In the pharmaceutical field, liquid-handling robots are routinely used and have brought new opportunities for high throughput assays, especially for drug screening and for the production of DNA and small molecule microarrays [1, 2]. Cell culture microplates are also commonly used to screen cellular behaviors. Automates that produce biomaterials at a high throughput to study cellular responses in a combinatorial manner are only beginning to emerge [3–6]. The most common methods are printing and ink-jet machines [3, 6] to produce platforms made of synthetic polymers [7, 8] or extracellular matrix proteins [9]. Using a nanoliter liquid-dispensing robot, pioneering work by the Lutolf group showed that it is possible to encapsulate mouse embryonic stem cells in 3D engineered hydrogels made of polyethyleneglycol (PEG) inside multiple-well culture plates [10] in order to probe simultaneously the roles of matrix elasticity, proteolytic degradability and of different signaling proteins on cell fate [10]. 2D polymeric surface coatings are interesting for high content cell screening in tissue engineering and biotechnologies [11], since cellular processes are always initiated by cellular interactions with a material surface. To date, however, the bottom of the microwells is mostly made of polystyrene or glass, at best treated with ECM proteins (fibronectin, collagen, laminin), with a mixture of these such as Matrigel [12], with polypeptides such as poly(L-lysine) or an active peptide [13] to render them more biomimetic. However, it is now recognized that substrate stiffness and biochemical signals are both important in guiding stem cell adhesion and fate [14, 15]. Synthetic gels of control stiffness, such as Matrigen ® have recently become commercially available in multiple-well plate format. However, their thickness in the range 200 to 500 μm currently limits their high resolution imaging and compatibility with biological assay [16].

In the past years, the LbL assembly technique [17] has emerged as a promising tool for biomedical applications [18–20] in view of its versatility, notably the wide range of building blocks, assembly conditions, and the possibility to locally deliver bioactive molecules. The panel of already-available technologies to assemble LbL films is impressive [21]. Indeed, automated deposition of LbL is already well established on centimeter-scale substrates using dip-coating [22, 23], spraying [24, 25] and spin-coating [26], but these technologies are not well suited for applications in biotechnology using expensive biomolecules since they require a significant volume of liquid (mL range) and cannot be adapted to cell culture microplates. Microfluidics using custom-made devices were recently applied to design combinatorial LbL coatings to perform biological assays for screening of cellular behaviors on film-thickness gradients [27] or to build a variety of LbL films [28]. To our knowledge, the potential of commercially-available liquid handling robots that are widely used in biotechnology has never been exploited for the in situ buildup and analysis of LbL films in microplates. Only one study uses such a robot to deposit synthetic LbL films on bottomless silicon substrates for ex-situ analysis [29]. However, such a procedure is not compatible with the fully automated acquisition and characterization of LbL coatings and cellular behaviors.

Here, our aim was to establish the potential of layer-by-layer (LbL) films as biomimetic surface coatings of microwells. To the end, we optimized an automated liquid handling robot to directly deposit LbL films in multiple-well cell culture plates to assay cellular behavior at high throughput. By taking advantage of the optical transparency of LbL films and the adaptability of microplates to common optical microscopes and microplate readers, we automatized the in situ buildup of LbL films in microwells, 3D imaging of the films and the quantitative analysis of cellular adhesion and differentiation.

We selected the 96-well plate format, particularly interesting for cell screening assays on biomimetic coatings since multiple conditions can be screened in parallel and the number of cells per well is small, typically < 2000. We demonstrate that this method can be used for different types of LbL films over a wide range of film thicknesses, from a few tens of nanometers to a few micrometers. We further use it for testing the bioactivity of films, assessed here by cell adhesion on a peptide-grafted polyelectrolyte and by stem cell differentiation on osteoinductive LbL films. The implementation of such a process on commercially available liquid handling robots will undoubtedly broaden the range of possibilities offered by the well-controlled LbL coatings in view of future applications in biomolecular and cellular screening for biotechnologies and regenerative medicine.

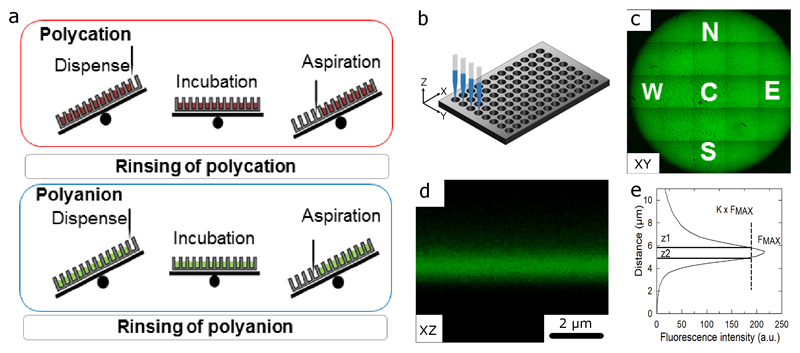

We used a robotic arm equipped with multiple channels to reproducibly deposit layer-by-layer films inside microwells of the same microplate and between microwells of different microplates (Figure 1). We reasoned that controlling liquid homogeneity inside each microwell would impact the homogeneity of film built at the bottom of the microwell. To this end, we introduced the tilting (T) of the microplate carrier during dispensing and aspiration steps of the polyelectrolytes and rinsing solutions (Figure 1a). In addition, to ensure homogeneous removal of the liquid from the microplate during the aspiration step, we aspirated an excess volume back. This excess volume, expressed in % of the initially dispensed volume, was set to 10%. Using the automated liquid handling robot, it is possible to position the tips in X, Y and Z directions (Figure 1b) to dispense and aspirate the liquids in multiple wells using the multi-channel arm. To assess the spatial homogeneity of the film inside each ~6-mm diameter microwell, we automated the imaging of each microwell using a confocal microscope (Figure 1c). 5 representative positions were chosen in each microwell: the Center (C) and 4 pole positions (North, East, South, West, respectively noted N, E, S, W). We chose (PLL/HA) films as a model system of well-characterized exponentially growing films [30]. At each position, Z-stacks of the fluorescently labeled film with PLLFITC were acquired (Figure 1d). Thanks to PLLFITC diffusion inside the film [30], film thickness (h) was automatically calculated from the fluorescence intensity profile through the film using a custom-made Image J macro (see Material and methods) (Figure 1e).

Figure 1. Schematic of the layer-by-layer deposition at high throughput in multiple well cell culture microplates and principle of the film thickness measurement using confocal microscopy.

(a) The automated process for the polycation and polyanion deposition consists of dispensing and aspiration steps: when tilting is used, the microplate is tilted during all dispensing and aspiration steps (b) Definition of the (X,Y,Z) coordinates in a multiple well microplate; for commercially-available microplates, the (X,Y) coordinates of each microwell center are known. Z0, the initial position of the tip during the solution dispensing, needs to be first defined by the user; (c) Imaging an entire microwell (diameter of 6.4 mm) using the tile scan option and a 10X objective (zoom x0.5) from 5x5 neighboring but non-overlapping fields. Tile scan provides information on the global homogeneity of the film in a specific microwell. Definition the center position C and 4 pole positions (N, W, E, S) where film thickness h is measured automatically after acquiring Z-stacks at high resolution. (d) High resolution transverse sections (X,Z) using 63X objective were automatically acquired for each single position. (e) For each cross-section, the automatized measurement of film thickness h was made by plotting the fluorescence intensity profile, finding its maximum intensity (Fmax) (FMax), applying a proportionality factor K, and automated calculation of h=Z1-Z2 using a custom-made macro in Image J (see Materials/Methods section).

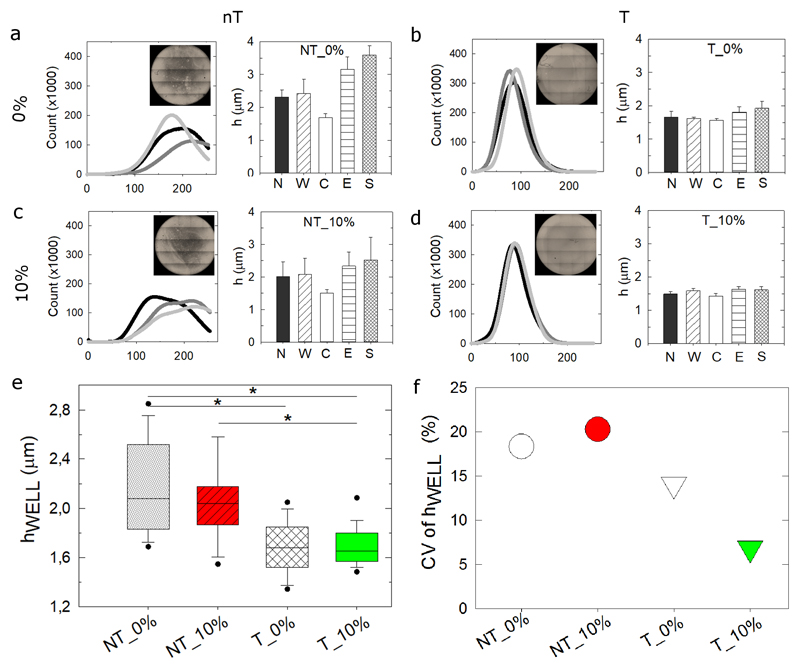

Having the possibility to tilt the microplate and to aspirate an excess volume, we decided to compare four experimental conditions (Figure 2): microplates not tilted (nT) or tilted (T) in the absence or presence of an excess aspiration volume of 10%, named hereafter: nT_0%; nT_10%; T_0%; T_10%. The global film homogeneity was quantitatively assessed by plotting the fluorescence intensity profiles of all the pixels of an entire microwell (Figure 2a, inset images) as well as by comparing hC, hN, hE, hS, hW for a large number of microwells (Figure 2a-d and Figure S1). These profiles were pooled from internal replicates in a single experiment and inter-experiment replicates. The coefficient of variation (CV in %) enables us to compare the different conditions independently of their absolute thickness (Figure S1). The film spatial homogeneity was in the order: T_10% ~T_0% > nT_10% > nT_0%. The mean film thickness in each microwell, hWELL (Figure 2e) was systematically and significantly lower for the T conditions (median value of the order of 1.6 μm versus 2.1 μm). In addition, hWELL was more homogenous for the two T conditions, as evidenced by the lower CV of hWELL (Figure 2f). The best homogeneity was obtained for the T_10% condition (CV < 7%) (Table 1) most probably because it avoids a liquid meniscus in the wells.

Figure 2. Homogeneity of biomimetic films deposited at the bottom of multiple well plates using the robotic arm.

(a-d) (PLL/HA)12 film homogeneity inside each microwell of a 96-well cell culture plate was assessed similarly for the 4 different experimental conditions: non tilting or tilting (nT or T) the plate carrier, with no or additional volume aspiration (0% or 10%), i.e. nT_0%, nT_10%, T_0%, T_10%. For each condition, the global tile scan view of the film (inset image) enables to plot the corresponding histogram of fluorescence intensities of all pixels. 3 representative histograms are shown for each condition (continuous light gray, dark gray and black lines). The mean thickness is pooled at each of the 5 positions (hN, hW, hC, hE, hS) (mean ± SD of m=48 microwells in 3 independent experiments with at least 6 wells/experiment). (e) Box-plot representation of the inter-microwell reproducibility, assessed by plotting hWELL (m=48). (f) The corresponding CV (SD/mean for these measurements), expressed in %, is also shown (see Table 1 for the quality scores). * p < 0.05

Table 1.

Experimental values of all parameters studied for the four experimental conditions. Based on these values, a quality score from 1 to 5 was attributed for each criterion. The total mean score was then calculated, leading to the following ranking: T_10% > T_0% > NT_10% > NT_0%.

| PARAMETER | NT_0% | NT_10% | T_0% | T_10% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD of CVs of all positions | 19,3 ± 9,8 | 20,6 ± 5,4 | 7,1 ± 3,9 | 5,1 ± 0,5 | |

| Quality score | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | |

| CV of hWELL (%) | 18,3 | 20,3 | 14 | 6,8 | |

| Quality score | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| Global film homogeneity (Tile scans) | 0,742 | 1,004 | 0,172 | 0,177 | |

| Quality score | 2 | 1 | 5 | 5 | |

| TOTAL QUALITY SCORE (mean) | 2,0 | 1,7 | 4,0 | 5,0 | |

We confirmed for thicker films made of 24 layer pairs that both plate tilting (Figure S2) and additional aspiration (Figure S3) improved film thickness homogeneity. The Z-position of the tip needs to be manually defined by the user before beginning each experiment. Indeed, the reference position Z0 was set to 0.1 mm above the plate in order to ensure that the tip is not touching the bottom of the plate. We investigated the influence of Z0 positioning on hWELL by increasing Z0 stepwise by 0.3 mm (Figure S4). The dispersion in film thickness increased with Z0 for the NT conditions and the T_0%. In striking contrast, the values remained independent of Z0 for the T_10% condition. Therefore, the T_10% is very interesting since it is more permissive for the user in the sense that it does not require a precise optimization of Z0. In view of the superiority of the T_10% condition, confirmed by its global quality score (Table 1), we used this condition for further experiments.

To date, experimentalists doing biological assays in 96-well microplates needed to build the films by hand using a multiple-channel pipette [31, 32]. First, this procedure is tedious since the operator needs to stay focused for several hours and up to ~2 days for films made of 24 bilayers. Secondly, this procedure is user-dependent and is prone to errors. We compared LbL films made using the automated procedure to hand-made films (Figure S5). Unsurprisingly, the automatized procedure proved to be superior to the manual procedure (CV of 6% in comparison to 21% for hand-made films).

Instead of handling liquids, users were commonly handling glass slides or plates using a dip-coating robot to dip them into a given polyelectrolyte solution [19, 31]. Then, the slides were transferred to cell-culture plates [33]. In case the user wanted to image cells at high resolution using optical microscopes, the slides had to be mounted on coverslips[33]. All these steps are time consuming and prone to human errors. We thus compared the biomimetic films built using liquid handling directly in microplates, and imaged directly at the bottom of the microplates, to those built on glass sides by dip-coating and imaged after being mounted on a coverslip (Figure S6). The films built using dip-coating robot were thinner (4.1 + 0.6 μm versus 7.8 + 0.5 μm) and slightly less homogeneous (14.1 % versus 6.9 %) than those built using the liquid handling robot. The renewal of the polyelectrolyte solutions during liquid handling may well explain the increase in thickness. Advantageously, the automated liquid handling robot enables us to screen the effect of several parameters on h, such as polyelectrolyte concentrations, in order to select the future working conditions. In situ analysis using confocal microscopy, ex-situ analysis of the internal structure of the film using infrared spectroscopy and of film thickness using profilometry revealed a clear concentration-dependence of h when both PLL and HA concentrations were decreased (Figure S7). Thus, the user can easily choose their working conditions depending on their needs, or screen for experimental conditions, highlighting the versatility of the liquid handling robot.

Finally, we extended the automated deposition process to other polyelectrolyte couples to highlight its applicability to a variety of LbL films. We selected other biopolymers that are already widely used in tissue engineering and as LbL components, namely poly(L-glutamic acid) (PGA) and chitosan (CHI) [34]. Both (CHI/PGA) films (Figure S8) and (PLL/PGA) films (Figure S9) were homogeneous. Notably, very thin films made of the linearly growing (PSS/PAH) system were also shown to grow linearly (Figure S10), in agreement with previous studies [35]. This highlights the adaptability of the automated liquid handling to deposit LbL film over a wide range of film thicknesses.

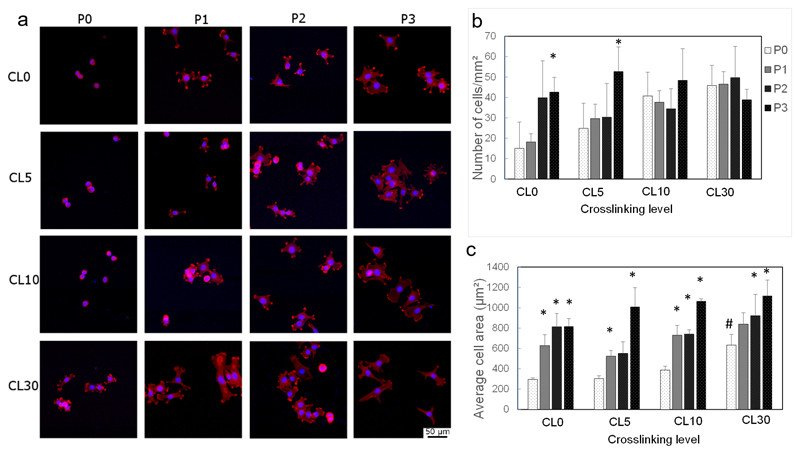

Having proved the versatility of the automated LbL deposition method to build a variety of LbL films in microplates, we first assessed its potential to screen for cell adhesion and spreading (Figure 3). To this end, we used C2C12 myoblasts and the already well-established (PGA/PLL) LbL films, ending with a peptide-grafted PGA layer, that we previously studied for myoblast cell adhesion [36]. Film crosslinking was previously shown to increase film stiffness [37]. 16 different conditions were compared for (PGA/PLL)5 films by screening a matrix of 4 crosslinking levels and 4 peptide concentrations: the films were either native (CL0) or crosslinked to different levels (CL5, CL10, and CL30). The PGA-RGD layer was added as a final layer at increasing concentrations corresponding to increasing ratios of PGA/PGA-RGD: P0 (3/0, i.e. no peptide), P1 (2/1), P2 (1/2), P3 (0/3). The number of adherent cells (Figure 3b) and the cell spreading area (Figure 3c) were assessed by nucleus and actin staining respectively, followed by automated quantification with custom-made ImageJ macros. The cell number increased with the concentration of the RGD-peptide for the native (CL 0) and slightly crosslinked (CL 5) films, but it was peptide-independent for higher crosslinked films (CL 10 and CL30) (Figure 3b). Besides, a clear peptide-dependent cell spreading area was visible for all crosslinking conditions (Figure 3c). If one solely compares the effect of CL in the absence of peptide (P0), the CL30 condition is significantly different from the CL0 conditions (Figure 3c).

Figure 3. Screening of cell adhesion and spreading onto biomimetic films of controlled stiffness and bioactivity deposited at high throughput in microplates.

PGA/PLL films were built automatically with the robot using the T_10% condition. (a) Representative images of the nuclei and actin cytoskeleton for C2C12 myoblasts grown on PGA-RGD-ending films of controlled crosslinking. The actin cytoskeleton was stained with rhodamine-phalloidin and observed with a 20X objective. Matrix of 16 conditions in total: 4 PGA-RGD peptide concentrations (P0, P1, P2 and P3) and 4 crosslinking levels (CL0, CL5, CL10 and CL30); (b) Automated quantification for all experimental conditions of the number of adherent cells/mm2 (c) and the average cell area (μm2) (d) covered by the cells. Data are mean ± SD of at least 3 independent microwells and 2 independent experiments. * p < 0.05 with respect to the P0 condition in each of the 4 CL subgroup. # p < 0.05 when comparing, at P0, the 4 CL groups.

Thus, cell adhesion and spreading on biomimetic films deposited at the bottom of microplates can quickly be assessed by optical imaging at high throughput.

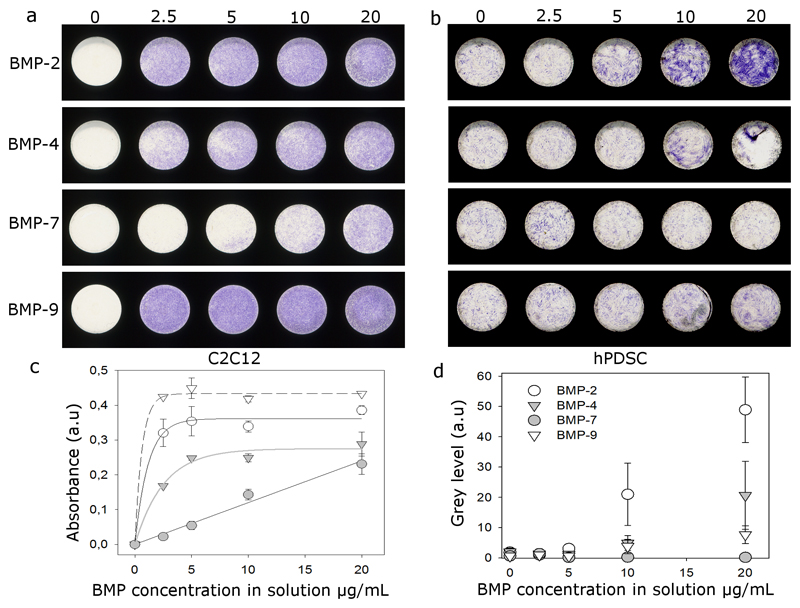

To further study the potential to assess stem cell differentiation at high throughput using film-coated microplates, we studied the differentiation of skeletal progenitors into bone cells (Figure 4). Using C2C12 muscle cells and human periosteum derived stem cells (hPDSCs) as bone morphogenetic responsive cells [38] [39], we screened 16 different experimental conditions: 4 different BMP proteins (BMP-2, 4, 7, 9) that are important in cell differentiation to bone [38] and 4 increasing loading concentrations of BMPs in the films (0, 2.5, 10 and 20 μg/mL). We first verified that all the BMPs could be loaded in the biomimetic films (Table S1), similarly to what we had previously showed for BMP-2 [33]. Cell differentiation into bone, as quantified by the expression of alkaline phosphatase (ALP), was assessed after 3 days of culture for C2C12 cells (Figure 4a,c) and 14 days for hPDSCs (Figure 4b,d). ALP expression in all microwells was visualized using a scanner (Figure 4a and b), and quantified at high throughput using two methods: i) quantification of the absorbance of ALP using a microplate reader (Figure 4c) and ii) quantitative analysis of pixel intensities of each microwell using ImageJ (Figure 4d). For C2C12 cells, the ALP expression increases in a dose-dependent manner depending on the type of BMP, in the order bBMP-9 > 2 > 4 > 7, which is slightly different to what has been observed for soluble BMPs and C2C12 cells [38, 40]. The ALP responses for bBMP-2, 4 and 9 data were fitted with an exponential function (continuous and dashes lines) (Table S2) while ALP expression increased in a linear manner for bBMP-7. In contrast, hPDCS cells mainly responded, and in a linear manner to BMP-2 > 4 > 9, and did not respond to BMP-7. This is in agreement with previous findings obtained with soluble BMPs [41].

Figure 4. High throughput screening of stem cell differentiation on bioactive LbL films in microplates.

(PLL/HA)12 films were prepared using the liquid handling robot in the T_10% condition and crosslinked with EDC70. LbL films were post-loaded with 4 different BMP proteins (BMP-2, 4, 7, 9) at 5 increasing concentrations of BMP in solution (from 0 to 20 μg/mL), representing 20 different experimental conditions in total. 5000 C2C12 cells and hPDSCs/well were cultured in growth medium for 3 and 14 days, respectively, before being stained for ALP. Representative images of ALP stained microwells taken with a scanner for C2C12 (a) and hPDSCs (b). For C2C12 cells (c), quantitative analysis of ALP expression was made by measuring the absorbance at 570 nm using a Tecan microplate reader in multiple-read/well mode shown. For hPDSCs (d), the mean gray level of each microwell was measured by ImageJ. Experiments were reproduced 3 times (i.e. new film buildup and new cell culture) with 2 independent microwells per condition in each experiment.

To note, the number of stem cells needed for the experiments is also reduced when 96well plate are used: the surface of microwells being respectively of 0,34 cm2, 0,95 cm2 and 1.9 cm2 for 96-, 48 and 24-well plates. This leads to a ~6 fold decrease of surface for 96 well plates in comparison to 24-well plates, and ~3 fold when compared to 48 wells. Being able to decrease the number of cell and culture media needed to perform experiments is advantageous when precious cells such as stem cells are studied.

In the future, it could also be envisioned to study the combined effects of film stiffness and bioactive molecules on stem cells differentiation.

Altogether, our data show that it is possible to screen stem cell differentiation on bioactive films at high throughput. Our data also show that it is possible to culture stem cells on the bioactive films for at least two weeks.

Automated liquid handling using optimized working conditions, i.e. tilting of the plate carrier and aspiration of an additional excess volume, enables to deposit LbL films at the bottom of 96-well microplates with a CV below 7%. Advantageously, in view of their optical transparency, optical microscopies and spectroscopies can be carried out in an automated manner, and data can also be analyzed automatically. Multiple assays can be performed on the same plate, including film characterization, cellular imaging and bioactivity tests. Very interestingly, this new method is easily adaptable to other type of microplates with a lower number of wells, to high resolution imaging techniques such as total internal reflection microscopy, and is also adaptable to any type of robotic arm regardless of the manufacturer.

Experimental Section

Polyelectrolytes, buffers, film crosslinking and biofunctionality

Poly(L-lysine) hydrobromide (PLL), poly(ethylene imine) (PEI), poly(L-glutamic) acid (PGA) were from Sigma-Alrich (St Quentin Fallavier, France), hyaluronic acid (HA) from Lifecore medical (USA). For biological functionalization, PGA-RGD was synthesized as previously described [36]. PLL, HA and PEI at respectively 0.5, 1 and 2 mg/mL were dissolved in a HEPES-NaCl buffer (20 mM Hepes at pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl). A first layer of PEI was always deposited. All rinsing steps were performed with 0.15 M NaCl at pH ~6.5. The films were chemically crosslinked using 1-Ethyl-3-(3-Dimethylamino-propyl)Carbodiimide (EDC, final concentration of 5, 10, 30 or 70 mg/mL depending of the films) and N-Hydrosulfosuccinimide sodium salt (Sulfo-NHS, 11 mg/mL) as catalyzer, as previously described [32, 42]. BMP loading in the films was done following an established protocol [31, 33].

Automated film buildup using a liquid handling robot

LbL films were directly deposited in 96-well cell culture microplates (Greiner bio-one, Germany) using an automated liquid handling machine (TECAN Freedom EVO® 100, Tecan France, Lyon). The plate was tilted using a tilting plate carrier (Tecan). A custom-made macro was designed to program the LbL film buildup according to the user’s need (number and position of the microwells, number of deposited layer pairs, and incubation time in each polyelectrolyte and rinsing solution). We applied the following sequence: (i) dispensing of polyelectrolyte solution (polycation or polyanion); (ii) incubation for a given time period; iii) aspiration back and dispensing in the trash; iv) two rinsing steps with salt solution following the same procedure. This sequence is repeated 2xi times to build a layer-by-layer film made of i layer pairs. The pipetting speed was set to 150-800 μL/s for the dispense step and 100-150 μL/s for the aspiration steps.

Characterization of the homogeneity of films deposited in microplates

Characterization was done in situ in liquid using confocal microscopy for optical imaging (Zeiss LSM 700). Film homogeneity was assessed using a fluorescently labeled PLL (PLLFITC) and imaging of global film homogeneity inside each microwell by acquiring tile scan images using a 10X objective. Based on PLLFITC [30], we quantified film thickness h on automatically acquired Z-stacks (X63 objective) at the 5 selected positions (hC, hN, hE, hS, hW): center of the well and all 4 poles, each being positioned at ± 2 mm from the center in the X or Y direction. h was automatically deduced from the fluorescence intensity profile (see below and Figure 1F).

The mean thickness/ well (hWELL) is defined as:

| Equation (1) |

The mean thickness of m independent wells (hMEAN) was calculated as:

| Equation (2) |

The standard deviation “SD” of hWELL for m independent wells was calculated as:

| Equation (3) |

The Coefficient of Variation (CV) of the mean thickness/well was calculated as:

| Equation (4) |

CV (in %) was used to compare samples independently of their absolute thickness values.

Quantification of cell adhesion in response to RGD-containing adhesive peptide

The (PGA/PLL)5 films built using the liquid handling robot were rinsed with the Hepes-NaCl buffer using the robot, before a final layer composed of a GA/PGA-RGD mixture at a fixed ratio was deposited. 3500 C2C12 myoblasts/well were cultured on the films for 1 H in a serum-free medium. Tile scan images (4x4 fields for each microwell) were acquired automatically using a 20X objective in two channels after staining nuclei with DAPI (Life Technologies) and the actin cytoskeleton with Rhodamine-phalloidin (Sigma).

Quantification of stem cell differentiation in response to biomimetic films

We used two types of BMP responsive cells, skeletal myoblasts [31] and periosteum-derived stem cells (hPDSCs) [39] to assess the bioactivity of the biomimetic coatings at high throughput. C2C12 skeletal myoblasts (< 25 passages, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, ATCC) and hPDSC (<12 passages, obtained from F. Luyten) were cultured as previously described [31, 39] in tissue culture flasks, in a 1:1 Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM):Ham’s F12 medium (Gibco, Invitrogen, France) for C2C12 and in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified medium (high DMEM) for hPDSC, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, PAA Laboratories, France) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco, Invitrogen, France) in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator. 15 000 cells/cm2 in their medium were seeded in each well. After 3 days of culture for C2C12 and 14 days for hPDSC, the growth medium was removed and cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde. ALP was stained using fast blue RR salt in a 0.01 % (w/v) naphthol AS-MX solution (Sigma Aldrich), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ALP staining was quantified at high throughput using a TECAN Infinite 1000 microplate reader (TECAN France, Lyon) by quantifying the absorbance at 570 nm using the multiple-read/well mode: 76 different positions were measured in each microwell and the mean value was taken. For hPDSCs, the mean gray level of each microwell was quantified using Image J.

Automated data analysis using custom-made Image J macros

For measurement of the film thickness h, a typical fluorescence intensity profile starts off at the noise level (~ 0), increases to a peak value and returns to the noise level (Figure 1d). The maximum intensity (FMAX) was first determined. We then applied a threshold coefficient K so that I=K x FMAX and deduced the Z position (Z1, Z2) at which this line intercepts the fluorescence intensity profile. h (in μm) = Z2-Z1 was then easily deduced. We validated this macro by comparing film thicknesses obtained using the macro, manual measurement and measurement made by atomic force microscopy.

Another macro was written for the measurement of the cell number and mean spreading area. Briefly, images of the nuclei were binarized using an intensity threshold, and touching nuclei were separated using the watershed function. Objects within an area range consistent with the size of a nucleus were counted in order to obtain the total cell number in the acquired field. Nuclei at the edges of the image were excluded. For the actin cytoskeleton, images were also first binarized using an intensity threshold. Objects too small to be cells were removed and cells at the edges of the image were also excluded, as there is no way of knowing their exact area. The total cell area over the entire field was then measured.

Data representation and statistical analysis

For box plots, the box shows 25, 50 and 75% as well as 10% lower and 90% upper values (as upper bars). Experiments were performed in duplicate or triplicate, with 2 or 3 samples per condition in each experiment. Statistical analysis was performed between more than two groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and pair wise comparisons to obtain p values (p < 0.05 was considered significant)

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by ERC BIOMIM (GA259370), ERC BioactiveCoating (GA692924), Institut Universitaire de France and ANR PIRE REACT (ANR-15-PIRE-0001-02). We thank Thomas Boudou for AFM measurements ex-situ and scientific discussions. We thanks Prof Franz Luyten for providing the hPDSCs cells and Dr Benoit Frisch for providing the PGA-RGD. We are grateful to Xavier Saunier, Thomas Laoué and Jean-Daniel Audibert from Tecan for their technical advices.

Bibliographic references

- [1].Schena M, Shalon D, Davis RW, Brown PO. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science. 1995;270:467. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Algahtani MS, Scurr DJ, Hook AL, Anderson DG, Langer RS, Burley JC, Alexander MR, Davies MC. High throughput screening for biomaterials discovery. J Control Release. 2014;190:115. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Patel AK, Tibbitt MW, Celiz AD, Davies MC, Langer R, Denning C, Alexander MR, Anderson DG. High throughput screening for discovery of materials that control stem cell fate. Curr Opin Solid State Mat Sci. 2016;20:202. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Beachley VZ, Wolf MT, Sadtler K, Manda SS, Jacobs H, Blatchley MR, Bader JS, Pandey A, Pardoll D, Elisseeff JH. Tissue matrix arrays for high-throughput screening and systems analysis of cell function. Nat Methods. 2015;12:1197. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Muller E, Pompe T, Freudenberg U, Werner C. Solvent-assisted micromolding of biohybrid hydrogels to maintain human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells ex vivo. Adv Mater. 2017;29:7. doi: 10.1002/adma.201703489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Seo J, Shin JY, Leijten J, Jeon O, Camci-Unal G, Dikina AD, Brinegar K, Ghaemmaghami AM, Alsberg E, Khademhosseini A. High-throughput approaches for screening and analysis of cell behaviors. Biomaterials. 2018;153:85. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Anderson DG, Levenberg S, Langer R. Nanoliter-scale synthesis of arrayed biomaterials and application to human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:863. doi: 10.1038/nbt981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mei Y, Saha K, Bogatyrev SR, Yang J, Hook AL, Kalcioglu ZI, Cho SW, Mitalipova M, Pyzocha N, Rojas F, Van Vliet KJ, et al. Combinatorial development of biomaterials for clonal growth of human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Mater. 2010;9:768. doi: 10.1038/nmat2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Flaim CJ, Teng D, Chien S, Bhatia SN. Combinatorial signaling microenvironments for studying stem cell fate. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17:29. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ranga A, Gobaa S, Okawa Y, Mosiewicz K, Negro A, Lutolf MP. 3D niche microarrays for systems-level analyses of cell fate. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4324. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Holle AW, McIntyre AJ, Kehe J, Wijesekara P, Young JL, Vincent LG, Engler AJ. High content image analysis of focal adhesion-dependent mechanosensitive stem cell differentiation. Integr Biol. 2016;8:1049. doi: 10.1039/c6ib00076b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Thakur A, Mishra S, Pena J, Zhou J, Redenti S, Majeska R, Vazquez M. Collective adhesion and displacement of retinal progenitor cells upon extracellular matrix substrates of transplantable biomaterials. Journal of tissue engineering. 2018;9 doi: 10.1177/2041731417751286. 2041731417751286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Celiz AD, Smith JG, Patel AK, Hook AL, Rajamohan D, George VT, Flatt L, Patel MJ, Epa VC, Singh T, Langer R, et al. Discovery of a novel polymer for human pluripotent stem cell expansion and multilineage differentiation. Adv Mater. 2015;27:4006. doi: 10.1002/adma.201501351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Engler AJ, Griffin MA, Sen S, Bonnemann CG, Sweeney HL, Dische DE. Myotubes differentiate optimally on substrates with tissue-like stiffness: pathological implications for soft or stiff microenvironments. Journal of Cell Biology. 2004;166:877. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Matrigen. Softwell hydrogel coated wells User guide. available at matrigen.com. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Decher G. Fuzzy nanoassemblies: Toward layered polymeric multicomposites. Science. 1997;277:1232. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Boudou T, Crouzier T, Ren K, Blin G, Picart C. Multiple functionalities of polyelectrolyte multilayer films: new biomedical applications. Adv Mater. 2010;22:441. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Smith RC, Riollano M, Leung A, Hammond PT. Layer-by-layer platform technology for small-molecule delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:8974. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gribova V, Auzely-Velty R, Picart C. Polyelectrolyte multilayer assemblies on materials surfaces: From cell adhesion to tissue engineering. Chem Mat. 2012;24:854. doi: 10.1021/cm2032459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Richardson JJ, Bjornmalm M, Caruso F. Multilayer assembly. Technology-driven layer-by-layer assembly of nanofilms. Science. 2015;348 doi: 10.1126/science.aaa2491. aaa2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Richardson JJ, Liang K, Kempe K, Ejima H, Cui J, Caruso F. Immersive polymer assembly on immobilized particles for automated capsule preparation. Adv Mater. 2013;25:6874. doi: 10.1002/adma.201302696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gilbert JB, Rubner MF, Cohen RE. Depth-profiling X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis of interlayer diffusion in polyelectrolyte multilayers. PNAS. 2013;110:6651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222325110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schaaf P, Voegel JC, Jierry L, Boulmedais F. Spray-assisted polyelectrolyte multilayer buildup: from step-by-step to single-step polyelectrolyte film constructions. Adv Mater. 2012;24:1001. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Krogman KC, Zacharia NS, Schroeder S, Hammond PT. Automated process for improved uniformity and versatility of layer-by-layer deposition. Langmuir. 2007;23:3137. doi: 10.1021/la063085b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chiarelli PA, Johal MS, Casson JL, Roberts JB, Robinson JM, Wang HL. Controlled fabrication of polyelectrolyte multilayer thin films using spin-assembly. Adv Mater. 2001;13:1167. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sailer M, Lai Wing Sun K, Mermut O, Kennedy TE, Barrett CJ. High-throughput cellular screening of engineered ECM based on combinatorial polyelectrolyte multilayer films. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5841. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Castleberry SA, Li W, Deng D, Mayner S, Hammond PT. Capillary flow layer-by-layer: a microfluidic platform for the high-throughput assembly and screening of nanolayered film libraries. ACS nano. 2014;8:6580. doi: 10.1021/nn501963q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jaklenec A, Anselmo AC, Hong J, Vegas AJ, Kozminsky M, Langer R, Hammond PT, Anderson DG. High Throughput Layer-by-Layer Films for Extracting Film Forming Parameters and Modulating Film Interactions with Cells. ACS applied materials & interfaces. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b11081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Picart C, Mutterer J, Richert L, Luo Y, Prestwich GD, Schaaf P, Voegel J-C, Lavalle P. Molecular basis for the explanation of the exponential growth of polyelectrolyte multilayers. PNAS. 2002;99:12531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202486099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Crouzier T, Ren K, Nicolas C, Roy C, Picart C. Layer-by-Layer films as a biomimetic reservoir for rhBMP-2 delivery: controlled differentiation of myoblasts to osteoblasts. Small. 2009;5:598. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gribova V, Gauthier-Rouviere C, Albiges-Rizo C, Auzely-Velty R, Picart C. Effect of RGD functionalization and stiffness modulation of polyelectrolyte multilayer films on muscle cell differentiation. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:6468. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Crouzier T, Fourel L, Boudou T, Albiges-Rizo C, Picart C. Presentation of BMP-2 from a soft biopolymeric film unveils its activity on cell adhesion and migration. Adv Mater. 2011;23:H111. doi: 10.1002/adma.201004637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Silva JM, Reis RL, Mano JF. Biomimetic extracellular eEnvironment based on natural origin polyelectrolyte multilayers. Small. 2016;12:4308. doi: 10.1002/smll.201601355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Picart C, Gergely C, Arntz Y, Schaaf P, Voegel J-C, Cuisinier FG, Senger B. Measurement of film thickness up to several hundreds of nanometers using optical wavguide lightmode spectroscopy. Biosensors Bioelectronics. 2004;20:553. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Picart C, Elkaim R, Richert L, Audoin F, Da Silva Cardoso M, Schaaf P, Voegel J-C, Frisch B. Primary cell adhesion on RGD functionalized and covalently cross-linked polyelectrolyte multilayer thin films. Adv Funct Mat. 2005;15:83. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Schneider A, Bolcato-Bellemin A-L, Francius G, Jedrzejwska J, Schaaf P, Voegel J-C, Frisch B, Picart C. Glycated polyelectrolyte multilayer films : differential adhesion of primary versus tumor cells. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:2882. doi: 10.1021/bm0605208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Rivera JC, Strohbach CA, Wenke JC, Rathbone CR. Beyond osteogenesis: an in vitro comparison of the potentials of six bone morphogenetic proteins. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:7. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bolander J, Ji W, Geris L, Bloemen V, Chai YC, Schrooten J, Luyten FP. The combined mechanism of bone morphogenetic protein and calcium phosphate-induced skeletal tissue formation by human periosteum derived cells. Eur Cells Mater. 2016;31:11. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v031a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Luu HH, Song WX, Luo XJ, Manning D, Luo JY, Deng ZL, Sharffl KA, Montag AG, Haydon RC, He TC. Distinct roles of bone morphogenetic proteins in osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:665. doi: 10.1002/jor.20359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bolander J, Ji W, Leijten J, Teixeira LM, Bloemen V, Lambrechts D, Chaklader M, Luyten FP. Healing of a large long-bone defect through serum-free in vitro priming of human periosteum-derived cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2017;8:758. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Schneider A, Francius G, Obeid R, Schwinté P, Frisch B, Schaaf P, Voegel J-C, Senger B, Picart C. Polyelectrolyte multilayer with tunable Young's modulus : influence on cell adhesion. Langmuir. 2006;22:1193. doi: 10.1021/la0521802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.