Abstract

We used the Mendelian randomization design to explore the potential causal association of smoking with ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage using summary statistics data for 34,217 ischemic stroke cases and 404,630 noncases, and 1,545 cases of intracerebral hemorrhage and 1,481 noncases. Genetic predisposition to smoking initiation (ever smoking regularly), based on up to 372 single‐nucleotide polymorphisms, was statistically significantly positively associated with any ischemic stroke, large artery stroke, and small vessel stroke but not cardioembolic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage. This study provides genetic support for a causal association of smoking with ischemic stroke, particularly large artery and small vessel stroke. ANN NEUROL 2019;86:468–471

Evidence from observational studies indicates that smoking increases the risk of stroke.1 Even smoking as little as 1 cigarette per day is associated with an approximately 25% to 30% increased risk of stroke.1 However, the role of smoking for ischemic stroke subtypes and intracerebral hemorrhage is unclear. Moreover, because data on smoking in relation to stroke originate from observational studies, which are vulnerable to confounding, the causal nature of the association between smoking and stroke risk remains elusive. We therefore implemented the Mendelian randomization (MR) design to assess the association of genetic predisposition to smoking with ischemic stroke and its main subtypes as well as intracerebral hemorrhage. MR is a method that can be used to strengthen causal inference in observational studies by utilizing genetic variants associated with the exposure as instrumental variables for the exposure.2

Subjects and Methods

Outcome Data

The current study is based on publicly available summary statistics data for genetic associations with ischemic stroke and its subtypes from the MEGASTROKE consortium, including data for 438,847 European‐descent individuals (34,217 ischemic stroke cases and 404,630 noncases).3 The cases were subtyped according to the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment criteria4 into large‐artery (n = 4,373), small vessel (n = 5,386), and cardioembolic (n = 7,193) stroke. Summary statistics data for intracerebral hemorrhage were available from a genome‐wide association meta‐analysis of 3,026 European‐descent individuals (1,545 cases and 1,481 noncases).5 The present MR study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority.

Selection of Instrumental Variables

A genome‐wide association meta‐analysis of 1,232,091 individuals identified 378 conditionally independent single‐nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at 259 loci (defined as a 1Mb region surrounding the top p value) associated with ever smoking regularly (hereafter referred to as smoking initiation) at genome‐wide significance.6 Conditionally independent SNPs had been identified using the novel, partial correlation‐based score statistic method.7 The 378 SNPs explained 2.3% of the phenotypic variation in smoking initiation. Thirteen and 113 SNPs were unavailable in the ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage datasets, respectively. A proxy SNP in linkage disequilibrium (R 2 > 0.7) with the specified SNP was identified for 7 and 61 of the missing SNPs for ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage datasets, respectively. Thus, the smoking initiation analyses included 372 SNPs in the analysis of ischemic stroke and 326 SNPs in the analysis of intracerebral hemorrhage.

As an additional analysis, we used 126 SNPs associated with a measure of lifetime smoking exposure that takes into account smoking status and, among ever smokers, duration, heaviness, and cessation.8 These SNPs were broadly distinct from the SNPs predicting smoking initiation (only 9 SNPs overlapped) and strongly associated with the positive control of lung cancer.8 All 126 SNPs were available in the ischemic stroke dataset, whereas 109 SNPs (including 41 proxy variants) were available for analysis of intracerebral hemorrhage. In a further secondary analysis, we used 53 conditionally independent genome‐wide significant SNPs associated with cigarettes smoked per day in a genome‐wide association meta‐analysis of 337,334 ever smokers,6 which were available in the ischemic stroke dataset.

There was partial sample overlap between the 3 smoking phenotypes. The genome‐wide association studies of smoking initiation, lifetime smoking exposure, and cigarettes per day included, respectively, 383,631 (of the total 1,232,091 individuals), 462,690, and 337,334 individuals from UK Biobank.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using the mrrobust9 and MendelianRandomization10 packages. The principal analysis was conducted using the inverse‐variance weighted method, under a random‐effects model, and supplemented with the weighted median approach.11 The MR‐Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier and MR‐Egger regression methods were used to identify outliers and pleiotropy.11, 12 Smoking initiation is genetically correlated with alcohol consumption (r g = 0.34) and education (r g = −0.40).6 In a multivariable MR analysis, we included SNPs associated with those exposures6, 13 along with SNPs for smoking initiation. To correct for multiple testing, we applied a Bonferroni‐corrected significance threshold of α = 0.01 (where α = 0.05/5 outcomes).

Results

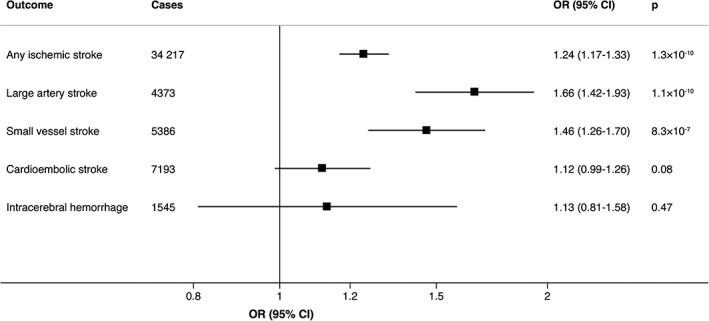

Genetic predisposition to smoking initiation was statistically significantly positively associated with any ischemic stroke, large artery stroke, and small vessel stroke but not cardioembolic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage in analyses using the inverse‐variance weighted method (Fig 1). Results were similar in a sensitivity analysis based on the weighted median method; the odds ratios per unit increase in log odds of ever smoking regularly were 1.22 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.12–1.34, p = 7.6 × 10−6) for any ischemic stroke, 1.59 (95% CI = 1.26–1.99, p = 6.7 × 10−5) for large artery stroke, 1.35 (95% CI = 1.09–1.66, p = 0.005) for small vessel stroke, 1.11 (95% CI = 0.94–1.32, p = 0.21) for cardioembolic stroke, and 0.83 (95% CI = 0.50–1.37, p = 0.47) for intracerebral hemorrhage. One outlier SNP was identified in the analyses of any ischemic stroke but none in the analyses of the other outcomes. Exclusion of the outlier did not essentially change the results for smoking and ischemic stroke (odds ratio = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.15–1.31, p = 6.5 × 10−10). There was no indication of directional pleiotropy (all p > 0.24). Restricting the analysis to 1 SNP in each locus yielded similar results (odds ratio of ischemic stroke = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.14–1.33, p = 7.0 × 10−8). The association between genetic predisposition to smoking initiation and ischemic stroke was weaker but remained statistically significant in multivariable MR analysis that included SNPs for alcohol consumption and education (odds ratio = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.07–1.23, p = 1.8 × 10−4).

Figure 1.

Associations of genetic predisposition to smoking initiation with ischemic stroke and its subtypes and intracerebral hemorrhage. Odds ratios are expressed per unit increase in log odds of ever smoking regularly (smoking initiation). Estimates were obtained using the inverse variance‐weighted method under a random‐effects model. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

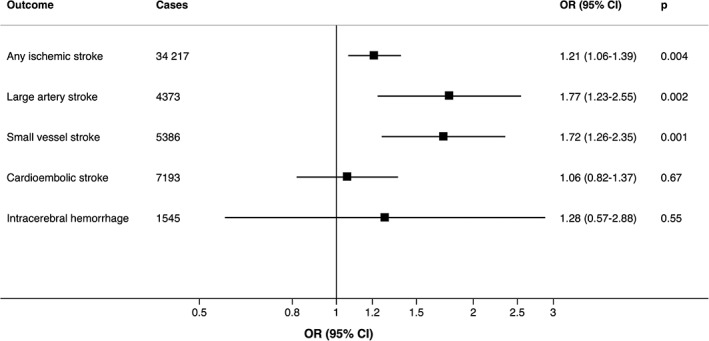

Findings were similar in analyses of lifetime smoking exposure (Fig 2). Genetically predicted cigarettes smoked per day was positively associated with ischemic stroke, but the association was not statistically significant in the inverse‐variance weighted analysis. The odds ratio was 1.14 (95% CI = 0.98–1.33, p = 0.09) per 1 standard deviation (corresponding to about 8 cigarettes per day among current smokers in the UK Biobank) increase in cigarettes per day.

Figure 2.

Associations of genetically predicted lifetime smoking index with ischemic stroke and its subtypes and intracerebral hemorrhage. Odds ratios are expressed per 1 standard deviation increase of the lifetime smoking index. Estimates were obtained using the inverse variance‐weighted method under a random‐effects model. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Discussion

This study provides genetic support for a causal association between smoking and increased risk of ischemic stroke, particularly large artery and small vessel stroke. We found no causal association between smoking and cardioembolic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage.

Cigarette smoke can adversely affect the cardiovascular system through its content of oxidant gases (eg, oxides of nitrogen and free radicals) and other toxic substances, which may increase stroke risk through endothelial dysfunction, lipid oxidation, inflammation, platelet activation, thrombogenesis, and enhanced coagulability.14 Additionally, nicotine may reduce cerebral blood flow.14

Notable strengths of this MR study are that the analyses were based on large sample sizes for ischemic stroke and a robust genetic instrument for smoking initiation, comprising 372 SNPs. Thus, we had high statistical power to detect weak associations with ischemic stroke. Nonetheless, the analyses of intracerebral hemorrhage were based on a small sample size and we cannot rule out that we may have overlooked a weak association between smoking and intracerebral hemorrhage. Population stratification can affect the findings of MR studies but we reduced this bias by using summary statistics data for individuals of European ancestry only.

A possible criticism of the use of smoking initiation as a phenotype is that it does not reflect exposure to cigarette smoke. Therefore, in a complementary analysis we investigated the association between a lifetime smoking index, which takes into account smoking intensity, and found broadly similar results. In an additional secondary analysis, we observed a suggestive, nonsignificant, dose‐response association between cigarettes smoked per day and ischemic stroke. However, that analysis suffered from low precision due to low phenotypic variation explained by the SNPs (about 1.1%–1.2%). Moreover, we were unable to stratify the analysis by smoking status and could not examine nonlinear associations.

In conclusion, this MR study found support for causal associations between smoking and increased risk of ischemic stroke as a whole, large artery stroke, and small vessel stroke, but not cardioembolic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage.

Author Contributions

S.C.L., S.B., and K.M. contributed to the conception and design of the study. S.C.L. contributed to the analysis of data, preparing the figures, and drafting the text.

The investigator list of MEGASTROKE is available at http://megastroke.org/authors.html.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nothing to report.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (Forskningsrådet för hälsa, arbetsliv och välfärd) and the Swedish Research Council. S.B. is supported by a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (grant number 204623/Z/16/Z). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Funding of the MEGASTROKE project is specified at megastroke.org/acknowledgements.html.

We thank the MEGASTROKE and International Stroke Genetics consortia for providing summary statistics data for ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage.

References

- 1. Hackshaw A, Morris JK, Boniface S, et al. Low cigarette consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: meta‐analysis of 141 cohort studies in 55 study reports. BMJ 2018;360:j5855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. 'Mendelian randomization': can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malik R, Chauhan G, Traylor M, et al. Multiancestry genome‐wide association study of 520,000 subjects identifies 32 loci associated with stroke and stroke subtypes. Nat Genet 2018;50:524–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 1993;24:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Woo D, Falcone GJ, Devan WJ, et al. Meta‐analysis of genome‐wide association studies identifies 1q22 as a susceptibility locus for intracerebral hemorrhage. Am J Hum Genet 2014;94:511–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu M, Jiang Y, Wedow R, et al. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat Genet 2019;51:237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jiang Y, Chen S, McGuire D, et al. Proper conditional analysis in the presence of missing data: application to large scale meta‐analysis of tobacco use phenotypes. PLoS Genet 2018;14:e1007452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wootton RE, Richmond RC, Stuijfzand BG, et al. Causal effects of lifetime smoking on risk for depression and schizophrenia: evidence from a Mendelian randomisation study. bioRxiv 2018;381301; doi: 10.1101/381301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spiller W, Davies NM, Palmer TM. Software application profile: mrrobust—a tool for performing two‐sample summary Mendelian randomization analyses. bioRxiv 2017;142125; doi: 10.1101/142125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yavorska OO, Burgess S. MendelianRandomization: an R package for performing Mendelian randomization analyses using summarized data. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:1734–1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burgess S, Bowden J, Fall T, et al. Sensitivity analyses for robust causal inference from Mendelian randomization analyses with multiple genetic variants. Epidemiology 2017;28:30–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet 2018;50:693–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee JJ, Wedow R, Okbay A, et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome‐wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat Genet 2018;50:1112–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rigotti NA, Clair C. Managing tobacco use: the neglected cardiovascular disease risk factor. Eur Heart J 2013;34:3259–3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]