Abstract

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) and VF account for the majority of sudden cardiac deaths worldwide. Treatments for VT/VF include anti-arrhythmic drugs, ICDs and catheter ablation, but these treatments vary in effectiveness and carry substantial risks and/or expense. Current methods of selecting patients for ICD implantation are imprecise and fail to identify some at-risk patients, while leading to others being overtreated. In this article, the authors discuss the current role and future direction of cardiac MRI (CMRI) in refining diagnosis and personalising ventricular arrhythmia management. The capability of CMRI with gadolinium contrast delayed-enhancement patterns and, more recently, T1 mapping to determine the aetiology of patients presenting with heart failure is well established. Although CMRI imaging in patients with ICDs can be challenging, recent technical developments have started to overcome this. CMRI can contribute to risk stratification, with precise and reproducible assessment of ejection fraction, quantification of scar and ‘border zone’ volumes, and other indices. Detailed tissue characterisation has begun to enable creation of personalised computer models to predict an individual patient’s arrhythmia risk. When patients require VT ablation, a substrate-based approach is frequently employed as haemodynamic instability may limit electrophysiological activation mapping. Beyond accurate localisation of substrate, CMRI could be used to predict the location of re-entrant circuits within the scar to guide ablation.

Keywords: Cardiac MRI, risk stratification, cardiomyopathy, ventricular tachycardia ablation

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) and VF occur mainly in people with impaired cardiac function and/or ischaemic heart disease, and account for the majority of sudden cardiac deaths worldwide.[1] Treatment with anti-arrhythmic drugs such as amiodarone may be at best neutral in terms of mortality and carries significant long-term risks.[2,3] While ICDs significantly improve survival for patients with significantly impaired left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), the devices also carry risks of infection and inappropriate shocks being given.[4,5]

Some patients may present with a ‘secondary prevention’ ICD indication such as sustained VT or VF arrest, but, in the primary prevention setting, the risk of arrhythmia is based on the presence and severity of structural heart disease. Selection of patients in this way lacks precision and fails to identify some at-risk patients while leading to overtreatment in others. Current guidelines recommend echocardiography as the first-line investigation for cardiac function due to ease of access, because the echocardiographic equipment is usually available in heart clinics, whereas cardiac MRI (CMRI) services currently tend to only be available in specialist (tertiary) centres.[6] However, CMRI is superior in terms of both accuracy and reproducibility when quantifying LVEF and myocardial mass, and can overcome limitations of inadequate echocardiographic windows. CMRI offers a one-stop investigation for accurately establishing cardiac structure, function and myocardial tissue characterisation.

Understanding the Substrate for Ventricular Arrhythmia

Ischaemic Cardiomyopathy

Studies of cardiac tissue obtained before transplantation or following left ventricular (LV) aneurysm surgery, as well as more recent human and animal CMRI studies, have confirmed our understanding of the structural changes that occur in ischaemic cardiomyopathy (ICM). Strands of surviving tissue within and at the periphery of the infarct region form tortuous and slowly-conducting channels which support re-entry, so the infarct border zone frequently has a heterogeneous appearance on CMRI.[8–10]

Fenoglio et al. demonstrated there were bundles of surviving myocytes in endocardial resection samples; some of these had a diameter of <100 µm, but it was not known which of these channels were mechanistically important.[11] De Bakker et al. showed that differential slow conduction occurs with multiple tracts <200 µm.[9] Recently, ultra-high (submillimetre) resolution ex vivo CMRI of infarcted porcine hearts showed conducting pathways were mainly subendocardial.[12] However, in this study, a significant minority of pathways were observed to be entirely epicardial and would be inaccessible for endocardial catheter ablation.

Urgent reperfusion (by either thrombolysis or angioplasty) for MI reduces infarct size and the incidence of subsequent chronic VT. In observational studies, VT cycle lengths were shorter, possibly suggesting a smaller circuit, in patients who had received revascularisation than in those who had not been revascularised.[13–15] This would suggest that reperfusion strategies can introduce greater substrate heterogeneity within the infarcted area.

Techniques that characterise and quantify the scar border zone or identify channels could improve risk stratification and treatment planning. However, while larger conducting channels may be identified using CMRI, it is likely that others are missed because of the limited spatial resolution of current clinical imaging. Where channels are too small to be visualised, measures of tissue heterogeneity may act as surrogates for the presence of ‘sub-resolution’ channels.

Non-ischaemic Cardiomyopathy

The aetiology of VT in patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy (NICM) is less well understood, partly because of the heterogeneity of underlying pathological processes in NICM. When regional fibrosis is detectable, it is often midwall or subepicardial, making access for catheter ablation challenging. These factors may explain why outcomes from NICM VT ablation are worse than those in ischaemic cardiomyopathy.[16]

In contrast to macro re-entrant VT, polymorphic VT or VF may occur due to distinct (but related) mechanisms. Replacement fibrosis can be patchy and/or diffuse, with disruption of the left ventricular microarchitecture.[17] This diffuse fibrosis provides the substrate for conduction block and micro re-entry resulting in VF.[18,19] This substrate is often dynamic with progressive fibrosis, reducing the long-term efficacy of targeted substrate modification.

Cardiac MRI Tissue Characterisation

Late Gadolinium Enhancement

Late gadolinium enhanced (LGE) CMRI imaging has become the de facto standard for imaging myocardial fibrosis. This approach uses gadolinium as a contrast agent to highlight areas of heterogeneity within the myocardium (e.g. fibrotic versus normal areas). In normal tissue, the washout of gadolinium is rapid, whereas in areas of myocardial fibrosis the washout is slower. By timing the image acquisition to occur ‘late’ when washout has occurred in normal tissue but not in fibrotic tissue, regions of normal and fibrosed tissue can be differentiated. This technique relies on setting the inversion time to ‘null’ distant normal myocardium, making it appear black. Areas of enhancement have been demonstrated to correlate well with both acute myocardial necrosis and chronic fibrosis in ischaemic pathological specimens as well as replacement fibrosis in non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy.[20,21] Typical image resolution is 1.4 x 1.4 x 10 mm (the 10 mm distance is the gap between slices).

Quantification of Late Gadolinium Enhancement

Although a narrative report of scar distribution is typically given in clinical use, the volume of abnormal tissue can also be quantified based on signal intensity (SI). Manual planimetry requires the operator to manually identify areas of fibrosis, whereas semi-automated standard deviation (SD) or full width at half maximum (FWHM) techniques require less user input. The SD method defines abnormal voxels with more than 2, 3, 4, 5 or 6 standard deviations greater than the SI in a user-defined region of ‘normal’ myocardium. The FWHM method identifies tissues that fall below the SI of a user-defined area of fibrosis. Typical FWHM thresholds define a dense scar as one with >50% peak SI and a border zone between 35% and 50%.[22–24] These techniques generate either a mass or percentage value of affected myocardium for the total scar burden, or for subdivisions of border zone and scar core. Although these techniques are reproducible, depending on the method and threshold chosen, significant inter-method variation is seen, and there is limited comparison with the gold standard of pathological specimens.[25] In a small series, FWHM method correlates best with pathological specimens in animals and with manual segmentation in humans with ICM.[24,26]

T1 Mapping

Conditions with diffuse tissue fibrosis are more challenging to detect with LGE if there are no unaffected myocardial segments. Measurement of absolute T1 relaxation values sidesteps the requirement for tissue inhomogeneity in LGE imaging. Spatial resolution is inferior to LGE imaging at approximately 1.4 x 1.9 x 6 mm and is challenging at higher heart rates, though native T1 mapping does not require the use of a contrast agent.[27] As imaging protocols, field strength and acquisition methods vary, reference T1 values are specific to the vendor/manufacturer.

Unlike LGE, native T1 values are frequently abnormal in diffuse diseases of the myocardium, giving insights into the aetiology of NICM. T1 values are increased by tissue oedema and fibrosis, and are reduced by lipid overload (e.g. in Anderson-Fabry disease) and iron overload.[28] For clinical use, mid-myocardial septal values for T1 are reported, though a map can be generated showing the native T1 values across an imaging slice. The T1 map may highlight focal areas of oedema as seen in acute myocarditis, acute myocardial infarction or takotsubo cardiomyopathy.[29,30]

Extracellular Volume

Contrast-enhanced T1 mapping allows the extracellular volume (ECV) to be estimated. By comparing pre- and post-contrast T1 values (referencing the T1 values of the blood pool and the patient’s haematocrit), a value for ECV is obtained. This is expressed as a fraction of the tissue volume; published normal values for ECV are approximately 25%.[31,32] While native T1 values examine entire tissues, ECV characterises only the extracellular matrix and is therefore less affected by acute oedema. Higher ECV values are seen with expansion of the interstitium due to fibrosis or deposition and therefore correlate well with fibrotic changes at endomyocardial biopsy.[33,34]

As with native T1, ECV can be expressed as a global value or as a map highlighting regional variation. While ECV is raised in areas of chronic infarction, its main advantage over LGE for arrhythmic risk stratification is its potential to identify diffuse myocardial fibrosis in NICM.[28,35]

T2 Imaging

Acute myocardial injury results in interstitial oedema. This occurs rapidly after myocardial infarction, and T2-weighted CMRI sequences, which identify oedema, can predict final infarct size.[36] In chronic conditions such as cardiac sarcoidosis, myocarditis, transplant rejection and toxic cardiomyopathies, T2-weighted imaging accurately identifies myocardial oedema.[37] While arrhythmic complications in these conditions may be predicted using CMRI, there is limited data to support T2 imaging for arrhythmic risk stratification in patients with ICM or NICM.[38]

Comparison of Techniques

LGE CMRI identifies the aetiology of left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD), and permits the identification and quantification of myocardial fibrosis. As a semi-quantitative technique, LGE can demonstrate only relative differences between fibrotic and non-fibrotic myocardium. As a result, diffuse diseases of the myocardium may be missed with this technique. Newer techniques such as T1 and ECV mapping have the advantage of being quantitative and, as such, can be used to identify such diffuse myocardial fibrosis seen in some forms of NICM. Table 1 demonstrates these differences. Examples of these techniques are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Table 1: Comparison of Myocardial Tissue Characterisation Techniques.

| Measurement | Scar identification/quantification | Scar density estimation | Quantification of scar border zone | Identification of diffuse fibrosis | Evidence for use as a decision aid for risk stratification | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late gadolinium enhancement | Semi-quantitative | +++ | - | ++ | - | ++ (ICM) +++ (NICM) |

| T1 mapping | Quantitative | + | + | - | + | + |

| Extracellular volume mapping | Quantitative | ++ | +++ | + | +++ | +/- |

ICM = ischaemic cardiomyopathy; NICM = non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy.

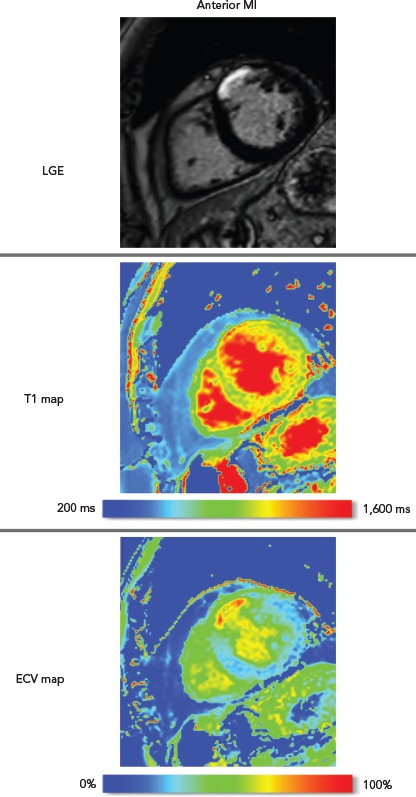

Figure 1: Ischaemic Cardiomyopathy: Image Comparison.

Ischaemic cardiomyopathy secondary to an anterior ST-elevation MI. In this short axis slice, there is subendocardial LGE in the left ventricular anterior wall. T1 native values are elevated in the same region. ECV demonstrates this is a dense scar (ECV >55%). ECV = extracellular volume; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement.

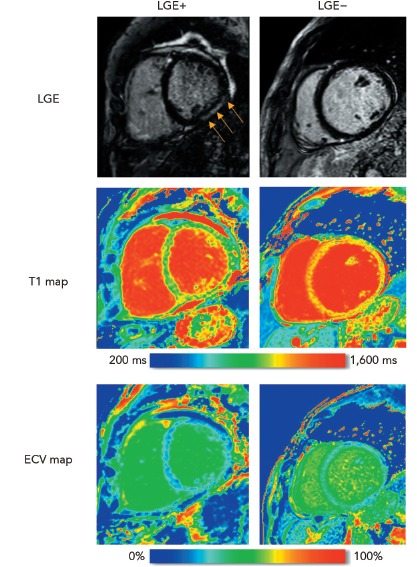

Figure 2: Non-ischaemic Cardiomyopathy: Image Comparison.

These two cases of non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy highlighting the utility of LGE, T1 and ECV. LGE+ is a case with mid-myocardial fibrosis (orange arrows), with globally high ECV. LGE- did not demonstrate any fibrosis on LGE imaging but had high native T1 and globally raised ECV, confirming the diagnosis of non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy. ECV = extracellular volume; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement.

Current Clinical Application of Cardiac MRI

Current guidelines recommend echocardiography as the firstline investigation in patients presenting with heart failure or VT, although CMRI gains a class I recommendation if an infiltrative cause is suspected.[39,40] With echocardiography or CMRI, regional wall motion abnormalities and wall thinning suggest an ischaemic aetiology, while global hypokinesis supports a non-ischaemic cause. However, assessment is highly dependent on image quality and CMRI can overcome inadequate echocardiographic windows.[39] In patients presenting with VT, CMRI is particularly useful for identifying inflammatory or infiltrative aetiology as well as ischaemic and non-ischaemic cardiomyopathies. In one series, CMRI changed the working diagnosis in 50% of patients presenting with VT/VF.[41] Myocardial infarction shows a subendocardial to full thickness pattern of LGE, which will conform to one or more coronary territories. Conversely, non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy often has a more diffuse pattern of fibrosis.[17] As a result, the location of regions highlighted by LGE in such patients is variable, but it is more commonly located in the midwall or epicardial regions of anteroseptal or inferolateral segments.[42]

Revascularisation of hypokinetic non-infarcted chronically ischaemic tissues may result in functional recovery.[43] Hyperenhancement transmurality in LGE CMRI correlates well with myocardial recovery after revascularisation. In a series of 50 patients, regions with ≤25% transmurality were likely to demonstrate improved contractility, while those with >50% transmurality showed poor functional recovery after revascularisation.[20]

When myocardial ischaemia causes polymorphic VT/VF, revascularisation is indicated. However, in patients with sustained monomorphic VT, revascularisation is more contentious, since monomorphic VT usually reflects established substrate that may not be altered by revascularisation. Indeed, in a case series of 65 patients with coronary disease and VT/VF, surgical revascularisation did not appear to affect inducibility of arrhythmia, but was associated with good long-term outcomes.[44] Several other observational studies have similarly found that a reduction in mortality is associated with either PCI or surgical revascularisation in patients presenting with VT/VF.[45–49]

Cardiac MRI Risk Stratification

Current European Society of Cardiology guidelines for ICD implantation (in both ICM and NICM) are based upon LVEF and New York Heart Association class but not formal scar quantification.[6] The more recent 2017 American Heart Association guidelines differ slightly, with a class IIa recommendation given for the use of CMRI imaging to aid risk stratification in patients with suspected NICM.[40]

To investigate the role of CMRI as a tool for risk stratification, PubMed was searched using the terms (‘Risk Assessment’[Mesh] OR ‘Prognosis’[Mesh] OR ‘Predictive Value of Tests’[Mesh]) AND (‘Myocardial Ischemia’[Mesh] OR ‘Dilated Cardiomyopathy’[Mesh]) AND (‘Magnetic Resonance Imaging’[Mesh]) OR ‘Gadolinium’[Mesh]) to identify studies using CMRI to guide risk stratification. These studies are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: Prognostic Impact of Cardiac MRI.

| Author | n | Method for Scar Quantification | HR for Adverse Outcome (95% CI) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischaemic Cardiomyopathy | ||||

| Bello et al. 2005[54] | 48 | ≥2 SD above remote normal myocardium | Not given, p=0.02 | Greater infarct mass and infarct surface area predicts inducible VT at EPS |

| Yan et al. 2006[58] | 144 | ≥2 SD above remote normal myocardium | 1.45 (1.15–1.84) per 10% increase in scar border zone | Extent of the peri-infarct zone defined by delayed-enhancement CMRI is an independent predictor of post-myocardial infarction all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, after adjusting for LV volumes or LVEF |

| Schmidt et al. 2007[119] | 47 | FWHM | Not given, p=0.02 | Border zone mass was higher in those with inducible VT than those with no inducibility, but there was no difference in scar core mass |

| Roes et al. 2009[120] | 91 | FWHM (35-50%) | 1.49 1.01–2.20) per 10 g increase in scar border zone. | Extent of infarct border zone is the strongest predictor of subsequent ICD therapy |

| Kwon et al. 2009[50] | 349 | ≥2 SDs above remote normal myocardium | 1.02 (1.003–1.03) per 1% increase in LV scar | Scar mass predicts mortality or transplantation |

| Kelle et al. 2009[121] | 177 | Number of AHA 17 segment model with enhancement | 1.27 (1.064–1.518) per additional enhanced segment | Number of AHA segments involved predicts death and non-fatal myocardial infarction. |

| Heidary et al. 2010[57] | 70 | FWHM border zone (remote max to 50%), FWHM scar core (>50%) | Not given, p=0.03 | Total scar mass and border zone mass (but not scar core mass) predict adverse outcomes |

| Scott et al. 2011[53] | 64 | The number of transmural scar segments (using AHA 17 segment model) | 1.48 (1.18–1.84) in multivariate analysis | The number of transmural scar segments predicts subsequent ICD therapies |

| Krittayaphong et al. 2011[122] | 1,148 | Visual presence of LGE | 3.92 (1.98–7.76) in multivariate analysis | LGE predicts MACE in a cohort with normal wall motion. |

| Boyé et al. 2011[123] | 52 | ≥5 SD | Not given, p=0.02 | Infarct mass expressed as a percentage of LV mass predicts appropriate device therapy |

| Rubenstein et al. 2013[59] | 47 | Between 2 and 3 SD above remote normal myocardium | 1.97 (1.04–3.73) per 1% change in border zone mass in multivariate analysis | Border zone mass higher in those with VT inducibility (2.64% of LV mass) than those without (1.35%) |

| Alexandre et al. 2013[124] | 49 | Scar mass by manual planimetry | 1.08 (1.04–1.12) unadjusted, 3.15 (1.35-7.33) in multivariate analysis (per 1g extra scar mass) | Scar mass predicts appropriate device therapy |

| Kwon et al. 2014[125] | 450 | ≥2 SD above remote normal myocardium | 1.34 (1.15–1.55) in multivariate analysis | Scar percentage strongly predicts mortality |

| Demirel et al. 2014[126] | 99 | FWHM | 2.01 (1.17–3.44) in multivariate analysis | Ratio of peri-infarct border zone to scar core is associated with appropriate ICD therapy |

| Rijnierse et al. 2016[127] | 52 | FWHM (>50%) | Not given, p=0.07 | Trend towards higher scar burden in those with inducible VT (not significant) |

| Non-ischaemic Cardiomyopathy | ||||

| Assomull et al. 2006[62] | 101 | Visual presence of midwall LGE | 3.4 (1.4–8.7) for presence of LGE | Presence of midwall fibrosis predicts death or hospitalisation |

| Wu et al. 2008[61] | 65 | Visual presence of LGE | 8.2 (2.2–30.9) in multivariate analysis | Presence of LGE predicts cardiovascular death, ICD therapy and HF hospitalisation |

| Iles et al. 2011[128] | 61 | Visual presence of LGE | Not given, p=0.01 | Patients with LGE had significantly higher rates of appropriate ICD therapy |

| Lehrke et al. 2011[129] | 184 | Visual presence of LGE, SD >2 for quantification | 3.5 for presence of scar. 5.28 using threshold of scar >4.4% total LV mass | Presence of LGE predicts cardiac death, ICD therapy or HF hospitalisation |

| Neilan et al. 2013[130] | 162 | Both FWHM and SD methods used | 14.5 (6.1–32.6) for LGE presence, 1.15 (1.12–1.18) for each 1% increase in scar volume | Presence and volume of LGE predicts cardiovascular death or ICD therapy |

| Gulati et al. 2013[131] | 472 | Visual presence, FWHM | 2.96 (1.87–4.69) for presence of LGE, 1.1 (1.06–1.17) per 1% extra LGE | LGE presence, extent predicts mortality, independently of LVEF |

| Machii et al. 2014[132] | 72 | Visual presence of LGE | Not given, p=0.02 for extensive LGE versus no LGE | Lower event-free survival in patients with extensive LGE |

| Perazzolo-Marra et al. 2014[133] | 137 | Visual presence of LGE | 3.8 (1.3–10.4) in multivariate analysis | LGE presence, but not extent, predicts adverse arrhythmic outcome |

| Masci et al. 2014[134] | 228 | Visual presence of LGE | 4.02 (2.08–7.76) in multivariate analysis | LGE presence predicts adverse outcomes in patients with asymptomatic LVSD |

| Piers et al. 2015[68] | 87 | Visual presence, FWHM | 2.71 (1.10–6.69) for LGE presence | LGE predicts monomorphic VT, but not polymorphic VT/VF |

| Shin et al. 2016[135] | 365 | FWHM | 8.45 (2.91–24.6) for LGE extent ≥ 8%, increasing to 6.98 (1.74–28.0) for those with subepicardial pattern of disease | Presence of LGE strongly predicts arrhythmic events, risk varies with location of fibrosis |

| Mueller et al. 2016[136] | 56 | Visual presence of LGE | 1.9 (1.1–3.4) | Presence of LGE predicts VT inducibility |

| Puntmann et al. 2016[137] | 637 | T1 mapping | 1.1 (1.07–1.17) per 10 ms change in T1 time, multivariate analysis | Higher T1 values predict mortality and HF outcomes |

| Halliday et al. 2017[63] | 399 | Visual presence of LGE, FWHM for quantification | 9.2 (3.9–21.8) in patients with LVEF > 40% | A 17.8% event rate (median follow-up 4.6 years) in patients with LGE |

| Halliday et al. 2016[65] | 874 | FWHM | LGE extent of 0 to 2.55%, 2.55% to 5.10%, and >5.10%, respectively, were 1.59 (0.99 to 2.55), 1.56 (0.96 to 2.54), and 2.31 (1.50 to 3.55) for all-cause mortality | The presence and pattern, rather than the extent, of LGE predicts all-cause mortality |

| Studies Including Both ICM and NICM | ||||

| Kwong et al. 2006[138] | 195 | ≥2 SD | 8.29 (3.92–17.5) unadjusted, 8.65 (2.45–30.5) in multivariate analysis | Presence of LGE predicts cardiac events in patients with suspected CAD |

| Klem et al. 2011[51] | 1560 | Number of segments with LGE | 1.007 (1.005–1.009) unadjusted, 1.004 (1.002–1.007) in multivariate analysis | Number of segments with LGE incrementally prediction of all-cause mortality over LVSF and clinic parameters |

| Gao et al. 2012[56] | 124 | ≥2 SD | 1.4 (1.21–1.62) unadjusted | Scar quantification predicts arrhythmic events |

| Dawson et al. 2013[139] | 373 | Visual presence of LGE, FWHM for quantification | 3.5 (2.01–6.13) for presence of LGE, 1.12 per 5% extra LGE | In patients presenting with VT, LGE predicts arrhythmic events |

| Almehmadi et al. 2014[140] | 318 | ≥5 SD | 2.4 (1.2–4.6) in multivariate analysis | Midwall striation predicts sudden death or appropriate ICD therapy |

| Chen et al. 2015[70] | 130 | Native T1 value | 1.1 (1.04–1.16) per 10 ms change in T1 time, multivariate analysis | Myocardial T1 predicts ventricular arrhythmia independently of scar quantification |

| Mordi et al. 2015[141] | 539 | Visual presence of LGE | 2.14 (1.06–4.33) in multivariate analysis | LGE predicts MACE in all-comers attending for CMRI |

| Acosta et al. 2018[60] | 217 | FWHM 40–60% (border zone), >60% (scar core) | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) for border zone mass (g) | Scar mass, border zone mass and border zone channel mass all predict ICD therapy or SCD |

| Olausson et al. 2018[35] | 215 | ECV | 2.17 (1.17–4.00) for each 5% increase in ECV | Diffuse fibrosis (as evidenced by ECV) predicts appropriate ICD therapy |

Studies showing the prognostic effect of CMRI data in ischaemic cardiomyopathy and non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy. AHA = American Heart Association; CMRI = cardiac MRI; EPS = electrophysiology study; ECV = extracellular volume; FWHN = full width at half maximum; HF = heart failure; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; LV = left ventricle; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; MACE = major adverse cardiac event; VT = ventricular tachycardia.

Ischaemic Cardiomyopathy

The presence of LGE with CMRI imaging strongly predicts mortality in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy, independently of LVEF, including in patients without detectable LVSD.[50–52] Total scar burden correlates with mortality and ICD discharges, even in multivariate models including LVSD (Table 2).[51–56] Quantification of the scar border zone (rather than scar core) or quantifying the number of peri-infarct channels are alternative approaches to predicting VT/VF events.[57–60]

Non-ischaemic Cardiomyopathy

As in ICM, the presence of LGE on CMRI in patients with NICM strongly predicts mortality and arrhythmic events across the spectrum of LV impairment.[21,61–63] Patients with fibrosis identified by LGE are also less likely to achieve reverse remodelling with medical therapy.[64] The spatial distribution of fibrosis is also important, with septal scarring conferring a higher risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) than inferolateral variants, and subepicardial scarring conferring a higher risk than linear mid-wall fibrosis.[65]

Although patients with a low LVEF (<35%) have the highest individualised risk of SCD, this accounts for only ~20% of all cardiac arrests. The great majority of cardiac arrests occur outside this high-risk category.[1] Patients with fibrosis identified by LGE have worse outcomes than those without and risk stratification of individuals based on the presence or absence of LGE rather than on LVEF alone may aid patient selection for ICDs.[66] For example, compared with all those with LVEF <35% (i.e. using echocardiographic risk stratification alone), those with an LVEF >35% and LGE have similar risks of SCD.[63] Moreover, these selected patients with preservation of pump function will often have a lower competing risk of non-arrhythmic death.

In contrast with ICM, where scar-related monomorphic VT predominates, patients with NICM are more likely to experience polymorphic VT and VF.[67] On a review of the literature, most studies examining CMRI for risk stratification in NICM do not differentiate between VT and VF (Table 2). This practical approach is helpful for treatment decisions. However, Piers et al. found that scarring predicts monomorphic VT but not polymorphic VT or VF, suggesting that factors other than macroscopic anatomical substrate may be important in arrhythmogenesis in NICM.[68]

Patients with NICM with no evidence of fibrosis on CMRI have fewer arrhythmic events, a lower risk of death and a higher likelihood of reverse remodelling. Careful patient selection for prophylactic ICD implantation in this population is required, and it therefore seems logical that identification of fibrosis using CMRI could more accurately identify those who would benefit, particularly patients with NICM and those with an LVEF >35%. However, no trial data exist to supports this approach.

Late Enhancement

There is now persuasive evidence that quantification of the scar and/or border zone burden can be used to help risk stratify patients with both ICM and NICM, in addition to measures of LVEF. The fact that this relationship exists across the range of LVSD suggests that fibrosis itself is an important determinant of arrhythmic risk, rather than being simply a marker of end-stage disease.

While the presence of any degree of LGE predicts risk in both NICM and ICM, quantification of scar extent only appears to add substantial incremental risk prediction benefit in patients with ICM. However, the clinical applicability of fibrosis quantification is limited by a lack of consensus over which scar metrics and thresholds are the best predictors of outcomes, or how to apply these metrics to individuals.[69]

Extracellular Volume and T1 Mapping for Risk Stratification

Alternative metrics, such as native T1 values and ECV, measure diffuse myocardial fibrosis. In patients with both ICM and NICM, myocardial T1 values (at sites spatially discrete from areas of LGE) incrementally improved risk stratification in a model that already included LVEF, QRS duration, and metrics of scar core and border zone (using LGE).[70] In a similar study using ECV rather than T1, high ECV values correlated with mortality.[71] In two small case series, high ECV values correlated with ICD therapies.[35,72] These studies suggest that, when dense scar is surrounded by diffusely fibrotic myocardium, VT/VF is more likely than if the scar is encompassed by normal myocardium.

ECV and T1 mapping techniques have a sound physiological basis for identifying diffusely abnormal myocardium not identified with LGE imaging. ECV is of particular interest as a marker of risk in patients with NICM who do not have identifiable LGE, since it offers the ability to identify diffuse interstitial fibrosis. Complementary assessment of diffuse and regional disease by ECV mapping and LGE respectively may provide incremental benefit for risk stratification in both ICM and NICM. ECV may also have value in further characterising the density of discrete scars, although data to support this use are limited.

Ablation for Ventricular Tachycardia

For patients with a high burden of VT, catheter ablation can successfully reduce ICD shocks.[73–75] These procedures can be challenging, with significant morbidity and mortality, since VT is frequently poorly tolerated and precise localisation of re-entrant circuits using traditional electrophysiological techniques is often challenging. VT ablation therefore often targets the myocardial scar substrate.[76] Differing approaches to substrate ablation have been described – linear transection, core isolation, scar homogenisation or abolition of late potentials.[77–80] Often, this requires extensive, time-consuming ablation in haemodynamically fragile individuals, which could be streamlined with a more detailed appreciation of the underlying substrate. CMRI can be used to predict the location of re-entrant circuits and channels within the scar to guide ablation lesions, the success of which can be predicted by computer modelling.[81,82]

Planning

The configuration of LGE on CMRI allows the operator to estimate the likelihood of successful ablation and identify whether epicardial access is required. Predominantly subendocardial ischaemic scar-related VT is usually treatable with endocardial ablation.[75] Conversely, VT ablation in NICM may be hampered by inaccessibility of the substrate, and epicardial access may be required for patients with inferolateral and/or subepicardial scarring.[83] Epicardial access is typically not required for patients with VT originating from a septal intramural scar, although outcomes from ablation of ‘deep’ substrate are poorer, as might be expected.[84]

Image Fusion

Conventional 3D electroanatomical maps (EAMs) generated during ablation procedures may be inaccurate because of poor catheter contact or reach, and contact mapping of entire cardiac chambers is time consuming.

Clinical CMRI studies can be reconstructed into 3D geometries demonstrating the distribution of a scar (Figure 3). With further refinement using 3D acquisition and image-processing methods, channels that might facilitate re-entry can be identified in advance (Figure 4).[85] These geometries can be used simply as a road map for the operator during ablation procedures. Alternatively, fusion of these 3D geometries with the EAM system can leverage the accurate and high resolution anatomical detail of clinical imaging, allowing the operator to observe CMRI (and/or CT) images directly in the mapping software to reduce the time spent generating EAMs.[86–89] Contact mapping can be focused on regions of interest determined in advance, e.g. by using algorithms for localising the VT origin based on 12-lead ECG morphology or by non-invasive mapping (ECGI) techniques.[90–95] While image fusion has the potential to streamline ablation procedures, as yet, the benefits of such an approach have not been formally evaluated, and widespread applicability is not assured since it requires significant clinical and imaging expertise.

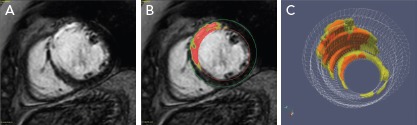

Figure 3: Image Post-processing of 2D Cardiac MRI Images.

Short axis late gadolinium enhancement images (A) are contoured to identify endo- and epicardial boundaries, before a full width at half maximum thresholding approach identifies areas of dense scar (red) and border zone (yellow), then (B) the short axis stack is reconstructed to form a 3D volume (C) which can be imported into electroanatomical maps software.

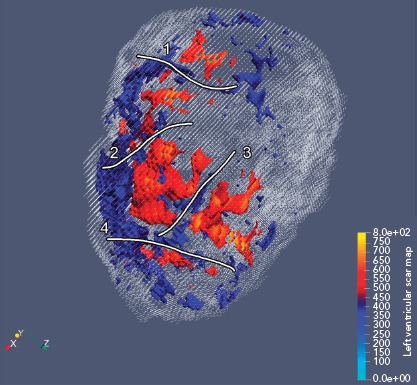

Figure 4: 3D Multiplanar Reconstruction.

Conventional clinical 2D late gadolinium enhancement imaging can pose challenges for reconstruction including slice alignment. This example of 3D multiplanar reconstruction (performed at our own institution) yields more realistic geometry with areas of dense scar (red) and border zone (blue). Putative conducting channels have been indicated and numbered in preparation for ventricular tachycardia ablation.

Future Directions

Overcoming Technical Limitations of Cardiac MRI

Many patients at risk of VT/VF have cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs).[96] Historically, MRI has been contraindicated in patients with CIEDs due to safety concerns. However, with advances in CIED technology such as MRI-conditional devices, growing experience and appropriate precautions and monitoring, CMRI can often be performed safely even in patients with historic non-conditional devices.[69,97,98] Nevertheless, images may be significantly degraded by the presence of CIEDs, particularly the anteroseptal regions of the left ventricle in patients with left-sided pulse generators that lie in close proximity to the heart. Wideband sequences are described which can reduce these artefacts.[99]

LGE imaging is usually obtained by multiple short axis planes through the heart. This results in excellent in-plane resolution, but a large slice width (approximately 10 mm) between images. Reconstructions of the heart can suffer with a ‘partial voluming’ artefact that can overestimate the infarct border zone.[100] This effect can be mitigated by evolving techniques such as 3D image acquisition or super-resolution image reconstruction.[101,102]

Histological studies have demonstrated myocyte fibre disarray at the border zone of a chronic infarction.[103] Due to anisotropic conduction of myocytes, knowledge of fibre orientation is potentially important to understand propensity to arrhythmia. Diffusion tensor imaging can demonstrate fibre direction and may therefore inform computer models of arrhythmia, although this use of CMRI is in its infancy.[12,104,105]

Ventricular Tachycardia Stimulation and Modelling

Inducibility of VT during an electrophysiology study (EPS) by programmed ventricular stimulation (PVS) pacing from a right ventricular site predicts arrhythmic events in ICM.[106] This meta-analysis demonstrated PVS had the power to predict subsequent arrhythmic events (pooled OR 4.00, 95% CI [2.30–6.96]). Depending on patient selection and the number of extrastimuli used, the sensitivity, specificity and predictive value of this test varies, although is not commonly used clinically due to its invasiveness, cost and insufficient negative predictive value. In NICM, assessment with PVS is less well studied and probably less effective than with ICM.[107]

Scar-related re-entry often relies upon functional block as well as anatomical barriers to conduction.[108] Scar quantification methods do not account for these complex mechanisms, but computer modelling has the potential to improve risk stratification by combining a personalised anatomical model with simulation of tissue electrophysiology. This method allows simulated PVS performed from multiple sites in both ventricles. In a retrospective study of 41 patients with severe LVSD, by comparing these patient-specific simulations with clinical outcomes, a positive ‘virtual-heart arrhythmia risk predictor’ simulation was associated with adverse outcomes (OR 4.05 (95% CI [1.20–13.8]), which is similar to published results from invasive PVS. Work is ongoing to determine the utility of such simulations in preserved LVSF.[82,109]

Simulated PVS methods are computationally significantly more challenging in NICM where myocardial fibrosis is less confluent and more heterogeneous, and the microscopic nature of the substrate is difficult to fully characterise with clinical imaging. Moreover, the substrate in NICM is often progressive and, as such, risk stratification at a single time point may fail to accurately estimate lifetime risk.

These methods are promising but are potentially limited by simplifications and assumptions in models of cell and tissue electrophysiology, the computational resources required, and the resolution of currently available clinical imaging. Despite encouraging preliminary studies, there are significant obstacles to be overcome before these approaches can be used routinely in clinical practice.[110] Constructing a personalised computational model of anatomy and electrophysiology requires calibration from clinical images and data that are often noisy and incomplete, so methods for embedding uncertainties and variability into computational models are an area of active research.[111] Whether these approaches can be used to guide ICD implantation in the future remains to be seen. Technological advances in imaging and modelling, along with clinical studies of their utility, will help advance this promising concept.

Future Clinical Studies

Tissue characterisation to determine who needs and, perhaps more importantly, who does not need an ICD is a complex but evolving field. Estimates of risk currently do not allow for disease progression, and it is unclear how frequently investigations should be repeated, particularly for the dynamic substrate that occurs in some forms of NICM. The effect of dynamic conditions such as electrolyte disturbance, volume overload and myocardial ischaemia on arrhythmic risk remains unknown.

In the DANish Randomized, Controlled, Multicenter Study to Assess the Efficacy of Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator in Patients With Non-ischemic Systolic Heart Failure on Mortality (DANISH) trial (NCT00542945), investigators found no overall mortality benefit for primary prevention ICD implantation in patients with NICM.[112] However, outcomes were improved by ICD implantation for those in prespecified subgroups – namely younger patients and those with lower levels of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) – who, presumably, had a lower risk of non-sudden death. Since CMRI studies have consistently demonstrated a higher arrhythmic burden in those with evidence of LGE, a clinical trial that used CMRI-based risk stratification in NICM patients with LVEF <35% would provide clinically useful information.

Similarly, the Cardiac Magnetic Resonance GUIDEd Management of Mild-moderate Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction (CMR_GUIDE) trial (NCT01918215) will identify patients who have evidence of LGE but do not qualify for ICD treatment under current guidelines (LVEF 35–50%), to determine whether prophylactic ICD implantation is beneficial.[113] The Programmed Ventricular Stimulation to Risk Stratify for Early Cardioverter-Defibrillator (ICD) Implantation to Prevent Tachyarrhythmias Following Acute Myocardial Infarction (PROTECT-ICD) trial will examine whether a multiparametric risk stratification algorithm (including echocardiography, CMRI and PVS) used post-infarction will identify those who may benefit from early ICD implantation.[114]

Contribution to Novel Therapies

Recent developments in CMRI and electrophysiology mapping systems have shown real-time tracking and visualisation of catheter position during ablation procedures to be feasible and safe for an ‘anatomical’ ablation of the cavo-tricuspid isthmus.[115,116] Advantages of such a system include 3D visualisation of catheter position within complex anatomical structures (including the ability to see surrounding structures) and real-time lesion evaluation. This technology has the potential to improve outcomes in ablation procedures, but significant technological challenges remain for its use in ventricular arrhythmia.

Stereotactic body radiotherapy has recently been reported as a novel, non-invasive treatment for VT.[117,118] It is dependent on accurate anatomical localisation of arrhythmic substrate to determine the radiotherapy target. CMRI imaging is the ideal modality for treatment planning.

Conclusion

CMRI imaging can accurately quantify cardiac function, and characterise the myocardial substrate to refine risk stratification to identify people who may benefit from ICD implantation and revascularisation. Although large-scale trials in this area are required, it is likely that measures of scar quantification will become increasingly recognised by guidelines in future.

A multiparametric approach using imaging and other criteria may provide the most accurate risk assessment in the future, although the interaction between each of the metrics discussed is complex and requires careful study. Advanced techniques such as automated image segmentation and channel detection, or computer simulation of electrophysiology, offer significant potential, but are still in the early stages of development.

Significant challenges remain in overcoming technological barriers and understanding how best to use the considerable information gained from a CMRI study. Nevertheless, CMRI offers clinicians and researchers an increasingly comprehensive way to diagnose, risk stratify and tailor the treatment of patients with cardiomyopathy.

Clinical Perspective

Cardiac MRI (CMRI) is the gold standard imaging modality for ejection fraction and myocardial tissue characterisation.

CMRI evidence of fibrosis independently predicts arrhythmic risk, even in multiparametric models which include clinical risk factors and ejection fraction, in both ischaemic and non-ischaemic cardiomyopathies.

CMRI can be used to inform and guide ablation procedures by characterising the ventricular tachycardia substrate.

Novel metrics such as extracellular volume mapping and channel identification have the potential to aid the electrophysiologist and provide a more robust method of risk stratification.

References

- 1.Huikuri HV, Castellanos A, Myerburg RJ. Sudden death due to cardiac arrhythmias. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1473–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra000650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh SN, Fletcher RD, Fisher SG et al. Amiodarone in patients with congestive heart failure and asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:77–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507133330201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bokhari F, Newman D, Greene M et al. Long-term comparison of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator versus amiodarone: eleven-year follow-up of a subset of patients in the Canadian Implantable Defibrillator Study (CIDS) Circulation. 2004;110:112–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000134957.51747.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:877–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB et al. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2793–867. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellenger NG, Davies LC, Francis JM et al. Reduction in sample size for studies of remodeling in heart failure by the use of cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2000;2:271–8. doi: 10.3109/10976640009148691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Josephson ME. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology: Techniques and Interpretations. 4th ed. [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Bakker JM, van Capelle FJ, Janse MJ et al. Slow conduction in the infarcted human heart. ‘Zigzag’ course of activation. Circulation. 1993;88:915–26. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.88.3.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estner HL, Zviman MM, Herzka D et al. The critical isthmus sites of ischemic ventricular tachycardia are in zones of tissue heterogeneity, visualized by magnetic resonance imaging. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1942–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenoglio JJ, Pham TD, Harken AH et al. Recurrent sustained ventricular tachycardia: structure and ultrastructure of subendocardial regions in which tachycardia originates. Circulation. 1983;68:518–33. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.68.3.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pashakhanloo F, Herzka DA, Halperin H et al. Role of 3-dimensional architecture of scar and surviving tissue in ventricular tachycardia: insights from high-resolution ex vivo porcine models. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018;11:e006131. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.117.006131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nalliah CJ, Zaman S, Narayan A et al. Coronary artery reperfusion for ST elevation myocardial infarction is associated with shorter cycle length ventricular tachycardia and fewer spontaneous arrhythmias. Europace. 2014;16:1053–60. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piers SRD, Wijnmaalen A, Borleffs C et al. Early reperfusion therapy affects inducibility, cycle length, and occurrence of ventricular tachycardia late after myocardial infarction. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:195–201. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.959213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wijnmaalen A, Schalij MJ, von der Thüsen JH et al. Early reperfusion during acute myocardial infarction affects ventricular tachycardia characteristics and the chronic electroanatomic and histological substrate. Circulation. 2010;121:1887–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.891242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinov B, Fiedler L. Schönbauer R, et al. Outcomes in catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in dilated nonischemic cardiomyopathy compared with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2014;129:728–36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glashan CA, Androulakis AFA, Tao Q et al. Whole human heart histology to validate electroanatomical voltage mapping in patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy and ventricular tachycardia. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2867–75. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu TJ, Ong JJ, Hwang C et al. Characteristics of wave fronts during ventricular fibrillation in human hearts with dilated cardiomyopathy: role of increased fibrosis in the generation of reentry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:187–96. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(98)00184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nash MP, Mourad A, Clayton RH et al. Evidence for multiple mechanisms in human ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 2006;114:536–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.602870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Parrish TB et al. Relationship of MRI delayed contrast enhancement to irreversible injury, infarct age, and contractile function. Circulation. 1999;100:1992–2002. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.19.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venero JV, Doyle M, Shah M et al. Mid wall fibrosis on CMR with late gadolinium enhancement may predict prognosis for LVAD and transplantation risk in patients with newly diagnosed dilated cardiomyopathy-preliminary observations from a high-volume transplant centre. ESC Heart Fail. 2015;2:150–9. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu L-Y, Natanzon A, Kellman P et al. Quantitative myocardial infarction on delayed enhancement MRI. Part I: animal validation of an automated feature analysis and combined thresholding infarct sizing algorithm. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;23:298–308. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan JN, Nazir SA, Horsfield MA Comparison of semi-automated methods to quantify infarct size and area at risk by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging at 1.5T and 3.0T field strengths. BMC Res Notes. 2015. p. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Amado LC, Gerber BL, Gupta SN et al. Accurate and objective infarct sizing by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in a canine myocardial infarction model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2383–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jablonowski R, Chaudhry U, van der Pals J Cardiovascular magnetic resonance to predict appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy patients using late gadolinium enhancement border zone: comparison of four analysis methods. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017. p. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Flett AS, Hasleton J, Cook C et al. Evaluation of techniques for the quantification of myocardial scar of differing etiology using cardiac magnetic resonance. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:150–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kellman P, Arai AE, Xue H. T1 and extracellular volume mapping in the heart: estimation of error maps and the influence of noise on precision. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:56. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haaf P, Garg P, Messroghli DR et al. Cardiac T1 mapping and extracellular volume (ECV) in clinical practice: a comprehensive review. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18:89. doi: 10.1186/s12968-016-0308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schelbert EB, Messroghli DR. State of the art: clinical applications of cardiac T1 mapping. Radiology. 2016;278:658–76. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016141802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Germain P, El Ghannudi S, Jeung M-Y et al. Native T1 mapping of the heart – a pictorial review. Clin Med Insights Cardiol. 2014;8:1–11. doi: 10.4137/CMC.S19005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dabir D, Child N, Kalra A et al. Reference values for healthy human myocardium using a T1 mapping methodology: results from the International T1 Multicenter cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2014;16:69. doi: 10.1186/s12968-014-0069-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sado DM, Flett AS, Banypersad SM et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance measurement of myocardial extracellular volume in health and disease. Heart. 2012;98:1436–41. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sibley CT, Noureldin RA, Gai N et al. T1 mapping in cardiomyopathy at cardiac MR: comparison with endomyocardial biopsy. Radiology. 2012;265:724–32. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salerno M, Kramer CM. Advances in parametric mapping with CMR imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:806–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olausson E, Fröjdh F, Maanja M et al. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis measured by extracellular volume associates with incident ventricular arrhythmia in implantable cardioverter defibrillator recipients more than focal fibrosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(suppl 11):A1454. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(18)31995-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tada Y, Yang PC. Myocardial edema on T2-weighted MRI. Circ Res. 2017;121:326–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lota AS, Gatehouse PD, Mohiaddin RH. T2 mapping and T2* imaging in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2017;22:431–40. doi: 10.1007/s10741-017-9616-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mavrogeni S, Apostolou D, Argyriou P et al. T1 and T2 mapping in cardiology: ‘mapping the obscure object of desire’. Cardiology. 2017;138:207–17. doi: 10.1159/000478901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129–200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:e91–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White JA, Fine NM, Gula L et al. Utility of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in identifying substrate for malignant ventricular arrhythmias. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:12–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.966085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piers SRD, Tao Q, van Huls van Taxis CF et al. Contrast-enhanced MRI-derived scar patterns and associated ventricular tachycardias in nonischemic cardiomyopathy: implications for the ablation strategy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:875–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braunwald E, Rutherford JD. Reversible ischemic left ventricular dysfunction: Evidence for the ‘hibernating myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1467–70. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(86)80325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brugada J, Aguinaga L, Mont L et al. Coronary artery revascularization in patients with sustained ventricular arrhythmias in the chronic phase of a myocardial infarction: effects on the electrophysiologic substrate and outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:529–33. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)01133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ngaage DL, Cale ARJ, Cowen ME et al. Early and late survival after surgical revascularization for ischemic ventricular fibrillation/tachycardia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:1278–81. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly P, Ruskin JN, Vlahakes GJ et al. Surgical coronary revascularization in survivors of prehospital cardiac arrest: Its effect on inducible ventricular arrhythmias and long-term survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:267–73. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(10)80046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Geelen P, Primo J, Wellens F, Brugada P. Coronary artery bypass grafting and defibrillator implantation in patients with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and ischemic heart disease. Pacing Clin Electrophysioly. 1999;22:1132–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1999.tb00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dumas F, Bougouin W, Geri G et al. Emergency percutaneous coronary intervention in post-cardiac arrest patients without st-segment elevation pattern: insights from the PROCAT II Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:1011–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cook JR, Rizo-Patron C, Curtis AB et al. Effect of surgical revascularization in patients with coronary artery disease and ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation in the Antiarrhythmics Versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) Registry. Am Heart J. 2002;143:821–6. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.121732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwon DH, Halley CM, Carrigan TP et al. Extent of left ventricular scar predicts outcomes in ischemic cardiomyopathy patients with significantly reduced systolic function: a delayed hyperenhancement cardiac magnetic resonance study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klem I, Shah DJ, White RD et al. Prognostic value of routine cardiac magnetic resonance assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction and myocardial damage: an international, multicenter study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:610–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.964965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheong BYC, Muthupillai R, Wilson JM et al. Prognostic significance of delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging: survival of 857 patients with and without left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2009;120:2069–76. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.852517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scott PA, Morgan JM, Carroll N et al. The extent of left ventricular scar quantified by late gadolinium enhancement MRI is associated with spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias in patients with coronary artery disease and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:324–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.959544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bello D, Fieno DS, Kim RJ et al. Infarct morphology identifies patients with substrate for sustained ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1104–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Disertori M, Rigoni M, Pace N et al. Myocardial fibrosis assessment by LGE is a powerful predictor of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in ischemic and nonischemic LV dysfunction: a meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:1046–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao P, Yee R, Gula L et al. Prediction of arrhythmic events in ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathy patients referred for implantable cardiac defibrillator: evaluation of multiple scar quantification measures for late gadolinium enhancement magnetic resonance imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:448–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.971549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heidary S, Patel H, Chung J et al. Quantitative tissue characterization of infarct core and border zone in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy by magnetic resonance is associated with future cardiovascular events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2762–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yan AT, Shayne AJ, Brown KA et al. Characterization of the peri-infarct zone by contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is a powerful predictor of post-myocardial infarction mortality. Circulation. 2006;114:32–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.613414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rubenstein JC, Lee DC, Wu E et al. A comparison of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging peri-infarct border zone quantification strategies for the prediction of ventricular tachyarrhythmia inducibility. Cardiol J. 2013;20:68–77. doi: 10.5603/CJ.2013.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Acosta J. Fernández-Armenta J, Borràs R, et al. Scar characterization to predict life-threatening arrhythmic events and sudden cardiac death in patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:561–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu KC, Weiss RG, Thiemann DR et al. Late gadolinium enhancement by cardiovascular magnetic resonance heralds an adverse prognosis in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2414–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Assomull RG, Prasad SK, Lyne J et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance, fibrosis, and prognosis in dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1977–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Halliday BP, Gulati A, Ali A et al. Association between midwall late gadolinium enhancement and sudden cardiac death in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and mild and moderate left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Circulation. 2017;135:2106–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Becker MAJ, Cornel JH. van de Ven PM, et al. The prognostic value of late gadolinium-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: a review and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:1274–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Halliday BP, Baksi AJ, Gulati A Outcome in dilated cardiomyopathy related to the extent, location, and pattern of late gadolinium enhancement. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018. epub ahead of press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Kuruvilla S, Adenaw N, Katwal AB et al. Late gadolinium enhancement on CMR predicts adverse cardiovascular outcomes in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:250–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.001144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ermis C, Zhu AX, Vanheel L et al. Comparison of ventricular arrhythmia frequency in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy versus nonischemic cardiomyopathy treated with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:233–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Piers SRD, Everaerts K, van der Geest RJ et al. Myocardial scar predicts monomorphic ventricular tachycardia but not polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:2106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Messroghli DR, Moon JC, Ferreira VM et al. Clinical recommendations for cardiovascular magnetic resonance mapping of T1, T2, T2* and extracellular volume: a consensus statement by the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) endorsed by the European Association for Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2017;19:75. doi: 10.1186/s12968-017-0389-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen Z, Sohal M, Voigt T et al. Myocardial tissue characterization by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging using T1 mapping predicts ventricular arrhythmia in ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:792–801. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wong TC, Piehler K, Meier CG et al. Association between extracellular matrix expansion quantified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance and short-term mortality. Circulation. 2012;126:1206–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.089409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barison A, Torto AD, Chiappino S Prognostic significance of myocardial extracellular volume fraction in nonischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Med. 2015. p. 16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Kuck K-H, Schaumann A, Eckardt L et al. Catheter ablation of stable ventricular tachycardia before defibrillator implantation in patients with coronary heart disease (VTACH): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:31–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61755-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sapp JL, Wells GA, Parkash R et al. Ventricular tachycardia ablation versus escalation of antiarrhythmic drugs. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:111–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marchlinski FE, Haffajee CI, Beshai JF et al. Long-term success of irrigated radiofrequency catheter ablation of sustained ventricular tachycardia: post-approval THERMOCOOL VT Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:674–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reddy VY, Reynolds MR, Neuzil P et al. Prophylactic catheter ablation for the prevention of defibrillator therapy. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2657–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Marchlinski FE, Callans DJ, Gottlieb CD, Zado E. Linear ablation lesions for control of unmappable ventricular tachycardia in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2000;101:1288–96. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.11.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tzou WS, Frankel DS, Hegeman T et al. Core isolation of critical arrhythmia elements for treatment of multiple scar-based ventricular tachycardias. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:353–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gökoğlan Y, Mohanty S, Gianni C et al. Scar homogenization versus limited-substrate ablation in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy and ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1990–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jaïs P, Maury P, Khairy P et al. Elimination of local abnormal ventricular activities: a new end point for substrate modification in patients with scar-related ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2012;125:2184–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.043216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Andreu D, Berruezo A, Ortiz-Pérez JT et al. Integration of 3D electroanatomic maps and magnetic resonance scar characterization into the navigation system to guide ventricular tachycardia ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:674–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.961946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Arevalo HJ, Vadakkumpadan F, Guallar E et al. Arrhythmia risk stratification of patients after myocardial infarction using personalized heart models. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11437. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cano O, Hutchinson M, Lin D et al. Electroanatomic substrate and ablation outcome for suspected epicardial ventricular tachycardia in left ventricular nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:799–808. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Oloriz T, Silberbauer J, Maccabelli G et al. Catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmia in nonischemic cardiomyopathy: anteroseptal versus inferolateral scar sub-types. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7:414–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Andreu D, Penela D, Acosta J et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance-aided scar dechanneling: Influence on acute and long-term outcomes. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:1121–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Njeim M, Desjardins B, Bogun F. Multimodality imaging for guiding EP ablation procedures. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:873–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yamashita S, Sacher F, Mahida S et al. Image integration to guide catheter ablation in scar-related ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27:699–708. doi: 10.1111/jce.12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kelland NF, Metherall P, Sugden J et al. Multimodality image reconstruction and fusion to guide VT ablation. Europace. 2017;19 (suppl 1):i–17. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux283.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wijnmaalen AP, van der Geest RJ, van Huls van Taxis CFB et al. Head-to-head comparison of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and electroanatomical voltage mapping to assess post-infarct scar characteristics in patients with ventricular tachycardias: real-time image integration and reversed registration. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:104–14. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sapp JL, Bar-Tal M, Howes AJ et al. Real-time localization of ventricular tachycardia origin from the 12-lead electrocardiogram. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2017;3:687–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2017.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Andreu D, Fernández-Armenta J, Acosta J et al. A QRS axis-based algorithm to identify the origin of scar-related ventricular tachycardia in the 17-segment American Heart Association model. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:1491–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Segal OR, Chow AWC, Wong T et al. A novel algorithm for determining endocardial VT exit site from 12-lead surface ECG characteristics in human, infarct-related ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:161–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Miller JM, Marchlinski FE, Buxton AE, Josephson ME. Relationship between the 12-lead electrocardiogram during ventricular tachycardia and endocardial site of origin in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1988;77:759–66. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.77.4.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kuchar DL, Ruskin JN, Garan H. Electrocardiographic localization of the site of origin of ventricular tachycardia in patients with prior myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:893–903. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang Y, Cuculich PS, Zhang J et al. Noninvasive electroanatomic mapping of human ventricular arrhythmias with electrocardiographic imaging. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:98–ra84. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kalin R, Stanton MS. Current clinical issues for MRI scanning of pacemaker and defibrillator patients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28:326–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.50024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nazarian S, Hansford R, Roguin A et al. A prospective evaluation of a protocol for magnetic resonance imaging of patients with implanted cardiac devices. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:415–24. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-7-201110040-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Russo RJ, Costa HS, Silva PD et al. Assessing the risks associated with MRI in patients with a pacemaker or defibrillator. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:755–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Do DH, Eyvazian V, Bayoneta AJ et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging using wideband sequences in patients with nonconditional cardiac implanted electronic devices. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:218–25. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schelbert EB, Hsu L-Y, Anderson SA et al. Late gadolinium-enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance identifies postinfarction myocardial fibrosis and the border zone at the near cellular level in ex vivo rat heart. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:743–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.835793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Amano Y, Yanagisawa F, Tachi M et al. Three-dimensional cardiac MR imaging: related techniques and clinical applications. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2017;16:183–9. doi: 10.2463/mrms.rev.2016-0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dzyubachyk O, Tao Q, Poot DHJ et al. Super-resolution reconstruction of late gadolinium-enhanced MRI for improved myocardial scar assessment. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42:160–7. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hervas A, Ruiz-Sauri A, de Dios E et al. Inhomogeneity of collagen organization within the fibrotic scar after myocardial infarction: results in a swine model and in human samples. J Anat. 2016;228:47–58. doi: 10.1111/joa.12395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.León DG, López-Yunta M, Alfonso-Almazán JM Three-dimensional cardiac fibre disorganization as a novel parameter for ventricular arrhythmia stratification after myocardial infarction. Europace. 2019. epub ahead of press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 105.Mekkaoui C, Reese TG, Jackowski MP et al. Diffusion MRI in the heart. NMR Biomed. 2017;30:3. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Disertori M. Masè M, Rigoni M, et al. Ventricular tachycardia-inducibility predicts arrhythmic events in post-myocardial infarction patients with low ejection fraction. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2018;20:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Plummer C. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy for non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy. What is the role of programmed electrical stimulation? Europace. 2009;11:273–5. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Segal OR, Chow AWC, Peters NS et al. Mechanisms that initiate ventricular tachycardia in the infarcted human heart. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Deng D, Arevalo HJ, Prakosa A et al. A feasibility study of arrhythmia risk prediction in patients with myocardial infarction and preserved ejection fraction. Europace. 2016;18:iv60–6. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Prakosa A, Arevalo HJ, Deng D et al. Personalized virtual-heart technology for guiding the ablation of infarct-related ventricular tachycardia. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2:732–40. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0282-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mirams GR, Pathmanathan P, Gray RA et al. Uncertainty and variability in computational and mathematical models of cardiac physiology. J Physiol. 2016;594:6833–47. doi: 10.1113/JP271671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Køber L, Thune JJ, Nielsen JC et al. Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1221–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Selvanayagam JB, Hartshorne T, Billot L Cardiovascular magnetic resonance-GUIDEd management of mild to moderate left ventricular systolic dysfunction (CMR GUIDE): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2017. p. 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 114.Zaman S, Taylor AJ, Stiles M et al. Programmed Ventricular Stimulation to Risk Stratify for Early Cardioverter-Defibrillator Implantation to Prevent Tachyarrhythmias following Acute Myocardial Infarction (PROTECT-ICD): trial protocol, background and significance. Heart Lung Circ. 2016;25:1055–62. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chubb H, Williams SE, Whitaker J et al. Cardiac electrophysiology under MRI guidance: an emerging technology. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2017;6:85–93. doi: 10.15420/aer.2017.1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hilbert S, Sommer P, Gutberlet M et al. Real-time magnetic resonance-guided ablation of typical right atrial flutter using a combination of active catheter tracking and passive catheter visualization in man: initial results from a consecutive patient series. Europace. 2016;18:572–7. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cuculich PS, Schill MR, Kashani R et al. Noninvasive cardiac radiation for ablation of ventricular tachycardia. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2325–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Robinson CG, Samson PP, Moore KM et al. Phase I/II trial of electrophysiology-guided noninvasive cardiac radioablation for ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2019;139:313–321. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schmidt A, Azevedo CF, Cheng A et al. Infarct tissue heterogeneity by magnetic resonance imaging identifies enhanced cardiac arrhythmia susceptibility in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2007;115:2006–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Roes SD, Borleffs CJW, van der Geest RJ et al. Infarct tissue heterogeneity assessed with contrast-enhanced MRI predicts spontaneous ventricular arrhythmia in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:183–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.826529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kelle S, Roes SD, Klein C et al. Prognostic value of myocardial infarct size and contractile reserve using magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1770–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Krittayaphong R, Saiviroonporn P, Boonyasirinant T et al. Prevalence and prognosis of myocardial scar in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease and normal wall motion. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13:2. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-13-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Boyé P, Abdel-Aty H, Zacharzowsky U et al. Prediction of life-threatening arrhythmic events in patients with chronic myocardial infarction by contrast-enhanced CMR. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:871–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Alexandre J, Saloux E, Dugué AE et al. Scar extent evaluated by late gadolinium enhancement CMR: a powerful predictor of long term appropriate ICD therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:12. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kwon DH, Hachamovitch R, Adeniyi A et al. Myocardial scar burden predicts survival benefit with implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation in patients with severe ischaemic cardiomyopathy: influence of gender. Heart. 2014;100:206–13. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Demirel F, Adiyaman A, Timmer JR et al. Myocardial scar characteristics based on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is associated with ventricular tachyarrhythmia in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:392–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rijnierse MT, Allaart CP. Haan S de, et al. Non-invasive imaging to identify susceptibility for ventricular arrhythmias in ischaemic left ventricular dysfunction. Heart. 2016;102:832–40. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]