Abstract

Cocaine abuse remains a pervasive public health problem, and treatments thus far have proven ineffective for long-term abstinence maintenance. Intensive research on the neurobiology underlying drug abuse has led to the consideration of many candidate transmitter systems to target for intervention. Among these, the hypocretin/orexin (hcrt/ox) neuropeptide system holds largely untapped yet clinically viable therapeutic potential. Hcrt/ox originates from the hypothalamus and projects widely across the mammalian central nervous system to produce neuroexcitatory actions via two excitatory G-protein coupled receptor subtypes. Functionally, hcrt/ox promotes arousal/wakefulness and facilitates energy homeostasis. In the early 2000s, hcrt/ox transmission was shown to underlie mating behavior in male rats suggesting a novel role in reward-seeking. Soon thereafter, hcrt/ox neurons were shown to respond to drug-associated stimuli, and hcrt/ox transmission was found to facilitate motivated responding for intravenous cocaine. Notably, blocking hcrt/ox transmission using systemic or site-directed pharmacological antagonists markedly reduced motivated drug-taking as well as drug-seeking in tests of relapse. This review will unfold the current state of knowledge implicating hcrt/ox receptor transmission in the context of cocaine abuse and provide detailed background on animal models and underlying midbrain circuits. Specifically, attention will be paid to the mesoaccumbens, tegmental, habenular, pallidal and preoptic circuits. The review will conclude with discussion of recent preclinical studies assessing utility of suvorexant - the first and only FDA-approved hcrt/ox receptor antagonist - against cocaine-associated behaviors.

Keywords: Addiction, cocaine, dopamine, hypocretin/orexin, midbrain, psychostimulant(s), reward, ventral tegmental area

Introduction.

Use of psychostimulants such as cocaine and amphetamine can lead to dependence and deteriorate the wellbeing of addicted individuals, their friends and families as well as entire communities. Cocaine abuse can lead to adverse effects ranging from skin irritation/infection to sympathomimetic toxicity, paranoia/hallucinatory delirium, and sudden cardiac death. Subjectively, cocaine produces transient euphorigenic (positive) effects followed by effects of the opposite valence (negative) - craving, dysphoria, anxiety, and irritability (e.g., Breiter et al. 1997). These negative effects during withdrawal are thought to propagate drug use in effort to relieve the negative emotional state and comprise the “dark side of addiction” (Koob 2013). To date, no pharmacotherapies are approved to manage cocaine use disorder, and thus novel transmitter systems are being explored in effort to reduce incidence and severity of cocaine abuse.

This review will focus on hypothalamic hypocretin/orexin (hcrt/ox) as one such set of targets by detailing its connectivity and functions (known and suspected) in the context of cocaine (and related psychostimulant) abuse. Indeed, circulating hcrt/ox levels were significantly elevated in humans with a history of methamphetamine abuse (Chen et al. 2016), and hcrt/ox-based pharmacotherapies are being explored in a clinical study for the management of cocaine abuse (NCT02785406 on https://clinicaltrials.gov/). The review will begin with a discussion of measures used when modeling psychostimulant abuse in animal subjects. Next, the characterization and physiological roles of hcrt/ox will be detailed. Thereafter, midbrain circuits that govern reward-seeking and the encoding of aversive events - both of which are known to propagate cocaine abuse - will be provided as will discussion of how hcrt/ox influences these circuits. Specifically, attention will be given to mesoaccumbens, tegmental, habenular, pallidal and preoptic circuits. Finally, the therapeutic potential of targeting hcrt/ox transmission to manage psychostimulant abuse, including studies with the clinically-available hcrt/ox receptor antagonist suvorexant (Belsomra®), will conclude the review.

1). Modeling cocaine abuse in animals: a methodological review.

The ability to test novel agents as potential therapies to manage cocaine abuse relies on our ability to model clinically-relevant features of the disease under controlled laboratory conditions. The following subsections will review behavioral paradigms and measures used to characterize abuse potential of psychostimulants in animals including (i) place conditioning, (ii) intravenous drug self-administration, (iii) intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS), and (iv) recording ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs). Novel medications suspected to produce therapeutically-favorable effects are tested within these behavioral paradigms.

1.1). Assessments of reward and reinforcement.

During place conditioning, animals learn to associate unique contextual stimuli with appetitive or aversive outcomes as interpreted from approach-avoid behaviors. Utilized for place conditioning is a shuttle-box apparatus composed of two contextually-distinguished compartments (Contexts) where visual, tactile, and olfactory cues form two unique environments. Test subjects undergo a series of conditioning trials during which experimental and control treatments become associated with each of two Contexts. Following conditioning, test subjects freely shuttle between two Contexts, and time on each Context is measured. Initial studies revealed that cocaine and amphetamine produce place preference which aligns with the subjectively rewarding effects reported by users immediately following administration (Mucha et al. 1982; Spyraki et al. 1982a, b). Interestingly, while pairing a context with intravenous cocaine immediately post-infusion creates a conditioned place preference, incorporating a 15-min delay during conditioning trials between the cocaine infusion and placement in context leads to the development of conditioned place aversion (Ettenberg et al. 1999). Similarly in humans, a cocaine infusion is associated with euphorigenic effects that wane and are followed by craving, dysphoria and negative affect (e.g., Breiter et al. 1997). Place conditioning enables researchers to evaluate rewarding and aversive effects of psychostimulants learned through associative memories.

In 1962, James Weeks announced his “experimental addiction” model whereby unrestrained rats could perform a behavior (lever pressing; herein termed operant response) for intravenous morphine (Weeks 1962). Intravenous drug self-administration remains to-date a model with face and construct validity that measures abuse potential and captures the volitional aspect of drug-taking. Nearly all drugs that are abused by humans including cocaine and amphetamine are self-administered by laboratory animals (Thompson and Schuster 1964; Dougherty and Pickens 1973). Notably, response-outcome contingencies can be altered to probe unique aspects of behavior. For example, a subject’s motivational drive can be assessed by measuring the number of operant responses performed to retrieve drug injection that are progressively increased following each self-injection - this measure is referred to as the breakpoint (Richardson and Roberts 1996). Session length can be adjusted to model clinically-relevant binge-like drug consumption. Importantly, extending session length allows test subjects to escalate drug intake across sessions (Ahmed and Koob 1998). Adapted in 2011 was the use of a behavioral economic analysis of cocaine’s reinforcing properties involving fixed-ratio access to self-administered cocaine using an incrementally descending series of dose (per injection) across the session (Oleson et al. 2011). By constructing demand curves, researchers can assess the hedonic value (interpreted by metric Q0) and motivation (interpreted by metric α) associated with cocaine self-administration within a single session. Additionally being studied at this time was the use of intermittent access reinforcement schedules which are designed to produce peaks and troughs in drug level as are experienced during episodic binges in addicted individuals (Zimmer et al. 2011, 2012). Finally, the subject’s drug-taking environment as well as discrete cues can become predictive of drug access, and experimenters can model the extent to which contexts and cues reinvigorate drug-seeking in tests of relapse following extinction of the learned operant response. In these tests, triggers including stress and drug-priming can be used which are thought to produce behavioral disinhibition. Collectively, drug self-administration is a customizable model allowing researchers to probe how pharmacological and behavioral interventions alter drug-taking and -seeking under controlled laboratory conditions.

1.2). Assessments of mood/affective changes.

Early studies designed to probe brain reward function in laboratory animals involved delivery of electrical currents through steel wires to sites in the brain contingent on operant responses from the implanted animal; this assay is termed intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) and was introduced in the 1950s (Olds and Milner 1954). Typically, the intensity of current needed to support self-stimulation is used as a metric to determine shifts in reward function, but the rate of responding at a fixed current can also be used. Numerous sites (structures and fiber tracts) in the rodent central nervous system support self-stimulation including hypothalamus, preoptic area and medial forebrain bundle (Corbett and Wise 1980). Euphorigenic agents including cocaine and amphetamine invariably prime reward function in ICSS tests (Goodall and Carey 1975; Koob et al. 1975; Esposito et al. 1978) which is interpreted to correspond to immediate positive subjective effects associated with psychostimulant use in humans. Conversely, deficits in reward function are thought to reflect an anhedonic (dysphoric) state that corresponds in part to negative mood/depressed states in humans although no such self-report from animal subjects exists to confirm this relationship. Brain sites associated with stress responsivity including the amygdala become engaged during cocaine withdrawal and are suspected to underlie the negative affective behavioral phenotype (Goussakov et al. 2006; for review, D’Souza and Markou 2010). Accordingly, withdrawal from cocaine is characterized by deficient reward function as evidenced by elevated self-stimulation thresholds (Schaefer and Michael 1983; Kokkinidis and McCarter 1990). These studies highlight ICSS as a behavioral assay that probes reward-processing brain structures in a manner sensitive to environmental and pharmacological treatments including experience with psychostimulants.

A natural measure used by researchers to evaluate subjective responsivity to stimuli/treatments in rats includes recording their ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs). Like other mammals, rats vocalize to convey information. Vocalizations within the human auditory range (0- to 14-kHz) are emitted by rats in situations where predatory or conspecific contact is occurring or imminent (Litvin et al 2007). Rat vocalizations also include those within ultrasonic frequency ranges (>14-kHz) that can be detected using bat detectors or condenser microphones. USVs around 22-kHz emitted from adult rats can be relatively long in duration (up to 3.5 s), are often monotonic following brief pitch fluctuation upon emission onset, and are linked to experimental conditions associated with affective distress or alarm including aggression, social isolation, and electrical footshock (Berg and Baenninger 1973; Tonoue et al. 1986; Blanchard et al. 1991; Brudzynski et al. 1991, 1993). USVs with a mean frequency around 50-kHz are typically shorter in length (15–100 ms), acoustically varied by way of pitch modulations (jumps/sweeps; a contiguous emission characterized by rapid sinusoidal-like fluctuations between 40- and 90-kHz is termed trill) and are elicited upon experimental conditions associated with receipt of appetitive stimuli including “tickling” as well as during mating (McIntosh et al. 1984; Panksepp and Burgdorf 2000). The recent two decades have enriched our understanding of how psychostimulants affect USVs (for reviews, see Barker et al. 2015, Simmons et al. 2018a). Systemic cocaine and amphetamine elicit high rates of 50-kHz USVs which are sensitive to incubation/sensitization and crudely align with changes in locomotor activity (Ahrens et al. 2009; Mu et al. 2009). Later studies confirmed high rates of 50-kHz USVs during cocaine self-administration notably during the anticipation time-epoch as well as following initial cocaine infusions (Barker et al. 2010, 2014; Browning et al. 2011; Maier et al. 2012; Avvisati et al. 2016; Simmons et al. 2018b). Conversely, earlier reports revealed a strong presence of 22-kHz USVs when rats were withdrawn from oral or intravenous cocaine (Barros and Miczek 1996; Mutschler and Miczek 1998a, b). Now, USVs can be objectively quantified using automated deep learning software (Coffey et al. 2019). Thus, USVs correspond with subjective states of positive and negative affect based on their emission frequency and can be non-invasively incorporated into behavioral models of psychostimulant addiction.

2). Hypocretin/orexin: discovery, characterization and role in cocaine abuse.

2.1). Discovery, anatomy and physiology.

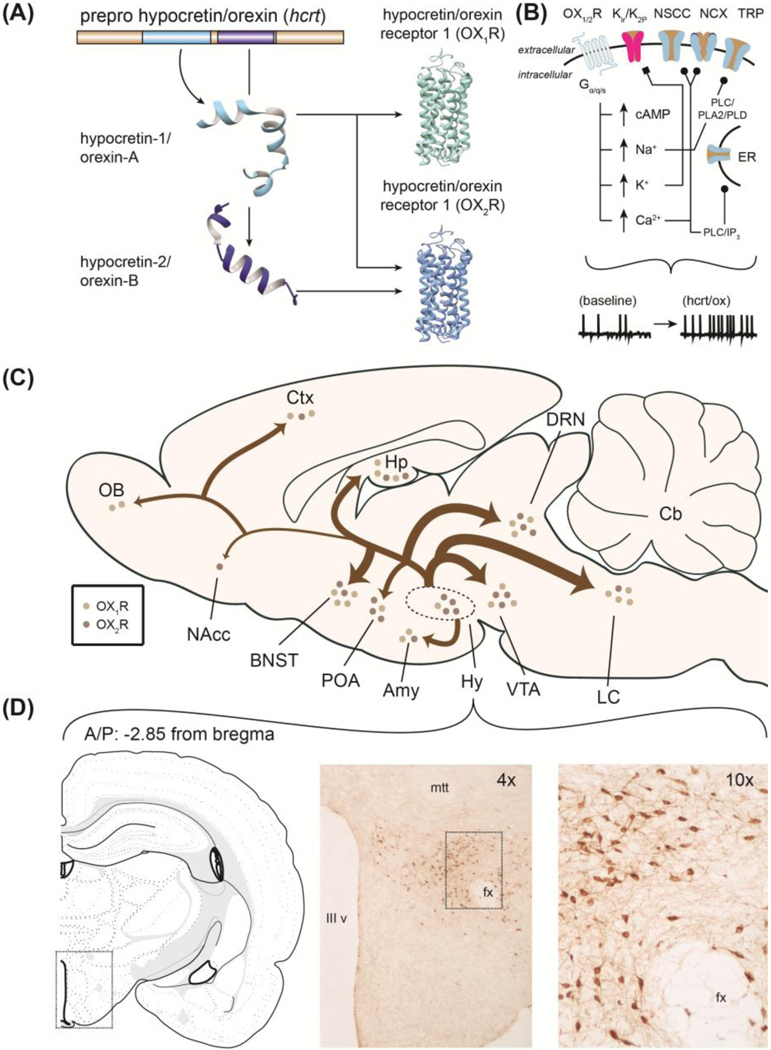

The hypocretin/orexin (hcrt/ox) neuropeptide system was discovered and characterized in the late 1990s by two independent research teams. Gautvik and colleagues (1996) identified 23 novel mRNAs in rat tissues of which one (clone 35; now termed hypocretin [hcrt] for position in hypothalamus and for sequential homology to the gut hormone secretin) was restricted to hypothalamus and possessed proteolytic maturation sites (Gautvik et al. 1996; de Lecea et al. 1998). Application of hcrt peptide enhanced post-synaptic depolarizations in vitro suggesting prominent neuroexcitatory action associated with its transmission. A second team identified the same hypothalamic precursor mRNA, mature peptides and two Gq-linked receptors (OX1R, OX2R) using cell lines transfected with unique orphan GPCR cDNA (Sakurai et al. 1998) (Figure 1A). Central injection of these novel peptides stimulated feeding behavior leading to its naming “orexin” for the Greek word orexis meaning appetite.

Figure 1.

(A) Hcrt/ox mRNA and two mature protein products (hcrt-1/OX-A and hcrt-2/OX-B). (B) Mechanisms through which hcrt/ox exerts neuroexcitatory actions. (C) Origin and projections of hypothalamic orexin neurons with relative quantitative distribution of receptors derived from in situ hybridization study and pathway intensity from fiber innervation using studies immunofluorescence. Amy – amygdala, BNST – bed nucleus of stria terminalis, Cb – cerebellum, Ctx – cortex, DRN – dorsal raphe nucleus, Hp – hippocampus, Hy – hypothalamus, LC – locus coeruleus, NAcc – nucleus accumbens, OB – olfactory bulb, POA – preoptic area, VTA – ventral tegmental area. (D) Immunohistochemical characterization of the orexin field within rat hypothalamus. Atlas image adapted from Brain Maps: Structure of the Rat Brain, Third Edition (Swanson 2004). IIIv – third ventricle, fx – fornix, mtt – mammillothalamic tract. Figure originally contained within and adapted from Gentile et al. 2017a.

Hcrt/ox is connected to brain regions that facilitate motivated action and emotional expression. While the precise innervation of hcrt/ox to neurochemically-defined cellular populations is still being explored, Peyron and colleagues (1998) were the first to profile hcrt/ox cell bodies and fibers across rat brain. Dense hcrt/ox fiber immunoreactivity was observed in locus coeruleus (LC) followed by raphe nuclei, compacta division of substantia nigra (SN), bed nucleus of stria terminalis (BNST), central grey and ventral tegmental area (VTA) (Figure 1C). This anatomical characterization report is widely cited and provided a basis for functions ranging from energy homeostasis (feeding, thermoregulation), regulation of sleep/wakefulness via innervation to LC as well as motivated behaviors via innervation to midbrain. Supporting work by Marcus and colleagues (2001) profiled hcrt/ox receptor (OX1R and OX2R) mRNA across rat brain using X-ray autoradiography. Relatively strong OX1R mRNA signal was found within LC, BNST, midbrain and hypothalamus whereas OX2R mRNA was observed within septal/hippocampal and habenular regions (Figure 1C) (see also Trivedi et al. 1998). In accordance with innervation to wake-promoting brainstem structures, two seminal papers clarified the powerful actions of hcrt/ox on regulating sleep noting the clinical condition narcolepsy as characterized by marked reductions in circulating hcrt/ox (Chemelli et al. 1999; Lin et al. 1999) - wake-promoting actions of hcrt/ox are largely attributed to OX2R-mediated transmission. Collectively, these findings support that hcrt/ox shares reciprocal connectivity with brain regions that facilitate arousal, motivated action as well as those governing emotional responses.

Since original observations by de Lecea and colleagues 1998, neuroexcitatory actions of hcrt/ox have been identified on both GABA- and glutamate-producing cell types through both hcrt/ox receptor subtypes (van den Pol et al. 1998; for review, see Khoo and Brown 2014). Numerous direct and indirect intracellular signaling mechanisms have been proposed as contributors to physiological excitation in neurons which are summarized in Figure 1B (for details, see Kukkonen 2014, 2016). Neuroexcitatory actions of hcrt/ox occur on VTADA cells (Korotkova et al. 2003; Muschamp et al. 2007), noradrenaline (NA) producing neurons of LC (Hagan et al. 1999), and others (Eriksson et al. 2001, Burdakov et al. 2003, Yan et al. 2008). Taken together, hcrt/ox produces excitation by cation transport regulation (enhancing Ca2+ influx, suppressing K+ efflux) and itself is promiscuously regulated by local peptides as well as by canonical neurotransmitters. These studies support that hcrt/ox synaptic inputs and outputs are diversely regulated, and that reciprocal connections are thus far known to exist between hcrt/ox and midbrain structures including VTA indicating likely roles in stimulus processing and motivated behavior.

2.2). Roles of circulating hypocretin/orexin in cocaine abuse.

A timeline depicting major discoveries relating hcrt/ox transmission and psychostimulant abuse is provided in Figure 2 (events written in magenta are of particular interest), and readers are referred to several noteworthy reviews (James et al. 2016; Gentile et al. 2017a). The first studies to examine hcrt/ox in the specific context of psychostimulant abuse were published in 2005 (Boutrel et al. 2005; Harris et al. 2005). In work by Boutrel and colleagues (2005), the authors observed that central injection of hcrt-1 (1.5 nmol) robustly invigorates responding on a cocaine-paired lever during tests of reinstatement. Further, systemic blockade of OX1Rs (30 mg/kg, SB-334867) attenuated footshock-stimulated (stress-induced) cocaine-seeking. Interestingly, it was observed that central hcrt-1 injection (1.5 nmol) significantly elevates reward thresholds - dampens reward function - in intracranially self-stimulating rats up to 12-h post-injection. Harris and colleagues (2005) found that exposure to a cocaine-paired chamber elevates Fos-immunoreactivity within hcrt/ox cells. A related study reported significant enhancement of Fos-immunoreactivity within hcrt/ox cells - notably within the dorsomedial hypothalalmus - when rats were subjected to a context-elicited reinstatement probe test according to an A-B-A design (Hamlin et al. 2008). Together, results from these studies provided the basis that hcrt/ox transmission participates in maladaptive behaviors associated with cocaine abuse and influences hedonic state/affect.

Figure 2.

Timeline depicting notable discoveries relating hcrt/ox transmission in the context of pscyhostimulant abuse. Studies in magenta text are of particular interest to the topic of this review. (a) Gautvik et al. 1996, (b) de Lecea et al. 1998, (c) Sakurai et al. 1998, (d) van den Pol et al. 1998, (e) Peyron et al. 1998, (f) Chemelli et al. 1999, (g) Lin et al. 1999, (h) Smart 2000, (i) Marcus et al. 2001, (j) Estabrooke et al. 2001, (k) Fadel and Deutch 2002, (l) Korotkova et al. 2003, (m) Gulia et al. 2003, (n) Harris et al. 2005, (o) Boutrel et al. 2005, (p) Narita et al. 2006, (q) Borgland et al. 2006, (r) Muschamp et al. 2007, (s) Wang et al. 2009, (t) Whitman et al. 2009, (u) Borgland et al. 2009, (v) Hollander et al. 2012, (w) Yang 2014, (x) NCT02785406, (y) Gentile et al. 2018, (z) Steiner et al. 2018.

A role for hcrt/ox transmission in the motivational properties to self-administer cocaine - and other palatable reinforcers - has also been made clear. Borgland and colleagues (2009) observed that systemic OX1R blockade with SB-334867 (10 mg/kg) significantly reduced breakpoints for intravenous cocaine as well as high-fat chocolate pellets under progressive-ratio (PR) access conditions but failed to affect operant responding for normal food chow (see also Hollander et al. 2012). Importantly, other work revealed no effect of SB-334867 (30 mg/kg) on responding for intravenous cocaine under a fixed-ratio 1 (FR-1) schedule of reinforcement (Smith et al. 2009) suggesting a selective role of OX1Rs in the motivational aspect of drug-taking. In effort to disentangle contribution of hcrt/ox receptor subtypes, Prince and colleagues (2015) observed decreased motivated cocaine-taking when rats were pretreated with OX1R (30 mg/kg, SB-334867) or dual OX1/2R (100 mg/kg, almorexant) antagonists whereas no effects were seen when OX2Rs were selectively blocked using 4PT. Recently, James and colleagues (2018a) demonstrated that rats subjected to 14 d of intermittent access to cocaine produces greatest consumption of cocaine and greatest motivational drive compared to rats having access to short- long-access self-administration sessions. Importantly, this work revealed that intermittent cocaine access produces other behavioral features associated with chronic cocaine use including depression-like behavior and anhedonia. Rats subjected to intermittent cocaine access showed persistent elevations in Fosimmunoreactive neurons containing hcrt/ox, and pharmacological blockade of OX1Rs was effective in reducing demand elasticity for self-administered cocaine. Other work by this group using a large cohort of rats reveals an association between motivated responding for intravenous cocaine (measured using demand elasticity [α] as discussed in Section 1.1) and efficacy of systemic OX1R blockade (James et al. 2018b; see also James et al. 2016). This body of work using behavioral pharmacological tools reveals that hcrt/ox transmission, specifically via OX1Rs, is critical for driving motivated responses directed at obtaining highly palatable food rewards and drugs of abuse.

Using genetic targeting, Steiner and colleagues (2018) tested how genetic hcrt/ox deficiency in mice (hcrt−/−) affects cocaine-evoked behaviors. The team observed blunted ambulation from male hcrt−/− mice following initial systemic cocaine injection and delayed, but not abolished, behavioral sensitization. Whereas all genotypes displayed initial place preference for a cocaine-paired context following the final conditioning trial, only wildtype and heterozygous comparator mice showed persistent place preference when tested again 2 weeks later (i.e., after “passive extinction”). Under FR-1 access conditions, cocaine self-administering hcrt−/− mice consumed significantly less cocaine relative to wildtype control mice at the highest dose tested (1.5 mg/kg/inf). Finally, while wildtype mice showed characteristic enhancements of cue-driven cocaine-seeking in reinstatement tests proceeding 2–3 weeks into abstinence, hcrt−/− mice failed to show this “incubation of craving” effect. This work corroborates with a prior study capturing significantly lower self-administered cocaine intake in hcrt-r1−/− mice (Hollander et al. 2012). Other recent work observes decreased cocaine self-administration during 6- but not 1-h sessions in rats receiving bilateral shRNA-mediated knockdown of hcrt (Schmeichel et al. 2018). Genetically downregulating hcrt/ox peptide production or the OX1R receptor subtype blunts behavioral indices of maladaptive reward-seeking.

Blockade of hcrt/ox transmission has been repeatedly shown to suppress indices of drug relapse. Smith and colleagues (2009) observed appreciable reductions in cued cocaine-seeking after pre-treatment with the selective OX1R antagonist SB-334867 (30 mg/kg). Readers should note that, at effective pre-treatment doses could additionally be found reductions in inactive lever presses, such that high doses of OX1R antagonists could contribute to general depression of ambulation/activity of tested subjects. Systemic blockade of OX1Rs (10 mg/kg, SB-334867) can suppress context-elicited cocaine-seeking after operant responding is extinguished or after periods of forced abstinence (Smith et al. 2010). Separate work reveals that systemic OX1R blockade using SB-334867 (30 mg/kg) significantly reduces operant responses for playback of a cocaine-paired conditioned stimulus (Hutcheson et al. 2011). These studies demonstrate that OX1R-mediated transmission critically contributes to cocaine-seeking invigorated from exposure to cocaine-paired cues and contexts. Taken as a whole, a case for targeting OX1Rs selectively compared to OX2Rs alone or OX1/2R targeting to reduce severity of cocaine abuse - and other reward-related pathological conditions - is evident (see Khoo and Brown 2014). To our knowledge, OX1R-selective antagonists have suffered from undesirable properties for clinical use yet their development, we argue, will be of paramount therapeutic benefit.

3). Midbrain circuits and reward-seeking: roles of hypocretin/orexin.

The converging lines of work discussed above support that hcrt/ox transmission supports motivated behaviors for high-value reinforcers including cocaine. The following sub-sections will detail several specific pathways through which hcrt/ox is shown to influence motivated behavior (summarized in Figure 3) including the (i) mesoaccumbens pathway, (ii) habenular/tegmental pathways, (iii) ventral pallidal pathways, and (iv) preoptic pathways.

Figure 3.

Circuit schematic of neurochemically-defined midbrain pathways participating in the facilitation (reward) of constraint (aversion) of motivated behaviors. *indicates pathways of hypothesized but untested function. Hyp – hypothalamus, LHb – lateral habenula, NAcc – nucleus accumbens, POA – preoptic area, RMTg – rostromedial tegmentum, VP – ventral pallidum, VTA – ventral tegmental area.

3.1). Dopamine and the mesoaccumbens pathway.

A principal target of VTADA is the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), and this mesoaccumbens pathway is critical for processing positively- and negatively-valenced events. The VTA and the medial forebrain bundle (MFB) - which encompasses forebrain-projecting DA fibers - are sites that readily support electrical self-stimulation indicating roles in reward processing and positive reinforcement. Electrical stimulation of VTA and MFB elevate extracellular NAcc DA and enhance firing rates of NAcc cells in vivo (Wolske et al. 1993; Young and Michael 1993). Drugs of abuse including cocaine elevate NAcc DA levels in part through pre-synaptic inhibition of the DA transporter (DAT) (Baird and Lewis 1964; Ross and Renyi 1967; Di Chiara and Imperato 1988; Pettit and Justice Jr. 1989). In vivo, VTADA neurons exhibit phasic (burst) activity relative to baseline (tonic) firing upon reward receipt including to intravenous cocaine as well as to reward-predictive cues (Mirenowicz and Schultz 1996; Ghitza et al. 2003; Owesson-White et al. 2008). Curiously, VTADA neurons within the ventral VTA phasically respond to aversive events such as footshock although the targets of this cellular population is not known (Brischoux et al. 2009). The VTA receives diverse inputs (Yetnikoff et al. 2015) of which hypothalamic hcrt/ox has received considerable attention.

Tract tracing work reveals ~20% of hcrt/ox cells target VTA, and that hcrt/ox terminals closely appose VTADA cells (Fadel and Deutch 2002). Relatively high density of OX1R and OX2R mRNA is detected in VTA compared to NAcc (Marcus et al. 2001). Physiological function of hcrt/ox in VTA was studied by Borgland and colleagues (2006) showing that hcrt/ox potentiates VTADA synaptic strength via OX1Rs. Curiously, electron microscopy analysis suggests that the majority of hcrt/ox fibers within VTA pass to more caudal structures or signal within VTA non-synaptically, although a small proportion were seen synaptically-linked to VTADA and VTAGABA neurons (Balcita-Pedicino and Sesack 2007). Even if synapsing onto a minority of VTA cells, OX1R blockade significantly suppresses firing of VTADA neurons during the active/wake phase in animals (Moorman and Aston-Jones 2010) and has robust effects on regulating reward-driven, motivated behaviors. In the context of psychostimulant abuse, Borgland and colleagues (2006) observed that locomotor sensitization to repeated cocaine injections is dependent in part on OX1Rs in VTA as local injection with an OX1R antagonist blocked its development. Relatedly, rats with a history of intravenous cocaine self-administration show augmented NMDA-mediated excitatory post-synaptic currents on VTADA neurons following bath-applied hcrt/ox peptide whereas no such effects were observed in tissue from naïve rats (Borgland et al. 2009). Behaviorally, intra-VTA OX1R blockade (10 nmol) suppresses motivation to self-administer intravenous cocaine (España et al. 2010), and modulation of OX1Rs in VTA diminishes cocaine-evoked DA dynamics in NAcc (for review, see Brodnik et al. 2018). Relatedly, bilateral intra-VTA hcrt/ox peptide injection enhances motivated responding for intravenous cocaine (España et al. 2011). Indeed, intra-VTA OX1R additionally reduces cued reinstatement of cocaine-seeking (James et al. 2011). Relatively fewer studies have observed functional roles of hcrt/ox directly within NAcc - recent reports suggests that hcrt/ox transmission in NAcc facilitates stress-elicited reinstatement of morphine-seeking (Farzinpour et al. 2019). Other roles include averting risky decisions (Blomeley et al. 2018) and promoting arousal (Luo et al. 2018). Thus, hcrt/ox transmission via OX1Rs in VTA supports motivated reward-seeking and may contribute to the rewarding effects of self-administered psychostimulants. In support of this notion, Muschamp and colleagues (2014) reports that intra-VTA OX1R blockade (3.2 ng) produces elevations in reward thresholds (anhedonia) suggesting constraint on brain reward function.

3.2). Habenular/tegmental circuits.

Newer tools have uncovered functional roles of neurochemically-defined cellular populations in lateral habenula (LHb) and rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg) in the context of reward-seeking and processing aversive stimuli. A sub-population of VTADA→LHb cells from anterior VTA encode reward as determined by real-time place preference when photostimulated (Stamatakis et al. 2013). Interestingly, stimulation of VTADA→LHb terminals suppresses activity of recorded cells in the caudal division (tail) of VTA - now termed RMTg - which the LHb is known to richly innervate (Jhou et al. 2009). Earlier, Stamatakis and Stuber (2012) observed that LHbGlu→RMTg stimulation produces real-time place aversion, complimenting an anti-reward function of excitatory LHb cells as shown in non-human primates (Matsumoto and Hikosaka 2007). Stimulating LHbGlu→RMTg additionally disrupts operant responding for sucrose rewards suggesting a suppressive role in positive reinforcement. From these studies, a general consensus is that VTADA→LHb suppresses glutamatergic output from LHb to targets including caudal VTA (RMTg). Interestingly, diverse inhibitory inputs to VTADA were captured in work by Polter and colleagues (2018) leading to the suggestion that RMTg may co-transmit glycine (in addition to GABA) to VTADA. Additional experiments revealed that VTAGABA →LHb stimulation produces rewarding and reinforcing effects (Lammel et al. 2015) yet VTAGlu→LHb stimulation produces opposite, aversive behavioral responses (Root et al. 2014b). In the context of psychostimulant abuse, intravenous cocaine transiently inhibits LHb cell activity in vivo, and a proportion of these cells spike in activity during the post-injection time epoch when cocaine is known to be aversive (Jhou et al. 2013). Indeed, the majority of activated LHb cells (i.e., during the aversive post-cocaine time epoch) were found to target the RMTg. It was suggested then that the LHb→RMTg pathway may be bidirectionally sensitive to opponent affective states associated with psychostimulants (Rothwell and Lammel 2013). Habenular and tegmental pathways are the focus of many research teams determined to disentangle functional roles of neurochemically- and pathway-defined cellular populations within these structures (for review, see Morales and Margolis 2017) including influence from potential neuropeptide modulators such as hcrt/ox.

Anatomically, LHb shows moderate labeling for hcrt/ox fibers and relatively high OX2R mRNA (Peyron et al. 1998, Marcus et al. 2001). In agreement with early anatomical work, a novel LHbGABA sub-population was recently identified and found to be sensitive to hcrt/ox transmission via OX2Rs as well as DA with suspected although largely untested roles in motivation and behavioral response to alarm (Zhang et al. 2018). Other work shows a reciprocal LHb→Hyphcrt/ox projection that regulates sleep integrity and responsivity to anesthetic agents (Gelegen et al. 2018). Interestingly, photostimulation of HypGlu→LHb negatively regulates palatable food consumption (Stamatakis et al. 2016) suggesting an anti-reward/anhedonic function. In this study, glutamate-producing cells are targeted using a VGluT2-cre mouse line, and it is known that ~50% of hcrt/ox cells contain VGluT2 mRNA (Rosin et al. 2003) such that the observed behavioral effects may in part be regulated by hcrt/ox transmission. Anatomical studies mapping hcrt/ox connectivity to-date have not differentiated between adjacent tegmental structures (VTA and RMTg), yet unpublished observations support that hcrt/ox provides comparable afferent input to VTA and RMTg (Simmons, unpublished observations). Functionally, it is hypothesized that hcrt/ox in RMTg would constrain reward function in part by quieting mesoaccumbens DA transmission.

3.3). Ventral pallidal circuits.

The ventral palldium (VP) is a neurochemically hetereogenous structure receiving dense innervation from the anteriorally-positioned NAcc (for review, see Root et al. 2015). Pertaining to psychostimulant abuse, Root and colleagues (2013) noted firing rate increases from a sub-population of dorsolateral VP (dlVP) cells in vivo during approach and response epochs associated with cocaine self-administration in rats (see also Root et al. 2010). Interestingly, in vivo recordings suggest that VP neurons respond more quickly and consistently to reward delivery compared to NAcc neurons (Ottenheimer et al. 2018). Other work shows that chronic cocaine injections dynamically alter synaptic strength at NAcc→VP synapses (Creed et al. 2016; see also James and Aston-Jones 2016). Furthermore, normalizing cocaine-elicited changes in NAcc→VP synaptic strength weakened behavioral responses associated with repeated cocaine injections including locomotor sensitization. A separate report shows that photostimulation of NAcc cells significantly reduces VP cell activity (evaluated by Fos mapping) supporting a negative regulatory role in reward-seeking possibly through preferential inhibition of VPGABA cells (Wang et al. 2014). In the context of drug relapse, chemogenetically silencing the VP→VTA pathway - specifically from cells within the rostral VP - significantly reduces cued cocaine-seeking in rats (Mahler et al. 2014) consistent with earlier work demonstrating a key role of NAcc→dlVP pathway in cued cocaine-seeking (Stefanik et al. 2013). More recently, a role for VPGlu cells in producing aversive responses has been ascribed in part via a LHb→RMTg relay (Tooley et al. 2018, see also Wulff et al. 2018). Stimulation to VPGlu produced place aversion and concurrently enhanced a population of LHb and RMTg cells in vivo while ablation of VPGlu was shown to diminish conditioned taste aversion. These results corroborate with a report by Faget and colleagues (2018) who observe that pathway-sensitive photostimulation of VPGlu→LHb produces place aversion while VPGABA→VTA drives preference thus conferring opponent rewarding/aversive actions of heterogenous VP populations. Collectively, VP comprises a neurochemically heterogenous cellular population that bidirectionally influences reward-driven, motivated behaviors largely through connections with NAcc, VTA and RMTg.

The VP shows moderate labeling for hcrt/ox fibers as well as cells containing OX1R mRNA (Baldo et al. 2003, Ch’ng and Lawrence 2015). Functionally, hcrt/ox within the caudal VP has been shown to enhance subjective “liking” for experimenter-administered sucrose (Ho and Berridge 2013; see also Castro et al. 2015) suggesting an important role in hedonic reactivity to foods and possibly other reinforcers and extending prior work showing caudal VP sensitivity to mu opioid receptor stimulation (Smith and Berridge 2005). Corroborating unpublished work from this team reveal that photostimulation of projections from lateral hypothalamus to caudal VP additionally enhances hedonic reactivity to sucrose without affecting “disgust” reactions assessed by intraoral quinine infusions (Castro et al. 2015). Beyond this important work, roles of hcrt/ox in VP are still to be uncovered. It reasons though that hcrt/ox transmission within caudal VP would support motivated responding for drug reinforcers such as self-administered cocaine. Additional work needs to uncover which cellular population within caudal VP hcrt/ox is connected to - as its transmission is associated with enhancing reward-associated hedonic reactivity, it is possible that hcrt/ox preferentially activates the VPGABA sub-population.

3.4). Preoptic circuits.

The preoptic area (POA) lies between VP and Hyp and is predominantly comprised of medial (mPOA), lateral (lPOA), and hypothalamic-median (mnPOA) divisions. A multitude of functions has been associated with mammalian POA functioning including (i) mating behavior and parental care for mPOA neurons (Hull and Dominguez 2007, Bosch and Neumann 2012), (ii) thirst regulation within mnPOA (Abbott et al. 2016, Allen et al. 2018), and (iii) sleep, locomotor regulation, and reward/aversion encoding within lPOA (Barker et al. 2017, Luppi et al. 2017, Subramanian et al. 2018; but see McHenry et al. 2017). On this latter function, Barker and colleagues (2017) showed that LPOGABA projects to LHb to promote reward whereas LPOGlu→LHb promotes aversion. Relatedly, a population of steroid-sensitive neurotensin-producing mPOA neurons targeting VTA (mPOA→VTA) - shown to support social signal encoding such as to male odors - were shown to encode reward and support optical self-stimulation in female mice (McHenry et al. 2017). To our knowledge, the mPOA has not been shown to be critically involved in the processing of aversive events, whereas the lPOA is comprised of neurochemically distinct sub-populations that support behavioral responses associated with both reward and aversion. While the POA transmits neuropeptides to target structures, several non-resident neuropeptides such as hcrt/ox regulate its net activation.

Anatomical work shows the POA as receiving dense, uniform fiber innervation from hcrt/ox with slightly greater abundance of hcrt/ox receptor mRNA within medial compared to lateral compartments (Peyron et al. 1998, Marcus et al. 2001, Chou et al. 2002). Reciprocally, POAGABA and POAGlu cells - notably originating from the laterally-positioned magnocellular POA - appose Hyphcrt/ox somata (Agostinelli et al. 2017). España and colleagues (2001) are credited as providing the first function of hcrt/ox within mPOA noting wake-promoting actions following local peptide delivery. Similarly, the lPOA (specifically the ventrolateral POA [vlPOA]) is a hcrt/ox-sensitive site - local peptide delivery obstructed sleep quality (promoted arousal) and increased energy expenditure compared to vehicle-pretreated control subjects (Mavanji et al. 2015) supporting prior work in lPOA (Methippara et al. 2000). mnPOA is suspected to negatively regulate hcrt/ox cellular activity as pharmacological inactivation of mnPOA significantly increased Fos expression within hcrt/ox cells, although readers should note that this work was performed in anesthetized rats (Kumar et al. 2008). Important new work reveals monosynaptic connectivity between POAGABA and hypothalamic hcrt/ox (Saito et al. 2013, 2018). Other functions of hcrt/ox within POA include regulation of appetite (Sarihi et al. 2015), maternal care (Rivas et al. 2016), and male sexual behavior (Gulia et al. 2003). This latter work (Gulia et al. 2003) is among the first studies to support a role of central hcrt/ox transmission in the regulation of reward-driven, motivated behaviors. No studies to-date have examined the role of hcrt/ox innervation in POA on motivated behaviors for drugs of abuse. It is hypothesized however that hcrt/ox supports motivated reward-seeking primarily through connections to the lPOAGABA sub-population.

4). Suvorexant (MK-4305) as a potential therapeutic to manage psychostimulant abuse.

With the apparent involvement of hcrt/ox transmission in regulating arousal and wakefulness, numerous companies invested in producing hcrt/ox-based medications for managing sleep disorders. While earlier compounds suffered from undesirable pharmacokinetics, toxicity profiles, and/or complications associated with clinical trials, Merck Research Laboratories synthesized and tested a hcrt/ox receptor antagonist that eventually became the first-in-class medication approved by the Food and Drug Administration indicated for managing primary insomnia—a disorder characterized by chronic sleep deficiencies (Whitman et al. 2009; Cox et al. 2010). Suvorexant (MK-4305) possesses a 7-methyldiazepane core, chlorobenzoxazole for improved lipophilicity for brain penetrability and boasts favorable potencies against OX1R (Ki = 0.55 nM) and OX2R (Ki = 0.35 nM) with clean ancillary profile against 170 screened off-target enzymes, receptors and ion channels (Cox et al. 2010). Suvorexant produced significant enhancement in delta and REM sleep epochs with appreciable reductions in light sleep (no movement, predominantly consisting of theta waves, moderate electromyogram activity) from telemetry-implanted rats. In a multi-center trial of 522 patients diagnosed with primary insomnia, Michelson and colleagues (2014) reported significant improvement in subjective total sleep time and time to sleep onset in suvorexant-treated patients compared to the placebo-treated control population (NCT01021813 from https://ClinicalTrials.gov).

Our team provided the first preclinical evidence that suvorexant produces therapeutically-favorable effects on behaviors associated with cocaine abuse. Gentile and colleagues (2018) (Figure 4A) revealed that systemic suvorexant (30 mg/kg, IP) reduces the number of cocaine infusions (~0.36 mg/kg/inf) earned under high-effort access conditions compared to prior-day baseline performance. While we cannot altogether discount possible behavioral suppression/somnolence at effective doses of suvorexant, we failed to observe any effect of suvorexant on cocaine-stimulated locomotor activity tested in a separate group of rats. We additionally tested how suvorexant affects the development of place preference for a context paired with systemic cocaine and observed modest but non-significant reduction of time in the cocaine-paired context indicating a relatively weak role in passive reward learning. Finally, in an anesthetized mouse preparation, suvorexant was found to significantly blunt cocaine-elicited elevations in NAcc DA which may correspond to reward-attenuating effects observed during cocaine self-administration.

Figure 4.

Effects of suvorexant on (A.i) motivated cocaine-taking and (A.ii) cocaine-evoked DA response in ventral striatum. All panels of (A) are adapted from Gentile et al. 2018. Additionally, we observe that suvorexant decreases cocaine-elicited impulsivity when injected systemically (B.i) as well as when deposited bilaterally into the VTA (B.ii). All panels of (B) are adapted from Gentile et al. 2017b.

Recent work examining the role of hcrt/ox transmission in the context of cocaine-associated impulsive choice was recently published (Gentile et al. 2017b) (Figure 4B). Impulsivity is defined as a tendency to engage in behaviors without forethought and is found in many psychiatric states while simultaneously leading to poorer outcomes in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder, and psychostimulant use disorders (e.g., Evenden 1999; de Wit 2009). Contained within, we demonstrate that systemic suvorexant produces a dose-dependent decrease in premature responses in the 5-choice serial reaction time task (5-CSRTT) which can be interpreted as improving attentional capacity. Notably, we found that pre-treatment with high-dose suvorexant (30 mg/kg) significantly suppressed premature responding in subjects following acute cocaine injection suggesting a protective effect against cocaine-elicited impulsivity. Finally, the experiment was repeated in a separate cohort of subjects with bilateral cannulae directed above VTA. In this group, pre-treatment with suvorexant (3 μg/hemisphere) was again able to attenuate cocaine-elicited premature responding. Throughout the above-mentioned experiments, we found no indication that suvorexant produced general task disruption/locomotor impairment. This study supports that suvorexant may improve attentional capacity in drug-naive and in cocaine-experienced subjects.

We additionally tested the efficacy of systemic suvorexant against reward and reinforcement associated with self-administration of the cathinone-derived synthetic psychostimulant 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) in rats (Simmons et al. 2017). Consistent with prior work demonstrating a selective role for hcrt/ox receptor antagonist against the motivational drive associated with cocaine self-administration, suvorexant did not affect the number of MDPV infusions earned under FR-1 access conditions. Interestingly, we did find that suvorexant pre-treatment (10 mg/kg) blunted the rate of positively-valenced 50-kHz USVs occurring during anticipation (i.e., pre-lever) as well as post-lever time epochs. We additionally observed trending positive correlations between effects of suvorexant on MDPV infusions and anticipatory 50-kHz USVs. These analyses align with the notion that 50-kHz USVs possess predictive utility against measures of psychostimulant reward (e.g., place preference) (e.g., Ahrens et al. 2013). Collectively, we have shown suvorexant to be effective in reducing maladaptive behaviors associated with cocaine use including impulsivity and motivated drug-taking. However, all of our studies to-date have utilized acute pre-treatments (either systemic or intracranial) and, in order to appreciate potential clinical applicability, studies utilizing repeated treatments with suvorexant against addiction-related behaviors are warranted.

5). Concluding remarks and future directions.

In this review, we first described tests and metrics used to understand reward and reinforcement in animal subjects. We focused on how cocaine influences behavior in these tests and on how hcrt/ox transmission can be targeted to normalize cocaine-associated behaviors. A growing body of work pursued since the mid-2000s provides support that suppressing hcrt/ox transmission (notably via OX1Rs) decreases pathological motivation. In fact, in July 2018, Foltin and Evans (2018) demonstrated reward-attenuating effects of OX1R blockade in female monkeys trained to self-administer cocaine. We additionally detail our recent work using the clinically-available hcrt/ox antagonist suvorexant in animal models of psychostimulant addiction. Importantly, we describe what is known regarding the anatomical innervation and function of hcrt/ox within specific midbrain and basal forebrain circuits (mesoaccumbens, tegmental, habenular, pallidal, preoptic) that regulate the encoding of rewarding and aversive events. Unpublished work includes examining effects of suvorexant on brain reward function using ICSS, and using site-directed suvorexant to elucidate functional contribution of specific structures such as VTA and RMTg to reinforcement associated with cocaine self-administration. Our discussion at present lacks direct clinical translation, but we refer readers to track progress of an ongoing trial (NCT02785406) which will test the efficacy of suvorexant on craving and affective state of cocaine users.

Several notable points obfuscate a clear understanding of the dynamics through which hcrt/ox transmits to target structures. To start, hcrt/ox-producing cells rarely, if ever, transmit just hcrt/ox. mRNA for the vesicular glutamate transporter type-2 (VGluT2) are detected in ~50% of hcrt/ox-immunolabeled cells of rat brain (Rosin et al. 2003). Curiously, hcrt/ox cells produce mRNA for the peptide dynorphin, the endogenous ligand of kappa opioid receptors (KORs) (Chou et al. 2001). In an ex vivo preparation, dynorphin suppressed activity of hcrt/ox-producing cells by altering spike frequency and calcium currents; opposingly, bath application of a KOR antagonist augmented hcrt/ox activity supporting the interpretation that hypothalamic-based dynorphin exerts suppressive tone over the hcrt/ox-producing cell population (Li and van den Pol 2006). Williams and Behn (2011) modeled the dynamic interplay between hcrt/ox and dynorphin based on experimental slice physiology data and concluded that desensitization of hcrt/ox-producing cells to KOR stimulation permits a rapid shift of these cells from KOR-mediated inhibition to hcrt/ox-driven excitation—in turn, hcrt/ox release is stimulated and physiological activation is signaled to targets. Indeed, Muschamp and colleagues (2014) found that unique populations of VTADA cells exhibit preferential sensitivity to excitatory actions of hcrt/ox, inhibitory actions of dynorphin, or mixed sensitivity. Follow-up retrograde tracing work revealed preferential excitatory actions of VTADA→NAcc whereas VTADA→amygdala were preferentially inhibited by dynorphin (Baimel et al. 2017). Functionally, KOR activation opposes hcrt/ox-mediated behavioral effects (e.g., sucrose seeking) in brain structures including the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (Matzeu et al. 2018). Studies designed to directly target the hcrt/ox-producing cell population should appreciate the potential contribution of co-transmitters to observed effects.

A second notable point is the technical challenge in producing transgenic rodent lines with selective and persistent expression of cre within hcrt/ox-producing cells, although some newer reports show what appears to be excellent transfection (e.g., Blomeley et al. 2018). Alternative approaches include microinjecting viruses in effort to express transgenes of interest including optical and pharmacogenetic channels under promoters unique to hcrt/ox-producing cells (Grafe et al. 2018). No studies to date have used manipulation strategies against hcrt/ox circuits in experimental models of psychostimulant addiction. Additionally, no studies have so far been able to transfect hcrt/ox-producing cells with calcium indicators for activity readout in behavioral states associated with reward-seeking. Armed with knowledge derived from such ambitious experiments would provide important clarity in defining the contexts when hcrt/ox-based pharmacotherapies would be of greatest clinical utility.

Highlights.

Hypocretin/orexin transmission supports motivation for psychostimulants in animals.

Reward-regulating midbrain circuits are critically influenced by hypocretin/orexin.

Suvorexant is the first (and only) hypocretin/orexin receptor antagonist in clinical use.

Suvorexant normalizes pathological behavior associated with cocaine use in animals.

Acknowledgements.

The authors appreciate helpful discussions with John W. Muschamp, Ellen M. Unterwald, Lynn G. Kirby and Lee-Yuan Liu-Chen. The authors thank Emily Clark (Center for Substance Abuse Research, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University) for assistance with Figure 3. SJS and TAG were supported by a NIDA training grant (T32 DA007237 to Ellen M. Unterwald). SJS was additionally supported by a NINDS training grant (T32 NS007413 to Michael B. Robinson).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

For Special Issue of Brain Research entitled “Orexin receptor antagonists for the treatment of addiction and related psychiatric disease”.

References.

- Agostinelli LJ, Ferrari LL, Mahoney CE, Mochizuki T, Lowell BB, Arrigoni E, & Scammell TE (2017). Descending projections from the basal forebrain to the orexin neurons in mice. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 525(7), 1668–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, & Koob GF (1998). Transition from moderate to excessive drug intake: change in hedonic set point. Science, 282(5387), 298–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens AM, Ma ST, Maier EY, Duvauchelle CL, & Schallert T (2009). Repeated intravenous amphetamine exposure: rapid and persistent sensitization of 50-kHz ultrasonic trill calls in rats. Behavioural brain research, 197(1), 205–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens AM, Nobile CW, Page LE, Maier EY, Duvauchelle CL, & Schallert T (2013). Individual differences in the conditioned and unconditioned rat 50-kHz ultrasonic vocalizations elicited by repeated amphetamine exposure. Psychopharmacology, 229(4), 687–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avvisati R, Contu L, Stendardo E, Michetti C, Montanari C, Scattoni ML, & Badiani A (2016). Ultrasonic vocalization in rats self-administering heroin and cocaine in different settings: evidence of substance-specific interactions between drug and setting. Psychopharmacology, 233(8), 1501–1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baimel C, Lau BK, Qiao M, & Borgland SL (2017). Projection-target-defined effects of orexin and dynorphin on VTA dopamine neurons. Cell reports, 18(6), 1346–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird JRC, & Lewis JJ (1964). The effects of cocaine, amphetamine and some amphetamine-like compounds on the in vivo levels of noradrenaline and dopamine in the rat brain. Biochemical pharmacology, 13(11), 1475–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcita‐ Pedicino JJ, Omelchenko N, Bell R, & Sesack SR (2011). The inhibitory influence of the lateral habenula on midbrain dopamine cells: ultrastructural evidence for indirect mediation via the rostromedial mesopontine tegmental nucleus. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 519(6), 1143–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo BA, Daniel RA, Berridge CW, & Kelley AE (2003). Overlapping distributions of orexin/hypocretin- and dopamine- β- hydroxylase immunoreactive fibers in rat brain regions mediating arousal, motivation, and stress. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 464(2), 220–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Miranda-Barrientos J, Zhang S, Root DH, Wang HL, Liu B, … & Morales M. (2017). Lateral preoptic control of the lateral habenula through convergent glutamate and GABA transmission. Cell reports, 21(7), 1757–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Root DH, Ma S, Jha S, Megehee L, Pawlak AP, & West MO (2010). Dose-dependent differences in short ultrasonic vocalizations emitted by rats during cocaine self-administration. Psychopharmacology, 211(4), 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Simmons SJ, & West MO (2015). Ultrasonic vocalizations as a measure of affect in preclinical models of drug abuse: a review of current findings. Current neuropharmacology, 13(2), 193–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Simmons SJ, Servilio LC, Bercovicz D, Ma S, Root DH, … & West MO. (2014). Ultrasonic vocalizations: evidence for an affective opponent process during cocaine self-administration. Psychopharmacology, 231(5), 909–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros HMT, Miczek KA (1996). Withdrawal from oral cocaine in rats: ultrasonic vocalizations and tactile startle. Psychopharmacology, 125(4), 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrot M, Sesack SR, Georges F, Pistis M, Hong S, & Jhou TC (2012). Braking dopamine systems: a new GABA master structure for mesolimbic and nigrostriatal functions. Journal of Neuroscience, 32(41), 14094–14101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg DS, & Baenninger R (1973). Hissing by laboratory rats during fighting encounters. Behavioral biology, 8(6), 733–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard RJ, Blanchard DC, Agullana R, & Weiss SM (1991). Twenty-two kHz alarm cries to presentation of a predator, by laboratory rats living in visible burrow systems. Physiology & behavior, 50(5), 967–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomeley C, Garau C, & Burdakov D (2018). Accumbal D2 cells orchestrate innate risk-avoidance according to orexin signals. Nature neuroscience, 21(1), 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland SL, Chang SJ, Bowers MS, Thompson JL, Vittoz N, Floresco SB, … & Bonci A. (2009). Orexin A/hypocretin-1 selectively promotes motivation for positive reinforcers. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(36), 11215–11225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland SL, Taha SA, Sarti F, Fields HL, & Bonci A (2006). Orexin A in the VTA is critical for the induction of synaptic plasticity and behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Neuron, 49(4), 589–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch OJ, & Neumann ID (2012). Both oxytocin and vasopressin are mediators of maternal care and aggression in rodents: from central release to sites of action. Hormones and behavior, 61(3), 293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutrel B, Kenny PJ, Specio SE, Martin-Fardon R, Markou A, Koob GF, & de Lecea L (2005). Role for hypocretin in mediating stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(52), 19168–19173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiter HC, Gollub RL, Weisskoff RM, Kennedy DN, Makris N, Berke JD, … & Mathew RT. (1997). Acute effects of cocaine on human brain activity and emotion. Neuron, 19(3), 591–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brischoux F, Chakraborty S, Brierley DI, & Ungless MA (2009). Phasic excitation of dopamine neurons in ventral VTA by noxious stimuli. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 106(12), 4894–4899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodnik ZD, Alonso IP, Xu W, Zhang Y, Kortagere S, & España RA (2018). Hypocretin receptor 1 involvement in cocaine-associated behavior: Therapeutic potential and novel mechanistic insights. Brain research. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning JR, Browning DA, Maxwell AO, Dong Y, Jansen HT, Panksepp J, & Sorg BA (2011). Positive affective vocalizations during cocaine and sucrose self-administration: a model for spontaneous drug desire in rats. Neuropharmacology, 61(1–2), 268–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudzynski SM, Bihari F, Ociepa D, & Fu XW (1993). Analysis of 22 kHz ultrasonic vocalization in laboratory rats: long and short calls. Physiology & behavior, 54(2), 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudzynski SM, Ociepa D, & Bihari F (1991). Comparison between cholinergically and naturally induced ultrasonic vocalization in the rat. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 16(4), 221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdakov D, Liss B, & Ashcroft FM (2003). Orexin excites GABAergic neurons of the arcuate nucleus by activating the sodium—calcium exchanger. Journal of Neuroscience, 23(12), 4951–4957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro DC, Cole SL, & Berridge KC (2015). Lateral hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens, and ventral pallidum roles in eating and hunger: interactions between homeostatic and reward circuitry. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 9, 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch’ng SS, & Lawrence AJ (2015). Distribution of the orexin-1 receptor (OX1R) in the mouse forebrain and rostral brainstem: a characterisation of OX1R-eGFP mice. Journal of chemical neuroanatomy, 66, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemelli RM, Willie JT, Sinton CM, Elmquist JK, Scammell T, Lee C, … & Fitch TE. (1999). Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell, 98(4), 437–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WY, Kao CF, Chen PY, Lin SK, & Huang MC (2016). Orexin-A level elevation in recently abstinent male methamphetamine abusers. Psychiatry research, 239, 9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Lee CE, Lu J, Elmquist JK, Hara J, Willie JT, … & Saper CB. (2001). Orexin (hypocretin) neurons contain dynorphin. Journal of Neuroscience, 21(19), RC168–RC168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Bjorkum AA, Gaus SE, Lu J, Scammell TE, & Saper CB (2002). Afferents to the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus. Journal of Neuroscience, 22(3), 977–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey KR, Marx RG, & Neumaier JF (2019). DeepSqueak: a deep learning-based system for detection and analysis of ultrasonic vocalizations. Neuropsychopharmacology, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett D, & Wise RA (1980). Intracranial self-stimulation in relation to the ascending dopaminergic systems of the midbrain: a moveable electrode mapping study. Brain research, 185(1), 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CD, Breslin MJ, Whitman DB, Schreier JD, McGaughey GB, Bogusky MJ, … & Bruno JG. (2010). Discovery of the dual orexin receptor antagonist [(7 R)-4-(5-chloro-1, 3-benzoxazol-2-yl)-7-methyl-1, 4-diazepan-1-yl][5-methyl-2-(2 H-1, 2, 3-triazol-2-yl) phenyl] methanone (MK-4305) for the treatment of insomnia. Journal of medicinal chemistry, 53(14), 5320–5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed M, Ntamati NR, Chandra R, Lobo MK, & Lüscher C (2016). Convergence of reinforcing and anhedonic cocaine effects in the ventral pallidum. Neuron, 92(1), 214–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza MS, & Markou A (2010). Neural substrates of psychostimulant withdrawal-induced anhedonia. In Behavioral neuroscience of drug addiction (pp. 119–178). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao XB, Foye PE, Danielson PE, … & Frankel WN. (1998). The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95(1), 322–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit H (2009). Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addiction biology, 14(1), 22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, & Imperato A (1988). Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 85(14), 5274–5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty J, & Pickens R (1973). FIXED-INTERVAL SCHEDULES OF INTRAVENOUS COCAINE PRESENTATION IN RATS 1. Journal of the experimental analysis of behavior, 20(1), 111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson KS, Sergeeva O, Brown RE, & Haas HL (2001). Orexin/hypocretin excites the histaminergic neurons of the tuberomammillary nucleus. Journal of Neuroscience, 21(23), 9273–9279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- España RA, Melchior JR, Roberts DC, & Jones SR (2011). Hypocretin 1/orexin A in the ventral tegmental area enhances dopamine responses to cocaine and promotes cocaine self-administration. Psychopharmacology, 214(2), 415–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- España RA, Oleson EB, Locke JL, Brookshire BR, Roberts D, & Jones SR (2010). The hypocretin–orexin system regulates cocaine self-administration via actions on the mesolimbic dopamine system. European Journal of Neuroscience, 31(2), 336–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- España RA, Reis KM, Valentino RJ, & Berridge CW (2005). Organization of hypocretin/orexin efferents to locus coeruleus and basal forebrain arousal-related structures. Journal of comparative neurology, 481(2), 160–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooke IV, McCarthy MT, Ko E, Chou TC, Chemelli RM, Yanagisawa M, … & Scammell TE. (2001). Fos expression in orexin neurons varies with behavioral state. Journal of Neuroscience, 21(5), 1656–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL (1999). Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology, 146(4), 348–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadel J, & Deutch AY (2002). Anatomical substrates of orexin–dopamine interactions: lateral hypothalamic projections to the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience, 111(2), 379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faget L, Zell V, Souter E, McPherson A, Ressler R, Gutierrez-Reed N, … & Hnasko TS. (2018). Opponent control of behavioral reinforcement by inhibitory and excitatory projections from the ventral pallidum. Nature communications, 9(1), 849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzinpour Z, Taslimi Z, Azizbeigi R, Karimi-Haghighi S, & Haghparast A (2019). Involvement of orexinergic receptors in the nucleus accumbens, in the effect of forced swim stress on the reinstatement of morphine seeking behaviors. Behavioural brain research, 356, 279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautvik KM, De Lecea L, Gautvik VT, Danielson PE, Tranque P, Dopazo A, … & Sutcliffe JG. (1996). Overview of the most prevalent hypothalamus-specific mRNAs, as identified by directional tag PCR subtraction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93(16), 8733–8738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelegen C, Miracca G, Ran MZ, Harding EC, Ye Z, Yu X, … & Vyssotski AL. (2018). Excitatory pathways from the lateral habenula enable propofol-induced sedation. Current Biology, 28(4), 580–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile TA, Simmons SJ, Barker DJ, Shaw JK, España RA, & Muschamp JW (2018). Suvorexant, an orexin/hypocretin receptor antagonist, attenuates motivational and hedonic properties of cocaine. Addiction biology, 23(1), 247–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile TA, Simmons SJ, & Muschamp JW (2017a). Hypocretin (Orexin) in Models of Cocaine Addiction. In The Neuroscience of Cocaine (pp. 235–245). [Google Scholar]

- Gentile TA, Simmons SJ, Watson MN, Connelly KL, Brailoiu E, Zhang Y, & Muschamp JW (2017b). Effects of Suvorexant, a Dual Orexin/Hypocretin Receptor Antagonist, on Impulsive Behavior Associated with Cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghitza UE, Fabbricatore AT, Prokopenko V, Pawlak AP, & West MO (2003). Persistent cue-evoked activity of accumbens neurons after prolonged abstinence from self-administered cocaine. Journal of Neuroscience, 23(19), 7239–7245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goussakov I, Chartoff EH, Tsvetkov E, Gerety LP, Meloni EG, Carlezon WA Jr, & Bolshakov VY (2006). LTP in the lateral amygdala during cocaine withdrawal. European Journal of Neuroscience, 23(1), 239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafe LA, Eacret D, Dobkin J, & Bhatnagar S (2018). Reduced Orexin System Function Contributes to Resilience to Repeated Social Stress. eNeuro, ENEURO-0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulia KK, Mallick HN, & Kumar VM (2003). Orexin A (hypocretin-1) application at the medial preoptic area potentiates male sexual behavior in rats. Neuroscience, 116(4), 921–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan JJ, Leslie RA, Patel S, Evans ML, Wattam TA, Holmes S, … & Munton RP. (1999). Orexin A activates locus coeruleus cell firing and increases arousal in the rat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 96(19), 10911–10916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin AS, Clemens KJ, & McNally GP (2008). Renewal of extinguished cocaine-seeking. Neuroscience, 151(3), 659–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Wimmer M, & Aston-Jones G (2005). A role for lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward seeking. Nature, 437(7058), 556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CY, & Berridge KC (2013). An orexin hotspot in ventral pallidum amplifies hedonic ‘liking’for sweetness. Neuropsychopharmacology, 38(9), 1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander J, Pham D, Fowler C, & Kenny PJ (2012). Hypocretin-1 receptors regulate the reinforcing and reward-enhancing effects of cocaine: pharmacological and behavioral genetics evidence. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 6, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull EM, & Dominguez JM (2007). Sexual behavior in male rodents. Hormones and behavior, 52(1), 45–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson DM, Quarta D, Halbout B, Rigal A, Valerio E, & Heidbreder C (2011). Orexin-1 receptor antagonist SB-334867 reduces the acquisition and expression of cocaine-conditioned reinforcement and the expression of amphetamine-conditioned reward. Behavioural pharmacology, 22(2), 173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James MH, Charnley JL, Levi EM, Jones E, Yeoh JW, Smith DW, & Dayas CV (2011). Orexin-1 receptor signalling within the ventral tegmental area, but not the paraventricular thalamus, is critical to regulating cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 14(5), 684–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James MH, Mahler SV, Moorman DE, & Aston-Jones G (2016). A decade of orexin/hypocretin and addiction: where are we now?. In Behavioral Neuroscience of Orexin/Hypocretin (pp. 247–281). Springer, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- James MH, & Aston-Jones G (2016). The ventral pallidum: proposed integrator of positive and negative factors in cocaine abuse. Neuron, 92(1), 5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James MH, Stopper CM, Zimmer BA, Koll NE, Bowrey HE, & Aston-Jones G (2018a). Increased number and activity of a lateral subpopulation of hypothalamic orexin/hypocretin neurons underlies the expression of an addicted state in rats. Biological Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James MH, Bowrey HE, Stopper CM, & Aston-Jones G (2018b). Demand elasticity predicts addiction endophenotypes and the therapeutic efficacy of an orexin/hypocretin-1 receptor antagonist in rats. European Journal of Neuroscience. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhou TC, Geisler S, Marinelli M, Degarmo BA, & Zahm DS (2009). The mesopontine rostromedial tegmental nucleus: a structure targeted by the lateral habenula that projects to the ventral tegmental area of Tsai and substantia nigra compacta. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 513(6), 566–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhou TC, Good CH, Rowley CS, Xu SP, Wang H, Burnham NW, … & Ikemoto S. (2013). Cocaine drives aversive conditioning via delayed activation of dopamine-responsive habenular and midbrain pathways. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(17), 7501–7512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo SY, Brown RM (2014). Orexin/hypocretin based pharmacotherapies for the treatment of addiction: DORA or SORA? CNS Drugs, 28(8), 713–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyashchenko LI, Mileykovskiy BY, Maidment N, Lam HA, Wu MF, John J, … & Siegel JM. (2002). Release of hypocretin (orexin) during waking and sleep states. Journal of Neuroscience, 22(13), 5282–5286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinidis L, & McCarter BD (1990). Postcocaine depression and sensitization of brain-stimulation reward: analysis of reinforcement and performance effects. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 36(3), 463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF (2013). Negative reinforcement in drug addiction: the darkness within. Current opinion in neurobiology, 23(4), 559–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korotkova TM, Sergeeva OA, Eriksson KS, Haas HL, & Brown RE (2003). Excitation of ventral tegmental area dopaminergic and nondopaminergic neurons by orexins/hypocretins. Journal of Neuroscience, 23(1), 7–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen JP (2014). Lipid signaling cascades of orexin/hypocretin receptors. Biochimie, 96, 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen JP (2016). Orexin/hypocretin signaling. In Behavioral Neuroscience of Orexin/Hypocretin (pp. 17–50). Springer, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Szymusiak R, Bashir T, Suntsova N, Rai S, McGinty D, & Alam MN (2008). Inactivation of median preoptic nucleus causes c-Fos expression in hypocretin-and serotonin-containing neurons in anesthetized rat. Brain research, 1234, 66–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammel S, Steinberg EE, Földy C, Wall NR, Beier K, Luo L, & Malenka RC (2015). Diversity of transgenic mouse models for selective targeting of midbrain dopamine neurons. Neuron, 85(2), 429–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, & van den Pol AN (2006). Differential target-dependent actions of coexpressed inhibitory dynorphin and excitatory hypocretin/orexin neuropeptides. Journal of Neuroscience, 26(50), 13037–13047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Faraco J, Li R, Kadotani H, Rogers W, Lin X, … & Mignot E. (1999). The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell, 98(3), 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvin Y, Blanchard DC, & Blanchard RJ (2007). Rat 22 kHz ultrasonic vocalizations as alarm cries. Behavioural brain research, 182(2), 166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo YJ, Li YD, Wang L, Yang SR, Yuan XS, Wang J, … & Huang ZL. (2018). Nucleus accumbens controls wakefulness by a subpopulation of neurons expressing dopamine D 1 receptors. Nature communications, 9(1), 1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppi PH, Peyron C, & Fort P (2017). Not a single but multiple populations of GABAergic neurons control sleep. Sleep medicine reviews, 32, 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier EY, Abdalla M, Ahrens AM, Schallert T, & Duvauchelle CL (2012). The missing variable: ultrasonic vocalizations reveal hidden sensitization and tolerance-like effects during long-term cocaine administration. Psychopharmacology, 219(4), 1141–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler SV, Vazey EM, Beckley JT, Keistler CR, McGlinchey EM, Kaufling J, … & Aston-Jones G. (2014). Designer receptors show role for ventral pallidum input to ventral tegmental area in cocaine seeking. Nature neuroscience, 17(4), 577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus JN, Aschkenasi CJ, Lee CE, Chemelli RM, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M, & Elmquist JK (2001). Differential expression of orexin receptors 1 and 2 in the rat brain. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 435(1), 6–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, & Hikosaka O (2007). Lateral habenula as a source of negative reward signals in dopamine neurons. Nature, 447(7148), 1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavanji V, Perez-Leighton CE, Kotz CM, Billington CJ, Parthasarathy S, Sinton CM, & Teske JA (2015). Promotion of wakefulness and energy expenditure by orexin-A in the ventrolateral preoptic area. Sleep, 38(9), 1361–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHenry JA, Otis JM, Rossi MA, Robinson JE, Kosyk O, Miller NW, … & Stuber GD. (2017). Hormonal gain control of a medial preoptic area social reward circuit. Nature neuroscience, 20(3), 449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh TK, Barfield RJ, & Thomas D (1984). Electrophysiological and ultrasonic correlates of reproductive behavior in the male rat. Behavioral neuroscience, 98(6), 1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methippara MM, Alam MN, Szymusiak R, & McGinty D (2000). Effects of lateral preoptic area application of orexin-A on sleep–wakefulness. Neuroreport, 11(16), 3423–3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson D, Snyder E, Paradis E, Chengan-Liu M, Snavely DB, Hutzelmann J, … & Lines C. (2014). Safety and efficacy of suvorexant during 1-year treatment of insomnia with subsequent abrupt treatment discontinuation: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Neurology, 13(5), 461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirenowicz J, & Schultz W (1996). Preferential activation of midbrain dopamine neurons by appetitive rather than aversive stimuli. Nature, 379(6564), 449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman DE, & Aston-Jones G (2010). Orexin/hypocretin modulates response of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons to prefrontal activation: diurnal influences. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(46), 15585–15599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu P, Fuchs T, Saal DB, Sorg BA, Dong Y, & Panksepp J (2009). Repeated cocaine exposure induces sensitization of ultrasonic vocalization in rats. Neuroscience letters, 453(1), 31–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]