Abstract

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) can affect high-level executive functioning long after somatic symptoms resolve. We tested if simple EEG responses within an oddball paradigm could capture variance relevant to this clinical problem. The P3a and P3b components reflect bottom-up and top-down processes driving engagement with exogenous stimuli. Since these features are related to primitive decision abilities, abnormal amplitudes following mTBI may account for problems in the ability to exert executive control. Sub-acute (<2 weeks) mTBI participants (N=38) and healthy controls (N=24) were assessed at an initial session as well as a two-month follow-up (sessions 1 and 2). We contrasted the initial assessment to a comparison group of participants with chronic symptomatology following brain injury (N=23). There were no group differences in P3a or P3b amplitudes. Yet in the sub-acute mTBI group, higher symptomatology on the Frontal Systems Behavior scale (FrSBe), a questionnaire validated as measuring symptomatic distress related to frontal lobe injury, correlated with lower P3a in session 1. This relationship was replicated in session 2. These findings were distinct from chronic TBI participants, who instead expressed a relationship between increased FrSBe symptoms and a lower P3b component. In the sub-acute group, P3b amplitudes in the first session correlated with the degree of symptom change between sessions 1 and 2, above and beyond demographic predictors. Controls did not show any relationship between FrSBe symptoms and P3a or P3b. These findings identify symptom-specific alterations in neural systems that vary along the time course of post-concussive symptomatology.

Keywords: TBI, executive, post-concussive, P3a, P3b, EEG

1. Introduction

The lingering distress following an acute mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) can take many forms. Any cognitive, emotional, or somatic symptom endorsement beyond three months post-injury may be described as prolonged post-concussive symptoms (PPCS: Bigler, 2008; Quinn, Mayer, Master, & Fann, 2018; Rose, Fischer, & Heyer, 2015). A large number of individuals experience PPCS, with up to 3/4 of individuals expressing at least one persistent symptom 6 months later (van der Naalt, Timmerman, de Koning, van der Horn, Scheenen, Jacobs, Hageman, Yilmaz, et al., 2017), and 1/4 still experiencing significant impairment 1 year later (McMahon et al., 2014). Importantly, many aspects of PPCS are not always expressed in readily recognizable dysfunction such as impaired daily functioning or somatic distress; they often impact quality of life in subtle and complex ways such as diminished high-level executive functioning (McDonald, Flashman, & Saykin, 2002).

Poorer long-term outcomes following mTBI can be predicted from demographic features such as female sex, older age, and low education, each of which may interact with other predictors like injury/symptom severity, poor coping skills and prior psychiatric or neurological disorders, including prior brain injuries (Mayer, Quinn, & Master, 2017; Mott, McConnon, & Rieger, 2012; Quinn et al., 2018; van der Naalt, Timmerman, de Koning, van der Horn, Scheenen, Jacobs, Hageman, Saykin, et al., 2017). However, none of these identified predictors reflect the mechanistic process affected by mTBI. Identification of the aberrant neural processes underlying a disorder may be a more fruitful target for diagnosis, prognosis and target engagement than phenotypic characterization (Gillan & Daw, 2016; Insel et al., 2010; Montague, Dolan, Friston, & Dayan, 2012). This mechanistic approach may ultimately reveal if the “miserable minority” of individuals with prolonged PPCS (Ruff, 2005) can be characterized by damage to functional neural systems, or if prolonged symptoms areunrelated to any potential brain damage (Rohling et al., 2012).

Many neural signals reflect domain-general processes with common sensitivity to executive function, mood, and effort (Cavanagh & Shackman, 2014; Chang, Yarkoni, Khaw, & Sanfey, 2013; De La Vega, Chang, Banich, Wager, & Yarkoni, 2016; Roy, Shohamy, & Wager, 2012; Shackman et al., 2011), making them promising candidate biomarkers of PPCS. An often-overlooked approach to quantifying disease-specific neurological deficits is offered by event-related electroencephalographic (EEG) responses. EEG is uniquely sensitive to canonical neural operations which underlie emergent psychological constructs (Cavanagh, 2019; Fries, 2009; Siegel, Donner, & Engel, 2012), making it well suited for discovery of aberrant neural mechanisms that underlie complicated disease states (Insel et al., 2010; Montague et al., 2012). At a local scale, event-related field potentials can be interpreted as “spectral fingerprints” of computations implemented by neuronal circuits (Siegel et al., 2012). At the level of the human scalp, EEG potentials reflect the common summated fingerprints of primitive cognitive processes (Buzsáki. Logothetis, & Singer, 2013), providing a direct link between brain function and cognitive states. Prior studies of EEG in the study of mTBI largely fall into two distinct approaches, neither of which has thus far identified aberrant mechanisms or offered compelling prognosis of PPCS.

The most common approach for studying EEG features in mTBI is the Quantitative EEG (QEEG) approach, which assesses a few minutes of resting EEG data and applies Fourier-based derivations to populate large scale normative datasets, in order to contrast with patient-specific databases. QEEG measures are maximally sensitive to more severe cases of injury (Ayaz et al., 2015; Hanley, Prichep, Badjatia, et al., 2017; Hanley, Prichep, Bazarian, et al., 2017; Hanley et al., 2013; Naunheim, Treaster, English, Casner, & Chabot, 2010; Prichep et al., 2014; Prichep, Naunheim, Bazarian, Mould, & Hanley, 2015; Thatcher et al., 2001), and while the information provided for more mild and moderate cases is discriminating (Barr, Prichep, Chabot, Powell, & McCrea, 2012; McCrea, Prichep, Powell, Chabot, & Barr, 2010; Prichep, McCrea, Barr, Powell, & Chabot, 2013) it does not reveal any generalizable features or abnormal mechanisms of brain functioning. When the distinguishing EEG features are reported, they vary between studies (Haneef, Levin, Frost, & Mizrahi, 2013; McCrea et al., 2010; Nuwer, Hovda, Schrader, & Vespa, 2005; Thatcher et al., 2001; Thatcher, Walker, Gerson, & Geisler, 1989), and even within studies depending on analytic techniques (Prichep et al., 2014). In sum, while QEEG procedures are promising within certain areas such as hematoma detection, this approach has limited ability to understand or predict PPCS (see: Arciniegas, 2011).

The other common EEG-centered approach to understanding mTBI utilizes event-related potentials (ERPs) or short-latency evoked potentials to quantify changes in information processing. In severe TBI, many studies have observed diminished short-latency sensory (Arciniegas et al., 2001) and longer-latency cognitive ERP features (Larson, Fair, Farrer, & Perlstein, 2011; Lew, Poole, Castaneda, Salerno, & Gray, 2006). In mTBI, evidence is mixed for aberrant short-latency ERP features (Broglio, Moore, & Hillman, 2011; Folmer, Billings, Diedesch-Rouse, Gallun, & Lew, 2011; Kraus et al., 2016; Rapp et al., 2015) but many studies reliably observe differences in longer-latency cognitive ERP features (Dupuis, Johnston, Lavoie, Lepore, & Lassonde, 2000; Folmer et al., 2011; Larson, Farrer, & Clayson, 2011; Lavoie, Johnston, Leclerc, Lassonde, & Dupuis, 2004; Moore, Hillman, & Broglio, 2014; Weinberg, 2000; Wilson, Harkrider, & King, 2014). While this is promising, the majority of these studies tested individuals in the chronic injury stage, and/or combined patients across the TBI severity spectrum (i.e., mild and severe patients: Bailey et al., 2015; Doi, Morita, Shigemori, Tokutomi, & Maeda, 2007; Dupuis et al., 2000; Gilmore, Marquardt, Kang, & Sponheim, 2018; Larson, Fair, et al., 2011; Lavoie et al., 2004; Moore et al., 2014; Shah et al., 2017; Weinberg, 2000). The sample characteristics of these studies severely limit the ability to draw generalizable conclusions about how mTBI alters neural processes during the sub-acute period, and how neural processes may recover in the first few months post-injury.

One consistent finding from ERP studies is a diminished P3b component in individuals with a history of TBI (Broglio et al., 2011; Brush, Ehmann, Olson, Bixby, & Alderman, 2017; Duncan, Summers, Perla, Coburn, & Mirsky, 2011; Gomes & Damborska, 2017; Lavoie et al., 2004; Moore et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2014); this diminishment appears to correlate with PPCS (Dupuis et al., 2000; Lavoie et al., 2004). The P3b is elicited with an “oddball” paradigm where a participant is required to identify a rare stimulus in a sequence of temporally discrete common stimuli (i.e. “beep-beep-beep-boop”). The P3b is thought to reflect the top-down accumulation of evidence leading to cognitive categorization and context updating (Donchin, 1981; Duncan-Johnson & Donchin, 1977; Johnson, 1986; Polich & Kok, 1995; Twomey, Murphy, Kelly, & O’Connell, 2015). The simplicity of the oddball task, the depth of knowledge of the P3b component, and the suggestive prior literature combine to form a compelling rationale for utilizing the oddball task as a probe of generic cognitive functioning in mTBI. However, a variant of the common oddball task may provide additional, unique information on the dysfunction observed following acute mTBI. Whereas the P3b is maximal over parietal cortex, a different component known as the P3a is maximal over the vertex and frontal midline and is more closely tied to obligatory bottom-up orienting responses (Polich, 2007; Seer, Lange, Georgiev, Jahanshahi, & Kopp, 2016).

The P3a is elicited with novel distractor stimuli embedded in the stimulus sequence (e.g. a dog bark randomly embedded in the auditory stream of pure tones described above) and is thought to reflect the operations of the central nervous system orienting response (Barceló, Periáñez, & Knight, 2002; Friedman, Cycowicz, & Gaeta, 2001; Nieuwenhuis, De Geus, & Aston-Jones, 2011). This specific aspect of the orienting response is thought to act as an alarm bell of the need for cognitive control, helping to trigger the cascade of brain processes involved in adjusting to new demands (Barcelo, Escera, Corral, & Periáñez, 2006; Cavanagh, Zambrano-Vazquez, & Allen, 2012; Kopp, Tabeling, Moschner, & Wessel, 2006; Wessel, 2018; Wienke, Basar-Eroglu, Schmiedt-Fehr, & Mathes, 2018). Convergent with this orienting role, P3a appears to reflect the operations of midcingulate and salience-related areas like the operculum, whereas the primary generators of the P3b are posterior temporo-parietal junction and dorsolateral frontal cortex (Linden, 2005; Polich, 2007; Soltani & Knight, 2000). The literature is unclear on the sensitivity of P3a vs. P3b to trauma in mTBI patients (Broglio et al., 2011; Witt, Lovejoy, Pearlson, & Stevens, 2010), but one study has observed that NoGo EEG activities closely related to the P3a orienting response (see: Barry & Rushby, 2006; Waller, Hazeltine, & Wessel, 2019) are diminished following mTBI and normalize over time, in line with changes in symptoms (Candrian et al., 2018).

In the current investigation, we aimed to identify how the P3a and P3b components were differentially affected in sub-acute, typically-recovering mTBI versus more severe patients who failed to recover from their injury (Broglio et al., 2011; Brush et al., 2017; Duncan et al., 2011; Gomes & Damborská, 2017; Lavoie et al., 2004; Moore et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2014). We hypothesized that the P3a would be diminished in sub-acute mTBI, that it would scale with the degree of cognitive symptoms, and that it would predict recovery from cognitive symptoms at a later time point. We contrasted these expected findings for sub-acute mTBI to a group of more chronic patients, whom we expected to show diminished P3b in line with previous literature. We did not have any specific hypotheses about the role of the P3b in sub-acute mTBI, or of the P3a in participants with chronic brain injury. If these novel hypotheses about the role of the P3a in sub-acute mTBI were verified, it would identify a dysfunction in a primitive neural process that underlies cognitive control, preparing the way for a more comprehensive characterization of mechanistic deficits following brain injury.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

The University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (UNMHSC) Human Research Protections Office approved the study and all participants provided written informed consent. All participants were aged 18-55, were fluent in English, had no premorbid major medical or psychiatric conditions, no current or previous history of substance abuse, and were not currently taking medications that alter cognitive functioning, with the exception of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. In total, 4 participants with mTBI and 3 control participants were taking SSRIs.

Sub-acute mTBI patients were consecutively recruited from the Departments of Neurosurgery and Emergency Medicine from UNMHSC within two weeks following their injury in this prospective cohort design. Participants from the sub-acute TBI group had a Glasgow Coma Scale of 13-15 if available, and had experienced a loss of consciousness (≤ 30 minutes) following injury. Injury history was assessed with a modified version of the Rivermead semi-structured interview (King, Crawford, Wenden, Moss, & Wade, 1995; Mayer et al., 2018). Although the Rivermead also contains somatic symptom ratings, those are not examined here since control participants did not complete this assessment. Control participants included sex- and age-matched individuals from the Albuquerque, New Mexico community. None of the sub-acute mTBI or control participants had a previous head injury.

Sub-acute mTBI and control participants were invited to three assessment sessions. Session 1 was from 3-14 days post-injury. Session 2 was ~2 months (1.5 to 3) and Session 3 was ~4 months (3 to 5) following Session 1. Participants were paid $20, $25, or $30/hr for participation in each respective session. Chronic TBI participants were taken from a parallel treatment study and we only report on their first (pre-treatment) session here. All chronic patients had experienced a loss of consciousness (less than 24 hours), had a Glasgow Coma Scale of 9-15, had less than one week of post-traumatic amnesia, endorsed at least one ongoing cognitive symptom on the Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory (NSI), and had been on stable doses of any psychotropic medication for the past two months. Many chronic patients endorsed more than one TBI (15/23 endorsed at least one prior TBI); information on the most recent TBI is detailed here. Since the most recent TBI varied in severity (6 moderate, 17 mild), we termed these chronic individuals mild and moderate TBI (chronic mmTBI).

2.2. Questionnaires and Neuropsychological Assessments

All participants completed demographic and neuropsychological assessments in their first session only. Symptom-related questionnaires were administered in each session (see Figure 1), including the NSI, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and the Frontal Systems Behavior scale (FrSBe). Only participants who scored above 45 on the test of memory malingering (TOMM) are reported here (only one chronic mmTBI participant was removed). Other assessments included the Test of Premorbid Functioning (TOPF), the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS IV) digit span and coding, the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R). These values are shown in Table 1. Table 2 details the injury characteristics of the sub-acute and chronic injury groups. Table 1 also details the number of participants that completed each assessment session. While the control group had relatively stable enrollment, the sub-acute mTBI group suffered from attrition, with about ¾ of the original cohort of participants returning for session 2 and about ½ returning for session 3. Due to this high attrition at the third time point, we only report on the first two sessions here. All data, including those from the third time point, are available online (see Data Availability section). We investigated factors contributing to attrition using logistic regression and non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests on all session 1 variables reported in Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 1; details are reported in the Results.

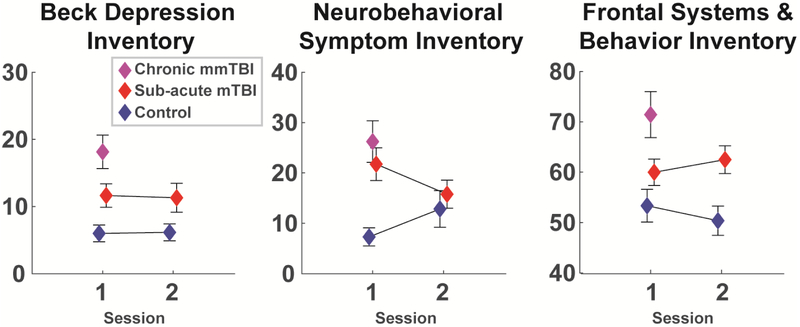

Figure 1. Responses to symptom questionnaires for each group and each session.

The chronic group was only assessed once. Data are mean +\− SEM.

Table 1.

Sample size, demographics, and neuropsychological test scores for all groups. These neuropsychological data were only collected at the first session. All data are mean +/− SD except for session counts. n/a = not applicable. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences from controls: *p<.05, **p<.01.

| Control | Sub-Acute mTBI | Chronic mmTBI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1: N (female) | 24 (11) | 38 (12) | 23 (10) |

| Session 2: N (female) | 23 (10) | 30 (8) | n/a |

| Age | 30.29 (11.65) | 26.74 (8.4) | 36.22 (11.23) |

| Yrs Ed | 15.08 (2.45) | 13.26 (2.05) ** | 15.09 (2.57) |

| TOPF | 106.41 (13.12) | 94.78 (15.25) ** | 103.83 (16.38) |

| WAIS Coding | 10.77 (2.54) | 9.08 (2.69) * | 10.04 (3.34) |

| WAIS Span | 11.14 (2.55) | 9.79 (2.63) | 9.96 (3.86) |

| HVLT-R Trials 1-3 | 9.02 (1.35) | 7.65 (1.50)** | 8.32 (1.86) |

| HVLT-R Delay Recall | 50.77 (9.08) | 37.58 (11.71)** | 41.96 (11.70)** |

Table 2.

Injury information for TBI groups. Data are presented as counts (GCS, LOM), median +/− intra-quartile range (LOC minutes, Time since injury), or rounded percentages. For chronic patients these descriptors are for their most recent injury. Any LOC described as “less than a minute” was coded as .5 minutes. n/a = not applicable (not gathered or reported). GCS=Glasgow Coma Scale, LOC=loss of consciousness, LOM=loss of memory (yes/no question), IED=improvised explosive device.

| Sub-Acute mTBI | Chronic mmTBI | |

|---|---|---|

| GCS 13-15 | 13 (2), 14 (1), 15 (26), n/a (9) | n/a |

| LOC Minutes | 5 (6.38) | 5 (9.5) |

| LOM | Yes (21), No (17) | Yes (15), No (8) |

| Time Since Injury | 10 (5) days | 2 (3) years |

| Accident | 3% | 9% |

| Assault | 18% | 22% |

| Fall | 11% | 9% |

| Motor Vehicle | 53% | 17% |

| Sport | 16% | 35% |

| IED | 0% | 9% |

2.3. Auditory Oddball Task

The 3-stimulus auditory oddball task was programmed in Matlab using Psychtoolbox. Standards were 440Hz sinusoidal tones (70% of trials), targets were 660 Hz sinusoidal tones (15% of trials) and novel distractors (15% of trials) were unique sections from a naturalistic sounds dataset (Bradley & Lang, 1999). All sounds were presented for 200 ms, tones were presented at 80 dB and naturalistic novel sounds had a mean of 65 dB with an inter-quartile range of +/− 6.5 dB. A random inter-trial-interval was selected from a uniform distribution of 1000 to 1500 ms. Sounds were played on stereo speakers. Participants were instructed to count the targets (“high tones”) and ignore standards (“low tones”) and novels (“weird tones”). This paradigm removes potential confounding influences of motor system activity and decision making on P3 amplitudes (Johnson, 1986; O’Connell, Dockree, & Kelly, 2012). Participants completed 260 trials (184 standard, 38 targets, 38 novel) with a rest break between blocks. Including instructions, the task took about 16 minutes to complete.

2.4. EEG Recording and Preprocessing

EEG was recorded continuously from sintered Ag/AgCl electrodes across .1 to 100 Hz with a sampling rate of 500 Hz, an online CPz reference, and a ground at AFz on a 64 channel Brain Vision system. The vertical electrooculogram (VEOG) was recorded from bipolar auxiliary inputs. Data were epoched around the stimulus onset (−2000 to 2000 ms), from which the associated stimulus responses were isolated. Activity at the reference electrode CPz was re-created via re-referencing. Four ventral temporal sites near the ears were then removed (two from each hemisphere), as these tend to be unreliable, leaving 60 electrodes. Bad channels and bad epochs were identified using a conjunction of the FASTER algorithm (Nolan, Whelan, & Reilly, 2010) and pop_rejchan from EEGlab (Delorme & Makeig, 2004) and were subsequently interpolated and rejected respectively. Data were then re-referenced to an average reference. Eye blinks were removed following independent components analysis in EEGlab (Delorme & Makeig, 2004). Single trial EEG epochs were filtered from .1 to 20 Hz then baseline corrected from −200 to 0 ms pre-stimulus. There were no significant group differences in the number of oddball targets reported or in the number of clean EEG epochs included in the ERPs (Supplemental Figure S1). Since the hypotheses for this study were based on existing literature, we also used a single electrode to define each ERP component. Components were quantified over the grand average across all data points, which is orthogonal to any hypothesis tests (see Figure 2). The P3a was defined as the average amplitude from 300 to 450 ms at FCz in the novelty condition, and the P3b was defined as the average amplitude from 400 to 700 ms at the Pz electrode in the target condition. Supplemental Figures S2 and S3 show all ERPs split by group and condition.

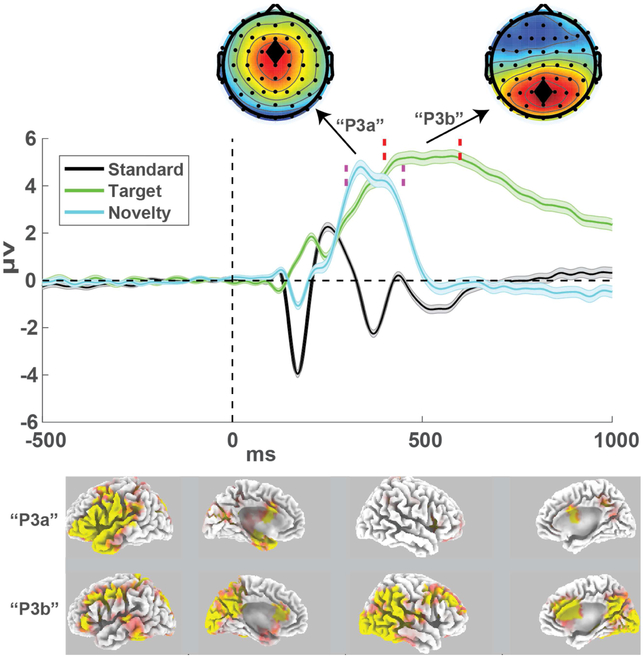

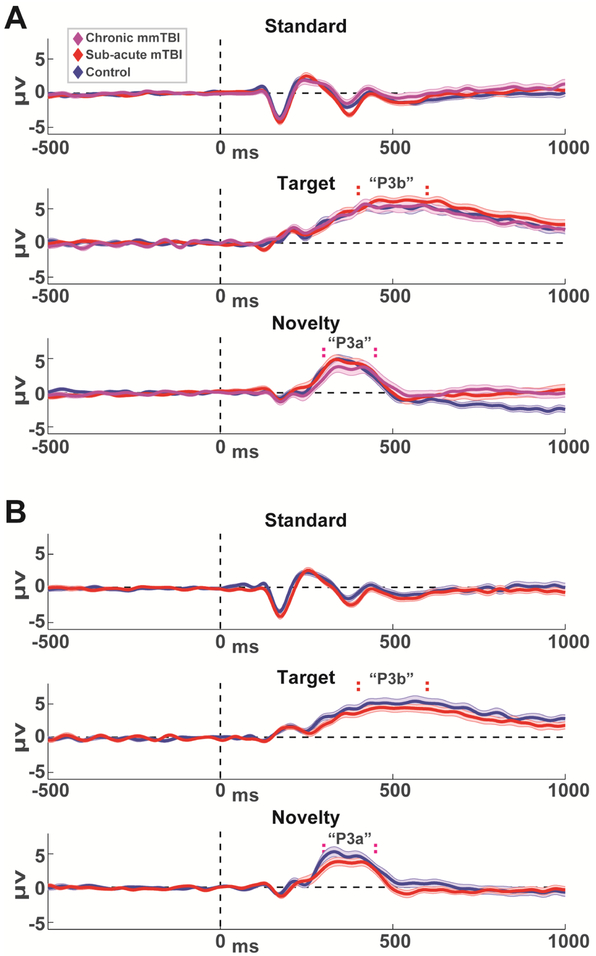

Figure 2. Grand average event-related potentials collapsed over all participants and sessions.

The P3a was defined within the time window shown in the dashed magenta lines (300-450 ms) at the fronto-central FCz electrode. The P3b was defined within the time window shown in the dashed red lines (400-700 ms) at the parietal Pz electrode. ERPs are mean +\− SEM. sLORETA source estimations show the t-test output of these time windows as contrasted to the standard condition. P3a estimates were scaled +/− 10 and P3b estimates were scaled +/− 15.

2.5. Source Estimation

The sLORETA toolbox was used for source estimation of these ERP time windows (Pascual-Marqui, 2002). The sLORETA package uses minimum norm estimation to estimate the smoothest, or lowest estimation error, to voxels restricted to cortical tissue. The windows for novelty and target conditions were contrasted to the average over the 300 to 450 ms window in the standard condition. Subject-wise normalization was used for all contrasts and the non-parametric statistical package was used to test the outcomes vs. 5000 permutations. Cortical maps show t-test outputs.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Independent t-tests were used to compare questionnaire and ERP data from the chronic group with the control group. The analysis of change over time between the control and sub-acute groups utilized mixed linear models (MLMs) to account for individual change within each group in the context of missing data (e.g. attrition). MLMs used restricted maximum likelihood estimation with fixed effects for group (binary), session (continuous), and the group*session interaction. Session was modeled as a repeated factor with autoregressive covariance.

To investigate relationships between ERP activity and symptoms, non-parametric Spearman’s rho tests were used for zero-order correlations within each group and rho-to-z transformed coefficients were used to contrast correlation coefficients between groups with a z-test. To contrast correlations within groups, Meng’s z-test for correlated coefficients was used (Meng, Rosenthal, & Rubin, 1992). For all symptom-related analyses, only the FrSBe was investigated. Among measures included in this study, the FrSBe is the only scale related to the executive functions putatively reflected by P3a or P3b processes: the specificity of the BDI to depression and high reliance of the NSI to somatic distress are divergent from the executive constructs measured here. The FrSBE score is scaled by the age, sex, and years of education of the participant (Grace & Malloy, 2001), making it well-suited for zero-order correlation with brain variables within this diverse sample. Reliabilities of FrSBe, P3b and P3a (Table 3) were assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) within a two-way mixed effects model defined by absolute agreement (Koo & Li, 2016). These analyses were performed separately for each group.

Table 3.

Test-retest reliability of measures using intraclass correlation coefficients. FrSBe = Frontal Systems and Behavior Inventory.

| Control | mTBI | |

|---|---|---|

| FrSBe | .78 | .69 |

| P3b | .78 | .72 |

| P3a | .79 | .74 |

The degree of an individual’s symptomatic recovery was defined as the change over time in FrSBe score (session 2 minus session 1; lower scores thus mean reduced symptoms over time). Hierarchical multiple regression was used to examine the ability of brain-based measures (P3a & P3b) to predict change in FrSBe score when accounting for demographic variables (age, sex, TOPF).

3. Results

Both logistic regression and non-parametric rank-sum tests revealed that lower WAIS digit span in session 1 significantly predicted attrition in the sub-acute mTBI group in session 2. This finding is addressed in the discussion. Source estimation (Fig 2) demonstrates how novelty and target conditions elicit partially overlapping, yet distinct cortical networks. Midcingulate and left opercular areas were particularly active in the novelty condition whereas right temporo-parietal junction and medial frontal cortex were involved in target responding. Next we examined if the scalp-recorded P3a and P3b reflected independent markers of cognitive function. P3a and P3b amplitudes were uncorrelated with each other within each group and session (CTL: S1 rho(22)=.05, p=.82; S2 rho(21)=.12, p=..58; sub-acute mTBI: S1 rho(36)=.19, p=.82; S2 rho(28)=.09, p=.62; chronic mmTBI: S1 rho(21)=−.07, p=.76). Test-retest reliabilities were good, and similar between FrSBe and P3 measures.

3.1. Group Differences

In line with expectations, groups differed on symptomatic assessments. MLMs revealed main effects between control and sub-acute groups for all symptom variables, with group main effects for BDI (F(1,63.23)=5.59, p=.02) and FrSBe (F(1,62.59)=5.78, p=.02) but no group * session interactions (Fs<1). NSI had both a group main effect (F(1,60.88)=5.34, p=.02) and group * session interaction (F(1,45.75)=4.59, p=.04), where the groups were different in session 1 but not session 2 (See Fig 1). The mmTBI group (again, assessed in session 1 only) differed from controls in symptomatic questionnaires (BDI, NSI & FrSBe: ts>3.2, ps<.01). The sub-acute and chronic groups also differed on some measures (BDI & FrSBe ts>2.2, ps<.05).

Contrary to expectations, groups did not differ on P3a or P3b amplitudes. The mmTBI group was indistinguishable from the control and the sub-acute groups (all ts<1). MLMs did not reveal any main effects for P3b or P3a amplitudes between the control and the sub-acute group (Fs<1), nor any interactions (P3a: F(1,53.38)=1.96, p=.17; P3b: F(1,47.71)=3.10, p=.09). In sum, symptoms were different between groups yet brain responses were not, failing to support our hypotheses at the group level of diminished P3a for sub-acute mTBI and/or diminished P3b for chronic mmTBI.

3.2. Individual Differences

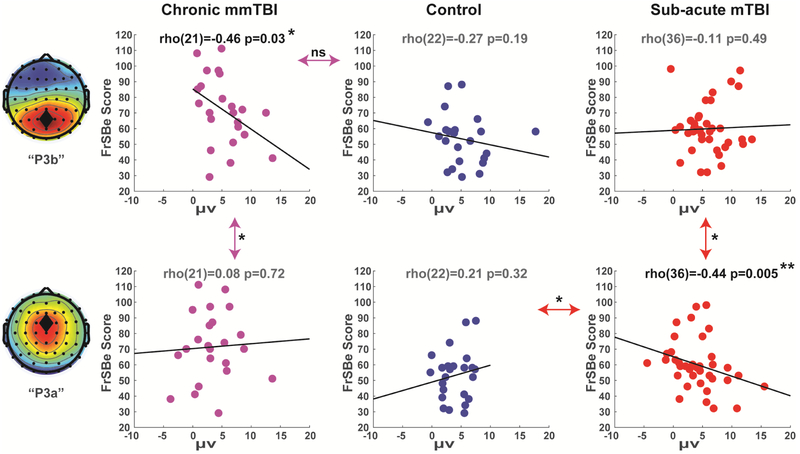

Next we investigated individual differences within groups (Fig 4). In the chronic mmTBI group, the correlation between FrSBe and P3b was significant and negative (rho(21)=−.46, p=.03). This relationship for the chronic group did not differ significantly from the corresponding (nonsignificant) correlation between FrSBe and P3b within the control group (rho(22)=−.27, p=.19; z=.71, p=.48), but did differ significantly from the chronic group's own (nonsignificant) correlation between FrSBe and the P3a (rho(21)=.08, p=.72; Meng’s z=1.73, p=.04). These findings were partially supportive of our hypothesis that P3b would capture variance associated with symptomatology due to mmTBI.

Figure 4. Correlations between ERP variables and FrSBe symptoms in session 1.

Only the chronic group had a significant correlation between symptoms and P3b amplitude. Only the sub-acute group had a significant correlation between symptoms and P3a amplitude. Double arrows indicate the comparison of slopes between or within groups. ns=not significant, *p<.05, **p<.01.

In the sub-acute group session 1, the correlation between FrSBe and P3a was significant and negative (rho(36)=−.44, p=.005). This relationship for the sub-acute group was significantly different from the corresponding (nonsignificant) correlation between FrSBe and P3a within the control group (rho(22)=.15, p=.32; z=2.26, p=.02), and from the sub-acute group's own (nonsignificant) correlation between FrSBe and P3b (rho(36)=−.11, p=.49; Meng’s z=1.66, p=.048).

In session 2, the correlation between FrSBe and P3a was significant and negative again in the sub-acute group (rho(28)=−.49, p=.006) which was significantly different from the (nonsignificant) correlation between FrSBe and P3a in the control group (rho(21)=. 27, p=.20; z=2.76, p=.006) and nearly significantly different from the sub-acute group's own (nonsignificant) correlation between FrSBe and P3b (rho(28)=−.11, p=.55; Meng’s z=1.59, p=.06), see Supplemental Figure S3. These findings were supportive of our hypothesis that P3a would scale with the degree of cognitive symptoms following sub-acute mTBI, and they revealed specific variance in P3a versus P3b amplitudes as a function of individual differences in sub-acute vs. chronic PPCS.

3.3. Predicting Individual Symptom Recovery

Finally, we examined if brain-based measures could predict change over time in FrSBe symptomatology in the sub-acute group. Change in FrSBe symptomatology between the first and second sessions (session 2 minus session 1) was not significantly predicted by demographic variables including age (rho(26)=−.23, p=.24), TOPF (rho(25)=−13, p=.51), or sex (t(1,26)=0.61, p=.55), nor was it predicted by the variable related to participant dropout (WAIS digit span: rho(26)=−.11, p=.58).

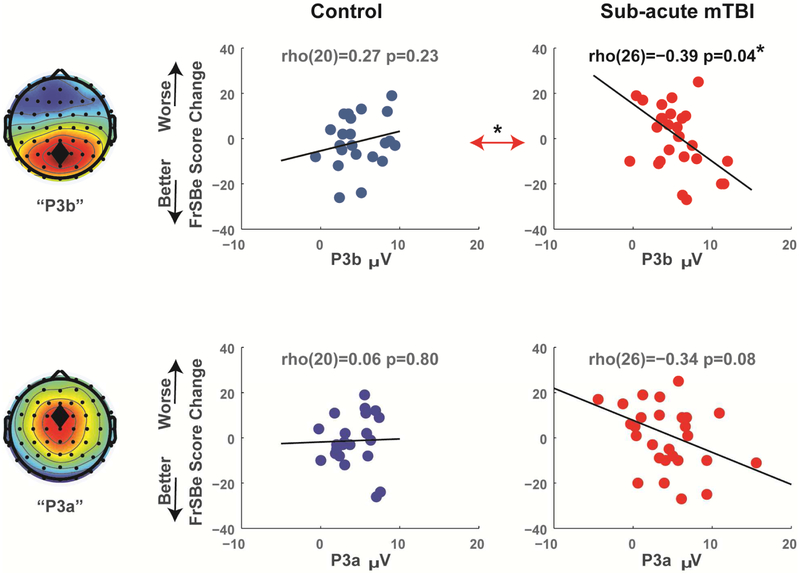

In a multiple regression model, session 1 P3a and P3b together accounted for 31% of the variance in FrSBe change (F(2,25)=5.645, p=.009), but only P3b had a significant beta weight (t=2.58, p=.02, partial R2=.21) not P3a (t=1.74, p=.10, partial R2=.11). These individual patterns can be seen in Figure 5. Session 1 P3b amplitude had a significant negative correlation with FrSBe change in the sub-acute group (rho(26)=−.39, p=.04) which was significantly different from the corresponding positive correlation for controls (rho(20)=.27, p=.23; z=2.26, p=.02). The correlation between session 1 P3a amplitude and FrSBe change in the sub-acute group was not significant (rho(26)=−.34, p=.08), nor was it significantly different from the corresponding correlation for controls (rho(20)=.06, p=.80; z=1.36, p=.80).

Figure 5. Correlations between ERP variables at session 1 and FrSBe symptom change (session 2 minus session 1).

Only the P3b predicted significant variance in FrSBe recovery in the sub-acute group. While P3a had a compelling trend, it remained a non-significant predictor of recovery in all statistical models. Double arrows indicate the comparison of slopes between groups. *p<.05.

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to test the independent predictive power of P3a and P3b on FrSBe change above and beyond demographic predictors. In the first level, age, sex, and TOPF accounted for 14% of the variance in FrSBe change, but this was non-significant (F(3,23)=1.26, p=.31). Even when P3a was added to the first level the model was not significant (F(4,22)=1.71, p=.18, R2=.24). When P3b was added to the second level, it was a significant addition (F(1,21)=6.19, p=.02) and accounted for an additional 17% of the variance in FrSBe change. This full model was significant (F(5,21)=2.93, p=.04, R2=.41), and only P3b had a significant beta weight (t=2.49, p=.02) not P3a (t=2.01, p=.06) nor the other variables. In sum, while P3a may be an important feature of cognitive symptoms following sub-acute mTBI (see Figure 4), P3b accounts for a significant amount of unique variance in cognitive recovery, above and beyond P3a and the demographic variables.

4. Discussion

In this report we demonstrated that a simple and rapid assessment of neural activity is sensitive to individual differences in sub-acute mTBI symptomatology and predicts recovery within a 2 month time span. These findings were specific to TBI groups and they outperformed demographic predictors of recovery. Session 1-specific effects were doubly dissociated between sub-acute and chronic TBI patients, with symptoms correlating with P3a in the sub-acute group but with P3b in the chronic group. Interestingly, P3b (not P3a) amplitude was the best predictor of symptom recovery over time in the sub-acute group. These findings suggest that EEG-based neural markers represent a largely untapped resource for understanding the consequences of brain injury.

The finding that higher symptoms correlated with lower P3b amplitude in chronic TBI patients is consistent with prior findings, although we observed this effect only as a within-group effect in chronic TBI participants and not as a difference between chronic TBI and control groups. A diminished P3b is observed in many cases of psychiatric and neurological distress, including dementia (Cecchi et al., 2015), psychopathy (Anderson, Steele, Maurer, Bernat, & Kiehl, 2015), and substance abuse (Iacono, Malone, & McGue, 2003). When considered with the chronic mmTBI patient findings reported here and elsewhere (Broglio et al., 2011; Brush et al., 2017; Doi et al., 2007; Duncan et al., 2011; Gilmore et al., 2018; Gomes & Damborská, 2017; Lavoie et al., 2004; Moore et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2014), a smaller P3b amplitude may reflect a generic decrement in cognitive abilities common amongst varied forms of distress. Although the chronic mmTBI group reported here combined patients across the TBI severity spectrum and recovery timeline, this sample is representative of of the sample characteristics of many prior ERP studies of TBI. Given the differences between TBI groups reported here, the chronic group shouldn’t be used to infer how acute trauma becomes compromised. Rather, these groups should be understood as a contrast between two common yet very different populations within the family of TBIs.

The specificity of the inverse relationship between FrSBe symptoms and P3a amplitude to the sub-acute group is notable for three reasons. First, this effect was dissociated from the patterns observed in the chronic mmTBI group. Second, this effect relationship was replicated in session 2. Finally, as a reflection of the orienting response that can trigger the need for cognitive control, the P3a was proposed to be particularly sensitive to executive dysfunction. A diminished P3a has been observed in patient groups with significant frontal dysfunction like in Parkinson’s disease (Seer et al., 2016; Solís-Vivanco et al., 2015). The fact that these brain-symptom correlations were absent among chronic mmTBI suggests that P3a may index short-term executive problems following mTBI.

Although P3a amplitude was specifically related to short-term executive dysfunction, P3b amplitude was the best predictor of FrSBe recovery. Since P3b was not different between groups and did not scale with symptomatology, it is unknown if a smaller P3b is a complex expression of mTBI symptomatology or if it reflects a latent risk factor. Pre-existing individual differences partially reflected by P3b amplitude may be the best predictors of injury recovery. This possibility does not diminish the utility of P3b measurements (indeed, it still predicted unique variance above and beyond demographic predictors), but it qualifies the interpretation and limits the generalizability. Fortunately, these are testable hypotheses. Future experiments may aim to use more complex tasks to understand how acute mTBI affects evidence accumulation and decision making in order to better link online executive processes to future symptom recovery.

4.1. Limitations

The first limitation of these findings is the modest sample size in each group. A larger control group would provide more stable estimates of reliability. Attrition between the initial assessment and the 4 month follow-up in the sub-acute mTBI group led to its omission from this report. While digit span did significantly predict attrition between the first and second session for the sub-acute mTBI group, we do not think this is an important predictor of symptom change in the returning participants. Considering the number of uncorrected statistical tests (14 predictors from Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 1), the small sample (attrition was only 8 participants), and the lack of correlation between span and recovery, there is little that can be inferred about the prognostic power of this variable.

4.2. Conclusions

These findings identified symptom-specific alterations in neural systems that vary along the time course of post-concussive symptomatology. The prognostic power of these findings above standard demographic predictors suggests utility as a potential biomarker for PPCS trajectory. Since most large hospitals already have ample capabilities for assessing EEG, the application of simple EEG-based task reactivity may have promising biomedical utility for addressing a range of TBI consequences.

Data Availability:

All data and code for this experiment are available on the PRED+CT website: www.predictsite.com; Accession #d009.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3. Grand average event-related potentials for each group and session.

Standards and Novelty are from FCz, Targets are from Pz. P3b and P3a time windows are indicated by vertical dashed lines. A) Session 1. B) Session 2. ERPs are mean +\− SEM.

Executive symptoms in chronic TBI participants related to a smaller P3b

Conversely, executive symptoms in sub-acute TBI participants related to a smaller P3a

This relationship in sub-acute TBI participants was replicated 2 months later

P3b predicted independent variance in sub-acute symptom recovery over this time period

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research is supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20GM109089.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: None of the authors have potential conflicts of interest to be disclosed.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson NE, Steele VR, Maurer JM, Bernat EM, & Kiehl KA (2015). Psychopathy, attention, and oddball target detection: New insights from PCL-R facet scores. Psychophysiology, 52(9), 1194–1204. 10.1111/psyp.12441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arciniegas DB (2011). Clinical electrophysiologic assessments and mild traumatic brain injury: State-of-the-science and implications for clinical practice. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 82(1, 41–52. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arciniegas DB, Topkoff JL, Rojas DC, Sheeder J, Teale P, Young DA, …Adler LE (2001). Reduced hippocampal volume in association with p50 nonsuppression following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neuropsychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences, 13(2), 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz SI, Thomas C, Kulek A, Tolomello R, Mika V, Robinson D,… O’Neil BJ (2015). Comparison of quantitative EEG to current clinical decision rules for head CT use in acute mild traumatic brain injury in the ED. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 33(4), 493–496. 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey NW, Hoy KE, Maller JJ, Upton DJ, Segrave RA, Fitzgibbon BM, & Fitzgerald PB (2015). Neural evidence that conscious awareness of errors is reduced in depression following a traumatic brain injury. Biological Psychology, 106, 1–10. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcelo F, Escera C, Corral MJ, & Periáñez JA (2006). Task switching and novelty processing activate a common neural network for cognitive control. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 18(10), 1734–1748. 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.10.1734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barceló F, Periáñnez J. a, & Knight RT (2002). Think differently: a brain orienting response to task novelty. Neuroreport, 13(15), 1887–1892. 10.1097/00001756-200210280-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr WB, Prichep LS, Chabot R, Powell MR, & McCrea M (2012). Measuring brain electrical activity to track recovery from sport-related concussion. Brain Injury, 26(1), 58–66. 10.3109/02699052.2011.608216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry RJ, & Rushby JA (2006). An orienting re X ex perspective on anteriorisation of the P3 of the event-related potential, 539–545. 10.1007/s00221-006-0590-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigler ED (2008). Neuropsychology and clinical neuroscience of persistent post-concussive syndrome. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS, 14(1), 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, & Lang PJ (1999). International affective digitized sounds (IADS): Stimuli, instruction manual and affective ratings. Tech. Rep. No. B-2 Gainesville, FL: The Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Broglio SP, Moore RD, & Hillman CH (2011). A history of sport-related concussion on event-related brain potential correlates of cognition. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 82(1, 16–23. http://doi.Org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brush CJ, Ehmann PJ, Olson RL, Bixby WR, & Alderman BL (2017). Do sport-related concussions result in long-term cognitive impairment? A review of event-related potential research. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G, Logothetis N, & Singer W (2013). Scaling Brain Size, Keeping Timing: Evolutionary Preservation of Brain Rhythms. Neuron, 80(3), 751–764. http://doi.org/10.1016Zj.neuron.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candrian G, Müller A, Dall’Acqua P, Kompatsiari K, Baschera GM, Mica L, & Johannes S (2018). Longitudinal study of a NoGo-P3 event-related potential component following mild traumatic brain injury in adults. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 61(1), 18–26. 10.1016/j.rehab.2017.07.246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh JF (2019). Electrophysiology as a theoretical and methodological hub for the neural sciences, (November 2018), 1–13. 10.1111/psyp.13314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh JF, & Shackman AJAJ (2014). Frontal Midline Theta Reflects Anxiety and Cognitive Control: Meta-Analytic Evidence. Journal of Physiology, Paris, 109(1–3), 3–15. 10.1016/jjphysparis.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh JF, Zambrano-Vazquez L, & Allen JJJBB (2012). Theta lingua franca: a common mid-frontal substrate for action monitoring processes. Psychophysiology, 49(2), 220–38. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01293.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchi M, Moore DK, Sadowsky CH, Solomon PR, Doraiswamy PM, Smith CD, … Fadem KC (2015). A clinical trial to validate event-related potential markers of Alzheimer’s disease in outpatient settings. Alzheimer’s and Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment and Disease Monitoring, 1(4), 387–394. 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LJ, Yarkoni T, Khaw MW, & Sanfey AG (2013). Decoding the Role of the Insula in Human Cognition: Functional Parcellation and Large-Scale Reverse Inference. Cerebral Cortex, 23(3, 739–749. 10.1093/cercor/bhs065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Vega A, Chang LJ, Banich MT, Wager TD, & Yarkoni T (2016). Large-Scale Meta-Analysis of Human Medial Frontal Cortex Reveals Tripartite Functional Organization. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4402-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorme A, & Makeig S (2004). EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J Neurosci Methods, 134(1), 9–21. 10.1016/jjneumeth.2003.10.009S0165027003003479 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi R, Morita K, Shigemori M, Tokutomi T, & Maeda H (2007). Characteristics of cognitive function in patients after traumatic brain injury assessed by visual and auditory event-related potentials. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 86(8), 641–649. 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318115aca9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donchin E (1981). Surprise!…Surprise? Psychophysiology, 18(5, 493–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan-Johnson CC, & Donchin E (1977). On quantifying surprise: the variation of event-related potentials with subjective probability. Psychophysiology, 14(5), 456–67. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/905483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan CC, Summers AC, Perla EJ, Coburn KL, & Mirsky AF (2011). Evaluation of traumatic brain injury: Brain potentials in diagnosis, function, and prognosis. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 82(1), 24–40. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis F, Johnston KM, Lavoie M, Lepore F, & Lassonde M (2000). Concussions in athletes produce brain dysfunction as revealed by event-related potentials. Clinical Neuroscience and Neuropathology, 11(18), 4087–4092. 10.1097/00001756-200012180-00035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmer RL, Billings CJ, Diedesch-Rouse AC, Gallun FJ, & Lew HL (2011). Electrophysiological assessments of cognition and sensory processing in TBI: Applications for diagnosis, prognosis and rehabilitation. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 82(1), 4–15. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D, Cycowicz YM, & Gaeta H (2001). The novelty P3: an event-related brain potential (ERP) sign of the brain’s evaluation of novelty. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 25(4), 355–373. 10.1016/S0149-7634(01)00019-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P (2009). Neuronal gamma-band synchronization as a fundamental process in cortical computation. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 32, 209–24. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillan CM, & Daw ND (2016). Taking Psychiatry Research Online. Neuron, 91(1), 19–23. http://doi.org/10.1016Zj.neuron.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore CS, Marquardt CA, Kang SS, & Sponheim SR (2018). Reduced P3b brain response during sustained visual attention is associated with remote blast mTBI and current PTSD in U.S. military veterans. Behavioural Brain Research, 340, 174–182. 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes J, & Damborská A (2017). Event-Related Potentials as Biomarkers of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Activitas Nervosa Superior, 59(3–4), 87–90. 10.1007/s41470-017-0011-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grace J, amp Malloy PF (2001). Frontal systems behavior scale. Professional manual. [Google Scholar]

- Haneef Z, Levin HS, Frost JD, & Mizrahi EM (2013). Electroencephalography and Quantitative Electroencephalography in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 30(8), 653–656. 10.1089/neu.2012.2585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley DF, Chabot R, Mould WA, Morgan T, Naunheim R, Sheth KN, ... Prichep LS (2013). Use of Brain Electrical Activity for the Identification of Hematomas in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 30(24), 2051–2056. 10.1089/neu.2013.3062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley D, Prichep LS, Badjatia N, Bazarian J, Chiacchierini Ri. P., Curley KC, ... Huff JS (2017). A brain electrical activity (EEG) based biomarker of functional impairment in traumatic head injury: a multisite validation trial. Journal of Neurotrauma, 47, neu.2017.5004. 10.1089/neu.2017.5004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley D, Prichep LS, Bazarian J, Huff JS, Naunheim R, Garrett J, … Hack DC (2017). Emergency Department Triage of Traumatic Head Injury Using a Brain Electrical Activity Biomarker: A Multisite Prospective Observational Validation Trial. Academic Emergency Medicine, 24(5), 617–627. 10.1111/acem.13175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM, & McGue M (2003). Substance use disorders, externalizing psychopathology, and P300 event-related potential amplitude. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 48(2), 147–178. 10.1016/S0167-8760(03)00052-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, … Wang P (2010). Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry, 167(7), 748–751. http://doi.org/167/7/748 [pii] 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R (1986). A triarchic model of P300 amplitude. Psychophysiology. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00649.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NS, Crawford S, Wenden FJ, Moss NE, & Wade DT (1995). The Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire: a measure of symptoms commonly experienced after head injury and its reliability. Journal of Neurology, 242(9), 587–92. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8551320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo TK, & Li MY (2016). A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. 10.1016/jjcm.2016.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp B, Tabeling S, Moschner C, & Wessel K (2006). Fractionating the neural mechanisms of cognitive control. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 18(6), 949–965. 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.6.949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus N, Thompson EC, Krizman J, Cook K, White-Schwoch T, & LaBella CR (2016). Auditory biological marker of concussion in children. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 39009 10.1038/srep39009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson MJ, Fair JE, Farrer TJ, & Perlstein WM (2011). Predictors of performance monitoring abilities following traumatic brain injury: The influence of negative affect and cognitive sequelae. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 82(1), 61–68. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson MJ, Farrer TJ, & Clayson PE (2011). Cognitive control in mild traumatic brain injury: conflict monitoring and conflict adaptation. International Journal of Psychophysiology: Official Journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology, 82(1, 69–78. http://doi.Org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie ME, Johnston KM, Leclerc S, Lassonde M, & Dupuis F (2004). Visual P300 Effects Beyond Symptoms in Concussed College Athletes. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology (Neuropsychology, Development and Cognition: Section A), 26(1), 55–73. 10.1076/jcen.26.L55.23936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew HL, Poole JH, Castaneda A, Salerno RM, & Gray M (2006). Prognostic value of evoked and event-related potentials in moderate to severe brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 21(4), 350–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden DEJ (2005). The P300 : Where in the Brain Is It Produced and What Does It Tell Us ? The Neuroscientist: A Review Journal Bringing Neurobiology, Neurology and Psychiatry, 11(6), 563–576. 10.1177/1073858405280524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer AR, Hanlon FM, Claus ED, Dodd AB, Miller B, Mickey J, … Hutchison KE (2018). An Examination of Behavioral and Neuronal Effects of Comorbid Traumatic Brain Injury and Alcohol Use. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3(3), 294–302. http://doi.org/10.1016Zj.bpsc.2017.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer AR, Quinn DK, & Master CL (2017). The spectrum of mild traumatic brain injury: A review. Neurology, 89(6), 623–632. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrea M, Prichep L, Powell MR, Chabot R, & Barr WB (2010). Acute Effects and Recovery After Sport-Related Concussion. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 25(4), 283–292. 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181e67923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald BC, Flashman L. a, & Saykin AJ (2002). Executive dysfunction following traumatic brain injury: neural substrates and treatment strategies. NeuroRehabilitation, 17(4), 333–44. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12547981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon PJ, Hricik A, Yue JK, Puccio AM, Inoue T, Lingsma HF, … Vassar MJ (2014). Symptomatology and Functional Outcome in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Results from the Prospective TRACK-TBI Study. Journal of Neurotrauma, 31(1), 26–33. 10.1089/neu.2013.2984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Rosenthal R, & Rubin DB (1992). Comparing correlated correlation coefficients. Psychological Bulletin, 111(1), 172–175. 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, Dolan RJ, Friston KJ, & Dayan P (2012). Computational psychiatry. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(1), 72–80. 10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RD, Hillman CH, & Broglio SP (2014). The persistent influence of concussive injuries on cognitive control and neuroelectric function. Journal of Athletic Training, 49(1), 24–35. 10.4085/1062-6050-49.L01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott TF, McConnon ML, & Rieger BP (2012). Subacute to chronic mild traumatic brain injury. American Family Physician, 86(11), 1045–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naunheim RS, Treaster M, English J, Casner T, & Chabot R (2010). Use of brain electrical activity to quantify traumatic brain injury in the emergency department. Brain Injury, 24(11), 1324–1329. 10.3109/02699052.2010.506862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuis S, De Geus EJ, & Aston-Jones G (2011). The anatomical and functional relationship between the P3 and autonomic components of the orienting response. Psychophysiology, 48(2), 162–175. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01057.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan H, Whelan R, & Reilly RB (2010). FASTER: Fully Automated Statistical Thresholding for EEG artifact Rejection. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 192(1), 152–62. 10.1016/jjneumeth.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuwer MR, Hovda D. a, Schrader LM, & Vespa PM (2005). Routine and quantitative EEG in mild traumatic brain injury. Clinical Neurophysiology: Official Journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 116(9), 2001–25. 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell RG, Dockree PM, & Kelly SP (2012). A supramodal accumulation-to-bound signal that determines perceptual decisions in humans. Nature Neuroscience, 15(12), 1729–35. 10.1038/nn.3248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Marqui RD (2002). Standardized low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA): technical details. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol, 24 Suppl D, 5–12. http://doi.org/846 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich J (2007). Updating P300: an integrative theory of P3a and P3b. Clinical Neurophysiology: Official Journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 118(10), 2128–48. 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich J, & Kok A (1995). Cognitive and biological determinants of P300: an integrative review. Biol Psychol, 41(2), 103–146. http://doi.org/0301051195051309 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prichep LS, Ghosh Dastidar S, Jacquin A, Koppes W, Miller J, Radman T, ... Huff JS (2014). Classification algorithms for the identification of structural injury in TBI using brain electrical activity. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 53, 125–133. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2014.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prichep LS, McCrea M, Barr W, Powell M, & Chabot RJ (2013). Time Course of Clinical and Electrophysiological Recovery After Sport-Related Concussion. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 28(4), 266–273. 10.1097/HTR.0b013e318247b54e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prichep LS, Naunheim R, Bazarian J, Mould WA, & Hanley D (2015). Identification of Hematomas in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Using an Index of Quantitative Brain Electrical Activity. Journal of Neurotrauma, 32(1), 17–22. 10.1089/neu.2014.3365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DK, Mayer AR, Master CL, & Fann JR (2018). Prolonged postconcussive symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(2, 103–111. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17020235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp PE, Keyser DO, Albano A, Hernandez R, Gibson DB, Zambon RA, ... Nichols AS (2015). Traumatic Brain Injury Detection Using Electrophysiological Methods. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9(February), 1–32. 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohling ML, Larrabee GJ, Millis SR, Rohling ML, Larrabee GJ, & Millis SR (2012). The “ Miserable Minority ” Following Mild Traumatic Brain Injury : Who Are They and do Meta-Analyses Hide Them ?, 4046 10.1080/13854046.2011.647085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose SC, Fischer AN, & Heyer GL (2015). How long is too long? the lack of consensus regarding the post-concussion syndrome diagnosis. Brain Injury, 29(7–8), 798–803. 10.3109/02699052.2015.1004756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy M, Shohamy D, & Wager TD (2012). Ventromedial prefrontal-subcortical systems and the generation of affective meaning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 10.1016/j.tics.2012.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff R (2005). Two Decades of Advances in Understanding of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury, 20(1), 5–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seer C, Lange F, Georgiev D, Jahanshahi M, & Kopp B (2016). Event-Related Potentials and Cognition in Parkinson’s Disease: An Integrative Review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 691–714. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackman AJ, Salomons TV, Slagter H. a, Fox AS, Winter JJ, & Davidson RJ (2011). The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 12(3), 154–67. 10.1038/nrn2994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SA, Goldin Y, Conte MM, Goldfine AM, Mohamadpour M, Fidali BC, … Schiff ND (2017). Executive attention deficits after traumatic brain injury reflect impaired recruitment of resources. NeuroImage: Clinical, 14, 233–241. 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M, Donner TH, & Engel AK (2012). Spectral fingerprints of large-scale neuronal interactions. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 13(2), 121–34. 10.1038/nrn3137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis-Vivanco R, Rodriguez-Violante M, Rodriguez-Agudelo Y, Schilmann A, Rodriguez-Ortiz U, & Ricardo-Garcell J (2015). The P3a wave: A reliable neurophysiological measure of Parkinson’s disease duration and severity. Clinical Neurophysiology, 126(11), 2142–2149. 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltani M, & Knight RT (2000). Neural Origins of the P300. Critical Reviews in Neurobiology, 14(510), 199–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher RW, North DM, Curtin RT, Walker RA, Biver CJ, Gomez JF, & Salazar AM (2001). Traumatic Brain Injury, 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher RW, Walker RA, Gerson I, & Geisler FH (1989). EEG discriminant analyses of mild head trauma. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 73(2), 94–106. 10.1016/0013-4694(89)90188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twomey DM, Murphy PR, Kelly SP, & O’Connell RG (2015). The classic P300 encodes a build-to-threshold decision variable. European Journal of Neuroscience, (April), n/a-n/a. 10.1111/ejn.12936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Naalt J, Timmerman ME, de Koning ME, van der Horn HJ, Scheenen ME, Jacobs B, … Saykin AJ (2017). Symptomatology and Functional Outcome in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Results from the Prospective TRACK-TBI Study. Journal of Neurotrauma, 175(2), 798–803. 10.1089/neu.2015.3888 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Naalt J, Timmerman ME, de Koning ME, van der Horn HJ, Scheenen ME, Jacobs B, … Spikman JM (2017). Early predictors of outcome after mild traumatic brain injury (UPFRONT): an observational cohort study. The Lancet Neurology, 16(7), 532–540. 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30117-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller DA, Hazeltine E, & Wessel JR (2019). Common neural processes during action-stopping and infrequent stimulus detection : The frontocentral P3 as an index of generic motor inhibition. International Journal of Psychophysiology, (July 2018), 1–11. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MGH (2000). Electrophysiological indices of persistent post-concussion symptoms. Brain Injury, 14(9), 815–832. 10.1080/026990500421921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel JR (2018). Surprise: A More Realistic Framework for Studying Action Stopping? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(9), 741–744. 10.1016/j.tics.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienke AS, Basar-Eroglu C, Schmiedt-Fehr C, & Mathes B (2018). Novelty N2-P3a complex and theta oscillations reflect improving neural coordination within frontal brain networks during adolescence. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12(September), 1–14. 10.1111/j.1467-9817.2009.01401.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MJ, Harkrider AW, & King KA (2014). The effects of visual distracter complexity on auditory evoked p3b in contact sports athletes. Developmental Neuropsychology, 39(2), 113–130. 10.1080/87565641.2013.870177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt ST, Lovejoy DW, Pearlson GD, & Stevens MC (2010). Decreased prefrontal cortex activity in mild traumatic brain injury during performance of an auditory oddball task. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 4(3–4), 232–247. 10.1007/s11682-010-9102-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and code for this experiment are available on the PRED+CT website: www.predictsite.com; Accession #d009.