Abstract

The extracellular matrix (ECM) of the lung provides physical support and key mechanical signals to pulmonary cells. Although lung ECM is continuously subjected to different stretch levels, detailed mechanics of the ECM at the scale of the cell is poorly understood. Here, we developed a new polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) chip to probe nonlinear mechanics of tissue samples with atomic force microscopy (AFM). Using this chip, we performed AFM measurements in decellularized rat lung slices at controlled stretch levels. The AFM revealed highly nonlinear ECM elasticity with the microscale stiffness increasing with tissue strain. To correlate micro- and macroscale ECM mechanics, we also assessed macromechanics of decellularized rat lung strips under uniaxial tensile testing. The lung strips exhibited exponential macromechanical behavior but with stiffness values one order of magnitude lower than at the microscale. To interpret the relationship between micro- and macromechanical properties, we carried out a finite element (FE) analysis which revealed that the stiffness of the alveolar cell microenvironment is regulated by the global strain of the lung scaffold. The FE modeling also indicates that the scale dependence of stiffness is mainly due to the porous architecture of the lung parenchyma. We conclude that changes in tissue strain during breathing result in marked changes in the ECM stiffness sensed by alveolar cells providing tissue-specific mechanical signals to the cells.

Keywords: ECM micromechanics, Multiscale lung mechanics, AFM, Tensile testing

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The extracellular matrix (ECM) of the lung parenchyma is a complex filamentous network mainly composed of collagen, elastin and proteoglycans [1-3]. Collagen and elastin fibers form the primary load-bearing ECM components and are the main contributors to the elasticity and tensile strength of acellular lung tissue [2, 3]. The lung ECM defines the 3D tissue architecture which provides physical support to all resident pulmonary cells. Additionally, there is ample evidence that cells sense and actively respond to the rigidity of the extracellular microenvironment [4]. This cell-matrix mechanical interplay is a key determinant of critical cellular functions including migration, contraction, cell division and differentiation [5-9].

The mechanical features of cell microenvironment are especially important in the lung since its ECM is continuously subjected to cyclic stretching due to breathing. Moreover, alteration of ECM mechanics is correlated with severe respiratory diseases [10, 11]. Indeed, whereas ECM stiffening is a hallmark of lung fibrosis [12, 13], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, particularly emphysema, results in ECM softening and alveolar disruption [14, 15]. Moreover, alterations in the mechanical properties of the cells’ microenvironment have been linked to lung cancer [16-20]. However, there is a lack of experimental data and understanding of the micromechanical properties of lung ECM which is of paramount importance to better understand lung function in health and disease.

A common approach to study the mechanical behavior of acellular lung tissues at the macroscale is to measure the stress-strain relationship of parenchymal strips subjected to uniaxial stretching [21-25]. Macroscale tissue stiffness is characterized by the Young’s modulus computed as the slope of the stress-strain curve (EM). Uniaxial tensile tests of native tissue samples containing cells and ECM revealed a marked nonlinear behavior of lung tissues, with stiffness increasing approximately as an exponential function of strain [21]. Since stiffness of pulmonary cells is much smaller than that of lung tissues [26-28] the exponential nonlinear stress-strain relationship observed in lung tissues suggests a nonlinear macromechanical behavior of the lung ECM. A direct approach to probe ECM macromechanics freed from the cellular contribution is to study decellularized lung tissues [27, 29, 30]. However, macroscale mechanics of the acellular lung ECM is still poorly defined.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) proved to be a powerful tool to assess mechanical properties of ECM at the cell level scale. AFM probes micromechanical properties of the sample by indenting its surface with a microfabricated cantilever ended with a pyramidal or spherical tip [31]. This technique allows the measurement of tip displacement with nanometer resolution and simultaneous measurement of the applied force. As the AFM system can be mounted onto the stage of an inverted optical microscope, the tip can be precisely positioned at the point of interest. The force-indentation relationship defines the micromechanical properties of the sample. Microscale stiffness is characterized as the Young’s modulus computed by fitting the appropriate tip-sample contact model to the force-indentation curve (Em) [21, 23]. It should be noted, however, that commonly used contact models assume linear mechanics and that the size of the contact area is much smaller than the size of the surface sample. These conditions are challenged when probing the alveolar septum. Importantly, microscale lung ECM stiffness measured by AFM [27] has been reported to be one order of magnitude higher than macroscale stiffness measured in native lung parenchymal strips with tensile testing. This scale dependence of lung stiffness has been investigated using a model [23], but no experimental verification is available.

AFM measurements are currently performed in unstretched tissue samples. Nevertheless, under physiological conditions the lungs are permanently distended from its relaxed unstretched volume. Therefore, lung ECM is a prestressed structure whose mechanical behavior is determined by the level of tissue stretch. Despite the importance of knowing the micromechanical properties of the cell microenvironment under physiological conditions, to the best of our knowledge, no AFM measurements have been reported in lung ECM during stretch likely due to technical challenges. Considering the marked strain hardening behavior of lung tissues, we hypothesized that the stiffness of the cell microenvironment increases with tissue strain. However, direct measurement of the strain dependence of Em requires the development of new technology that allows the AFM to probe tissue samples subjected to different levels of stretch.

The aim of this work was to study the dependence of Em of the lung ECM on the magnitude of macroscale tissue strain. First, we designed a new polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) chip to stretch tissue and ECM slices. The chip can be easily coupled to a conventional AFM system and is compatible with inverted optical microscopy. Using this chip, we then performed micromechanical AFM measurements in decellularized rat lung slices subjected to different levels of stretch. To assess the effects of tip geometry and finite dimensions of the alveolar septum on AFM measurements, we probed ECM slices with both spherical and blunted pyramidal tips. Differences in AFM measurements obtained with spherical and blunted pyramidal tips were analyzed with finite element (FE) models of tip-tissue contact mechanics. To correlate micro- and macroscale ECM mechanics, we also probed decellularized lung parenchymal strips with uniaxial tensile testing. Finally, we interpreted the multiscale mechanics of lung ECM by means of FE-based simulations.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and lung decellularization

The study was carried out in lungs (n = 18) excised from healthy (~8 weeks old) adult Sprague-Dawley rats (~300 g) (Charles River, MA). The animal research protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation of the University of Barcelona following local and European regulations. Briefly, rats were anesthetized with urethane and sacrificed by exsanguination. Lungs were extracted en bloc with the heart, pulmonary artery and trachea.

Decellularization of the whole organ was performed by perfusion of decellularizing and washing media through the pulmonary artery and trachea simultaneously. First, lungs were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (ThermoFisher Scientific, MA) for 15 min followed by 10 min of deionized water to induce cell osmotic shock. Subsequently, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1% sodium dodecyl disulfate (SDS) (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) were perfused for 30 min and 2 h, respectively. Finally, lungs were perfused with deionized water for 15 min followed by 15 min of NaCl (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) solution and 15 min of PBS to obtain a decellularized lung. Acellular lungs for tensile assays (n = 9) were kept in PBS at 4 °C. Acellular lungs for AFM measurements (n = 9) were bronchially infused with tissue freezing medium (OCT compound, Sakura, CA) and frozen at −80 °C.

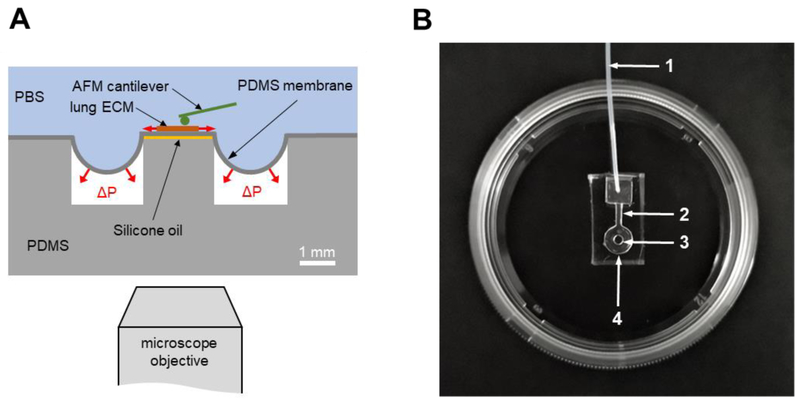

2.2. Chip design

The chip consisted of a PDMS well with a central pillar and covered with a thin PDMS membrane (Fig. 1). A lateral channel allowed the connection of the well to a servo-controlled vacuum pump. A thin layer of silicone oil between the pillar and the membrane avoided covalent bonding and minimized friction between both surfaces. The inlet of the well was connected to a vacuum servo-controlled pump (Parker Hannifin, OH) providing negative pressure underneath the membrane. The negative pressure produced a deflection of the membrane resulting in a uniform equi-biaxial strain in its central region covering the pillar. The strain in the membrane was set by controlling the applied vacuum pressure.

Fig. 1.

PDMS chip designed to measure ECM micromechanics with AFM under controlled stretch levels. (A) Schematic drawing of the chip consisting of a PDMS pillar at the center of a PDMS well. The well and the pillar are covered with an elastic PDMS membrane (~20 μm thick). A lung slice is adhered on top of the membrane covering the pillar. Vacuum (ΔP) applied underneath the membrane generates in-plane biaxial stretch at the central region of the membrane located above the pillar. Silicone oil placed between the pillar and the membrane avoids adhesion. The chip is covered by PBS. (B) Picture of a PDMS chip adhered to the bottom of a 35 mm culture dish. 1: vacuum inlet, 2: lateral channel, 3: pillar, 4: well.

2.3. Chip fabrication

Negative molds of the chip were produced with a conventional 3D printer (Ultimaker 2, The Netherlands). The molds were attached to a culture dish 100 mm in diameter and a 10:1 PDMS mixture of pre-polymer and curing agent (Sylgard 184 kit, Dow Corning, MI) was poured to a thickness of 5 mm. The PDMS was degassed for 1h in a bell jar vacuum desiccator (Kartell Labware, Italy) to avoid bubble formation and baked in an oven (Selecta, Spain) at 65 °C for 2h. After curing, blocks of PDMS were cut around the chip molds using a scalpel. The blocks were detached carefully from the culture dish using absolute ethanol to diminish the adhesion between the PDMS and the 3D printed mold.

The PDMS membrane was fabricated as described elsewhere [32]. Briefly, a 76 × 26 mm glass slide (Deltalab, UK) was cleaned by immersion and agitation in acetone, methanol, and isopropyl alcohol for 30 s sequentially, removing organic contaminants. The glass slide was activated with oxygen plasma treatment using a plasma cleaner (PDC-002, Harrick Scientific Products Inc., NY) (18 W for 30 s). Finally, the slide was treated with Repel Silane [(Tridecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyl) trichlorosilane] (ABCR GmbH & Co. KG, Germany) vapors in the vacuum desiccator for 1 h. A 10:1 PDMS degassed mixture was poured on the slide and spun (Laurell Technologies Corporation, PA) at 1000 RPM for 60 s to obtain a thickness of ~20 μm. After spinning, the slide was placed on the hot plate at 95 °C for 20 min to cure the PDMS.

To assemble the chip, first a thin layer of silicone oil was poured on top of the PDMS pillar with a 0.3 mm diameter syringe (Micro-Fine, BD, Spain). The surface of the PDMS block and the membrane was activated with plasma using a low-cost portable corona treater (Electro Technic Products, IL) at close proximity (~5 mm) for 1 min. The activated surface of the block was pressed against the activated side of the membrane and the edges were sealed with PDMS. The edges were then cut using a scalpel and the chip was carefully peeled off from the silanized glass slide. A 0.3 mm ID silicone tube was connected to the chip and sealed with PDMS. Finally, the chip was adhered to the bottom of a 35 mm culture dish with PDMS mixture placed around its edges and cured in the oven at 65 °C for 2 h. The stiffness of the membrane area located over the pillar was measured with AFM.

2.4. Measurement of macroscale mechanics by tensile stretching

A strip of ~7×2×2 mm was cut from the decellularized lung parenchyma with a scalpel, gently dried with tissue paper and its mass (M) measured with a precision scale. One end of the strip was fixed with cyanoacrylate glue to a hook attached to the lever arm of a servo-controlled displacement actuator (300C-LR, Aurora Scientific, Canada) which allowed us to stretch the strip and measure the stretched length (L) with a resolution of 1 μm. The other end of the strip was glued to a hook attached to a force transducer (404A, Aurora Scientific, Canada) to measure the force applied to the strip with a resolution of 2 μN. The unstretched strip length (L0) was defined as its length for a force of 0.1 mN.

The stretch ratio (λ) of a tissue strip subjected to a tensile force F is

| (1) |

where L is the length of the strip corresponding to F. The Lagrangian strain (ε) is computed as

| (2) |

The cross-sectional area in the undeformed state (A0) can be computed as

| (3) |

being ρ strip’s density (assumed to be 1.06 g/cm3). The Lagrangian tensile stress (σ) applied to the strip is

| (4) |

The macroscopic Young’s modulus is defined as the derivative of the σ-ε curve

| (5) |

Tensile tests were performed in PBS at room temperature (RT). To avoid history-dependent effects, lung strips were initially preconditioned by applying 10 cycles of triangular stretch at a frequency of 0.2 Hz and maximum strain of ~30%. After preconditioning, tissue strips were returned to the relaxed state followed by data collection from 10 more cycles. The first cycle was discarded, and the mean σ-ε; curve of the remaining 9 cycles was stored. The total duration of uniaxial tensile measurements was ~ 2 hours. EM was computed for each sample by fitting an exponential function to the mean σ-ε curve with a 0.05 strain window centered at the target strain and taking the derivative of the exponential fit.

2.5. Measurement of microscale mechanics by AFM

First, the membrane of the chips was treated with (3-Aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES, Sigma-Aldrich, MO) 10% in absolute ethanol (v/v) during 1 h at RT to facilitate the adhesion of the samples. Subsequently, the chips were washed with PBS for 15 min and treated with genipin 1.5% in PBS (v/v) for 30 min at RT. The genipin solution was removed and the chips were ready to use. Sections ~20 μm thick were cut using a cryostat from subpleural regions of the frozen decellularized lungs to exclude large airways. The slices were carefully manipulated with tweezers and placed on top of the region of membrane covering the pillar. Next, the chips were left overnight at 37 °C and 100% humidity to efficiently adhere the ECM slice to the chip membrane. Before measurements, the chips were washed with PBS for 10 min to eliminate OCT.

The inlet tube of the chip was connected to the servo-controlled vacuum pump and placed on top of the stage of an inverted optical microscope (Nikon TE-2000, Japan) with a custom-built AFM attached to it. Different negative pressures were applied to the chip to strain the ECM slice. Optical images were acquired with a CCD camera (Marlin F145B2, Allied Vision Technologies, Germany) at the different negative pressures to compute the actual ECM strain and to precisely place the AFM tip at the same ECM location in all subsequent measurements.

Lung ECM was probed in PBS at RT with Si3N4 V-shape Au-coated cantilevers with a nominal spring constant (k) of 0.03 N/m and a polystyrene sphere 4.5 μm in diameter attached at its end (Novascan Technologies, IA) and with similar cantilevers with a blunted four-sided regular pyramidal tip of 35° semi-included angle (θ) (MLCT-BIO, Bruker, CA). The cantilever was displaced in 3D with nanometer resolution by means of piezoactuators coupled to strain gauge sensors (Physik Instrumente, Germany) to measure the vertical displacement of the cantilever (z). The deflection of the cantilever (d) was measured with a quadrant photodiode (S4349, Hamamatsu, Japan). Before measurements, the slope of a deflection-displacement (d - z) curve obtained from a bare region of the culture dish was used to calibrate the relationship between the photodiode signal and cantilever deflection. A linear calibration curve with a sharp contact point was taken as indicative of a clean undamaged tip.

The force applied by the cantilever (F) was computed as:

| (6) |

and indentation depth was computed as:

| (7) |

where d0 is the deflection offset and z0 the cantilever displacement at the contact point between the tip and the sample. Force-displacement curves recorded with spherical tips were analyzed with the Hertz contact mechanical model for a sphere indenting a semi-infinite half-space:

| (8) |

where R is the sphere radius of the tip and v the Poisson’s ratio of the sample (assumed to be 0.5). Eq. 8 can be expressed in terms of z and d as:

| (9) |

Measurements obtained with pyramidal tips were fitted with the model of an ideal pyramid indenting a semi-infinite half-space:

| (10) |

Expressing Eq. 10 in terms of the measured variables:

| (11) |

The parameters of the model (Em, z0, and d0) were computed for each F - z curve by non-linear least-squares fitting using custom built code (MATLAB, The MathWorks Inc., MA). The fitting was performed to the approaching force curve up to a maximum indentation of ~0.7 μm. AFM measurements were performed at two different locations of each ECM sample and at different ECM strain levels. An image of the position of the tip in the ECM sample was acquired before each measurement. Each ECM sample was probed both with spherical and blunted pyramidal tips at strain levels ranging from 0 to ~30%. The total duration of the AFM measurements was ~2 hours. Using the recorded images, the ECM sample was repositioned after modifying the strain or changing the AFM tip to place the tip on the same measurement point of the sample. At each measurement point, Em was characterized as the average of the values computed from five F – z curves recorded consecutively with a ramp amplitude of 5 μm and frequency of 1 Hz (tip velocity of 10 μm/s). Micromechanics of the ECM sample was characterized for each strain level and AFM tip as the average of Em obtained at the two selected locations.

2.6. Constitutive law of the lung ECM

To analyze the correlation between micro- and macroscale ECM mechanics we developed a computational model for simulating the uniaxial loading response of the strip samples using the intrinsic mechanical properties of the acellular alveolar wall obtained from AFM measurements. We characterized the non-linear behavior of the alveolar tissue assuming a hyperelastic constitutive equation [33] characterized by a Yeoh law with the following strain energy density function

| (12) |

The first term in Eq. 12 corresponds to the isochoric (or distortional) elastic response and the second term to the volumetric (or dilational) elastic response. I1 is the first deviatoric strain invariant and Jel the elastic volume ratio. Cio and Di are material constants that characterize the isochoric and volumetric elastic response, respectively. We estimated the parameters of the Yeoh law from the AFM measurements obtained with both spherical and pyramidal tips using least squares fitting with FE software (Abaqus Dassault Systèmes, RI) in order to adjust numerical results to experimental measurements.

2.7. FE modelling of tip-sample contact micromechanics

Hertz contact models (Eq. 8 and 10) assume that the tip indents an elastic half-space under linear mechanical conditions. However, in our experimental measurements the tip indents a finite domain corresponding to the alveolar wall. Therefore, to assess the accuracy of the Young’s modulus computed using Eq. 8 and 10 we performed FE simulations (Abaqus Dassault Systèmes, RI) of the mechanics of the tip indenting the alveolar wall surface. Simulations were carried out with both spherical and pyramidal tips assuming a half-space and a finite domain with dimensions and nonlinear Yeoh mechanical properties that describe the behavior of the acellular alveolar wall slices (details of the FE-based simulations are described in Supplemental Information).

FE computations for the spherical tip were performed for a sphere of 4.5 μm diameter using hexahedral and tetrahedral elements. The semi-infinite half-space was simulated as the flat surface of a vertical cylinder of 200 μm radius (two order of magnitude wider than the tips) and 16.8 μm height. The finite domain was simulated as a cuboid with height of 16.8 μm, length of 400 μm and width of 6.6 μm. Given the complexity of modeling contact mechanics of non-axisymmetric indenters, pyramidal tips are commonly approximated by a cone which has the same Hertz equation than the pyramid with the exception than the 1/√2 factor in Eq. 10 is replaced by 2/π (11% difference) [34]. Therefore, for the simulation of the pyramidal tip indentation we performed computations for a conical tip of 35° semi-included angle and with blunted vertex (radius = 100 nm) indenting the same cylinder and cuboid as for the spherical tip. In both AFM probes, vertical displacements were imposed on the indenter and the vertical reaction force was obtained. Resulting F-δ curves were fitted (indentation depth of 0.7 μm) with the contact Hertz equations for spherical and conical tips to compute the apparent Young’s modulus.

2.8. FE modelling of macroscopic lung ECM mechanics

We simulated the 3D structure of the lung parenchymal strip as an homogeneous scaffold inducing a linear reduction of stiffness according to the equation

| (13) |

where t is the tissue fraction ratio (or equivalently, 1-porosity) and σ0 is the stress obtained in the simulation of the tensile test for the lung strip using the Yeoh model with 0% porosity. Since the porous of the decellularized lung parenchyma are filled with liquid, volume and porosity of the strips are assumed to be constant during stretching. Simulations were performed using a mesh consisting in 650 hexahedral elements. For the simulation of the uniaxial tension test by FE analysis we considered the dimensions of lung tissue strips (7 × 2 × 2 mm). To simulate the tensile test, two rigid plates were added, one at each end of the sample lung model. The deformation was applied as a Dirichlet condition. Therefore, one end of the sample was fixed, while the displacement was prescribed at the other end for each study case.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SE. Differences between means were analyzed with one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparison tests. Statistical tests were performed with SigmaPlot 13 (Systat Software Inc, CA). Values are considered significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. PDMS chip

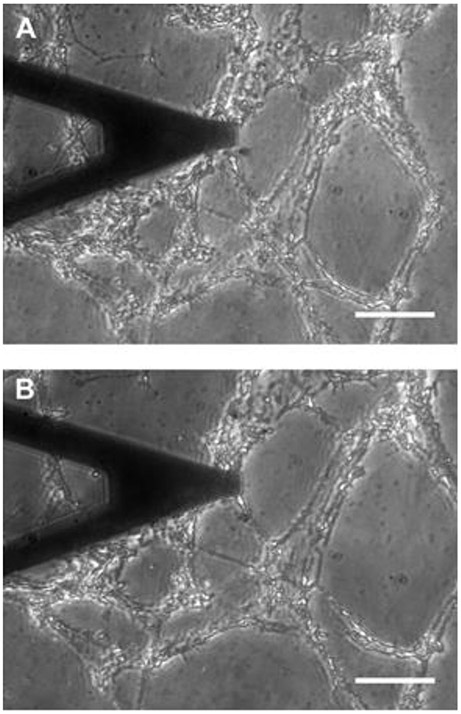

Figure 1 shows a PDMS chip produced with a pillar 2 mm in diameter centered in a well 6 mm in diameter covered with a ~20 μm thick PDMS membrane. The Young’s modulus of the PDMS membrane measured with the AFM above the pillar was > 3 MPa. An inlet tubbing (0.3 mm ID, 4 cm long) allowed connection to the vacuum source. Application of vacuum underneath the membrane resulted in 2D biaxial strain of the central region of the membrane located over the central pillar (Fig. 2). However, small variations in membrane thickness or 3D printing resulted in changes between chips in their membrane strain and vacuum pressure relationship. Therefore, the actual strain experienced by the ECM (Eq. 1 and 2) was computed as the relative change in distance between two points of the ECM images recorded before and after applying the pressure (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phase contrast image of a lung ECM slice (~20 μm thick) adhered to the membrane of a chip. (A) Unstretched state. (B) 19% strain. A V-shaped AFM cantilever is located over the ECM slice. Scale bar = 50 μm.

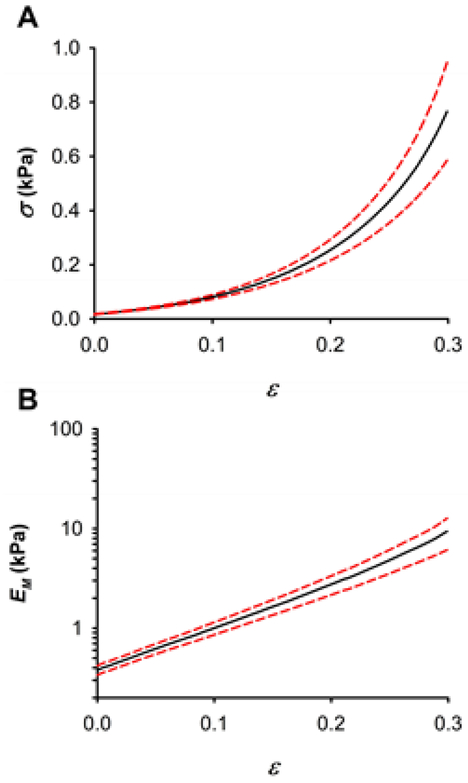

3.2. Macromechanics of lung ECM

Macroscopic stiffness of decellularized lung parenchymal strips was 0.38 ± 0.07 kPa at the unstretched state and exhibited a marked nonlinear elasticity with an approximate exponential relationship between stress and strain (Fig. 3). Inter-sample variability of macroscopic stiffness measurements was due to biological variability of rat lungs and to any variation in strip shape because they were cut with a scalpel. Macroscopic stiffness computed as the derivative of the stress-strain relationship also increased as a nearly exponentially function of strain. Therefore, the strain dependence of EM was well fitted by an exponential function (EM ~ eαε with a nonlinearity index α = 9.36 ± 0.99 (R2 = 0.992 ± 0.005).

Fig. 3.

Macromechanics of decellularized lung parenchymal strips probed by uniaxial tensile testing. (A) Stress-strain (σ-ε) relationship of lung ECM strips. (B) Dependence of the macroscopic Young’s modulus (EM) on strip strain. Data (n = 9) are shown as mean (black solid lines) ± SE (dashed red lines).

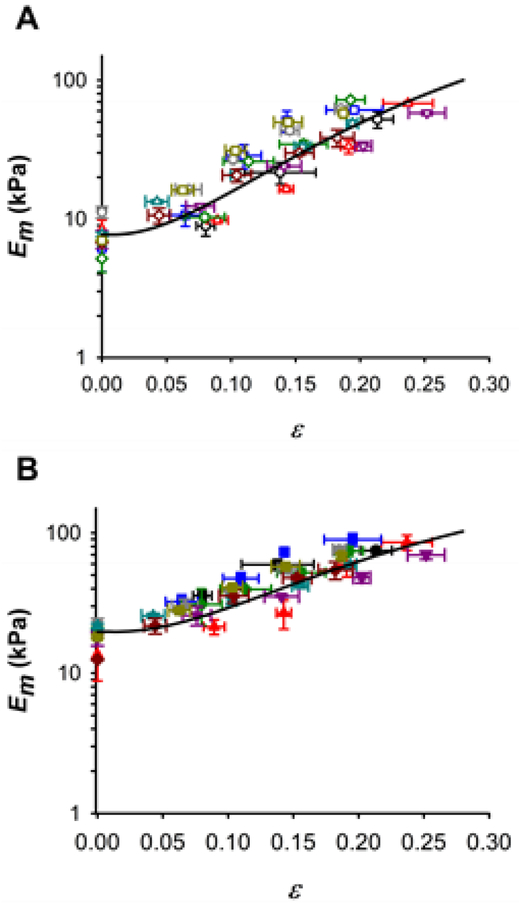

3.3. Micromechanics of lung ECM

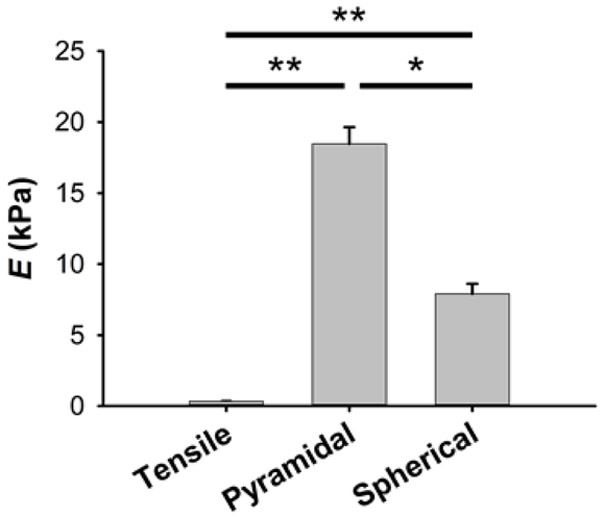

The PDMS allowed in-plane stretching of ECM lung slices by vacuum pressure (Fig. 2). The ECM slices used for AFM measurements had a height of 16.8 ± 0.2 μm. Alveoli walls had a thickness of 6.6 ± 0.7 μm. The effects of AFM tip shape and the small dimensions of the alveolar septum on AFM measurements were probed with both spherical blunted and pyramidal tips. Micromechanics of lung ECM measured by AFM with both probes revealed a highly nonlinear mechanical response to macroscopic tissue strain (Fig. 4). However, under unstretched conditions, pyramidal tips provided 2.3-fold higher values of Em than spherical tips (18.5 ± 1.2 kPa vs 7.9 ± 0.7 kPa, indentation depth = 0.7 μm) (Fig. 5). In addition to biological variability, intersample variability of AFM measurements could be due to the local heterogenous composition and structure of the ECM alveolar septa. It is noteworthy that Em was one order of magnitude higher than EM (Fig. 3-5). Stiffness measured with spherical tips exhibited a marked strain dependence increasing by ~6.5 times from the unstretched state to 20% strain (Fig. 4). Pyramidal tip Em measurements showed a weaker strain dependence with ~3.2-fold increase when the strip was subjected to 20% strain. The Yeoh constitutive equation (Eq. 12) fits the strain dependence with both tips well with parameters given in Table 1 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Nonlinear micromechanics of lung ECM measured by AFM. (A) Micromechanical Young’s modulus (Em) of decellularized lung parenchymal slices (n = 9) measured with a spherical tip (radius = 2.25 μm) at different strain (ε) levels. Symbols and colors identify different ECM slices (n = 9). (B) Em measurements performed with a pyramidal tip (semi-included angle = 35°, apex radius = 100 nm). Solid lines are a fit of the Yeoh model (Eq. 12). Data are mean ± SE (n = 9).

Fig. 5.

Multiscale stiffness of lung ECM. Young’s modulus of lung ECM at the unstretched state measured with macroscale tensile testing and with microscale AFM measurements using spherical and pyramidal tips (indentation depth of 0.7 μm). Data are mean ± SE (n = 9). * and ** are p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively.

Table 1.

Parameters of the Yeoh hyperelastic model (Eq. 12) of the acellular alveolar wall estimated by fitting AFM data obtained with spherical and pyramidal tips. Cio and Di are material constants that characterize the isochoric and volumetric elastic response, respectively.

| AFM tip | C10 | C20 | C30 | D1 | D2 | D3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kPa) | (kPa) | (kPa) | (kPa−1) | (kPa−1) | (kPa−1) | |

| Spherical | 1.3 | 8.9 | 26.2 | 0.009 | 0 | 0 |

| Pyramidal | 3.4 | 14.4 | 24 | 0.018 | 0 | 0 |

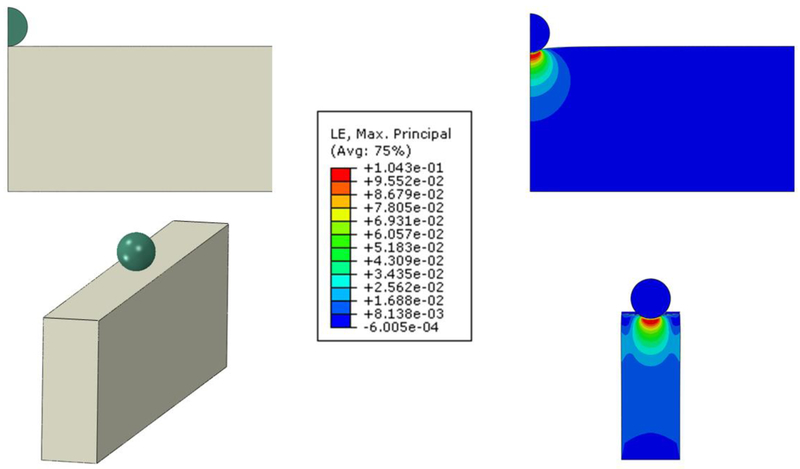

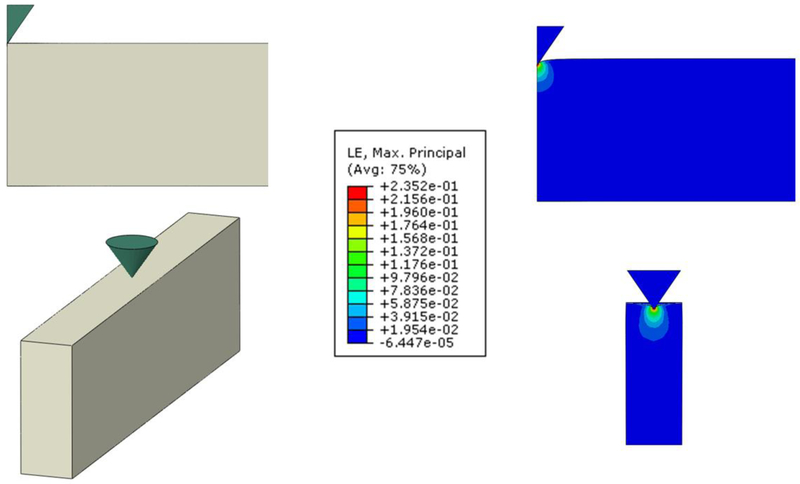

3.4. FE modelling of tip-sample contact mechanics

The effects of the nonlinear mechanical behavior of the ECM and the geometry and finite size of the sample on AFM measurements were analyzed by means of FE simulations of the indentation of a material with a stiffness of 7.7 kPa under unstretched conditions assuming the Yeoh hyperelastic equation defined with the spherical parameters in Table 1. Em computed for the spherical tip (diameter = 4.5 μm) indenting a semi-infinite half-space (cylinder with 200 μm radius) and an acellular alveolar wall model with an indentation depth of 0.7 μm was 10.4 kPa and 7.6 kPa, respectively (Fig. 6). Simulations with a blunted pyramidal tip (θ = 35°) gave Em of 27.0 kPa and 24.4 kPa for the half-space and the acellular alveolar wall model, respectively (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

FE simulations of a spherical tip (radius = 2.25 μm) indenting a Yeoh hyperelastic material of different dimensions. Strain distribution at indentation δ = 0.7 μm in the X-Y plane of a vertical cylinder 16.8 μm in height and 200 μm in radius (top, half-space model) and a cuboid with width = 6.6 μm, length = 400 μm and height = 16.8 μm (bottom, acellular alveolar wall model). Color scale is the common logarithmic maximal principal strain distribution (averaged at nodes). Maximum strain is 0.1 in both cases.

Fig. 7.

FE simulations of a blunted conical tip (semi-included angle = 35°, apex radius = 100 nm) indenting a Yeoh hyperelastic material of different dimensions. Strain distribution at indentation δ = 0.7 μm in the XY plane of a vertical cylinder 16.8 μm in height and 200 μm in radius (top, half-space model) and a cuboid with width = 6.6 μm, length = 400 μm and height = 16.8 μm (bottom, acellular alveolar wall model). Color scale is the common logarithmic maximal principal strain distribution (averaged at nodes). Maximum strain is 0.32 and 0.24 in the half-space and the acellular alveolar wall models, respectively.

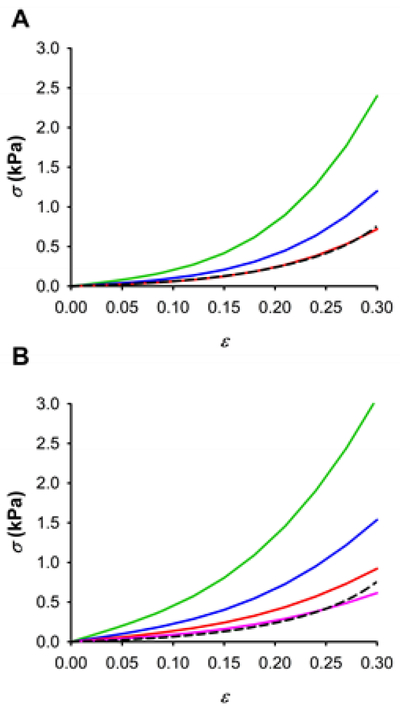

3.5. Multiscale FE modelling lung ECM mechanics

Fig 8 depicts fits of the porosity model (Eq. 13) to the average stress-strain relationship recorded with tensile testing (Fig. 3). FE simulations performed using nonlinear Em data measured with spherical tips provide an excellent fit of the stress-strain response of the decellularized lung strips for a tissue fraction ratio of 0.06. Pyramidal tip data also fits very well the macroscopic mechanical response of the acellular strip with a similar tissue fraction ratio (t = 0.04).

Fig. 8.

Porosity model of lung ECM. Fit of the Yeoh porous model to the macroscopic experimental stress-strain relationships (σ-ε) measured by tensile testing (dashed black line) for different material adjustments using spherical (A) and pyramidal (B) tip measurements at different levels of tissue fraction ratio: 0.2 (green), 0.1 (blue) and 0.06 (red), 0.04 (pink).

4. Discussion

In this work we designed and fabricated a new PDMS chip to characterize the micromechanical properties of thin tissue and ECM slices with AFM at controlled stretch levels. Using this unique experimental setup, our primary finding is a highly nonlinear mechanical behavior of rat decellularized lung slices at the level of single alveolar septal walls. The lung ECM exhibited a microscale Young’s modulus increasing with macroscopic tissue strain in accord with the constitutive Yeoh model. Macroscopic ECM stiffness probed with tensile loading also exhibited marked strain hardening. However, ECM was one order of magnitude softer at the macroscale than at the microscale. FE simulations indicated that the lower stiffness at the macroscale was due to the high porosity of the lung parenchyma.

Several devices have been developed to stretch cultured cells adhered to an elastic silicone membrane [35]. Although some of these devices can be coupled to AFM [36], they do not provide a rigid substrate which is a critical condition in Eq. 7 to accurately compute indentation. This is particularly important for probing samples much stiffer than cells such as tissues and ECM. An additional requirement for AFM mechanical measurements is to subject the sample to in-plane stretch perpendicular to the AFM indentation. Moreover, the stretching device should be compatible with optical microscopy. Therefore, we have designed a new PDMS chip compatible with AFM and optical microscopy based on a previously implemented cell stretching device (Fig. 1) [37, 38]. PDMS was chosen for chip fabrication due to its elasticity and optical transparency. Application of vacuum inside the well induced in-plane isotropic and equibiaxial strain at the central region of the membrane in contact with the central cylindrical post [38]. Moreover, since the lung ECM is much softer than the PDMS the acellular lung slice was subjected to the same deformation as the membrane. Since this region of the membrane slipped in contact with the pillar, the ECM sample was supported by a rigid PDMS substrate >40-fold stiffer than the ECM thereby allowing accurate computation of sample indentation (Eq.7). Controlling membrane strain with vacuum pressure facilitates a very simple operation of the chip. Although all the chips exhibited similar strain dependence on applied pressure, the actual magnitude of the linear strain produced in each chip depended on the variability in the fabrication process of the membrane. Therefore, we computed the actual strain in each ECM sample by recording optical images with the CCD of the microscope (Fig. 2) and measuring the change in the distance between 2 points located near the point of each AFM measurement. The dimensions of the well and the pillar were adjusted to maintain the image of the area of interest above the pillar within the field of view of the microscope for ECM stretching up to ~30%. Importantly, the small dimensions and simple operation of the chip (Fig. 1) allow its easy use in commercial AFM systems.

Young’s modulus measurements performed with AFM are commonly computed for indentations depth in the range of 0.5 – 1 μm. Therefore, we carried out AFM measurements and performed FE simulations for an indentation depth in the middle of this range (δ = 0.7 μm). The shape of the alveolar septa probed with AFM was a wall with a width of ~6 μm and a height of ~17 μm. Probing very thin samples with AFM could overestimate stiffness because of the rigid substrate. AFM measurements were computed with indentation depth more than one order of magnitude smaller than the height of the sample (16.8 ± 0.2 μm) which avoided substrate effects [39]. This is consistent with our FE simulations (Fig. 6 and 7) showing negligible strains at the bottom of the sample.

To assess the effect of sample nonlinearities and tip geometry on AFM measurements taken in the acellular alveolar wall, we probed each sample with both spherical and pyramidal tips. The blunted pyramidal tip resulted in ~3-fold Em larger values than the spherical tip. Interestingly, comparable results were previously reported in AFM measurements performed in cells and agarose gels [40]. To interpret this difference, we carried out FE simulations of the tip-contact mechanics. Em computed with the spherical tip at 0.7 μm indentation depth was 35% higher than the theoretical value for δ = 0 (7.7 kPa), reflecting the nonlinear response of the material caused by the large strains produced in the vicinity of the tip (Fig. 6). By contrast, the ~3-fold larger strains at the vertex of the pyramidal tip gave (Fig. 7) ~3-fold higher values of Em. On the other hand, the finite width of the sample resulted in 27% and 10% lower Em as compared with half-space computations when measured with the spherical and pyramidal tips, respectively. The diameter (D) of the contact area of a spherical tip indenting a flat surface can be estimated as D = 2(r∙δ)1/2 and D = 21/2∙δ∙tanθ for spherical and four-sided pyramidal tips, respectively [31]. At an indentation of δ = 0.7 μm the equivalent diameter of the contact area of a pyramidal tip is 0.7 μm which is one order of magnitude smaller than the width of the alveolar septa (Fig. 7). On the other hand, the contact diameter of a spherical tip 4.5 μm in diameter at δ = 0.7 μm is 2.25 μm which is closer to the width of the septa (Fig. 6). Therefore, the lower ratio between the diameter of the contact area and the width of the sample can account the smaller effect of the narrow width of the alveolar septum in pyramidal tip measurements.

The analytical expressions currently available for Hertzian contact stresses are applicable only for homogeneous materials. However, the acellular alveolar wall is a discrete structure with individual collagen fibers with a diameter in the range of 0.5 to 1.5 micron which is comparable to the contact size of the AFM tips. Therefore, the value of Em measured in each location depends on a variable contribution of the stiff fibers and soft proteoglycans in between. Consequently, alveolar tissue should be considered as a heterogeneous material, which could create perturbations in the elastic modulus estimations. To minimize the variability of our measurements, we characterized the stiffness of the acellular alveolar wall as the average of Em taken in two locations of several samples. We observed that the perturbations caused by heterogeneities are small, and their average corresponds to the homogenized value. These homogenized values of the elastic modulus provided enough data to determine a constitutive law allowing us to simulate the microscopic AFM measurements and the macroscopic tensile results mediated by lung porosity. Therefore, the average Em values we found with both tips reflect the apparent composite stiffness of the alveolar ECM. Our FE computations for a 4.5 μm spherical tip at δ = 0.7 μm indentation show that ECM nonlinearities could result in a slight overestimation (35%) of the Young’s modulus. However, this overestimation can be mostly counterbalanced by an underestimation of similar magnitude (27%) due to the finite size of the alveolar wall. Taken together, despite the limitations of our FE-simulations, our results show that the stiffness of the acellular alveolar septum can be measured with an error less than 10% using a spherical tip. On the other hand, pyramidal tips provide higher spatial resolution and are less affected by the narrow septum than spherical tips, but the higher local strains produced by the tip results in larger errors. Nevertheless, alveolar stiffness measured with blunted 35° pyramidal tips can be compared with spherical tips by multiplying with a factor of 2.5. It should be noted that recent AFM measurements performed in non-decellularized slices of pulmonary arterial tissue reported stiffness one order of magnitude higher with acute pyramidal tips (half-angle of 18°) than with spherical tips [41]. A similar difference was reported in AFM measurements performed in cultured cells with spherical and acute pyramidal tips [42]. This much larger differences between spherical and pyramidal tips could be attributed to the higher local strains produced by very sharp tips.

The lung ECM scaffolds were obtained by decellularization of fresh excised lungs. The decellularization protocol used in this study has been previously developed and eliminates cell materials of the lung tissue preserving the composition and 3D structure of the ECM [12, 27, 29]. Lung ECM slices with a thickness of ~20 μm cut with a cryostat provided a clear image of the alveolar structure with optical microscopy (Fig. 2) and allowed AFM measurements of the intrinsic mechanical properties of the acellular alveolar wall. As previously shown, freezing/thawing has minor effects in the mechanical properties of decellularized lung tissue [43]. We measured acellular lung stiffness at RT. Nevertheless, little differences should be expected at 37°C since negligible changes in lung tissue stiffness has been observed between 25°C and 37°C with flat plate rheology [44]. We adhered the acellular lung slices to the surface of the PDMS membrane functionalized with genipin, which is a naturally occurring organic crosslinker that reacts with primary amines of ECM biopolymers [45]. Genipin provided a firm adhesion of the ECM slice to the PDMS membrane up to the maximum stretch of our experiments (~30%). The lung parenchyma is an interconnected 3D structure with a tendency to collapse which is stabilized by the internal stress (prestress) of the matrix generated by the action of external forces [46]. The level of prestress controls lung ECM mechanics resulting in a marked volume dependence of tissue stiffness. It should be noted that we performed the tensile tests in liquid-filled decellularized lung strips lacking air-liquid interfacial surface forces that also tend to collapse the alveoli [47]. Therefore, the stiffness of the air-filled native lung is determined by both the elastic forces of the lung ECM and the surface forces within the alveoli. During normal breathing lung tissues are subjected to strain levels in the order of 10-20% [47-50]. Consequently, we have studied nonlinear ECM mechanics in the physiological strain range. However, since the acellular lung slice was adhered to the deformable membrane, the alveolar septa were subjected to 2D uniform strain. On the other hand, 3D inflation of the air-filled native lung can result in partial folding-unfolding of the alveolar septa at low volumes [47] which makes difficult to accurately relate the 2D strain values of our measurements to 3D volume changes in the native lung.

Tensile tests performed in decellularized strips measure macroscale stiffness of the bulk ECM including the contribution of the intrinsic micromechanical properties of the acellular alveolar wall as well as the 3D network architecture of the alveoli. Macroscopic stiffness of lung ECM strips exhibits exponential strain stiffening behavior similar to that reported in fresh lung tissue strips [21, 23]. Consistently with the dominant contribution of the connective tissue network in lung parenchymal mechanics [28], the magnitude of the stress-strain we found in rat lung ECM strips is comparable to that reported in fresh lung parenchymal strips [21, 23].

In the unstretched state, the values of Em we obtained with a blunted pyramidal tip (Fig. 4) are similar to those found in previous studies carried out in unstretched samples of decellularized alveolar septa [27, 29]. Noteworthy, previous AFM measurements performed in different regions of unstretched decellularized lungs showed no differences between alveolar septa and alveolar junctions, but the pleura and the wall of the vessels exhibited 2 to 3-fold higher stiffness than the alveoli [29]. Differences in stiffness could also be expected between the alveolar septa and the entrance rigs of the alveoli which exhibit a higher density of collagen and elastin fibrils [51]. Interestingly, an elastic modulus comparable with that we found in ECM strips with tensile testing has been reported in lung tissue slices 400 μm in thickness probed with AFM under unstretched conditions [52]. Therefore, stiffness measurements performed in thick slices with AFM are also determined in a large part by the 3D network architecture of the lung parenchyma. Since in our case the stiffness strongly varies with the local strain on the alveolar septal wall (Fig. 4), it is important to relate the local strain to the macroscopic global strain. Using a computational model, the local strain was estimated to vary linearly with and be ~28% smaller than the global strain [53]. Accordingly, our AFM-based intrinsic wall stiffness is approximately an order of magnitude higher than macroscopic stiffness of the tissue strip. This is due to the porous nature of the alveolar architecture allowing gradual alignment of the walls during tissue stretch and hence resulting in the lower wall strain. This multiscale phenomenon bridges the scales between the elasticity of a single wall and that of a large network of walls within the tissue strip. Indeed, using a model analysis that accounts for such alignment which also takes into account of the elasticity of proteoglycans, a 10-fold difference was estimated in wall and tissue strip stiffnesses [23]. However, our study represents the first direct multiscale measurements of tissue elasticity.

To interpret this difference between single wall and tissue level elasticity, we used a simple model of the lung parenchyma modeled as a homogeneous and isotropic porous nonlinear medium. By means of FE simulations, we show that macroscale stiffness can be estimated from acellular alveolar wall stiffness assuming a tissue fraction ratio of ~0.05. A small tissue fraction ratio is consistent with the highly porous architecture of the lung ECM (Fig. 2). A tissue fraction ratio of 0.17 has been measured in nondecellularized samples of human lung obtained from autopsy using 3D micro-CT imaging [54]. Differences in tissue fraction ratio estimations might be due to differences in the lung architecture between human and rat, changes in sample preparation, and differences between 2D and 3D assessment of tissue fraction ratio.

AFM has been used to measure ECM stiffness of several tissues including lung and heart under unstretched conditions [27, 55]. The new PDMS chip combined with AFM allowed us to reveal the nonlinear micromechanical properties of the ECM isolated from any contribution of the 3D network architecture. Cells are anchored to their microenvironment through microscale focal adhesions which are adhesive complexes that connect the cells’ cytoskeleton to the ECM [56]. Lung cells sense the mechanical properties of their microenvironment by applying contact forces through focal adhesions which generate microscale deformations in the surrounding microenvironment [57]. The AFM also probes the sample by applying microscale deformations, thus providing stiffness measurements at the scale that cells probe. Therefore, our measurements with AFM and tensile testing demonstrate that alveolar cells sense a microenvironment one order of magnitude stiffer than that of the whole lung tissue. Lung tissues are continuously subjected to strain changes during breathing. Therefore, given the exponential nonlinear behavior the lung tissues, breathing results in marked changes in the ECM stiffness sensed by alveolar cells providing tissue-specific mechanical signals to the cells. It is important to realize that studies on the effect of microscale stiffness on cell behavior have been commonly carried out by seeding cells on synthetic substrates with stiffness values mimicking those obtained from macroscopic measurements. Earlier AFM studies were performed in unstretched samples, a setting that does not encompass the physiological conditions for lungs or other tissues subjected to stretch.

5. Conclusions

Here we studied the nonlinear mechanical behavior of lung ECM using a multiscale approach. Knowledge of ECM nonlinear mechanics at the macroscale is clinically relevant since it is the main determinant of the global mechanical behavior of the lungs including breathing and ventilation distribution and its alteration is associated with major pulmonary diseases. On the other hand, knowledge of nonlinear micromechanics is of paramount importance to improve our current understanding of cell-matrix interactions. Our results reveal that the stiffness of the alveolar cell microenvironment is governed by the global strain of the lung scaffold. Importantly, stiffness of the acellular alveolar septa is one order of magnitude higher than that of the lung tissue. FE simulations indicate that this difference is mostly due to the highly porous structure of lung tissue. The marked nonlinear stiffness of the lung ECM measured at the microscale indicates that under physiological conditions lung cells are surrounded by a microenvironment stiffer than in the relaxed tissue. Furthermore, changes in tissue strain during breathing result in variations in ECM stiffness which provide tissue-specific mechanical signals to lung cells. The results we report here on the modulation of local stiffness by lung stretch, with relevance for biological cell-ECM crosstalk, could be translated to other tissues (e.g. heath, arteries, bladder, gut, tendons) which are physiologically also exposed to stretch.

Supplementary Material

Statement of significance.

The micromechanical properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM) are a major determinant of cell behavior. The ECM is exposed to mechanical stretching in the lung and other organs during physiological function. Therefore, a thorough knowledge of the nonlinear micromechanical properties of the ECM at the length scale that cells probe is required to advance our understanding of cell-matrix interplay. We designed a novel PDMS chip to perform atomic force microscopy measurements of ECM micromechanics on decellularized rat lung slices at different macroscopic strain levels. For the first time, our results reveal that the microscale stiffness of lung ECM markedly increases with macroscopic tissue strain. Therefore, changes in tissue strain during breathing result in variations in ECM stiffness providing tissue-specific mechanical signals to lung cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mr. Miguel A. Rodríguez for their excellent technical assistance. This work was supported in part by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (FIS-PI14/00280, SAF2017-85574-R, DPI2017-83721-P, DPI2015-64221-C2-1-R, BFU2017-90692-REDT, AEI/FEDER-UE), Generalitat de Catalunya (CERCA Program), and National Institutes of Health (U01-HL-139466).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Badylak SF, Freytes DO, Gilbert TW, Extracellular matrix as a biological scaffold material: Structure and function, Acta Biomater. 5(1) (2009) 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Suki B, Ito S, Stamenovic D, Lutchen KR, Ingenito EP, Biomechanics of the lung parenchyma: critical roles of collagen and mechanical forces, J. Appl. Physiol 98 (2005) 1892–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Suki B, Stamenovic D, Hubmayr RD, Lung Parenchymal Mechanics, Compr Physiol 1 (2011) 1317–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Discher DE, Smith L, Cho S, Colasurdo M, Garcia AJ, Safran S, Matrix Mechanosensing: From Scaling Concepts in 'Omics Data to Mechanisms in the Nucleus, Regeneration, and Cancer, Annual review of biophysics 46 (2017) 295–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Engler AJ, Carag-Krieger C, Johnson CP, Raab M, Tang HY, Speicher DW, Sanger JW, Sanger JM, Discher DE, Embryonic cardiomyocytes beat best on a matrix with heart-like elasticity: scar-like rigidity inhibits beating, J. Cell Sci 121 (2008) 3794–3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sunyer R, Conte V, Escribano J, Elosegui-Artola A, Labernadie A, Valon L, Navajas D, García-Aznar JM, Muñoz JJ, Roca-Cusachs P, Trepat X, Collective cell durotaxis emerges from long-range intercellular force transmission, Science 353(6304) (2016) 1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Klein EA, Yin L, Kothapalli D, Castagnino P, Byfield FJ, Xu T, Levental I, Hawthorne E, Janmey PA, Assoian RK, Cell-Cycle Control by Physiological Matrix Elasticity and In Vivo Tissue Stiffening, Curr. Biol 19(18) (2009) 1511–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mathur A, Moore SW, Sheetz MP, Hone J, The role of feature curvature in contact guidance, Acta Biomater. 8(7) (2012) 2595–2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Elosegui-Artola A, Andreu I, Beedle AEM, Lezamiz A, Uroz M, Kosmalska AJ, Oria R, Kechagia JZ, Rico-Lastres P, Le Roux AL, Shanahan CM, Trepat X, Navajas D, Garcia-Manyes S, Roca-Cusachs P, Force Triggers YAP Nuclear Entry by Regulating Transport across Nuclear Pores, Cell 171(6) (2017) 1397–1410.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Suki B, Bates JHT, Extracellular matrix mechanics in lung parenchymal diseases, Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol 163 (2008) 33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhou Y, Horowitz JC, Naba A, Ambalavanan N, Atabai K, Balestrini J, Bitterman PB, Corley RA, Ding B-S, Engler AJ, Hansen KC, Hagood JS, Kheradmand F, Lin QS, Neptune E, Niklason L, Ortiz LA, Parks WC, Tschumperlin DJ, White ES, Chapman HA, Thannickal VJ, Extracellular matrix in lung development, homeostasis and disease, Matrix Biol. (2018) 77–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Melo E, Cardenes N, Garreta E, Luque T, Rojas M, Navajas D, Farre R, Inhomogeneity of local stiffness in the extracellular matrix scaffold of fibrotic mouse lungs, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 37 (2014) 186–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ebihara T, Venkatesan N, Tanaka R, Ludwig MS, Changes in Extracellular Matrix and Tissue Viscoelasticity in Bleomycin–induced Lung Fibrosis, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 162(4) (2000) 1569–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kononov S, Brewer K, Sakai H, Cavalcante FSA, Sabayanagam CR, Ingenito EP, Suki B, Roles of Mechanical Forces and Collagen Failure in the Development of Elastase-induced Emphysema, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 164(10) (2001) 1920–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ito S, Bartolák-Suki E, Shipley JM, Parameswaran H, Majumdar A, Suki B, Early Emphysema in the Tight Skin and Pallid Mice: Roles of Microfibril-Associated Glycoproteins, Collagen, and Mechanical Forces, Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol 34(6) (2006) 688–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Puig M, Lugo R, Gabasa M, Giménez A, Velásquez A, Galgoczy R, Ramírez J, Gómez-Caro A, Busnadiego Ó, Rodríguez-Pascual F, Gascón P, Reguart N, Alcaraz J, Matrix Stiffening and β1 Integrin Drive Subtype-Specific Fibroblast Accumulation in Lung Cancer, Mol. Cancer Res 13(1) (2015) 161–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Miyazawa A, Ito S, Asano S, Tanaka I, Sato M, Kondo M, Hasegawa Y, Regulation of PD-L1 expression by matrix stiffness in lung cancer cells, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 495(3) (2018) 2344–2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tilghman RW, Cowan CR, Mih JD, Koryakina Y, Gioeli D, Slack-Davis JK, Blackman BR, Tschumperlin DJ, Parsons JT, Matrix Rigidity Regulates Cancer Cell Growth and Cellular Phenotype, PLoS One 5(9) (2010) e12905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jeong J, Keum S, Kim D, You E, Ko P, Lee J, Kim J, Kim JW, Rhee S, Spindle pole body component 25 homolog expressed by ECM stiffening is required for lung cancer cell proliferation, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 500(4) (2018) 937–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Navab R, Strumpf D, To C, Pasko E, Kim KS, Park CJ, Hai J, Liu J, Jonkman J, Barczyk M, Bandarchi B, Wang YH, Venkat K, Ibrahimov E, Pham NA, Ng C, Radulovich N, Zhu CQ, Pintilie M, Wang D, Lu A, Jurisica I, Walker GC, Gullberg D, Tsao MS, Integrin alpha11beta1 regulates cancer stromal stiffness and promotes tumorigenicity and metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer, Oncogene 35(15) (2016) 1899–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Navajas D, Maksym GN, Bates JHT, Dynamic viscoelastic nonlinearity of lung parenchymal tissue, J. Appl. Physiol 79(1) (1995) 348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yuan H, Kononov S, Cavalcante FSA, Lutchen KR, Ingenito EP, Suki B, Effects of collagenase and elastase on the mechanical properties of lung tissue strips, J. Appl. Physiol 89(1) (2000) 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cavalcante FSA, Ito S, Brewer K, Sakai H, Alencar AM, Almeida MP, Andrade JS, Majumdar A, Ingenito EP, Suki B, Mechanical interactions between collagen and proteoglycans: implications for the stability of lung tissue, J. Appl. Physiol 98 (2005) 672–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sugihara T, Martin CJ, Hildebrandt J, Length-tension properties of alveolar wall in man, J. Appl. Physiol 30(6) (1971) 874–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Vawter DL, Fung YC, West JB, Elasticity of excised dog lung parenchyma, J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 45(2) (1978) 261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Alcaraz J, Buscemi L, Grabulosa M, Trepat X, Fabry B, Farre R, Navajas D, Microrheology of human lung epithelial cells measured by atomic force microscopy, Biophys. J. 84 (2003) 2071–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Luque T, Melo E, Garreta E, Cortiella J, Nichols J, Farre R, Navajas D, Local micromechanical properties of decellularized lung scaffolds measured with atomic force microscopy, Acta Biomater. 9(6) (2013)6852–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yuan H, Ingenito EP, Suki B, Dynamic properties of lung parenchyma: mechanical contributions of fiber network and interstitial cells, J. Appl. Physiol 83 (1997) 1420–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Melo E, Garreta E, Luque T, Cortiella J, Nichols J, Navajas D, Farre R, Effects of the Decellularization Method on the Local Stiffness of Acellular Lungs, Tissue Eng. Part C-Methods 20(5) (2014) 412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nonaka PN, Uriarte JJ, Campillo N, Melo E, Navajas D, Farre R, Oliveira LVF, Mechanical properties of mouse lungs along organ decellularization by sodium dodecyl sulfate, Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol 200 (2014) 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jorba I, Uriarte JJ, Campillo N, Farre R, Navajas D, Probing Micromechanical Properties of the Extracellular Matrix of Soft Tissues by Atomic Force Microscopy, J. Cell. Physiol 232(1) (2017) 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Campillo N, Jorba I, Schaedel L, Casals B, Gozal D, Farre R, Almendros I, Navajas D, A Novel Chip for Cyclic Stretch and Intermittent Hypoxia Cell Exposures Mimicking Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Front. Physiol 7 (2016) 319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rausch SMK, Martin C, Bornemann PB, Uhlig S, Wall WA, Material model of lung parenchyma based on living precision-cut lung slice testing, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 4(4) (2011) 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Radmacher M, Measuring the elastic properties of living cells by the atomic force microscope, in: Bhanu HJKH Jena P (Ed.), Methods Cell Biol., Academic Press; 2002, pp. 67–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Waters CM, Roan E, Navajas D, Mechanobiology in Lung Epithelial Cells: Measurements, Perturbations, and Responses, Compr. Physiol 2(1) (2012) 1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Rápalo G, Herwig JD, Hewitt R, Wilhelm KR, Waters CM, Roan E, Live Cell Imaging during Mechanical Stretch, JoVE (102) (2015) e52737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Trepat X, Deng LH, An SS, Navajas D, Tschumperlin DJ, Gerthoffer WT, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ, Universal physical responses to stretch in the living cell, Nature 447(7144) (2007) 592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Trepat X, Grabulosa M, Puig F, Maksym GN, Navajas D, Farre R, Viscoelasticity of human alveolar epithelial cells subjected to stretch, Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol 287 (2004) L1025–L1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gavara N, Chadwick RS, Determination of the elastic moduli of thin samples and adherent cells using conical atomic force microscope tips, Nat Nano 7 (2012) 733–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Rico F, Roca-Cusachs P, Gavara N, Farre R, Rotger M, Navajas D, Probing mechanical properties of living cells by atomic force microscopy with blunted pyramidal cantilever tips, Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys 72(2 Pt 1) (2005) 021914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sicard D, Fredenburgh LE, Tschumperlin DJ, Measured pulmonary arterial tissue stiffness is highly sensitive to AFM indenter dimensions, J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 74 (2017) 118–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wu P-H, Aroush DR-B, Asnacios A, Chen W-C, Dokukin ME, Doss BL, Durand-Smet P, Ekpenyong A, Guck J, Guz NV, Janmey PA, Lee JSH, Moore NM, Ott A, Poh Y-C, Ros R, Sander M, Sokolov I, Staunton JR, Wang N, Whyte G, Wirtz D, A comparison of methods to assess cell mechanical properties, Nat. Methods 15(7) (2018) 491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Nonaka PN, Campillo N, Uriarte JJ, Garreta E, Melo E, de Oliveira LVF, Navajas D, Farre R, Effects of freezing/thawing on the mechanical properties of decellularized lungs, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 102(2) (2014) 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Polio SR, Kundu AN, Dougan CE, Birch NP, Aurian-Blajeni DE, Schiffman JD, Crosby AJ, Peyton SR, Cross-platform mechanical characterization of lung tissue, PLoS One 13(10) (2018) e0204765–e0204765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Genchi GG, Ciofani G, Liakos I, Ricotti L, Ceseracciu L, Athanassiou A, Mazzolai B, Menciassi A, Mattoli V, Bio/non-bio interfaces: A straightforward method for obtaining long term PDMS/muscle cell biohybrid constructs, Colloids Surf. B. Biointerfaces 105 (2013) 144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Stamenovic D, Micromechanical foundations of pulmonary elasticity, Physiol. Rev 70(4) (1990) 1117–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Roan E, Waters CM, What do we know about mechanical strain in lung alveoli?, Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 301 (2011) L625–L635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Perlman CEWY, In situ determination of alveolar septal strain, stress and effective Young’s modulus: an experimental/computational approach, Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol 307(4) (2014) L302–L310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Perlman CE, Bhattacharya J, Alveolar expansion imaged by optical sectioning microscopy, J. Appl. Physiol 103 (2007) 1037–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Tschumperlin DJ, Margulies SS, Alveolar epithelial surface area-volume relationship in isolated rat lungs, J. Appl. Physiol 86 (1999) 2026–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mercer RR, Crapo JD, Spatial distribution of collagen and elastin fibers in the lungs, J. Appl. Physiol 69 (1990) 756–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Liu F, Mih JD, Shea BS, Kho AT, Sharif AS, Tager AM, Tschumperlin DJ, Feedback amplification of fibrosis through matrix stiffening and COX-2 suppression, J. Cell Biol 190 (2010) 693–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Jesudason R, Sato S, Parameswaran H, Araujo AD, Majumdar A, Allen PG, Bartolák-Suki E, Suki B, Mechanical Forces Regulate Elastase Activity and Binding Site Availability in Lung Elastin, Biophys. J 99(9) (2010) 3076–3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kampschulte M, Schneider CR, Litzlbauer HD, Tscholl D, Schneider C, Zeiner C, Krombach GA, Ritman EL, Bohle RM, Langheinrich AC, Quantitative 3D Micro-CT Imaging of Human Lung Tissue, Fortschr Röntgenstr 185(09) (2013) 869–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Perea-Gil I, Uriarte JJ, Prat-Vidal C, Galvez-Monton C, Roura S, Llucia-Valldeperas A, Soler-Botija C, Farre R, Navajas D, Bayes-Genis A, In vitro comparative study of two decellularization protocols in search of an optimal myocardial scaffold for recellularization, Am J Transl Res 7 (2015) 558–573. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kim D-H, Wirtz D, Focal adhesion size uniquely predicts cell migration, The FASEB Journal 27(4) (2013)1351–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Gavara N, Sunyer R, Roca-Cusachs P, Farre R, Rotger M, Navajas D, Thrombin-induced contraction in alveolar epithelial cells probed by traction microscopy, J. Appl. Physiol 101(2) (2006) 512–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.