Abstract

Tissue regeneration requires scaffolds that exhibit mechanical properties similar to the tissues to be replaced while allowing cell infiltration and extracellular matrix production. Ideally, the scaffolds’ porous architecture and physico-chemical properties can be precisely defined to address regenerative needs. We thus developed techniques to produce hybrid fibers coaxially structured with a polycaprolactone core and a 4-arm, polyethylene glycol thiol-norbornene sheath. We assessed the respective effects of crosslink density and sheath polymer size on the scaffold architecture, physical and mechanical properties, as well as cell-scaffold interactions in vitro and in vivo. All scaffolds displayed high elasticity, swelling and strength, mimicking soft tissue properties. Importantly, the thiol-ene hydrogel sheath enabled tunable softness and peptide tethering for cellular activities. With increased photopolymerization, stiffening and reduced swelling of scaffolds were found due to intra- and inter- fiber crosslinking. More polymerized scaffolds also enhanced the cell-scaffold interaction in vitro and induced spontaneous, deep cell infiltration to produce collagen and elastin for tissue regeneration in vivo. The molecular weight of sheath polymer provides an additional mechanism to alter the physical properties and biological activities of scaffolds. Overall, these robust scaffolds with tunable elasticity and regenerative cues offered a versatile and effective platform for tissue regeneration.

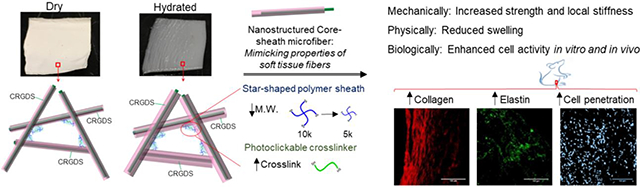

Graphical Abstract

Tissue-regenerative scaffolds made of microfibers coaxially structured with polycaprolactone sheathed by 4-arm thiol-norbornene display high elasticity, swelling and strength, and show deep cell infiltration and extracellular matrix production in vivo, mimicking soft tissues.

1. Introduction

Tissue regenerative scaffolds play an important role in improving existing therapies for a number of injured or degenerative tissues, such as blood vessel, skin, cartilage, ligament, tendon and muscle tissues.1–6 To produce these scaffolds, electrospinning and hydrogel systems are both widely used.1 Electrospinning allows the generation of micro-/nano- fibrous scaffolds showing physical similarities with the extracellular matrix (ECM) found in native tissues.1,7 Specifically, electrospun fibers provide high surface-to-volume ratios for cellular-scale topographical cues, as well as high porosity with interconnected pore network for the transportation of nutrients and signal molecules.7,8 However, electrospun fibers often form dense, hydrophobic mats, resulting in cell-impenetrable scaffolds.9 To overcome this issue, patterned electrospun multilevel structural fibrous membranes have recently been developed, showing enhanced cell infiltration, proliferation, and attachment.10 Another method of improving cell penetration has been accomplished by increasing the inter-fiber spacing or porosity by adding sacrificial pore-forming agents.9 These scaffolds with large pores were used to seed and culture cells in 3D, but their capacity of attracting cells in the body for tissue regeneration is yet to be revealed. A regenerative scaffold requires not only proper pore architecture, but also physico-chemical properties that provide sufficient migratory, adhesive and/or differentiating cues for cell infiltration and matrix production. To this end, we have fabricated electrospun fibers with the surfaces characterized by a versatile hydrogel material, 4-arm, end-functionalized polyethylene glycol norbornene (PEG-NB), which can define appropriate physico-chemical microenvironments to modulate cellular activities.

To take advantage of diverse properties provided by distinct materials in the scaffold construction, previous studies have attempted to form scaffolds by mixing or layering polymers with drastically different properties, such as hydrophobic/hydrophilic polymers.7 However, the adhesions or interactions between these blended or layered materials9 are often low, leading to undefined material defects in heterogeneous scaffolds and thus compromised stability and reduced strength.11 Coaxial electrospinning provides a unique approach to construct a well-structured polymer mixture, wherein the polymers are highly interactive at the nanoscale to bring about novel properties.8 In particular, coaxial core-shell nano-/micro- fibers using two dissimilar material types present high potentials for regenerative applications, through exploiting materials’ properties to address respective needs of materials strength and bioactivity.12,13

This study was designed to fabricate strong, porous hydrogel scaffolds with controllable matrix stiffness, swelling and biochemical ligands, which was used to further examine the influence of design factors on cell infiltration and matrix production. We achieved the goal with a unique fiber structure consisting of strong biodegradable polycaprolactone (PCL) core and 4-armed PEG thiol-ene hydrogel sheath. Due to its mechanical strength, hydrophobic PCL has been used in myriad tissue engineering applications such as vascular regeneration. However, it lacks cell-recognition sites and tends to attract platelets and plasma proteins.8 PEG with super-hydrophilic chains prevents protein adsorption via its steric barrier14, but it is mechanically weak. Thus, in our design, the PCL core provides the mechanical strength and stability of coaxial fiber scaffolds, while the sheath ensures mimetic viscoelasticity and tunable physicochemical properties. In particular, the photo-clickable, PEG thiol-ene sheath enables a hydrogel environment with well-controlled softness via the reactivity of intra- and inter- fiber, and covalent tethering of cell-interactive peptides. The effects of PEG-NB molecular weight and crosslinking degree on the cellular adhesion, infiltration and matrix production were assessed in the developed scaffolds made of coaxial PCL/ PEG thiol-ene fibers.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

All polymers and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO) unless specified otherwise.

2.2. Fabrication of coaxial fibers

The apparatus used for obtaining coaxial fibers was developed in-house. The core hydrophobic polymer solution was passed through the inner needle of 22 G (0.71 mm in internal diameter), while the sheath hydrophilic polymer solution was passed through the outer needle of 18 G. A dual syringe holder was used to place the syringes loaded with polymer solutions. This design allows the solutions to be extruded simultaneously. Polymer solutions of 1.8 wt % concentration of PCL and 3 wt % 4-arm PEG-NB 5 kDa (synthesized in-house) or 4-arm PEG-NB 10 kDa were prepared by dissolving a predetermined amount of PCL, PEG-NB 5 kDa or PEG-NB 10 kDa, PEG-SH (JenKem Technology, Dallas, TX), PEO, and Irgacure 2959 (Ciba Speciality Chemicals, Basel, Switzerland) in 1,1,1,3,3,3 hexafluoro-2-propanaol (HFP, CovaChem, Loves Park, IL). Fig. S8 shows the composition of the different polymers used for the hydrogel’s fibers. The solutions obtained after stirring for 30 min – 3 h were loaded in 5 mL syringes connected to the positive terminal of a high voltage ES30P 10 W power supply (Gamma High Voltage Research, Ormond Beach, FL). The core polymer solution was extruded at 0.8 mL/h and the sheath polymer solution at 1 mL/h using syringe pumps (Pump 11 Plus, Harvard Apparatus, Boston, MA) and subjected to an electric potential of 11 kV. The fibers were deposited onto a grounded static aluminum substrate placed at a distance of 15 cm perpendicular to the needle. The obtained samples were stored at room temperature until further use.

2.3. Crosslinking of fibrous scaffolds with UV polymerization

The scaffolds composed of coaxial fibers were subjected to vacuum for 15 min for oxygen removal using a glovebox (Vacuum Atmospheres Company, OMNI-LAB, Hawthorne, CA) containing argon. After that, the scaffolds were cross-linked by UV light (supplied power ~ 5 mV/cm2) for varied UV times. Immediately after the crosslinking process, fibrous scaffolds were rinsed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and used for mechanical characterization (tensile and rheometry testing), or subsequently lyophilized for 48 h to obtain dry samples for ATR-FTIR spectroscopy, thermal analyses, and SEM. For cell and animal studies, the samples were treated with RGD 5 mM after PBS rinse. The clickable thiol-ene PEG photo-polymerization occurs through a reaction between the “ene” groups present in the 4-arm PEG-NB norbornene rings and the thiol groups of the poly(ethylene glycol) dithiol (PEG-SH), which is used as the cross-linker. A step-growth mechanism leads to a highly homogenous distribution in cross-links, thus imparting tunable substrate stiffness through UV exposure time. For most characterization and biological studies, two UV doses were used by changing the UV exposure time: 10 min UV polymerization for low UV dose, and 60 min for high UV dose.

2.4. Electron microscopy imaging of fiber morphology and structure

Electrospun fibers were imaged with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron spectroscopy (TEM). To investigate fiber morphology in the scaffold, the aluminum substrates coated with the electrospun fibers were mounted on brass stubs and sputter coated with Pt/Pd (BIO-RAD, SEM coating unit PS3, Assing S.p.a, Rome, Italy). Observations were made at 5 kV by using a Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM, Supra 40, Zeiss, Germany). Both crosslinked electrospun fibers in both dry and wet states were analyzed. The water-swollen fibers in the wet state were prepared by soaking fibers after cross-linking in PBS for 24 h and lyophilizing for 48 h to preserve the fiber’s structure and morphology. To analyze the average pore size and porosity of fibers, three images were taken in different locations of each sample, and measurements were averaged using NIH ImageJ software. In addition to SEM, we also used optical imaging to observe fibers in both dry state of uncrosslinked fibers and wet state of cross-linked fibers. Fiber diameter and sheath increase after hydration were calculated using ImageJ from the obtained images. Three images were taken in different locations of each sample, and roughly 100 fiber diameters and sheath thicknesses were measured and averaged using ImageJ.

TEM was used to image the nanostructure of the coaxial fibers. A FEI TecnaiTM T12 SpiritBT (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) was used with a CCD camera AMT XR41, operated at 100 kV. The electrospun fiber samples for TEM were prepared by directly depositing the as-spun fiibers on carbon-coated TEM grids. For sheath-to-fiber diameter ratio analysis, three images were taken in different locations of each sample, and roughly 100 fiber diameters and sheath thicknesses were measured and averaged using ImageJ. Results were presented as mean ± standard deviation.

2.5. Physical, mechanical and chemical characterizations of coaxial fiber materials

2.5.1. Swelling and water retention capacity of coaxial fibers

To determine the swelling capability, the percentage of water retained was measured after 10, 30, 45, and 60 min of cross-linking of the coaxial fibers. The samples were submersed in deionized water for 24 h, then taken out and removed the excess water before being weighed. After that, the samples were dried by placing them into a vacuum chamber for 24 h, and weighed again. Water retention capacity was determined by the weight increase using Equation (1).

| (1) |

Equation (1): Water retention capacity, where w is the weight of each specimen after submersion, or wet weight, and wd is the weight of the specimen in its dry state after submersion and drying.

2.5.2. Rheometry testing

The viscoelastic properties of coaxial scaffolds were investigated under shear deformation using the ARES or ARG2 rheometer (TA Instrument, New Castle, DE). The ARES is designed to measure the expended torque. Samples were analyzed on ARES using the plate geometry (diameter = 18 mm; gap set between 0.02 and 0.07 mm). Strain sweep measurements spanning from 0.1 to 5% strain were conducted at 10 points each decade of strain (e.g., 0.1–1%). Frequency sweeps were conducted at a stress–strain range of constant oscillation frequency. Oscillatory frequency sweep tests were conducted with logarithmic step increases between 0.1 and 50 Hz to identify the linear region for all scaffolds. The storage modulus (G’) and loss modulus (G”) of scaffolds as well as tan δ (tan δ = G’/G”) were determined in the linear viscoelastic region (LVR). Using G’ and G”, the complex storage modulus (G*) can be calculated using G* = G’+ iG”. Shear stress was determined in response to constant strain application, reflecting the difference in material viscosity. In order to avoid sample slipping during rheometry measurement, the glass slides were treated for sample attachment. Briefly, slides are immersed in acetone, placed in an ultrasound bath for 15–20 min, washed with ethanol twice, and dried. After this, the glass slides are immersed in a solution containing 0.45 mL of 3-trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate, 2.4 mL of a 1:10 solution of Glacial Acetic Acid: DI Water, and 80 mL of ethanol. Then, the slides are treated in the oxygen plasma chamber at 70 W for 2 minutes. After a couple hours, the slides are rinsed in ethanol twice, and dried before they are used to collect microfibers for rheometry measurements. The slides are stored in the −20 °C freezer for future use.

2.5.3. Tensile testing

Dogbone-shaped fiber samples with dimensions of 63 mm × 3 mm were tested for their tensile strength. Dog-bone samples were used to ensure the highest probability that the samples failed due to maximum tensile loading rather than improper loading or a pre-existing defect in the material. To prepare dogbone-shaped specimens, the dry electrospun fiber scaffold was cut with a dogbone sample cutter after UV light polymerization (Fig. S1). The samples were then hydrated by soaking into PBS for 24 h before tensile tests. A water chamber was used to assure hydration of the samples during the test. Load–elongation measurement was carried out at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min, 25 °C temperature, and relative humidity of 65%. A 250 N load cell (MTS Systems Corp) was used. The percentage of elongation at break (%) was measured using a MTS Insight electromechanical testing system (MTS Systems Corp., Eden Prairie, MN). The Young’s Modulus was measured from the stress-strain curves obtained from tensile testing. Briefly, Young’s Modulus was calculated as the uniaxial stress divided by the strain, measured at 10% of strain (linear region).

2.5.4. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

Attenuated total reflection-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) measurements were carried out on cross-linked fibrous scaffolds using a Perkin Elmer Spectrum One Spectrophotometer equipped with a diamond probe. An average of 4 acquisitions were obtained at a resolution of 4 cm−1. The spectrum of the samples was recorded in the spectral region from 600 to 4000 cm−1.

2.5.5. Thermal analysis - thermogravimetric analysis and differential scanning calorimetry analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the fibers was performed using a Mettler TG50 thermobalance under flushing nitrogen (100 mL/min). About 10 mg of the samples were placed in a nitrogen atmosphere and heated at 10 °C min−1 starting at the room temperature and up to 700 °C. Both cross-linked fibers and fiber meshes were analyzed. The decomposition temperature (Td) corresponding to the temperature associated with the maximum mass loss rate was determined. Pure polymers, including PEG-NB 5k, PEG NB 10k, PEO (Mn = 400,000), and PCL (Mn = 80,000, in pellet and fiber forms), were used as reference materials.

Differential scanning calorimeter (DSC Q20, TA Instruments, USA) was performed under flushing nitrogen (100 mL/min). Specifically, about 10 mg of the samples was placed in a heating chamber, and constant nitrogen gas flow and heating-cooling-heating cycles were performed. Each sample was first heated from 5°C to 100°C with an incremental rate of 10 °C min−1 to eliminate the thermal history of the materials. The samples were then fast cooled to 5°C at a cooling rate of 25 °C min−1 and reheated for a second scan up to 100°C at a rate of 10°C min−1. The same reference materials used in TGA were included in DSC measures. The melting behavior of PEG-NB species after crosslinking was determined by monitoring the endothermic melting peaks. The respective proportion in the coaxial PCL/PEG-NB samples was determined from the intensity of PCL melting peak in the second scan. Specifically, the enthalpy of fusion related to PCL melting for pure PCL samples and PCL/PEG-NB coaxial samples were quantitatively determined by calculating the area of the endothermic melting peak. The crystallinity degree of PCL (αPCL) was determined by comparing the enthalpy of fusion of pure PCL fibers (ΔHPCL) with the theoretical value of a 100% crystalline PCL (ΔH100%), which equals to 139.4 J/g.15 Thus, αPCL = 100 * (ΔHPCL / ΔH100%). Under the assumption that crystallinity degree of PCL (αPCL) remained constant in the case of coaxial fibers, αPCL was used to determine the fraction of PCL in the coaxial samples.

2.6. Cell attachment and compatibility of coaxial fibers

Bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells (bPAECs) from Lonza Inc. (Basel, Switzerland) were seeded on top of coaxial fiber scaffolds with a seeding density of 5 × 104 cells/cm2 at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. Cells at passage 9 were used. Treated glass slides were also used for cell attachment studies. Before cell seeding, the coaxial fiber scaffolds were treated with 5 mM CRGDS (GenScript Inc., Piscataway, NJ), which was covalently bonded to the PEG-NB through UV light (5 min of UV exposure). Then, the scaffold samples were rinsed with PBS to remove unattached RGD, sterilized with 70% ethanol for 15 min, and rinsed again three times with sterile PBS. The cell culture medium was composed of MEM Eagle D-Valine medium modified with 4 mM L-Glutamine (US Biological Life Sciences, Marblehead, MA), 20% FBS (Corning, 35–0101-CV), 50 μg/mL gentamicin, and 70 μg/mL heparin. To evaluate cell attachment and morphology, the cell-seeded scaffolds were rinsed with PBS after 24 h of cell seeding, fixed using 4% formaldehyde, and stained with DAPI and F-actin. The stained cells were examined with appropriate filters using a fluorescent microscope at 10x and 40x magnification. The number of cells attached to each scaffold was determined using ImageJ software.

2.7. Materials implantation and explant evaluation

The animal experiments were approved and performed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, approval number: 1407.02) at the University of Colorado and complied with the NIH’s Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Five groups of scaffold samples (n=5–7 for each group) were evaluated: PCL/PEG-NB 5 kDa and PCL/PEG-NB 10 kDa coaxial fiber scaffolds polymerized with low or high UV dose, and PCL fiber scaffold. The prepared fibrous materials were cut into circular disks (1 cm diameter). Prior to implantation, materials were treated as those for in vitro cell culture. The sample evaluation was performed on Sprague Dawley rats at 8–9 months old at the time of the implantation, weighing ~ 400 grams. The rats were purchased from ENVIGO (Indianapolis, IN). Anesthesia in rats was induced with 5% isoflurane gas (Vet One) and maintained with 2% isoflurane gas. Surgical site was cleaned and disinfected with povidone-iodine (Medline Industries Inc, Northfield, IL). Rats were given isoflurane anesthesia at 5% per liter O2 until fully anesthetized. Following anesthesia, mid ventral skin was shaved, washed with ethanol, and then coated with betadine. Rats were transferred to a procedural table that was cleaned with 70% ethanol solution and covered with a clean disposable towel. A sterile disposable blade was used to make the incision and create a 1.5 cm × 2 cm subcutaneous pocket. Material samples were then placed on top of the subcutaneous musculature. The incision was then closed using 9 mm autoclips (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CN). Finally, 50 μL of 1:1 ratio of lidocaine and bupivacaine mixture (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL) were injected between autoclips away from the subcutaneous pockets containing samples. After the implantation procedure, rats were moved to a clean cage over a heating pad set to 37˚C. Their movements and signs of distress were closely monitored for the first 24 h. The samples were retrieved after 7 days of the implantation.

The explanted samples were embedded with OCT and cryosectioned into 8–10 μm thick sections. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s Trichrome, which were performed by the Histology Core at University of Colorado. Imaging was performed with a light microscope (Nikon Microscopy). To determine materials-induced inflammation, immunofluorescent staining with CD68 to detect the macrophage presence was used with DAPI counterstain. Briefly, the explanted frozen samples were blocked with 10% wt albumin, then applied with CD68 (6A324, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) primary antibody (1:100 in TBS containing 1% albumin), and finally applied with secondary antibody mIgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) with a dilution of 1:100 in TBS.

2.8. Dual-modality multiphoton imaging

To determine the matrix production in scaffold implants in rats, dual modal multiphoton imaging, including second harmonic generation (SGH) and two-photon excitation fluorescence (TPEF), was used to respectively investigate the fibrillar collagen and elastin contents. The sectioned samples were mounted on glass slides, submerged in PBS, and covered with a coverslip. For SGH and TPEF imaging, a multiphoton laser scanning microscope system (Radiance 2000 MP, Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc, Hercules, CA) was used with 40x magnification (n.a. = 1.30), oil immersion objective. A femtosecond pulsed laser system tuned to 860 nm wavelength was used for excitation (Spectra-Physics, MaiTai wideband, mode-locked Ti:Sapphire laser system). The response signal was split at 455 nm using a dichroic mirror (AT455 DC, Chroma Technology Corp, Bellows Falls, VT). The SHG signal (400–455 nm) for collagen and the TPEF signal (460–610 nm) for elastin were captured simultaneously using the direct detector system. A 535/150 nm BrightLine bandpass filter was used for elastin TPEF capture. Images 1024×1024 pixels (305×305 microns) were collected at 50 lps. Each image was generated using Kalman averaging over 3 frames.

2.9. Data analysis and statistics

Data were statistically analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance test (ANOVA) with a sample size of at least 3 (n ≥ 3) for each set. Student’s t test was then used to compare the means of each individual group. The statistical significance levels were set at: p < 0.05 (* or #), p < 0.01 (** or ##), and p < 0.001 (*** or ###), for 95%, 99%, and 99.9% confidence, respectively. Results were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Error bars on all the histogram charts represent the standard deviation of the mean based on the total number of samples.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Morphology of the hybrid coaxial fibers

The morphology of fabricated fiber scaffolds was characterized by electron microscopy (Fig. 1). Fig. 1A shows the TEM images of the coaxial fibers with the core made of PCL and the sheath made from PEG-NB 5k or PEG-NB 10k. It demonstrates the successful formation of continuous coaxial PCL/PEG thiol-ene fibers. For both coaxial materials, we applied the flow rates of 0.8 mL/h and 1 mL/h for the core and sheath prepolymer fluids, respectively. The formation of continuous fibers was through our parametric studies of the coaxial electrospinning process. Fig. S2A illustrates another set of study, where the sheath fluid rate was increased to 1.3–1.4 mL/h, resulting in the discontinuity of the core fiber structure. This might be due to the high shear force produced by the more viscous sheath solution, longitudinally stretching the less viscous core solution and causing breakages in the core structure by rupturing the core material cohesion.

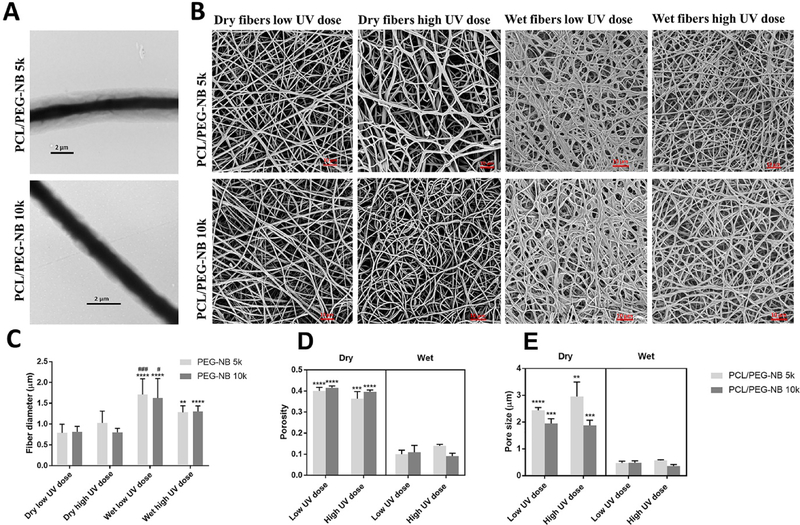

Fig. 1.

Representative electron microscopy images and quantitative analyses of coaxially-structured fibers. (A) TEM images of as-spun coaxial fibers. (B) SEM images of coaxial fiber scaffolds, which were polymerized at different UV doses and stored in either dry or hydrated conditions. (C) Fiber diameter before and after hydration of coaxial blends. ‘*’ comparing vs. dry, ‘#’ comparing vs. wet high UV dose. (D) Porosity and (E) Pore size of coaxial blends before and after hydration. ‘*’ comparing vs. dry PCL/PEG-NB. The coaxial microfibers include: PCL/PEG-NB 5k and PCL/PEG-NB 10k. (A): scale bar = 2 μm.

Table 1 shows the fiber diameter, core diameter, and sheath thickness measured from the TEM images, together with the sheath-to-fiber diameter ratios. To calculate the average sheath-to-fiber diameter ratio of fibers, the average sheath thickness was divided by the average fiber diameter. To obtain the standard deviation of this ratio, we reported the standard deviations for the sheath-to-fiber diameter ratios from individual fibers. Table 1 demonstrates that the sheath-to-diameter ratio for PCL/PEG-NB 5k is larger than PCL/PEG-NB 10k, while their average fiber diameters are similar. The ratio difference is due to a thicker sheath and smaller-sized core of PCL/PEG-NB 5k, compared to PCL/PEG-NB 10k. This might be related to the difference in the core-sheath interactions. The molecular interactions between core and sheath solutions may explain the finding about thicker sheath and higher sheath-to-diameter ratio in PCL/PEG-NB 5k fibers compared to PCL/PEG-NB 10k fibers. Compared to PCL/PEG-NB 10k, the presence of a larger number of shorter chains in PEG-NB 5k sheath could initiate a higher level of non-covalent bonding (stronger interaction between the core and the sheath solutions), leading to a thicker PEG-NB 5k sheath in PCL/PEG-NB 5k fibers. The polymer solution viscosity and solvent evaporation rate might play additional roles.16–18 It is also found that the sheath thickness is not completely homogenous through coaxial fibers, which might be caused by varied surface energies between the core and sheath19, affecting their adhesions.

Table 1.

Sheath-to-fiber diameter ratio of coaxial fibers.

| Scaffold material | Fiber diameter [μm] | Core diameter [μm] | Sheath thickness [μm] | Sheath-to-fiber diameter ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL/PEG-NB 5k | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| PCL/PEG-NB 10k | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.3 |

Fig. 1B shows the SEM images of the coaxial fibers polymerized with varied UV dose in dry or wet states. Quantitative analysis results are shown in Fig. 1C–E. The coaxial fibers of PCL/PEG-NB 5k and PCL/PEG-NB 10k display similar diameters, porosity and pore size in dry or wet states. For both coaxial fibers, the diameters of wet fibers are significantly larger than dry fibers, due to water adsorption (Fig. 1C). Consequently, the swollen fiber scaffolds display decreased pore size and porosity, with respect to the dry scaffolds (Fig. 1D–E). Regarding the UV dose effect, results demonstrate that a lower UV dose (10 min of polymerization) leads to a larger fiber diameter and thus higher water retention in the coaxial fibers for PCL/PEG-NB 5k and 10k (Fig. 1C). This might be due to fewer interconnected PEG-NB molecules in less cross-linked fibers, which permit more water penetration and yield thicker fibers. Also, coaxial fiber swelling is only attributed to the hydrophilic sheath. Table 2 shows the sheath increase after hydration, confirming the polymerization effect on fiber swelling. The SEM image of PCL fibers is shown in Fig. S2B. Interestingly, the fiber diameter, pore size and porosity of PCL only fibers are much smaller than those of dry coaxial fibers. Fiber diameter results from optical images agree with those obtained from SEM images, and they are shown in Fig. S2C.

Table 2.

Sheath increase after hydration of coaxial fibers.

| UV dose | PCL/PEG-NB 5k sheath increase [%] | PCL/PEG-NB 10k sheath increase [%] |

|---|---|---|

| Wet low UV dose | 167 ± 38% | 193 ± 31% |

| Wet high UV dose | 111 ± 66% | 114 ± 142% |

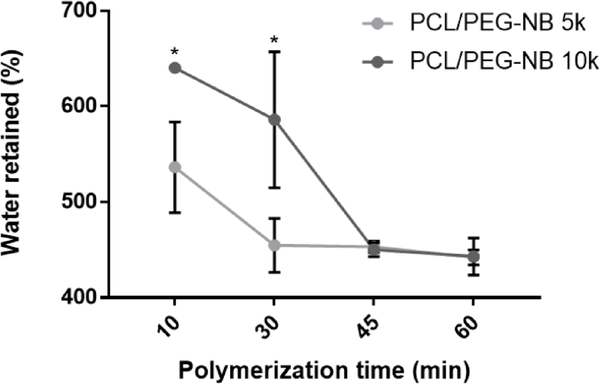

3.2. The coaxial fiber scaffolds display hydrogel-like swelling behaviors, varying with polymerization

To characterize the swelling behaviors of coaxial fiber scaffolds, the water retention of scaffolds polymerized by varied UV doses (10, 30, 45 and 60 min of polymerization) was measured. Results regarding the UV dose effect on scaffold swelling (Fig. 2) are consistent with those from individual fiber swelling (Fig. 1C). Increased UV dose decreases the water retention of scaffolds, with the lowest dose yielding highest water retention. Both fiber swelling and increased water retained in the interfibrillar space could account for this water retention. However, water retained in the interfibrillar space might be quite limited, because Fig. 1D–E shows that both PCL/PEG-NB 5k and 10k scaffolds display lower pore size and porosity after hydration, resulting in denser fiber nets. Interestingly, the water retention of PCL/PEG-NB 10k is higher than PCL/PEG-NB 5k at the UV doses of 10 min and 30 min. This may be related to the longer reactive arms of the higher molecular weight PEG-NB 10k, which make polymer chains more spatially separated, creating more spaces for water retention. Another possible explanation is that PEG-NB 5k presents twice as many reactive norbornene groups as PEG-NB 10k, resulting in higher crosslink density. After 45 min, the polymerization in both scaffolds was complete, as their water retentions kept constant at similar values, which further validated the relationship between crosslinking and swelling.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of water retained after 10, 30, 45, and 60 min of cross-linking of the coaxial fibers. ‘*’: comparing vs. the PCL/PEG-NB 5k.

3.3. The scaffolds are mechanically strong and viscoelastic materials

Results from tensile tests performed in the hydrated condition on coaxial fiber scaffolds polymerized with a high UV dose are shown in Table 3 and Fig. S3, with representative stress-strain curves in Fig. 3A. The hydrated scaffolds polymerized with a low UV dose were weaker and easily slipping off the clips due to extremely high water contents, resulting in highly variable results (not shown here). The curve for PCL fiber scaffold is also shown for comparison. Tensile test results demonstrate that the coaxial fiber scaffolds are highly elastic and tough. When compared to PCL/PEG-NB 10k scaffolds, PCL/PEG-NB 5k scaffolds exhibit higher Young’s modulus and fracture strength as well as lower strain at fracture. This can be attributed to the difference in the molecular size and bond formation. As PEG-NB 5k solution contains up to twice as many reactive norbornene arms as PEG-NB 10k, PEG-NB 5k can be more reactive than PEG-NB 10k, resulting in a more crosslinked structure with higher stiffness and strength. Also, PEG-NB 10k molecules are longer than PEG-NB 5k, likely creating more spaces in the hydrogel network for water softening. Therefore, the mechanical behaviors of PCL/PEG-NB 5k vs. 10k scaffolds in the wet condition agree with the water retention results. Additionally, the stiffness of PCL fibers is ~8–11 times higher, while the strain at fracture is ~4–6 times lower. The absence of thiol-ene hydrogel sheath leads to stiff, brittle behaviors of PCL fibers.

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of high UV dose cross-linked coaxial blends measured with uniaxial tensile testing.

| Tensile properties | PCL | PCL/PEG-NB 5k | PCL/PEG-NB 10k |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum stress [kPa] | 1466.3 ± 230.5 | 419.6 ± 63.9 (*) | 265.6 ± 41.5 (* #) |

| Maximum strain [%] | 44.7 ± 8.3 | 176.5 ± 7.6 (*) | 255.6 ± 34 (* #) |

| Young’s modulus [kPa] | 3529.5 ± 69.1 | 428.1 ± 86.2 (*) | 310.1 ± 30.2 (*) |

comparing vs. PCL fibers

comparing vs. PCL/PEG-NB 5k.

The statistical significance levels were set at p < 0.05 (* or #).

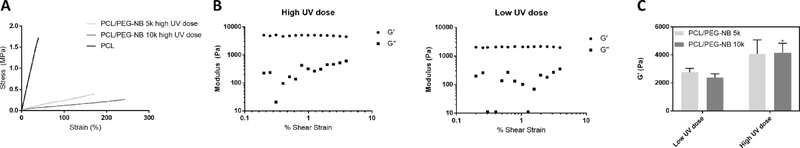

Fig. 3.

Tensile and viscoelastic properties of PCL/PEG-NB coaxially-structured fibrous scaffolds polymerized with different UV doses. (A) Representative stress-strain curves of coaxial PCL/PEG-NB fiber scaffolds polymerized with high UV dose, which are compared with the PCL fiber scaffold. (B) Representative strain sweep results of G’ and G”, from the rheometer measurements of PCL/PEG-NB 10k. (C) Storage modulus, G’, of coaxial fiber scaffolds with PEG-NB 5k or 10k. ‘*’: comparing vs. low UV dose.

Because of the hydrogel nature of coaxial fiber scaffolds, their viscoelastic behaviors were examined with rheometry using strain sweep (Fig. 3B and Fig. S4). The elastic behaviors were dominant in all cross-linked scaffolds, with the storage modulus (G’) greater than the loss modulus (G”). The effects of UV dose and molecular weight of PEG-NB sheath were respectively studied (Fig. 3C), using the G’ values in the linear region (shear strain = 1%) for comparisons. For both PCL/PEG-NB 5k and 10k, a low UV dose resulted in a lower G’, about half of high UV dose scaffolds. Higher dose yielded increased crosslinking among coaxial fibers and reduced water retention in the scaffolds, thus leading to stronger materials. Consistent with fiber and scaffold swelling behaviors, the difference in the storage modulus between PCL/PEG-NB 5k and 10k was not significant. However, limitations in this elasticity measurement must be acknowledged. Herein, coaxial fibers form a discontinuous hydrogel-like network, instead of a continuous material (i.e. composite) that can be properly evaluated using rheometry. This may explain some discrepancies between tensile modulus and storage modulus. Also, when G’, which shows the in-phase response of a material to the applied strain, is highly relative to G” illustrating the out-of-phase response, G” is difficult to detect. This is especially true when the strain is relatively low, as done here. The noisy signals in the G” values illustrate such difficulty with G” detection approaching the transducer limit of the instrument.

Overall, the coaxial fiber scaffolds are mechanically strong and viscoelastic, comparable to soft tissues such as arteries. The tensile properties of PCL/PEG-NB scaffolds match well with those of natural arteries reported in the literature, including arteries’ modulus (~200–400 kPa), strength (~150–1400 kPa), and maximum elongation (~45%–175%).20–23 Also, the stress-strain curves of coaxial fibers present a more linear behavior as opposed to hyperelastic materials, probably due to the interfibrous crosslinks formed during polymerization, which effectively hinder a widespread alignment of the fibers before fracture occurs. The PCL core plays an essential role in stabilizing and strengthening these hydrogel scaffolds, which otherwise would collapse with extremely low modulus under wet conditions. The polymerization process makes scaffolds mechanically stronger due to not only interfibrillar cross-links, but also the intrafibrillar interactions mostly in the sheath. PCL/PEG-NB 5k fibers likely present tighter and higher number of intra- and inter- fibrillar crosslinks than PCL/PEG-NB 10k.

3.4. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy analysis of coaxial PCL/PEG-NB fibers

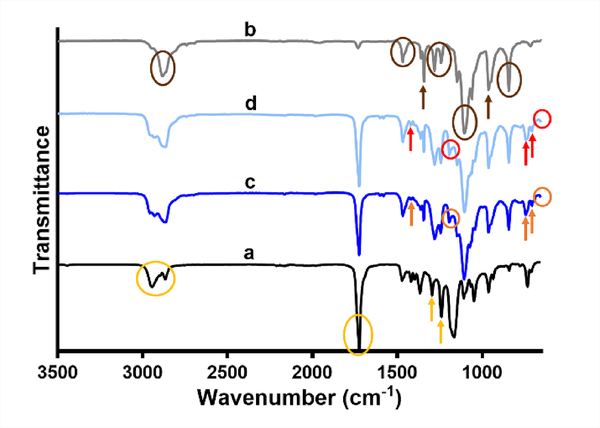

The ATR-FTIR spectra of individual polymers and their coaxial PCL/PEG-NB fibers polymerized with low or high UV dose are shown in Fig. 4 (PCL/PEG-NB 10k) and Fig. S5 (PCL/PEG-NB 5k). In the spectrum of PCL fibers (yellow arrows and circles highlighting the main peaks described), the dual peaks at 2940 cm−1 and 2864 cm−1 can be assigned to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching of CH2 group, the tall, sharp peak at 1721 cm−1 assigned to the stretching of carbonyl group, the one at 1294 cm−1 to C-O and C-C stretching, and the one at 1240 cm−1 to asymmetric C-O-C stretching.24 In the PEG-NB 10k spectrum (brown arrows and circles highlighting the main peaks described), the peak at 2882 cm−1 can be assigned to C-H stretching, the one at 1467 cm−1 to the bending of CH2 group, the one at 1360 cm−1 to CH2 wagging, the dual peaks at 1280 cm−1 and 1241 cm−1 to the twisting vibration of CH2 group, the tall peak at 1096 cm−1 to C-O-C stretching, the one at 960 cm−1 to CH2 rocking, and the peak at 842 cm−1 to C-O-C bending.25 The two spectra of individual polymers correspond well to those of the PCL/PEG-NB 10k coaxial fibers polymerized with high or low UV dose (orange and red arrows and circles highlighting the main peaks described). In addition to the peaks shown in individual polymers, we also found the peaks that characterize the norbornene ring or the thiol-ene bond, including the peak at 1191 cm−1 assigned to the linear chains of 4-arm PEG-NB, a small peak at 1418 cm−1 to the cyclicity of alkanes, one at 743 cm−1 to the norbornene ring, one at 707 cm−1 to out-of-plane bending of the CH group, and one at 653 cm−1 to C-S stretching in the thiol-ene bond.26 Interestingly, the two well-defined peaks at 1280 cm−1 and 1241 cm−1 in the PEG-NB spectrum appear to be merged into one single peak in the coaxial fiber spectra. Also, the intensity of some peaks such as the one at 963 cm−1, is slightly reduced in more polymerized coaxial fibers, further confirming the formation of thiol-ene bond at the expense of breaking double bond in cis-alkene. Some PEG-NB chemical groups have relatively small numbers, and thus may be hidden by other peaks. As ATR-FTIR measures only the reflectance from a film surface, the degree of interaction between the core and sheath polymers was not clearly discerned.

Fig. 4.

ATR-FTIR spectra of individual polymer fibers and their coaxially spun fibers. (a) PCL, (b) PEG-NB 10k, and (c-d) coaxial fibers of PCL/PEG-NB 10k, polymerized with high (c) or low (d) UV dose. The assigned peaks are circled or pointed with arrows.

3.5. Thermal analysis of the coaxial fibers, showing core-sheath interaction

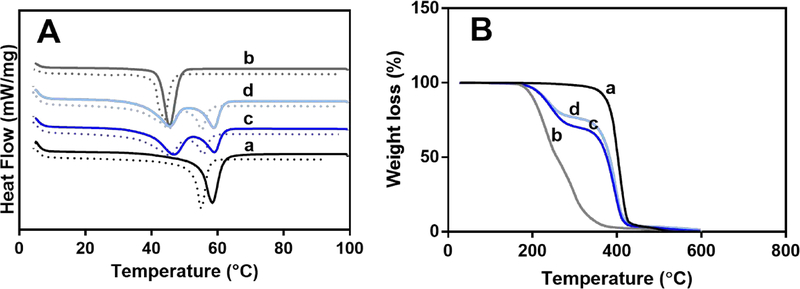

Fig. 5A shows DSC measurements of individual polymers and their coaxial PCL/PEG-NB fibers. First (solid lines) and second (dashed lines) heating curves are both presented. Melting of PCL and PEG-NB 10k occurs at around 60 °C and 45 °C, respectively, during the endothermic processes in both heating curves.27 The second peak, shifting to lower temperatures with respect to the first, is more reliable as it allows the evaluation of the inherent material properties.28 The first peak can be influenced by the thermal history, production, impurities and crystallinity of polymer. The DSC curves of the coaxial fibers show two clear peaks, which correspond to the individual polymers but appear to be smaller than those counterparts, due to their lower weight percent. Additionally, the endothermic peaks for PCL in the coaxial fibers are less intense in the more polymerized coaxial fibers (Fig. 5A and Fig. S6A). This may be because (a) more cross-linked sheath better retains the heat in the polymeric core leading to a faster PCL core degradation, and (b) UV exposure may influence PCL degradation.29 Notably, the glass transition temperature of PCL is −60°C, below the minimum temperature covered by the cooling cycle range.

Fig. 5.

Thermogravimetric analysis results. DSC (A), and TGA (B) measurements of individual polymer fibers and their coaxially spun fibers: (a) PCL, (b) PEG-NB 10k, and (c-d) coaxial fibers of PCL/PEG-NB 10k, polymerized with high (c) or low (d) UV dose.

Fig. 5B shows TGA analyses of individual polymers and their coaxial PCL/PEG-NB fibers. It is found that both PCL and PEG-NB 10k show only one weight-loss step, while the coaxial PCL/PEG-NB fibers polymerized with both UV doses show two well-defined steps. For individual polymers, PCL fibers start to degrade at ~350 °C, showing an abrupt decrease in weight, while PEG-NB start to degrade at ~200 °C with a slower decrease in weight. The two-step, weight-loss TGA curves for the coaxial PCL/PEG-NB fibers correspond to those of PCL and PEG-NB, showing a similar pattern with a main difference in the second step related to PCL degradation. PCL degrades at a lower temperature in PCL/PEG-NB 10k coaxial fibers, compared to that in PCL fibers. This could be due to mechanical pressure and heat transfer from the sheath (PEG-NB 10k) to the core (PCL) leading to a faster core degradation. High surface-volume ratio of core and sheath further promotes the heat transfer.29 Additionally, the degradation of the PCL core occurs faster in the network that has been polymerized for longer time. This could be due to the higher degree of cross-linking which does not allow the energy or heat to dissipate as much, leading to a faster melting of the fiber’s core.30 Finally, the fact that the two steps that correspond to the blend’s single components are not merged but very well-defined in the TGA spectra indicates that there is no chemical reaction between them.29 As all peaks in the TGA and DSC data correspond well to the constituting components of the coaxial fibers, thermal analysis results suggest that the core-sheath interactions might be limited to probably mechanical interlocking and physical entanglement. Fig. S6 shows results from DSC (A) and TGA (B) measurements of PCL/PEG-NB 5k, which follow similar trends.

3.6. In vitro cell biocompatibility of coaxial fiber scaffolds

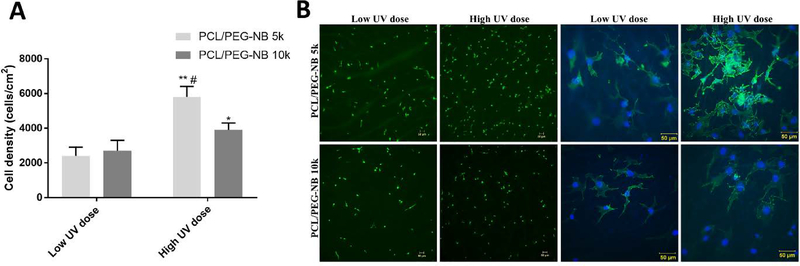

To evaluate cell compatibility of the coaxial fiber scaffolds, vascular endothelial cells were seeded on the four PCL/PEG thiol-ene scaffolds conjugated with RGD peptide: PCL/PEG-NB 5k and PCL/PEG-NB 10k, polymerized with low or high UV dose. Because of the multi-arm structure in PEG-NB, there is always an excess of the “ene” groups on PEG-NB available to react with varied CRGDS concentrations. We previously characterized and reported the direct correlation between the peptide concentration and the peptide density in a crosslinked PEG-NB matrix.31 Results show significant differences in the cell attachment (Fig. 6A). The highest cell attachment was found in the PCL/PEG-NB 5k scaffolds polymerized at a high UV dose, while the lowest was in the PCL/PEG-NB 10k scaffolds polymerized at a low UV dose. Fluorescent imaging of F-actin cytoskeleton and cell nuclei was performed (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Cell biocompatibility of the coaxial fibers. (A) Cell density measured on coaxial PCL/PEG-NB fiber scaffolds. ‘*’ comparing vs. low UV dose, ‘#’ comparing vs. PCL/PEG-NB 10k with high UV dose. (B) In vitro evaluation of hEC attachment on the four coaxial fiber scaffolds. Fluorescent microscopy images show F-actin (green) and DAPI (blue) stains in hECs cultured for 24h on the scaffolds composed of PCL/PEG-NB 5k, and PCL/PEG-NB 10k. Results demonstrate cell attachment with two magnifications (A-D taken at 10X, and E-H taken at 40X). Scale bars = 50 μm.

Cell attachment results demonstrate the influences of both UV dose and PEG-NB molecular weight on the cell behaviors. Overall, a scaffold with higher stiffness and lower water retention, as demonstrated in more crosslinked coaxial fibers and/or smaller PEG-NB molecular weight, led to an increase in cell attachment. More cell attachment on more polymerized coaxial fibers might be due to the stiffness increase in the PEG-NB scaffold. Similarly, PCL/PEG-NB 5k seemed to induce more cell attachment than PCL/PEG-NB 10k, which was likely due to its higher stiffness (Table 3). This is in good agreement with previous studies, in which cells displayed more organized cytoskeleton and stronger attachment through bonds between the cell integrin and matrix ligand on stiffer matrices compared to softer ones, though significant cell-to-cell variability exists.29,32 Also, it has been shown previously that cells migrate from soft to stiff regions of the matrix, where they are more proliferative with more spreading.32

3.7. In vivo evaluation showing unprecedented cell penetration and ECM formation in coaxial fiber scaffolds

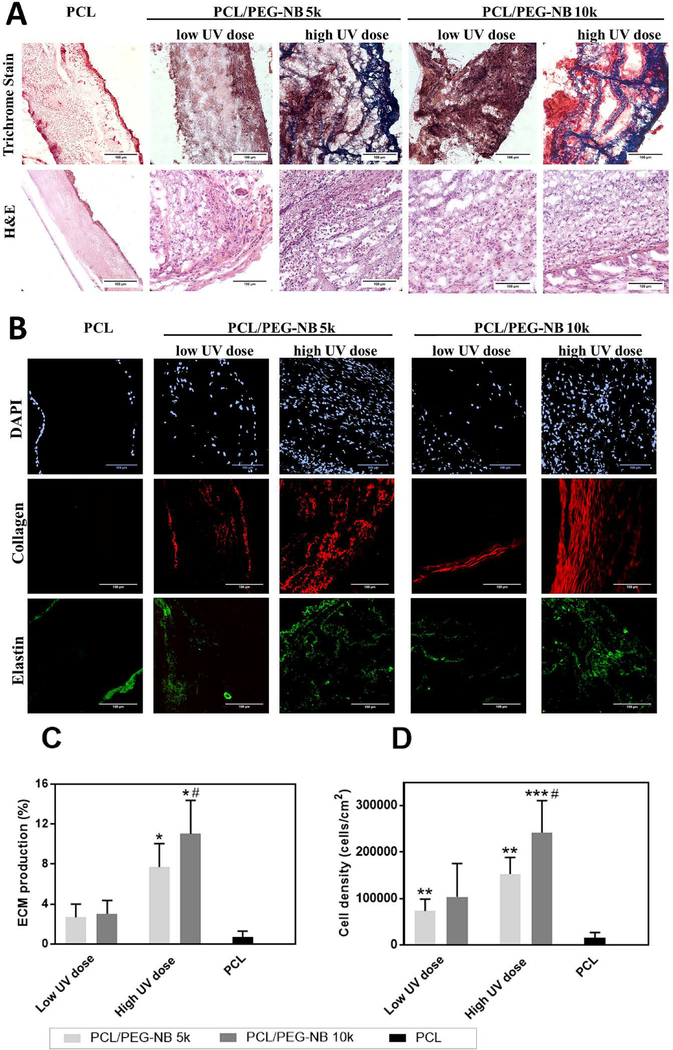

To evaluate cell-material interaction, soft tissue healing and regeneration in the developed coaxial scaffolds in vivo, the scaffolds were implanted subcutaneously into rats for one week and the explants were analyzed by H&E and Masson’s trichrome assays. H&E staining results show that a larger number of cells penetrated deep into the coaxial scaffolds, while only a thin cell layer coated the PCL matrix within 7 days after implantation (Fig. 7A). Further, trichrome staining results show more collagen-rich fibrotic tissue (Fig. 7A) in the stiffer coaxial fiber scaffolds with respect to softer ones, which might be due to more cell penetration in stiffer scaffolds for ECM protein synthesis. To confirm this, DAPI staining was used to visualize cell nuclei (Fig. 7B). For PCL fiber scaffolds, only a monolayer of cells was found on either side of the scaffolds, while all coaxial fiber scaffolds permitted uniform, deep material penetration of cells, with stiffer scaffolds attracting more cells. This result agrees well with our in vitro cell study results.

Fig. 7.

Biocompatibility of the explanted scaffolds. (A) Histological analysis results, showing infiltrated cells and deposited ECM in the explanted scaffolds. Masson’s trichrome stain shows collagen and mucus in blue, nuclei in black, and cytoplasm, keratin, muscle, and intercellular fiber in red. Collagen deposition is observed in the high UV dose coaxial scaffolds. H&E stain shows a large number of cells recruited in the coaxial material compared to PCL fibers, as well as in the high UV dose coaxial scaffolds compared to the low UV dose scaffolds and PCL fibers. (B) Two-photon imaging of the explanted scaffolds. Images show the infiltrated cells (DAPI stain of cell nuclei), as well as the newly-synthesized collagen (red, from SHG imaging) and elastin (green, from TPE imaging). High UV dose coaxial scaffolds show a large number of infiltrated cells as well as an increased deposition of collagen and elastin compared to the other scaffolds. (C) The ECM production and (D) cell density in the explanted scaffolds. High UV dose increased both cell density and ECM production in the coaxial fiber scaffolds compared to PCL fibers. ‘*’ comparing vs PCL, ‘#’ comparing vs. PCL/PEG-NB 10k with low UV dose. (A-B): scale bar = 100 μm.

To further assess the ECM production and determine the relationship between cell infiltration and ECM deposition, two-photon microscopy imaging was employed to visualize collagen and elastin content. Regarding the collagen production (Fig. 7B, using SHG mode), stiffer coaxial fiber scaffolds showed higher collagen content, which was consistent with trichrome staining results. Similar finding was shown in the elastin deposition (Fig. 7B, using TPEF mode). No or little depositions of collagen and elastin were found in PCL fiber scaffolds. To affirm the conclusion, the cell density and ECM production were quantitatively analyzed (Fig. 7C–D). The ECM productions were determined using the area percent of collagen and elastin in the tissue. The results demonstrate that higher ECM production in stiffer coaxial scaffolds was likely caused by more cell infiltration. The in vivo result agrees with our in vitro cell study results, except for a small discrepancy in the cell density. A possible mechanism underlying this might lie in the phenotypic difference in participating cells. Endothelial cells were used in vitro, while different types of cells, including endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts, might be involved in tissue remodeling in vivo. Each cell type has its own preference to the matrix environment in terms of cell proliferation and matrix production, which might lead to slightly different outcomes in vivo. Nevertheless, the difference in the cell density and matrix production in vivo between PCL/PEG-NB 10k and PCL/PEG-NB 5k scaffolds at high UV dose is statistically insignificant. Our results thus suggest that the role of polymer molecular weight (5k vs 10k) in the in vivo cell attachment was not as important as the UV dose. High matrix stiffness at high UV dose could be sufficient to promote extensive cell attachment in vivo, regardless of the polymer molecular weight.

Overall, PCL/PEG-NB coaxial fiber scaffolds show nice integration with surrounding tissues in vivo, presenting improved cell penetration, ECM production, tissue healing and regeneration with respect to PCL fiber scaffolds. In addition, more polymerized coaxial scaffolds show an even more pronounced increase in these reparative/regenerative characteristics. This could occur due to a more organized cytoskeleton, enhanced attachment and migration of ECM-producing cells such as myofibroblasts on relatively stiffer substrates compared to softer matrices.29,32 Herein, the properties of both PCL and PEG-NB are exploited to achieve excellent mechanical property and bioactivity.

To determine materials-induced inflammation, immunofluorescent staining with CD68 to detect the macrophage presence was used with DAPI counterstain (Fig. S7). Results show the absence of macrophages in the coaxial materials, while their presence is observed in the PCL fibers scaffold. The results suggest that PCL fiber material appear to be more reactive producing more inflammation than coaxial materials when implanted in the body. Cells infiltrated in the coaxial material are most likely ECM-producing cells based on the detection of fibrillar collagen and elastin in the materials.

Though we stressed on the material stiffness on in vivo results, an alternative mechanism underlying cell-scaffold interactions in vivo may be related to the steric shielding effect of PEG. Less polymerized PEGNB-sheathed scaffolds retain more water, likely exhibiting elevated steric shielding. Thus, higher water retention in these scaffolds could prevent non-specific absorption of ECM proteins, which potentially benefit vascular regeneration, by inhibiting platelet adhesion, thrombosis or protein-induced fibrosis. Therefore, future investigations should be performed to further assess the combined effects of steric shielding and matrix stiffness of PEGNB-sheathed scaffolds on the vascular regeneration in vivo.

4. Conclusion

Herein, we report the development of porous hydrogels consisting of nanostructured PCL/ PEG thiol-ene coaxial microfibers, and the demonstration of their potential in tissue regeneration. The hybrid fibers contain a hydrophobic core to provide mechanical strength and a photo-clickable, multi-arm PEG thiol-ene sheath to offer tunable stiffness and local physico-chemical properties including hydration and peptide ligand. The novel coaxial fiber scaffolds showed high cell infiltration, ECM production and tissue regeneration in vivo. Further, polymerizing the scaffolds with higher UV dose significantly strengthened and stiffened the scaffolds, which reduced the swelling ratio of the overall scaffolds, but enhanced the cell attachment in vitro as well as cell infiltration and ECM production in vivo. The molecular weight of sheath polymer provides an additional mechanism to alter the fiber structures and properties. This versatile fibrous hydrogel system might be precisely tuned to address the needs of a wide range of soft tissue regenerations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Transmission electron microscopy was done with the technical assistance of staff at the EM Services Core Facility in the Department of MCD Biology, the University of Colorado – Boulder. The work was financially supported by (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute R01HL119371 to W. Tan).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

References

- [1].Kennedy KM, Bhaw-Luximon A, Jhurry D, Acta Biomaterialia, 2017, 50, 41–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Curry AS, Pensa NW, Barlow AM, Bellis SL, Matrix Biology, 2016, 52, 397–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Olvera D, Sathy BN, Carroll SF, Kelly DJ, Acta Biomaterialia, 2017, 64, 148–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Thayer PS, Verbridge SS, Dahlgren LA, Kakar S, Guelcher SA, Goldstein AS, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 2016, 104(8), 1894–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhao W, Ju YM, Christ G, Atala A, Yoo JJ, Lee SJ, Biomaterials, 2013, 34(33), 8235–8240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jiang T, Carbone EJ, Lo KWH, Laurencin CT, Progress in polymer Science, 2015, 46, DOI: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2014.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ding Y, Li W, Zhang F, Liu Z, Zanjanizadeh Ezazi N, Liu D, Santos HA, Advanced Functional Materials, 2019, 29(2), 1802852. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nagiah N, Johnson R, Anderson R, Elliott W, Tan W, Langmuir, 2015, 31, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wu J, Hong Y, Bioactive materials, 2016, 1, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kang Y, Wang C, Qiao Y, Gu J, Zhang H, Peijs T, Kong J, Zhang G, Shi X, Biomacromolecules, 2019, 20(4), 1765–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Madhavan K, Elliott WH, Bonani W, Monnet E, Tan W, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials, 2013, 101, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Elahi MF, Lu W, Guoping G, Khan F, J Bioeng Biomed Sci, 2013, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Johnson R, Ding Y, Nagiah N, Monnet E, Tan W, Materials Science and Engineering: C, 2019, 97, DOI: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tang D, Chen S, Hou D, Gao J, Jiang L, Shi J, Liang Q, Kong D, Wang S, Materials Science and Engineering: C, 2017, 84, DOI: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bonani W, Motta A, Migliaresi C, Tan W, Langmuir, 2012, 28, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Golecki HM, Yuan H, Glavin C, Potter B, Badrossamay MR, Goss JA, Phillips MD, Parker KK, Langmuir, 2014, 30(44), 13369–13374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hamrang A, Howell BA, Foundations of high performance polymers: properties, performance and applications, Apple Academic Press, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liu C, Sun J, Shao M, Yang B, RSC Advances, 2015, 5, 119. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Li Y, Ceylan M, Shrestha B, Wang H, Lu QR, Asmatulu R, Yao L, Biomacromolecules, 2013, 15, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Claes E, Atienza JM, Guinea GV, Rojo FJ, Bernal JM, Revuelta JM, Elices M, 2010. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Buenos Aires, Argentina, August-September, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Khamdaeng T, Luo J, Vappou J, Terdtoon P, Konofagou EE, Ultrasonics EE, 2012, 52, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sommer G, Benedikt C, Niestrawska JA, Hohenberger G, Viertler C, Regitnig P, Cohnert TU, Holzapfel GA, Acta Biomaterialia, 2018, 75, 235–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Vatankhah E, Prabhakaran MP, Semnani D, Razavi S, Morshed M, Ramakrishna S, Biopolymers, 2014, 101, 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Polini A, Pisignano D, Parodi M, Quarto R, Scaglione S, S. PloS one, 2011, 6, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tonda-Turo C, Ruini F, Ramella M, Boccafoschi F, Gentile P, Gioffredi E, D’Urso Labate GF, Ciardelli G, Carbohydrate polymers, 2017, 162, DOI: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cramer NB, Bowman CN, Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry, 2001, 39, 19. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Speranza V, Sorrentino A, De Santis F, Pantani R, The Scientific World Journal, 2014, DOI: 10.1155/2014/720157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mohomed K, Bohnsack DA, American Laboratory, 2013, 45, 3. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Boodagh P, Guo DJ, Nagiah N, Tan W, Journal of Biomaterials science, Polymer edition, 2016, 27, 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yeh CC, Chen CN, Li YT, Chang CW, Cheng MY, Chang HI, Cellular Polymers, 2011, 30, 5. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sharma S, Floren M, Ding Y, Stenmark KR, Tan W, Bryant SJ, Biomaterials, 2017, 143, 17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ladoux B, Mège RM, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2017, 18(12), 743–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.