and 169 types (46.43%) of triads emerged in the sample. The 10 most frequently occurring morbidity dyads accounted for 69.01% of the 72 dyad combinations, and the proportion of the 10 most common triad combinations in the 169 triad combinations was 47.05%. Arthritis or rheumatism, which appeared in five of the top 10 dyad combinations and eight of the top 10 triad combinations of chronic conditions, was the main component of the leading morbidity dyads and triads.

There were significant gender differences observed in the occurrences of these multimorbidity combinations. The numbers of women with triad combinations of chronic diseases were generally higher than for men with the same morbidity triads. For example, women had significantly higher prevalence of arthritis and hypertension and hyperlipidaemia than men (78.26% vs 21.74%). Among morbidity dyads, the prevalence of heart disease and arthritis or rheumatism in women was nearly two times higher than that in men, while the cluster of arthritis or rheumatism and kidney disease occurred more frequently in men than in women. No age difference was detected in the probability of these particular multimorbidity combinations occurring.

The O/E ratio was also used to analyse the multimorbidity pattern.15 The higher the O/E value, the higher the probability of coexistence of chronic conditions.16 Table 5 shows O/E ratios determined for the 10 most prevalent morbidity dyads and triads. The prevalence of each conditions and the dyad and triad prevalence are presented in online supplementary annex 2. In the midst of those triad combinations of chronic conditions, the two clusters with significantly higher O/E ratios were emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems and stroke and memory-related disease (O/E ratio=10 287.72), emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems and memory-related disorders and asthma (O/E ratio=8498.56). These four conditions also dominated the three leading dyads with the highest O/E ratios: 97.73 for the combination of emotional and mental disorders and memory-related diseases, 23.66 for the combination of stroke and memory related disease and 19.55 for the combination of memory-related disease and asthma.

Table 5.

O/E ratios for the 10 most prevalent morbidity dyads and triads

| Number of chronic conditions | Rank | Chronic conditions | O/E ratio |

| 2 | 1 | Chronic lung diseases and asthma | 162.15 |

| 2 | Emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems and memory-related disease | 97.73 | |

| 3 | dyslipidaemia and diabetes or high blood sugar | 38.39 | |

| 4 | Heart disease and memory-related disease | 25.69 | |

| 5 | Stroke and memory-related disease | 23.66 | |

| 6 | Hypertension and stroke | 22.85 | |

| 7 | Hypertension and diabetes or high blood sugar | 20.64 | |

| 8 | Cancer or malignant tumour and stroke | 19.55 | |

| 9 | Memory-related disease and asthma | 19.55 | |

| 10 | Stroke and asthma | 19.55 | |

| 3 | 1 | Stroke, emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems and memory-related disease | 10 287.72 |

| 2 | Emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems, memory-related disease and asthma | 8498.56 | |

| 3 | Emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems, chronic lung diseases and asthma | 2274.26 | |

| 4 | Heart disease, stroke and memory-related disease | 2253.50 | |

| 5 | Chronic lung diseases, heart disease and asthma | 1992.69 | |

| 6 | Dyslipidaemia, heart disease and memory-related disease | 1443.25 | |

| 7 | Hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes or high blood sugar | 1398.31 | |

| 8 | Hypertension, stroke and memory-related disease | 1387.35 | |

| 9 | Chronic lung diseases, memory-related disease and asthma | 1376.53 | |

| 10 | Chronic lung diseases, arthritis or rheumatism and asthma | 1265.95 |

O/E, observed-to-expected.

bmjopen-2018-024268supp002.pdf (77.4KB, pdf)

Discussion

This is the first study to estimate the prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among the elderly in China based on the nationally representative data from CHARLS, which included 11 707 older patients aged 60 years and above with complete data. Although exclusion of incomplete data may cause a selection bias, significant differences between included and excluded cases were not observed. The results of the study indicated that 69.1% of the elderly population in China had at least one of the 14 diseases and 43.6% of them suffered from multimorbidity. The average age of the MCC group was 0.66 years higher than that of the non-MCC group and in the MCC group, the mean age of women was 0.12 years higher than that of men, which was comparable to the results of previous studies.17–21

The prevalence of multimorbidity estimated in this study was much lower than that from previous studies in other developed countries. For example, a study of 543 patients over age 65 in Ghent, Belgium showed that the multimorbidity rate was as high as 82.6%.22 Another study in Australia showed that 83.2% of the respondents suffered from multimorbidity.23 However, it is difficult to compare the prevalence generated from different studies due to differences in the selected definitions of multimorbidity, demographic characteristics of the samples and different study methodologies.1 24–27

In agreement with previous reports, arthritis or rheumatism, hypertension, stomach or other digestive disease were the most common diseases in the MCC group.11 The prevalence of these three conditions was each above 20% in the entire sample, and above 45% in the MCC group. The most prevalent chronic combinations in the sample could also be found in other studies.22 The results of this study showed that the prevalence of arthritis or rheumatism was high and easy to coexist with other conditions. In addition to the chronic conditions mentioned above, previous studies demonstrated that women with rheumatoid arthritis might have a predisposition to gallstones which could manifest in middle or older age compared with women in the general population. This phenomenon could be related to chronic inflammation and HDL metabolism.28

Although arthritis or rheumatism, a component of all the leading three morbidity dyads and triads, was also the most commonly occurring disease in multimorbidity, the relative risk of this disease was only 4.65, the lowest in the 14 chronic diseases. Moreover, arthritis or rheumatism is less common in morbidity clusters with large O/E ratios. Therefore, the frequent occurrence of arthritis or rheumatism in multimorbidity might be simply due to the high prevalence of the disease. Doctor-diagnosed arthritis is a common and disabling chronic condition in the world. During 2013–2015, an average of more than one in five (54.4 million) adults in the USA were diagnosed with arthritis.29 The unadjusted prevalences of arthritis among adults with obesity, heart disease, or diabetes were 30.6%, 49.3% and 47.1%, respectively. In adults with obesity, heart disease, or diabetes, the age-adjusted prevalences of arthritis were respectively 1.5, 1.7 and 1.9 times higher than those without these diseases. Improving the health of adults with arthritis and related comorbid conditions calls for wider dissemination and implementation of evidence-based interventions, such as self-management education and physical activity promotion.30

The relative risks for asthma, stroke, heart disease, and six other conditions were all above 10, which means that patients with these diseases were 10 times more likely to be afflicted by multimorbidity. These diseases also occurred at a high frequency in multimorbidity with high O/E ratios, such as the clusters of pulmonary disease and asthma, emotional and mental illness and memory-related disease, dyslipidaemia and diabetes, and stroke and emotional or mental illness and memory-related disease. Patients with these diseases were more likely to express comorbidity compared with those without these diseases, and thus should be the focus of future research studies.

This study featured a nationally representative sample of the Chinese elderly population, which was crucial to get an overall understanding of multimorbidity among the elderly in China. However, there were also limitations with the data sample and study. For example, this study used data from the third wave report of CHARLS, a survey which was conducted in 2015, and there is accordingly a time lag to now that exists. Additionally, the chronic diseases included in the study were not comprehensive, since only 14 chronic conditions were included in the survey. Finally, the data obtained from the survey was based on self-reporting, which may have introduced some misclassification bias or other confounds. Later research on the prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity should be carried out in-depth with a more extensive survey of chronic disease.

Conclusions

Multimorbidity remains an underexplored area of research in China.31 Despite the increasing prevalence of multimorbidity, there are no specific proposals for its diagnosis and treatment.32 This study contributes to the understanding of the prevalence and patterns of comorbidity among the elderly in China. Considering China’s ageing population and the high prevalence of comorbidity in senior citizens, the elderly should be prioritised in the fields of disease prevention and health promotion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention and Peking University for access to China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey data.

Footnotes

Contributors: RZ analysed and interpreted data, drafted the manuscript, approved the final manuscript as submitted. YL revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. LS analysed and interpreted data and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. SZ analysed and checked the data of the full text. FC helped on the study design and revised the manuscript.

Funding: This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (7167030838).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The original CHARLS was approved by the ethics review committee of Peking University, and all participants gave written informed consent at the time of participation.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet 2012;380:37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization Global status report on noncommunicable diseases, 2014. Available: http://apps.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-status-report-2014/en/index.html [Accessed 27 Oct 2017]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3. Lee JT, Hamid F, Pati S, et al. Impact of noncommunicable disease multimorbidity on healthcare utilisation and out-of-pocket expenditures in middle-income countries: cross sectional analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0127199–110. 10.1371/journal.pone.0127199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moffat K, Mercer SW. Challenges of managing people with multimorbidity in today’s healthcare systems. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:129 10.1186/s12875-015-0344-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ingmar S, Eike-Christin vonL, Gerhard S, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in the elderly: a new approach of disease clustering identifies complex interrelations between chronic conditions. PLoS One 2010;12:e15941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Atun R. Transitioning health systems for multimorbidity. The Lancet 2015;386:721–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62254-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2269–76. 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang L, Wu M, Cui B, et al. Economic burden of cardiovascular diseases in China. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2008;8:349–56. 10.1586/14737167.8.4.349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, et al. Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:61–8. 10.1093/ije/dys203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van den Bussche H, Koller D, Kolonko T, et al. Which chronic diseases and disease combinations are specific to multimorbidity in the elderly? results of a claims data based cross-sectional study in Germany. BMC Public Health 2011;11:101–10. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Viera AJ. Odds ratios and risk ratios: what's the difference and why does it matter? South Med J 2008;7:30–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vettore MV, Meira GdeF, Rebelo MAB, et al. Multimorbidity patterns of oral clinical conditions, social position, and oral health-related quality of life in a population-based survey of 12-yr-old children. Eur J Oral Sci 2016;124:580–90. 10.1111/eos.12304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang J, KF Y. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA 1998;19:1690–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McNutt L-A, et al. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:940–3. 10.1093/aje/kwg074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marengoni A, Rizzuto D, Wang H-X, et al. Patterns of chronic multimorbidity in the elderly population. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:225–30. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02109.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Best WR, Cowper DC. The ratio of Observed-to-Expected mortality as a quality of care indicator in non-surgical Va patients. Med Care 1994;32:390–400. 10.1097/00005650-199404000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kastenholz KE, Weis M, Hagelstein C, et al. Correlation of Observed-to-Expected MRI fetal lung volume and ultrasound Lung-to-Head ratio at different gestational times in fetuses with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2016;206:856–66. 10.2214/AJR.15.15018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Melis R, Marengoni A, Angleman S, et al. Incidence and predictors of multimorbidity in the elderly: a population-based longitudinal study. PLoS One 2014;9:e103120 10.1371/journal.pone.0103120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laan W, Bleijenberg N, Drubbel I, et al. Factors associated with increasing functional decline in multimorbid independently living older people. Maturitas 2013;75:276–81. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eckerblad J, Theander K, Ekdahl A, et al. To adjust and endure: a qualitative study of symptom burden in older people with multimorbidity. Applied Nursing Research 2015;28:322–7. 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wister A, Kendig H, Mitchell B, et al. Multimorbidity, health and aging in Canada and Australia: a tale of two countries. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:163–76. 10.1186/s12877-016-0341-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Afshar S, Roderick PJ, Kowal P, et al. Multimorbidity and the inequalities of global ageing: a cross-sectional study of 28 countries using the world health surveys. BMC Public Health 2015;15:776–86. 10.1186/s12889-015-2008-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boeckxstaens P, Peersman W, Goubin G, et al. A practice-based analysis of combinations of diseases in patients aged 65 or older in primary care. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:1–6. 10.1186/1471-2296-15-159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Britt HC, Harrison CM, Miller GC, et al. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Australia. Med J Aust 2008;2:72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Glynn LG, Valderas JM, Healy P, et al. The prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care and its effect on health care utilization and cost. Fam Pract 2011;28:516–23. 10.1093/fampra/cmr013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev 2011;10:430–9. 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fortin M, Stewart M, Poitras M-E, et al. A systematic review of prevalence studies on multimorbidity: toward a more uniform methodology. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:142–51. 10.1370/afm.1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. García-Gómez MC, De L E O-PS, et al. High Prevalence of Gallstone Disease in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A New Comorbidity Related to Dyslipidemia? [J]. Reumatol Clin 2017;14:294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barbour KE, Helmick CG, Boring M, et al. Vital signs: prevalence of Doctor-Diagnosed arthritis and Arthritis-Attributable activity limitation — United States, 2013–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:246–53. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6609e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ward BW, Schiller JS. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults: estimates from the National health interview survey, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;10:120203 10.5888/pcd10.120203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bao W, Hu D, Shi X, et al. Comorbidity increased the risk of falls in Chinese older adults: a cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Exp Med 2017;7:10753–63. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gao N, Yuan Z, Tang X, et al. Prevalence of CHD-related metabolic comorbidity of diabetes mellitus in northern Chinese adults: the reaction study. J Diabetes Complications 2016;30:199–205. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024268supp001.pdf (56.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024268supp002.pdf (77.4KB, pdf)