Abstract

Participation is a major outcome area for physical therapists serving young children with disabilities. Contemporary models of disability such as the International Classification of Function, developmental theories such as the system perspective, and evidence-based early childhood practices recognize the interdependence of developmental domains, and suggest that change in 1 area of development influences change in another. Physical therapy provided in naturally occurring activities and routines, considered the preferred service delivery method, promotes participation of young children with disabilities. Research indicates that: (1) children develop skills, become independent, and form relationships through participation; and (2) with developing skills, children can increasingly participate. The purpose of this Perspective article is to synthesize the literature examining the relationship between motor skill development and the social interaction dimension of participation in young children. Current research examining the influence of motor skill development on social interactions in children with autism spectrum disorder will be discussed, exemplifying the interdependence of developmental domains. Implications for physical therapist practice and recommendations for future research are provided.

The purpose of this Perspective article is to discuss the interrelationship between motor skill performance and participation by specifically addressing the social interaction component of participation for typically developing children and children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). First, we will define participation using definitions from the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: Children and Youth (ICF-CY),1 the pediatric physical therapy literature, and contemporary early childhood intervention practice. Second, we will discuss the literature on the interdependence of developmental domains and how it influences participation. Third, we will apply this to research regarding young children with ASD. Finally, we will offer clinical applications that promote participation by exploiting the motor–social-interaction link as well as recommendations for future research.

Multidimensionality of Participation

The neuromaturational theory of development guided most pediatric physical therapist interventions during the latter half of the 20th century.2 Treatment planning and intervention primarily focused on reducing impairments in body structures and function and activity limitations by inhibiting reflexes, promoting the developmental sequence, and facilitating developmental milestones.2 The work of contemporary researchers such as Thelen,3 Campos,4 Adolph,5 and Lockman6 provides evidence that development emerges from the complex interaction of physical and environmental factors and suggests that some achievements in developmental domains can impact growth in other domains, the theoretical construct of developmental cascades.3 Policy mandates, such as Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act,7 also influence what therapists emphasize during intervention as well as in treatment planning. Current intervention is grounded in the belief that development and learning are “dynamic, non-linear, and embedded within day-to-day experiences.”8 Best practice obligates pediatric physical therapists to create team-based, family-centered intervention plans assisting children and their families to reach outcomes that focus on participating in activities and routines that they are expected to do or would like to do, such as attending school, playing a team sport, or being a member of a community organization.

Critical to the ICF-CY model1 is the person's ability to participate in home, school, and community activities. The ICF-CY is derived from the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health9 to record the characteristics of the developing child and the influence of the surrounding environment. Building on the framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, the ICF-CY conceptualizes the impact of disability on body structures and function, activities, and participation as well as relevant personal and environmental factors during infancy, childhood, and adolescence. Thus, participation can be influenced by impairments in body structures and function, activity limitations, and environmental and personal factors. For example, children's physical abilities, health status, and emotional regulation can each impact their ability to physically and emotionally attend to and be involved in the situation.10,11

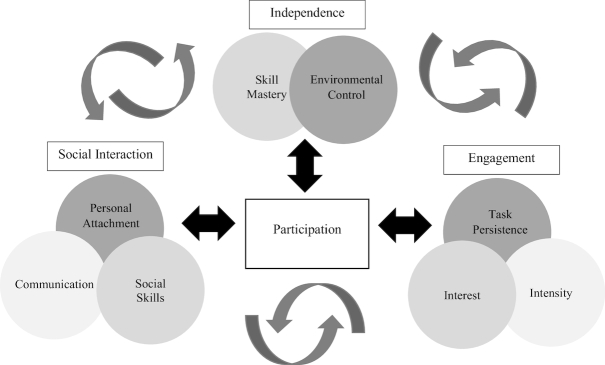

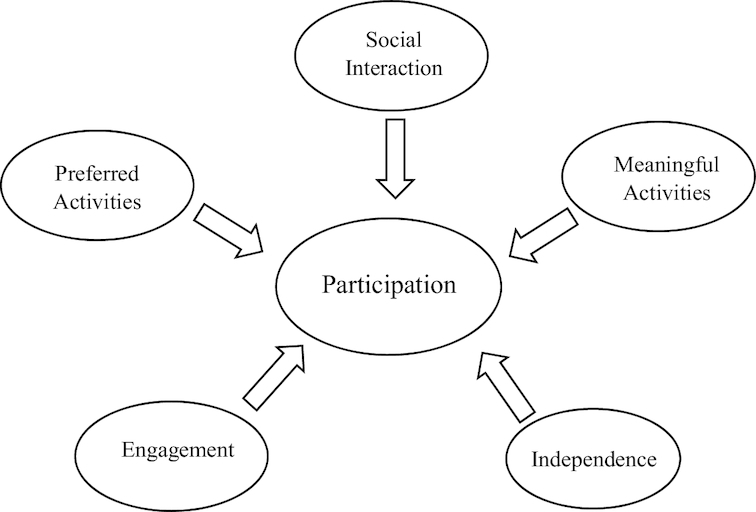

Although the importance of participation is generally agreed upon, definitions of participation in the literature have varied.12 The ICF-CY model defines participation as “involvement in life situations”1; however, this definition is vague and fails to capture the multidimensionality of participation. This has led to descriptions of participation in terms of the components that comprise it (Fig. 1). Carey and Long identified common themes in definitions of participation used in the literature, including carrying out activities with others, participating in social roles, congruity with personal priorities and goals, contributions to quality of life, and relevance to meaningful outcomes for the child and family.13 Following a systematic review of 25 studies, Imms et al12 identified preference, attendance and involvement, activity competence, and sense of self as key components to definitions of participation. Chiarello2 expanded on Imms’ perspective and added the importance of personally or socially meaningful involvement and personal satisfaction in activity competence. She also identified predictors of participation as child preferences, enjoyment, age, gender, motor and communication abilities, cognition, self-care, adaptive behaviors, associated health conditions, and body structures and functions.2 Similarly, Palisano et al14 defined optimal participation as individual, meaningful, and context-driven.

Figure 1.

Commonly cited components of participation. Participation is a multidimensional construct that includes independent performance and engagement in activities and routines that are preferred by and are meaningful for the person in the presence of and with others.

Specific to young children, McWilliam15 described 3 interactive dimensions of participation: engagement in the activity, independence in accomplishing the activity, and the social interaction that takes place during the activity. Engagement is demonstrated by the child's involvement in an activity, persistence or concentration to complete a task, or interest in people or materials.16,17 Independence is defined as mastery of skills to gain control over the child's own actions or environment.18 Social interaction includes caregiver and peer relations, interactive communication, attachment, and positive interactions.8,15 Although we recognize that comprehensive intervention for children with disabilities should also consider impairments of body structures and function and activity limitations, we focus on the relationship between motor development and the social interaction component of participation.

Defining participation in terms of engagement, independence, and social interaction offers an opportunity to focus on the complex interplay among domains and the context in which skills will be performed (Fig. 2). For example, children might be able to put on clothes, but unable to participate in a dressing routine because, in addition to donning pieces of clothing, they would need to be able to choose appropriate clothing and put it on in a time-efficient manner. Likewise, although children might be able to kick a ball, in order to participate in a game of kick ball with peers, they must also, for example, understand social rules of the game such as turn taking and sharing.

Figure 2.

Dimensions of participation. Interactions between components of participation demonstrate the complexity of defining participation for young children.

Although the developmental psychological community has long recognized the important link between motor development, especially locomotion, and the development of cognitive, social, and language skills,4 only recently have physical therapists and other service providers acknowledged perceptual-motor behaviors as a critical link to participation.19,20 For example, Lobo et al19 synthesized the growing body of literature on the influence on other areas of development of specific motor interventions provided to young children with disabilities. Based on the grounded cognition theory they reported on the correlation between delays in motor skill acquisition and other developmental areas, highlighting research on enhancing independent locomotion. Research has also shown that power mobility for children with a variety of disabilities has influenced the development of cognition, language, and social skills and has enhanced participation.20

In the following sections, we discuss the research supporting the interrelationship between motor skill performance and the social interaction dimension of participation for typically developing children and children with ASD. For the purpose of this article, social interaction includes social skills, social relationships, and social cognition.

Interdependence of Motor Skills and Social Interaction in Typical Development

The development of movement shows clear relationships with the development of communication, object exploration, and social interactions. Changes in posture allow children to: (1) sit up and manipulate objects they are familiar with in new ways; (2) move about their environment discovering new objects and situations to explore; and (3) communicate. These early experiences provide infants and young children with greater opportunity for interaction, physiological stability, social referencing, and contextual attributes, which all influence communication, language, and social and cognitive development.

Achievement of upright sitting postures allows the hands to be free for interaction with objects, to reach for objects, and to explore attributes of objects. Exploring objects allows infants to develop the concepts of object properties such as weight, texture, and size.6 Active exploration of objects and the environment also offers infants new learning opportunities. For example, infants who were offered opportunities to actively explore objects with the help of “sticky mittens” demonstrated increased visual preference for faces versus objects when compared with infants who were only able to passively explore objects.21

Also, as infants use rhythmical movements such as rattle shaking, the onset of babbling is seen,22,23 indicating that they use the rhythmic movements of the body to practice making movements with the mouth or reduplicated babbling.24 Like reduplicated babbling, rhythmic arm movements are organized and tightly timed actions. Thus, performing rhythmic arm movements such as hand banging provides a supportive context for the development of reduplicated babbling.24 Other research shows that motor and communication skills are highly correlated at 18 months of age and predictive of communication skills at 3 years of age,25 suggesting that motor skills can be foundational for communication development, which influences growth of social relationships and participation as explained by the theoretical construct of developmental cascades.26

In addition to exploring properties of objects, research has linked a child's ability to separate and construct objects to increases in vocabulary.24 During prespeech, children were more likely to interact with objects by pulling them apart prior to the development of speech, but as children learned to put things together, vocabulary increased, irrespective of chronological age.24 The physical action of manipulating objects creates a context for attaching meaning and understanding.

Along with freeing of hands, upright sitting also brings changes to the rib cage that allow for improved respiratory control needed for vocalizing and positioning of the lips, tongue, teeth, and pharynx for speech.24 Upright sitting allows for easier breathing to promote longer utterances and positions the tongue forward to enable production of consonant-vowel combinations.24

The development of independent sitting and object exploration enhances social development by providing new experiences to interact with caregivers. For example, upright posture enables the infant to gaze around the environment and begin to develop relational understanding.27 Likewise, the ability to sit independently and reach for objects can lead to opportunities to share objects with caregivers for a social experience28 and helps the infant develop relational play.29 Using these abilities, the infant is able to actively engage in daily routines in a new way.

The development of mobility also significantly increases social function and participation in toddlers. The onset of locomotion through crawling or walking increases opportunities for social interaction; however, the more advanced skill of walking offers greater opportunity for social interaction than crawling. Children who were walking at 12 months looked to an adult for social interaction (social bids) more frequently than 12-month-old infants who were crawling.30 Compared with infants who were walking at 12 months, infants who were crawling at the same age also spent a higher percentage of time passively watching others rather than interacting with them.30 Similarly, infants who were walking at 13 months were more likely to engage in social bids by bringing an object toward the mother to share attention whereas the crawlers were more likely to remain stationary while engaging in social interaction.28 The fact that the walkers were more likely than crawlers to move toward a person to engage in social interaction suggests that how infants engage in these exchanges differs and becomes more active as infants gain upright mobility. Thus, the transition from crawling to walking marks a shift from passive observation to increased social interaction with others in a child's environment.

Independent upright mobility can also be linked to more complex social communication. Compared with infants who were crawling at 12 months, infants who were walking at 12 months interacted with their mothers in addition to toys and used more directed gestures, indicating that the transition to independent walking influences participation by enabling more active exploration of the environment and increased social interactions and engagement with familiar adults.31 The child's ability to explore the environment also reinforces the concepts of space and time and reinforces the development of joint attention.4 With the development of spatial orientation, children understand the components of joint attention indicating that something is where the person is pointing rather than with them directly.4 Thus, when children are able to walk, their social interactions become more complex, more specific, and person directed.

Motor skills continue to influence the social interaction component of participation as children reach preschool and kindergarten. Children begin to interact with peers through active play that requires the use of more complex motor skills at these ages. Wilson et al32 found positive correlations between motor and social skills, indicating that children with more developed motor skills also displayed more developed social skills. They also found that a child's negative self-appraisals decreased with more advanced motor abilities. Other work indicates that ball skills, such as throwing, catching, and kicking, and visual motor skills, such as building with blocks, stringing beads, and tracing and copying, are related to social competence as well as executive function in preschoolers.33 Similarly, less frequent social interaction during play and a greater degree of shyness were observed in kindergartners with below-average motor abilities when compared with children of average or above-average motor abilities.34 Motor skills of children in kindergarten continue to correlate with social interaction and predict social-emotional adjustment and scholastic adaptation in first grade.35 Taken together, motor skills continue to provide a foundation for children to develop social relationships with peers, increasing opportunities for participation.

Although most research has focused on changes in the motor system and their potential impact on social development, it is important to note that the relationship between motor skill development and social interaction and its effect on participation can be bidirectional. Thelen posits that because developmental systems are interdependent, it is not possible to know which event causes another.3 It is possible that a young child could use social behaviors to reinforce interactions with caregivers, which could serve to increase opportunities for practice. For example, when infants smile, make eye contact, or begin to make vocalizations, caregivers could be encouraged to interact with them more, offering interactive opportunities to practice the motor skills. Likewise, preschool-aged and older children with more mature social skills than their peers could have more opportunities to practice motor skills through group play or activities, which also increases participation.

Interdependence of Motor Skills and Social Interaction in Children with ASD

Understanding these relationships in children with disabilities is important for pediatric physical therapists whose goal is to help children participate in daily routines and activities.2 The interrelationships between motor skills and the development of social interactions have been studied in children with primary motor disorders. For example, in children with developmental coordination disorder, degree of motor impairment has been linked to social status,36 social interaction,37 social isolation,38 and ability to form relationships.39 Likewise, motor development in children with cerebral palsy is predictive of social function,40 and movement and social ability have been identified as determinants of participation.41

In disorders in which motor impairment is not a defining feature, however, these relationships warrant exploration. Although ASD is considered primarily a social-communication and behavioral disorder, many children with ASD demonstrate delayed development of gross motor milestones, gait abnormalities, postural instability, and coordination deficits,42–44 thus inquiry into the role motor skills play in children with ASD is warranted. In this article we use ASD as a model disorder to demonstrate interrelationships between motor skill performance and the social interaction component of participation because it has not been examined previously in the literature and because of the potential importance to this population.

A body of literature exists to support the link between motor skills and other areas of development in children with ASD. For example, early motor delay in infants at risk for autism has been linked to later delays in expressive45,46 and receptive language.45 Infants at risk for ASD also explore objects differently than infants at low risk.47–49 When infants at risk for ASD interact with objects, they rely more on visual exploration47,48 and engage in purposeful dropping of objects less frequently than those at low risk.47 Additionally, infants at risk for autism tend to engage in less frequent object sharing when walking than infants at low risk.49

Specific components of motor skills have also been linked to social interaction in children with ASD. For example, static balance and ball skills predict social function in preschoolers with ASD50 and differentiate ASD from typical development51 or children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.52 Overall gross motor skills,53 and specifically ball skills,54,55 have also been used to predict ASD severity. As seen in typically developing children, these studies suggest that motor development provides a foundation for developing social skills and relationships in children with ASD.

The role that motor development plays in the social interaction component of participation for children with ASD is important to recognize. Highly restricted interests are a diagnostic criterion for ASD, and research has confirmed that children with the disorder have a limited range of preferred activities when compared with their peers, and often engage in these activities either alone or with family rather than with their peers.56 Parents confirm that their children with ASD have a high interest in sedentary activities, such as watching TV or playing video games, which impacts their ability to interact with other children.57 They also report, however, that developing social interaction and peer relationships is important.57,58 The limited repertoire of preferred and mastered motor skills can lead to fewer opportunities to develop social relationships, which leads to an overall decrease in participation.

Implications for Practice

The interdependence of developmental domains has several implications for physical therapy. First, if motor ability is linked to social interaction, it is possible that interventions that target motor skills or use movement could positively impact social development and improve participation. Studies in children with ASD have shown positive benefits to social development following motor-based interventions. Improvements in behavior and sensory processing as well as social communication have been observed following equine therapy programs.59 Reviews of exercise and physical activity interventions such as jogging, swimming, or yoga have demonstrated improvements in stereotypical behaviors,60–62 overall engagement,61,62 and social emotional function.60 A scoping review of “movement-based” interventions using role play or imitation also demonstrated positive findings in social function and joint attention.63 Likewise, a series of studies by Srinivasan and colleagues64–66 indicated that interventions using rhythmic movements and motor imitation can lead to positive changes in social attention and verbalization. Because difficulty with social communication and interaction is a hallmark of ASD, strategies that influence these areas positively are of the utmost importance. Pediatric physical therapists in collaboration with other disciplines should use the knowledge generated by research investigating the motor-social link in young children with ASD when designing outcomes as well as intervention activities.

Second, to develop interventions that capitalize on the link between motor and social development to promote participation, it is critical to gather information on aspects of participation in addition to body structure and function and activity limitations. Physical therapists should consider the use of participation measures as an integral part of the physical therapy examination. As discussed previously, participation includes engagement, social interaction, and independence; however, other definitions of participation also include preferences for activities, how often one has the opportunity to participate in preferred activities or with whom a child participates2,12,67 Tables 1 and 2 provide an overview of selected participation measures that pediatric physical therapists could incorporate into their examination and assessment strategies. These measures provide valuable information related to identified components of participation and should be routinely included in physical therapy examinations or as a component of comprehensive team-based evaluations.13 Therapists, in collaboration with the family and team members, can use this information to develop meaningful outcomes and goals and to measure change over time.2

Table 1.

Standardized Tools that Measure Participation in Young Children

| Name | Purpose | Age Range | Administration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)74 | Identifies activities children need to or would like to participate in and measures change in performance and satisfaction over time | All ages | Interview with child or parent |

| Children's Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) and Preferences for Activities of Children (PAC)67 | Examines diversity, intensity, enjoyment, and context of activities of children and preference for participation in activities | 6–21 y | Self-report questionnaire/interview |

| Miller Function and Participation Scales (M-FUN)69 | Participation checklists measure participation in activities at home and school | 2–8 y | Parent, teacher, and child questionnaires |

| Participation and Environment Measure—Children and Youth (PEM-CY)75 | Measures participation at home, school, and in the community, as well as environmental factors | 5–17 y | Parent-report questionnaire |

| School Function Assessment (SFA)76 | Measures participation, task supports, and performance of school-related tasks | Kindergarten sixth grade | Questionnaire completed by school professional who has observed child's performance in school |

| Preschool Activity Card Sort (PACS)77 | Measures participation in and level of assistance needed in 6 domains (self-care, community mobility, high-demand leisure, low-demand leisure, social interaction, domestic, education) | 3–5 y | Parent interview |

Table 2.

Routines-Based Participation Assessments

| Assessment Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| Measure of Engagement, Independence, Social Relationships in Routines (MEISR)78 | A variety of tools have been developed for children between birth and 5 y of age that measure the 3 dimensions of participation (engagement, independence, and social relations) across naturally occurring activities and routines that take place within home and early child-care centers. Administration is through parent, caregiver, and/or teacher interviews |

| Routines-Based Interview-Scale for Assessment of Family Enjoyment within Routines (RBI-SAFER)79 | |

| Scale for Teachers’ Assessment of Routines Engagement (STARE) (requires child observation)80 | |

| Scale for Assessment of Teachers' Impressions of Routines Engagement (SATIRE) (focus on meeting classroom expectations)81 |

Third, participation measures can also be used to determine appropriate interventions for children with ASD. For example, measures that help identify the child's preferences, an important consideration for participation,2,12 can provide information on planning intervention activities or materials that engage the child. They can also be used to identify areas of participation, such as leisure or daily activities. Measures such as the Routines Based Assessments (Tab. 2) can indicate that the level of engagement of children within an activity is limiting their participation or not meeting expectations of the family or child-care provider rather than skill performance. The additional information provided from these tools can lead the therapist to modify, adapt, or accommodate activities in a way that increases engagement and in turn promotes successful participation.

The needs of children with disabilities are complex. Contemporary intervention supports an approach in which all team members collaborate to create and implement comprehensive, integrated intervention plans. Collaboration among team members is necessary for achievement of participation-based goals. Application of research on interdependence of developmental domains indicates that skills are not learned or practiced separate from other domains and suggests therapists should think more broadly about the impact of their intervention as well as the components of their intervention. Teams that focus on an integrated set of child- and/or family-directed outcomes targeting participation can prove more successful than the traditional discipline- or domain-specific goal approach.

Recommendations for Future Research

The interdependence between developmental domains is also an important line of inquiry in research. Researchers should include measures of participation as outcomes in future studies exploring benefits of motor interventions for children with disabilities. Participation-based assessment measures provide information regarding a child's behavior within a context, a principle that is fundamental to early childhood intervention and motor learning. Identifying changes in participation is also critical in support of family-centered care because parents consistently report that participation research is a high priority for them.68 The measures listed in Tables 1 and 2 can also be used in research. These general tools are appropriate for children with a variety of disabilities, although some research has identified usefulness in specific populations. For example, the motor performance scales and the home participation checklists of the Miller Function and Participation Scales69 have been used with children with ASD and could be an option for research looking at participation and motor skills.50,70

A systematic review by Adair et al71 found only 7 randomized controlled trials measuring participation as an outcome for interventions in children with disabilities. Moreover, only a few of them presented findings that interventions impacted participation. Adair et al suggest that researchers should consider including measures of the specific components of participation they hope to change, rather than relying on comprehensive scales. Inclusion of measures such as those listed in the tables will provide information on engagement, independence, and social interactions, among other dimensions, and would also help researchers to determine the impact of motor-skill intervention on domains beyond motor skills.

Research examining participation in community-based programs is also needed. Providing motor interventions to children with ASD alongside typically developing peers in community-based programs has been shown to improve social skills in children with ASD. Morrier and Ziegler72 reported increased social interaction skills in a group of children with ASD following an intervention in which the children with ASD were paired with typically developing peers during structured recess activities. Casey et al73 reported positive improvements in socialization using a phased approach in which children with ASD were taught specific skills necessary for ice skating and then later practiced those skills in an inclusive setting with typically developing peers. Including typically developing peers in intervention groups to serve as peer role models can be helpful for children with disabilities and warrants further exploration.

Researchers should also consider creative solutions to combat the challenges to research design that are common in rehabilitation research. Four of the 5 articles we found that reviewed the impact of motor interventions on social function identified methodological concerns, including small heterogeneous samples59–62 and lack of comparison groups.59,62 Stronger designs including control or comparison groups as well as increased sample sizes are needed in order to draw definitive conclusions about the efficacy of our research.

Conclusion

The ICF-CY model emphasizes participation as a major area of concern for children with disabilities. Optimal participation14 includes the attributes of the child, family, and environment and the dimensions of participation described in this article. Evidence suggests that changes in the way children move and interact with their environment and with others promote optimal participation. Interventions that capitalize on the interrelationship between developmental domains could be a promising way to improve developmental outcomes for children. Although the demonstrated improvements that mobility and motor-skill interventions have yielded in the social interaction component of participation in children with disabilities are encouraging, more work needs to be done to fully delineate the role motor skills play in this area. Given the current emphasis on participation and the role of context, research exploring the interdependence of motor skills with other developmental domains is warranted.

Contributor Information

Jamie M Holloway, University of South Florida, School of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Sciences, 12901 Bruce B. Downs Blvd, MDC 077, Tampa, FL 33612 (USA).

Toby M Long, Georgetown University, Center for Child and Human Development, Washington, District of Columbia.

Author Contributions

Concept/idea/research design: J.M. Holloway, T.M. Long

Writing: J.M. Holloway, T.M. Long

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): J.M. Holloway

Funding

There is no funding to report related to this article.

Disclosures

The authors completed the ICJME Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: Children and Youth Version. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chiarello LA. Excellence in promoting participation: striving for the 10 Cs—client-centered care, consideration of complexity, collaboration, coaching, capacity building, contextualization, creativity, community, curricular changes, and curiosity. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2017;29:S16–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thelen E. Dynamic systems theory and the complexity of change. Psychoanal Dialogues. 2005;15:255–283. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Campos JJ, Anderson DI, Barbu-Roth MA, Hubbard EM, Hertenstein MJ, Witherington D. Travel broadens the mind. Infancy. 2000;1:149–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adolph K. Learning to learn in the development of action. In: Lockman J, Reiser J, Nelson CA, eds. Action as an Organizer of Perception and Cognition During Learning and Development: Minnesota Symposium on Child Development. Vol 33. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Press; 2005: 91–122. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lockman JJ, Kahrs BA. New insights into the development of human tool use. Current Dir Psychol Sci. 2017;26:330–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Public Law 108-446, Individuals With Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004. Available at https://sites.ed.gov/idea/statuteregulations/. Accessed March 28, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Logan SW, Ross SM, Schreiber MAet al. Why we move: social mobility behaviors of non-disabled and disabled children across childcare contexts. Front Public Health. 2016;4:204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Askari S, Anaby D, Bergthorson M, Majnemer A, Elsabbagh M, Zwaigenbaum L. Participation of children and youth with autism spectrum disorder: a scoping review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;2:103–114. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Imms C, Reilly S, Carlin J, Dodd KJ. Characteristics influencing participation of Australian children with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:2204–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Imms C, Adair B, Keen D, Ullenhag A, Rosenbaum P, Granlund M. ‘Participation’: a systematic review of language, definitions, and constructs used in intervention research with children with disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carey H, Long T. The pediatric physical therapist's role in promoting and measuring participation in children with disabilities. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2012;24:163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Palisano RJ, Chiarello LA, King GA, Novak I, Stoner T, Fiss A. Participation-based therapy for children with physical disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:1041–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McWilliam RA. Routines-Based Early Intervention. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16. McWilliam RA, Bailey DB. Promoting engagement and mastery. In: Bailey DB, Wolery M, eds. Teaching Infants and Preschoolers with Disabilities. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McMillan Publishing Company; 1992: 230–255. [Google Scholar]

- 17. ECTACenter. Child engagement: An important factor in child learning. http://ptan.seresc.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/ChildEngagement.docx. Accessed January 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Davis E, Reddihough D, Murphy Net al. Exploring quality of life of children with cerebral palsy and intellectual disability: what are the important domains of life? Child Care Health Dev. 2017;43:854–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lobo MA, Harbourne RT, Dusing SC, McCoy SW. Grounding early intervention: physical therapy cannot just be about motor skills anymore. Phys Ther. 2013;93:94–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Feldner HA, Logan SW, Galloway JC. Why the time is right for a radical paradigm shift in early powered mobility: the role of powered mobility technology devices, policy and stakeholders. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2016;11:89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Libertus K, Needham A. Reaching experience increases face preference in 3-month-old infants. Dev Sci. 2011;14:1355–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ejiri K. Relationship between rhythmic behavior and canonical babbling in infant vocal development. Phonetica. 1998;55:226–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Iverson JM, Hall AJ, Nickel L, Wozniak RH. The relationship between reduplicated babble onset and laterality biases in infant rhythmic arm movements. Brain Lang. 2007;101:198–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iverson JM. Developing language in a developing body: the relationship between motor development and language development. J Child Lang. 2010;37:229–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang MV, Lekhal R, Aaro LE, Schjolberg S. Co-occurring development of early childhood communication and motor skills: results from a population-based longitudinal study. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Karasik L, Tamis-Lemonda C, Adolph K. Crawling and walking infants elicit different verbal responses from mothers. Dev Sci. 2014;17:388–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fogel A, Messinger DS, Dickson KL, Hsu H-C. Posture and gaze in early mother-infant communication: synchronization of developmental trajectories. Dev Sci. 1999;2:325–332. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Karasik LB, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Adolph KE. Transition from crawling to walking and infants' actions with objects and people. Child Dev. 2011;82:1199–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bakeman R, Adamson LB, Konner M, Barr RG. Kung infancy: the social context of object exploration. Child Dev. 1990;61:794–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clearfield MW, Osborne CN, Mullen M. Learning by looking: Infants' social looking behavior across the transition from crawling to walking. J Exp Child Psychol. 2008;100:297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Clearfield MW. Learning to walk changes infants' social interactions. Infant Behav Dev. 2011;34:15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wilson A, Piek JP, Kane R. The mediating role of social skills in the relationship between motor ability and internalizing symptoms in pre‐primary children. Infant Child Dev. 2013;22:151–164. [Google Scholar]

- 33. MacDonald M, Lipscomb S, McClelland MMet al. Relations of preschoolers' visual-motor and object manipulation skills with executive function and social behavior. Res Q Exer Sport. 2016;87:396–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bar-Haim Y, Bart O. Motor function and social participation in kindergarten children. Soc Dev. 2006;15:296–310. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bart O, Hajami D, Bar-Haim Y. Predicting school adjustment from motor abilities in kindergarten. Infant Child Dev. 2007;16:597–615. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kanioglou A, Tsorbatzoudis H, Barkoukis V. Socialization and behavioral problems of elementary school pupils with developmental coordination disorder. Percept Mot Skills. 2005;101:163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kennedy-Behr A, Rodger S, Mickan S. Physical and social play of preschool children with and without coordination difficulties: preliminary findings. Br J Occup Ther. 2011;74:348–354. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jarus T, Lourie-Gelberg Y, Engel-Yeger B, Bart O. Participation patterns of school-aged children with and without DCD. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:1323–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schoemaker MM, Kalverboer AF. Social and affective problems of children who are clumsy: how early do they begin? Adapt Phys Activ Q. 1994;11:130–140. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Whittingham K, Fahey M, Rawicki B, Boyd R. The relationships between motor abilities and early social development in a preschool cohort of children with cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil. 2010;31:1346–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.</number> Chiarello LA, Palisano RJ, Bartlett DJ, McCoy SW. A multivariate model of determinants of change in gross-motor abilities and engagement in self-care and play of young children with cerebral palsy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2011;31:150–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bhat AN, Landa RJ, Galloway JC. Current perspectives on motor functioning in infants, children, and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Phys Ther. 2011;91:1116–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mieres AC, Kirby RS, Armstrong KH, Murphy TK, Grossman L. Autism spectrum disorder: an emerging opportunity for physical therapy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2012;24:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kaur M, Srinivasan SM, Bhat AN. Comparing motor performance, praxis, coordination, and interpersonal synchrony between children with and without autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Res Dev Disabil. 2018;72:79–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bedford R, Pickles A, Lord C. Early gross motor skills predict the subsequent development of language in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2016;9:993–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Leonard HC, Bedford R, Pickles A, Hill EL. Predicting the rate of language development from early motor skills in at-risk infants who develop autism spectrum disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2015;13–14:15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kaur M, Srinivasan SM, Bhat AN. Atypical object exploration in infants at-risk for autism during the first year of lifer. Front Psychol. 2015;6:798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Koterba EA, Leezenbaum NB, Iverson JM. Object exploration at 6 and 9 months in infants with and without risk for autism. Autism. 2014;18:97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Srinivasan SM, Bhat AN. Differences in object sharing between infants at risk for autism and typically developing infants from 9 to 15 months of age. Infant Behav Dev. 2016;42:128–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Holloway JM, Long TM, Biasini F. Relationships between gross motor skills and social function in young boys with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2018;30:184–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Whyatt CP, Craig CM. Motor skills in children aged 7–10 years, diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:1799–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ament K, Mejia A, Buhlman Ret al. Evidence for specificity of motor impairments in catching and balance in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:742–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. MacDonald M, Lord C, Ulrich D. Motor skills and calibrated autism severity in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Adapt Phys Activ Q. 2014;31:95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. MacDonald M, Lord C, Ulrich D. The relationship of motor skills and social communicative skills in school-aged children with autism spectrum disorder. Adapt Phys Activ Q. 2013;30:271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Craig F, Lorenzo A, Lucarelli E, Russo L, Fanizza I, Trabacca A. Motor competency and social communication skills in preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2018;11:893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Potvin MC, Snider L, Prelock P, Kehayia E, Wood-Dauphinee S. Recreational participation of children with high functioning autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43:445–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Simpson K, Keen D, Adams D, Alston-Knox C, Roberts J. Participation of children on the autism spectrum in home, school, and community. Child Care Health Dev. 2018;44:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Germani T, Zwaigenbaum L, Magill-Evans J, Hodgetts S, Ball G. Stakeholders' perspectives on social participation in preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. Dev Neurorehabil. 2017;20:475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Srinivasan SM, Cavagnino DT, Bhat AN. Effects of equine therapy on individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;5:156–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bremer E, Crozier M, Lloyd M. A systematic review of the behavioural outcomes following exercise interventions for children and youth with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2016;20:899–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sowa M, Meulenbroek R. Effects of physical exercise on autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2012;6:46–57. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Srinivasan SM, Pescatello LS, Bhat AN. Current perspectives on physical activity and exercise recommendations for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Phys Ther. 2014;94:875–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lee K, Lambert H, Wittich W, Kehayia E, Park M. The use of movement-based interventions with children diagnosed with autism for psychosocial outcomes a scoping review. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2016;24:53–67. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Srinivasan S, Bhat A. The effect of robot-child interactions on social attention and verbalization patterns of typically developing children and children with autism between 4 and 8 years. Autism Open Access. 2013;3:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Srinivasan SM, Eigsti I-M, Gifford T, Bhat AN. The effects of embodied rhythm and robotic interventions on the spontaneous and responsive verbal communication skills of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): a further outcome of a pilot randomized controlled trial. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2016;27:73–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Srinivasan SM, Eigsti I-M, Neelly L, Bhat AN. The effects of embodied rhythm and robotic interventions on the spontaneous and responsive social attention patterns of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): a pilot randomized controlled trial. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2016;27:54–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. King G, Law M, King Set al. Children's Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment and Preferences for Activities of Children. San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 68. McIntyre S, Novak I, Cusick A. Consensus research priorities for cerebral palsy: a Delphi survey of consumers, researchers, and clinicians. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:270–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Miller L. Miller Function and Participation Scales. San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Holloway JM, Long T, Biasini F. Concurrent validity of two standardized measures of gross motor function in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2019;39:193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Adair B, Ullenhag A, Keen D, Granlund M, Imms C. The effect of interventions aimed at improving participation outcomes for children with disabilities: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57:1093–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Morrier M, Ziegler S. I wanna play too: factors related to changes in social behavior for children with and without autism spectrum disorder after implementation of a structured outdoor play curriculum. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48:2530–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Casey AF, Quenneville-Himbeault G, Normore A, Davis H, Martell SG. A therapeutic skating intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2015;27:170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Law M, Baptiste S, Carswell A, McColl M, Polatajiko H, Polluck N. Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. 5th ed. Ottawa: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Coster W, Law M, Bedell G, Khetani M, Cousins M, Teplicky R. Development of the participation and environment measure for children and youth: conceptual basis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Coster W, Deeney T, Haltiwanger J, Haley S. School Function Assessment. San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Berg C, LaVesser P. The preschool activity card sort. OTJR Occup Part Heal. 2006;26:143–151. [Google Scholar]

- 78. McWilliam RA, Younggren N. Measure of Engagement, Independence, Social Relationships in Routines. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing; (in press). [Google Scholar]

- 79. Scott S, McWilliam RA. Routines-based interview-Scale for assessment of family enjoyment within routines. In: McWilliam RA, ed. Working with Families of Young Children with Special Needs. New York: Guilford Press; 2010: Appendix 2.3 pg 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Casey AM, McWilliam RA. The STARE: The scale for teachers' assessment of routines engagement. Young Exceptional Children. 2007;11:2–15. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Clingenpeel B, McWilliam R. Scale for the Assessment of Teachers’ Impressions of Routines and Engagement. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Medical Center; 2003. [Google Scholar]