Abstract

This study was aimed at investigating the antioxidant properties and membrane stabilization effects of Mucuna pruriens leaves on sickle erythrocyte as a possible means of sickle cell disease management.

Pulverized plant material was extracted with methanol, filtered and concentrated at reduced pressure with a rotary evaporator. Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant studies of the extract were carried out using standard methods. Blood samples of volunteer sickle cell patients and healthy individuals used in the study were collected from the University of Nigeria Medical Centre and University campus community, Nsukka respectively. The genotypes of the individuals were confirmed by cellulose acetate paper electrophoresis. Water induced haemolysis of human red blood cell was used to assess membrane stabilization of the erythrocytes. Phytochemical result of the extract showed the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, proteins, terpenoids, saponins, cardiac glycosides and anthraquinones. Antioxidant vitamins C and E were present in concentrations of 495.36 mg/100 g and 101.03 mg/100 g respectively. The percentage (%) scavenging activity of the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH) and hydroxyl radical by the extract was significant. The extract exhibited membrane stabilization on both normal and sickle erythrocytes. The percentage (%) inhibition of haemolysis by the extract in both normal and sickle erythrocytes at different concentrations of 100, 200, 400, 600 and 800 μg/ml were significant and concentration dependent. We conclude that M. pruriens leaves have antioxidant properties and erythrocyte membrane stabilizing potentials and could be recommended for use in the management of patients with sickle cell anaemia.

Keywords: Mucuna pruriens, Membrane stabilization, Antioxidants, Erythrocytes, Haemolysis, Sickle cell

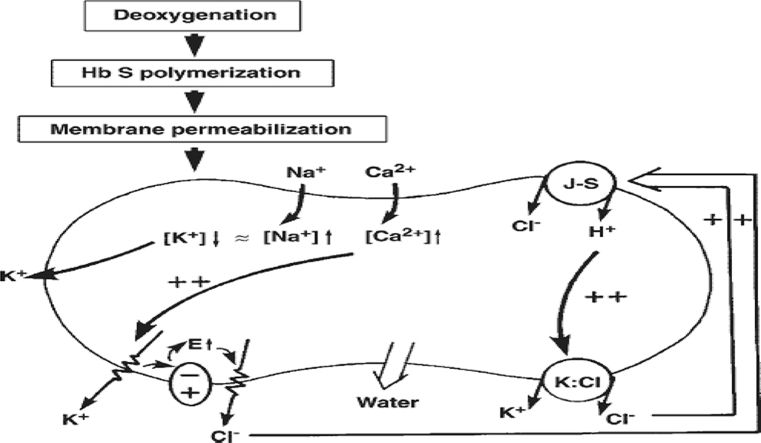

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Sickle cell disease is a group of inherited disorders of haemoglobin which include sickle cell anaemia (SCA), sickle cell haemoglobin C disease (HbSC) and sickle cell thalassaemia (Sβº and Sβ+). Of these, SCA is the most prevalent with clinical manifestations attributed to a point mutation in the amino acid globin chain of haemoglobin A by the substitution of a hydrophilic glutamic acid residue for a hydrophobic valine residue at the sixth position of the β-chain of haemoglobin molecule.1 The most important pathophysiologic processes that lead to sickle cell disease related complications result from a combination of haemolysis and vaso-occlusion.2 Haemolysis occurs as a result of repeated episodes of haemoglobin polymerization/depolymerization as sickle red blood cells pick up and release oxygen in the circulation. Haemolysis can occur both chronically and during acute painful vaso-occlusive crises and results in the release of substantial quantities of free haemoglobin into the vasculature.2 First-line clinical management of sickle cell anaemia includes: use of folic acid, amino acids as nutritional supplements, penicillin prophylaxis for prevention of infection and anti-malarial prophylaxis for malarial attack prevention. The faulty ‘S’ gene is not eradicated in treatment, rather the condition is managed and synthesis of red blood cells induced to stabilize the patient's haemoglobin level. Due to the high mortality rate of sickle cell patients, especially in children, there is need for rational drug development that must embrace not only synthetic drugs but also natural products (phyto-medicines/herbal drugs) with anti-sickling and erythrocyte membrane stabilizing potentials. These can be obtained from vast forest resources and used to effectively manage sickle cell patients and treat the anaemic condition accompanying the disorder.3

Mucuna pruriens is an annual climbing legume that grows 3–18 m in height, indigenous to tropical regions, especially Africa, India, and the West Indies. It is locally known as agbala or akurugba (Igbo), werepe or yerepe (Yoruba) and Karara (Hausa). It is wide spread over most of the subcontinent and is found in bushes, hedges, and dry-deciduous, low forests throughout the plains of India. The pods or legumes are hairy, thick, and leathery; shaped like violin sound holes; and contain four to six seeds. They are of a rich dark brown colour, and thickly covered with stiff hairs.4 In South-eastern Nigeria, the leaves of M. pruriens (Fig. 1) are considered excellent natural herbal blood boosters, used especially for debilitating conditions, acute blood loss and blood deficiency diseases.5 Studies have shown that crude aqueous seed extract of M. pruriens possess anti-sickling properties and thus could be employed in the management of sickle cell disease.1 This study was therefore aimed at investigating the effect of M. pruriens leaves on hypotonicity induced haemolysis of sickle erythrocytes as a possible means of sickle cell disease management.

Fig. 1.

Mucuna pruriens leaves.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Methanol (CH3OH-Sigma Aldrich, Germany), sodium metabisulphite (Na2S2O3- Chemphora Chemicals, Netherland), sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH2PO4.2H2O- Fisher, Scientific, USA), disodium hydrogen phosphate (Na2HPO4 – Fisher, Scientific, USA), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube (Nycodenz), 2% tween 80, sodium chloride (NaCl- BDH chemicals Ltd, Poole, England), sodium hydroxide (NaOH- May and Baker Laboratory Reagent), phosphoric acid (H3PO4).

2.2. Blood sample

Blood samples of volunteer sickle cell patients and healthy individuals used in this study were collected from the University of Nigeria Medical Centre, and University Campus community, Nsukka respectively. The genotypes of the individuals were confirmed by cellulose acetate paper electrophoresis. The venipuncture method was used for blood collection. Blood (3 ml) was drawn from each sickle cell patient and healthy individual using new syringes and needles, spirit swaps and a tourniquet. The blood samples were collected into EDTA and plain bottles and subsequently inverted gently for mixing. All experiments were performed within 72 h of blood collection and were in keeping with the guidelines published in the Helsinki Declaration for the Use of Human Subjects for research. Ethical clearance approval with the approval number UNN/FBS/EC/1001 was obtained from the Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Nigeria, Nsukka Committee on Ethics and Biosafety.

2.3. Plant material

The leaves of M. pruriens were collected from Nsukka environs. The plant material was identified by Mr. Ozioko, A.O. of the Bioresources Development and Conservation Programme (BDCP) Nsukka. The leaves were washed with distilled water, air dried at room temperature (28 ± 2 °C) for 3 days and reduced to smooth powder using a milling machine.

2.4. Extraction

The pulverized plant material (625 g) was macerated in 1563 ml of 99.8% methanol for 36 h, filtered with a clean muslin cloth and the residue re-soaked in 937 ml of methanol for 2 h and then filtered. The filtrates were pooled together and concentrated to 2% of its original volume by evaporating at reduced pressure in a rotary evaporator. The gel-like concentrate obtained was weighed and the percentage yield calculated. The extract was stored in an airtight plastic container in the refrigerator (4 °C) until used.

| (1) |

2.5. Qualitative phytochemical analyses

The phytochemical analysis of M. pruriens leaves was carried out according to the method of Harborne6 and Trease and Evans.7

2.6. Antioxidant studies

2.6.1. DPPH radical-scavenging activity of the extract

Scavenging of 1,1 diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazil (DPPH) free radicals by the extract was assessed according to the method reported by Oyaizu.8 To 3 ml of the diluted extract, 1 ml of methanol solution of DPPH 0.1 mM was added. The mixture was kept in the dark at room temperature for 30 min and the absorbance was read at 517 nm against a blank. The equation below was used to determine the percentage of the radical scavenging activity of the extract.

Percentage of radical-scavenging activity = [(OD control - OD sample)/OD control] × 100.

The EC50 value (μg/ml) is the effective concentration at which DPPH radicals were scavenged by 50% and the value was obtained by interpolation from linear regression analysis.

2.6.2. Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) of the extract

The FRAP method was used to determine the total antioxidant activity of the extract. This experiment measures the reduction of ferric ion to the ferrous form in the presence of antioxidant compounds. It was carried out using the method described by Trease and Evans.9 The fresh FRAP reagent consisted of 500 ml of acetate buffer (300 mM pH 3, 6), 50 ml of 2, 4, 6- Tri (2- pyridyl)-s-triazin (TPTZ) (10 mM), and 50 ml of FeCl3·6H2O (50 mM). For the assay, 75 μl of the extract was mixed with 2 ml of FRAP reagent and the optical density was read after 2 min at 593 nm against the blank.

2.6.3. Hydroxyl radical-scavenging activity of the extract

The scavenging activity of the extract against hydroxyl radical was measured according to a previously described method by Mensor et al.10 In 1.5 ml of the diluted extract, 60 μl of FeCl3 (1 mM), 90 μl of 1,10- phenanthroline (1 mM), 2.4 ml of 0.2 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.8 and 150 μl of H2O2 (0.17 M) were added respectively. The mixture was then homogenized and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. The absorbance was read at 560 nm against the blank. The percentage of the radical scavenging activity of the extract was calculated from the equation below:

Percentage of radical scavenging activity = [(OD control - OD sample)/OD control] × 100.

The extract concentration providing 50% inhibition (IC50) was calculated and obtained by interpolation from linear regression analysis.

2.6.4. Determination of the ascorbic acid content of the extract

The determination of the ascorbic acid concentration of the extract was carried out by the method of Nwaoguikpe et al.11 Ascorbic acid standard was prepared containing 1 g/dm3 of vitamin C. A burette was filled with a solution of 2, 6-dihlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) of concentration 0.01%. Ten milliliters (10 ml) of ascorbic acid was acidified with two drops of dilute HCl in a beaker. The indophenol solution was then titrated against the ascorbic acid until a permanent pink colour developed. An aliquot (1 cm3) of the indophenol solution was equivalent to 10 mg vitamin C. Having standardized the indophenols solution, 10 cm3 of the test solution (extract) was taken and treated as above.

2.6.5. Determination of vitamin E content of the extract

This assay was carried out according to the method of Okwu.12 A quantity of the sample (2.5 ml) was placed in two test tubes; 0.5 ml nitric acid was added to each tube and placed in boiling water for 3 min. Test tubes were cooled and allowed to stand in the dark for 15 min. The volume of solution in each test tube was made up to 5 ml with ethanol and absorbance measured at 470 nm. The concentration of vitamin E in the test solution was determined using a calibration curve of standard vitamin E concentration. A blank preparation containing 2.5 ml of distilled water was put in a test tube and 0.5 ml nitric acid added and placed in a boiling water bath for 3 min. The tube was cooled and kept in the dark. The standard was prepared using a capsule of 1000 mg vitamin E.

2.7. Membrane stabilization studies

Water induced haemolysis of human red blood cell was used to assess membrane stabilization using the method described by Shinde et al.13

2.7.1. Preparation of erythrocyte suspension

Fresh whole blood (3 ml) collected from healthy HbAA volunteers as well as HbSS patients were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. A volume of saline equivalent to that of the supernatant was used to dissolve the red blood pellets. The volume of the dissolved red blood pellets was measured and reconstituted as a 40% v/v suspension with isotonic buffer (10 mM Sodium Phosphate buffer, pH 7.4). The buffer solution contained 0.2 g of NaH2PO4, 1.15 g of Na2HPO4 and 9 g of NaCl in 1 L of distilled water. The reconstituted red blood cell (re-suspended supernatant) was used as such.

2.7.2. Hypotonicity induced-haemolysis of red blood cell

Samples of the extract used for the test were dissolved in distilled water (hypotonic solution). The hypotonic solution (5 ml) contained graded doses of the extracts (100, 200, 400, 600, and 800 μg/ml) and was put into duplicate pairs (per dose) of the centrifuge tubes. An isotonic solution (5 ml) containing graded doses of the extract (100, 200, 400, 600 and 800 μg/ml) was put into duplicate pairs (per dose) of the centrifuge tube. Control tubes contained 5 ml of the vehicle (distilled water) and 5 ml of 200 μg/ml of indomethacin respectively. Erythrocyte suspension (0.1 ml) was added to each of the tubes and mixed gently. The mixture was incubated for 1 h at room temperature (25 °C) and centrifuged afterwards for 3 min at 1300 g. Absorbance (OD) of the haemoglobin content of the supernatant was estimated at 540 nm using a spectrophotometer. Percentage haemolysis was calculated by assuming the haemolysis produced in the presence of distilled water as 100%.

The percent inhibition of haemolysis of the extract was calculated thus

| (2) |

where OD1 = Absorbance of test sample in isotonic solution.

OD2 = Absorbance of test sample in hypotonic solution.

OD3 = Absorbance of control sample in hypotonic solution.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data obtained were analysed using Statistical Product and Services Solution (SPSS) version 20 and the results expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Significant differences of the results were established by one-way analysis of variance ANOVA and the acceptance level of significance for the results was p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Percentage yield of the Methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves

Table 1 shows the percentage yield of the methanol extract of the plant relative to the weight of the plant sample before extraction. The dry weight (625 g) of the pulverized sample gave a percentage yield of 12.16%.

Table 1.

Percentage yield of the methanol extract of Mucuna pruriens leaves.

| Weight of dry pulverized sample (g) | weight of extract (g) | Percentage yield (%) | Colour of extract |

|---|---|---|---|

| 625 | 76 | 12.16 | Dark green |

3.2. Qualitative phytochemical composition of the Methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves

Table 2 shows result of the phytochemical screening of the plant extract which revealed the presence of some important bioactive compounds such as flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, glycosides, terpenoids, saponins, proteins and anthraquinones.

Table 2.

Qualitative phytochemical composition of the methanol extract of Mucuna pruriens leaves.

| Phytochemicals | Bioavailability |

|---|---|

| Alkaloids | ++ |

| Flavonoids | +++ |

| Tannins | ++ |

| Proteins | ++ |

| Terpenoids | ++ |

| Saponins | +++ |

| Glycosides | + |

| Anthraquinone | + |

Key.

+: present in small concentration.

++: present in moderately high concentration.

+++: present in very high concentration.

3.3. Antioxidant profile

3.3.1. Antioxidant vitamin content of the Methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves

Table 3 shows the concentrations (mg/100 g) of antioxidant vitamins C and E found in the plant extract. The concentration of vitamin C was 495.36 mg/100 g while that of vitamin E was 101.03 mg/100 g respectively.

Table 3.

Concentrations of vitamins C and E of the methanol extract of Mucuna pruriens leaves.

| Vitamin Constituents | Amount (mg/100 g) |

|---|---|

| C | 495.36 ± 0.00 |

| E | 101.03 ± 0.00 |

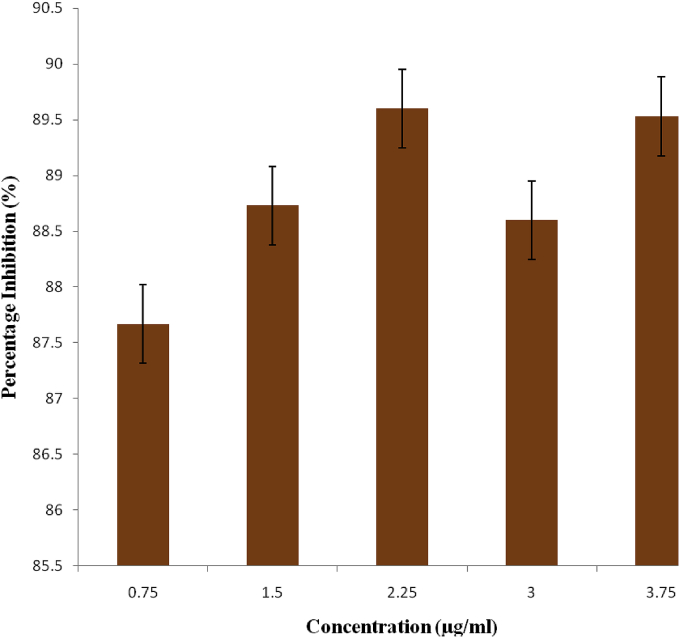

3.3.2. 1,1 diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazil (DPPH) free radical scavenging activity

The anti-oxidant activity of the methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves using DPPH assay was shown in Fig. 2. The various concentrations of the extract exhbited significant antioxidant activity. The % scavenging activity of the DPPH radical by the extract for the different concentrations of 0.75, 1.5, 2.25, 3.0 and 3.75 μg/ml were 87.67, 88.73, 89.60, 88.60 and 89.53% respectively.

Fig. 2.

(DPPH) Free Radical-Scavenging Activity of methanol extract of Mucuna pruriens leaves.

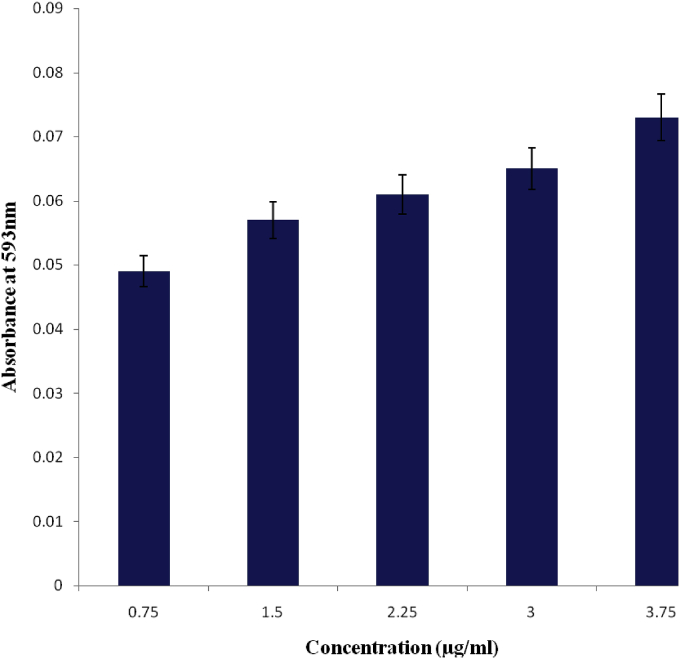

3.3.3. Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) activity

Fig. 3 shows the result for ferric ion reducing activities of the methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves at the different concentrations. The absorbance increase was proportional to the antioxidant scavenging power of the extract. The reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ at different concentrations (0.75–3.75 μg/ml) of the extract was concentration dependent.

Fig. 3.

Ferric reducing antioxidant power of methanol extract of Mucuna pruriens leaves.

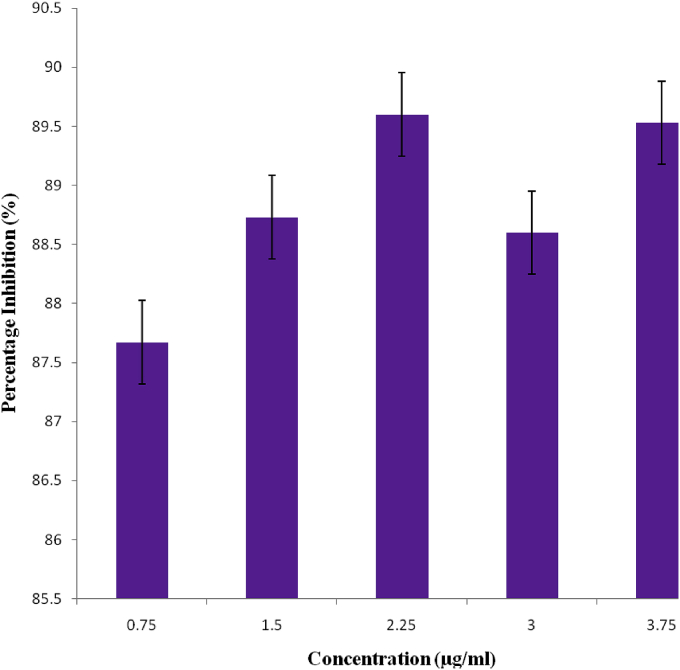

3.3.4. Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of the methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves at different concentrations was shown in Fig. 4. The extract exhibited concentration dependent scavenging activity. The percentage (%) scavenging activity of hydroxyl radical by the extract for the different concentrations (0.75, 1.5, 2.25, 3.0 and 3.75 μg/ml) of the extract were 36.20, 47.15, 63.54, 46.88 and 69.27% respectively.

Fig. 4.

Hydroxyl radical-scavenging activity of the methanol extract of Mucuna pruriens leaves.

3.3.5. EC50 values for DPPH and Hydroxyl ion scavenging activity

Table 4 shows antioxidant results reported as the EC50 (effective concentration), ie. the amount of antioxidant required to decrease by 50% the initial DPPH and hydroxyl ion concentration. A lower EC50 was an indication of a higher antioxidant activity.

Table 4.

EC50 values for DPPH and hydroxyl ion-scavenging activity.

| SampleStandard | DPPH (μg/ml) | Hydroxyl Assay (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard | 1.16 | 1.84 |

| Mucuna pruriens | 1.84 | 2.35 |

3.4. Membrane stabilization profile

3.4.1. Effect of the Methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves on hypotonicity-induced haemolysis of sickle erythrocytes (HbSS)

Result in Table 5 show the in-vitro membrane stabilization of methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves and indomethacin (standard drug) on human sickle erythrocytes exposed to hypotonic solution (induced lysis). The extract exhibited monophasic mode of protection on the sickle erythrocytes i.e. the extract protected red blood cells from induced lysis at all the concentrations used in a dose dependent manner. The percentage (%) inhibition of haemolysis in sickle erythrocytes by the extract at different concentrations of 100, 200, 400, 600 and 800 μg/ml were 2.24, 7.57, 62.50, 87.34 and 89.45% respectively. The 600 and 800 μg concentrations gave higher percentage inhibition of haemolysis than the standard drug which was 85.02%.

Table 5.

Effect of methanol extract of Mucuna pruriens leaves on hypotonicity-induced haemolysis of sickle RBC (HbSS).

| Treatment | Conc. (μg/ml) | Mean absorbance ± SD |

Percentage inhibition of haemolysis(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotonic solution | Isotonic solution | |||

| Control | - | 0.530 ± 0.00 a | 0.129 ± 0.00 b | |

| Extract | 100 | 0.519 ± 0.00 a | 0.039 ± 0.00 a | 2.24 |

| 200 | 0.493 ± 0.01 a | 0.041 ± 0.00 a | 7.57 | |

| 400 | 0.420 ± 0.00 b | 0.354 ± 0.02 c | 62.50 | |

| 600 | 0.330 ± 0.01 c | 0.301 ± 0.02 c | 87.34 | |

| 800 | 0.301 ± 0.01 c | 0.274 ± 0.02 c | 89.45 | |

| Indomethacin | 200 | 0.269 ± 0.00 c | 0.161 ± 0.00 b | 85.02 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Mean values having different letters as superscripts down the column are considered significantly different (p < 0.05).

3.4.2. Effect of Methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves on hypotonicity-induced haemolysis of normal erythrocytes (HbAA)

Result in Table 6 show the in-vitro membrane stabilization of methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves and indomethacin (standard drug) on normal human erythrocytes exposed to hypotonic induced lysis. The extract also exhibited monophasic mode of protection on the normal erythrocytes. The percentage inhibition of haemolysis in normal adult erythrocytes by the extract at different concentrations of 100, 200, 400, 600 and 800 μg/ml were 2.91, 8.66, 23.37, 52.36 and 69.31% respectively. The standard drug with percentage inhibition of 85.02% had higher efficacy in inhibiting hypotonic induced haemolysis of normal erythrocytes than the extract at the different concentrations.

Table 6.

Effect of methanol extract of Mucuna pruriens leaves on hypotonicity-induced haemolysis of normal RBC (HbAA).

| Treatment | Conc. (μg/ml) | Mean absorbance ± SD |

Percentage inhibition of haemolysis(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotonic solution | Isotonic solution | |||

| Control | - | 0.882 ± 0.00 a | 0.167 ± 0.00 a | |

| Extract | 100 | 0.861 ± 0.02 a | 0.162 ± 0.01 a | 2.91 |

| 200 | 0.820 ± 0.01 a | 0.166 ± 0.00 a | 8.66 | |

| 400 | 0.728 ± 0.01 a | 0.223 ± 0.01 b | 23.37 | |

| 600 | 0.627 ± 0.01 b | 0.395 ± 0.01 c | 52.36 | |

| 800 | 0.541 ± 0.02 b | 0.390 ± 0.01 c | 69.31 | |

| Indomethacin | 200 | 0.269 ± 0.00 c | 0.161 ± 0.00 a | 85.02 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Mean values having different letters as superscripts down the column are considered significantly different (p < 0.05).

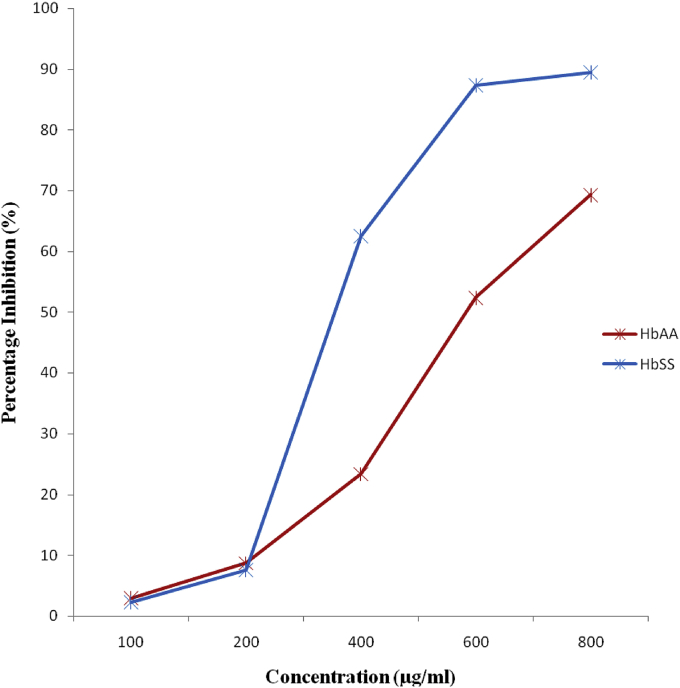

3.4.3. Comparison of membrane stabilization potential of Methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves on both normal and sickle erythrocytes

Fig. 5 shows a comparison of the membrane stabilization effect of methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves on both sickle and normal erythrocytes. The extract had a higher membrane stabilization effect on the normal erythrocytes than the sickle erythrocytes at the lower concentrations of 100 μg/ml (HbAA: 2.91%; HbSS: 2.24%) and 200 μg/ml (HbAA: 8.66%; HbSS: 7.57%), whereas, a higher stabilization effect was observed on the sickle erythrocytes than the normal erythrocytes at the higher concentrations of 400 μg/ml (HbSS: 62.50%; HbAA: 23.37%), 600 μg/ml (HbSS: 87.34%; HbAA: 52.31%) and 800 μg/ml concentrations (HbSS: 89.45%; HbAA: 69.31%) respectively.

Fig. 5.

Percentage inhibition of haemolysis in sickle and normal erythrocytes by methanol extract of Mucuna pruriens leaves.

4. Discussion

Membrane stabilization is a process of maintaining the integrity of biological membranes such as erythrocyte and lysosomal membranes against osmotic and heat-induced lysis.14 In the present study, stabilization of erythrocyte membranes exposed to hypotonic induced lysis was employed due to its simplicity and reproducibility. When red blood cells are placed in hypotonic solution in which osmolarity is diminished, the gain in red blood cell water is both instantaneous and quantitative. This phenomenon is put into practical use in the red blood cell osmotic fragility test, which determines the release of haemoglobin from red blood cells in hypotonic sodium chloride (NaCl) solution. In this study, the membrane stabilization effect of various concentrations of the extract of M. pruriens leaves on both AA and SS blood cells exposed to hypotonic induced lysis was determined. The mode of response of both erythrocyte types was monophasic. The extract exhibited membrane stabilization of 2.24% and 89.45% for HbSS as minimum and maximum percentage activities, and 2.91% and 69.31% for HbAA as minimum and maximum percentage activities respectively, while the standard drug (indomethacin) exerted membrane stabilization of 85.02% at 200 μg/ml. Reports have shown that oxidative damage of erythrocyte membrane is the primary cause of reduced capacity of the red blood cells to withstand mechanical and osmotic stress.15 Antioxidant phytochemicals such as flavonoids and tannins have been reported to prevent oxidative damage. The mode of action of the extracts and fractions with membrane stabilization potentials could be attributed to their binding to the erythrocyte membranes with subsequent alteration of the surface charges of the cells. This may prevent physical interaction with aggregating agents or promote dispersal by mutual repulsion of like charges which are involved in the haemolysis of red blood cells. Reports have shown that certain saponins and flavonoids exert profound stabilizing effect on lysosomal membrane both in vivo and in vitro, while tannins and saponins possess ability to bind cations, thereby stabilizing erythrocyte membranes and other biological macromolecules.16, 17 Presence of these phytochemicals suggests that the extract contains constituents that protected the erythrocytes membranes effectively.

In-vitro antioxidant screening, FRAP assay, DPPH and hydroxyl radical scavenging activities, were carried out for the methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves. Vitamin C, E, and beta carotene are among the most widely studied dietary antioxidants. Vitamin C, considered the most important water-soluble antioxidant in extracellular fluids is capable of neutralizing reactive oxygen species in the aqueous phase before lipid peroxidation is initiated.18 Vitamin E; the generic name for the tocopherols and tocotrienols, a major lipid-soluble antioxidant, is the most effective chain-breaking antioxidant within the cell membrane where it protects membrane fatty acids from lipid peroxidation. Membrane lipids are rich in unsaturated fatty acids, specifically-linoleic acid and arachidonic acid, which are most susceptible to oxidative processes.19 Tocotrienols have specialized roles in protecting neurons from damage and reducing cholesterol by inhibiting the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase. Thus, M. pruriens leaves which are rich sources of these antioxidant vitamins could be useful in the prevention of red cell membrane destruction in sickle cell disease as well as protection against microbial infections.

Being a stable free radical, DPPH (1,1 diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazil) is frequently used to determine radical-scavenging activity of natural compounds. In its radical form, DPPH absorbs at 517 nm, but upon reduction with an antioxidant, its absorption decreases due to the formation of its non-radical form, DPPH–H.20 Thus, radical scavenging activity in the presence of a hydrogen donating antioxidant can be monitored as a decrease in absorbance of DPPH solution. In this study, the DPPH radical scavenging activity of the extract of M. pruriens leaves was not concentration dependent. The antioxidant activity of the extract was expressed as EC50; the effective concentration (μg/ml) of extract that inhibited the formation of DPPH radicals by 50%. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control. The EC50 for the standard and extract were 1.16 and 1.84 μg/ml respectively showing that the extract had considerable DPPH radical scavenging activity and could serve as a good antioxidant. Research has shown that many flavonoids and related polyphenols contribute significantly to the antioxidant activity of medicinal plants.21 Due to the presence of the conjugated ring structures and hydroxyl groups; many phenolic compounds have the potential to function as antioxidants by scavenging or stabilizing free radicals involved in oxidative processes through hydrogenation or by complexing with oxidizing species.22

FRAP assay measures the reducing potential of an antioxidant reacting with a ferric tripyridyltriazine [Fe3+-TPTZ] complex to produce a coloured ferrous tripyridyltriazine [Fe2+-TPTZ].23 Generally, the reducing properties are associated with the presence of compounds which exert their action by breaking the free radical chain and donating a hydrogen atom which is an important mechanism of phenolic antioxidant action.24 In the FRAP assay, the absorbance of the methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves significantly increased with increasing concentration due to the formation of the Fe2+-TPTZ complex. This could be attributed to the presence in the extract of flavonoids and tannins which are phenolic compounds, thus, the extract may be able to donate electrons to stabilize free radicals in biological systems.

The hydroxyl radical is the most reactive of the reactive oxygen species, and it induces severe damage in adjacent biomolecules.25 The hydroxyl radical can cause oxidative damage to DNA, lipids and proteins.26 The methanol extract exhibited •OH scavenging activity (%) in a concentration dependent manner with an EC50 value of 2.35 μg/ml while that of the standard (α-tocopherol) was 1.73 μg/ml. Hence, the extract could be considered as a good scavenger of hydroxyl radicals and may be utilized in reducing oxidative stress associated with sickle cell disease. Results from this study has shown that the extract of M. pruriens leaves improved the ability of the red blood cells to take up water without lysis occurring due to its membrane stabilizing activity which may have been aided by the presence of the tannins, saponins and flavonoids in the extract. Vitamin E deficiency leads to red cell haemolysis, and supplemental vitamin E has been shown to improve red cell survival in some patients with glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, β-thalassemia and sickle cell anaemia.27 Thus, the vitamin E present in this extract may also have played an important role in preventing the hypotonic induced lysis of the red blood cells.

Thus, from the data presented in this work, methanol extract of M. pruriens leaves has antioxidant and membrane stabilizing potentials and could be recommended for use as food and protein source, especially for patients with sickle cell anaemia.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

OFCN conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination. ONI carried out the experimental studies. CAA participated in the coordination of the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the technical staff of the Department of Biochemistry, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, for their assistance in the laboratory.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Center for Food and Biomolecules, National Taiwan University.

References

- 1.Ojiako O.A., Anugweje K., Igwe C.U., Ogbuji C.A., Alisi C.S., Ujowundu C.O. Anti-sickling potential and amino acid profile of extracts from Nigerian Lagenaria sphaerica, Mucuna pruriens and Cucurbita pepo Var Styriaca. J Res Biochem. 2012;1:029–035. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiter C.D., Wang X., Tanus-Santos J.E., Hogg N., Cannon R.O., Schechter A.N., Gladwin M.T. Cell-free haemoglobin limits nitric oxide bioavailability in sickle-cell disease. Nat Med. 2002;8:1383–1389. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imaga N.O.A., Shaire E.A., Ogbeide S., Samuel K.A. In vitro biochemical investigations of the effects of Carica papaya and Fagara zanthoxyloides on antioxidant status and sickle erythrocytes. Afr J Biochem Res. 2011;5(8):226–236. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lampariello R.L., Cortelazzo A., Guerranti R., Sticozzi C., Valacchi G. The magic velvet bean of Mucuna pruriens. J Tradit Compl Altern Med. 2012;2(4):331–339. doi: 10.1016/s2225-4110(16)30119-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obadoni B.O., Ochuko P.O. Phytochemical studies and comparative efficacy of the crude extracts of some haemostatic plants in Edo and Delta states of Nigeria. Glob J Pure Appl Sci. 2001;8:203–208. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harborne J.B. Chapman and Hall; New York: 1973. Phytochemical Methods: A Guide to Modern Techniques of Plant Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trease G.E., Evan W.C. 15th Edn. Saunders Publishers; London: 2002. “Textbook of Pharmacognosy”; pp. 229–393. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oyaizu M. Studies on products of browing reaction: anti-oxidative activities of products of browing reaction prepared from glucosamine. Jpn J Nutr. 1986;44:307–315. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trease G.E., Evans W.C. Pharmacognosy. Bailliere Tindal, London. In: Urquiaga I., Leighton F., editors. Plant Polyphenol Antioxidants and Oxidative Stress. vol. 33. 2000. pp. 9716–9760. (Biological Research). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mensor L., Menezes F., Leitao G., Reis A., Dos Santos T., Coube C., Leitão S.G. Screening of Brazilian plant extracts for antioxidant activity by the use of DPPH free radical method. Phytother Res. 2001;15:27–130. doi: 10.1002/ptr.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nwaoguikpe R.N., Ekeke G.I., Uwakwe A.A. University of PortHarcourt; Nigeria: 1999. The Effects of Extracts of Some Foodstuffs on Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Activity and Haemoglobin Polymerization of Sickle Cell Blood. (Ph.D. thesis) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okwu D.E. Phytochemicals and vitamins content of indigenous spices of South-Eastern Nigeria. J Sustain Agric Environ. 2004;6:30–34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shinde U.A., Phadke A.S., Nair A.M., Mungantiwar A.A., Dikshit V.J., Sarsf M.N. Membrane stabilization activity- A possible mechanism of action for the anti-inflammatory activity of Cedrus deodara wood oil. Fitoterapia. 1989;70:251–257. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadique J., Al-Rqodah W.A., Baghhath M.F., El-Ginay R.R. The bioactivity of certain medicinal plants on the stabilization of the RBC system. Fitoterapia. 1989;66:525–532. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chikezie P.C., Uwakwe A.A., Monago C.C. Comparative osmotic fragility of three erythrocyte genotypes (HbAA, HbAS and HbSS) of male participants administered with five antimalarial drugs. Afr J Biochem Res. 2010;4(3):57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Middleton E. Biological properties of plant flavonoids: an overview. Int J Pharmacogn. 1996;34:344–348. [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Shabrany O.A., El-Gindi O.D., Melek F.R., Abdel-Khalk S.M., Haggig M.M. Biological properties of saponin mixtures of Fagonia cretica and Fagonia mollis. Fitoterapia. 1997;LXVIII:219–222. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sies H., Stahl W., Sundquist A.R. Antioxidant functions of vitamins. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;669:7–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb17085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nebavi S.M., Ebrahimzadeh M.A., Nebavi S.F., Bahramcan F. In vitro antioxidant activity of Phytolacca americanaberries. Pharmacologyonline. 2009;1:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blois M.S. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958;181:1199–1201. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan A.K., Khan R.M., Sahreen S., Ahmed A. Evaluation of phenolic contents and antioxidant activity of various solvent extracts of Sonchus asper (L.) Hill. Chem Central J. 2012;6:12–23. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amic D., Davidovic-Amic D., Beslo D., Trinajstic N. Structure-radical scavenging activity relationship of flavonoids. Croat Chem Acta. 2003;76:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benzie I.F., Strain J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of ‘‘antioxidant power’’: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239:70–76. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duh P., Du P., Yen G. Action of methanolic extract of mung bean hull as inhibitors of lipid peroxidation and non-lipid oxidative damage. Food Chem Toxicol. 1999;37:1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(99)00096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gutteridge M.C. Reactivity of hydroxyl and hydroxyl-like radicals discriminated by release of thiobarbituric acid reactive material from deoxy sugars, nucleosides and benzoate. Biochem J. 1984;224:761–767. doi: 10.1042/bj2240761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spencer J.P.E., Jenner A., Aruoma O.I. Intense oxidative DNA damage promoted by L-DOPA and its metabolites, implications for neurodegenerative disease. FEBS Lett. 1984;353:246–250. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delvin T.M. Textbook of Biochemistry with Clinical Correlations. 2ndEdn. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1986. Hemoglobin and myoglobin; pp. 76–90. [Google Scholar]