Abstract

Receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) regulates cell fate and pro-inflammatory signaling downstream of multiple innate immune pathways, including those initiated by TNF-α, Toll-like Receptor (TLR) ligands, and Interferons (IFNs). Genetic ablation of Ripk1 results in perinatal lethality arising from both RIPK3-mediated necroptosis and FADD/caspase-8-driven apoptosis. IFNs are thought to contribute to the lethality of Ripk1-deficient mice by activating inopportune cell death during parturition, but how IFNs activate cell death in the absence of RIPK1 is not understood. Here, we show that Z-form nucleic acid binding protein 1 (ZBP1, also known as DAI) drives IFN-stimulated cell death in settings of RIPK1 deficiency. IFN-activated Jak/STAT signaling induces robust expression of ZBP1, which complexes with RIPK3 in the absence of RIPK1 to trigger RIPK3-driven pathways of caspase-8-mediated apoptosis and MLKL-driven necroptosis. In vivo, deletion of either Zbp1 or core IFN signaling components prolong viability of Ripk1−/− mice for up to three months beyond parturition. Together, these studies implicate ZBP1 as the dominant activator of IFN-driven RIPK3 activation and perinatal lethality in the absence of RIPK1.

Keywords: Interferons, RIPK1, RIPK3, FADD, caspase-8, MLKL, necrosis, necroptosis, apoptosis

Introduction

RIPK1 was discovered as a serine/threonine kinase that interacted with the cytoplasmic tails of death receptors Fas/CD95 and TNFR1 (1). Subsequently, RIPK1 was also found to regulate NF-κB and mediate cell survival responses downstream of TNFR1 (2). In support of a survival function for RIPK1 in vivo, germline ablation of the Ripk1 gene resulted in abrupt perinatal lethality; mice homozygously null for Ripk1 were born at expected Mendelian frequencies, but died within 48 hours of birth (3).

The perinatal lethality of Ripk1-deficient mice remained largely unexplained for fifteen years, until three studies demonstrated that this lethal phenotype could be rescued by the concurrent ablation of both FADD/caspase-8-mediated apoptosis and RIPK3-driven necroptosis pathways (4–6). Mice triply-deficient in Ripk1, Ripk3 and either Fadd or Caspase-8 exhibit no overt developmental defects, matured into adulthood, are fertile, and mount robust immune responses to virus challenge (4–6). Of note, whereas activation of necroptosis in Ripk1−/− mice is solely reliant on RIPK3, activation of FADD/caspase-8 mediated apoptosis in these mice can be either RIPK3-dependent or –independent (4). The RIPK3-independent apoptotic signal is predominantly mediated by TNF-α (4, 6). However, the signal(s) responsible for activating RIPK3-mediated cell death (both necroptosis and apoptosis) in these mice are unclear. In cells, multiple innate-immune signaling pathways, including those initiated by TLR3/TRIF- and type I/II IFN signaling, have been shown to activate RIPK3 in settings of Ripk1-deficiency (4, 5). As these pathways are stimulated during innate-immune responses to viruses and microbes, a current model explaining the postnatal lethality of Ripk1-deficient mice suggests that RIPK1 restrains RIPK3-independent apoptotic death signaling by TNF-α, as well as RIPK3-dependent death signaling by numerous stimuli, including type I/II IFNs, upon exposure to viruses and microbes during and after the process of mammalian parturition. It is, however, currently unclear how IFNs activate RIPK3 to drive apoptosis and necroptosis in Ripk1−/− cells, and the contribution of IFN-mediated cell death to the perinatal lethality of Ripk1−/− mice.

Here, we show that the ISG product ZBP1 is responsible for IFN-induced activation of RIPK3 and consequent apoptotic and necroptotic cell death in Ripk1−/− cells. In wild-type cells, a basal RIPK1-RIPK3 complex prevents ZBP1 from associating with RIPK3, restrains RIPK3 activity, and protects cells from IFN-induced death. However, when RIPK1 expression is compromised, exposure to IFNs results in the formation of a ZBP1-RIPK3 complex that activates parallel pathways of apoptosis and necroptosis. Apoptosis is mediated by caspase-8 and proceeds independently of the kinase activity of RIPK3, while necroptosis is reliant on MLKL and RIPK3 activity. In vivo, the combined elimination of ZBP1 and caspase-8 extended the lifespan of Ripk1−/− mice by over one month. Furthermore, we show that elimination of components required for IFN signaling (e.g., STAT1, IFNGR1, IFNAR1, IFNGR1+IFNAR1) phenocopy to various degrees the rescue conferred by ablation of ZBP1. Together, these results implicate ZBP1 as the dominant instigator of IFN-driven cell death during RIPK1 deficiency, and identify the IFN-ZBP1 axis as an essential contributor to RIPK3 activation and perinatal lethality in Ripk1−/− mice.

Materials and Methods

Cells and reagents

Early passage Ripk1−/− (3), Ripk1−/− Ripk3−/− (4, 5), Zbp1−/− (7) and Ripk1−/− Zbp1−/− MEFs were generated in-house from E14.5 embryos and used within five passages in all experiments. Cell viability was determined by Trypan blue exclusion or on an Incucyte Kinetic Live Cell Imaging System. Cytokines and chemicals were from the following sources: mIFN-β (PBL), mIFN-γ (R&D Systems), mTNF-α (R&D Systems), mTRAIL (R&D Systems), mGITRL (Sigma), z-VAD-fmk (Calbiochem), z-IETD.fmk (R&D Systems), cycloheximide (Sigma), actinomycin D (MD Biochemical), RIPK3 inhibitor GSK’843 (GlaskoSmithKline) (8), JAK Inhibitor I (Calbiochem). Antibodies for immunoblot analyses were obtained from Millipore (anti-MLKL, anti-JAK1), BD Biosciences (anti-STAT1 and anti-RIPK1), ProSci (anti-RIPK3 and anti-c-FLIP), Genentech (anti-pRIPK3), Santa Cruz Biotechnology (anti-MnSOD, anti-PKR), Cell Signaling (anti-caspase-8, anti-cleaved caspase-8, anti-TRAF2, and anti-p-STAT1), Abcam (anti-p-MLKL), AdipoGen (anti-ZBP1), and Sigma (anti-β-actin). The anti-p-MLKL used for immunofluorescence (IF) studies has been described before (9). The anti-cleaved caspase-8 for IF was obtained from Cell Signaling. HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Secondary antibodies for IF were procured from Thermo Fisher Scientific. All other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise noted. All cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10–15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics.

Mice

Zbp1−/− (7), Ripk1−/− (3), Ripk3−/− (10), Casp8−/− (11), Tnfr1−/− (12), Ifnar1−/− (13), Ifngr1−/− (14), Stat1−/− (15), Sting−/− (16), and Mavs−/− (17) mice have been previously described. Crosses were produced and genotyped by tail clip PCR, as described earlier (5). WT (C57BL/6J) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Mice were bred and maintained at the Fox Chase Cancer Center, UTHSCSA and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in accordance with protocols approved by the respective Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of these institutions.

RNAi

For acute RNAi, wild-type MEFs (5 X 105 per condition) were seeded into six-well plates and transfected with pools of four proprietary siRNAs (SMARTpool; Dharmacon) to the specific target mRNA at 25nM using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) as a transfection reagent. Non-targeting (scrambled) siRNAs (Dharmacon) were used as controls. Cells were used 72 hours postinfection for experiments. For stable RNAi, prepackaged shRNA-expressing lentiviral particles (Sigma) were used. At least four distinct shRNAs per target were tested for knockdown efficiency by immunoblot analysis. The most efficient shRNAs were used to generate at least two individual stable populations of MEFs for experimental use.

Co-immunoprecipitation

MEFs (5 X 105 per condition) were harvested in lysis buffer [1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 150mM NaCl, 20mM Hepes (pH 7.3), 5mM EDTA, 5mM NaF, 0.2mM NaVO3(ortho), and complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche)]. After clarification of lysates by centrifugation, 2μg of antibody was added to each sample followed by rotating incubation at 4°C overnight. Samples were then supplemented with protein A/G agarose slurry (40μL) and incubated for 2 hours, washed 4x in ice-cold lysis buffer, and bound proteins were eluded by boiling in SDS sample buffer. Eluted proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting, as described previously (18).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

MEFs were plated on 8-well glass slides (EMD Millipore), and allowed to adhere for at least 24 hr before use in experiments. Following IFN treatment, cells were fixed with freshly-prepared 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100, blocked with MAXblock™ Blocking Medium (Active Motif), and incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C. After three washes in PBS, slides were incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hr at room temperature. Following an additional three washes in PBS, slides were mounted in ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen) and imaged by confocal microscopy on a Leica SP8 instrument. Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: anti-phospho mMLKL (1:7000), anti-cleaved caspase-8 (1:500).

Statistics

Statistical significance was determined by use of Student’s t-test. P-values of 0.05 or lower were considered significant. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software.

Results

IFN-γ activates RIPK3-driven parallel pathways of necroptosis and apoptosis in Ripk1−/− MEFs

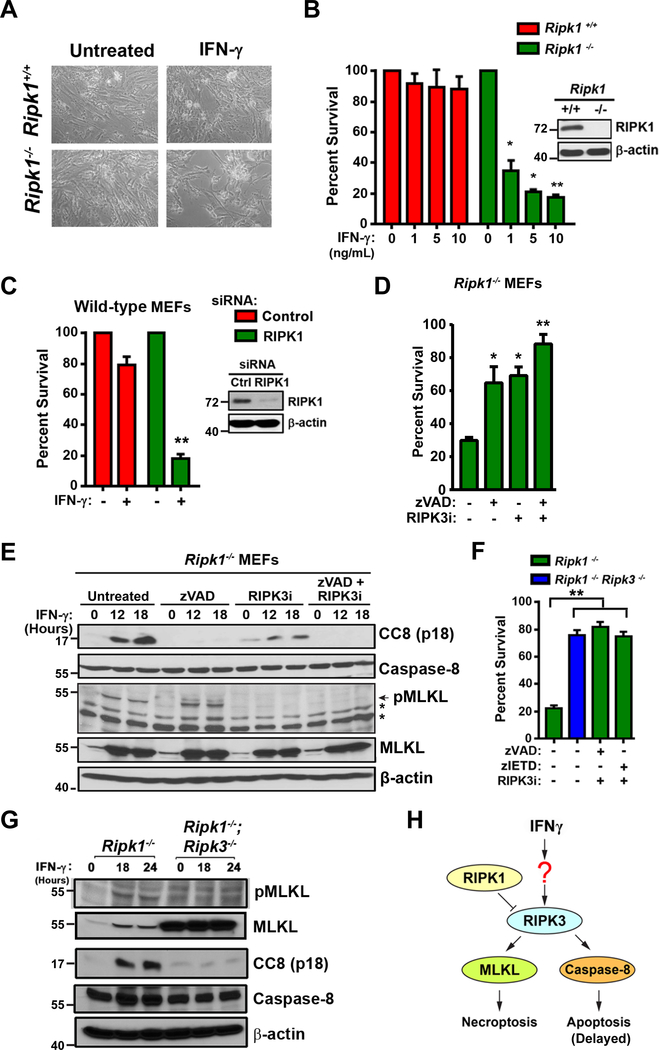

We and others have previously demonstrated that IFN-γ is toxic to primary murine embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) lacking RIPK1, but the mechanism by which IFN-γ activated cell death was unclear (4, 5, 19). To examine this phenomenon further, early-passage Ripk1−/− MEFs and wild-type littermate-control MEFs were treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml). Cell death was monitored over a time course of 48 h, by which time Ripk1−/− MEFs were mostly dead, while wild-type MEFs were largely unaffected (Fig. 1A). IFN-γ triggered cell death at doses as low as 1 ng/ml (Fig. 1B). Similar results were observed with type I IFNs (IFN-α/β, Fig. S1A). Acute siRNA-mediated knock-down of RIPK1 expression in wild-type MEFs sensitized these cells to IFN-γ-induced cell death at levels comparable to those seen in Ripk1−/− MEFs (Fig. 1C). Combined inhibition of caspase activity and RIPK3 kinase function protected Ripk1−/− MEFs from IFN-γ (Fig. 1D), as well as from type I IFNs (Fig. S1B), whereas neither caspase inhibition nor RIPK3 kinase blockade were singly capable of fully rescuing Ripk1−/− MEFs from IFN-γ-induced cell death. In agreement with these observations, IFN-γ was found to activate both caspase-8 and MLKL in Ripk1−/− MEFs (Fig. 1E). Interestingly, a kinetic analysis of caspase-8 and MLKL activation in IFN-exposed Ripk1−/− MEFs showed that MLKL was activated more rapidly, and to a greater extent, than caspase-8 (Fig. S1 C,D). The pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD on its own efficiently prevented caspase-8 activation and a RIPK3 kinase inhibitor blocked MLKL phosphorylation; expectedly, the combination of these agents prevented activation of both caspase-8 and MLKL (Fig. 1E). Notably, Fadd−/− MEFs are also very susceptible to IFN-induced cell death, but in these cells, zVAD had no protective effect, while RIPK3 kinase blockade was singly capable of fully protecting against IFN-γ (Fig. S2A). In agreement, IFN-γ treatment of Fadd−/− MEFs induced phosphorylation of MLKL but did not detectably activate caspase-8 (Fig. S2B). Thus, IFNs activate both necroptosis and apoptosis in Ripk1−/− MEFs, but only necroptosis in Fadd−/− MEFs. It is noteworthy that Fadd−/− MEFs were also protected from IFN-induced cell death by the RIPK1 inhibitor necrostatin-1 (Fig. S2A), suggesting that IFNs activate necroptosis by different mechanisms depending on the presence or absence of RIPK1 (see Discussion).

Figure 1. IFNs activate RIPK3 dependent apoptosis and necroptosis in the absence of RIPK1.

(A) Photomicrographs of Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1−/− murine embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) treated with recombinant murine IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) for 36 hours. (B) Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1−/− MEFs were treated with the indicated doses of mIFN-γ and cell viability was determined at 36 hours. RIPK1 protein expression was confirmed by immunoblotting (inset). (C) Ripk1+/+ MEFs were transfected with nonspecific or RIPK1-specific siRNAs. After 48 hours of transfection, cells were treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) and cell viability was determined 36 hours post-treatment. Knockdown of RIPK1 expression was confirmed by immunoblotting (inset). (D) Ripk1−/− MEFs were treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD (25 μM) or/and 5μM of RIPK3 kinase inhibitor (GSK’843). Cell viability was determined 36 hours post-treatment. (E) Ripk1−/− MEFs treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) in the presence of zVAD (50 μM), GSK’843 (5 μM), or both inhibitors together were examined for cleaved caspase-8 p18 subunit (CC8) or phosphorylated MLKL (pMLKL) by immunoblot analysis at the indicated times. (F) Ripk1−/− and Ripk1−/− Ripk3−/− double knock-out MEFs were treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) and cell viability was determined after 36 hours. In parallel, Ripk1−/− MEFs were treated with IFN-γ in the presence of pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD (50 μM) or the caspase-8 inhibitor zIETD (50 μM) and 5μM of RIPK3 kinase inhibitor (GSK’843). (G) Whole cell lysates extracted from IFN-γ treated Ripk1−/− and Ripk1−/−Ripk3−/− double knock-out MEFs were examined for pMLKL or CC8 (p18 subunit) by immunoblot analysis at the indicated times. (H) Schematic of IFN-induced cell death via RIPK3-dependent activation of both caspase-8 mediated apoptosis and MLKL-driven necroptosis in cells lacking RIPK1. In panels showing quantification of cell survival data, viability of cells in untreated cultures was arbitrarily set to 100%. Molecular masses (in kDa) are shown to the left of immunoblots. Error bars represent mean +/− S.D. of technical replicates from a single experiment. In panels B and C, statistical significance was determined by comparing IFN-γ treated groups to untreated controls. In panels D and F, these comparisons were made between inhibitor-treated groups to their untreated (but IFN-γ exposed) controls. Viability and immunoblot experiments shown in this figure were performed at least three times each, with similar results. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.005.

While it is known that IFN-induced necroptosis requires RIPK3 and MLKL (4, 5, 19), it remains unclear whether apoptosis induction also relies on RIPK3. In other scenarios, for example upon IAV infection, RIPK3 can simultaneously activate both apoptosis and necroptosis (20). To test if RIPK3 was upstream of both cell death modalities in Ripk1−/− MEFs exposed to IFN-γ, we treated primary MEFs doubly-deficient in RIPK1 and RIPK3 with IFN-γ and evaluated their capacity to undergo cell death over a 36 h timeframe. Ripk1−/− Ripk3−/− double-knockout MEFs were almost completely (~80%) protected from IFN-γ-induced cell death; their viability was comparable to Ripk1−/− single knockouts treated with a RIPK3 kinase inhibitor and either pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD or the caspase-8 inhibitor zIETD (Fig. 1F). Co-ablating RIPK3 effectively nullified both IFN-γ-induced phosphorylation of MLKL and cleavage of caspase-8 (Fig. 1G, Fig. S1C,D). Of note, diminished basal levels of MLKL are detected in the Ripk1−/− MEFs, as was previously observed in Fadd−/− MEFs (21), and likely represent a compensatory response to unrestrained RIPK3 activity in these cells. In agreement with this possibility, co-deleting RIPK3 in Ripk1−/− MEFs restored MLKL expression (Fig. 1G, Fig. S1E). Together, these results demonstrate that IFNs activate RIPK3 and drive both apoptosis and necroptosis in the absence of RIPK1. Apoptosis induced by IFNs requires caspase-8 and RIPK3 scaffold function, while necroptosis is mediated by MLKL and relies on RIPK3 kinase activity (Fig. 1H).

Induction of cell death by IFN-γ in Ripk1−/− MEFs requires active Jak/STAT-mediated transcription and translation

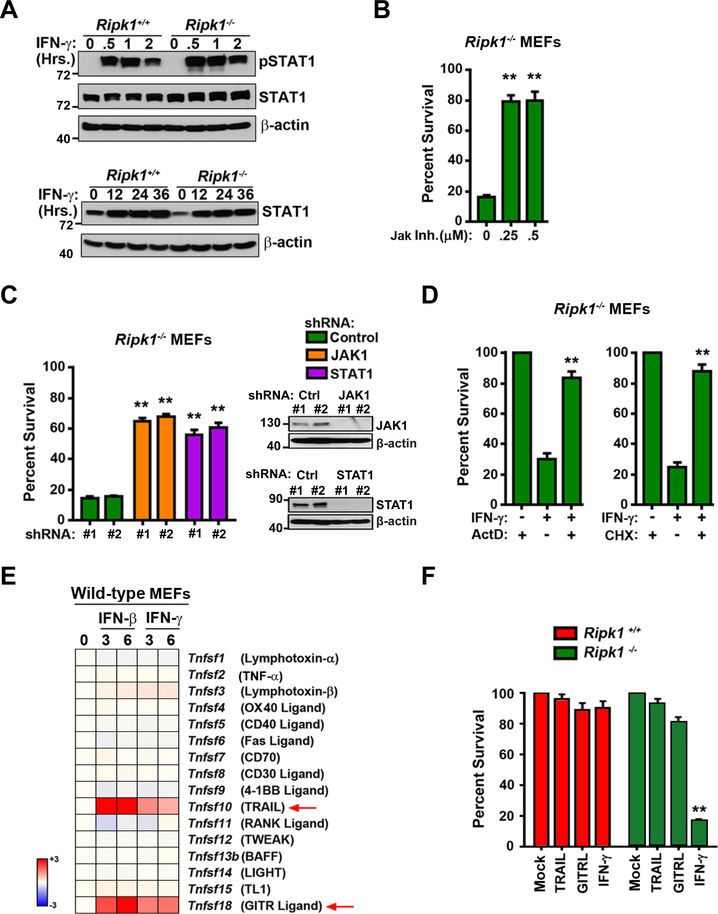

IFN-γ typically mediates its cellular effects by activating a Jak/STAT-driven transcriptional program that induces the expression of hundreds of genes, called ISGs. After verifying that activation of Jak-STAT signaling, as measured by immunoblotting for pSTAT1, was unaltered in Ripk1−/− MEFs (Fig. 2A), we tested if this signaling axis was necessary for IFN-γ-driven cell death responses in these cells. Pharmacological inhibition of Jak kinase activity (Fig. 2B, S1B) or RNAi-mediated ablation of Jak1 or STAT1 expression efficiently protected Ripk1−/− cells from IFN-triggered death (Fig. 2C). In agreement with a role for ongoing transcription and translation in IFN-induced cell death, pretreatment with the RNA Polymerase II inhibitor actinomycin D or the translation elongation inhibitor cycloheximide also rescued Ripk1−/− MEFs from IFN-induced death (Fig. 2D, S1B). These results strongly indicate that IFNs, in contrast to TNF, do not activate RIPK3 directly, but rather do so by inducing the expression of gene(s) that are then capable of triggering RIPK3 in Ripk1−/− cells. These findings are consistent with our previous observations in the setting of FADD deficiency, where IFN-induced Jak/STAT-mediated transcription and consequent activation of PKR served to initiate RIPK1/3-dependent necroptosis (19).

Figure 2. IFN-induced cell death requires Jak/STAT-mediated transcription and translation.

(A) Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1−/− MEFs were treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) for 0.5,1 or 2 hours and were examined for pSTAT1 and STAT1 by immunoblot analysis. β-actin was used as a loading control. In parallel, Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1−/− MEFs were treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) for 12, 24 or 36 hours and were examined for STAT1 induction by immunoblot analysis. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) Ripk1−/− MEFs were pre-treated with increasing concentrations (250 nM, 500 nM) of JAK inhibitor I for 1 hour prior to IFN-γ treatment (10 ng/ml) and cell viability was determined at 36 hours. (C) Ripk1−/− MEFs were transfected with non-targeting shRNAs (control), or with JAK1 or STAT1-specific shRNAs. Two distinct shRNAs (#1 and #2) were used in each case. After 48 hours of transfection, cells were treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) and cell viability was determined 36 hours post-treatment. Knockdown of JAK1 and STAT1 expression was confirmed by immunoblotting (inset). (D) Ripk1−/− MEFs were treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) in the presence of actinomycin D (ActD 25 ng/ml) or cycloheximide (CHX 250 ng/ml) and cell viability was determined 36 hours post treatment. (E) TNF superfamily genes induced at least twofold by IFN-γ or IFN-β within 6 hours of treatment in Ripk1−/− MEFs were determined by DNA microarray analysis as described earlier (37). Heat bar = log2 scale. Signal in untreated MEFs was normalized to 1 (white). (F) Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1−/− MEFs were treated with mTRAIL (1 μg/ml), mGITRL (1 μg/ml) or mIFN-γ (10 ng/ml) and cell viability was determined after 36 hours. In panels showing quantification of cell survival data, viability of cells in untreated cultures was arbitrarily set to 100%. Molecular masses (in kDa) are shown to the left of immunoblots. Error bars represent mean +/− S.D. of technical replicates from one experiment. In panels B and D, statistical significance was determined by comparing inhibitor-treated groups to their untreated (but IFN-γ exposed) controls. In panel F, statistical significance was determined by comparing cytokine-treated groups to untreated controls. Viability and immunoblot experiments shown in this figure were performed at least three times each, with similar results. ** p < 0.005.

As IFNs induce expression of select members of the TNF superfamily (TNFSF) of cytokines, and as some TNFSFs (including TNF-α and TRAIL) are known activators of RIPK3 (22), we next asked if IFNs-induced RIPK3 activation was mediated by specific TNFSFs. To test this possibility, we first carried out DNA microarray analyses to identify which TNFSF cytokines were inducible by IFNs in MEFs. From this analysis, we determined that only TRAIL (encoded by Tnfsf10) and GITR Ligand (Tnfsf18) were induced to any significant extent by either IFN-γ or IFN-β (Fig. 2E). Exposure of Ripk1−/− MEFs to recombinant TRAIL or GITR Ligand, however, did not induce any appreciable cell death in these cells even at a dose (1μg/ml) that was 100-fold higher than a potently cytotoxic dose (10 ng/ml) of IFN-γ (Fig. 2F). IFN-triggered cell death in Ripk1−/− MEFs is thus unlikely to be mediated by an IFN-inducible member of the TNF superfamily.

The transcription factor NF-κB is activated by IFNs and can protect against IFN-induced necroptosis by inducing a transcriptional cell-survival program (19). As NF-κB activation by TNF-α requires RIPK1, we next tested if IFNs also activated NF-κB via RIPK1, and if this requirement for RIPK1 in IFN signaling might explain the susceptibility of Ripk1−/− MEFs to IFNs. We found that, unlike the case with TNF-α, NF-κB activation (Fig. S3A) and induction of the NF-κB target gene product MnSOD (Fig. S3B) by IFN-γ was largely intact in Ripk1−/− MEFs. Moreover TRAF2 and c-FLIP levels, shown previously to function as determinants of susceptibility to TNF-α in Ripk1−/− MEFs (4, 6), were also unaltered by IFN-γ treatment (Fig. S3C). These results suggest that the sensitivity of Ripk1−/− MEFs to IFNs does not arise from defects in NF-κB signaling.

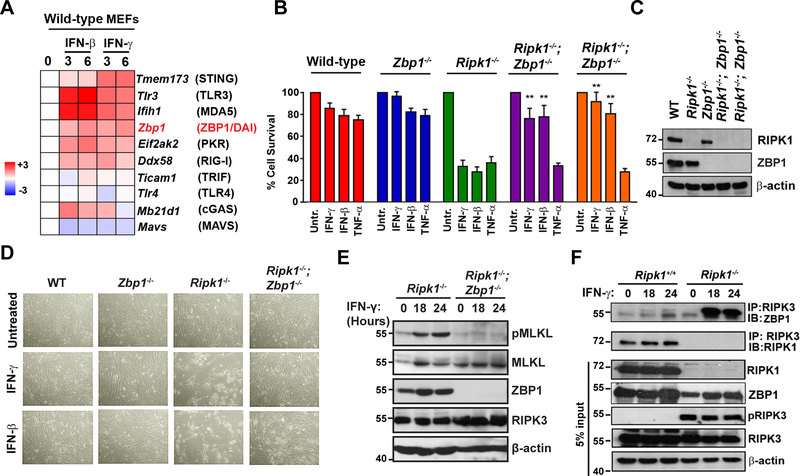

ZBP1 activates RIPK3 after IFN stimulation of Ripk1−/− MEFs

Having implicated JAK/STAT-driven transcription of ISGs as necessary for death of Ripk1−/− MEFs, and having ruled out ISG-encoded TNF superfamily members or diminished NF-κB transcriptional activity as possible drivers of IFN-induced cell death in these cells, we then examined if IFN-regulated innate-immune sensor pathways known to stimulate RIPK3 were responsible for activating this kinase upon exposure to IFNs. Multiple innate pathways have been shown to trigger necroptosis, including those initiated by TLR3/4, cGAS, RLRs, ZBP1, and PKR (19, 22, 23), and signaling nodes in each of these pathways are ISGs (Fig. 3A). We therefore screened each of these pathways by CRISPR and genetic approaches to test if they accounted for RIPK3 activation in Ripk1−/− MEFs. We found that elimination of PKR (encoded by eif2ak2) was able to only modestly protect Ripk1−/− MEFs from IFNs (Fig. S4A), in contrast to our previous results implicating this kinase in IFN-activated necroptosis in Fadd−/− MEFs (19) (see Discussion). However, we discovered that deletion of the gene Zbp1 was able to almost completely prevent IFN-induced cell death Ripk1−/− MEFs (Figs. 3B, D). Ripk1−/−Zbp1−/− double-knockout MEFs from two separate crosses remained ~80% viable 48 h after exposure to IFN-γ or IFN-β, while <40% Ripk1−/− MEFs were alive at this time (Figs. 3B, D). Ripk1−/−Zbp1−/− double-knockout MEFs remained as susceptible to TNF-α-mediated apoptotic death as Ripk1−/− MEFs, demonstrating that in the absence of RIPK1, ZBP1 is uniquely required to activate cell death upon stimulation by IFNs but not TNF-α (Fig. 3B). RIPK1 and protein levels in each of the MEF populations used in this study are shown in Fig. 3C. While IFN-γ induced MLKL phosphorylation in Ripk1−/− cells, Ripk1−/−Zbp1−/− double-knockout MEFs had almost-undetectable levels of pMLKL following IFN treatment (Fig. 3E). The deletion of Zbp1 did not significantly impact levels of either MLKL or RIPK3 (Fig. 3E). In Ripk1−/− cells, IFN-γ robustly promoted association of ZBP1 with RIPK3, while an association was not seen in Ripk1+/+ cells (Fig. 3F), although Zbp1 was induced by IFN to the same extent in both Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1−/− cells (Fig. S4B). Instead, in cells containing RIPK1, a basal RIPK1-RIPK3 complex was observed that did not alter in abundance with IFN treatment (Fig. 3F). Phosphorylated RIPK3 was only seen in Ripk1−/− cells, but not in cells containing RIPK1 (Fig. 3F). As the phospho-RIPK3 signal in Ripk1−/− MEFs was basally present and unaltered by exposure to IFN, it likely represents a form of autophosphorylated RIPK3 that is normally restrained by constitutive association with RIPK1 (24). Together, these results demonstrate that ZBP1 mediates cell death in IFN-exposed cells lacking RIPK1, and that RIPK1 normally functions to inhibit such death by complexing with RIPK3, preventing its autophosphorylation, and blocking its association with ZBP1.

Figure 3. ZBP1 mediates IFN-induced RIPK3 activation and cell death in Ripk1−/− MEFs.

(A) Heatmap showing IFN inducibility of necroptosis-activating innate pathway genes. MEFs were treated with IFN-β or IFN-γ for 3 or 6 hours, and the indicated genes ranked by fold induction following treatment in Ripk1+/+ MEFs. Heat bar = log2 scale. Signal in untreated MEFs was normalized to 1 (white). (B) Wild-type, Ripk1−/−, Zbp1−/−, and Ripk1−/−Zbp1−/− MEFs from two different embryos were treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml), IFN-β (10 ng/ml) or TNF-α (10 ng/ml) and cell viability was determined 36 hours post-treatment. (C) Wild-type, Ripk1−/−, Zbp1−/−, and Ripk1−/−Zbp1−/− MEFs from two different embryos were treated with IFN-γ (50 ng/ml) for 24 hours and were examined for RIPK1 by immunoblot analysis. (D) Photomicrographs of WT, Ripk1−/−, Zbp1−/−, and Ripk1−/−Zbp1−/− MEFs treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) or IFN-β (10 ng/ml) for 36 hours. (E) Ripk1−/− and Ripk1−/−Zbp1−/− MEFs were treated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) for 18 or 24 hours and were examined for pMLKL by immunoblot analysis. (F) Anti-RIPK3 immunoprecipitates from IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) treated Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1−/− MEFs were examined for the presence of ZBP1. Whole-cell extract (5% input) was examined in parallel for RIPK1 and RIPK3 proteins. Immunoblotting for β-actin was used as a loading control (C, E, F). In panels showing quantification of cell survival data, viability of cells in untreated cultures was arbitrarily set to 100%. Molecular masses (in kDa) are shown to the left of immunoblots. Error bars represent mean +/− S.D. of technical replicates from one experiment. In panel B, statistical significance was determined by comparing cytokine-treated groups to untreated controls. Viability and immunoblot experiments shown in this figure were performed at least three times each, with similar results. ** p < 0.005

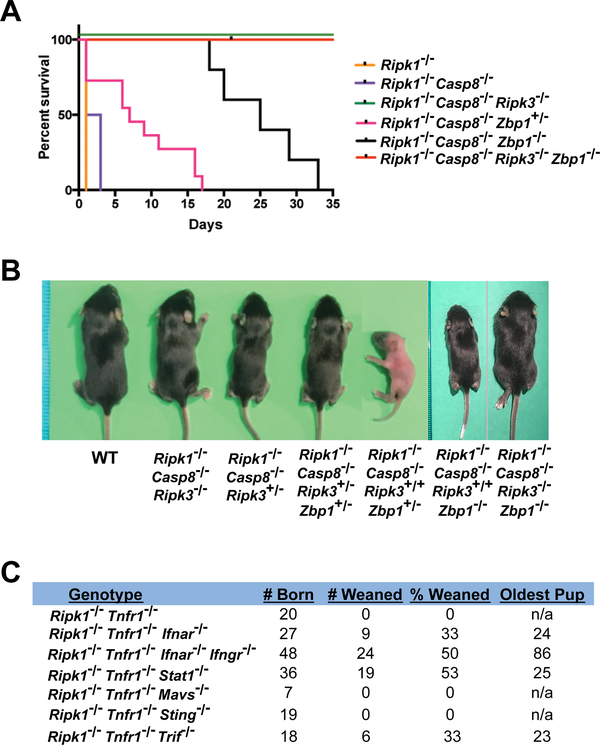

Zbp1 deletion partially rescues RIPK3-dependent perinatal lethality of Ripk1−/− mice

Ripk1−/− mice fail to survive beyond birth due to the aberrant activation of both caspase-8 mediated apoptosis and RIPK3-mediated necroptosis (4–6). Ripk1−/−Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− mice are weaned at the expected frequencies and develop normally, but eventually manifest an acute lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) due to defects in Fas-induced apoptosis of T cells (4–6). TNF-α mediates aberrant RIPK3-independent caspase-8 activation in Ripk1−/− mice, as evidenced by the ability of Ripk1−/−Tnfr1−/−Ripk3−/− triple-knockout mice, but neither Ripk1−/−Tnfr1−/− nor Ripk1−/−Ripk3−/− double-knockout mice to survive to adulthood (4, 6). However, the signals that drive RIPK3-dependent necroptosis (and apoptosis) in settings of RIPK1 deficiency are currently unclear. Given that IFNs activate RIPK3-driven cell death in Ripk1−/− cells (Fig. 1) and that ZBP1 mediates this cell death (Fig. 3), we next determined the contribution of ZBP1 to the RIPK3-dependent lethality of Ripk1−/− mice. To this end, we examined the effect of Zbp1 loss on the survival of Ripk1−/− mice, in which the TNF-α-mediated RIPK3-independent apoptosis signal was neutralized (via co-deletion of Caspase-8). We found that Ripk1−/−Casp8−/−Zbp1−/− mice were born at the expected Mendelian frequency and survived for up to five weeks (Fig. 4A). Thus, similar to RIPK3-deficiency, the absence of Zbp1 suppresses the lethality of Ripk1−/−Casp8−/− mice at parturition; however, in contrast to Ripk1−/−Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− mice which develop into fertile adults, Ripk1−/−Casp8−/−Zbp1−/− mice become severely runted within the first three weeks and ultimately fail to thrive. Notably, a single allele of Zbp1 is tolerated in Ripk1−/−Casp8−/− mice and extends the lifespan by up to two weeks (Fig. 4B), highlighting the survival benefit of reducing ZBP1 levels below a lethal threshold. Together, these data demonstrate that ZBP1 is a dominant, but not sole, instigator of inopportune RIPK3 activity in Ripk1−/− mice.

Figure 4. ZBP1 and IFN signaling contribute to perinatal lethality of RIPK1-deficient mice.

(A) Kaplan-Meier survival plots of comparing the survival of the indicated Ripk1−/−-Casp8−/− mice lacking one or both alleles of Zbp1. (B) Representative images of the indicated mice at 13 days post parturition. (P13). (C) Survival table for the indicated compound mutant mice showing number of pups weaned and age of oldest mouse at death.

Eliminating IFN signaling delays RIPK3-dependent lethality of Ripk1−/− mice

As ZBP1 is an ISG, and as both type I and type II IFNs drive RIPK3 activation via ZBP1 in Ripk1−/− cells, we next evaluated the contribution of IFNs to aberrant RIPK3 activation in, and consequent perinatal lethality of, Ripk1−/− mice. In these studies, aberrant TNF-induced RIPK3-independent caspase-8 activity was nullified by deletion of Tnfr1, which in this context is functionally equivalent to deleting caspase-8 (4, 6). Elimination of type I IFN signaling (Ripk1−/−Tnfr1−/−Ifnar1−/−) prolonged lifespan or Ripk1−/− mice by up to a month, and abolishing both type I and type II IFN signaling (Ripk1−/−Tnfr1−/−Ifnar1−/−Ifngr1−/−) extended the viability of Ripk1−/− mice for up to almost three months (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, eliminating the key downstream IFN signal transducer STAT1 in this setting did not extend viability beyond one month, indicating that alternate STAT1-independent IFN signals may operate to drive RIPK3 activation in Ripk1−/−Tnfr1−/−Stat1−/− animals during adolescence (Fig. 4C).

Three pathogen-sensing pathways, those initiated by TLR3/4, RLRs, and cGAS, are considered the primary triggers of type I IFN production in response to viral and microbial infections, as well as to endogenous ligands during sterile inflammation, in most cell types (25). To examine if any of these pathways were responsible for lethal IFN production during parturition of Ripk1−/− mice, we eliminated genes encoding key nodes in each of these pathways (Trif for TLR3/4 signaling, Mavs for RLRs and Sting for cGAS) in Ripk1−/−Tnfr1−/− mice, and monitored progeny for viability. Singly eliminating either Mavs or Sting did not provide any survival benefit to Ripk1−/−Tnfr1−/− mice, indicating that RLRs and cGAS are each redundant for RIPK3 activation and consequent lethality in Ripk1−/−Tnfr1−/− mice. Interestingly, deleting Trif extended the lifespan of Ripk1−/−Tnfr1−/− mice by about one month, phenocopying deletion of Ifnar1 in these animals (Fig. 4C). Although these results are suggestive of an important role for TLR3/4 signaling in production of lethal IFN in Ripk1−/−Tnfr1−/− mice, an alternative, and indeed more likely, explanation for the protective effects conferred by deleting Trif is that TRIF can directly activate RIPK3, independently of its role in IFN production (26, 27). Altogether, these data implicate IFNs as key instigators of lethal RIPK3 activation in Ripk1−/− mice.

Discussion

We have previously shown that IFNs can activate RIPK3-dependent cell death in the absence of RIPK1 (4, 5), but the molecular mechanisms by which IFN signaling stimulates RIPK3 activity have remained unclear. In this study, we identify ZBP1 as the dominant upstream activator of IFN-induced RIPK3-dependent cell death in settings of RIPK1 deficiency. IFNs, via canonical Jak/STAT signaling, induce the expression of ZBP1, which, if RIPK1 is absent, associates with RIPK3 and triggers cell death signaling. Under steady-state conditions in wild-type MEFs, a basal association between RIPK1 and RIPK3 restrains RIPK3 to prevent association with ZBP1. Even when ZBP1 levels are boosted by IFN stimulation, RIPK1 can prevent formation of the ZBP1-RIPK3 complex and wild type MEFs survive IFN exposure. When RIPK1 is absent, or when its RHIM is deleted (24, 28), RIPK3 is no longer restricted and is licensed to associate with ZBP1 (this study). Under these conditions, elevation of ZBP1 mRNA and protein levels following exposure to IFNs results in formation of a ZBP1-RIPK3 complex that induces both necroptosis, mediated by MLKL and delayed apoptosis, via caspase-8. It will interesting to test if IRF-1, shown previously to mediate Zbp1 induction during virus infections (29), and to synergize with STAT1 in the induction of a subset of ISGs (30), is required for IFN-induced Zbp1 expression.

How does ZBP1 activate RIPK3 in the absence of RIPK1? The simplest explanation is that merely elevating ZBP1 levels in Ripk1−/− MEFs is sufficient to promote association with ‘free’ RIPK3 (i.e., RIPK3 no longer held in check by RIPK1), and this association now clusters sufficient amounts of RIPK3 to trigger kinase activation, phosphorylation of MLKL, and ultimately cell death. In this regard, it is noteworthy that Ripk1−/− MEFs display constitutively-autophosphorylated RIPK3, as do MEFs expressing a RHIM-mutant version of RIPK1 (24). These observations indicate that RIPK1, via a RHIM-RHIM interaction with RIPK3, suppresses RIPK3 activity. In the absence of RIPK1, RIPK3 autophosphorylates and becomes available for interaction with other RHIM-containing proteins, including ZBP1. Under these circumstances, stimuli (such as IFNs) that boost levels of ZBP1 promote RHIM-dependent oligomerization between ZBP1 and RIPK3 to trigger death signaling.

ZBP1 also has direct nucleic acid sensing capacity (20, 31–34), so an alternate, albeit more complex, explanation is that IFN induction of Zbp1 expression alone is insufficient to trigger necroptosis, and that ZBP1 is instead (or additionally) activated by endogenous or pathogen-derived nucleic acids at parturition. Zbp1 mutant knock-in mice that cannot bind nucleic acid (e.g., by mutations in the Zα nucleic acid sensing domains) but still retain the ability to associate with RIPK3 will help distinguish between these alternatives.

An unanticipated outcome from these studies was the finding that, in primary MEFs, IFNs activated necroptosis by notably different mechanisms depending on whether RIPK1 was absent or present. In Fadd−/− MEFs, for example, IFNs drove a pathway of necroptosis that was reliant on PKR and, in remarkable contrast to Ripk1−/− MEFs, required the kinase activity of RIPK1. Moreover, Fadd−/− MEFs did not display either significant basal levels of autophosphorylated RIPK3 or evidence of an IFN-stimulated RIPK3 complex (not shown); instead Fadd−/− MEFs contained a pre-formed ‘necrosome’ complex, composed of phosphorylated forms of RIPK1 and RIPK3, that drove necroptosis upon exposure to IFNs (19). Downstream of RIPK3 activation, we were surprised to observe that, in addition to necroptosis, a pathway of apoptosis reliant on caspase-8 was also induced in Ripk1−/− MEFs. Although RIPK3 has been previously shown to activate caspase-8, such activation was found to require RIPK1 as a bridging adaptor protein necessary for recruitment of caspase-8 to RIPK3. How RIPK3 can activate caspase-8 in the absence of RIPK1 is currently unclear, but suggests the involvement of an as-yet unidentified adaptor(s) that substitutes for RIPK1 in linking RIPK3 to caspase-8. Of interest here, RIPK3 was found to interact with not just caspase-8, but with several other caspases, including caspases-2, −9, and −10 (35). All these caspases have large prodomains, but some - such as caspase-9, with which RIPK3 associates robustly (35) - do not possess the death effector domains (DEDs) required for association with FADD and RIPK1. Thus, RIPK3 can associate with caspases by DED-independent (and therefore likely FADD/RIPK1-independent) mechanisms. In this regard, we observed that RIPK3 activated caspase-8 with notably slower kinetics than it did MLKL (Fig. S1D), indicating that a secondary transcriptional event may be required for caspase-8 activation by RIPK3.

It is noteworthy that, while ablating ZBP1 expression extended the life of Ripk1−/−Caspase-8−/− mice for up to five weeks, eliminating RIPK3 in these mice can protect against lethality for more than a year (4–6). These observations indicate that ZBP1-independent signals later in life trigger RIPK3 when RIPK1 is absent. Activation of the TLR3/4 pathway might represent one such signal, as the TLR3/4 adaptor protein TRIF can directly engage RIPK3 via a RHIM-RHIM association, independent of its capacity to stimulate IFN production (26, 27). It is also likely that other as-yet undescribed mechanisms of RIPK3 activation likely exist; in this regard, Silverman and colleagues have shown the existence of RHIM-like sequences in the Drosophila proteins PGRP-LC, PGRP-LE and IMD that can functionally reconstitute RHIM-based signaling in mammalian cells (36). Whether mammalian proteins with similar ‘cryptic RHIMs’ function to trigger RIPK3 in adulthood awaits discovery.

In aggregate, our results implicate IFNs as dominant triggers of RIPK3 activation when RIPK1 is absent, and demonstrate that IFNs activate RIPK3 by inducing expression of ZBP1. RIPK1 protects cells form IFN-mediated toxicity by restraining RIPK3 activity and preventing RIPK3 from associating with ZBP1. Thus, RIPK1 functions in development as a ‘homeostatic harbor’ by protecting against lethal IFN-mediated cell death signaling without impeding beneficial host defense responses induced by these cytokines upon exposure to viruses and microbes during and after parturition.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

Interferons induce RIPK3-dependent cell death in the absence of RIPK1.

The interferon-stimulated gene product ZBP1 drives cell death in Ripk1−/− cells.

ZBP1 and interferon signaling contribute to perinatal lethality of Ripk1−/− mice.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Anthony Lerro, Lauren Heisey and Simon Tarpanian for animal husbandry and Maria Shubina for help preparing figures.

Funding. This work was supported by NIH grants CA168621, CA190542 and AI135025 to S.B, Public Health Service Grant DP5OD012198 to W.J. K., and NIH grants AI44828 and CA231620 to D.R.G. Additional funds were provided by NIH Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA006927 to the Fox Chase Cancer Center.

References

- 1.Stanger BZ, Leder P, Lee TH, Kim E, and Seed B. 1995. RIP: a novel protein containing a death domain that interacts with Fas/APO-1 (CD95) in yeast and causes cell death. Cell 81: 513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsu H, Huang J, Shu HB, Baichwal V, and Goeddel DV. 1996. TNF-dependent recruitment of the protein kinase RIP to the TNF receptor-1 signaling complex. Immunity 4: 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelliher MA, Grimm S, Ishida Y, Kuo F, Stanger BZ, and Leder P. 1998. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-kappaB signal. Immunity 8: 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Rodriguez DA, Cripps JG, Quarato G, Gurung P, Verbist KC, Brewer TL, Llambi F, Gong YN, Janke LJ, Kelliher MA, Kanneganti TD, and Green DR. 2014. RIPK1 blocks early postnatal lethality mediated by caspase-8 and RIPK3. Cell 157: 1189–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaiser WJ, Daley-Bauer LP, Thapa RJ, Mandal P, Berger SB, Huang C, Sundararajan A, Guo H, Roback L, Speck SH, Bertin J, Gough PJ, Balachandran S, and Mocarski ES. 2014. RIP1 suppresses innate immune necrotic as well as apoptotic cell death during mammalian parturition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 7753–7758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rickard JA, O’Donnell JA, Evans JM, Lalaoui N, Poh AR, Rogers T, Vince JE, Lawlor KE, Ninnis RL, Anderton H, Hall C, Spall SK, Phesse TJ, Abud HE, Cengia LH, Corbin J, Mifsud S, Di Rago L, Metcalf D, Ernst M, Dewson G, Roberts AW, Alexander WS, Murphy JM, Ekert PG, Masters SL, Vaux DL, Croker BA, Gerlic M, and Silke J. 2014. RIPK1 regulates RIPK3-MLKL-driven systemic inflammation and emergency hematopoiesis. Cell 157: 1175–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishii KJ, Kawagoe T, Koyama S, Matsui K, Kumar H, Kawai T, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O, Takeshita F, Coban C, and Akira S. 2008. TANK-binding kinase-1 delineates innate and adaptive immune responses to DNA vaccines. Nature 451: 725–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandal P, Berger SB, Pillay S, Moriwaki K, Huang C, Guo H, Lich JD, Finger J, Kasparcova V, Votta B, Ouellette M, King BW, Wisnoski D, Lakdawala AS, DeMartino MP, Casillas LN, Haile PA, Sehon CA, Marquis RW, Upton J, Daley-Bauer LP, Roback L, Ramia N, Dovey CM, Carette JE, Chan FK, Bertin J, Gough PJ, Mocarski ES, and Kaiser WJ. 2014. RIP3 induces apoptosis independent of pronecrotic kinase activity. Mol Cell 56: 481–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez DA, Weinlich R, Brown S, Guy C, Fitzgerald P, Dillon CP, Oberst A, Quarato G, Low J, Cripps JG, Chen T, and Green DR. 2016. Characterization of RIPK3-mediated phosphorylation of the activation loop of MLKL during necroptosis. Cell Death Differ 23: 76–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newton K, Sun X, and Dixit VM. 2004. Kinase RIP3 is dispensable for normal NF-kappa Bs, signaling by the B-cell and T-cell receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Mol Cell Biol 24: 1464–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salmena L, Lemmers B, Hakem A, Matysiak-Zablocki E, Murakami K, Au PY, Berry DM, Tamblyn L, Shehabeldin A, Migon E, Wakeham A, Bouchard D, Yeh WC, McGlade JC, Ohashi PS, and Hakem R. 2003. Essential role for caspase 8 in T-cell homeostasis and T-cell-mediated immunity. Genes Dev 17: 883–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfeffer K, Matsuyama T, Kundig TM, Wakeham A, Kishihara K, Shahinian A, Wiegmann K, Ohashi PS, Kronke M, and Mak TW. 1993. Mice deficient for the 55 kd tumor necrosis factor receptor are resistant to endotoxic shock, yet succumb to L. monocytogenes infection. Cell 73: 457–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller U, Steinhoff U, Reis LF, Hemmi S, Pavlovic J, Zinkernagel RM, and Aguet M. 1994. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science 264: 1918–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang S, Hendriks W, Althage A, Hemmi S, Bluethmann H, Kamijo R, Vilcek J, Zinkernagel RM, and Aguet M. 1993. Immune response in mice that lack the interferon-gamma receptor. Science 259: 1742–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meraz MA, White JM, Sheehan KC, Bach EA, Rodig SJ, Dighe AS, Kaplan DH, Riley JK, Greenlund AC, Campbell D, Carver-Moore K, DuBois RN, Clark R, Aguet M, and Schreiber RD. 1996. Targeted disruption of the Stat1 gene in mice reveals unexpected physiologic specificity in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Cell 84: 431–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikawa H, Ma Z, and Barber GN. 2009. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. Nature 461: 788–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun Q, Sun L, Liu HH, Chen X, Seth RB, Forman J, and Chen ZJ. 2006. The specific and essential role of MAVS in antiviral innate immune responses. Immunity 24: 633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen P, Nogusa S, Thapa RJ, Shaller C, Simmons H, Peri S, Adams GP, and Balachandran S. 2013. Anti-CD70 Immunocytokines for Exploitation of Interferon-gamma-Induced RIP1-Dependent Necrosis in Renal Cell Carcinoma. PLoS One 8: e61446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thapa RJ, Nogusa S, Chen P, Maki JL, Lerro A, Andrake M, Rall GF, Degterev A, and Balachandran S. 2013. Interferon-induced RIP1/RIP3-mediated necrosis requires PKR and is licensed by FADD and caspases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: E3109–3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thapa RJ, Ingram JP, Ragan KB, Nogusa S, Boyd DF, Benitez AA, Sridharan H, Kosoff R, Shubina M, Landsteiner VJ, Andrake M, Vogel P, Sigal LJ, tenOever BR, Thomas PG, Upton JW, and Balachandran S. 2016. DAI Senses Influenza A Virus Genomic RNA and Activates RIPK3-Dependent Cell Death. Cell Host Microbe 20: 674–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nogusa S, Thapa RJ, Dillon CP, Liedmann S, Oguin TH 3rd, Ingram JP, Rodriguez DA, Kosoff R, Sharma S, Sturm O, Verbist K, Gough PJ, Bertin J, Hartmann BM, Sealfon SC, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES, Lopez CB, Thomas PG, Oberst A, Green DR, and Balachandran S. 2016. RIPK3 Activates Parallel Pathways of MLKL-Driven Necroptosis and FADD-Mediated Apoptosis to Protect against Influenza A Virus. Cell Host Microbe 20: 13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanden Berghe T, Hassannia B, and Vandenabeele P. 2016. An outline of necrosome triggers. Cell Mol Life Sci 73: 2137–2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Upton JW, Shubina M, and Balachandran S. 2017. RIPK3-driven cell death during virus infections. Immunol Rev 277: 90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newton K, Wickliffe KE, Maltzman A, Dugger DL, Strasser A, Pham VC, Lill JR, Roose-Girma M, Warming S, Solon M, Ngu H, Webster JD, and Dixit VM. 2016. RIPK1 inhibits ZBP1-driven necroptosis during development. Nature 540: 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J, and Chen ZJ. 2014. Innate immune sensing and signaling of cytosolic nucleic acids. Annu Rev Immunol 32: 461–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaiser WJ, Sridharan H, Huang C, Mandal P, Upton JW, Gough PJ, Sehon CA, Marquis RW, Bertin J, and Mocarski ES. 2013. Toll-like receptor 3-mediated necrosis via TRIF, RIP3, and MLKL. J Biol Chem 288: 31268–31279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He S, Liang Y, Shao F, and Wang X. 2011. Toll-like receptors activate programmed necrosis in macrophages through a receptor-interacting kinase-3-mediated pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 20054–20059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin J, Kumari S, Kim C, Van TM, Wachsmuth L, Polykratis A, and Pasparakis M. 2016. RIPK1 counteracts ZBP1-mediated necroptosis to inhibit inflammation. Nature 540: 124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuriakose T, Zheng M, Neale G, and Kanneganti TD. 2018. IRF1 Is a Transcriptional Regulator of ZBP1 Promoting NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Cell Death during Influenza Virus Infection. J Immunol 200: 1489–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramsauer K, Farlik M, Zupkovitz G, Seiser C, Kroger A, Hauser H, and Decker T. 2007. Distinct modes of action applied by transcription factors STAT1 and IRF1 to initiate transcription of the IFN-gamma-inducible gbp2 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 2849–2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, and Mocarski ES. 2012. DAI/ZBP1/DLM-1 complexes with RIP3 to mediate virus-induced programmed necrosis that is targeted by murine cytomegalovirus vIRA. Cell Host Microbe 11: 290–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuriakose T, Man SM, Malireddi RK, Karki R, Kesavardhana S, Place DE, Neale G, Vogel P, and Kanneganti TD. 2016. ZBP1/DAI is an innate sensor of influenza virus triggering the NLRP3 inflammasome and programmed cell death pathways. Science immunology 1(2). pii: aag2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koehler H, Cotsmire S, Langland J, Kibler KV, Kalman D, Upton JW, Mocarski ES, and Jacobs BL. 2017. Inhibition of DAI-dependent necroptosis by the Z-DNA binding domain of the vaccinia virus innate immune evasion protein, E3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114: 11506–11511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo H, Gilley RP, Fisher A, Lane R, Landsteiner VJ, Ragan KB, Dovey CM, Carette JE, Upton JW, Mocarski ES, and Kaiser WJ. 2018. Species-independent contribution of ZBP1/DAI/DLM-1-triggered necroptosis in host defense against HSV1. Cell death & disease 9: 816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun X, Lee J, Navas T, Baldwin DT, Stewart TA, and Dixit VM. 1999. RIP3, a novel apoptosis-inducing kinase. J Biol Chem 274: 16871–16875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kleino A, Ramia NF, Bozkurt G, Shen Y, Nailwal H, Huang J, Napetschnig J, Gangloff M, Chan FK, Wu H, Li J, and Silverman N. 2017. Peptidoglycan-Sensing Receptors Trigger the Formation of Functional Amyloids of the Adaptor Protein Imd to Initiate Drosophila NF-kappaB Signaling. Immunity 47: 635–647 e636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Basagoudanavar SH, Thapa RJ, Nogusa S, Wang J, Beg AA, and Balachandran S. 2011. Distinct roles for the NF-kappa B RelA subunit during antiviral innate immune responses. J Virol 85: 2599–2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.