Abstract

We present two cases of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma (PPC) treated with Nivolumab. A 57‐year‐old man presented with a 3.5‐cm mass in the left lower lobe. Left lower lobectomy and lymph node dissection were performed. Histological diagnosis was stage IIIA (pT2bN2M0) PPC. The tumour relapsed two months later and he was treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel, but his condition became progressive and nonresponsive after one cycle. We used nivolumab as second line. Repeat chest X‐ray showed impressive reduction of relapse lesions seven days after the start of nivolumab therapy. Our second case is a 50‐year‐old man who presented with a 3.7‐cm mass in the right lower lobe and submucosal tumour in the colon. Endobronchial ultrasound‐guided transbronchial needle aspiration biopsy (EBUS‐TBNA) and colon biopsy yield the diagnosis of PPC and metastatic colon cancer. He was treated with cisplatin plus pemetrexed. His disease proved resistant and we used nivolumab as second line. He showed partial response following four cycles.

Keywords: Nivolumab, NSCLC, PD‐L1, pleomorphic carcinoma, sarcomatoid

Introduction

Pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma (PPC) is a rare type of poorly differentiated non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that is classified under sarcomatoid carcinoma. Definitive diagnosis can usually only be made postoperatively by histopathology of the resected tumour. PPC shows a more aggressive clinical course than other types of NSCLC, and is resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nivolumab is a fully human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that targets the programmed death 1 (PD‐1) receptor on immune cells and disturbs PD‐1‐mediated signalling recalling anti‐tumour immunity. A clinical trial comparing nivolumab with docetaxel in advanced non‐squamous NSCLC revealed superior overall survival in programmed death‐ligand 1 (PD‐L1) positive patients treated with nivolumab 1. Although previous studies have reported a high frequency of expression of PD‐L1 in PPC, and higher expression levels of PD‐L1 in the sarcomatous than the carcinomatous components of these tumours 2, the response of NSCLCs containing sarcomatoid components to treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors has not yet been investigated. Herein, we describe two patients with advanced NSCLC, including; one in whom the definitive diagnosis of PPC was made by histopathology of the resected tumour and another in whom the diagnosis of “favor adenocarcinoma containing sarcomatoid components” was made by tissue biopsy. Both were resistant to first line platinum‐based chemotherapy, but responded dramatically to second line nivolumab therapy.

Case Report

Case 1

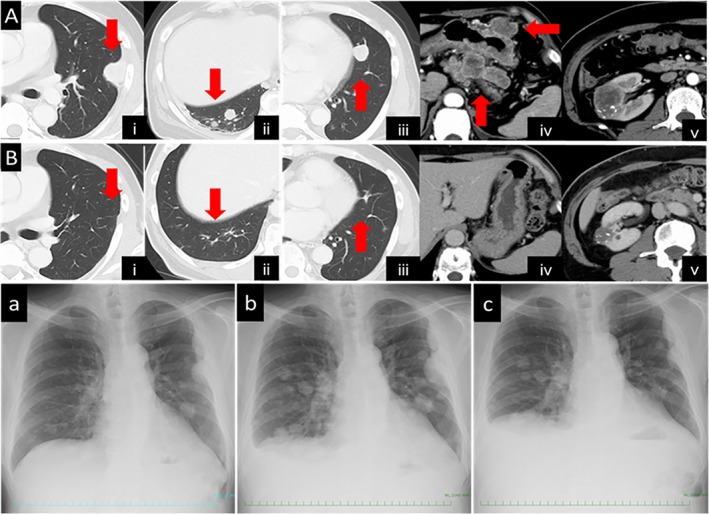

This patient was a 57‐year‐old man who was referred to our hospital in December 2015 for evaluation of a pulmonary mass in the left lower lobe and a right renal mass. His past medical history included right‐sided pneumothorax and surgery at the age of 48 years. The right renal mass had been detected by computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and had gradually increased in size over eight years. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a right renal mass with a tumour pseudocapsule that was suspected as being a low‐grade renal cell carcinoma. He had smoked 28 packs/year before quitting at 48 years of age. There was no family history of neoplasms. He was diagnosed by bronchoscopy and biopsy as having NSCLC‐not otherwise specified. Left lower lobectomy was performed, and histopathological examination of the resected specimen revealed that the tumour was composed of poorly differentiated malignant cells, including spindle‐shaped and giant cells. There was evidence of mediastinal lymph node metastasis. The patient was diagnosed as having PPC, stage IIIA (pT2bN2M0). He was scheduled to undergo operation for the renal mass, hence did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy after the lobectomy. Two months after the chest surgery, he was admitted to our hospital complaining of weakness and anaemia. CT of the chest and abdomen revealed multiple lung, pleural, bone and liver metastases, enlargement of lymph nodes around the stomach and mesenterium, and irregular enhancement within the gastric corpus and small bowel (Fig. 1A (i–iv)). The renal tumour was larger in size as compared to that in the previous imaging examination (Fig. 1A (v)). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (GIE) revealed a 5.0‐cm mass with a central crater along the greater curvature of the stomach. The histopathological diagnosis was gastric metastasis from the PPC. After this confirmation of the diagnosis of PPC recurrence, the patient received treatment with carboplatin plus paclitaxel, however, after one cycle of this treatment, an obvious increase in the sizes of the chest metastatic lesions was observed on plain chest radiography (Fig. 1A, B). Therefore, the patient was initiated on second‐line therapy with nivolumab at the dose of 3 mg/kg administered every two weeks. A repeat plain chest X‐ray obtained seven days after the start of nivolumab therapy revealed an impressive reduction in the sizes of the pulmonary and pleural lesions (Fig. 1C). CT performed 17 and 78 days after the start of nivolumab therapy demonstrated marked regression of the pulmonary, pleural, and liver metastases, and also of the lymph nodes around the stomach and peritoneum (Fig. 1B (i–iv)). The right renal mass had also shrunk in size (Fig. 1B (v)). Follow‐up GIE performed 53 days after the start of nivolumab therapy revealed shrinkage of the large ulcerated mass lesion in the stomach. To date (28 months after nivolumab therapy was started), the patient continues to receive nivolumab.

Figure 1.

(A) Computed tomography (CT) revealed recurrent lesions, including in the pleura (i), lungs (ii, iii) and lymph nodes (iv) (arrows), and increase in the size of the right renal mass (v). (B) CT obtained on day 78 after the start of nivolumab treatment showing shrinkage of the recurrent lesions mentioned above (i, ii, iii, iv) (arrows) and also of the right renal mass (v). (a) Chest X ray obtained before the carboplatin plus paclitaxel treatment. (b) Chest X ray obtained before the start of nivolumab treatment. (c) Chest X ray obtained on day 7 after the start of nivolumab treatment.

Case 2

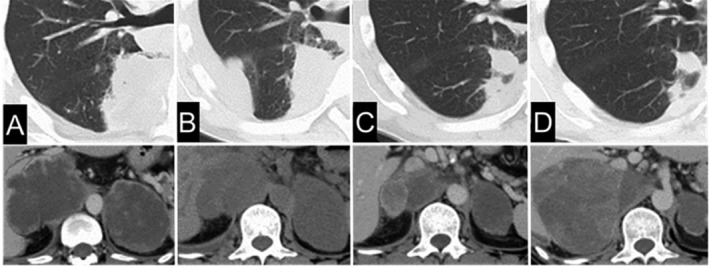

This patient was a 50‐year‐old man who was referred to our hospital in November 2015 for evaluation of a pulmonary mass in the right lower lobe. His past medical history included hypertension and nephrolithiasis. He had smoked 30 packs/year before quitting at 49 years of age. There was no family history of neoplasms. Positron emission tomography‐CT (PET‐CT) revealed increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the lung mass, left adrenal grand, ascending colon and mediastinal and abdominal lymph nodes. Colon biopsy and endobronchial ultrasound‐guided transbronchial needle aspiration biopsy (EBUS‐TBNA) of the mediastinal lymph nodes were performed. Histopathological examination of both specimens showed poorly differentiated malignant cells, including spindle‐shaped cells. Immunocytochemical analysis showed that the tumour cells were diffusely positive for cytokeratin 7, but negative for cytokeratin 20, suggesting the diagnosis of metastatic pleomorphic carcinoma of pulmonary origin. The tumour cells in the mediastinal lymph node specimens also showed positive staining for thyroid transcription factor‐1 and pulmonary surfactant protein‐A, which led to the diagnosis of primary right lower lung “favor adenocarcinoma with sarcomatoid features” with colonic metastasis. He was started on treatment with cisplatin plus pemetrexed, however, after just two cycles, the patient was found to be resistant to the treatment, with marked increase in the sizes of the adrenal gland metastases bilaterally, and deterioration of the performance status (PS) to 2 (Fig. 2A). Therefore, the patient was initiated on second‐line treatment with nivolumab at the dose of 3 mg/kg administered every two weeks. CT evaluation 41 and 112 days after the start of nivolumab therapy showed reduction in the sizes of the metastatic lesions and partial response, with improvement of the PS to 0 (Fig. 2B, C). In the evaluation conducted 196 days after the start of nivolumab therapy, while all other metastatic lesions had continued to diminish in size the right adrenal gland mass alone had become bulkier (Fig. 2D). Neither the third treatment with docetaxel nor the fourth treatment with S‐1 (tegafur, gimeracil, oteracil) was effective and the patient died. To evaluate the expression of the programmed death ligand 1 (PD‐L1) receptor after the administration of nivolumab, the tumour samples, including the surgically resected specimen in case 1 and the EBUS‐TBNA specimen from the lymph node tissue in case 2, were subjected to immunohistochemistry (IHC) and found to be strongly positive (≥50%). In case 1, the PD‐L1 expression showed strong positivity in both the sarcomatous and carcinomatous portions; however, the sarcomatoid component was stained slightly stronger than the adenocarcinoma component in case 2.

Figure 2.

(A) Computed tomography (CT) before nivolumab treatment. (B) CT on day 41 after the start of nivolumab treatment. (C) CT on day 112 after the start of nivolumab treatment. (D) CT on day 196 after the start of nivolumab treatment.

Discussion

Palliative chemotherapy commonly used for NSCLC is seldom effective for PPC, and new therapeutic strategies are required. In our two cases described here, one was diagnosed as having PPC by histopathological examination of the surgically resected specimen, and the other was diagnosed as having “favor adenocarcinoma containing sarcomatoid components” by tissue biopsy. Both were resistant to platinum‐based chemotherapy, but responded dramatically to nivolumab therapy. Blockade of immune checkpoints with therapies targeting the PD‐1 pathway has been validated as a therapeutic approach for patients with NSCLC 1. Previous studies have identified PD‐L1 expression at a high frequency in PPC, and also that the expression levels were significantly higher in the sarcomatous than the carcinomatous components of these tumours 2, suggesting the potential efficacy of anti‐PD‐1 antibody therapy. Several previous case reports have been published concerning the response to nivolumab therapy in patients with PPC 3, 4, 5. As in the present cases, all previous cases showed resistance to surgical treatment or cytotoxic chemotherapy, and their condition rapidly deteriorated, but a dramatic response to nivolumab was achieved. Interestingly, in our first case, even the right renal mass shrank in size in response to nivolumab treatment. As MRI revealed a tumour pseudocapsule, we suspected that the tumour was a low‐grade renal cell carcinoma. Nivolumab has also been confirmed as being effective against advanced renal clear cell carcinoma 6, which lent support to our suspicion that the renal mass was a renal clear cell carcinoma. In addition, the effects of nivolumab have lasted for very long, over two years. In our second case, while all other metastatic lesions continued to diminish in size in response to nivolumab treatment, the right adrenal gland mass became bulkier during the treatment. Several groups have reported mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors, including loss‐of‐function mutations in Janus kinases JAK1/2 7, an evolving landscape of mutations that encode tumour neoantigens recognizable by T cells 8, and the upregulation of alternative immune checkpoints in tumours 9; therefore, the adrenal mass progression in our case may have been due to these mechanisms of acquired resistance. The further evaluation of the antitumor efficacy/safety of anti‐PD‐1 antibody therapy in patients with NSCLC containing sarcomatoid components is warranted. While the long‐term clinical efficacy of anti‐PD‐1 antibody remains uncertain, our two cases serve to highlight the potential usefulness of anti‐PD‐1 antibody as an effective therapeutic agent for these tumours.

Disclosure Statements

Appropriate written informed consent was obtained for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Acknowledgement

Dr. S. Niho has received honoraria from Bristol‐Myers Squibb Co., and Dr. K. Goto has received grants and honoraria from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and honoraria from Bristol‐Myers Squibb Co.

Ota, T , Niho, S , Kirita, K , Ishii, G , Tsuboi, M , Goto, K . (2019) Impressive response to nivolumab of non‐small‐cell lung cancer containing sarcomatoid components. Respirology Case Reports, 7(8), e00477. 10.1002/rcr2.477

Associate Editor: Kazuhisa Takahashi

References

- 1. Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. 2015. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous‐cell non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 373(2):123–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kim S, Kim MY, Koh J, et al. 2015. Programmed death‐1 ligand 1 and 2 are highly expressed in pleomorphic carcinomas of the lung: comparison of sarcomatous and carcinomatous areas. Eur. J. Cancer 51(17):2698–2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ito K, Hataji O, Katsuta K, et al. 2016. "Pseudoprogression" of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma during nivolumab therapy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 11(10):e117–e119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yaguchi D, Ichikawa M, Ito M, et al. 2019. Dramatic response to nivolumab after local radiotherapy in pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma with rapid progressive post‐surgical recurrence. Thorac. Cancer 10(5):1263–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Senoo S, Ninomiya T, Makimoto G, et al. 2019. Rapid and long‐term response of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma to nivolumab. Intern. Med. 58(7):985–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. 2015. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal‐cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 373(19):1803–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zaretsky JM, Garcia‐Diaz A, Shin DS, et al. 2016. Mutations associated with acquired resistance to PD‐1 blockade in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 375(9):819–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anagnostou V, Smith KN, Forde PM, et al. 2017. Evolution of neoantigen landscape during immune checkpoint blockade in non‐small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 7(3):264–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koyama S, Akbay EA, Li YY, et al. 2016. Adaptive resistance to therapeutic PD‐1 blockade is associated with upregulation of alternative immune checkpoints. Nat. Commun. 7:10501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]